Erectile dysfunction in men may be due to multiple causes, including anxiety and substance abuse. The main objective of this study is to know how it affects the continued use of addictive substances in the erectile response, taking into account not only the type of substances consumed, but also other variables that may influence on sexual response, such as the time of withdrawal, anxiety and sexual attitude. Two samples were used, one for males (n=925) who had a history of substance use and another one for males (n=82) with no history of substance abuse. Both populations were selected by a cluster sampling of 27 Spanish provinces. The GRISS, SOS and STAI questionnaires were used. The results indicate that men with a history of consumption obtained a higher percentage of dysfunction in the erectile dysfunction questionnaire GRISS scale than those who have a history of consumption (36.69% vs.15.85%) who also have higher scores on state anxiety (19.83 vs.11.89) and trait anxiety (25.66 vs.12.39) and lowest in erotophilia (86.85 vs. 97.29) was statistically significant difference. It is also proved that the time of withdrawal does not help ex drug users improve their erectile response.

La disfunción eréctil en el hombre puede deberse a múltiples causas, entre ellas la ansiedad y el consumo de sustancias adictivas. El objetivo del presente estudio fue conocer cómo afecta el consumo continuado de sustancias adictivas a la respuesta eréctil, teniendo en cuenta además del tipo de sustancias consumidas, otras variables que pueden influir en la respuesta sexual, como el tiempo de abstinencia, la ansiedad y las actitudes sexuales. La muestra constaba de dos grupos, uno de hombres (n=925) con un historial de consumo de sustancias y otro (n=82) sin historial de consumo de sustancias adictivas. Ambas muestras fueron seleccionadas, mediante muestreo por conglomerados, en 27 provincias españolas. Se utilizaron los cuestionarios GRISS, STAI y SOS. Los hombres con historial de consumo obtuvieron un mayor porcentaje de disfuncionalidad en la escala disfunción eréctil del GRISS que aquellos que no tenían una historia de consumo (36,69% vs. 15,85%), además mostraron puntuaciones mayores en ansiedad estado (19,83 vs.11,89) y ansiedad rasgo (25,66 vs. 2,39) y menores en erotofilia (86,85 vs. 97,29), siendo la diferencia estadísticamente significativa. Asimismo, se descarta que el tiempo de abstinencia ayude a mejorar la respuesta eréctil de los hombres exconsumidores de drogas.

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is the inability to achieve or maintain an erection with the rigidity required to complete satisfactory sexual relations (National Institute of Health Consensus Development Panel on Impotence, NIHCDPI, 1993). ICD-10 (Organización Mundial de la Salud, OMS, 1992) defines it as difficulty to achieve or maintain an adequate erection for satisfactory penetration, including psychogenic impotence and erectile disorders. In the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, APA, 2013) ED is defined as a partial or complete, reoccurring or persistent failure to obtain or maintain an erection through the end of sexual activity.

Years ago ED was considered to be of psychological origin in 75-95% of cases (Abraham & Porto, 1979). However, the emergence of new diagnostic methods revealed organic causes in a majority of them. For this reason, ED was etiologically classified as organic, psychogenic or mixed. Therefore, some authors establish that ED with psychogenic origin is 10% of the total (Stief, Bahren, Scherb, & Gall, 1989). Hanash (1997) found that 20-30% of erectile dysfunctions were purely psychogenic and that mixed cause could reach 66%, while other authors report 37% for organic, 33% for mixed and 30% for purely psychogenic (Farré & Lasheras, 1998). In any case it is necessary to bear in mind that in all cases of ED there is a psychological component, independent of if a possible original organic cause exists.

From a clinical point of view, the most relevant is to determine the predisposing, precipitant and maintaining factors for the dysfunction. In any of the three groups, anxiety and attitudes towards sexuality play fundamental roles. An important, and not very studied, etiological agent that causes ED is substance use. Although, some studies have suggested that substance use may improve sexual functioning in a fleeting way in the short term (Degenhardt & Topp, 2003). It has long term effects on sexual response (Johnson, Phelps, & Cottler, 2004). Thus, people who have used addictive substances have on average a higher number of sexual dysfunctions that people who have not (Blanco, Pérez, & Batista, 2011; Duany, 2013; Groves, Sarkar, Nebhinan, Mattoo, & Basu, 2014; Grover, Shah, Dutt, & Avasthi, 2012; Hernández, 2012; Lèvy & Garnier, 2006; McKay, 2005; Smith, 2007), ED being one of them (Cabello, 2010; Cabello, Díaz, & Del Río, 2013; Díaz, Del Río & Cabello, 2013; Fora, 2013; Jiann, 2009; Labairu, Padilla, Arrondo, & Lorenzo, 2013; Segraves & Balon, 2014; Vallejo-Medina, Guillén-Riquelme, & Sierra, 2009).

The principal objective of this study was to understand how substance use affects erectile response in men with a history of previous addictive substance use, taking into account, in addition to the substances used, other variables that may influence sexual response, such as anxiety and attitudes towards sexuality. The following hypothesis were formed: 1) men who have used addictive substances will present a higher incidence of erectile dysfunction than those who have not used them; 2) the longer the abstinence periods, the better the erectile response will be; 3) men who are substance users will, on average, present more erotophobic attitudes than men who were not consumers; 4) men who are substance users will present higher anxiety than men who have not been consumers; 5) the type of commonly consumed substance (stimulant, depressant or psychedelic) will influence the erectile response differently; and 6) older men will present more difficulties in the erectile response.

MethodParticipantsTwo samples, one corresponding to males with a history of substance abuse (n = 925) and another formed by men with no history of substance abuse (n = 82) were used. Both samples were selected by cluster sampling in 27 Spanish provinces. Substance users showed an age range between 18 and 61 years (M = 34.56, SD = 7.67), 454 (49.08%) had a partner, with an average of 8.41 years of cohabitation, and 471 (50.92%) did not. Non-users had an age range between 19 and 61 years (M = 36.30, SD = 8.30), 69 (84.15%) had a partner, with a mean of 10.90 years of cohabitation, and 13 (15.85%) were not in a relationship.

For inclusion in the study, participants had to be of legal age, have or have had a sexual partner for more than six months time and voluntarily accept study participation. People who had any mental disease cataloged in the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, APA, 2002), except for substance addiction, impulse control deficits and sexual dysfunction, as well as the people taking any medication were excluded from the study.

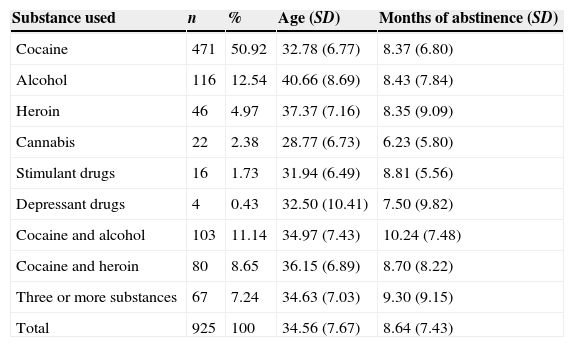

The sociodemographic data for the substance user group included the type of substance habitually used before detoxification. Data are presented in Table 1.

Type of substance consumed by the substance user group men.

| Substance used | n | % | Age (SD) | Months of abstinence (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cocaine | 471 | 50.92 | 32.78 (6.77) | 8.37 (6.80) |

| Alcohol | 116 | 12.54 | 40.66 (8.69) | 8.43 (7.84) |

| Heroin | 46 | 4.97 | 37.37 (7.16) | 8.35 (9.09) |

| Cannabis | 22 | 2.38 | 28.77 (6.73) | 6.23 (5.80) |

| Stimulant drugs | 16 | 1.73 | 31.94 (6.49) | 8.81 (5.56) |

| Depressant drugs | 4 | 0.43 | 32.50 (10.41) | 7.50 (9.82) |

| Cocaine and alcohol | 103 | 11.14 | 34.97 (7.43) | 10.24 (7.48) |

| Cocaine and heroin | 80 | 8.65 | 36.15 (6.89) | 8.70 (8.22) |

| Three or more substances | 67 | 7.24 | 34.63 (7.03) | 9.30 (9.15) |

| Total | 925 | 100 | 34.56 (7.67) | 8.64 (7.43) |

The validated Spanish version by Aluja and Farré (cited by Blázquez et al., 2008) of the Golombok Rust Inventory of Sexual Satisfaction (GRISS; Rust & Golombok, 1986) was used. It assesses sexual function of heterosexual couples who have an active sexuality. There is one version for men and one for women, each with 28 items, which are answered on a Likert scale of 5 points (from Never to Always). Nine different sub-scales are included: Infrequency, No communication, Dissatisfaction, Non-sensuality, Avoidance, Impotence (Erectile Dysfunction), Premature Ejaculation, Anorgasmia and Vaginismus. This study only analyzed data from the Erectile Dysfunction scale. Cronbach's alpha of the questionnaire for each of the two groups was calculated, resulting in a score of .73 for the substance user group and .74 for non-users.

Sexual Opinion Survey (SOS; Fisher, Byrne, White, & Kelley, 1988) was employed to assess the erotophobia-erotophilia. These constructs as defined by Fisher et al. (1988) are a learned disposition to respond to sexual stimuli along a continuum that extends from negative (erotophobia) to positive (erotophilia). Thus, people who score high on erotophobia tend to have more negative attitudes to sexual stimuli, and those who score highly in erotophilia will show more positive attitudes to sexual stimuli. The Spanish validation by Carpintero and Fuertes (1994) consists of 21 items answered on a Likert scale with 7 response options (1 = strongly agree; 7 = strongly disagree) was used. The authors reported a Cronbach's alpha of .86. In this study, a coefficient of .75 was obtained in the consumer group and .87 in the control.

State-Trait Anxiety Questionnaire (STAI; Spielberger, Gorsuch, & Lushene, 1982) is designed to measure anxiety. It has two self-rating scales to measure two independent concepts of anxiety: state and trait. Both scales have 20 items rated on a Likert scale of 0-3 points. The Spanish adaptation has good internal consistency between .90 and .93 for anxiety/state and between .84 and .87 for anxiety/trait. In this study was obtained from the anxiety scale a value of .89 in the substance user group and .90 in the non-user group, and the trait anxiety scale, .88 to .84 for users and non-users.

ProcedureNon-probability sampling by conglomerates was performed, consisting of selecting treatment centers for drug addicts distributed throughout the country and asking them to participate in the study. To ensure that the sample was sufficiently large, provinces from all of the Autonomous Communities (at least one province in each) were selected. Participants were divided into two groups: the substance users group of people who were undergoing treatment for drug addiction and group of non-users of people who belonged to the same cluster; they were workers or treatment center workers. Once the questionnaires were answered, different treatment centers forwarded to the study authors for correction and subsequent statistical analysis.

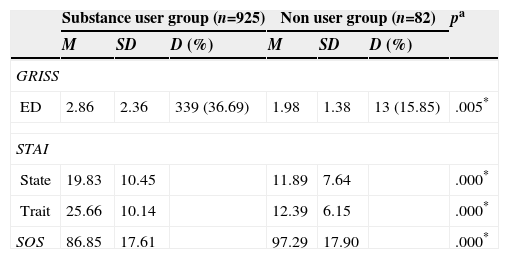

ResultsIn Table 2, the descriptive data for the two samples are presented. It is observed that the substance user group obtained higher scores on the Erectile Dysfunction GRISS scale, these scores indicate greater severity. When the raw score is transformed, using the criteria of the authors of the questionnaire (Rust & Golombok, 1986) it shows that the percentage of dysfunctional participants is higher in the group of male consumers of substances. Furthermore, those in the substance user group obtained higher anxiety scores: both state anxiety and trait anxiety, and lower scores on the SOS. These results indicate that male substance users are more erotophobic than nonusers.

Descriptive data and differences between groups.

| Substance user group (n=925) | Non user group (n=82) | pa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | D (%) | M | SD | D (%) | ||

| GRISS | |||||||

| ED | 2.86 | 2.36 | 339 (36.69) | 1.98 | 1.38 | 13 (15.85) | .005* |

| STAI | |||||||

| State | 19.83 | 10.45 | 11.89 | 7.64 | .000* | ||

| Trait | 25.66 | 10.14 | 12.39 | 6.15 | .000* | ||

| SOS | 86.85 | 17.61 | 97.29 | 17.90 | .000* | ||

Note: ED = Erectile Dysfunction; D =people who obtained dysfunctional scores on the GRISS aMann-Whitney U test *p < .01.

The mean abstinence time of consumers was 8.66 months, with a standard deviation of 8.25. The minimum time was one month and maximum two years. The mode was 1 month. To check if withdrawal time is related to the presence of ED, the substance user group was split into three groups depending on withdrawal time at the moment of evaluation: 1 to 4 months, 5 to 12 months and over 12 months without substance use. The average score on the ED scale decreased as abstinence time increased. To check whether there were statistically significant differences in scores based on the time of withdrawal the Kruskal-Wallis test was performed. The result indicates that the differences are not statistically significant (χ2(2) = 2.30, p = .316). In addition, a bivariate correlation analysis was performed, analyzing the relationship between the withdrawal time variable and ED scale scores. Because the data did not meet the requirements for the use of parametric tests, Spearman Rho correlation was carried out. The results indicate no significant correlation between the time of withdrawal and the score on the scale of (Rho = -.04, p = .155).

To analyze the relationship between ED and the type of addictive substance consumed, a Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess whether there were statistically significant differences between the different substances. The result indicated that there were no significant differences (p = .095) between the different drugs taken separately. For this reason it was decided to group people according to the type of substance. Were divided participants into groups by the effects of the substances on the central nervous system: stimulant, depressant or psychedelic. The classification was carried out as follows, people who had used cocaine or stimulant psychotropic drugs were included in the group of stimulants, persons who had used heroin, alcohol or psychotropic depressants were included in the group of depressants and finally those who had used cannabis were included in the group of psychedelic substances. Participants who had used mixtures of substances that did not pertain to the same group (cocaine and alcohol, cocaine and heroin, or three or more substances) and nonusers were left out of the analysis. Mean scores on the scale of Erectile Dysfunction depending on the substance used were: stimulants (M = 2.73, SD = 2.39), depressants (M = 3.25, SD = 2.41) and psychedelic (M = 3.27, SD = 2.31). The results of the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test are statistically significant (χ2(2) = 7.85, p = .020). Dunn's test showed that statistically significant differences were found between stimulants and depressants, indicating that people who have used depressants are more likely to have ED than those who consumed stimulants.

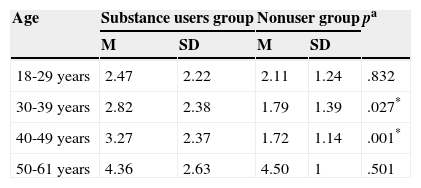

To test whether age negatively influences erectile response, the relationship between age and response to the scale of erectile dysfunction was analyzed using Spearman's Rho test. A significant result was yielded, thus taking all the data together (Rho = .14, p = .000), how the data using only consumer group (Rho = .15, p = .000). When the two groups are compared taking into account the age variable, it is observed that the differences are between 30-39 and 40-49 years of age (Table 3).

Erectile dysfunction scale scores by group between substance users and nonusers, considering the variable of age.

| Age | Substance users group | Nonuser group | pa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| 18-29 years | 2.47 | 2.22 | 2.11 | 1.24 | .832 |

| 30-39 years | 2.82 | 2.38 | 1.79 | 1.39 | .027* |

| 40-49 years | 3.27 | 2.37 | 1.72 | 1.14 | .001* |

| 50-61 years | 4.36 | 2.63 | 4.50 | 1 | .501 |

Note: aMann-Whitney U test; *p < .01.

The main focus of this study was to analyze the difficulties in erectile response that may occur in men who have been regular users of addictive substances. In view of the results obtained, it can be concluded that people who have had experiences of consumption have more erectile difficulties than nonusers. Several studies found similar results. Vallejo-Medina et al. (2009) reported that the erection scale scores obtained by people with a history of substance abuse were lower than those of non-users. Jiann (2009) indicated that, in a study of 701 men in drug treatment centers in Taiwan, 36.4% had ED; 10.4% of which being severe cases. Jiann (2009) concluded that both snuff and alcohol and illegal drugs have adverse effects on erectile function. Therefore, the results obtained in this study are consistent with the few studies on ED in drug users.

As for abstinence, if the substance can cause ED in men, cessation of use should cause said dysfunction to disappear and improve sexual response over time. However, the results obtained indicate that abstinence does not improve erectile response in men who have been substance users. In the literature, we find similar results, indicating that sexual response does not improve with the cessation of substance use (Del Río, Fernandez, & Cabello, 2013). Vallejo-Medina and Sierra (2013) found that substance users did not significantly improve in the sexual area after a year of abstinence. Jiann (2008) obtained similar results, claiming that the neurological damage caused by addictive substances are long lasting. This is a very important aspect to consider therapeutically with people consuming of addictive substances, as against common sense, abstinence does not improve sexual response. Therefore, work of a specific depth regarding sexual dysfunction in drug treatment centers is necessary. One that includes evaluating and puts within reach therapeutic strategies that may mitigate these effects. Currently, in most of these centers, little sexological intervention is performed. This could be due to the little training of the people who work in these facilities in this respect, the limited time that one can spend on issues that are outside of substance consumption, or the resistance of patients to talking about these issues. Although, over time, the substance is no longer present in the body, the behaviors learned over years of consumption are maintained, probably being the reason behind that the sexual response does not improve with abstinence.

Regarding the erotophilia-erotophobia dimension, people who have had a history of use obtained lower mean scores on the SOS, so they are more erotophobic. Previous research shows that sexual attitudes are positively related to sexual satisfaction (Sánchez-Fuentes, Santos-Iglesias, & Sierra, 2014). It seems logical that men with the highest average score on the ED scale have greater resistance to having sexual encounters with potential mates, fear and anxiety that can cause them to fail in sexual encounters. It is also assumed that people who feel more secure in their relationships (suffer less ED) may tend to look more actively and be more open to new experiences (more erotophilic) than people who are feel more insecure. Similar results were found when erotophobia among women with a history of use and women with no history of use was analyzed (Del Río, Cabello, Cabello, & Lopez, 2012) as well in people with no history of substance use (Sierra et al., 2014).

As for anxiety, men who are substance users have greater anxiety on average than men who were not users. The relationship between substance use and anxiety is known (Cardoso-Moreno & Tomás-Aragonés, 2013; Charriau et al., 2013; Córdova & García, 2011). Men who are substance users scored statistically significantly higher on both state anxiety and trait anxiety than nonusers. Anxiety is an important factor in the development of different sexual dysfunctions including erectile dysfunction (Heiman & LoPiccolo, 2006; Lykins, Janssen, Newhouse, Heiman, & Rafaeli, 2012; Mosack et al., 2011).

The results also show that the kind of substance (stimulant, depressant or psychedelic) influences erectile response differently. Thus, men who have consumed depressants have a statistically significantly higher average score than men who have used stimulants. To date, there are few studies comparing the effects on sexual function depending on the kind of substance. Jiann's (2008) study, in which the influence of different substances is discussed in ED is noteworthy. This author concludes that different substances affect the erectile function of men, but does not indicate whether there is a substance that influences more than another, because, as indicated, we must be cautious in interpreting the results, since these are affected by different factors (psychological, physiological, environmental, cultural), not only by the substance consumed. The possible effects of substances used to adulterate the drugs of abuse should be added to the different factors that Jiann (2008) points out. Because of this, the conclusions from these data need to be taken cautiously.

Finally, it is found that variable of age influences erectile response. The result of this hypothesis is not surprising, since many studies examining age and sexual dysfunction point to a direct correlation between the two variables, i.e., the older the age, the higher the prevalence of sexual dysfunction (Bechara, Romano, & De Bonis, 2013; Sierra et al., 2014). Among the reasons it is argued that there are higher prevalences of other diseases (hypertension, diabetes, vascular disorders, musculoskeletal disorders, etc.), decreased libido, lack of vitamin B, the involvement of the vascular endothelium and decreased testosterone. Also, if one starts with the assumption that substance use affects sexual response, the longer that they were consumed (the older individuals may have a greater history of use) this should lead to greater impairment of the sexual response than with a short period of consumption. Although this research can not rule out this hypothesis, since it does not include data relating to the length of use to unravel which of the two variables have a greater influence.

Some of the limitations of this study should be noted. Such as the fact that data collection was carried out by different people. Information was collected by professionals in various treatment centers and although they had been previously given precise instructions on how to collect data, it could have been a variable which influenced the results. Another limitation has to do with the substances consumed by people in treatment for drug abuse. The information provided by those who seek treatment for drug addiction is not without bias, mainly for two reasons. The first is the fact that the person reporting on a substance that thinks is the main source of the problem (e.g. cocaine), without reporting, intentionally or not, the use of other substances (alcohol, cannabis) that may also influence their sexual behavior. Second, we must take into account that substances normally consumed are often adulterated with other active ingredients that the consumer has no information about, and these can also influence their behavior or have long-term effects. However this cannot be known because these are illicit substances. Therefore, it must be considered that the results are subject solely to the information the user provides regarding their history of consumption, with the imprecision that this could involve. Finally, it should also be considered a limitation that a higher percentage of substance users no partner than nonusers, as it could affect differentially on the answers provided, being a protective factor against different pathologies (Ross & Mirowsky, 2013; Zheng & Thomas, 2013).

The authors thank the following treatment centers for their participantion in this research: Centro de Solidaridad de Zaragoza Proyecto Hombre, Centro Español de Solidaridad de Córdoba - Proyecto Hombre, Centro Español de Solidaridad Proyecto Hombre Madrid, Comunidad Terapéutico O Confurco ASFEDRO, FGSVA Proyecto Hombre Granada, Fundación Alcandara Proyecto Hombre Salamanca, Fundación Aldaba Proyecto Hombre Valladolid, Fundación Ángaro Proyecto Hombre Jaén, Fundación Arzobispo Miguel Roca Proyecto Hombre Valencia, Fundación CALS Proyecto Hombre Bierzo-León, Fundación Canaria CESICA Proyecto Hombre, Fundación Candeal Proyecto Hombre Burgos, Fundación Centro de Solidaridad de La Rioja Proyecto Hombre La Rioja, Fundación CESPA Proyecto Hombre Asturias, Fundación Jeiki, Fundación Proyecto Hombre Navarra, Fundación Solidaridad y Reinserción Proyecto Hombre Murcia, Projecte Home Balears, Proyecto Hombre Almería, Proyecto Hombre Cantabria, Proyecto Hombre Castilla La Mancha, Proyecto Hombre Cataluña, Proyecto Hombre Extremadura, Proyecto Hombre Huelva, Proyecto Hombre Málaga CESMA, Proyecto Hombre Provincia de Cádiz and Proyecto Hombre Sevilla.

Available online 15 November 2014