Despite the theorized role of body checking behaviours in the maintenance process of binge eating, the mechanisms by which they may impact binge eating remain unclear. Using objectification model of eating pathology as a theoretical framework, the authors examined the potential intervening roles of body shame, appearance anxiety, and dietary restraint in the pathway between body checking and binge eating. Data collected from a large sample of treatment-seeking people with Bulimic-type Eating Disorders (N=801) were analysed trough structural equation modelling. Results showed that, regardless of specific DSM-5 diagnostic categories, body checking behaviours were indirectly associated with binge eating and dietary restraint through body shame and appearance anxiety, whereas dietary restraint was directly linked to binge eating. The findings have clinical utility as they contribute to gaining insight into how critical scrutiny of one's body may act in several indirect ways to affect binge eating. We discuss practical implications of the findings.

A pesar del papel teórico que desempeñan las conductas de comprobación corporal en el proceso de mantenimiento de la conducta de atracón, los mecanismos por los que pueden afectar a los atracones siguen sin estar claros. Tomando el modelo de la objetivación de la patología alimentaria como marco teórico, los autores examinaron las posibles funciones que desempeñan la vergüenza corporal, la ansiedad por la apariencia y la restricción alimentaria en la comprobación del cuerpo y los atracones. Los datos recogidos en una amplia muestra de pacientes con trastorno de tipo bulímico en busca de tratamiento (N=801) se analizaron a través de modelos de ecuaciones estructurales. Los resultados mostraron que, independientemente de las categorías diagnósticas específicas del DSM-5, las conductas de comprobación estaban asociadas indirectamente con los atracones y la restricción alimentaria a través de la vergüenza corporal y la ansiedad por la apariencia, mientras que la restricción alimentaria estaba directamente asociada con los atracones. Los resultados aportan utilidad clínica dado que contribuyen a la idea de cómo el examen crítico del propio cuerpo puede afectar de forma indirecta a las conductas de atracón. Se discuten las implicaciones prácticas de los hallazgos.

Body checking involves any behaviour aimed at gaining information about one's body size/shape or weight, such as excessive weighing, pinching of body parts to measure fatness, constant body comparisons with others, and repeated ritualistic measurements (Hilbert & Hartmann, 2013). Such behaviours reliably distinguish patients with eating disorders (EDs) from non-clinical samples and are of considerable interest to clinicians and researchers since they may negatively interfere with treatment, and their frequency is an indicator of ED severity (Ahrberg, Trojca, Nasrawi, & Vocks, 2011; Crowther & Williams, 2011; Fitzsimmons-Craft, Bardone-Cone, & Kelly, 2011; Hilbert & Hartmann, 2013).

There is now compelling evidence that not only individuals with bulimia nervosa (BN) are significantly more likely to critically scrutinize their own body than those with anorexia nervosa, but also that body checking is a clinical feature of all bulimic-type EDs (Crowther & Williams, 2011; Hilbert & Hartmann, 2013). These disorders include BN and its variants [bulimic-type ED not otherwise specified (EDNOS); i.e., EDs “clinically significant” but not meeting full DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for BN, or needing additional study, such as binge eating disorder (BED)] (Mond, 2013). Furthermore, various conceptualizations of binge eating highlight the role of body checking in the persistence of all bulimic-type EDs (e.g., Williamson, White, York-Crowe, & Stewart, 2004). However, existing research with bulimic-type ED patients has constantly failed to support any significant association between body checking and binge eating (i.e., overeating accompanied by a sense of loss of control while eating), although it has shown that the majority engage in body checking behaviours on a regular basis (e.g., Calugi, Dalle Grave, Ghisi, & Sanavio, 2006; Dakanalis, 2014; Fitzsimmons-Craft et al., 2011; Mountford, Haase, & Waller, 2007; Reas, Grilo, Masheb, & Wilson, 2005). Hence, the nature of the connection between body checking and binge eating, including the specific mechanism by which it may impact binge eating (i.e., the hallmark behaviour of all bulimic-type EDs; Mond, 2013), remains unclear to date.

It has been suggested that, for bulimic-type ED patients, repetitive body checking may stimulate or perpetuate existing negative emotions directed towards body and physical appearance (Reas et al., 2005). It is implicit that body checking may contribute to binge eating only indirectly in this hypothesis, although it does not address which specific emotional experiences would mediate the body checking-binge eating relationship (Dakanalis, 2014). Other ED scholars proposed dietary restraint as a potential mediator (Crowther & Williams, 2011). Indeed, research with bulimic-type ED patients consistently found a significant association between body checking and dietary restraint (e.g., Dakanalis, 2014; Mountford et al., 2007) that is often cited as a contributor of binge eating (see Stice & Presnell, 2010).

Although consistent with these hypotheses, the objectification model of eating pathology (Calogero, Tantleff-Dunn, & Thompson, 2011) offers a theoretical framework suitable for a better understanding of how body surveillance techniques (i.e., body checking) are translated into binge eating (Riva, Gaudio, & Dakanalis, 2015; Tiggemann, 2013). In fact, it postulates multiple co-occurring mechanisms of the influence of body checking on binge eating in which the role of both dietary restraint and specific emotional experiences related to one's body and physical appearance, are considered central (e.g., Dakanalis, Clerici et al., 2014; Dakanalis & Riva, 2013). According to the objectification model (Calogero et al., 2011) the hyper-focus on, and repeated monitoring of, one's whole body or body parts magnifies the perceived imperfections of the current body shape/size or weight and thereby serves to develop or maintain body shame and appearance anxiety (Tiggemann, 2013). Thus, both body shame and appearance anxiety are assumed (Calogero et al., 2011) to (a) trigger binge eating as a means of coping, and (b) motivate dietary restraint (that often includes the adoption of rigid dietary rules about eating and food), because of the common belief that this is an effective weight/shape-control technique (e.g., Dakanalis et al., 2013). In addition, in line with the cognitive-behavioural models of EDs (Williamson et al., 2004), the objectification model (Calogero et al., 2011) posits that due to the psychological and physiological effects of dietary restraint, all attempts to control eating are abandoned and a binge occurs when the inflexible adopted dietary rules, which are extremely difficult to maintain, are broken.

To summarize, the objectification model suggests that body shame, appearance anxiety, and dietary restraint serve as intermediate links in the chain leading from body checking to binge eating. Although a large body of research (see Tiggemann, 2013) supported the conceptual relationships of the objectification model in non-clinical samples, to our knowledge, no studies have directly tested this theoretical model in a clinical sample. It also remains unclear how well the model accounts for dietary restraint and binge eating, as they have always been operationalized as a single construct assessed via self-reported ED symptom composite measures.

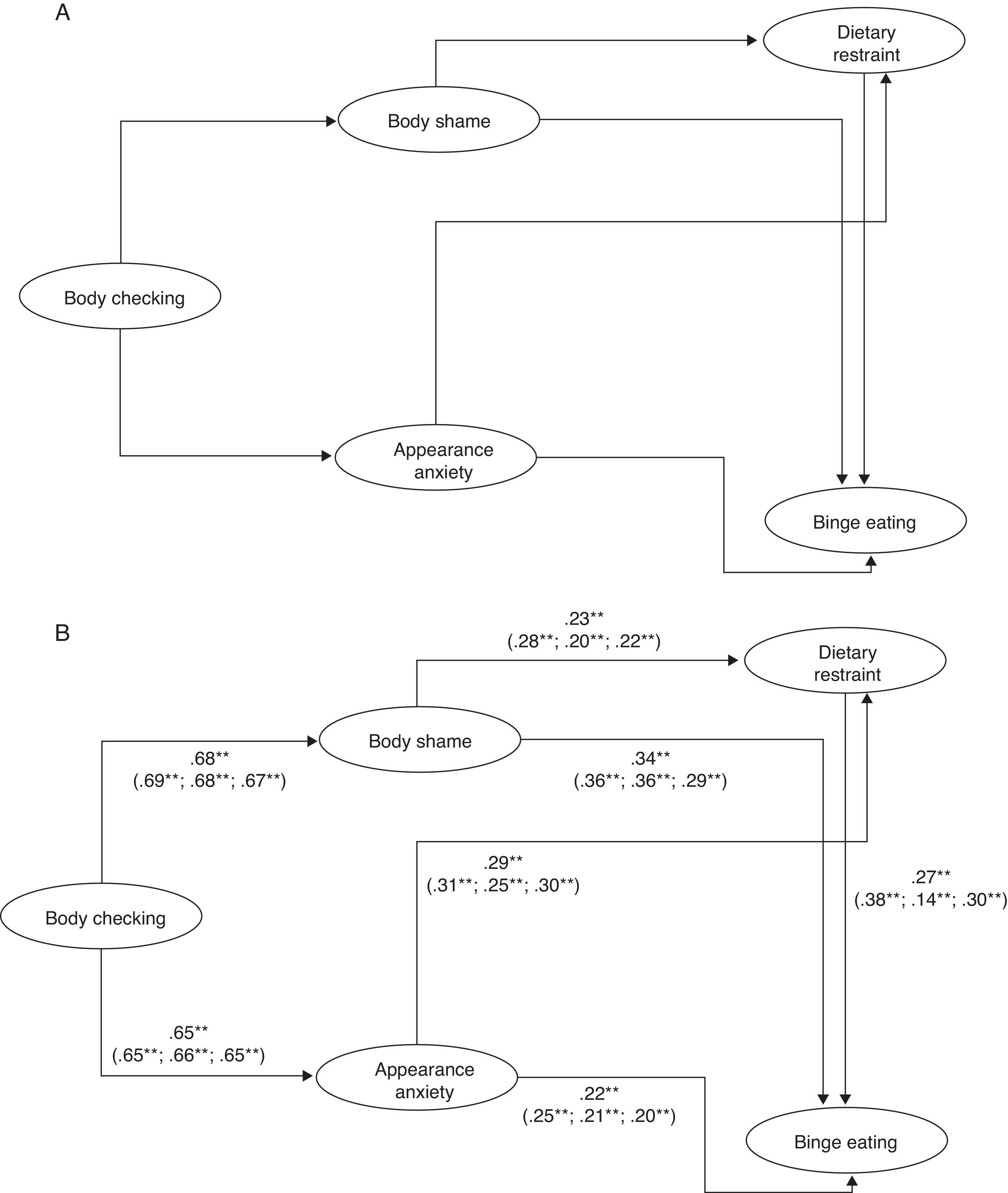

The current study aimed at extending research in this area by testing the mediating links between body checking and binge eating posited in the objectification model in a large clinical sample seeking treatment for BN or its variants (i.e., bulimic-type EDNOS). It was expected that the hypothesized model (Figure 1A), controlling for body mass index (BMI) and depression levels as covariates1 (Tiggemann, 2013), would provide a good fit to the observed data. We are also interested in exploring whether the strength of the conceptual relationships of the objectification model (see Figure 1A) is similar or different across diagnostic groups, as well as testing the significance of the indirect (or mediating) effects.

The hypothesized (A) and evaluated (B) objectification model for the total Bulimic-type Eating Disorder sample (N=801) with standardised coefficients. Ellipses represent unobserved latent variables. Observed/measured covariates in the model [i.e., body mass index and depression (Beck Depression Inventory score)] were estimated, but not depicted. The values in parentheses from left to right are the path coefficients for the structural model for each DSM-5 diagnostic group in the following order: Bulimia Nervosa, Binge Eating Disorder, and Bulimic-type Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified.

*p<.05; **p<.001.

The goal of this study is consistent with the call for theoretical grounded research aimed at advancing our understanding of the mechanism of the influence of body checking on binge eating and optimally informs both aetiological and intervention research (Hilbert & Hartmann, 2013). However, although the pathways between our model variables (see Figure 1A) were theoretically determined (i.e., they followed the order specified by the objectification model), it is plausible that other orderings of the model variables would provide a good fit to the data (Byrne, 2011). Consequently, in order to test the robustness of our hypothesized model (Figure 1A), we aimed at comparing it with two rival/competing (theory-driven) models (Byrne, 2011). The first rival model reversed the order of body checking, body shame and appearance anxiety from the hypothesized model (Figure 1A). That is, body shame and appearance anxiety were specified to predict body checking, which in turn was specified to predict dietary restraint and binge eating. The rationale of the examination of this model was that body checking behaviours may serve to alleviate body shame and appearance anxiety at least momentarily but the information derived from repeated body checking could increase the sense of perceived failure to control shape/size or weight, thereby stimulating disordered eating attitudes and behaviours, namely dietary restraint and binge eating (Ahrberg et al., 2011; Calugi et al., 2006). In the second rival model, dietary restraint and binge eating were specified to predict body checking, whereas the paths from checking behaviours to body shame and appearance anxiety remained the same as in our hypothesized model (Figure 1A). The rationale of the examination of this model was that although body checking may result in body shame and appearance anxiety, these rituals may be an effect of dietary restraint and/or binge eating (e.g., “I check to see if (a) binge eating has made me gain weight, (b) my body shape has changed as a result of restraint attempts”; Mountford et al., 2007, p. 2705).

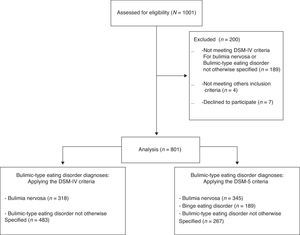

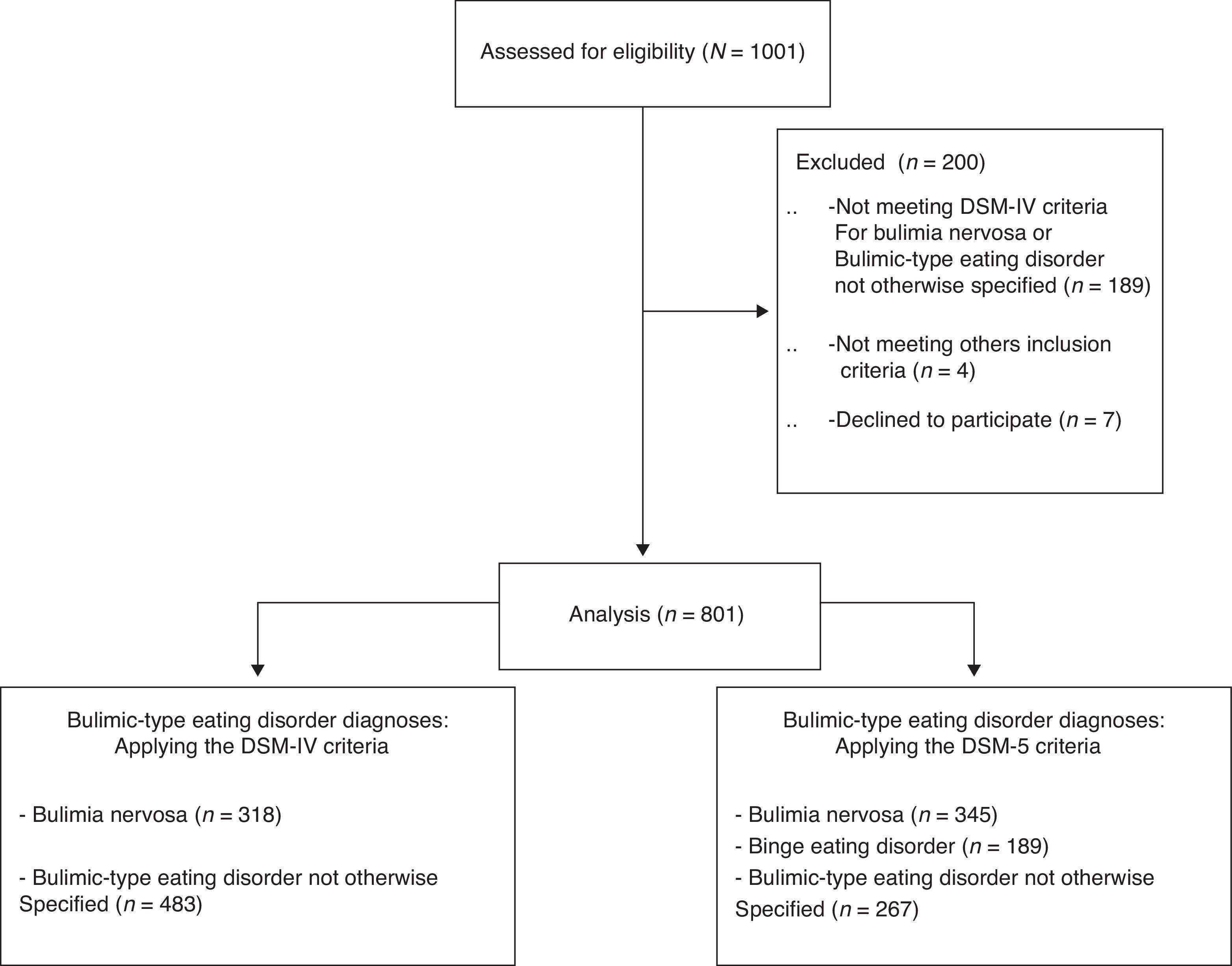

MethodParticipantsParticipants were drawn from a sample of 1,001 adults consecutively referred to, and assessed for, treatment of an ED at five medium-large sized Italian specialized care centres for EDs between March 2011 and June 2013. Though a portion of this data set has already been used to evaluate the role of insecure attachment in DSM-IV EDs (Dakanalis, Timko, Zanetti et al., 2014), there is no overlap between those results and those presented here. In this study, participants meeting DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, APA, 2000) diagnostic criteria for BN (n=318) or bulimic-type EDNOS (n=483), were included. Exclusion criteria comprised severe psychiatric conditions (psychosis), intellectual disabilities, concurrent treatment for body image disturbance, and insufficient knowledge of Italian. The flowchart of study participants is available in Figure 2. Diagnoses were assessed by means of the Italian Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I/P; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2000) and confirmed by findings from the Italian Eating Disorder Examination-Interview-12.0D2 (EDE; Mannucci, Ricca, Di Bernardo, & Rotella, 1996), which was also administered to assess both dietary restraint and frequency of binge eating episodes (see “instruments” below).

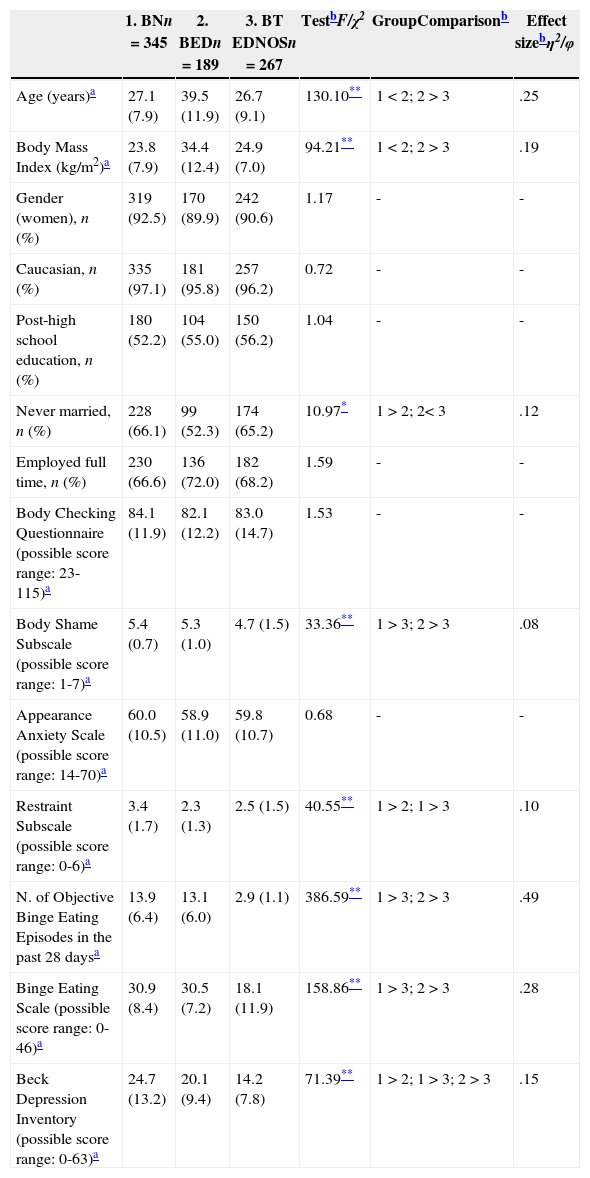

Using the interview records, all cases initially diagnosed as BN and bulimic-type EDNOS according to DSM-IV (APA, 2000) criteria were re-categorized post hoc using the new DSM-53 (American Psychiatric Association, APA, 2013) criteria (see Figure 2), as described elsewhere4 (Machado, Goncalves, & Hoek, 2013). The sample considered for analyses (N=801) comprised individuals with a DSM-5 diagnosis of BN (n=345), BED (n=189), and bulimic-type EDNOS5 (n=267). The socio-demographic characteristics stratified by diagnoses are shown on Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample.

| 1. BNn=345 | 2. BEDn=189 | 3. BT EDNOSn=267 | TestbF/χ2 | GroupComparisonb | Effect sizebη2/φ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)a | 27.1 (7.9) | 39.5 (11.9) | 26.7 (9.1) | 130.10** | 1<2; 2>3 | .25 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2)a | 23.8 (7.9) | 34.4 (12.4) | 24.9 (7.0) | 94.21** | 1<2; 2>3 | .19 |

| Gender (women), n (%) | 319 (92.5) | 170 (89.9) | 242 (90.6) | 1.17 | - | - |

| Caucasian, n (%) | 335 (97.1) | 181 (95.8) | 257 (96.2) | 0.72 | - | - |

| Post-high school education, n (%) | 180 (52.2) | 104 (55.0) | 150 (56.2) | 1.04 | - | - |

| Never married, n (%) | 228 (66.1) | 99 (52.3) | 174 (65.2) | 10.97* | 1>2; 2< 3 | .12 |

| Employed full time, n (%) | 230 (66.6) | 136 (72.0) | 182 (68.2) | 1.59 | - | - |

| Body Checking Questionnaire (possible score range: 23-115)a | 84.1 (11.9) | 82.1 (12.2) | 83.0 (14.7) | 1.53 | - | - |

| Body Shame Subscale (possible score range: 1-7)a | 5.4 (0.7) | 5.3 (1.0) | 4.7 (1.5) | 33.36** | 1>3; 2>3 | .08 |

| Appearance Anxiety Scale (possible score range: 14-70)a | 60.0 (10.5) | 58.9 (11.0) | 59.8 (10.7) | 0.68 | - | - |

| Restraint Subscale (possible score range: 0-6)a | 3.4 (1.7) | 2.3 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.5) | 40.55** | 1>2; 1>3 | .10 |

| N. of Objective Binge Eating Episodes in the past 28 daysa | 13.9 (6.4) | 13.1 (6.0) | 2.9 (1.1) | 386.59** | 1>3; 2>3 | .49 |

| Binge Eating Scale (possible score range: 0-46)a | 30.9 (8.4) | 30.5 (7.2) | 18.1 (11.9) | 158.86** | 1>3; 2>3 | .28 |

| Beck Depression Inventory (possible score range: 0-63)a | 24.7 (13.2) | 20.1 (9.4) | 14.2 (7.8) | 71.39** | 1>2; 1>3; 2>3 | .15 |

Note. BN=Bulimia Nervosa; BED=Binge Eating Disorder; BT-EDNOS=Bulimic-type Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified.

Differences for continuous variables among the diagnostic groups were assessed, using analysis of variance (df=2, 798); for categorical variables, χ2 was adopted (df=2). All post-hoc pairwise comparisons reported were significant at p<.016 (adjusted) or less. The appropriate measures of effect size for continuous [partial η2: small (.01–.09), medium (.10–.24), large (≥ .25)] or categorical variables [Cramer’ s φ with df=2: small (.07–.20), medium (.21–.34), large (≥ .35)] are reported.

Selective scales/subscales of standardized instruments with well-established psychometric proprieties among Italian ED patients were used in the current study.

Dietary Restraint. The Italian EDE (Mannucci et al., 1996) is an investigator-based interview that, in addition to the diagnostic items, provides information regarding the frequency of different forms of overeating, including objective bulimic episodes (OBEs; loss of control over eating and consumption of an objectively large amount of food), and generates four subscales (i.e., restraint, shape, weight, and eating concern) focusing on the previous 28 days. In the current study, the EDE 5-item Restraint subscale provided a measure of dietary restraint.

Binge Eating. Following relevant recommendations (e.g., Dakanalis, Carrà, Calogero, Zanetti et al., 2014; Ricca et al., 2010), the number of OBEs (evaluated by means of the EDE; see above), and the Italian 16-item Binge Eating Scale (Ricca et al., 2010) that examines behavioural signs, cognitions, and feelings during a binge eating episode (i.e., guilt), were used for measuring the frequency and severity of binge eating, respectively.

Body Checking. The Italian 23-item Body Checking Questionnaire (Calugi et al., 2006) was included as the gold-standard measure of a range of body checking behaviours (Hilbert & Hartmann, 2013).

Appearance Anxiety. In line with prior objectification research (Tiggemann, 2013), the Italian 14-item Appearance Anxiety Scale-short version (Dakanalis, 2014), that examines worries about the body as a whole and body parts, but also negative evaluation of others, was used to measure appearance anxiety.

Body Shame. In line with scholars’ recommendations (Fitzsimmons-Craft et al., 2011), the 8-item Body Shame subscale of the Italian Objectified Body Consciousness Scale (Dakanalis, 2014) was included as the gold-standard measure of shame about one's body, including shape/size and weight (Tiggemann, 2013).

BMI and Depression (covariates in the model; see data analysis for details). Anthropometric measurements (weight, height) were made using standard calibrated electronic instruments (Dakanalis, Timko, Carrà et al., 2014), and BMI (kg/m2) was calculated. The Italian 21-item Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI) (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 2006) was used to assess depression levels (Dakanalis, Timko, Zanetti et al., 2014).

In our global sample (N=801), and also in each diagnostic group, the internal reliability (α) estimates of each standardized instruments described were ≥ .89.

ProcedureAt each participating centre, clinicians with at least 10 years’ experience in assessing and treating EDs conducted all interviews. The remaining standardized instruments were administrated in counterbalanced order to offset possible ordering effects. After study procedures were fully explained, all participants provided written, informed, consent before being triaged to a treatment program. The study was approved by the ethics review board of each local institution (i.e., participating site) and of the co-ordinating body of the project (UniPV).

Data analysisDifferences in demographic and clinical variables among DSM-5 diagnostic groups (i.e., BN, BED, bulimic-type EDNOS) were assessed by means of ANOVA or χ2 test, as appropriate, followed by post-hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction if needed (Reid, 2014). The appropriate measures of effect size (and cut-off conventions) for continuous and categorical variables are also reported (Reid, 2014). There were no missing data. To accomplish our aims, latent variable structural equation modelling (SEM) analyses were performed in Mplus 6.12 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2011) with a maximum likelihood approach (as pre-analysis of the data did not reveal any evidence for univariate and multivariate non-normality; Byrne, 2011).

Latent variable SEM involves estimation of a (a) measurement and (b) a structural model, while accounting for measurement error (Byrne, 2011). The measurement model tests the proposed measurement of study constructs by estimating factor loadings between observed/measured variables/indicators and underlying latent variables, using confirmatory factor analysis. In this study, the number of OBEs provided by the EDE and the Binge Eating Scale were used as dual observed indicators for the binge eating latent variable. As in latent variable SEM analyses at least two indicators for each latent variable are needed, and because of parcelling bypasses issues common to item-level data (see Byrne, 2011), the procedure outlined by Byrne (2011) was used to generate three observed indicators for each of the remaining study latent variable depicted in Figure 1A; the parcelling procedure is described in depth in our previous study (Dakanalis, Timko, Clerici, Zanetti, & Riva, 2014).

The structural model retains the components of the measurement model and tests the specified structural relationships between latent variables (i.e., the directional paths; Figure 1A). BMI and depression (BDI score) were (observed) covariates6 in the structural model and specified to predict each of the latent variables (Byrne, 2011). Criteria for good measurement and structural model fit were: comparative fit index and Tucker-Lewis Index values ≥.95, standardized root-mean-square residual values ≤.08, and root-mean-square error of approximation values ≤.06 (Byrne, 2011). The chi-square statistic (χ2) was also reported.

After testing the proposed measurement and structural (objectification) models in the entire diagnostically mixed sample, participants (N=801) were grouped according to specific diagnosis, and multi-group SEM analyses were performed to determine whether the factor loadings and structural paths values differed or were similar across DSM-5 diagnostic groups (i.e., to investigate measurement and structural invariance). Measurement and structural invariance is supported if the strength of the factor loadings and the path estimates are equivalent across groups, respectively. To test for invariance, constrained (i.e., measurement or structural parameters were fixed to be equal for the groups) and unconstrained (i.e., parameters were allowed to vary) models were compared using the Δχ2 (Byrne, 2011), with a non-significant Δχ2 indicating that model parameters are invariant across DSM-5 diagnostic groups. To test for the significance of the indirect (mediating) effects, the evaluated structural model (Figure 1B) was run in Mplus with 10000 bootstrap samples; if the 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals do not include zero, the indirect effect is statistically significant at p ≤ .05 (Byrne, 2011). The type of mediation (partial or full) for each DSM-5 diagnostic group was determined by whether or not there was a significant direct path in the evaluated structural model (Figure 1B); if there was a not significant direct path, then full mediation occurred (Byrne, 2011).

Finally, Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) comparisons (Vallejo, Tuero-Herrero, Núñez, & Rosário, 2014) were used to estimate similarity/dissimilarity between the hypothesized and the two rival structural models (holding BMI and depression levels as observed covariates); lower AIC and BIC values reflect the more parsimonious structural model with the better fit. These analyses were performed using the entire sample (N=801). If the results indicate that the rival model(s) reflect(s) the more parsimonious model(s), with the better fit as compared to our objectification structural model (Figure 1), then multi-group SEM analyses are performed.

ResultsDifferences in demographic characteristics and study measures among DSM-5 bulimic-type ED groups are summarized in Table 1.

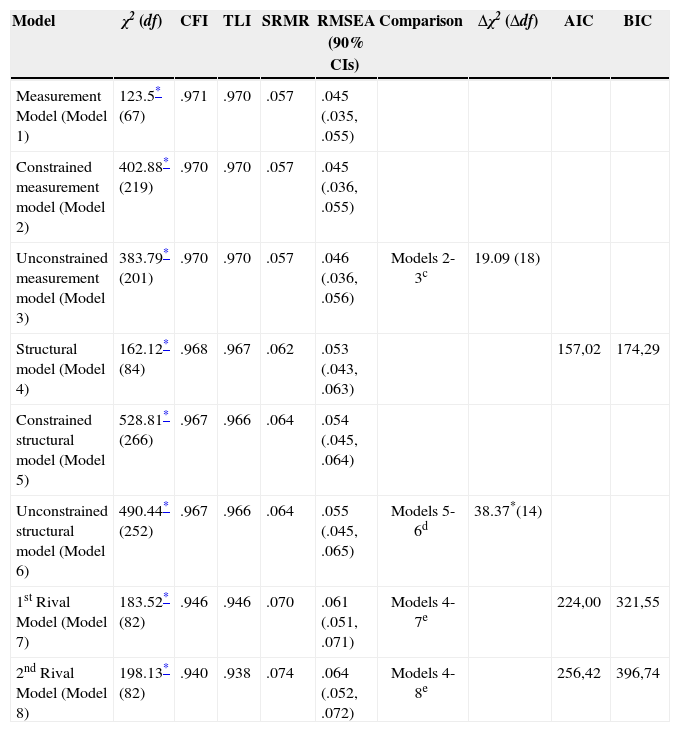

An initial test of the measurement objectification model resulted in a good fit to the entire sample data (Model 1, Table 2), and all loadings (ranging from .75 to .94)7* were significant (p<.001). The results of the multiple-group analysis revealed measurement invariance across diagnoses, as the difference in fit between constrained and unconstrained models was non-significant (Models 2-3, Table 2). Thus, all latent variables were adequately operationalized by their respective measured/observed indicators, and the measurement model was equivalent for DSM-5 groups.

Goodness-of-fit indices for the measurement and structural model, evaluation of measurement and structural invariance, and comparison of the objectification structural model to two alternative (rival) models.

| Model | χ2 (df) | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA (90% CIs) | Comparison | Δχ2 (Δdf) | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Model (Model 1) | 123.5* (67) | .971 | .970 | .057 | .045 (.035, .055) | ||||

| Constrained measurement model (Model 2) | 402.88* (219) | .970 | .970 | .057 | .045 (.036, .055) | ||||

| Unconstrained measurement model (Model 3) | 383.79* (201) | .970 | .970 | .057 | .046 (.036, .056) | Models 2-3c | 19.09 (18) | ||

| Structural model (Model 4) | 162.12* (84) | .968 | .967 | .062 | .053 (.043, .063) | 157,02 | 174,29 | ||

| Constrained structural model (Model 5) | 528.81* (266) | .967 | .966 | .064 | .054 (.045, .064) | ||||

| Unconstrained structural model (Model 6) | 490.44* (252) | .967 | .966 | .064 | .055 (.045, .065) | Models 5-6d | 38.37*(14) | ||

| 1st Rival Model (Model 7) | 183.52* (82) | .946 | .946 | .070 | .061 (.051, .071) | Models 4-7e | 224,00 | 321,55 | |

| 2nd Rival Model (Model 8) | 198.13* (82) | .940 | .938 | .074 | .064 (.052, .072) | Models 4-8e | 256,42 | 396,74 |

Note. χ2=chi-square; df=degrees of freedom; CFI=comparative fit index; TLI=Tucker-Lewis Index; SRMR=standardized root-mean-square residual; RMSEA=root-mean-square error of approximation; CIs= Confidence Intervals; Δ=difference values; AIC=Akaike information criterion; BIC=Bayesian information criterion.

aTesting for measurement (factor loading) invariance.

bTesting for structural invariance.

cComparison of the objectification structural model to two alternative (rival) models.

When the structural components of the objectification model were specified (Figure 1A), the results indicated that the model provided a good fit to the entire sample data (Model 4, Table 2), and all paths were significant (see Figure 1B). The model, controlling for covariates, accounted for 50.1% of the variance in body shame, 47.8% of the variance in appearance anxiety, 40% of the variance in dietary restraint, and 65.5% of the variance in binge eating. However, the multiple-group analysis revealed structural path differences (i.e., structural non-invariance) across the three DSM-5 bulimic-type ED groups, as the difference in fit between constrained and unconstrained models8 was significant (Models 5-6, Table 2). To pinpoint the source of the non-invariance (i.e., which structural path(s) was/were not invariant across groups), follow-up analyses were conducted by comparing the more restrictive (constrained) model (i.e., the model with structural path fixed to be equal) with seven different (unconstrained) models, each allowing only one of the structural paths (Figure 1B) to vary (Byrne, 2011). Chi-square difference tests indicated that the path from dietary restraint to binge eating was responsible for the non-invariance [Δχ2 (2)=28.24, p<.001]. Further comparisons of the constrained and unconstrained models in each pairs of diagnostic groups indicated that the dietary restraint-binge eating association was significantly greater in BN [Δχ2 (1)=17.45, p<.001] and bulimic-type EDNOS [Δχ2 (1)=12.02, p<.001] than in BED (see the structural coefficients in Figure 1B).

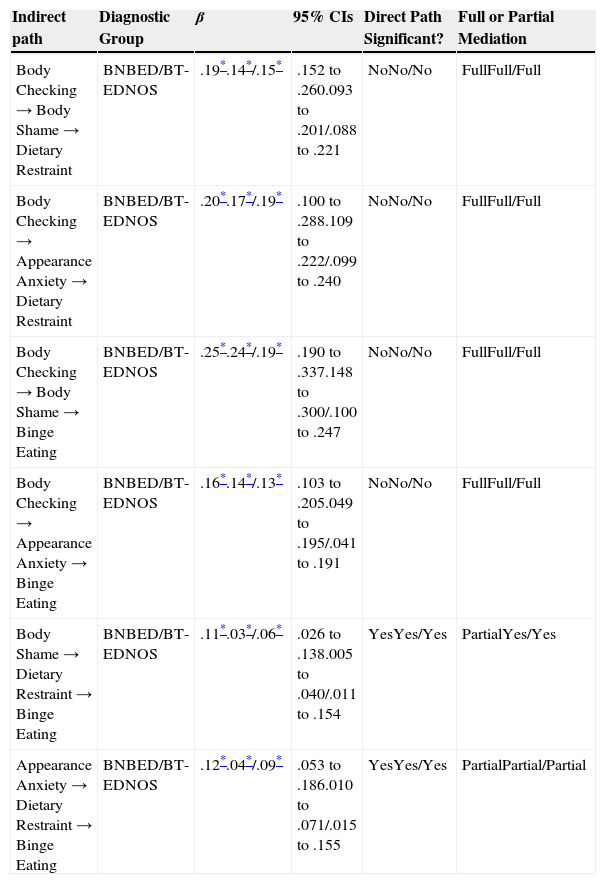

The bootstrap procedure showed that all indirect effects embedded within the structural objectification model (Figure 1B) were significant in each diagnostic group (Table 3). The type of mediation is also shown in Table 3.

Tests of mediation: examination of indirect effects (β), bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and significance of direct paths.

| Indirect path | Diagnostic Group | β | 95% CIs | Direct Path Significant? | Full or Partial Mediation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body Checking → Body Shame → Dietary Restraint | BNBED/BT-EDNOS | .19*.14*/.15* | .152 to .260.093 to .201/.088 to .221 | NoNo/No | FullFull/Full |

| Body Checking → Appearance Anxiety → Dietary Restraint | BNBED/BT-EDNOS | .20*.17*/.19* | .100 to .288.109 to .222/.099 to .240 | NoNo/No | FullFull/Full |

| Body Checking → Body Shame → Binge Eating | BNBED/BT-EDNOS | .25*.24*/.19* | .190 to .337.148 to .300/.100 to .247 | NoNo/No | FullFull/Full |

| Body Checking → Appearance Anxiety → Binge Eating | BNBED/BT-EDNOS | .16*.14*/.13* | .103 to .205.049 to .195/.041 to .191 | NoNo/No | FullFull/Full |

| Body Shame → Dietary Restraint → Binge Eating | BNBED/BT-EDNOS | .11*.03*/.06* | .026 to .138.005 to .040/.011 to .154 | YesYes/Yes | PartialYes/Yes |

| Appearance Anxiety → Dietary Restraint → Binge Eating | BNBED/BT-EDNOS | .12*.04*/.09* | .053 to .186.010 to .071/.015 to .155 | YesYes/Yes | PartialPartial/Partial |

Note. BN=Bulimia Nervosa; BED=Binge Eating Disorder; BT-EDNOS=Bulimic-type Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified.

Finally, as can been seen in Table 2, neither rival models provided a good fit to the entire bulimic-type ED sample data, and higher AIC and BIC values (Models 7-8) suggested that the objectification structural model (Model 4 in Table 2; Figure 1B) is preferable to the rival models. Thus, we did not conduct multi-group SEM (see data analysis).

DiscussionThe present study aimed at evaluating in a large sample of individuals with bulimic-type EDs the objectification model of eating pathology (Calogero et al., 2011), in an attempt to advance our knowledge about the underlying mechanisms of influence of body checking on binge eating. We found that (a) body checking behaviours were associated with increased body shame and appearance anxiety, which, in turn, were associated with increased dietary restraint and binge eating; (b) there was a direct path from dietary restraint to binge eating; (c) the objectification model fitted the data well and its robustness is further supported by the fact that the configuration of the rival models are not equally plausible and less ideal (Byrne, 2011); (d) with one exception (i.e., the direct path from dietary restraint to binge eating) differences across DSM-5 diagnostic groups on the strength of the associations amongst model variables (Figure 1B) were not observed. This last finding is highly important given increasing efforts to identify underlying aetiological and maintenance processes of eating pathology regardless of specific diagnostic categorisation (e.g., Dakanalis, Timko, Clerici et al., 2014), and to develop common psychological assessment and interventions (Dakanalis, Timko, Zanetti et al., 2014).

The finding indicating that body checking behaviours impacted binge eating only through body shame and appearance anxiety amongst bulimic-type ED patients is in accordance with the objectification model of eating pathology, which postulates that binge eating has a regulatory function and occurs in order to reduce or cope with negative emotional experiences surrounding the body and physical appearance (Calogero et al., 2011). Our data are also consistent with extant studies amongst bulimic-type ED patients indicating the lack of a significant association between body checking and binge eating (e.g., Calugi et al., 2006; Dakanalis, 2014; Mountford et al., 2007; Reas et al., 2005). However, this study expanded them, as it contributes to gaining insight into how body checking behaviours may act in indirect ways to predict binge eating, highlighting the need for targeting the intervening variables in treatment programmes.

Body checking behaviours have also been found to affect dietary restraint (through body shame and appearance anxiety) which, in turn, is directly linked to binge eating. These results are in accordance with the objectification model of eating pathology (Calogero et al., 2011) and with previous, experimental studies showing that monitoring of one's body leads to increased negative emotional experiences towards body and physical appearance, predictive of later dieting practices (see Tiggemann, 2013). This pattern has also been confirmed in longitudinal studies (e.g., Dakanalis, Carrà, Calogero, Fida et al., 2014). Moreover, there is evidence that some bulimic-type ED patients deliberately monitored their body in order to induce a state of stress, anxiety and body discontent, increasing motivation to engage in dietary restraint, regardless of a net loss, gain, or stable weight (Dakanalis, 2014; Reas et al., 2005).

Overall, our findings on body shame and appearance anxiety in the association between body checking, dietary restraint and binge eating lend support to evidence showing that binge eating may be rooted in dietary restraint, negative affect, or some combination of the two (e.g., Crowther & Williams, 2011; Dakanalis, Timko, Carrà et al., 2014; Stice & Presnell, 2010). Although significant differences among DSM-5 diagnostic groups were observed in direct association between dietary restraint and binge eating, the weak, but significant, association found in the BED group (Figure 1B) is consistent with other studies indicating that moderate dietary restraint attempts may be a characteristic of BED (see Stice & Presnell, 2010). Nevertheless, the potential contribution of dietary restraint attempts to the maintenance of BED is, not fully understood, so far (Stice & Presnell, 2010).

To our knowledge, this was the first study evaluating in a large treatment-seeking sample for bulimic-type EDs the mechanisms by which body checking may impact binge eating. However, some limitations of the study should be acknowledged. First, despite complex data analytic procedures, the inclusion of certain covariates within SEM analyses, and the comparison of objectification model to two rival models, our findings need to be interpreted with caution, as the cross-sectional nature of our data precludes any firm conclusions about the sequence of model variables and does not allow examination of causal relationships and feedback maintenance loops within the model (i.e., if binge eating encourages further dietary restraint). Empirical testing of these loops would need an enhanced experimental and longitudinal design (Byrne, 2011). Second, although the inclusion of semi-structured interviews would reduce social desirability, the use of self-report measures of some constructs of interest is prone to relevant biases, and replication with other methods of data collection (e.g., ecological momentary assessment) would be beneficial. Finally, as noted in the method section, we re-categorized bulimic-type EDNOS cases previously diagnosed following DSM-IV criteria, before evaluating the mediating links between body checking and binge eating assumed in the objectification model of eating pathology. Although this is a standard procedure (Machado et al., 2013), it should be noted that participants were not interviewed again and we only relied on notes made during previous clinical interviews.

The role of body checking in the maintenance of bulimic-type EDs is significant (e.g., Fitzsimmons-Craft et al., 2011; Williamson et al., 2004) and many patients may not disclose their control behaviours to clinicians (because of shame or lack of awareness). Thus, it is essential that clinicians explore body checking behaviours when assessing/treating individuals with EDs (Tiggemann, 2013). The results of this study also highlight the importance of assessing body shame and appearance anxiety. Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) is considered the treatment of choice for binge eating problems (Hay & Claudino, 2010). Although CBT implements body checking interventions as a matter of course, remissions involve only 40-50% of patients and it is more effective in reducing ED behavioural symptoms rather than producing changes in body image disturbance (e.g., Crowther & Williams, 2011; Ferrer-García & Gutiérrez-Maldonado, 2012; Hay & Claudino, 2010). However similar disturbances seem playing a major role in the persistence and relapse processes of bulimic-type EDs (e.g., Dakanalis, Carrà, Calogero, Zanetti et al., 2014; Hilbert & Hartmann, 2013). In particular CBT does not address the emotional experiences directed toward one's body and physical appearance (i.e., body shame, appearance anxiety) (Ahrberg et al., 2011; Crowther & Williams, 2011; Ferrer-García & Gutiérrez-Maldonado, 2012) that, according to our results, may be important targets. Therefore, the use of standard CBT interventions in combination with other promising approaches (i.e., virtual reality, exposure techniques) designed to address body image and weight-related problems, might be an important venue in order to decrease binge eating and improve treatment outcomes (Ahrberg et al., 2011; Crowther & Williams, 2011; Ferrer-García & Gutiérrez-Maldonado, 2012; Hilbert & Hartmann, 2013; Riva, Gaggioli, & Dakanalis, 2013; Riva et al., 2015).

FundingThe work was supported by a grant from the Onassis Foundation (O/RG 12410/GH23). The authors report no declarations of financial interest. Special appreciation is expressed to all participants and their parents.

Available online 14 April 2015

This was done in an attempt to reduce the potential effects of BMI and depression on the relationships between the variables under investigation (Figure 1A; Tiggemann, 2013).

Inter-rater reliability for DSM-IV diagnoses was determined by having two randomly selected samples of 30% of the SCID-I/Ps (κ = 1.0) and 30% of the EDEs (κ = 1.0) that were conducted at each participating site rated by assessors at the other site.

This was done, since prior to the completion of the study, APA Task Force made several changes to ED diagnoses in the DSM-5 (APA, 2013) in order to reduce the preponderance of the DSM-IV (APA, 2000) anorexic and bulimic-type EDNOS categories (Rodríguez-Testal, Senín-Calderón, & Perona-Garcelán, 2014) that formed the most common ED among those seeking treatment (Mond, 2013). With respect to DSM-IV bulimic-type EDs these changes included: (a) reduction of minimum binge/compensatory behaviour frequency for a diagnosis of BN from twice to once per week over the past 3 months, (b) elimination of the scheme distinguishing purging and non-purging subtypes, (c) designation of BED as a separate diagnosis with a minimum frequency of binge eating occurring once per week over a 3-month period (for details, see Mond, 2013). In DSM–IV (APA, 2000), BED was one of the examples of bulimic-type EDNOS and its provisional criteria required binge eating 2 days per week for 6 months.

DSM-5 post-hoc re-categorization of all cases initially diagnosed according to the DSM-IV was made by two independent clinicians with excellent knowledge of both DSM-IV and DSM-5 classification systems (κ = 1.0). The proportion of identified bulimic-type EDNOS cases based on DSM-IV criteria, dropped from 60.3% to 33.3% (related samples Wilcoxon signed rank test, p < .001) when DSM-5 criteria were used. As shown in Figure 2, among the initial 483 DSM-IV bulimic-type EDNOS cases, 27 were reclassified as BN and 189 as BED. The reduction rate (27%) found in our treatment-seeking sample converged with that of prior studies (26.5-28.6%), even though they employed clinical samples under treatment or people suffering from an ED recruited from the community (Dakanalis, Carrà, Calogero, Zanetti et al., 2014; Machado et al., 2013). Moreover, these studies, consistent with our findings, showed that the recognition of BED as a formal ED in the DSM-5 (APA, 2013) was the main source of the reduction of the preponderance of the DSM-IV (APA, 2000) EDNOS category.

Although DSM-5 (APA, 2013) also changed the EDNOS designation to Other Specified Feeding or ED, for simplicity, in the current manuscript we used the term “bulimic-type EDNOS” (Mond, 2013) to refer to bulimic-type diagnoses that fell into the Other Specified Feeding or ED group.

In our SEM analyses, we did not control for any other variable (Table 1), since, preliminary analyses indicated that they were unrelated to scales/subscales used to specify our latent variables.

Factor/parcel, factor loadings and correlations among the measured/observed and latent variables for diagnostic groups are available from the corresponding author on request. Modification indices provided by Mplus were detected in both the measurement and structural models but their magnitude (< 5.0) suggested that any non-originally specified parameters did not impact the fit of each model to the data (Byrne, 2011).

In each model, factor loadings between the groups were held invariant. However, error variances and path coefficients from the covariates to the latent variables were allowed to vary across groups (Byrne, 2011).

![The hypothesized (A) and evaluated (B) objectification model for the total Bulimic-type Eating Disorder sample (N=801) with standardised coefficients. Ellipses represent unobserved latent variables. Observed/measured covariates in the model [i.e., body mass index and depression (Beck Depression Inventory score)] were estimated, but not depicted. The values in parentheses from left to right are the path coefficients for the structural model for each DSM-5 diagnostic group in the following order: Bulimia Nervosa, Binge Eating Disorder, and Bulimic-type Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified. *p<.05; **p<.001. The hypothesized (A) and evaluated (B) objectification model for the total Bulimic-type Eating Disorder sample (N=801) with standardised coefficients. Ellipses represent unobserved latent variables. Observed/measured covariates in the model [i.e., body mass index and depression (Beck Depression Inventory score)] were estimated, but not depicted. The values in parentheses from left to right are the path coefficients for the structural model for each DSM-5 diagnostic group in the following order: Bulimia Nervosa, Binge Eating Disorder, and Bulimic-type Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified. *p<.05; **p<.001.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/16972600/0000001500000002/v4_201507310034/S1697260015000083/v4_201507310034/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)