This study examined English- and Spanish-speaking psychologists’ and psychiatrists’ opinions regarding problematic, absent and stigmatizing diagnoses in current mental disorders classifications (ICD-10 and DSM-IV), and their perceived need for a national classification of mental disorders. Answers to open-ended questions included in WHO-WPA and WHO-IUPsyS surveys were examined using an inductive content-analysis method. A total of 3,222 participants from 35 countries were included. The most problematic diagnostic group was personality disorders, especially among psychiatrists, because of poor validity and lack of specificity. Complex posttraumatic stress disorder was the most frequent diagnosis suggested for inclusion, mainly by psychologists, to better account for the distinct processes and consequences of complex trauma. Schizophrenia was the diagnosis most frequently identified as stigmatizing, particularly by psychiatrists, due to lack of public understanding or knowledge about the diagnosis. Of the 14.4% of participants who perceived a need for a national classification system, two-thirds were from Africa or Latin America. The rationales provided were that mental disorders classifications should consider cultural and socio-historical diversity in the expression of psychopathology, differences in the perception of what is and is not pathological in different nations, and the existence of culture-bound syndromes. Implications for ICD-11 development and dissemination are discussed.

Se examinaron las opiniones de psicólogos y psiquiatras de habla inglesa y española acerca de los diagnósticos problemáticos, ausentes y estigmatizantes en la CIE-10 y DSM-IV, y de la necesidad de una clasificación nacional. Se llevó a cabo un análisis de contenido de las preguntas abiertas de las encuestas de WHO-WPA y WHO-IUPsyS. Se incluyeron a 3.222 participantes de 35 países. El grupo diagnóstico considerado más problemático fue trastornos específicos de la personalidad, especialmente entre psiquiatras, por la falta de validez y de especificidad. El trastorno por estrés postraumático complejo fue el diagnóstico que se sugirió incluir con mayor frecuencia, sobre todo por psicólogos, para dar cuenta de los procesos y consecuencias distintos del trauma complejo. La esquizofrenia fue el diagnóstico que se consideró más frecuentemente como estigmatizante, principalmente por psiquiatras, debido a la falta de conocimiento público. Del 14,4% que percibieron la necesidad de una clasificación nacional, dos tercios fueron de África o Latinoamérica. Las razones fueron que se debe considerar la diversidad socio-histórica en la expresión de psicopatología, las diferencias en la percepción de lo que es o no patológico, y la existencia de síndromes culturales. Se discuten las implicaciones para el desarrollo y difusión de la CIE-11.

In the ongoing development of the 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11) by the World Heath Organization (WHO), a major focus is to improve the clinical utility and cross-cultural applicability of mental and behavioural disorder diagnostic categories. General descriptions of the development of the ICD-11 classification of mental and behavioural disorders, the importance of clinical utility as a part of this effort, and the specific relevance of the ICD-11 to psychologists have previously been published (International Advisory Group for the Revision of ICD-10 Mental and Behavioural Disorders, 2011; Reed, 2010). As described in these reports, psychologists and psychiatrists are key professional constituencies in WHO's development of the ICD-11, as they come into contact with persons in need of mental health services on a daily basis, and represent particularly critical groups in the diagnosis and management of mental disorders. In order to improve the clinical utility of the ICD, it is essential to assess these professionals’ attitudes and opinions regarding diagnostic classification systems (Evans et al., 2013; Reed, Correia, Esparza, Saxena, & Maj, 2011).

Surveys of clinicians are among the most feasible and direct methods of obtaining relevant information from health professionals around the world. Several studies have used surveys to assess the attitudes and views of mental health professionals regarding diagnostic classification systems for mental disorders, mainly among psychiatrists (Bell, Sowers, & Thompson, 2008; Mellsop, Banzato, & Shinfuku, 2008; Mellsop, Dutu, & Robinson, 2007; Suzuki et al., 2010; Zielasek et al., 2010). However, the findings of these studies typically have limited generalizability due to limitations in sample size, methodology, and/or specificity of the geographical regions assessed.

To overcome these limitations, WHO developed two global surveys in the context of the development of the ICD-11 classification of mental and behavioural disorders, the first designed for psychiatrists and conducted in collaboration with the World Psychiatric Association (WPA) (Reed et al., 2011), and the second designed for psychologists and conducted in collaboration with the International Union of Psychological Science (Evans et al., 2013). These surveys examined psychiatrists’ and psychologists’ attitudes and experiences with diagnostic classification systems, focusing on conceptual and practical issues in mental disorder classification systems as encountered in psychiatrists’ and psychologists’ daily clinical practice.

A total of 4887 psychiatrists from 44 countries and 2155 psychologists from 23 countries participated. Reed and colleagues (2011) found that psychiatrists indicated that the most important purposes of a classification are to facilitate communication among clinicians and to inform treatment and management. Psychiatrists preferred a simpler system with 100 or fewer categories, as well as flexible guidance on diagnostic definitions compared to a strict criteria-based approach. They expressed some problems with the cross-cultural applicability of existing classifications (especially psychiatrists from Latin American and Asian countries) and reported several categories with poor utility in clinical practice (such as vascular dementia, schizotypal disorder, schizoaffective disorder, mixed anxiety and depressive disorder, adjustment disorder, dissociative disorders and somatoform disorders).

Evans and colleagues (2013) found that sixty percent of global psychologists routinely used a formal classification system (ICD-10 by 51% and DSM-IV by 44%). Psychologists viewed informing treatment decisions and facilitating communication as the most important purposes of classification; preferred flexible diagnostic guidelines to strict criteria; identified a number of problematic diagnoses (such as Asperger's syndrome, borderline personality disorder, dissociative disorders, somatoform disorders, and schizoaffective disorder); and reported problems with cross-cultural applicability and cultural bias (especially those from outside the USA and Europe).

Taken together, these two studies provide a great deal of useful information for informing the development of ICD-11. However, the initial published reports focused largely on quantitative results and did not explore the qualitative explanations behind clinicians’ responses. The surveys included additional, qualitative questions that can provide further insight into mental health professionals’ perceptions regarding problematic, absent, and stigmatizing diagnoses, as well as the perceived need for national classifications of mental disorders. The present study is an analysis of the qualitative rationales behind clinicians’ opinions, undertaken in order to further inform the development of the ICD-11 classification of mental and behavioural disorders.

Based on results from the initial studies on clinicians’ views of the ease of use and goodness of fit of ICD-10 and DSM-IV diagnostic classification systems (Evans et al., 2013; Reed et al., 2011), the main reason that a diagnosis is perceived as problematic is likely to be due to problems in its utility as currently formulated. With respect to stigmatizing diagnoses, we were particularly interested in schizophrenia, one of the most severe and disabling mental disorders. According to previous literature in the field, it is likely to be perceived by clinicians as a highly stigmatizing diagnosis, especially due to historical conventional stereotypes related to “split personality” (Nunnally, 1961) and violent behavior as the most outstanding features of the disorder (Pescosolido, Monahan, Link, Stueve, & Kikuzawa, 1999). Further, such stigmatization might be due primarily to a lack of knowledge and experience related to the disorder among the general public, which can contribute to negative attitudes and discrimination (Thornicroft, Rose, Kassam, & Sartorius, 2007).

Regarding diagnoses that clinicians believed should be added to existing classification systems and their perceived need for a national classification, we expected that clinicians would suggest the inclusion of cultural syndromes and would argue that cultural differences are important in the presentation and perception of psychopathology. Item by item comparisons of country-level or regional adaptations of the ICD-10 (First, Reed, Robles & Medina-Mora, 2014; Rivas, Reed, First & Ayuso-Mateos, 2011), suggest that many of the modifications that have been made in these systems relate to the addition of cultural phenomena. For example, the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders, Version 3 (Chen, 2002) has added the category “mental disorders related to culture” and the Cuban and the Latin American adaptations of ICD-10 (Asociacion Psiquiátrica de América Latina, 2004; Otero-Ojeda, 1998) include a number of “cultural syndromes” believed to be prevalent in these regions.

The principal aim of the present study was to examine English- and Spanish-speaking psychologists’ and psychiatrists’ opinions regarding problematic, absent and stigmatizing diagnoses in current mental disorders classifications (ICD-10 and DSM-IV), and their perceived need for a national classification of mental disorders. WHO is committed to conducting all studies related to the ICD revision in at least two languages—English and Spanish (see Reed, Anaya, & Evans, 2012)—as well as in other languages when possible. English and Spanish were by far the most widely used languages in the two studies that provided the data for the present analysis. A secondary aim of this study was to examine differences between psychiatrists and psychologists in their opinions regarding diagnostic categories, as well as geographical differences among WHO's global regions.

MethodThe procedures for the development and administration of the WHO-WPA and WHO-IUPsyS global surveys have been described in detail in previously published articles (Evans et al., 2013; Reed et al., 2011). The WHO Research Ethics Review Committee as well as applicable local Institutional Review Boards reviewed and approved all procedures used in these studies. Both surveys were developed in English and translations of the WHO-WPA survey into eighteen additional languages and of the WPA-IUPsyS survey into four additional languages were completed using an explicit translation methodology that included forward and back translation and resolution of differences among translators. Both the WHO-WPA survey and the WHO-IUPsyS survey were translated into Spanish by WHO.

Participants were recruited through their national psychiatric or psychological associations, which sent an initial solicitation and two reminder messages by Large professional associations (1000 or more members) were asked to randomly select 500 eligible members to solicit for participation. Smaller associations (less than 1000 members) were asked to solicit all eligible members. Participants were eligible for the study if they had completed their training as psychiatrists of psychologists, were authorized to provide mental health services to patients in their countries, and agreed to participate in the study. The survey was prepared for administration in different languages via the Internet using the Qualtrics electronic survey platform (see www.qualtrics.com). When the respondent clicked on the link embedded in the e-mail solicitation (or entered the Internet address in his or her web browser), he or she was directed to a page that explained the purpose of the survey, its anonymous and voluntary nature, the time required, and its exemption by the WHO’ Research Ethics Review Committee. The survey was administered based on participants’ agreement to participate.

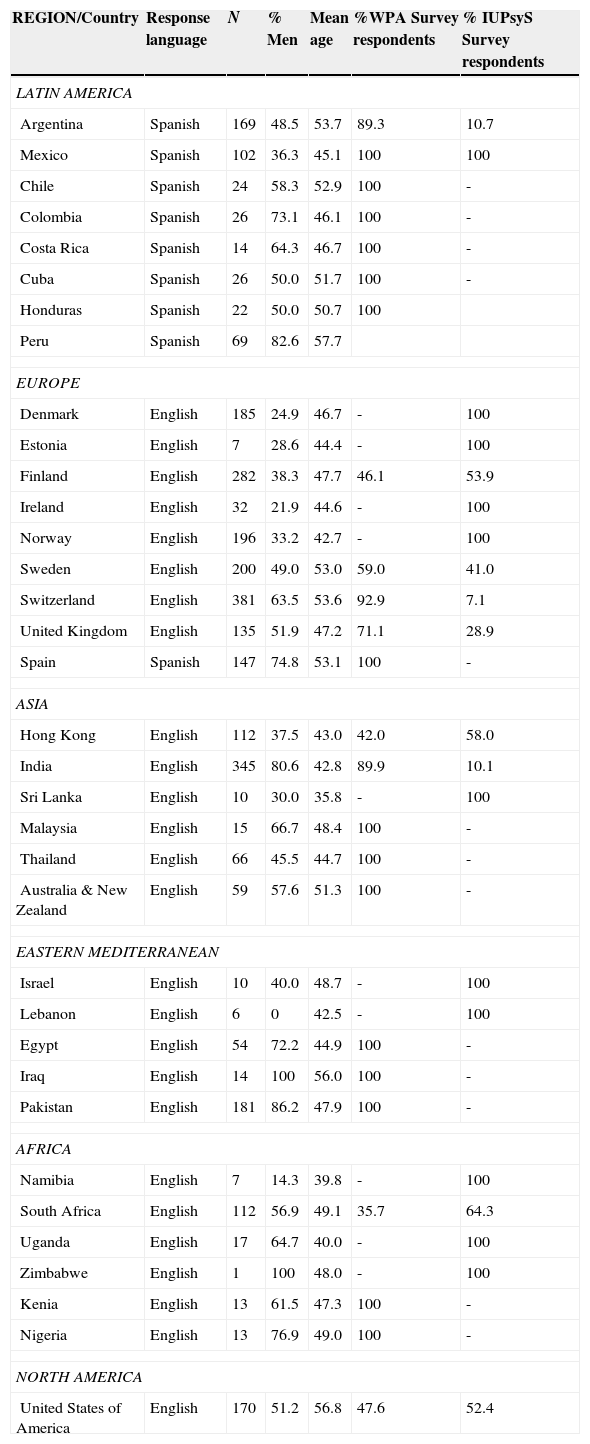

ParticipantsParticipants in the WPA-WHO survey were 4887 psychiatrists from 44 countries. The WHO-IUPsyS sample included 2155 psychologists from 23 countries. The sample for the present study was derived from the combined WHO-WPA and WHO-IUPsyS surveys (N=7042). Participants were included only if they responded in English or Spanish and had answered at least one of the four questions that allowed for open-ended responses. A total of 3895 participants from 35 countries (see Table 1) responded to the respective survey in English or Spanish (55.3% of the total combined sample). Of the participants who responded in English or Spanish, 673 (17.3%) did not answer any of the four open ended questions, or gave answers that were uninterpretable or not specific enough to analyze. Data from 3222 participants (82.7% of those who had responded in English or Spanish) were included in the present analysis.

Sample characteristics by country and region.

| REGION/Country | Response language | N | % Men | Mean age | %WPA Survey respondents | % IUPsyS Survey respondents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LATIN AMERICA | ||||||

| Argentina | Spanish | 169 | 48.5 | 53.7 | 89.3 | 10.7 |

| Mexico | Spanish | 102 | 36.3 | 45.1 | 100 | 100 |

| Chile | Spanish | 24 | 58.3 | 52.9 | 100 | - |

| Colombia | Spanish | 26 | 73.1 | 46.1 | 100 | - |

| Costa Rica | Spanish | 14 | 64.3 | 46.7 | 100 | - |

| Cuba | Spanish | 26 | 50.0 | 51.7 | 100 | - |

| Honduras | Spanish | 22 | 50.0 | 50.7 | 100 | |

| Peru | Spanish | 69 | 82.6 | 57.7 | ||

| EUROPE | ||||||

| Denmark | English | 185 | 24.9 | 46.7 | - | 100 |

| Estonia | English | 7 | 28.6 | 44.4 | - | 100 |

| Finland | English | 282 | 38.3 | 47.7 | 46.1 | 53.9 |

| Ireland | English | 32 | 21.9 | 44.6 | - | 100 |

| Norway | English | 196 | 33.2 | 42.7 | - | 100 |

| Sweden | English | 200 | 49.0 | 53.0 | 59.0 | 41.0 |

| Switzerland | English | 381 | 63.5 | 53.6 | 92.9 | 7.1 |

| United Kingdom | English | 135 | 51.9 | 47.2 | 71.1 | 28.9 |

| Spain | Spanish | 147 | 74.8 | 53.1 | 100 | - |

| ASIA | ||||||

| Hong Kong | English | 112 | 37.5 | 43.0 | 42.0 | 58.0 |

| India | English | 345 | 80.6 | 42.8 | 89.9 | 10.1 |

| Sri Lanka | English | 10 | 30.0 | 35.8 | - | 100 |

| Malaysia | English | 15 | 66.7 | 48.4 | 100 | - |

| Thailand | English | 66 | 45.5 | 44.7 | 100 | - |

| Australia & New Zealand | English | 59 | 57.6 | 51.3 | 100 | - |

| EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN | ||||||

| Israel | English | 10 | 40.0 | 48.7 | - | 100 |

| Lebanon | English | 6 | 0 | 42.5 | - | 100 |

| Egypt | English | 54 | 72.2 | 44.9 | 100 | - |

| Iraq | English | 14 | 100 | 56.0 | 100 | - |

| Pakistan | English | 181 | 86.2 | 47.9 | 100 | - |

| AFRICA | ||||||

| Namibia | English | 7 | 14.3 | 39.8 | - | 100 |

| South Africa | English | 112 | 56.9 | 49.1 | 35.7 | 64.3 |

| Uganda | English | 17 | 64.7 | 40.0 | - | 100 |

| Zimbabwe | English | 1 | 100 | 48.0 | - | 100 |

| Kenia | English | 13 | 61.5 | 47.3 | 100 | - |

| Nigeria | English | 13 | 76.9 | 49.0 | 100 | - |

| NORTH AMERICA | ||||||

| United States of America | English | 170 | 51.2 | 56.8 | 47.6 | 52.4 |

Of the 3222 participants included in this analysis, 2070 (64.2% were psychiatrists, and 1152 were psychologists (35.8%). The sample was 45.4% female, and participants’ average age was 48.8 years (SD=12), with an average of 16.1 (SD=11.1) years of professional experience following the completion of specialized training. Almost half of the respondents were from Europe (n=1565, 48.6%) followed by 18.8% (n=607) from Asia, 14% (n=452) from Latin America, 8.2% (n=265) from the Eastern Mediterranean region, 5.3% (n=170) from the U.S., and 5.1% (n=163) from Africa. Compared to the psychologist sample, the psychiatrist sample included a greater proportion of men (68.1% vs. 30.3%; χ2 (1)=425.2, p<.001), was generally older (psychiatrists: M=50.9 years, SD=11.8; psychologists: M=45.1 years, SD=11.5 years; t (3220)=13.5, p<.001) and reported having more years of clinical experience (psychiatrists: M=16.9, SD=11.2; psychologists: M=14.4, SD=10.7 years; t (3220)=5.3, p<.001). Participant characteristics by country and region are shown in Table 1.

A comparison of the participants who responded in English or Spanish and who were included in the present analysis (N=3222) with those who were not included (n=673), indicated that the average age of non-participants was slightly higher, an average of 50.5 years (SD = 12.03) for participants not included as compared to an average of 48.8 years (SD=11.4) for participants included in the present analysis (t (3983)=−3.41, p<001). Participants who were included in the present analysis did not differ from those who were not included in terms of gender, profession (proportion of psychologists vs. psychiatrists) or average years of clinical experience.

MeasuresThe original surveys (Evans et al., 2013; Reed et al., 2011) contained multiple choice, yes/no, and open-ended questions. Open-ended questions allowed participants to express their opinions in their own words, particularly for questions where it was believed that simple categorical response choices would not provide an adequate picture of their diverse clinical perspectives. These four questions, presented below, had a two-part structure beginning with a specific categorical (yes/no) question1.

- a

Are there diagnostic categories with which you are especially dissatisfied, or that you believe are especially problematic in terms of their goodness of fit in clinical settings?

- b

Are there any specific diagnostic categories that you feel should be added to the classification system for mental disorders?

- c

Do you think that any of the terms used in current diagnostic systems are stigmatizing in your language or cultural context?

- d

Do you see the need in your country for a national classification of mental disorders (i.e., a country-specific classification that is not just a translation of ICD-10)?

Participants who gave an affirmative answer were asked to explain (“If yes, please explain”), allowing them to describe the rationale for their answer according to their own clinical experience and point of view.

Data analysesOpen-ended data were coded using an inductive content-analysis method performed by two doctoral-level researchers (the first and second authors of the present article). For the items addressing problematic and stigmatizing diagnoses the existing ICD-10 diagnostic categories were used. Second, the reasons provided for all questions (including the question related to the need for a national classification) were read and summarized. Thereafter, themes and sub-themes were created and gradually reduced until they best described each given statement. After both researchers performed this procedure independently for 100% of the data, a consensus review was performed. If any discrepancy arose, adjustments were made until final meaning units were agreed upon. Agreement of coders—before the consensus review—was very high (kappa=.92, CI= 0.90–0.93). In addition to the descriptive overall results, data were compared between psychiatrists and psychologists and according to global region (Africa, Asia, Eastern Mediterranean, Europe, Latin America and North America; see Table 1) through Chi-square tests performed with SPSS-X version 20 for Windows, PC.

ResultsPerception of problematic diagnostic categoriesThe “yes/no” item for this question was presented to all participants. For those who responded to this item (n=3193, 99.1%), 45.9% (n=1465) responded “yes.” A greater proportion of psychiatrists (n=972, 47.6%) than psychologists (n=493, 42.9%) responded “yes” to this question (χ2 (1)=3.9, p=.01), indicating that they considered at least one diagnostic category to be problematic.

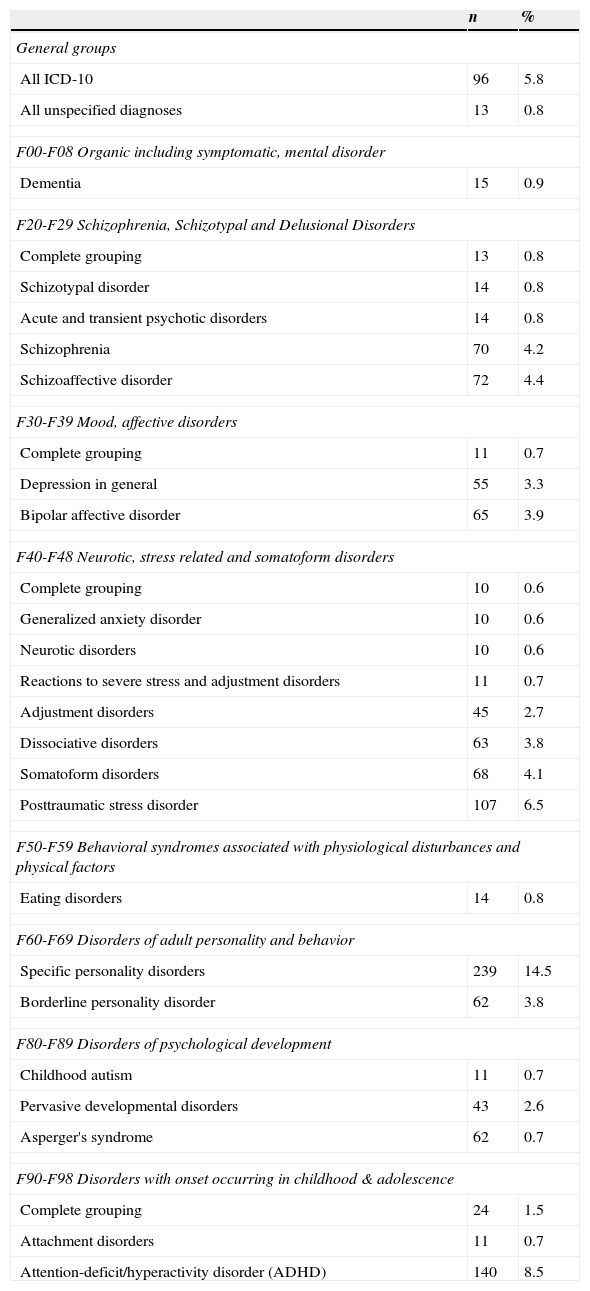

Of those professionals who responded “yes,” 1301 (88.8%) provided an explanation for their response in the open-ended follow-up question and were included in the content analysis. The remaining 164 (11.2%) participants who responded “yes” were not included in this content analysis because they did not give an explanation for their previous affirmation of the existence of problematic categories or gave responses that were too vague to be coded (e.g., “I think that categories should be changed”2; “too many to give any answer”). A total of 99 specific diagnoses were described as problematic. In addition, two general (nonspecific) response groups were identified, including those who referred to all diagnoses or general aspects of diagnosis (e.g., “too many criteria to diagnosis”, “the whole concept is unsatisfying”) or unspecified diagnoses (e.g., “most of the criteria that have a NOS category - which ends up being used as a dustbin for any diagnosis we are unable to fit in anywhere else”). Diagnoses that were mentioned by fewer than 10 participants were excluded from analyses. In total, 24 specific diagnoses were considered to be problematic or unsatisfactory in regular clinical practice, in addition to the two previously defined general response groups. Table 2 shows the number and percentage of respondents who described any specific diagnostic categories as problematic.

Diagnostic categories considered to be as problematic.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| General groups | ||

| All ICD-10 | 96 | 5.8 |

| All unspecified diagnoses | 13 | 0.8 |

| F00-F08 Organic including symptomatic, mental disorder | ||

| Dementia | 15 | 0.9 |

| F20-F29 Schizophrenia, Schizotypal and Delusional Disorders | ||

| Complete grouping | 13 | 0.8 |

| Schizotypal disorder | 14 | 0.8 |

| Acute and transient psychotic disorders | 14 | 0.8 |

| Schizophrenia | 70 | 4.2 |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 72 | 4.4 |

| F30-F39 Mood, affective disorders | ||

| Complete grouping | 11 | 0.7 |

| Depression in general | 55 | 3.3 |

| Bipolar affective disorder | 65 | 3.9 |

| F40-F48 Neurotic, stress related and somatoform disorders | ||

| Complete grouping | 10 | 0.6 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 10 | 0.6 |

| Neurotic disorders | 10 | 0.6 |

| Reactions to severe stress and adjustment disorders | 11 | 0.7 |

| Adjustment disorders | 45 | 2.7 |

| Dissociative disorders | 63 | 3.8 |

| Somatoform disorders | 68 | 4.1 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 107 | 6.5 |

| F50-F59 Behavioral syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors | ||

| Eating disorders | 14 | 0.8 |

| F60-F69 Disorders of adult personality and behavior | ||

| Specific personality disorders | 239 | 14.5 |

| Borderline personality disorder | 62 | 3.8 |

| F80-F89 Disorders of psychological development | ||

| Childhood autism | 11 | 0.7 |

| Pervasive developmental disorders | 43 | 2.6 |

| Asperger's syndrome | 62 | 0.7 |

| F90-F98 Disorders with onset occurring in childhood & adolescence | ||

| Complete grouping | 24 | 1.5 |

| Attachment disorders | 11 | 0.7 |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) | 140 | 8.5 |

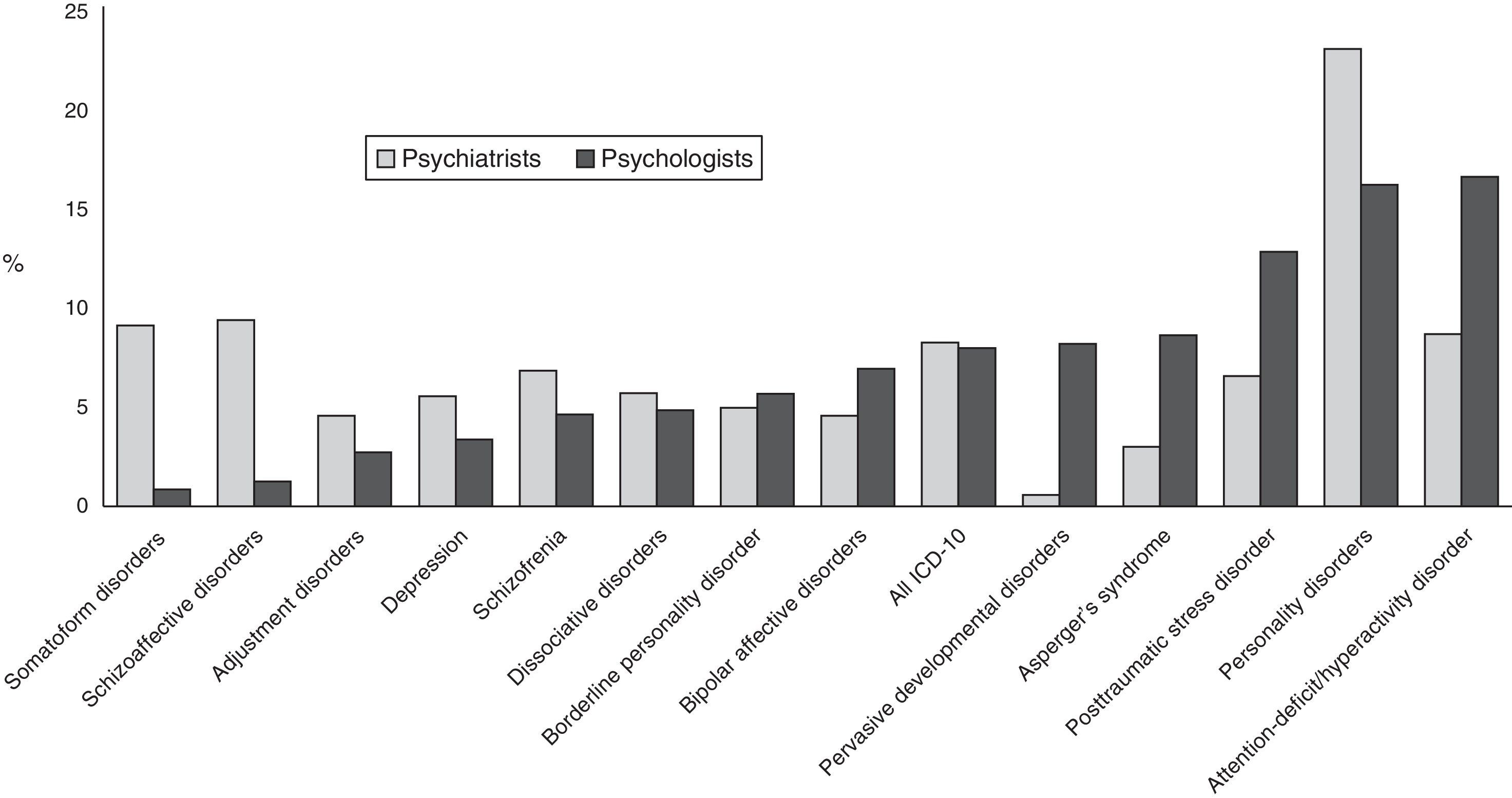

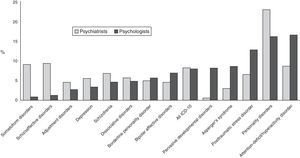

Perceptions of problematic diagnoses may differ between professionals from different disciplines. To examine this possibility, we compared the frequency with which psychologists and psychiatrists identified specific diagnostic categories as problematic. The diagnostic categories that were mentioned by at least 30 participants (psychologists or psychiatrists) are presented in Figure 1. A total of 1187 observations were included and grouped in 13 specific diagnoses and one general group

There were some differences by profession in the diagnoses described as problematic. A higher percentage of psychologists considered posttraumatic stress disorder, pervasive developmental disorders, and attention-deficit (hyperactivity) disorders as problematic when compared to psychiatrists. More psychiatrists than psychologists perceived schizoaffective disorder and somatoform disorders as problematic (χ2 (13)=171.8, p<.001).

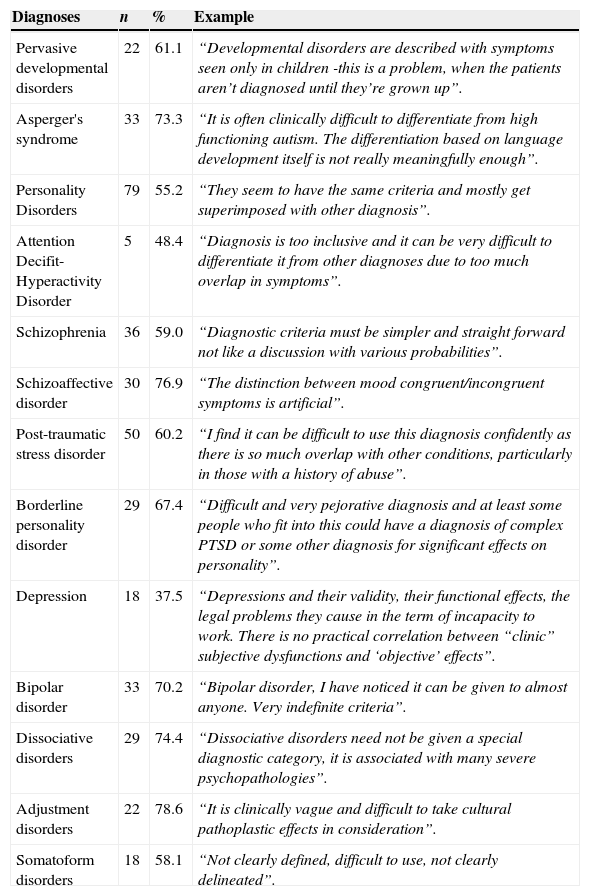

In about two-thirds of the responses (68.5%; n=813), participants went on to explain the reason why they considered the mentioned diagnoses as problematic. These open-ended explanations showed considerable variability in terms of content and level of detail provided. Through inductive content-analysis categorization, four major themes were identified for why a diagnosis was considered problematic: 1) Validity, where the diagnosis or the diagnostic requirements do not have adequate specificity or scientific foundation as they are currently formulated (e.g., “the criteria are too broad and the differences among patients with that diagnosis too big”); 2) Assessment, which includes dissatisfaction with the methods for evaluating diagnostic criteria, symptomatology, and severity (e.g., “a continuum based on severity would be better and more significant”); 3) Applicability, where important features of specific populations (e.g., based on gender, cultural background, or age) are not acknowledged by the diagnostic requirements (e.g., “this diagnosis is poorly fit into aged clinical population”); and 4) Exclusion, where the actual diagnostic requirements omit symptoms or areas relevant to the diagnosis (e.g., “neurocognitive deficits are an important aspect and so are social cognitive deficits but they are not included in the current diagnostic criteria”).

Validity was the main reason provided by psychologists (n=274, 75.3%) and psychiatrists (n=188, 41.9%) for why they considered any particular diagnosis to be problematic. The second and third most common reasons were related to Applicability (psychiatrists n=100, 22.3%; psychologists n=34, 9.3%) and Assessment (psychiatrists n=82, 18.3%; psychologists n=34, 9.3%). Psychiatrists (n=79, 17.6%) and psychologists (n=22, 6%) referred to Exclusion least often (χ2 (3)=92.6, p<.001). The percentage of responses for diagnostic categories most frequently identified as problematic for reasons of validity are presented in Table 3, along with prototypical examples of participants’ views that reference poor validity. For the general category of “all diagnoses,” the most common rationales related to Exclusion (n=23, 48.9%; e.g., “not so clear, from a clinical point of view insufficient description”).

Frequency and examples of rationales related to validity provided by clinicians for regarding specific diagnoses as problematic.

| Diagnoses | n | % | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pervasive developmental disorders | 22 | 61.1 | “Developmental disorders are described with symptoms seen only in children -this is a problem, when the patients aren’t diagnosed until they’re grown up”. |

| Asperger's syndrome | 33 | 73.3 | “It is often clinically difficult to differentiate from high functioning autism. The differentiation based on language development itself is not really meaningfully enough”. |

| Personality Disorders | 79 | 55.2 | “They seem to have the same criteria and mostly get superimposed with other diagnosis”. |

| Attention Decifit-Hyperactivity Disorder | 5 | 48.4 | “Diagnosis is too inclusive and it can be very difficult to differentiate it from other diagnoses due to too much overlap in symptoms”. |

| Schizophrenia | 36 | 59.0 | “Diagnostic criteria must be simpler and straight forward not like a discussion with various probabilities”. |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 30 | 76.9 | “The distinction between mood congruent/incongruent symptoms is artificial”. |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 50 | 60.2 | “I find it can be difficult to use this diagnosis confidently as there is so much overlap with other conditions, particularly in those with a history of abuse”. |

| Borderline personality disorder | 29 | 67.4 | “Difficult and very pejorative diagnosis and at least some people who fit into this could have a diagnosis of complex PTSD or some other diagnosis for significant effects on personality”. |

| Depression | 18 | 37.5 | “Depressions and their validity, their functional effects, the legal problems they cause in the term of incapacity to work. There is no practical correlation between “clinic” subjective dysfunctions and ‘objective’ effects”. |

| Bipolar disorder | 33 | 70.2 | “Bipolar disorder, I have noticed it can be given to almost anyone. Very indefinite criteria”. |

| Dissociative disorders | 29 | 74.4 | “Dissociative disorders need not be given a special diagnostic category, it is associated with many severe psychopathologies”. |

| Adjustment disorders | 22 | 78.6 | “It is clinically vague and difficult to take cultural pathoplastic effects in consideration”. |

| Somatoform disorders | 18 | 58.1 | “Not clearly defined, difficult to use, not clearly delineated”. |

When results were compared by geographical region, personality disorders were the diagnoses most reported as problematic in Europe (n=160, 22%), Asia (n=39, 23.4%) and Eastern Mediterranean (n=8, 18.2%). For Latin America and Africa, the report of all diagnoses as problematic was the most frequent (n=27, 24.8% and n=16, 36.4%, respectively), while bipolar disorder was the most cited diagnosis by participants in North America (n=19, 20%).

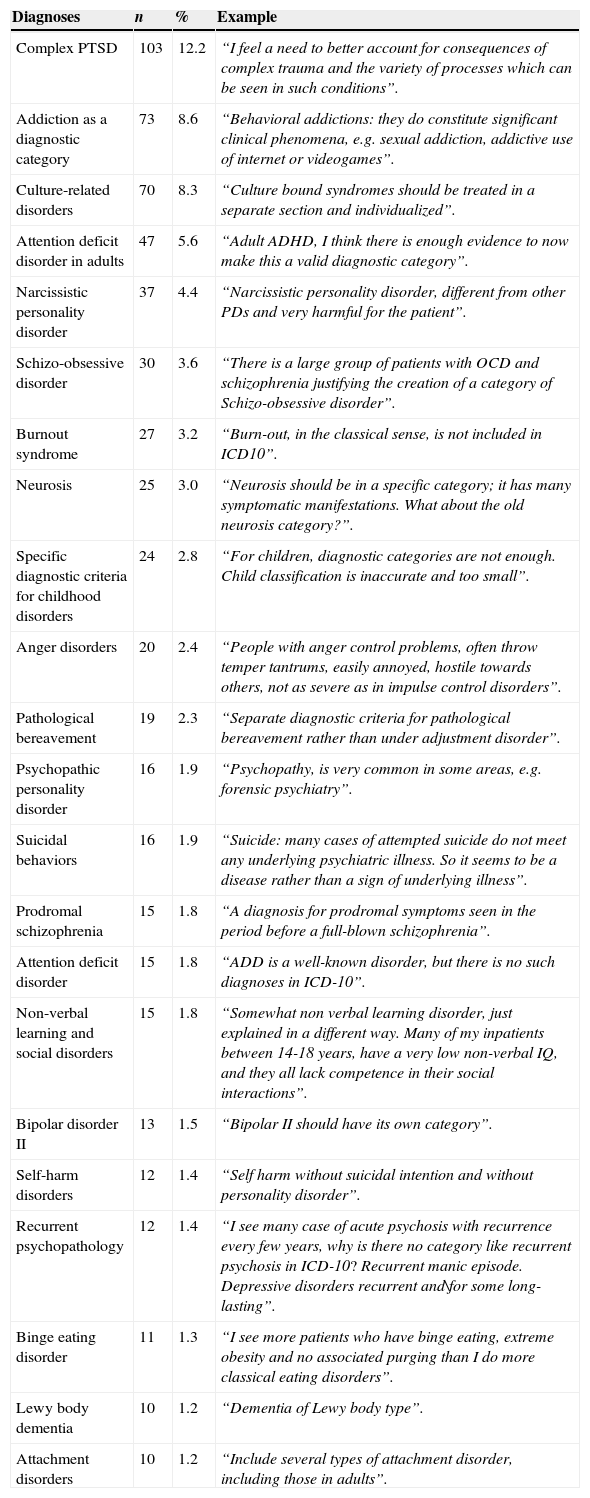

Diagnostic categories that should be added to diagnostic classificationsThe “yes/no” item for this question was presented to all participants and 95.4% (n=3074) responded to it; 978 (31.8%) gave a “yes” response, indicating that additional diagnostic categories should be added to the classification. Of those who responded “yes,” 237 (26%) did not specify the diagnoses to be included or gave answers that were unclear or not related to the initial question (e.g., “of course we need these, that is why we sometimes diagnose patient as not otherwise specified”; “sometimes the clinical symptoms do not match criteria so it is not possible to label patient as mentally ill”). Thus, a total of 85 diagnoses that were reported by 741 respondents. Diagnoses that were suggested more than 10 times are shown in Table 4.

Diagnoses participants indicated should be added to current classifications of mental disorders, with example rationales.

| Diagnoses | n | % | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complex PTSD | 103 | 12.2 | “I feel a need to better account for consequences of complex trauma and the variety of processes which can be seen in such conditions”. |

| Addiction as a diagnostic category | 73 | 8.6 | “Behavioral addictions: they do constitute significant clinical phenomena, e.g. sexual addiction, addictive use of internet or videogames”. |

| Culture-related disorders | 70 | 8.3 | “Culture bound syndromes should be treated in a separate section and individualized”. |

| Attention deficit disorder in adults | 47 | 5.6 | “Adult ADHD, I think there is enough evidence to now make this a valid diagnostic category”. |

| Narcissistic personality disorder | 37 | 4.4 | “Narcissistic personality disorder, different from other PDs and very harmful for the patient”. |

| Schizo-obsessive disorder | 30 | 3.6 | “There is a large group of patients with OCD and schizophrenia justifying the creation of a category of Schizo-obsessive disorder”. |

| Burnout syndrome | 27 | 3.2 | “Burn-out, in the classical sense, is not included in ICD10”. |

| Neurosis | 25 | 3.0 | “Neurosis should be in a specific category; it has many symptomatic manifestations. What about the old neurosis category?”. |

| Specific diagnostic criteria for childhood disorders | 24 | 2.8 | “For children, diagnostic categories are not enough. Child classification is inaccurate and too small”. |

| Anger disorders | 20 | 2.4 | “People with anger control problems, often throw temper tantrums, easily annoyed, hostile towards others, not as severe as in impulse control disorders”. |

| Pathological bereavement | 19 | 2.3 | “Separate diagnostic criteria for pathological bereavement rather than under adjustment disorder”. |

| Psychopathic personality disorder | 16 | 1.9 | “Psychopathy, is very common in some areas, e.g. forensic psychiatry”. |

| Suicidal behaviors | 16 | 1.9 | “Suicide: many cases of attempted suicide do not meet any underlying psychiatric illness. So it seems to be a disease rather than a sign of underlying illness”. |

| Prodromal schizophrenia | 15 | 1.8 | “A diagnosis for prodromal symptoms seen in the period before a full-blown schizophrenia”. |

| Attention deficit disorder | 15 | 1.8 | “ADD is a well-known disorder, but there is no such diagnoses in ICD-10”. |

| Non-verbal learning and social disorders | 15 | 1.8 | “Somewhat non verbal learning disorder, just explained in a different way. Many of my inpatients between 14-18 years, have a very low non-verbal IQ, and they all lack competence in their social interactions”. |

| Bipolar disorder II | 13 | 1.5 | “Bipolar II should have its own category”. |

| Self-harm disorders | 12 | 1.4 | “Self harm without suicidal intention and without personality disorder”. |

| Recurrent psychopathology | 12 | 1.4 | “I see many case of acute psychosis with recurrence every few years, why is there no category like recurrent psychosis in ICD-10? Recurrent manic episode. Depressive disorders recurrent and\for some long-lasting”. |

| Binge eating disorder | 11 | 1.3 | “I see more patients who have binge eating, extreme obesity and no associated purging than I do more classical eating disorders”. |

| Lewy body dementia | 10 | 1.2 | “Dementia of Lewy body type”. |

| Attachment disorders | 10 | 1.2 | “Include several types of attachment disorder, including those in adults”. |

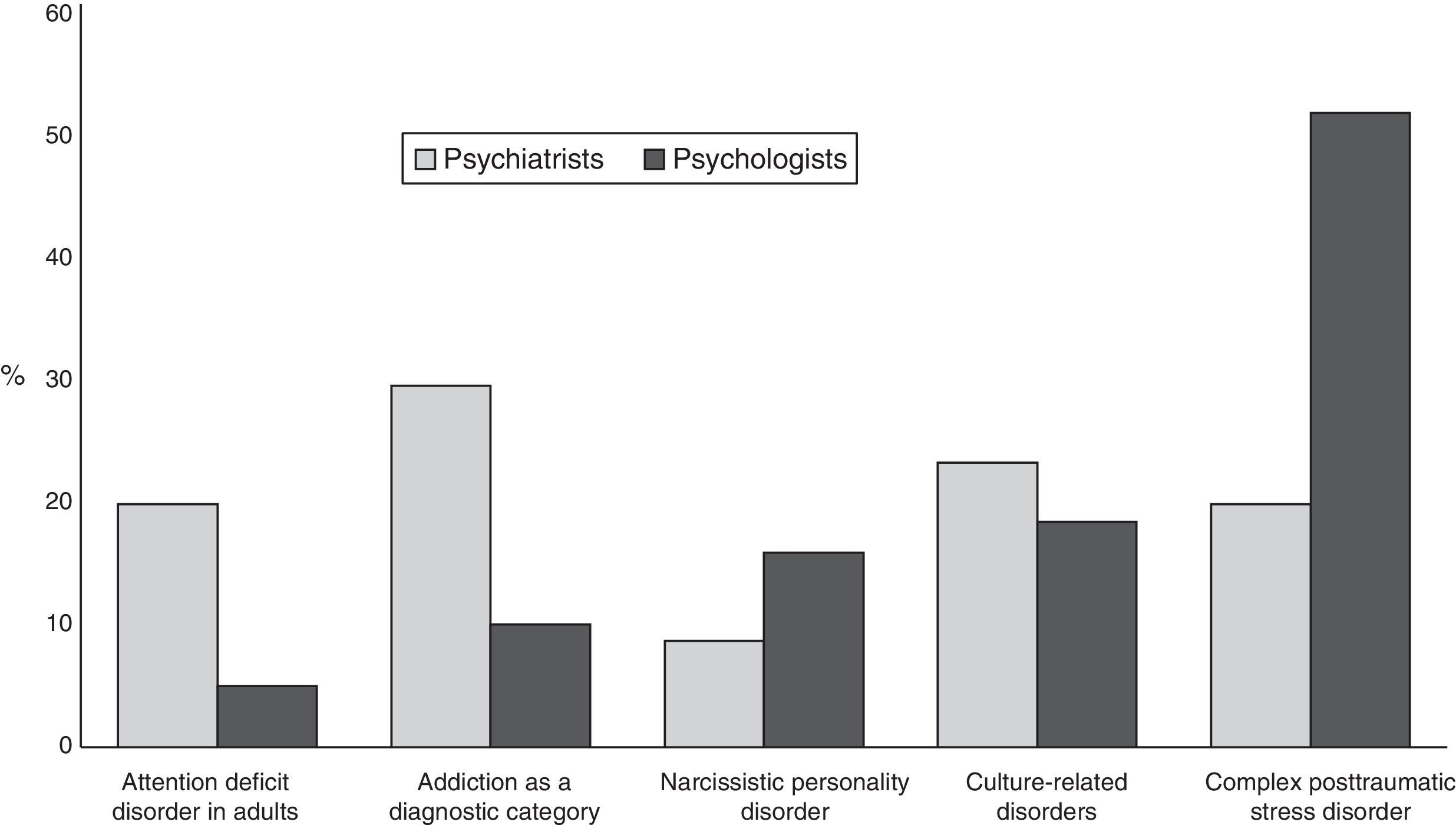

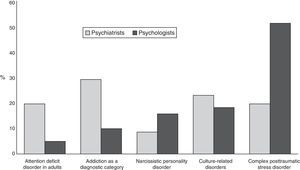

Frequencies for the most commonly mentioned diagnoses (by≥4% of the total sample, 330 total reports) were compared between psychiatrists and psychologists (Figure 2). Psychiatrists and psychologists recommended the inclusion of culture-related disorders at similar rates. Compared to psychologists, a higher percentage of psychiatrists suggested the addition of addiction as a specific diagnosis, attention deficit disorder in adults and culture-related disorders. On the other hand, more psychologists reported the need to include complex post-traumatic stress disorder and narcissistic personality disorder when compared to psychiatrists (χ2 (4)=53.2, p<.001).

Culture-related disorders and addiction as a specific diagnostic category were the two most frequently cited diagnoses to be added by participants from Latin America (n=17, 45.9% and n=14, 37.8%, respectively), Asia (n=26, 37.1% and n=31, 45.6%, respectively) and the Eastern Mediterranean (n=5, 45.1% each one). Among participants from Europe (n=82, 44.1%), Africa (n=6, 40%) and North America (n=7, 53.8%), complex post-traumatic stress disorder was the most frequently suggested diagnosis to be included in classification systems.

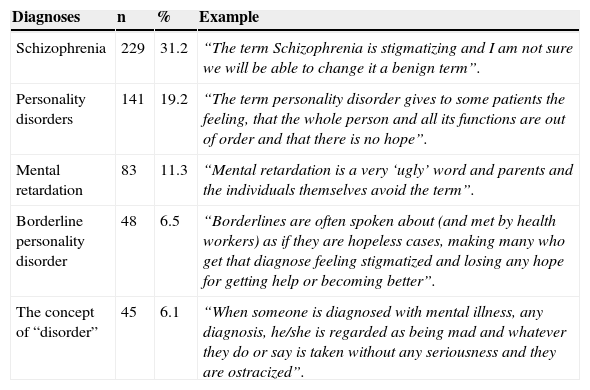

Perceived stigmatizing diagnosesThe “yes/no” item for this question was answered by 3115 (96.7%) of the participants. Of these, 27.2% (n=848) responded “yes,” indicating that the diagnostic system they used contained stigmatizing terminology. One-hundred and twelve answers were not included in the subsequent content analysis of this item as respondents gave nonspecific responses (e.g., “there are many examples; the medical context makes the person irrelevant and parts of body relevant; of course but that cannot preclude their use in a clinical setting. Any new term will become stigmatized if it refers to an unfavorable state”). A total of 42 specific diagnoses were described as stigmatizing. Diagnoses mentioned by more than five percent of the total sample are presented in Table 5. These diagnoses account for 74.3% of the total positive observations for this item.

Diagnoses most frequently reported as stigmatizing diagnoses by clinicians, with example rationales.

| Diagnoses | n | % | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia | 229 | 31.2 | “The term Schizophrenia is stigmatizing and I am not sure we will be able to change it a benign term”. |

| Personality disorders | 141 | 19.2 | “The term personality disorder gives to some patients the feeling, that the whole person and all its functions are out of order and that there is no hope”. |

| Mental retardation | 83 | 11.3 | “Mental retardation is a very ‘ugly’ word and parents and the individuals themselves avoid the term”. |

| Borderline personality disorder | 48 | 6.5 | “Borderlines are often spoken about (and met by health workers) as if they are hopeless cases, making many who get that diagnose feeling stigmatized and losing any hope for getting help or becoming better”. |

| The concept of “disorder” | 45 | 6.1 | “When someone is diagnosed with mental illness, any diagnosis, he/she is regarded as being mad and whatever they do or say is taken without any seriousness and they are ostracized”. |

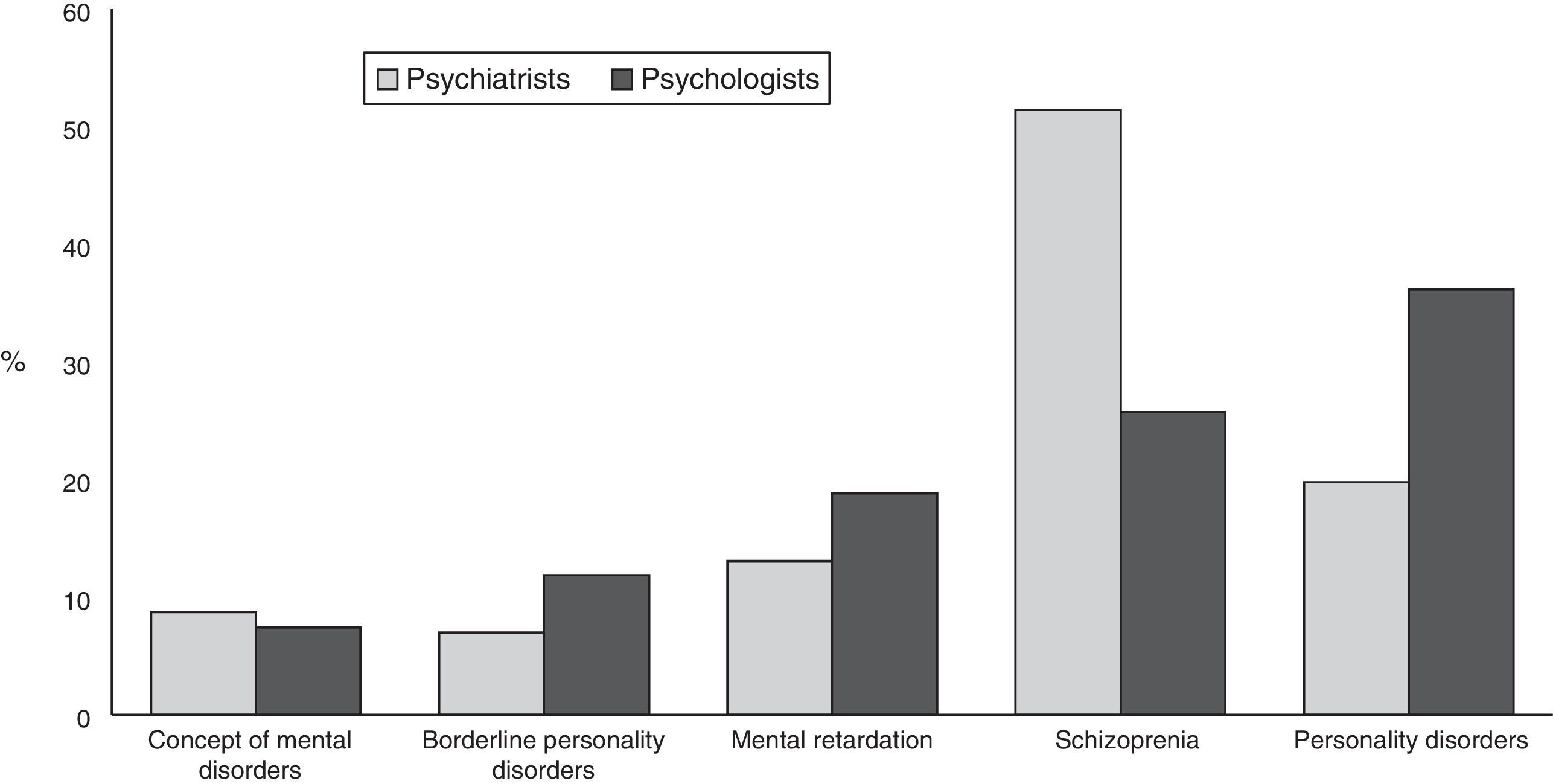

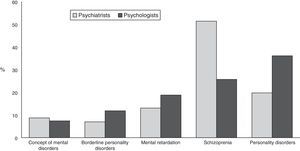

The most frequently reported stigmatizing diagnoses were compared by profession (Figure 3). Psychiatrists were more likely to view schizophrenia as a stigmatizing diagnosis, while a higher percentage of psychologists viewed personality disorders as stigmatizing, particularly borderline personality disorder (χ2 (4)=39.7, p<.001).

Reasons for stigmatization were given for only 24.7% (n=135) of the 546 reported instances of the most frequently reported stigmatizing diagnoses. Coding of the open-ended explanations for this item indicated four primary reasons that particular diagnoses were considered stigmatizing: 1) Lack of understanding or knowledge about the diagnosis among the general population (e.g., “most people don’t understand that schizophrenia doesn’t mean a total catastrophe for your life”; “are all words commonly used by non-professionals that make them have other meanings among common people”); 2) Negative meaning, where the diagnosis or diagnostic requirements are generally viewed as offensive, derogatory, or having other nonspecific negative associations (e.g., “the term gives the impression that the very essence of the persons being is wrong and pathologic”; “diagnosis is culturally pejorative”); 3) Violence, where the diagnosis is perceived to be associated with aggression, dangerousness and violent behavior (e.g., “schizophrenia is often connected to violence”; “understood in popular culture as describing multiple personality disorder of the Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde kind”); and 4) Translation and cultural aspects, including instances where the adaptation of definitions to other languages and cultural settings leads to stigmatizing terms for specific societies (e.g., “in Chinese it means ‘Mad’ or ‘Loss of Mind’; “translation of the terms sounds awkward in our culture”).

Schizophrenia was considered stigmatizing because of public lack of understanding of the condition (n=27, 42.9%; e.g., “I think the term ‘schizophrenia’ often is misunderstood be the larger public, for instance media, and in ways that may harm patients and create fear among common people”), as well as the public perception of its being linked to violence (n=8, 12.7%; e.g., “schizophrenia is often connected to violence”). The main reasons that specific personality disorders were considered stigmatizing related to negative connotations of the diagnoses (n=29, 74.4%; e.g., “all the personality disorders are used in a derogatory way”) followed by difficulties in translation and cultural aspects (n=8, 20.5%; e.g., “personality disorder/personlighetsforstyrrelse (Norwegian) refers to something very personal, as if the person is bad/wrong/broken”). For borderline personality disorder, negative connotations (e.g., “most of the borderline personality disorders description is far to judgmental and negative in wording”) and lack of understanding (e.g., “borderlines are often spoken about as if they are hopeless cases, making many who receive that diagnose feel stigmatized and lose any hope for getting help or becoming better”) were the main reasons cited for stigmatization (n=7, 63.6% and n=4, 36.4%, respectively). For mental retardation, negative connotations (n=11, 73.3%; e.g., “mental retardation makes people think of human vegetables”), difficulties in translation and cultural factors (n=2, 13.3%; e.g., “mental retardation - in Norwegian: psykisk utviklingshemming - is indeed a stigmatizing term”) and lack of understanding (n=2, 13.3%; e.g., “often people use this term disparagingly, calling someone a retard”) were the reasons described for stigmatization. Finally, for mental disorders in general, both negative connotations (n=5, 71.4%; e.g., “the word ‘mental’ itself is popularly believed to mean a typical disorganized person found on the streets and the same meaning is attached by public to all psychiatric symptoms and to the field of psychiatry”; “most terms are regarded as offensive”) and difficulties in translation and cultural factors (n=2, 28.6%; e.g., “the concept of ‘disorder’ is difficult to separate from cultural differences”) were the reasons cited for their being viewed as stigmatizing.

Schizophrenia was the most frequently identified stigmatizing diagnoses by participants in Asia (n=32, 54.2%), the Eastern Mediterranean region (n=14, 53.8%), Europe (n=151, 41%) and Latin America (n=25, 46.3%). Mental retardation was the most frequently identified stigmatizing diagnosis by participants in Africa (n=6, 42.9%) and borderline personality disorder in North America (n=11, 44%).

Need for a national classificationNinety-seven percent of the participants (n=3,053) answered the “yes/no” item. Of these, 14.4% of participants (n=441) responded “yes” to this item, indicating a need for a national diagnostic classification system that is more than just a translation of the ICD.

A total of 324 (73.4%) of the participants provided specific explanations for their affirmation of the need for a national classification system. The main reasons were: 1) the classification needs to consider cultural and socio-historical differences of societies (n=194, 59.9%; e.g., “we have a unique culture and experience, so we need our own classification system”, “nations and cultures require diagnostic criteria that address the human in the context of culture”); 2) there is a different perception of what is and what is not pathological by country (n=56, 17.3%; e.g., “in some societies it is considered normal to fear witchcraft”; “the presentation of psychotic symptoms in a person may be viewed from a cultural perspective as a transition state to becoming a ‘traditional healer”’); 3) the inclusion of an additional national diagnostic system that would complement (rather than replace) current classifications (n=56, 17.3%; e.g., “may be some sort of complementary classification considering culture and language”; “perhaps adding extra criteria - relevant to our society - that would aid in making diagnoses”); and 4) to emphasize the national adaptation as a way to avoid using foreign classifications (n=18, 5.6%; e.g., “it is difficult to identify true etiologies when using foreign classifications”; “it is better to describe the reality with your own language”). Significant professional differences were found for two of the response categories: the third reason (national supplement for general classifications) was more frequently reported by psychiatrists than psychologists (21.2% vs. 10.7% respectively; χ2 (1)=5.77, p=.01), while the fourth reason (national adaptation to avoid using foreign classifications) was more frequently reported by psychologists than psychiatrists (9.9% vs. 3.0%; χ2 (1)=7.0, p=.008).

There were regional differences in the proportion of participants who identified a need for a national classification. US psychologists and European psychiatrists and psychologists were least likely to endorse the need for a national classification (5.8% and 4.4%, respectively), followed by the Eastern Mediterranean. Higher proportions of psychiatrists and psychologists from the Asian (23.9%), African (33.3%) and Latin American (33.7%) regions endorsed the need for a national classification.

DiscussionThe present study constitutes part of an effort by WHO directed towards understanding mental health clinicians’ perceptions of the needs for changes in mental disorder classification in order to inform the development of the ICD-11, in which the improving the clinical utility of the classification has been identified as a particular goal.

Problematic, missing and stigmatizing diagnosesThe most problematic diagnostic group was specific personality disorders, especially among psychiatrists. Clinicians generally cited poor validity and a lack of specificity as their reasons for finding these categories to be inadequate. Nevertheless, the classification of personality disorders that has been included in DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) is unchanged from that in DSM-IV, though a very complicated dimensional alternative system was also included in an appendix. Findings suggest that, in order to improve clinical utility of the forthcoming ICD-11, a major revision of the guidelines for personality disorders should be undertaken, perhaps focusing on differential characteristics or a different conceptual system to reduce overlap among disorders. In fact, a major revision and simplification of the classification of personality disorders has been proposed for ICD-11 (Tyrer, Crawford, & Mulder, 2011), consistent with these findings. These data also suggest a need for training efforts related to this area of the ICD-11.

Complex post-traumatic stress disorder was the most frequent diagnosis suggested for inclusion in the classification of mental disorders, especially by psychologists. Participants reported that the diagnostic system needed to better account for the consequences of complex trauma and the differentiated processes that can arise when people experience extreme or prolonged traumatic stressful events from which escape is difficult or impossible. This is consistent with proposals for disorders specifically related to stress in ICD-11 (Maercker et al., 2013), which include the addition of complex post-traumatic stress disorder, characterized by the core symptoms of PTSD as well as difficulties in emotion regulation, beliefs about oneself as diminished, defeated or worthless, and difficulties in sustaining relationships. This category was not added to the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Some other categories recommended for inclusion by clinicians are already a part of the proposed content of ICD-11. These include bipolar type II disorder (Strakowski, 2012) and Binge eating disorder (Al-Adawi et al., 2013), both of which are also in DSM-5, as well as prolonged grief disorder (Maercker et al., 2013), none of which were included in DSM-5. Lewy body dementia is proposed for inclusion in the chapter on Diseases of the Nervous System. Other suggests reflect some lack of clarity about the contents of ICD-10. Attention deficit disorder is called hyperkinetic disorder in ICD-10, and diagnosis in adults is specifically permitted, though a key characteristic of the disorder is its early onset. Proposals for ICD-11 include changing the name of these disorders to attention deficit disorders. The proposed revision for ICD-11 also permits their diagnosis in adults, though continues to describe them as characterized by onset in early life (childhood or adolescence). Unlike DSM-5, proposals for ICD-11 include a category of attention deficit disorder without hyperactivity. Some of the other categories recommended by clinicians were considered by ICD-11 Working Groups but not recommended for inclusion in ICD-11. A complete list of categories proposed for inclusion in ICD-11 can accessed at http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd11/browse/l-m/en, and will be modified based on an extensive review and comment process and the results of field studies.

In terms of diagnoses that clinicians considered to be stigmatizing, as was hypothesized and in line with previous research (Nunnally, 1961; Pescosolido et al., 1999), schizophrenia was the diagnosis most frequently identified, mainly due to lack of public understanding or knowledge about the diagnosis. Further contributing to the stigma, the diagnostic term is used inaccurately in common language within the general population and is often (incorrectly) associated with aggression, dangerousness, and violent behavior. In response to these factors, the Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology decided to change the Japanese term for schizophrenia from “seishin bunretsu byo” (“mind-split-disease”) to “togo shitcho sho” (“integration disorder”), in an effort to reduce the stigma related to schizophrenia and to improve clinical practice in the management of the disorder (Sato, 2006).

Indeed, proposed modifications in the names of specific stigmatized diagnoses as a part of the development of ICD-11 involve complex and sensitive social issues (e.g., Drescher, Cohen-Kettenis, & Winter, 2012). Also, participants in the present study reported problems regarding the translation of terms to other languages and cultural settings were reported. According to clinicians, translation issues could lead to stigmatizing terms for specific societies. Better translation of diagnostic terminology into different languages may help to support WHO's goal of reducing the stigma of mental disorders in order to increase access to care (World Health Organization, 2012).

Cultural issuesAn overwhelming majority (85.6%) of both psychiatrists and psychologists reported that there is no need for a national classification. Nevertheless, those who perceived a need for a national system stated that the mental disorder classification should consider cultural and socio-historical diversity in the expression of psychopathology, differences in the perception of what is and what is not pathological in different countries, and the existence of syndromes specifically linked to culture. A large majority (67%) of those professionals who advocated for national classification were from Africa or Latin America.

All proposals for Mental and Behavioural Disorders in ICD-11 have been developed by international and multidisciplinary Working Groups, which include members from all WHO global regions and a high percentage of members from low- and middle-income countries. Moreover, WHO is making a major effort to field test all proposals globally. Internet-based field testing is being conducted through the Global Clinical Practice Network (GCPN), an global network of approximately 10,000 clinicians from more than 100 countries who have agreed to participate in field studies for the ICD-11. Registration to participate in the GCPN is open to all mental health and primary care professionals who are authorized to practice in their countries and is available in nine languages: Arabic, Chinese, English, French, German, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, and Spanish. Field testing of all proposals for ICD-11 is being conducted internationally and in multiple languages. (To register for the GCPN, go to http://www.globalclinicalpractice.net.) The development and field testing of all ICD proposals are therefore international, multilingual, and multidisciplinary. This process is intended to improve the clinical utility and global applicability of the resulting classification, and therefore reduce the need for national adaptations. This would enhance the comparability of data from around the world. Moreover, important and empirically-supported variations in disorder presentation will be described as a specific part of the diagnostic guidance to be provided for ICD-11 Mental and Behavioural Disorders. After the material for the core classification has been developed, a separate examination will be conducted to determine the need for additional categories that are specific to particular cultural contexts.

Study limitations and additional research needsThe specificity of the sample and the non-probabilistic method for recruiting participants suggests some that a degree of caution in generalizing the results is warranted, even to all English- and Spanish-speaking psychiatrists and psychologists. Thus, the present findings should not be interpreted as representing all clinicians or all countries, but rather as providing suggestions and rationales based on a very large sample of English- and Spanish-speaking psychiatrists and psychologists in diverse contexts in 35 countries. Another limitation is that it was not possible for the purposes of the present study to examined open-ended responses in the languages other than English and Spanish in which the original surveys were administered: a total of 17 additional languages for the WHO-WPA survey, and three additional languages for the WHO-IUPsyS survey, limiting the global richness of the present analysis.

Moreover, the open-ended responses that were analyzed in the present study were in response to structured “yes/no” questions that focused on specific issues. If psychologists and psychiatrists had been asked in a more open-ended way about what aspects of current classification systems they found problematic or how they thought that classification systems could be improved, a variety of other themes would likely have emerged. Some of these issues, such as the importance of incorporating a dimensional perspective and role of functional impairment in diagnosis, were the focus of closed-ended questions in the original surveys (see Evans et al., 2012; Reed et al., 2011), but were not follow up with open-ended questions. A more systematic examination of clinicians’ open-ended suggestions for how classification systems might be improved would clearly be possible. Such studies could also address the aspects of existing classifications that clinicians find helpful and satisfactory, as a way to gain additional insight into what kinds of descriptors, heuristics, or content should be included in potential diagnostic categories.

Another important area for further research would be more systematic assessments of the experiences of health care providers who are not mental health specialists. WHO (2012) has indicated that the develop the capacity of these professionals to identify individuals who need mental health services and to provide basic treatment will be a critical aspect of addressing the global gap between treatment needs and available services, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

ConclusionsThese findings of this study describe a number of significant challenges to be addressed in order to introduce ICD-11 in the diverse global regions represented in this study. These results also underscore the utility and importance of international surveys of clinicians within the challenging context of global mental health care. Further research of this kind is necessary in order to develop a genuinely global diagnostic classification system for mental and behavioural disorders.

The World Health Organization Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse has received direct support that contributed to the conduct of this study from several sources: The International Union of Psychological Science, the National Institute of Mental Health (USA), the World Psychiatric Association, the Spanish Foundation of Psychiatry and Mental Health (Spain), and the Santander Bank UAM/UNAM endowed Chair for Psychiatry (Spain/Mexico). Further thanks are due to Dr. Jared Keeley for his very helpful comments on earlier versions of this article.

In the WHO-WPA Survey (Reed et al., 2011), the questions about problematic categories and categories that should be added were asked specifically in relation to the ICD-10 (e.g., “Are there diagnostic categories in ICD-10 with which you are especially dissatisfied, or that you believe are especially problematic in terms of their goodness of fit in clinical settings?”). Because it was assumed that most US psychiatrists would not be sufficiently familiar with the ICD-10 to be able to answer these questions in relation to that classification system, these questions were made more generic, such that they did not refer explicitly to the ICD-10, in the version of the survey that was used for members of the American Psychiatric Association (e.g., “Are there diagnostic categories with which you are especially dissatisfied, or that you believe are especially problematic in terms of their goodness of fit in clinical settings?”). The question on the need for a national classification was not asked of members American Psychiatric Associations (Reed et al., 2011). This was because even though they were using what is technically a national classification (the DSM-IV), they were unlikely to be aware of the relationship of the DSM-IV to the ICD and therefore this question would be difficult to understand. In the subsequent WHO-IUPsyS survey (Evans et al., 2013), the more generic versions of the questions about problematic categories and categories that should be added, as well as the question on the need for a national classification, were administered to members of all participating national psychological associations. For the present analysis, data from the ICD-specific versions of the questions on problematic categories and categories that should be added were combined with data from the more generic versions.

R. Robles, A. Lovell, M. Medina-Mora, and M. Maj are members of the WHO International Advisory Group for the Revision of ICD-10 Mental and Behavioural Disorders and/or of Working Groups that report to the International Advisory Group. G. Reed is a member of the WHO Secretariat, Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, WHO. Unless specifically stated, the views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the official policies or positions of the International Advisory Group or of WHO.

Available online 5 May 2014