This instrumental study examines the psychometric properties of the Psychological Dating Violence Questionnaire (PDV-Q). The scale was developed with the aim of evaluating subtle and overt psychological abuse among dating couples, and its possible bi-directionality in the implication as victim and as aggressor. A sample group of 670 heterosexual university students (62.8% women), aged between 19 and 25 years old (M = 22; SD=1.78), took part in the study. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis revealed a satisfactory index of reliability with two different scales: Victimization and Aggression. The external validity was checked with a physical violence measure (modified Conflict Tactic Scale-2). The results indicated a significant but low correlation between psychological and physical scales. The PDV-Q joins dating and intimate violence instruments potentialities and tries to overcome their limitations. It includes a wide range of violent behaviours and it is adapted to specific characteristics from young couples.

Este estudio instrumental presenta las propiedades psicométricas del Cuestionario de Violencia Psicológica en el Cortejo (PDV-Q). El cuestionario se diseñó con el objetivo de evaluar el abuso psicológico sutil y manifiesto presente en parejas de jóvenes universitarios y su posible bidireccionalidad en la implicación como víctima y como agresor. Se contó con una muestra de 670 estudiantes universitarios heterosexuales (62,8% mujeres), con edades comprendidas entre los 19 y 25 años (M=22; DT=1,78). Los análisis exploratorios y confirmatorios mostraron índices de fiabilidad satisfactorios con dos escalas, Victimización y Agresión. La validez externa fue evaluada con la violencia psicológica, medida a través de una versión modificada del Conflict Tactic Scale-2. Los resultados mostraron correlaciones significativas, aunque bajas, entre las escalas de violencia psicológica y física. El PDV-Q aúna las potencialidades de los instrumentos de cortejo y los de violencia en la pareja marital, salvando las principales dificultades recogidas. Incluye un amplio rango de comportamientos violentos, adaptándolos a las características concretas de las parejas jóvenes.

Over the last few decades national and international studies about romantic relationships have gained strength, such relationships are considerably serious outside marriage or cohabitation. Adolescents and young relationships, which are prior to the consolidation of the couple and outside marriage or cohabitation -known as dating- (Connolly & McIsaac, 2011), tend to be different from those held by adults in areas such as level of commitment, duration, sexual intimacy and the way to solve conflicts (Furman & Wehner, 1997; Molidor & Tolman, 1998). Thus, the violent dynamic that might arise will have different characteristics (for example, there's no financial dependence, emotional blackmail or other abusive conducts in relation to children, or household co-responsibility, etc.). The Report of Youth in Spain (INJUVE, 2012) points out that only 23.8% of young people between 20 to 24 years of age live with their partners and it is also observed that the higher the educational level the higher the percentage of youngsters living at the parental home. All these features make the relationships and violent manifestations among young university couples quite different from the adult ones. Violence in dating relationships in young people are characterized for being moderate, bidirectional and reciprocal (Nocentini, Pastorelli, & Menesini, 2011; Ortega & Sánchez, 2010; Viejo, 2014).

Notwithstanding, there has been less research on psychological violence than on other types of maltreatment, like physical or sexual abuse. Perhaps, the lack of psychological violence centered research is due to the fact that it can be less objective and more difficult to evaluate than physical maltreatment and other types of violence (Calvete, Corral, & Estévez, 2005; Rodríguez-Carballeira et al., 2005).

It has been in the last few decades when research interest has emerged in this field regarding adolescent and young couples’ relationships. The majority of studies that include this or any other type of violence in dating relationships have considered it as a risk factor of violence in the adulthood or marital couples (Gormley & López, 2010; Moreno-Manso, Blázquez-Alonso, García-Baamonde, Guerrero-Barona, & Pozueco-Romero, 2014), establishing that psychological partner violence is a behaviour repeated along the following relationships (Lohman, Neppl, Senia, & Schofield, 2013).

Scientific literature has established that psychological violence is defined by attitudes, behaviours and styles of communication based on humiliation, control, disapproval, hostility, denigration, domination, intimidation, threat of direct violence and jealousy (Murphy & Hoover, 1999; O’Leary & Smith-Slep, 2003). O’Leary (1999) identified in his definition control and domination actions but also verbal aggression including denigration and recurring criticism towards the partner. Marshall (1999) introduced a new perspective in the study of psychological violence by differencing overt and subtle ways of abuse. Overt psychological violence is characterized by spreading behaviors of control and dominance easy to recognize because an aggressive and dominant style is used and it clearly affects resulting feelings, including: domination, indifference, monitoring and discredit. This type of abuse tends to occur in situations of conflict. Nonetheless, subtle psychological violence can appear in loving, joking and caring situations. Messages and actions to undermine, discount and isolate the partner are defined as subtle. These forms are independent from domination and produce an emotional damage that is difficult to recognize as abusive.

International and national research on psychological violence has shown higher rates of prevalence than other types of intimate violence (Liles et al., 2012; Zorrilla et al., 2010). These higher rates of psychological violence have been identified in dating relationships in which the implication is around 80%. Percentages regarding victimization range between 76-87% among boys and 78-82% among girls, and regarding aggression between 74-85% among boys and 83-90% among girls (Cortés-Ayala et al., 2014; Hines & Saudino, 2003; Straus, 2004; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). In a recent study with university students about psychological abuse, different types of behaviors were observed to define this phenomenon, such as disparagement, hostility, indifference, intimidation, imposition of behavioral patterns, blaming and apparent kindness; the results pointed out that the indifference was the most common form of psychological violence in dating (Blázquez-Alonso, Moreno-Manso, & García-Baamonde, 2012). Different studies have found gender differences in psychological violence. On one hand, females perpetrate significantly more psychological aggression than males (Hines & Saudino, 2003). On the other hand, many studies and social opinion supported by media establish a wider presence of psychological abuse manifestations with the highest evidence of a greater rate of patterns among men (Moreno-Manso et al., 2014).

It is widely recognized that psychological violence is fairly stable and has a severe impact (Carney & Barner, 2012; Shortt et al., 2012). Marshall (1999) recognized that subtle and overt acts of psychological abuse are likely to harm self-perception, well-being and the perception of the relationship and the partner. Research has shown that psychological and physical violence are interrelated, actually psychological violence could precede physical one (Muñoz-Rivas, Graña, O’Leary, & González, 2007; Straus et al., 1996).

The most recognized instruments about psychological abuse in dating relationships are The Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationship Inventory (CADRI) (Wolfe et al., 2001), validated with Spanish sample (Fernández-Fuertes, Fuertes, & Pulido, 2006); and the Modified Conflict Tactics Scale (M-CTS) (Neidig, 1986). Both scales consider whether the person had suffered or perpetrated different violent behaviors. M-CTS and CADRI included psychological violence as a short subsection into the dating violence questionnaire, dismissing the individual nature of the phenomenon. The M-CTS has been criticized because it does not include restrictive behaviors and public humiliation (Calvete et al., 2005).

Due to these limitations some studies have decided to use measures which had been designed for adult population. There is a wide range of instruments designed to measure psychological violence from a women maltreatment perspective in adulthood, as the Inventory of Psychological Abuse in the Context of Couple Relationships (Calvete et al., 2005), The Index of Spouse Abuse (Hudson & McIntosh, 1981) and The Spanish Version of the Index of Spouse Abuse (Sierra, Monge, Santos-Iglesias, Bermúdez, & Salinas, 2011). The Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory (PMWI) (Tolman, 2001) is one of the most used scales to evaluate abuse against women; it has two subscales called domination-isolation and emotional-verbal aggression. The Scale of Emotional Abuse (Murphy & Hoover, 1999) offers four subscales: Domination-intimidation, Restrictive isolation, Denigration and Hostile withdrawal and The Profile of Psychological Abuse (Sacket & Saunders, 1999) is composed of four victimization factors referred to ridicule traits, criticize behaviours, to ignore the partner and control-jealousy. Marshall created the Subtle and Overt Psychological Abuse of Woman Scale (SOPAS). The psychometrics properties of this scale were presented by Jones, Davidson, Bogat, Levendosky and Von Eye (2005); and Buesa and Calvete (2011) adapted this scale to Spanish population finding that violence against women by an intimate partner can take many modalities, including forms of overt and subtle victimization in only one factor.

Nevertheless, most of these instruments have a gender bias -male violence against women-, considering only women or women victims of domestic violence perspectives. Therefore its generalization is questioned in social areas in which some domesticity elements are not present, such as house sharing, children responsibilities or shared properties. Besides, most of these instruments focus on the victimization of the questioned person, leaving aside the possibility that the victim might also be an aggressor, thus excluding an important factor: the bidirectional or reciprocal violence dynamic, which has been identified among adolescents and young people in numerous national and international studies. These studies have pointed out the reciprocal relationship between victimization and aggression in psychological dating violence (Fernández-González, O’Leary, & Muñoz-Rivas, 2013; Menesini, Nocentini, Ortega-Rivera, Sánchez, & Ortega, 2011; Orpinas, Nahapetyan, Song, McNicholas, & Reeves, 2012) and more specific instruments of psychological violence are needed to study the bidirectionality in dating couples and to evaluate different types of behaviours and attitudes, both subtle and overt.

The objectives of this study are: a) to develop the scale Psychological Dating Violence Questionnaire (PDV-Q) with a sample of university students and b) to analyze its reliability and validity. It is hypothesized that will be tested a bi-dimensional structure with aggression and victimization scales.

MethodThis instrumental study was carried out using an instrumental, transversal design (Montero & León, 2007).

ParticipantsA number of 849 university students was tested and people who had or had had heterosexual sentimental relationships in the last six months were selected. Homosexual cases were eliminated due to the percentage was not representative. A total of 670 university students took part in the study (37.2% males and 62.8% females). Female sample was higher because there is a population bias (54.37% females and 45.63% males) at the University of Cordoba (General Secretariat University of Cordoba, 2012). The selection of the sample group was incidental. The students were from all levels and different knowledge areas (22.8% from Health Sciences, 26.4% from Education Science, 19.9% from Engineer Science and 30.9% from Human Studies). The students aged between 19 and 25 at the moment of filling in the questionnaires (M=22; SD=1.78). Average of the length of their current relationships (M=134.11 weeks; SD=103.85) and previous ones (M=30.63 weeks; SD=44.06) were lower than three years.

Instruments- –

Socio-demographic data referred to sex, age, level and date of birth were questioned.

- –

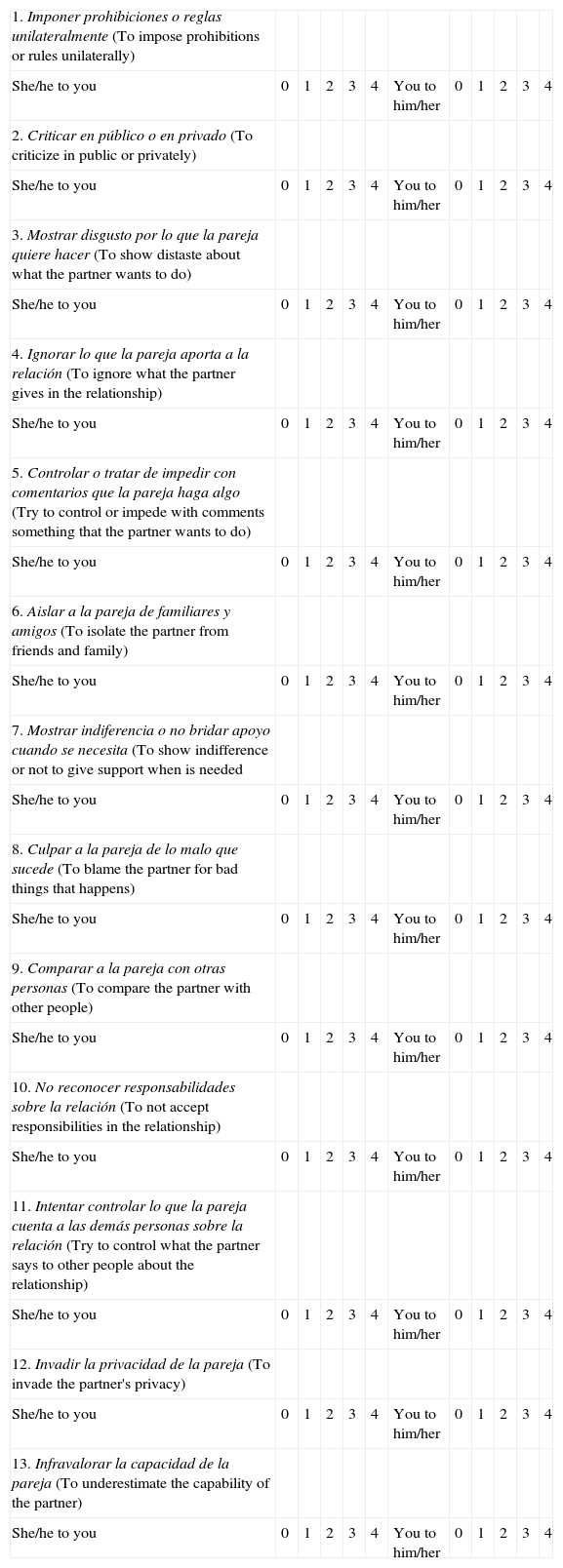

The Psychological Dating Violence Questionnaire (PDV-Q) was developed in this study with the aim of determining its psychometric properties. The items of the questionnaire were created taking into account recommendations from an expert panel about the aspects that have to be considered when psychological abuse is evaluated or defined (Saltzman, Fanslow, McMahon, & Shelley, 1999). Also the scales proposed in the Subtle and Overt Scale of Psychological Abuse (Marshall, 1999; adapted by Buesa & Calvete, 2011) were taken into account. Overt psychological abuse was defined by: Domination (i. e. “To impose prohibitions or rules unilaterally”), indifference (“To show indifference or not to give support when is needed”), monitoring (“To invade the partner's privacy”) and discredit (“To criticize in public or privately”). Subtle way was defined by: Undermine (“To underestimate the capability of the partner”), discount (“To show distaste about what the partner wants to do”) and isolate (“To isolate the partner from friends and family”) (see Appendix). The Likert response format (value range from 0=never to 4=always) was chosen to answer the frequency of involvement in aggressive or victim behaviors in each situation presented (you to him / her, or he / she to you). The scale was composed of 19 ways of psychological violence (19 items for aggression and 19 for victimization).

- –

Physical violence. An adapted version of the physical violence scale in the Conflict Tactics Scale-2 (CTS2) (Straus et al., 1996) was used. It was adapted by Nocentini, Menesini et al. (2011) to take into account the specific characteristics of adolescent dating relationships and validated in a sample of Spanish adolescents by Viejo, Sánchez and Ortega-Ruiz (2014). The final scale comprised 8 two-way items (aggression and victimization) that measured the frequency of adolescent involvement in different types of physical violence on a five-point Likert-type scale. The internal structure pointed out a two factor model for victimization (mild and severe behaviours) and for aggression (mild and severe behaviours), even when a unique factor solution was also possible (victimization vs. aggression) (Viejo et al., 2014). Due to the aim of this paper, we selected the unique factor solution: physical victimization (α=.91) and physical aggression (α=.93).

A pilot test was carried out with students from first year of the Humanities area of knowledge to ensure that all the items were understood. In order to guarantee the validity of content of the scale a group of international experts reviewed the items that best represented each dimension. Once the final version was designed we proceeded to inform of the research aims and applied for the deans’ permission to implement the instrument. Data was collected during two months. The instructions to fill in the questionnaires and the purposes of the research were explained to the students as well as the willfulness, confidentiality and anonymity of their responses.

Data analysisFollowing the recommendations of Neukrug and Fawcett (2014) for the validation of questionnaires, the sample was divided into two parts taking gender as the selection variable with a proportional number of females and males in order to proceed with the Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis and to make the cross-validation procedure, optimizing the generalization of the model by using different subsamples (Delgado-Rico, Carretero-Dios, & Ruch, 2012). We used FACTOR 9.2 statistical software recommended to work with polychoric matrix (Lorenzo-Seva & Ferrando, 2006) and Lisrel 9.1 for the Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Polychoric correlation was used. It is advised when the sample is not normal and the univariate distributions of ordinal items are asymmetric or with excess of kurtosis (Bryant & Satorra, 2012). Weighted oblimin rotation was used and the estimation was carried out with the unweighted least squares (ULS) method (Lorenzo-Seva, 2000). A standardized Cronbach¿s coefficient alpha was also calculated.

We took into account the following criteria to eliminate items: a) EFA: communalities below .40, factorial weight less than .32, and the difference between the weight factor of each pair of items (victimization-aggression) less than .15 (Worthington & Whittaker, 2006), b) CFA: loadings below .40 with high measurement errors (Flora & Curran, 2004; Flora, Finkel, & Foshee, 2003).

To evaluate the goodness of the proposed model fit was calculated: χ2 divided by degrees of freedom, root mean square residual (RMR), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), goodness of fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker and Lewis Index (TLI), and the parsimony index ECVI (Byrne, 2013; Hu & Bentler, 1999). A Pearson correlation analysis was used for the external validity analysis, recommended for the study of the predicted relationship between different constructs (Delgado-Rico et al., 2012). In this case, the psychological violence and the physical violence were measured. These types of violence may coexist or interrelate; in fact, previous researchers have found that psychological violence can precede physical violence (Muñoz-Rivas et al., 2007; O’Leary & Smith-Slep, 2003) or may occur simultaneously (Barreira, Carvalho, & Avanci, 2013; Tolman, 2001).

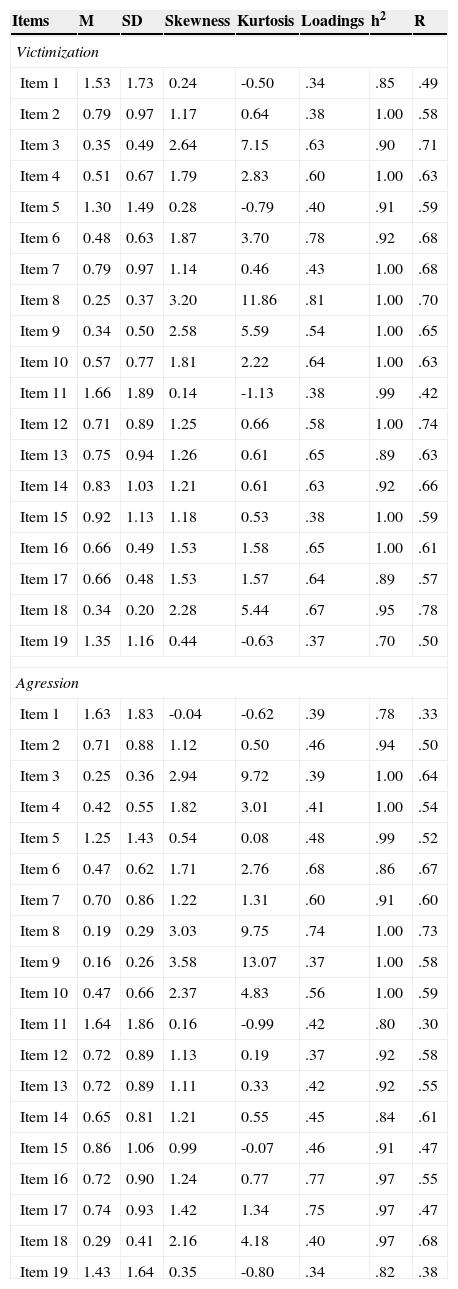

ResultsExploratory Factor AnalysisAn EFA was done to explore the number of scales and it was observed a clear differentiation between two factors: Aggression and Victimization, according with the theory. Later on, exploratory tests were made with a different number of factors but results were not conclusive. Keiser-Meyer-Olkin test and Barlett test showed satisfactory results for the double factor solution and revealed an optimum adequacy of the correlation matrix (KMO=.78), Barlett test result was p < .01 (Delgado-Rico et al., 2012). The total observed variance found was 38%. The majority of the items acquired values above .40 (Neukrug & Fawcett, 2014). Taking into account communalities and factorial weight values, according to the established criteria, items 1, 3, 11 and 19 for victimization and aggression were removed. The values found in the EFA are shown in the Table 1.

Univariate descriptive for the EFA.

| Items | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Loadings | h2 | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victimization | |||||||

| Item 1 | 1.53 | 1.73 | 0.24 | -0.50 | .34 | .85 | .49 |

| Item 2 | 0.79 | 0.97 | 1.17 | 0.64 | .38 | 1.00 | .58 |

| Item 3 | 0.35 | 0.49 | 2.64 | 7.15 | .63 | .90 | .71 |

| Item 4 | 0.51 | 0.67 | 1.79 | 2.83 | .60 | 1.00 | .63 |

| Item 5 | 1.30 | 1.49 | 0.28 | -0.79 | .40 | .91 | .59 |

| Item 6 | 0.48 | 0.63 | 1.87 | 3.70 | .78 | .92 | .68 |

| Item 7 | 0.79 | 0.97 | 1.14 | 0.46 | .43 | 1.00 | .68 |

| Item 8 | 0.25 | 0.37 | 3.20 | 11.86 | .81 | 1.00 | .70 |

| Item 9 | 0.34 | 0.50 | 2.58 | 5.59 | .54 | 1.00 | .65 |

| Item 10 | 0.57 | 0.77 | 1.81 | 2.22 | .64 | 1.00 | .63 |

| Item 11 | 1.66 | 1.89 | 0.14 | -1.13 | .38 | .99 | .42 |

| Item 12 | 0.71 | 0.89 | 1.25 | 0.66 | .58 | 1.00 | .74 |

| Item 13 | 0.75 | 0.94 | 1.26 | 0.61 | .65 | .89 | .63 |

| Item 14 | 0.83 | 1.03 | 1.21 | 0.61 | .63 | .92 | .66 |

| Item 15 | 0.92 | 1.13 | 1.18 | 0.53 | .38 | 1.00 | .59 |

| Item 16 | 0.66 | 0.49 | 1.53 | 1.58 | .65 | 1.00 | .61 |

| Item 17 | 0.66 | 0.48 | 1.53 | 1.57 | .64 | .89 | .57 |

| Item 18 | 0.34 | 0.20 | 2.28 | 5.44 | .67 | .95 | .78 |

| Item 19 | 1.35 | 1.16 | 0.44 | -0.63 | .37 | .70 | .50 |

| Agression | |||||||

| Item 1 | 1.63 | 1.83 | -0.04 | -0.62 | .39 | .78 | .33 |

| Item 2 | 0.71 | 0.88 | 1.12 | 0.50 | .46 | .94 | .50 |

| Item 3 | 0.25 | 0.36 | 2.94 | 9.72 | .39 | 1.00 | .64 |

| Item 4 | 0.42 | 0.55 | 1.82 | 3.01 | .41 | 1.00 | .54 |

| Item 5 | 1.25 | 1.43 | 0.54 | 0.08 | .48 | .99 | .52 |

| Item 6 | 0.47 | 0.62 | 1.71 | 2.76 | .68 | .86 | .67 |

| Item 7 | 0.70 | 0.86 | 1.22 | 1.31 | .60 | .91 | .60 |

| Item 8 | 0.19 | 0.29 | 3.03 | 9.75 | .74 | 1.00 | .73 |

| Item 9 | 0.16 | 0.26 | 3.58 | 13.07 | .37 | 1.00 | .58 |

| Item 10 | 0.47 | 0.66 | 2.37 | 4.83 | .56 | 1.00 | .59 |

| Item 11 | 1.64 | 1.86 | 0.16 | -0.99 | .42 | .80 | .30 |

| Item 12 | 0.72 | 0.89 | 1.13 | 0.19 | .37 | .92 | .58 |

| Item 13 | 0.72 | 0.89 | 1.11 | 0.33 | .42 | .92 | .55 |

| Item 14 | 0.65 | 0.81 | 1.21 | 0.55 | .45 | .84 | .61 |

| Item 15 | 0.86 | 1.06 | 0.99 | -0.07 | .46 | .91 | .47 |

| Item 16 | 0.72 | 0.90 | 1.24 | 0.77 | .77 | .97 | .55 |

| Item 17 | 0.74 | 0.93 | 1.42 | 1.34 | .75 | .97 | .47 |

| Item 18 | 0.29 | 0.41 | 2.16 | 4.18 | .40 | .97 | .68 |

| Item 19 | 1.43 | 1.64 | 0.35 | -0.80 | .34 | .82 | .38 |

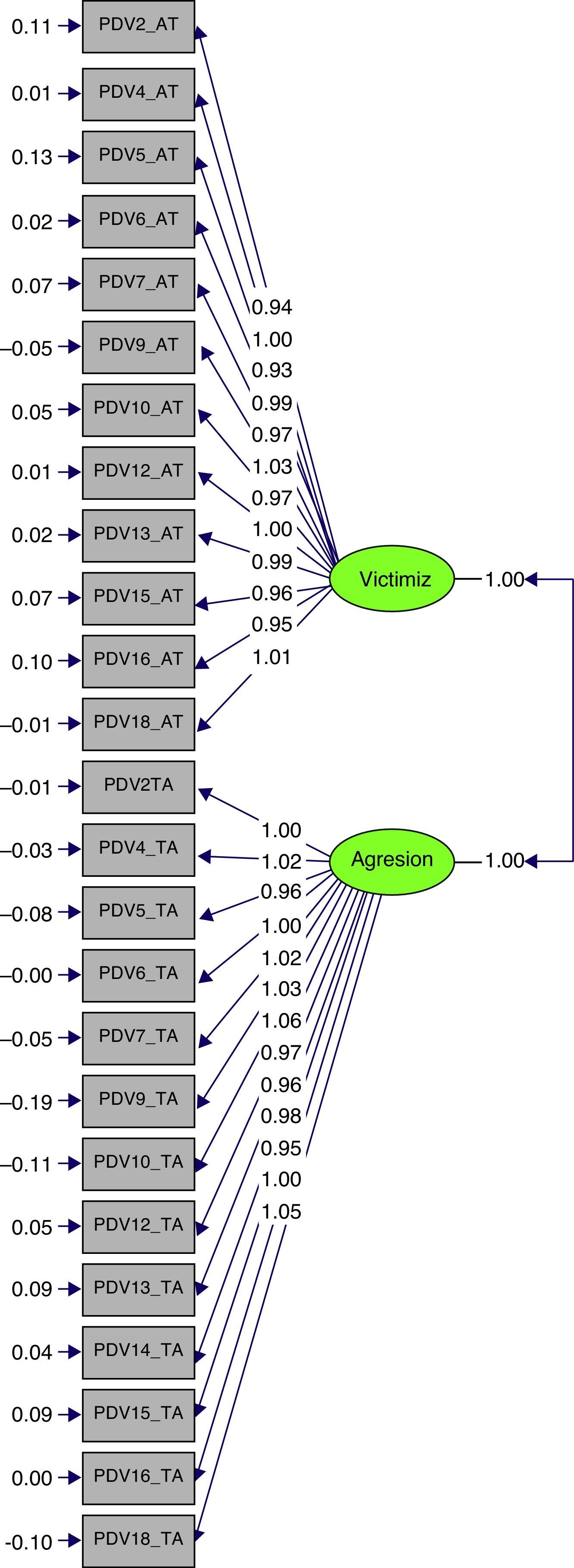

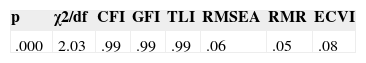

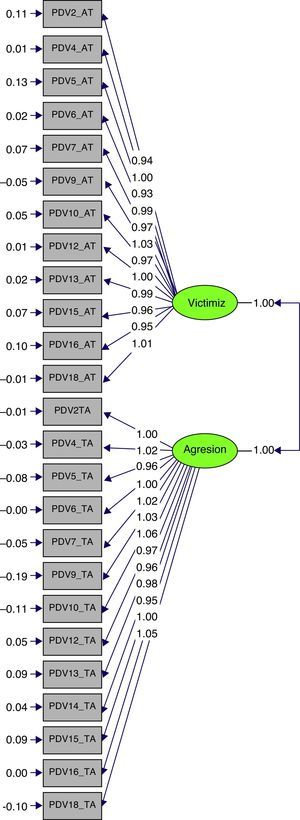

A Confirmatory Factor Analysis was carried out. Items 8 and 17, with correlation values higher than .8 were removed. Finally the questionnaire consists of 13 items for victimization and 13 for aggression (see Appendix). The CFA results confirmed the bi-dimensional model from the EFA (see Figure 1 and Table 2).

Reliability analysisThe reliability analysis showed Cronbach's values of .88 regarding victimization subscale, .85 regarding aggression subscale and a total value of .92 (Neukrug & Fawcett, 2014).

External validityCorrelation analyses between psychological and physical forms of violence were run to measure the external validity of the PDV-Q. The results showed that psychological aggression was positive and significantly related with physical aggression (.51) and physical victimization (.48). Psychological victimization was also significantly related with physical aggression (.42) and physical victimization (.48). Nonetheless, all the correlation values were medium-low, pointed out the differences between both concepts.

Discussion and conclusionsThe main objective of this study was to design a brief scale for assessing psychological dating violence among university students. Behaviors referred to disrespect, verbal aggression, unjustified jealousy, humiliation and control, could exist in these relationships. Such behaviours foul and contaminate communication and the positive feelings that love provides. A type of violence that enters into the relationship, and perhaps can be considered as the origin of other forms of violence more stable and dangerous in adulthood, like gender violence. It has been the starting point for an exploration with the instrument PDV-Q.

The PDV-Q has been designed and evaluated to describe and analyze the psychological violence in dating couples and to know its psychometric properties, following the standards for the development of instrumental studies (Carretero-Dios & Pérez, 2007). Evidences of validation centered in the dimensionality of this instrument allowed us to conclude that the PDV-Q has two subscales, victimization and aggression.

The PDV-Q design joins dating and intimate violence instruments potentialities, overcoming main difficulties reflected in literature; it includes a wide range of violent behaviours, both subtle and overt, adapting them to specific characteristics from young couples and considering them from a double perspective, as aggressor and as victim.

The PDV-Q developed in this study is a new measuring instrument, that distinguishes between aggression and victimization, which coincides in its univariate structure with other previous questionnaires focused on psychological violence, as the SOPAS (Buesa & Calvete, 2011; Jones et al., 2005) or the Inventory of Psychological Abuse in the Context of Couple Relationships (Calvete et al., 2005) and differs from other questionnaires that include different dimensions of psychological violence such as the Profile of Psychological Abuse (Sackett & Saunders, 1999).

The scales have good reliability, validity indices and good fit of the data (Byrne, 2013; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Neukrug & Fawcett, 2014). Reliability score (.95) is similar to other instruments of psychological violence: Subtle and Overt Psychological Abuse of Woman Scale (.97 overt, .96 subtle) (Jones et al., 2005; Marshall, 1999), Follingstad Psychological Aggression Scale (.98) (Follingstad, Coyne, & Gambon, 2005).

External validation results confirm that psychological violence maintains a relation of co-occurrence with physical violence (Coker, Smith, McKeown, & King, 2000) but supports the differences between both.

The limitations are mainly to the use of self-report instruments and social desirability bias attached. It would be avoided with the inclusion of partners’ reports. The sample belongs to a unique community university, which is the reason why we cannot generalize the results to the rest of the population. Also in this university student sample there is higher number of women than men, for that reason the gender is not balanced. Another limitation is that it was not possible to include homosexual students because the sample was not representative.

Future studies are needed to deepen the individual, contextual and relational characteristics that lead to psychological violence behaviours in young couples. It would also be necessary additional cross-cultural researches to observe if there are differences in the perception and meanings of these issues.

FundingThis research was conducted with funding from Proyecto del Plan Nacional I+D+i: Violencia Escolar y Juvenil (2010-17246).

| 1. Imponer prohibiciones o reglas unilateralmente (To impose prohibitions or rules unilaterally) | |||||||||||

| She/he to you | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | You to him/her | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2. Criticar en público o en privado (To criticize in public or privately) | |||||||||||

| She/he to you | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | You to him/her | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3. Mostrar disgusto por lo que la pareja quiere hacer (To show distaste about what the partner wants to do) | |||||||||||

| She/he to you | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | You to him/her | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4. Ignorar lo que la pareja aporta a la relación (To ignore what the partner gives in the relationship) | |||||||||||

| She/he to you | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | You to him/her | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5. Controlar o tratar de impedir con comentarios que la pareja haga algo (Try to control or impede with comments something that the partner wants to do) | |||||||||||

| She/he to you | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | You to him/her | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6. Aislar a la pareja de familiares y amigos (To isolate the partner from friends and family) | |||||||||||

| She/he to you | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | You to him/her | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 7. Mostrar indiferencia o no bridar apoyo cuando se necesita (To show indifference or not to give support when is needed | |||||||||||

| She/he to you | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | You to him/her | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 8. Culpar a la pareja de lo malo que sucede (To blame the partner for bad things that happens) | |||||||||||

| She/he to you | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | You to him/her | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 9. Comparar a la pareja con otras personas (To compare the partner with other people) | |||||||||||

| She/he to you | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | You to him/her | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 10. No reconocer responsabilidades sobre la relación (To not accept responsibilities in the relationship) | |||||||||||

| She/he to you | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | You to him/her | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 11. Intentar controlar lo que la pareja cuenta a las demás personas sobre la relación (Try to control what the partner says to other people about the relationship) | |||||||||||

| She/he to you | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | You to him/her | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 12. Invadir la privacidad de la pareja (To invade the partner's privacy) | |||||||||||

| She/he to you | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | You to him/her | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 13. Infravalorar la capacidad de la pareja (To underestimate the capability of the partner) | |||||||||||

| She/he to you | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | You to him/her | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

Available online 7 October 2014