The ongoing mental health crisis warrants investigations to understand why trait mindfulness is associated with beneficial mental health outcomes. This study examined attention monitoring and acceptance as psychological mechanisms underlying the relationship between trait mindfulness and emotion regulation and connectivity between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) as a potential neural mechanism.

MethodsA cross-sectional study was conducted with 501 adult participants (age range: 17–79, M = 31, SD = 11.3) representing the general population. To assess emotion regulation and trait mindfulness, participants completed the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) and Five Facets Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ). Resting-state functional MRI was acquired in a subsample of 20 participants to explore the role of dlPFC-PCC functional connectivity.

ResultsHigher levels of acceptance, as measured using the Non-judging and Non-reactivity subscales of the FFMQ, were significantly associated with fewer overall emotion regulation difficulties and predicted all emotion regulation subscales. In contrast, higher levels of attention monitoring, measured using the Observe subscale, predicted only three DERS subscales and with mixed effects: higher emotional awareness and clarity, but greater difficulties in goal-directed behaviour. The interaction between monitoring and acceptance was not significant, and no correlation was found between these variables and dlPFC-PCC functional connectivity.

ConclusionsThese findings challenge previous theories that argue that attention monitoring is crucial for effective emotion regulation. Instead, we conclude that acceptance is the key psychological mechanism, indicating that the traditional focus on attention monitoring in mindfulness training may be less effective than a primary emphasis on acceptance. This study provides a critical review of past research, highlighting issues with operationalising acceptance, and offers recommendations for future studies and practical implications for developing mindfulness interventions.

Mental health has become a significant concern worldwide, as the number of people struggling with mental health problems continues to rise (Twenge et al., 2019; Sohn, 2022). Recent studies point to emotion regulation as a key factor to examine when attempting to understand what can protect mental health, because it is a transdiagnostic construct that is relevant to many, if not all, mental health problems (Cludius et al., 2020; Sloan et al., 2017). Effective emotion regulation is crucial for maintaining mental health, but we do not understand what contributes to the variability in emotion regulation in the general population. In this context, trait mindfulness emerges as a promising area of research.

Trait mindfulness is a construct that has well-established positive effects on emotion regulation (McLaughlin et al., 2019; Fisher et al., 2022; Schirda et al., 2015; Mesmer-Magnus et al., 2017). Trait mindfulness varies in the general population and refers to a person's general tendency to be aware of their present-moment experiences—including thoughts, emotions, bodily sensations, and action tendencies—without judgement or reactivity (Brown et al., 2007). One hypothesis on why trait mindfulness benefits emotion regulation is advanced by a recent psychological theory: the Monitor and Acceptance Theory (MAT). MAT posits that attention monitoring and acceptance are the fundamental psychological mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of trait mindfulness on emotion regulation (Brown et al., 2007). Attention monitoring refers to the awareness of present-moment experiences—including thoughts, emotions, bodily sensations, and action tendencies—while acceptance involves an open, non-judgmental attitude towards these experiences (Tomlinson et al., 2018; Sala et al., 2019). MAT has two main tenets that are specifically related to emotion regulation. First, attention monitoring enhances awareness of present-moment experience, and can thus intensify both pleasant and unpleasant experiences, which may or may not contribute to emotion regulation (Lindsay & Creswell, 2019). Second, when combined with acceptance, attention monitoring can foster emotion regulation and promote beneficial outcomes by modifying the relationship with experiences that are being observed (Lindsay & Creswell, 2019). More specifically, this means that attention monitoring and acceptance interact so that high levels of monitoring paired with low acceptance are not beneficial for emotion regulation, while high levels of monitoring paired with high acceptance are beneficial for emotion regulation. MAT thus proposes that both attention monitoring and acceptance are necessary for emotion regulation. However, empirical evidence supporting these predictions is currently limited. There is only partial and non-replicated evidence of a direct effect of monitoring on psychological outcomes, as well as unreliable evidence of a moderating effect of acceptance on the relationship between monitoring and psychological outcomes (Simione & Saldarini, 2023). A recent critical review of the MAT (Simione & Saldarini, 2023) raises multiple questions regarding the theory's tenets after a substantial literature review and suggests that acceptance alone could be sufficient for the beneficial effects of trait mindfulness on emotion regulation. In fact, Wang et al. (Wang et al., 2019) showed that acceptance alone is a better strategy for pain management than both attention monitoring, as well as attention monitoring combined with acceptance, while Simione and Saldarini (Simione et al., 2021) found no moderation effect of monitoring and acceptance on well-being. This direct evidence against MAT's predictions suggests a potential need to reshape the theory to accommodate a more principal role of acceptance. This inconsistency in the literature underscores the need for further investigation into how attention monitoring and acceptance interact as psychological mechanisms that influence emotion regulation.

In terms of neural mechanisms, recent studies have begun to detect neural correlates that may explain the emotion regulation benefits of mindfulness. Studies using resting-state functional connectivity (rs-FC), a widely used approach in neuroimaging, point to increases in rs-FC between the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) as a potential neural mechanism. This has been found following mindfulness-based interventions (Kral et al., 2019; Creswell et al., 2016; Hafeman et al., 2020; Scult et al., 2019; King et al., 2016; Sezer et al., 2022), but the direct relationship of dlPFC-PCC with trait mindfulness and emotion regulation remains unknown. The PCC is a key hub of the default mode network (DMN), which has been related to mind wandering, rumination, and self-evaluation, whereas the dlPFC is associated with cognitive control functions as part of the executive control network (ECN) (David Creswell et al., 2019; Raichle et al., 2001). These findings suggest that increased dlPFC-PCC connectivity may reflect enhanced attentional control over mind wandering and self-referential processes, thereby contributing to emotion regulation benefits of trait mindfulness (Kral et al., 2019; Hafeman et al., 2020). This interpretation is in line with a prominent psychological theory—he process model of emotion regulation (Gross, 1999; Ochsner & Gross, 2005; Loeffler et al., 2019; O'Bryan et al., 2017) —positing that greater attentional control facilitates the effective use of emotion regulation strategies, which reinforces the importance of examining these neural connections. Therefore, exploring the relationship between dlPFC-PCC connectivity and psychological variables related to emotion regulation and trait mindfulness can provide further insights into this neural variable as a promising neural marker of emotion regulation.

The current study aims to go beyond currently available unidimensional theories by testing psychological and neural variables related to emotion regulation to provide a more nuanced understanding of attention monitoring and acceptance in emotion regulation, and to explore the neural correlates of these mechanisms. First, in terms of psychological mechanisms, we aim to test the roles of attention monitoring and acceptance in emotion regulation. According to the MAT, acceptance should moderate the effects of attention monitoring so that high monitoring paired with high acceptance should lead to better outcomes. For that reason, we investigate whether attention monitoring and acceptance independently predict emotion regulation, or if the interaction between attention monitoring and acceptance (i.e., moderation term) provides additional explanatory power. We hypothesise that both acceptance and attention monitoring independently predict overall emotion regulation (H1), and that the interaction between acceptance and attention monitoring predicts emotion regulation and explains additional variance (H2). In addition to predicting overall emotion regulation, we explored constituent components of emotion regulation to generate hypotheses for future studies. Next, in terms of neural mechanisms, we aim to explore the relationship between dlPFC-PCC connectivity, emotion regulation and trait mindfulness. We hypothesise that dlPFC-PCC functional connectivity will be positively correlated to overall trait mindfulness, acceptance, and attention monitoring, as well as to emotion regulation (H3), indicating that individuals with higher levels of trait mindfulness and better emotion regulation may demonstrate increased functional connectivity between the PCC and dlPFC. With these aims in mind, we conducted a cross-sectional study with a non-clinical sample of adults who are not regular mindfulness meditation practitioners to capture a range of trait mindfulness levels that naturally occur in the general population.

Materials and methodsParticipantsThis cross-sectional study includes a combination of datasets collected by our research team as a part of other mindfulness research projects conducted between 2021 and 2024 using similar methodologies and outcome measures. More information about each dataset and data pooling procedures can be found in the Supplement. The final pooled dataset comprised 501 participants whose ages ranged from 17 to 79 (M = 31, SD = 11.3). Most participants identified as female (81.5 %), 17.7 % as male, and 0.8 % as non-binary or other. For the total sample of 501 participants, the main inclusion criterion was to be over 17 years of age, and the main exclusion criterion was having a regular mindfulness practice currently or in the past (defined as at least 15 min of practice three times per week for a period of at least two months). All participants filled out questionnaires via Qualtrics. A subsample of 20 randomly selected participants additionally underwent neuroimaging at the University of Amsterdam.

Outcome measuresEmotion regulationThe Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) is a 36-item scale measuring several aspects of emotion regulation (Gratz & Roemer, 2004). The self-report instrument assesses the extent to which participants struggle with emotion regulation (e.g., ‘I am confused about how I feel’) on the following six subscales: Non-acceptance of Emotional Responses, Difficulty Engaging in Goal-directed Behaviour, Impulse Control Difficulties, Lack of Emotional Awareness, Limited Access to Emotion Regulation Strategies and Lack of Emotional Clarity. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The total score ranges from 36 to 180, with higher scores indicating greater difficulties in emotion regulation. The DERS has been shown to have high internal consistency, good test-retest reliability, adequate construct and predictive validity (Gratz & Roemer, 2004). Reliability analyses showed that the instrument has a high reliability, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.92.

Trait mindfulnessTrait mindfulness was measured with The Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) (Baer et al., 2006). The FFMQ consists of 39 items that focus on five facets of mindfulness: Observing (observing of experiences and feelings), Describing (describing experiences with words), Acting with awareness (being aware and not distracted), Non-judgment (accepting experiences, thoughts and feelings) and Non-reactivity (noticing thoughts and feelings without reacting). It contains items like ‘When I'm walking, I deliberately notice the sensations of my body moving’ and ‘I watch my feelings without getting lost in them’. The items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Never or very rarely true) to 5 (very often or always true). The total score ranges from 39 to 195, with higher total scores indicating higher levels of mindfulness. The FFMQ has been shown to be a valid instrument to measure mindfulness with an internal consistency ranging from adequate to good (Baer et al., 2006). Intercorrelations are moderate between facets, which is an indication of distinct measures in each facet (Baer et al., 2006). The reliability analysis showed that this questionnaire has a high reliability, Cronbach's alpha = 0.90.

dlPFC-PCC resting state functional connectivityFor the subsample of 20 randomly selected participants, high resolution (1 × 1 × 1 mm) T1-weighted structural scans were collected during rest via a 3T scanner. Resting state functional MRI (rs-fMRI) data was acquired using a MB4 Sequential scan, multiband sequence with shimbox and top up correction. The following parameters were used: resolution = 2 mm³, TR = 1600 ms (± 8 min). During the rs-fMRI scan, participants were instructed to look at the fixation cross and to stay awake and let their mind wander. Total duration of the scan was approximately 15 min. For more information on neuroimaging data procedures, see the Supplement.

Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were conducted in the latest available version of Jamovi 2.4.14. We began by conducting checks to see if the pooling of multiple datasets was justified. We ran descriptive analyses and intercorrelations among the main variables within each dataset and checked for group differences between datasets (See Table S1 of the Supplementary material for results). Based on the original publication on the MAT (Lindsay & Creswell, 2017) and subsequent work (Simione et al., 2021), the main constructs for the current study, i.e. acceptance and attention monitoring, were operationalised as follows: First, the FFMQ facet Observe was used to measure attention monitoring. Second, to measure acceptance, a composite score of facets Non-reactivity and Non-judgement has been suggested (Lindsay & Creswell, 2017). However, this approach to acceptance is considered problematic, as it merges two distinct aspects of acceptance, and obscures their unique contributions (Simione et al., 2021). As a result, Non-reactivity and Non-Judgment were examined as two separate components of acceptance in our main analyses. To allow comparisons across studies, we additionally repeated the main analysis (hierarchical regression) with the former to compare the results.

After pooling the datasets, we first ran descriptive analyses on the total sample, and calculated Pearson's correlation coefficients for the main variables. To validate the assumptions for the hypotheses, we initially assessed the normality of the variables, which the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test indicated was normally distributed. Considering the sample size, we selected this goodness-of-fit test, and additionally inspected histograms and scatter plots. This further validated assumptions on linearity and homoscedasticity. Raw data was used to determine Cronbach's alpha for the questionnaires using reliability analyses. To assess hypotheses H1 and H2, we conducted hierarchical linear regression analyses. For the hierarchical regression, age and gender (female, male, non-binary) entered the model in the first step, Non-judging, Non-reactivity, and Observe in the second step, and in the final step an interaction terms between Observe and Non-judging and Observe and Non-reactivity was added to test for moderation effects. Additionally, as mentioned above, the same analysis was repeated using acceptance calculated as the sum of Non-judging and Non-reactivity.

Exploratory analyses in the subsample with neuroimaging data were performed by conducting Pearson's correlation analyses among overall emotion regulation difficulties, Non-judging, Non-reactivity and Observe and z-scores of rs-FC between PCC and dlPFC. Assumptions on normality and linearity were considered and met, with validation achieved through the examination of Shapiro-Wilk test results, histograms, and scatter plots.

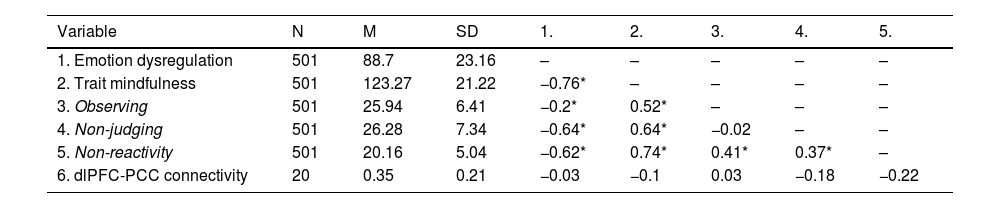

ResultsThe statistical descriptives and correlations are shown in Table 1. Bivariate correlations were estimated to assess the simple associations among the primary variables. Overall emotion dysregulation (measured as DERS total score) was negatively correlated with acceptance (measured as FFMQ facets Non-reactivity and Non-judgment) and attention monitoring (FFMQ facet Observe) and overall trait mindfulness (total FFMQ score). Non-reactivity and Observing were positively associated with each other, while Non-judging and Observing were not correlated. Further correlations with dlPFC-PCC connectivity are reported in the Exploratory analyses paragraph.

Descriptive statistics and correlations between psychological variables in the main sample (N = 501) and dlPFC-PCC connectivity with psychological variables in the subsample (N = 20).

| Variable | N | M | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotion dysregulation | 501 | 88.7 | 23.16 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2. Trait mindfulness | 501 | 123.27 | 21.22 | −0.76* | – | – | – | – |

| 3. Observing | 501 | 25.94 | 6.41 | −0.2* | 0.52* | – | – | – |

| 4. Non-judging | 501 | 26.28 | 7.34 | −0.64* | 0.64* | −0.02 | – | – |

| 5. Non-reactivity | 501 | 20.16 | 5.04 | −0.62* | 0.74* | 0.41* | 0.37* | – |

| 6. dlPFC-PCC connectivity | 20 | 0.35 | 0.21 | −0.03 | −0.1 | 0.03 | −0.18 | −0.22 |

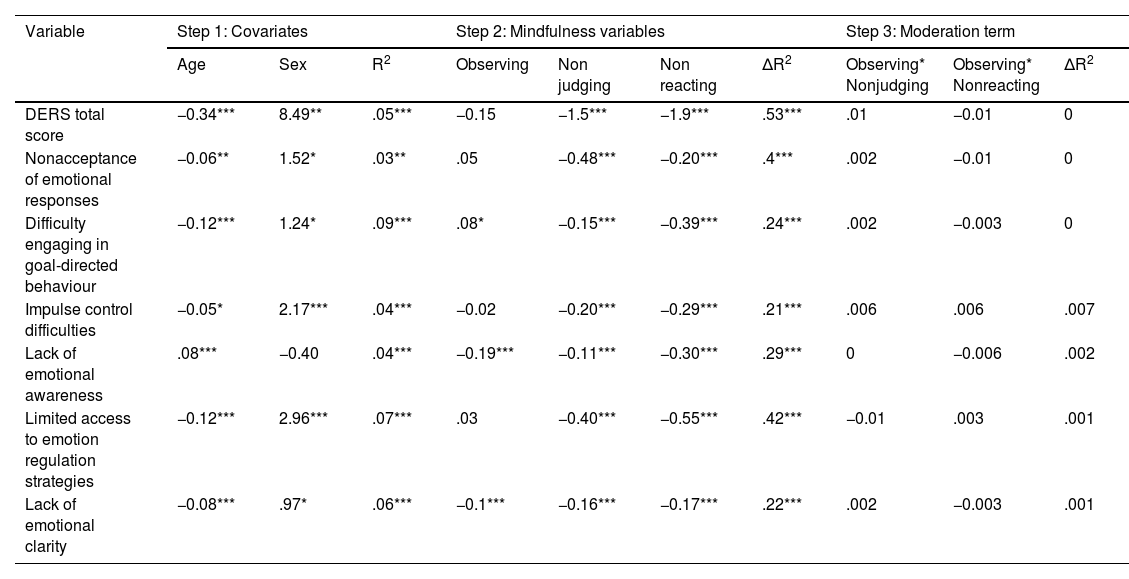

According to the first aim of our study, we conducted hierarchical linear regression. Results are summarised in Table 2. In the first step, we introduced age and gender, which explained a significant proportion of variance in emotion dysregulation and its subscales (ranging from 3 to 9 percent). Introducing Non-judging, Non-reactivity and Observe in the next step, explained significant additional variance in both overall emotion dysregulation and its subscales. Age, gender, Non-judging, Non-reactivity and Observe explained most of the variance of overall emotion dysregulation (58 %) and least variance in the subscale Impulse control difficulties (25 %). It is important to note that Non-judging and Non-reactivity were significant predictors for all outcome variables, whereas the Observe subscale only predicted the DERS subscales Difficulty engaging in goal-directed behaviour, Lack of emotional awareness and Lack of emotional clarity. In the last step, when the interaction terms between Observe and Non-judging and Observe and Non-reactivity were introduced to test for a moderation effect, no significant interactions were found.

Hierarchical regression results for step 1 (covariates), step 2 (MAT variables), and step 3 (moderation terms) predicting DERS and its subscales (N = 501).

| Variable | Step 1: Covariates | Step 2: Mindfulness variables | Step 3: Moderation term | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Sex | R2 | Observing | Non judging | Non reacting | ΔR2 | Observing* Nonjudging | Observing* Nonreacting | ΔR2 | |

| DERS total score | −0.34*** | 8.49** | .05*** | −0.15 | −1.5*** | −1.9*** | .53*** | .01 | −0.01 | 0 |

| Nonacceptance of emotional responses | −0.06** | 1.52* | .03** | .05 | −0.48*** | −0.20*** | .4*** | .002 | −0.01 | 0 |

| Difficulty engaging in goal-directed behaviour | −0.12*** | 1.24* | .09*** | .08* | −0.15*** | −0.39*** | .24*** | .002 | −0.003 | 0 |

| Impulse control difficulties | −0.05* | 2.17*** | .04*** | −0.02 | −0.20*** | −0.29*** | .21*** | .006 | .006 | .007 |

| Lack of emotional awareness | .08*** | −0.40 | .04*** | −0.19*** | −0.11*** | −0.30*** | .29*** | 0 | −0.006 | .002 |

| Limited access to emotion regulation strategies | −0.12*** | 2.96*** | .07*** | .03 | −0.40*** | −0.55*** | .42*** | −0.01 | .003 | .001 |

| Lack of emotional clarity | −0.08*** | .97* | .06*** | −0.1*** | −0.16*** | −0.17*** | .22*** | .002 | −0.003 | .001 |

Repeating this analysis with acceptance calculated as sum of Non-judging and Non-reactivity yielded similar results and conclusions. To avoid repetitiveness in the main text, those results can be found in Tables S2 and S3 in the Supplementary Material.

Correlates of dlPFC-PCC connectivityFor the exploratory neural analyses, we used the subsample data of 20 participants that had undergone neuroimaging. As shown in Table 1, rs-FC between dlPFC and PCC was not significantly correlated with any of the psychological variables (overall emotion dysregulation, overall trait mindfulness, and Non-judging, Non-reactivity, and Observe subscales). The highest correlation was with Non-reactivity (−0.22), but this effect was not significant. Results are shown in Table 1.

DiscussionThe current study aimed to investigate the role of attention monitoring and acceptance, two key components of (trait) mindfulness in relation to emotion regulation to provide a more nuanced understanding of how mindfulness may benefit emotion regulation, and to explore potential neural correlates of these mechanisms. Based on the MAT theory, we predicted that both acceptance and attention monitoring would independently and significantly predict overall emotion regulation, and we explored predictions for emotion regulation subscales.

Our findings revealed that only acceptance, measured by Non-judging and Non-reactivity subscales of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ), significantly predicted emotion regulation. Higher levels of acceptance were associated with fewer overall difficulties in emotion regulation, and both Non-judging and Non-reactivity independently predicted all DERS subscales, highlighting their crucial role across different aspects of emotion regulation. In contrast, attention monitoring, measured by the Observe subscale, predicted only three subscales and in varying directions, with higher levels of attention monitoring being associated with increased difficulties in goal-directed behaviour, but also with higher emotional awareness and clarity. This suggests that while individuals skilled in observing can recognise and be aware of their emotions, they might have difficulties or be less inclined to engage in goal-directed behaviour, thus lacking an important means of regulating emotions.

We also tested the second tenet of the MAT, which posits that high levels of monitoring paired with high acceptance lead to less reactivity and better emotion regulation (Lindsay & Creswell, 2019). However, our results showed that the interaction between attention monitoring and acceptance was not significant and did not explain more variance than each factor independently. This finding suggests that the two components operate independently rather than synergistically to enhance emotion regulation. Our findings align with those of other studies, such as Simione et al. (Simione et al., 2021), which found that monitoring alone marginally predicted negative outcomes, while acceptance consistently predicted positive outcomes, such as reductions in psychological symptoms and increased well-being, with no significant interaction between monitoring and acceptance.

Our results challenge commonly accepted views of mindfulness, which emphasise the centrality of observing one's experiences. These findings are in line with previous studies that found inconsistencies in the factor structure of the FFMQ where observing does not always seem to fit neatly within the overall trait mindfulness construct, particularly among non-meditators (Baer et al., 2006; Lilja et al., 2011; Pang & Ruch, 2019), which led some researchers to suggest removing the Observe scale from the FFMQ when used with non-meditators (Duan, 2016). While this might be premature given the mixed results regarding the benefits of attention monitoring (Mattes, 2019), we suggests that the Observe scale may need to be carefully considered, particularly when applied to non-meditating populations. This issue becomes clearer when we look at the items measuring attention monitoring as Observe subscale of the FFMQ. This subscale primarily captures the observation of external stimuli (e.g., “I pay attention to sounds, such as clocks ticking, birds chirping, or cars passing”) and bodily sensations (e.g., “When I'm walking, I deliberately notice the sensations of my body moving”) rather than directly focusing on the observation of emotions and thoughts, which would be more aligned with the theory. This broader definition of attention monitoring within the Observing scale of FFMQ may have added a level of imprecision in the results that we here reported, thus future studies should test if these results will be replicated when attention monitoring is measured more directly as observing thought and emotions. Similarly, although Lindsay and Creswell (Lindsay & Creswell, 2017) suggested measuring acceptance using a composite score of Non-judging and Non-reactivity facets of the FFMQ, several studies have reported differential results when examining these facets separately (Barnes & Lynn, 2010; Eisenlohr-Moul et al., 2012; Curtiss et al., 2017; Desrosiers et al., 2014; Lau et al., 2018). This is not surprising given that, like several other studies (Baer et al., 2006; Lilja et al., 2011; Baer et al., 2008; Michalak et al., 2016), our study found a non-significant correlation close to zero between Observing and Non-judging, and a significant correlation between Observing and Non-reactivity. These findings highlight the need for further investigation into the distinct roles of these facets in acceptance research.

While we propose acceptance as a key psychological mechanism underlying the positive effects of mindfulness, it is essential to recognise challenges with its construct validity. Within the MAT framework, acceptance is defined in a way that closely aligns with equanimity, a broader construct than acceptance alone. Specifically, MAT theory defines acceptance as:

„Acceptance is an attitude of receptivity and equanimity toward all momentary experiences that allows even stressful stimuli to arise and pass without reactivity. “ (Lindsay et al., 2018)

„We use ‘acceptance’ as an umbrella term to describe an orientation of receptivity and non-interference with present-moment experiences… acceptance and equanimity break the typical association between desire (i.e., wanting and not wanting) and the hedonic tone (i.e. pleasant and unpleasant) of experiences.“ (Lindsay & Creswell, 2019)

This way of defining acceptance diverges from other definitions in psychological science, and other researchers have described problems of accurately defining and measuring acceptance (Wojnarowska et al., 2020; Williams & Lynn, 2010). In fact, the definition of acceptance used in MAT closely matches the established definitions of equanimity:

“Equanimity can be defined as an even-minded mental state or dispositional tendency toward all experiences or objects, regardless of their origin or their affective valence (pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral).” (Desbordes et al., 2015)

“…equanimity as the decoupling of desire (wanting and not wanting) from the hedonic tone of current or anticipated experience (pleasant and unpleasant)… equanimity is manifested by an intentional attitude of acceptance toward experience regardless of its hedonic tone, as well as by reduced automatic reactivity to the hedonic tone of experience.” (Hadash et al., 2016)

Different words (acceptance and equanimity) are thus used to refer to the same construct. This overlap also translates into the way in which acceptance and equanimity are operationalised. For instance, a validated equanimity questionnaire has a two-factor structure: acceptance and non-reactivity (Cheever et al., 2022). Similarly, the MAT proposes measuring acceptance as a combination of subscales from established mindfulness questionnaires, such as non-judgment—which is comparable to acceptance—and non-reactivity subscales of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (Lindsay & Creswell, 2017), which was the approach applied in this study. We can see that in both instances, the construct is defined as non-reactivity, meaning being able to stay with a present-moment experience and allowing it to pass without reacting, and as accepting/non-judging. Overall, referring to this construct as equanimity in future research may be more accurate.

In summary, we found that people with higher levels of trait mindfulness experience fewer emotion regulation difficulties. This finding is in line with previous research demonstrating the beneficial effects of trait mindfulness on mental health outcomes (Sala et al., 2019), as emotion regulation is a transdiagnostic component of various mental health conditions (Cludius et al., 2020; Sloan et al., 2017). Our results, however, contrast with the core predictions of MAT, instead supporting the perspective that mindfulness's benefits stem primarily from acceptance, rather than a combination of acceptance and attention monitoring. While this was not originally predicted by the MAT, the authors discussed the possibility that acceptance alone could be responsible for the positive effects of mindfulness, considering this an "alternative" to their tenet 2b (Lindsay & Creswell, 2019) and others have argued that this stance is more supported by empirical studies (Simione & Saldarini, 2023). Our study supports and extends findings from a recent cross-sectional study specifically testing MAT tenets that found more evidence supporting the core role of acceptance over its interaction with monitoring when it comes to common mental health problems (Simione et al., 2021). These previous and our current findings regarding trait mindfulness in the general population are aligned with literature showing that acceptance alone is associated with various positive outcomes including reduced stress, depression, and anxiety (Cash & Whittingham, 2010; Hamill et al., 2015), decreased post-traumatic stress symptoms (Vujanovic et al., 2009; Wahbeh et al., 2011), and lower levels of worry, rumination, and negativity bias (Fisak & Von Lehe, 2012; Paul et al., 2013); and the findings of a systematic review on the active components of mindfulness interventions (Stein & Witkiewitz, 2020) that included eight dismantling studies of mindfulness-based interventions and concluded that the essential active component of mindfulness interventions is some form of acceptance.

These insights suggest that the emphasis on attention monitoring in mindfulness practices may stem more from traditional teaching methods than from empirical evidence. While attention monitoring does play a role—as indicated by our regression analysis, which shows its contribution to emotional awareness and clarity—the primary focus of mindfulness interventions should be on cultivating and embodying acceptance. Framing mindfulness primarily as “attention training” could be harmful due to an accidental cultivation of attention monitoring over acceptance. Standardised mindfulness interventions, such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, typically aim to foster both attention and acceptance, but it may be more effective for these interventions to place greater emphasis on acceptance, as supported by recent dismantling trials (Stein & Witkiewitz, 2020). The unintended overemphasis on attention monitoring could help explain some of the adverse effects of mindfulness (Farias et al., 2020). While mindfulness research over recent decades has primarily investigated positive effects, negative effects have also been observed, especially as practicing mindfulness can be challenging at times (Lindahl et al., 2017) and for some people in some situations might be contraindicated (Buric et al., 2022).

Unlike psychological mechanisms, the state of the art of neural mechanisms in mindfulness research is less conclusive and our study did not manage to shed much light. Despite solid theoretical and empirical foundations that suggest that dlPFC-PCC should be one of the most relevant neural variables in mindfulness research (Hafeman et al., 2020), our analyses of dlPFC-PCC did not show significant correlations with attention monitoring, acceptance, overall trait mindfulness or emotion regulation. However, these results must be taken with caution given that neuroimaging data was available only for 20 participants (while the psychological data included 501 (see Table 1)), thus substantially underpowering our analyses to detect small or medium-sized effects. Although small sample sizes are common in the neuroimaging literature (Szucs & JPa, 2020), they increase the likelihood of both Type I and Type II errors (Szucs & JPa, 2020; Button et al., 2013). Type II errors occur when true effects go undetected, leading to false negatives, while Type I errors may arise due to inflated effect sizes in small samples (Szucs & JPa, 2020; Button et al., 2013). Our results should thus be interpreted cautiously, as the small sample size may have reduced our ability to detect subtle yet meaningful effects on the neural correlates of trait mindfulness. In addition to insufficient statistical power, another explanation for the null findings could be that dlPFC-PCC connectivity is more relevant for measuring mindfulness-based intervention outcomes and reflects early stages of learning mindfulness techniques (Creswell et al., 2016; Hafeman et al., 2020) rather than trait mindfulness variations in the general population as examined in the current study. To differentiate between these alternatives, large samples are needed to improve statistical power ensuring that observed findings are reliable and replicable (Poldrack et al., 2017; Marek et al., 2022). Future research in this area should aim to increase participant numbers or leverage collaborative data-sharing frameworks, such as the ENIGMA Consortium (Ganesan et al., 2024) where a meditation-related working group has recently been established (Thompson et al., 2022), which combine data from multiple labs to achieve greater statistical power to ensure that the observed effects are robust, replicable, and generalisable.

ConclusionOverall, this study contributes to the understanding of the mechanisms that explain associations between mindfulness, emotion regulation and mental health and contribute to the development of effective therapies. Our findings highlight the importance of acceptance in promoting effective emotion regulation. These findings have implications for the implementation of mindfulness-based interventions, as they suggest that cultivating acceptance may be particularly important for promoting effective emotion regulation and overall mental health.

Ethical approvals were obtained by the Ethics Review Board of the University of Amsterdam. This work was supported by the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions Postdoctoral Fellowship, grant agreement ID: 101033080 awarded to IB. IB contributed to the study conception and design, material preparation, data collection, supervising, writing the first draft of the manuscript and editing later versions. LZ contributed to data preparation and analyses, as well as editing the manuscript. AO contributed to neuroimaging data preparation and processing. MK contributed to editing the manuscript. GC contributed to editing the manuscript and supervising. All co-authors reviewed the final manuscript.

We thank all our participants for contributing to this research, as well as to all research interns who contributed to data collection.