The aim of the current cross-sectional study is to assess the relations between emotion dysregulation, psychological distress, emotional eating, and BMI in a sample of Italian young adults (20-35).

MethodsA total sample of 600 participants frm the general population, were asked to fill in demographical and physical data, the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale, the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale, and the Emotional Eating subscale of the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire via an online anonymous survey. Relations between variables have been inspected using a path model.

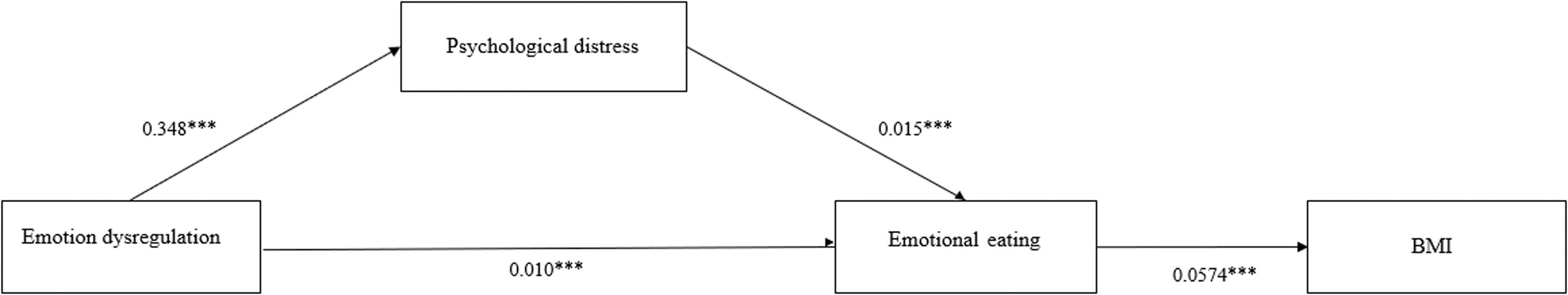

ResultsResults showed that emotion dysregulation was a contributor to higher levels of psychological distress [b= 0.348; SE: 0.020; p=<0.001; 95% BC-CI (0.306–0.387)] and emotional eating [b= 0.010; SE: 0.002; p=<0.001; 95% BC-CI (0.006–0.014)] which in turn, was related to higher Body Mass Index [b= 0.0574; SE: 0.145; p=<0.001; 95% BC-CI (0.286–0.863)].

ConclusionsBy providing additional evidence concerning the role of emotion dysregulation for physical and psychological outcomes, the current study could inform for improving psychological interventions aimed to promote emotion regulation strategies aimed at fostering physical and psychological well-being.

Emotion regulation is a multifaced process entailing the ability to be aware and accept experienced emotions, as well as to behave following personal goals, even when negative emotions are present while controlling impulsive behaviors (Gratz & Roemer, 2004). Emotion regulation has a crucial involvement in both physical and mental health (Gross & Muñoz, 1995). Several studies showed that whereas adapted emotion regulation strategies play a protective role against negative emotions and help people to cope with stressful life events (Bonanno, 2004), failures in emotion regulation were found to be involved in a plethora of physical and psychological problems including, among others, psychological distress, anxiety disorders, depression (Forman et al., 2009; Mennin et al., 2002), post-traumatic stress disorder (Villalta et al., 2020), borderline personality disorder (Miano et al., 2017) and sleep disturbances (Vandekerckhove & Wang, 2018). Moreover, when emotions are dysregulated, people may indulge in impulsive eating behaviors, as eating in response to negative feelings. This process is based on emotional eating.

Emotional eating is defined as “the tendency to eat in response to negative emotions” (van Strien et al., 1986). Given its association with consuming high-calorie food (Pinaquy et al., 2003b), emotional eating has been related to physical problems, including weight gain, as well as poor psychological outcomes such as distress, depression, eating disorders, and poor psychological well-being (Bentham et al., 2017; Cecchetto et al., 2021; Chu et al., 2019; Nguyen-Rodriguez et al., 2009; Spinosa et al., 2019). As a disordered eating behavior and a strategy to cope with negative feelings, emotional eating has been associated with stressful or traumatic events. Not surprisingly, since the COVID-19 outbreak rates of emotional eating increased (Echeverri-Alvarado et al., 2020; Harrington et al., 2006; Scarmozzino & Visioli, 2020; van Strien, 2018). In Italy, a recent study showed that the high level of psychological distress experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic was a contributor to determining an increase in emotional eating, through emotional dysregulation (Guerrini Usubini et al., 2021). Unfortunately, no associations between emotional eating and increased Body Mass Index (BMI), registered in the Italian population during the COVID-19 lockdown (Di Renzo et al., 2020) were assessed. However, in many studies, emotional eating has been depicted as a reason for increased BMI or even, a barrier to weight loss over time (Sainsbury et al., 2019).

For this reason, the current study builds from and extends findings outlined in previous research concerning the impact of emotion dysregulation on poor physical and psychological outcomes and, specifically, deepening the relationship between emotional dysregulation, psychological distress, emotional eating, and BMI.

Material and methodsParticipants and proceduresA total convenience sample of 600 Italian young adults of the general population aged between 20 to 35 years was recruited for the study via Internet announcements delivered on online platforms (university communication systems, forums) and social media. Participants were asked to fill in an online survey using the Microsoft Azure platform, after being informed about the research and providing written informed consent. Italians, males and females, aged between 20 and 35 were included in the study. Data were collected from December 1st, 2020 to January 31st, 2021, as part of a larger research project named “Effects of the second wave COVID-19 on general population: sleep quality and hyperconnectivity” (Scarpelli et al., 2021).

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Center for Research and Psychological Intervention (CERIP) of the University of Messina (protocol number: 17758). All procedures were conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and its later advancements.

MeasuresAll the measurements were self-reported. We collected demographical data (sex, age, nationality, work status, marital status) and physical data (weight and height). Body Mass Index was obtained using the following formula: Kg/m2. For clinical data (emotion dysregulation, psychological distress, and emotional eating), participants completed the questionnaires described below.

Emotion dysregulationThe Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) (Gratz & Roemer, 2004) was administered to assess emotion dysregulation. The DERS is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 36 items, rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always), which explores the following subscales and a total score: Non-acceptance (DERS-NA), Goals (DERS-G), Impulse (DERS-I), Awareness (DERS-A), Strategies (DERS-S), and Clarity (DERS-C), which respectively concern non-acceptance of negative emotions, inability to undertake purposeful behavior when experiencing negative emotions, difficulty in controlling impulsive behavior when experiencing negative emotions, lack of awareness of one's emotions, limited access to effective emotion regulation strategies, lack of understanding of the nature of one's emotional responses. Higher scores indicate higher difficulties in emotion regulation. We used the Italian version validated by Giromini and colleagues (Giromini et al., 2012). In order to test whether the hypothesized measurement model fitted to our data, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted using a Maximum Likelihood estimator testing the structure of the questionnaire in our sample. The goodness of fit was assessed using the following indices: Non-significant Chi-square (χ2), normed Chi-square (ranged from 2 to 5), Comparative Fit Index (CFI ranged from 90 to 95 was considered acceptable, CFI of 0.95 or greater was considered desirable), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA ranged from 0.05 to 0.08 was considered acceptable and RMSEA of 0.05 or less, was considered desirable). In our sample the original Italian validated structure of the DERS showed inappropriate fit indices: (χ2=2414,841 p<.001, χ2/df =4.17; CFI=0.85 RMSEA=0.07; 90% CI= 0.067-0.073). Based on the analysis of the factor loadings and Modification Indices (MI) we applied changes in the original structure of the questionnaire. The resulted model showed better fit indices: (χ2=1724,605 p<.001, χ2/df =3.17; CFI=0.90 RMSEA=0.06; 90% CI=0.05-0.06). All the subscales and the total score of DERS, except for the Awareness subscale, showed good to excellent psychometric properties: Non-Acceptance: α= 0.88; Goals: α= 0.84; Impulse: α= 0.87; Awareness: α=0.39; Strategies: α= 0.90; Clarity: α= 0.83; Total score: α= 0.93.

Psychological distressThe Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21) (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1996) was administered to measure psychological distress. It is a self-report questionnaire composed of 21 items, rated on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 to 3, which explores three subscales and a total score: depression (DASS-D), anxiety (DASS-A), and stress (DASS-S). Higher scores indicate greater psychological distress. We used the Italian version validated by Bottesi and colleagues (Bottesi et al., 2015). In order to test whether the hypothesized measurement model fitted to our data, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted using a Maximum Likelihood estimator testing the structure of the questionnaire in our sample. In our sample the original Italian validated structure of the DASS-21 showed good fit indices: (χ2=763,720 p<.001, χ2/df =4.12; CFI=0.92 RMSEA=0.07; 90% CI=0.06-0.07). All the subscales and the total score of DASS-21 showed good to excellent psychometric properties: Depression: α= 0.90; Anxiety: α= 0.84; Stress: α= 0.90; Total score: α= 0.90.

Emotional eatingThe Emotional eating subscale of the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ-EE) (van Strien et al., 1986) was administered to assess emotional eating. The DEBQ is a self-report questionnaire used to detect eating behaviors. The Emotional Eating subscale consists of 13 items, rated on a 5-step Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (almost always). Higher scores indicate a higher level of emotional eating. We used the Italian version validated by Dakanalis and colleagues (Dakanalis et al., 2013). In order to test whether the hypothesized measurement model fitted to our data, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted using a Maximum Likelihood estimator testing the structure of the questionnaire in our sample. In our sample the original Italian validated structure of the DEBQ showed good fit indices: (χ2=1695,033 p<.001, χ2/df =3.48; CFI=0.91 RMSEA=0.06; 90% CI=0.061-0.068. The Emotional Eating subscale showed excellent psychometric properties: α= 0.95.

Statistical analysesDescriptive statistics were conducted to explore frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. The normal distribution of the variables was assessed considering indices of skewness and kurtosis of the variables. Parameters outside the limit of ± 2 for skewness and ±7 for kurtosis were considered as an index of non-normality (West et al., 1995). Pearson's correlations were performed for assessing associations between the main study variables.

We also conducted a path analysis to assess the relationships between emotional dysregulation (DERS), psychological distress (DASS-21), emotional eating (DEBQ-EE), and BMI using a Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimator.

The goodness of fit of the model was evaluated using Chi-square statistic (χ2), the Comparative Fit Indices (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Nonsignificant χ2, CFI and TLI values ≥ 0.95, SRMR values ≤ 0.08, and RMSEA values ≤ 0.06 were considered measures of good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Statistical significance was set to p<0.05.

We performed analyses using JASP [JASP Team (2020). JASP (Version 0.14.1) Computer software].

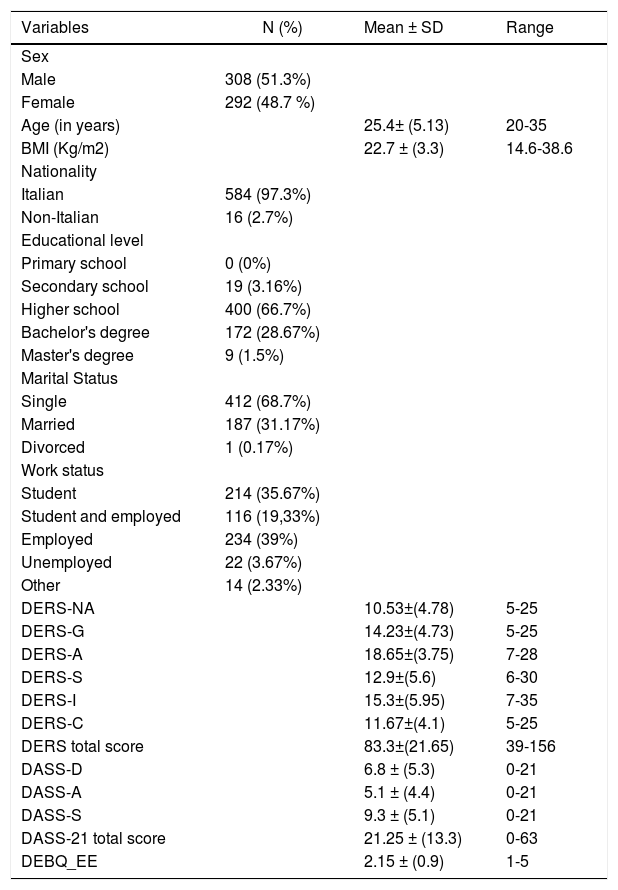

ResultsDescriptive statistics of the sampleThe sample was composed of 308 (51.3%) males and 292 (48.7%) females. The mean age was 25 (SD=5.13). Most of the participants were Italians (97,3%), had a high school degree (66,7%), were single (68,7%), and employed (39%).

According to the WHO criteria, 47 participants were considered underweight (BMI< 18.5), 437 had a healthy weight (18.5 ≤BMI≥25), and 116 were overweight (BMI>25). The group of underweight participants was composed of 40 (85.1%) males and 7 (14.9%) females. The mean of age was 23.2 (SD=4.9). The group of overweight participants was composed of 37 (31.9%) males and 79 (68.1%) females. The mean of age was 26.9 (SD=4.88). Finally, the group of healthy weight participants was composed of 215 (48.9%) males, 222 (51.1%) females. The mean of age was 25.1 (SD=5.11).

The descriptive statistics of the sample are shown in Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the sample.

Note: BMI: Body Mass Index;

DERS-NA: Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale-Non Acceptance subscale;

DERS-G: Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale-Goals subscale;

DERS-A: Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale-Awareness subscale;

DERS-S: Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale-Strategies;

DERS-I: Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale-Impulse subscale;

DERS-C: Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale-Clarity subscale;

DASS-D: Depression Anxiety and Stress scale-Depression subscale;

DASS-A: Depression Anxiety and Stress scale-Anxiety subscale;

DASS-S: Depression Anxiety and Stress scale-Stress subscale

DEBQ-EE: Dutch Eating Behaviors Questionnaire- Emotional eating subscale.

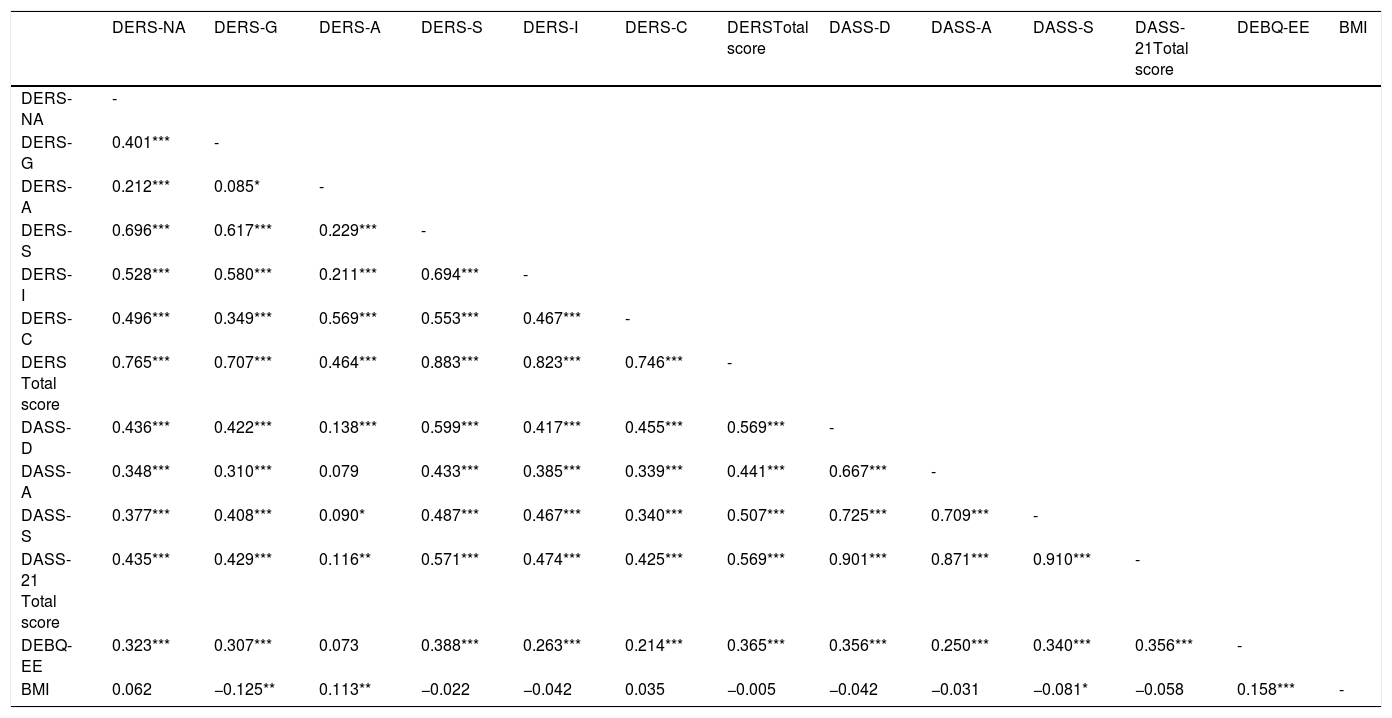

Correlations among the study variables.

Note: BMI: Body Mass Index; DERS-NA: Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale-Non Acceptance subscale; DERS-G: Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale-Goals subscale; DERS-A: Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale-Awareness subscale; DERS-S: Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale-Strategies; DERS-I: Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale-Impulse subscale; DERS-C: Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale-Clarity subscale; DASS-D: Depression Anxiety and Stress scale-Depression subscale; DASS-A: Depression Anxiety and Stress scale-Anxiety subscale; DASS-S: Depression Anxiety and Stress scale-Stress subscale; DEBQ-EE: Dutch Eating Behaviors Questionnaire- Emotional eating subscale.

Correlations among the main variables of interest showed a positive and significant relationship between DERS and DASS-21. Similarly, DERS was positively and significantly correlated with DEBQ-EE, with the only exception for the subscale Awareness (DERS-A) Significant correlations were found between DASS-21 and DEBQ-EE. BMI showed significant correlations with DEBQ-EE. Pearson's coefficients are shown in table 2.

The path modelThe path model was presented in Fig. 1. We tested a model in which DERS was hypothesized to be a significant predictor of DEBQ-EE and DASS-21; DASS-21 was supposed to be a predictor of DEBQ-EE. Finally, DEBQ-EE was considered a predictor of BMI.

The path model showed good indices of fit: χ2 (9.240; p=0.010), CFI (0.98), TLI (0.94), SRMR (0.04), RMSEA (0.07; 90% CI: 0.03-0.13). Specifically, DERS significantly predicted DEBQ-EE[b= 0.010; SE: 0.002; p=<0.001; 95% BC-CI (0.006–0.014)] and DASS-21[b= 0.348; SE: 0.020; p=<0.001; 95% BC-CI (0.306–0.387)] which in turn, significantly predicted DEBQ-EE[b= 0.015; SE: 0.003; p=<0.001; 95% BC-CI (0.008–0.022)]. Finally, DEBQ-EEwas the only significant contributor in predicting BMI [b= 0.0574; SE: 0.145; p=<0.001; 95% BC-CI (0.286–0.863)].

Since our sample was originally composed of underweight, normal weight, and overweight people, we have conducted additional analyses to test the same model in the three different specific subgroups. In the underweight subgroup (N=47) DERS significantly predicted DEBQ-EE[b= 0.019; SE: 0.005; p<0.001; 95% BC-CI (0.009–0.030)] and total score of DASS-21 [b= 0.031; SE: 0.064; p=<0.001; 95% BC-CI (0.207–0.456)], while total score of DASS-21 did not significantly predict DEBQ-EE [b = -0.010; SE: 0.010; p=<0.256; 95% BC-CI (-0.030–0.009)]. In addition, DEBQ-EE was not a significant contributor of BMI [b= 0.005; SE: 0.036; p=0.971; 95% BC-CI (-0.280–0.290)]. In the normal weight group (N=437) total score of DERS significantly predicted DEBQ-EE[b= 0.009; SE: 0.002; p<0.001; 95% BC-CI (0.004–0.013)] and total score of DASS-21[b= 0.339; SE: 0.024; p<0.001; 95% BC-CI (0.291–0.386)]. Total score of DASS-21 was a significant contributor of DEBQ-EE [b= 0.018; SE: 0.004; p<0.001; 95% BC-CI (0.011–0.025)]. Finally, DEBQ-EE did not significantly predict BMI [b= 0.040; SE: 0.092; p<0.665; 95% BC-CI (-0.140–0.219)]. In the third group of overweight people, total score of DERS was a significant predictor of DEBQ-EE [b= 0.011; SE: 0.005; p=0.017; 95% BC-CI (0.002–0.020)] and total score of DASS-21 [b= 0.387; SE: 0.047; p<0.001; 95% BC-CI (0.294–0.479)]. Total score of DASS-21 was a significant predictor of DEBQ-EE [b= 0.015; SE: 0.007; p=0.036; 95% BC-CI (0.000973–0.030)]. Finally, DEBQ-EE did not significantly predict BMI [b= 0.166; SE: 0.251; p=0.508; 95% BC-CI (-0.325–0.657)].

DiscussionThe current study was aimed to investigate the impact of emotion dysregulation on emotional eating, psychological distress, and BMI in a sample of Italian young adults. As expected, we found significant associations between all the study variables. In particular, we found significant associations between emotion dysregulation, psychological distress, emotional eating, and BMI. As expected, emotion dysregulation was found to be a significant factor in predicting levels of psychological distress and emotional eating. In addition, emotional eating was found to be a predictor of BMI. These findings were in line with previous studies, which suggested that difficulties in emotion regulation strategies were linked to greater perceived psychological distress (Abdi & Pak, 2019; Aldea & Rice, 2006; Kirwan et al., 2017; Squires et al., 2020) and emotional eating (Casagrande et al., 2020; McAtamney et al., 2021). Such results have been confirmed during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to Cecchetto and colleagues (Cecchetto et al., 2021), in Italy, there was an increase of emotional eating during lockdown that was predicted by increased levels of psychological distress, in particular anxiety and depression as well as poorer quality of relationships and quality of life.

Emotional eating was not only associated with poorer psychological outcomes but also with physical ones since it was found to be related to greater consumption of high energy-density food (Pinaquy et al., 2003a) and increased BMI (Casagrande et al., 2020). In our study, the association between emotional eating and BMI was confirmed, suggesting that the higher the level of emotional eating, the greater BMI.

Such evidence offers important clinical implications. First of all, our work exceeds the limits of previous research by exploring the link between emotion dysregulation and physical outcomes – as BMI – in addition to the psychological ones, which have been already studied. Furthermore, by elucidating the role of emotion dysregulation on physical and psychological outcomes and specifically highlighting the impact of emotion dysregulation on disordered eating, our findings could inform the development and implementation of psychological interventions aimed at promoting psychological well-being and weight loss by focusing on the promotion of emotion regulation strategies, in order to reduce emotional eating.

The present study is not free of limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study cannot support causal conclusions. In addition, we involved a convenience sample of young adults from the general population in which participants have been included in the study on the basis of their willingness to participate. Even though a convenience sample is easy and affordable, it may not be representative of the population. Another limitation concerns the lack of clinical instruments aimed at assessing for possible eating disorders among participants..

Then, for our assessment, we only used self-report measures that could be affected by biases. In this regard, a recent study on emotional eating suggested that retrospective emotional eating, investigated via self-report forms is a different construct of momentary emotional eating assessed with innovative methodologies such as the Ecological Momentary Assessment (Chwyl et al., 2021). Direct, instead of retrospective measures could be free from biases such as one's current emotional state and provide an objectively assess the intended construct. Finally, quite small relations were found, suggesting that there could be additional factors we did not consider in our study that need to be addressed in future replications of the research such as alexithymia (Aldea & Rice, 2006; Kirwan et al., 2017) and interoceptive awareness (Spinosa et al., 2019). Future research should cover additional constructs, involve other measurement strategies, and test the same model in different subgroups (i.e., with eating disorders).

ConclusionsTo sum up, our findings provide new additional evidence that how emotions are regulated influences eating behaviors. The results suggest emphasis in interventions to reduce emotional eating need to be placed on addressing functional emotion regulation strategies. Various psychological interventions, including mindfulness and acceptance-based interventions, have been examined for their effectiveness in emotion dysregulation. In particular, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) includes a combination of acceptance, mindfulness, and behavior-change methods. ACT can be useful in helping people learn to be open to uncomfortable internal experiences, instead of reacting to them as in the case of emotional eating.

FundingThis work was supported by “Ricerca Corrente” funding from Italian Ministry of Health to IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano.