The three-item Sexual Distress Scale (SDS-3) has been frequently used to assess distress related to sexuality in public health surveys and research on sexual wellbeing. However, its psychometric properties and measurement invariance across cultural, gender and sexual subgroups have not yet been examined. This multinational study aimed to validate the SDS-3 and test its psychometric properties, including measurement invariance across language, country, gender identity, and sexual orientation groups.

MethodsWe used global survey data from 82,243 individuals (Mean age=32.39 years; 40.3 % men, 57.0 % women, 2.8 % non-binary, and 0.6 % other genders) participating in the International Sexual Survey (ISS; https://internationalsexsurvey.org/) across 42 countries and 26 languages. Participants completed the SDS-3, as well as questions regarding sociodemographic characteristics, including gender identity and sexual orientation.

ResultsConfirmatory factor analysis (CFA) supported a unidimensional factor structure for the SDS-3, and multi-group CFA (MGCFA) suggested that this factor structure was invariant across countries, languages, gender identities, and sexual orientations. Cronbach's α for the unidimensional score was 0.83 (range between 0.76 and 0.89), and McDonald's ω was 0.84 (range between 0.76 and 0.90). Participants who did not experience sexual problems had significantly lower SDS-3 total scores (M = 2.99; SD=2.54) compared to those who reported sexual problems (M = 5.60; SD=3.00), with a large effect size (Cohen's d = 1.01 [95 % CI=-1.03, -0.98]; p < 0.001).

ConclusionThe SDS-3 has a unidimensional factor structure and appears to be valid and reliable for measuring sexual distress among individuals from different countries, gender identities, and sexual orientations.

Sexual health is an essential dimension of global health (McCabe et al., 2010; Mitchell et al., 2021), and its importance has been widely acknowledged (Alimoradi et al., 2022; Masoudi et al., 2022; Varghese et al., 2022). Sexual pleasure, rights, and wellbeing are important factors contributing to achieving a satisfying sex life (Mitchell et al., 2021). Moreover, it is advocated that these four factors (sexual health, pleasure, rights, and wellbeing) should be simultaneously considered for public health promotion (Mitchell et al., 2021). Yet, it is difficult to promote a satisfying sex life from a public health perspective and simultaneously consider the four factors because sexuality is a complex issue. Indeed, healthcare providers may experience barriers and difficulties when treating sexuality-related problems (Lin, Fung et al., 2017, 2017; Lin et al., 2019). Therefore, there is a need to help healthcare providers assist individuals in pursuing sexual health and wellbeing (Mitchell et al., 2021).

According to a previous meta-analysis, psychological distress and sexual functioning may reciprocally influence each other (Atlantis & Sullivan, 2012). Persons with sexual dysfunction were more likely to be emotionally distressed, and those with depressive features may have increased likelihood of reporting sexual dysfunction (Atlantis & Sullivan, 2012). This indicates that sexual distress is an important research topic because it associates with individuals’ general mental health conditions (Mitchell et al., 2021; Nowosielski et al., 2013; Tavares et al., 2022). Moreover, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) indicates that sexual distress is a prerequisite for clinicians to diagnose an individual with sexual dysfunction (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Thus, a valid and reliable assessment of sexual distress is essential (Ishak & Tobia, 2013). Given that clinical settings are usually busy, and clinicians may not have sufficient time to meet every patient to ask them detailed information concerning sexual distress, a brief instrument with strong psychometric properties measuring sexual distress is warranted.

Several measures of sexual distress are currently available to researchers and clinicians (Santos-Iglesias et al., 2018a). Among the instruments assessing sexual distress, one widely used tool is the 12-item Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS) (Derogatis et al., 2002), assessing global sexual distress. Although the FSDS was initially developed to evaluate women's sexual distress, the items of the FSDS are gender-neutral and have also been validated among men (Santos-Iglesias et al., 2018b). Therefore, prior revised versions have been proposed to enhance its utility, extending its use to specific conditions related to low sexual desire (Derogatis et al., 2008) or cancer survival (Santos-Iglesias et al., 2020), or by shortening the scale to reduce respondent burden (e.g., a three-item version of the Sexual Distress Scale [SDS-3] [Pâquet et al., 2018], or a five-item version of the Sexual Distress Scale [SDS-SF] [Santos-Iglesias et al., 2020]).

Although the SDS-SF was found to be robust in its psychometric properties and has been examined using different psychometric testing methods, the SDS-3 has fewer items than the SDS-SF (three items vs. five items). Even though the three-item (i.e., SDS-3) and five-item (i.e., SDS-SF) versions of the scale do not have big differences in the number of items, it may be a crucial point for studies in busy clinical settings and large-scale surveys. In addition, large-scale surveys may want to assess various concepts, and thus want to use the shortest possible version of an instrument for the sake of parsimony. For example, when using the SDS-3 with the two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (Kroenke et al., 2003), two concepts (i.e., sexual distress and depression) could be simultaneously assessed in less than one or two minutes. In contrast, if using the SDS-SF, five items can only assess one concept of sexual distress.

To the best of the present authors’ knowledge, only three versions associated with the FSDS are available in the literature: the original 12-item FSDS (Derogatis et al., 2002), the five-item SDS-SF (Santos-Iglesias et al., 2020), and the three-item SDS-3 (Pâquet et al., 2018). The three items selected in the SDS-3 are those that correlated the most with the global score and thus may provide more comprehensive and correlational measurement. The internal consistency of the SDS-3 was reliable for the surveyed women (Cronbach α = 0.88) and their partners (Cronbach α =0.89) in the original sample (Pâquet et al., 2018). Although Pâquet et al. (2018) has shortened the FSDS to the SDS-3 to decrease the burden of survey completion for participants and provided preliminary psychometric evidence for the SDS-3, they did not rigorously evaluate its psychometric properties. Moreover, to the best of the present authors’ knowledge, the SDS-3 has never been tested for its psychometric properties and could prove more useful for clinicians as well as for research requiring brief measures. Therefore, the present study focused on the SDS-3.

The original and revised versions of the FSDS have also been translated into several languages and used across different populations and cultures (Azimi Nekoo et al., 2014; Bae et al., 2006; Nowosielski et al., 2013; Tavares et al., 2022). However, most of the evidence concerning sexual distress is derived from prior research conducted in Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) nations, neglecting the inclusion of non-English speaking countries and sexual and gender diverse groups (Klein et al., 2022). Hence, we know little about how to measure sexual distress in under-represented populations. In addition, measurement invariance remains untested for any versions of the SDS (or FSDS). Without thorough measurement invariance testing, measurement biases may be present when comparing groups from different cultures, potentially leading to invalid comparisons and inaccurate implications (Klein et al., 2022). Thus, it is necessary to thoroughly test the psychometric properties of the SDS-3 to further high-quality research on sexual distress across cultural, gender and sexual identities.

Therefore, the present study aimed to validate the SDS-3 and test its psychometric properties, including measurement invariance across language, country, gender identity, and sexual orientation groups. Moreover, we tested the known-group validity of the SDS-3 via one general item assessing sexual health problems, given the hypothesis that individuals with self-reported sexual health problems are more likely to be distressed than their counterparts without sexual problems (Bőthe et al., 2021a).

MethodsProcedureThe International Sex Survey (ISS) is a cross-sectional and self-report online survey (for detailed information on the ISS study design, see [Bőthe et al., 2021a)]) involving 42 countries. In brief, using the guidelines proposed by Beaton et al. (2000), the English survey battery was translated into 25 additional languages across 42 countries before data collection (Bőthe et al., 2021a). Data were collected between October 2021 and May 2022 via convenience sampling. The data collection was completed via the following methods for dissemination and promotion: (i) popular news websites; (ii) the collaborators’ local research network; and (iii) advertisements on social media. In addition, a donation of 50 cents (with a maximum of 1000 USD) to a nonprofit organization was made for every completed questionnaire regardless of participants’ country of residence. All collaborating countries followed detailed guidelines about the translation procedure and the recruitment of participants (see Bőthe et al., 2021a). Supplementary A provides further information on the study procedure.

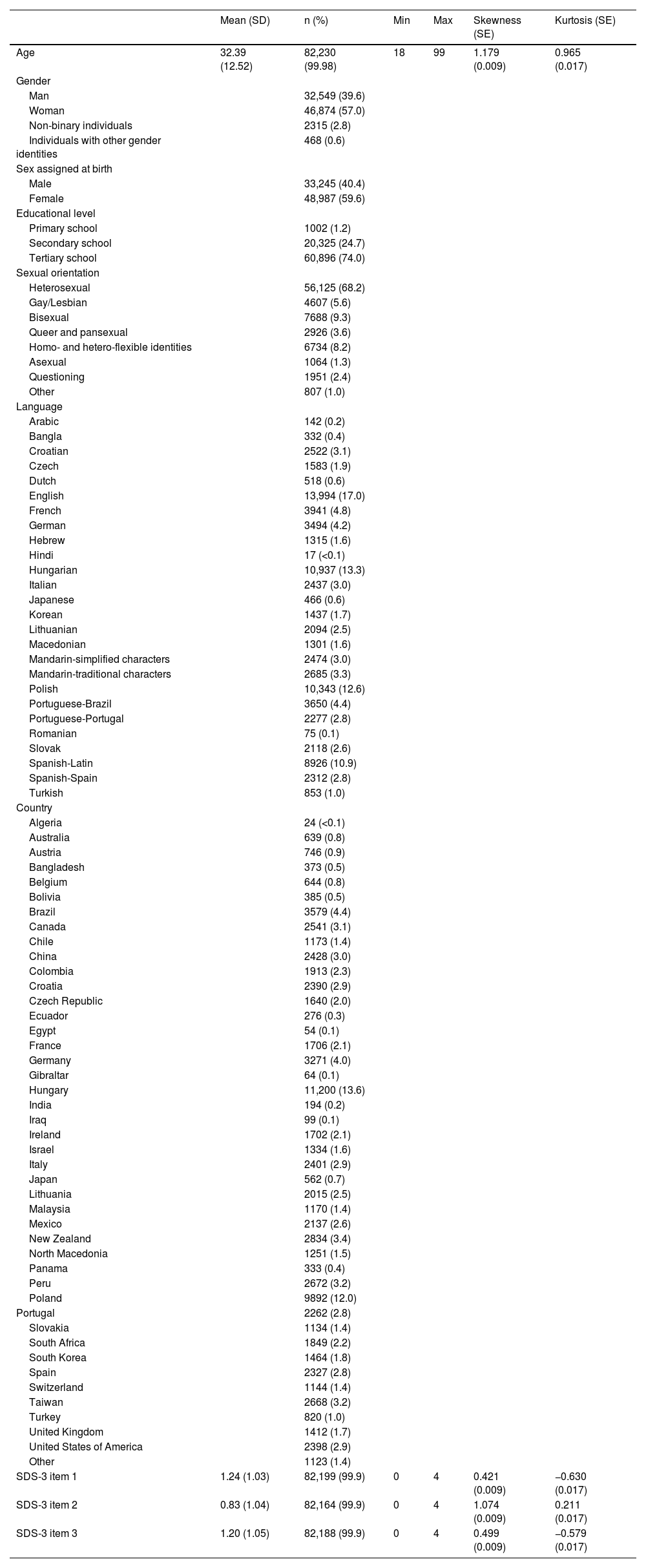

ParticipantsParticipants who gave informed consent completed the survey battery via the Qualtrics online platform. The time to complete the ISS was approximately 25 to 45 minutes, and the survey was conducted anonymously. As described in the preregistered analytic plan (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/DK78R), a total of 215,252 people online clicked the ISS survey link, and the following individuals were excluded from the final analyses: 40,331 individuals quit before entering the informed consent page, 2178 did not consent to participate, 441 were under 18 years, 26,558 did not report their age, 57,372 quit the survey before completing the attention testing questions, 5735 did not pass the attention testing questions, and 394 provided unengaged answers (e.g., the length of romantic relationship was longer than reported age). Hence, data from 82,243 participants (mean [SD] age = 32.39 [12.52]; 39.6 % men, 57.0 % women, and 3.4 % others) were included in the final sample of the ISS. Table 1 presents the sample's detailed sociodemographic characteristics. Participants’ sociodemographic characteristics by country is available at https://osf.io/n3k2c/?view_only=838146f6027c4e6bb68371d9d14220b5.

Participant characteristics and descriptive statistics for the Short version of the Sexual Distress Scale (SDS-3) (N = 82,243).

Note. SDS-3 = Short version of the Sexual Distress Scale.

Three five-point Likert-scale items (0=never; 4=always) were used to assess sexual distress: How often did you feel (1) distressed about your sex life?; (2) inferior because of sexual problems?; and (3) worried about sex? (Pâquet et al., 2018). Higher SDS-3 scores reflect higher levels of sexual distress. The translation of the SDS-3 in all available languages is available at https://osf.io/jcz96/?view_only %20= %209af0068dde81488db54638a01c8ae118.

Self-report sexual problemsOne item was used to ask about sexual problems: “Do you suffer from any sexual problems?” with the response options of “Yes” or “No.” There were no definitions or examples of sexual problems given alongside the item.

Background informationThe participants’ demographics includes their age, gender (man, woman, non-binary, or others), biological sex (male or female), educational level (primary school, secondary school, or tertiary school), and sexual orientation (heterosexual, gay/lesbian, bisexual, queer and pansexual, homo- and hetero-flexible identities, asexual, questioning, or other), among other variables (Bőthe et al., 2021a).

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis followed the preregistered analytic plan (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/DK78R), which includes descriptive statistics (using IBM SPSS), testing of dimensionality (i.e., confirmatory factor analysis [CFA] using the lavaan package in R software), measurement invariance (using the lavaan package in R software), reliability (using the psych package in R software), and known-group validity (using the effectsize package in R software). Supplementary B provides detailed information regarding all statistical analyses.

Normality checks, unidimensionality and internal consistency testsSkewness lower than three and kurtosis lower than 10 were used to evaluate normality (Kline, 2023). CFA with a diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS) estimator was used to handle the ordered-categorical items of the SDS-3 (Finney & DiStefano, 2006). Comparative fit index (CFI) higher than 0.9; Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) higher than 0.9; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) lower than 0.08; and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) lower than 0.08 were used to assess CFA fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1992). However, given that the SDS-3 has only three items and a unidimensional factor structure, the CFA could result in a saturated model, and the fit indices could be expected to be perfect or close to perfect (i.e., CFI and TLI = 1.000; RMSEA and SRMR = 0.000). Therefore, factor loadings were examined to see if the three SDS-3 items loaded onto the same factor, with expected factor loadings higher than 0.3 (Field, 2013). For Cronbach's α and McDonald's ω, values higher than 0.7 were expected to indicate acceptable internal consistency (Yepes-Nunez et al., 2021). Corrected item-total correlations were calculated and were expected to be higher than 0.3 (del Mar Pozo-Balado et al., 2016).

Measurement invariance testMulti-group CFA with a DWLS estimator was used to examine the measurement invariance of the SDS-3. Four variables (language [23 subgroups], country [33 subgroups], gender identity [three subgroups], and sexual orientation [eight subgroups]) were used for the multi-group CFA to test measurement invariance. In the multi-group CFA, a minimum of 300 participants were required for each subgroup based on Monte Carlo simulations with average factor loadings and residual variances obtained from two prior studies (Derogatis et al., 2002; Pâquet et al., 2018). Nested models were compared to examine the level of measurement invariance, including configural invariance (Model 0; a baseline model assuming equivalent factor structure across subgroups), metric invariance (Model 1; a model with factor loadings constrained to be equal across subgroups), scalar invariance (Model 2; a model with factor loadings and item intercepts constrained to be equal across subgroups), and residual invariance (Model 3; a model with factor loadings, item intercepts, and residuals constrained to be equal across subgroups).

Full invariance was first examined: When ΔCFI higher than −0.010, ΔTLI higher than −0.010, ΔRMSEA lower than 0.015 (for scalar and residual invariance) or lower than 0.03 (for metric invariance), and ΔSRMR lower than 0.03, the level of measurement invariance was achieved (Chen, 2007; Cheung & Rensvold, 2002; Rutkowski & Svetina, 2014). If the full invariance was not achieved, we examined partial invariance (Milfont & Fischer, 2010). Specifically, partial invariance indicates that at least two items are invariant for each level (i.e., metric, scalar, and residual invariance) across subgroups (Byrne et al., 1989). Moreover, we relaxed the item being the most non-invariant across subgroup (i.e., relaxing the item could achieve the best improvement of model fit). Afterwards, latent means between the subgroups were compared using the reference group approach (Gil-Monte et al., 2023; Muthén & Asparouhov, 2018; Sawicki et al., 2022).

Known-group validity testIndependent t-tests with Cohen's d (0.2 as small; 0.5 as moderate; and 0.8 as large) (Cohen, 2013) were used to examine the known-group validity of the SDS-3 between people reporting and not reporting sexual problems.

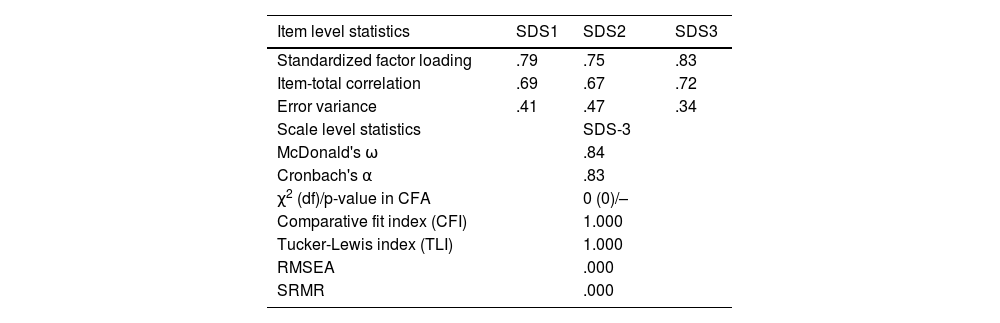

ResultsTable 2 presents the CFA results (n = 82,136). Detailed information about the internal consistency by language is reported in Supplementary Table S1. Measurement invariance was tested across languages (n = 332 [Bangla], 2552 [Croatian], 1583 [Czech], 518 [Dutch], 13,994 [English], 3942 [French], 3494 [German], 1315 [Hebrew], 10,937 [Hungarian], 2437 [Italian], 466 [Japanese], 1437 [Korean], 2094 [Lithuanian], 1301 [Macedonian], 2474 [Mandarin-simplified characters], 2685 [Mandarin-traditional characters], 10,343 [Polish], 3650 [Portuguese-Brazil], 2277 [Portuguese-Portugal], 2118 [Slovak], 8926 [Spanish-Latin], 2312 [Spanish-Spain], and 853 [Turkish]), countries (n = 639 [Australia], 746 [Austria], 373 [Bangladesh], 644 [Belgium], 385 [Bolivia], 2541 [Canada], 1173 [Chile], 2428 [China], 1913 [Colombia], 2390 [Croatia], 1640 [Czech Republic], 3271 [Germany], 11,200 [Hungary], 1702 [Ireland], 1334 [Israel], 2401 [Italy], 562 [Japan], 1170 [Malaysia], 2137 [Mexico], 2834 [New Zealand], 1251 [North Macedonia], 333 [Panama], 2672 [Peru], 9892 [Poland], 1134 [Slovakia], 1849 [South Africa], 1464 [South Korea], 2327 [Spain], 2668 [Taiwan], 820 [Turkey], 1412 [United Kingdom], 2398 [United States of America], and 1123 [other]), gender identities (n = 32,549 [man], 46,874 [woman], and 2783 [non-binary or with other gender identities]) and sexual orientations (n = 56,125 [heterosexual], 4607 [gay/lesbian], 7688 [bisexual], 2926 [queer and pansexual], 6734 [homo- and hetero-flexible identities], 1064 [asexual], 1951 [questioning], and 807 [other]) using the unidimensional structure (Table 3).

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and internal consistency results of the Short version of the Sexual Distress Scale (SDS-3) (N = 82,136).

Notes. SDS-3 = Short version of the Sexual Distress Scale; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; SRMR = standardized root mean square residual. The SDS-3′s factor structure is a just-identified model; therefore, the degree of freedom is 0 and all the fit indices were at perfect levels.

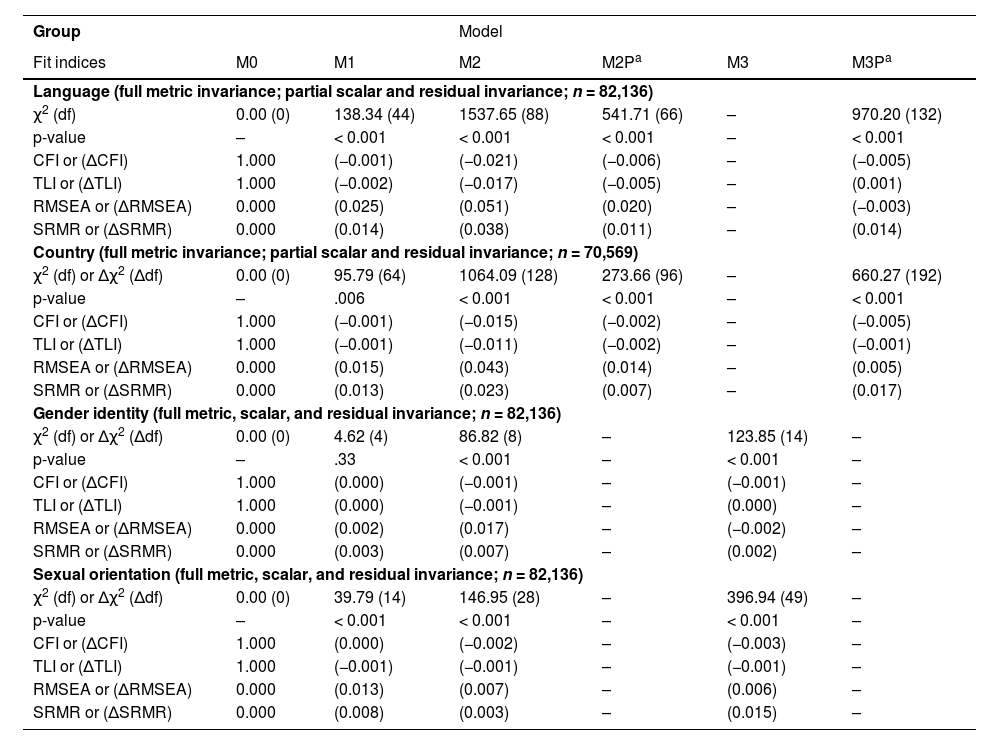

Measurement invariance of the Short version of the Sexual Distress Scale (SDS-3).

a Relaxed the item intercept and uniqueness for SDS1 for language-based measurement invariance testing.

Notes. CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; SRMR = standardized root mean square residual. M0 = configural model; M1 = model with factor loadings constrained equal across subgroups (i.e., metric invariance); M2 = model with factor loadings and item intercepts constrained equal across subgroups (i.e., scalar invariance); M2P = M2 with relaxed items in intercept across subgroups (i.e., partial scalar invariance); M3 = model with factor loadings, item intercepts, and residual constrained equal across subgroups (i.e., residual invariance); M3P = M3 with relaxed items in intercept and uniqueness across subgroups (i.e., partial residual invariance).

For the language-based measurement invariance tests, those languages with a sample size < 300 were excluded from the present analysis (Arabic n = 142; Hindi n = 17; and Romanian n = 75). For the country-based measurement invariance tests, 33 countries were tested (please refer Supplementary Table S2 for details regarding which 33 countries were tested). For the gender identity-based measurement invariance tests, participants were regrouped into three categories (man, woman, and gender diverse individual). For the sexual orientation-based measurement invariance tests, participants were regrouped into eight categories (heterosexual, gay/lesbian, bisexual, queer and pansexual, homo- and hetero-flexible identities, asexual, questioning, and other).

Full invariance at the metric invariance level was supported across all languages (n = 82,136), countries (n = 70,569), gender identities (n = 82,136), and sexual orientations (n = 82,136). Full scalar and residual invariance levels were supported across gender identities and sexual orientations, but not across languages and countries. The first item of the SDS-3 was then relaxed across language and country subgroups to examine whether the SDS-3 was partially scalar invariant (for item intercepts) and residual invariant (for item intercepts and corresponding uniqueness). The fit indices supported the partial invariance for the SDS-3 across language subgroups for both scalar and residual invariance.

Supplementary Table S2 provides the latent mean and observed mean comparisons across the subgroups, with the numbers of participants the same as those for the measurement invariance tests described above. In sum, as compared with participants from Australia (latent mean as 0; observed mean as 3.41), participants from the following countries showed relatively lower levels of sexual distress with small effect sizes (i.e., Cohen's d > 0.2): China (latent mean: −0.242; observed mean: 2.64), Colombia (latent mean: −0.302; observed mean: 2.65), Czech Republic (latent mean: −0.352; observed mean: 2.36), Germany (latent mean: −0.243; observed mean: 2.74), Israel (latent mean: −0.245; observed mean: 2.88), Japan (latent mean: −0.336; observed mean: 2.30), and Taiwan (latent mean: −0.222; observed mean: 2.59). Moreover, participants from Spain had the highest levels of sexual distress (latent mean: 0.120; observed mean: 3.79).

The SDS-3 was then examined for known-group validity using the item assessing self-report sexual problems. Participants who did not suffer from sexual problems had significantly lower SDS-3 total scores (M [SD] = 2.99 [2.54]) compared to those who reported sexual problems (M [SD] = 5.60 [3.00]), with a large effect size (Cohen's d [95 % CI] = 1.01 [−1.03, −0.98]; p < 0.001).

DiscussionThe present study examined the psychometric properties of the SDS-3 (Pâquet et al., 2018), a three-item scale assessing sexual distress, across countries, languages, gender identities, and sexual orientations. The psychometric findings support the use of the SDS-3 across these groups. Results of the present study contribute to the literature by providing a brief, validated instrument that can accurately assess sexual distress across multiple populations, including underserved and underrepresented communities.

Previously, Pâquet et al. (2018) developed the SDS-3 by selecting three items from the original FSDS, and they found that SDS-3 scores strongly and positively correlated well with FSDS scores. However, they did not thoroughly investigate the psychometric properties of the SDS-3, potentially due to sample constraints. In this study, we provided evidence for a unifactorial structure for the SDS-3, which is consistent with the original FSDS’ factor structure (Derogatis et al., 2002; Santos-Iglesias et al., 2018b). Moreover, per calls for the FSDS to be applied to populations other than women (Derogatis et al., 2002; Santos-Iglesias et al., 2018b), the SDS-3 had a consistent and invariant unidimensional structure across gender identities. Moreover, findings extend the robustness of the SDS-3 to non-WEIRD populations and individuals with diverse sexual orientations as well.

The internal consistency of the SDS-3 in this global study was acceptable (e.g., all language versions had both Cronbach's α and McDonald's ω higher than 0.7). Moreover, measurement invariance testing across subgroups suggested that the SDS-3 items were interpreted similarly across subgroups, with results supporting full invariance across countries, gender identities, and sexual orientations. However, the first item of feeling distressed about one's sexual life was only partially invariant across languages and countries. Whether cultural differences underlying different languages could explain potential differences in perceptions of this item requires further research consideration, and future studies using qualitative methods to explore the interpretation of “distress” across cultures are warranted. Nevertheless, partial invariance is still acceptable given the many groups used for measurement invariance testing (Muthén & Asparouhov, 2018; Putnick & Bornstein, 2016). Therefore, we tentatively conclude that using SDS-3 across different languages and countries may not generate serious assessment problems, but this partial invariance should still be carefully considered.

We considered that culture may underlie the non-invariant findings for languages and countries. Therefore, potential differences in perceptions of sexual distress across languages/countries require further consideration. In this regard, future studies are warranted and could use qualitative methods exploring the interpretation of "sexual distress" across cultures. Nevertheless, the evidence for full measurement invariance from the present study suggests that the SDS-3 could be used without potential biases of different interpretations due to a respondent's gender identity or sexual orientation. In this regard, researchers in the field of sexuality and practitioners addressing sexual distress issues may use the SDS-3 when assessing people with diverse gender identities or sexual orientations. Subsequently, meaningful comparisons (if needed) of sexual distress across people with different gender identities or sexual orientations may be obtained using the SDS-3. In terms of different languages or countries, special attention to its item 1 may be needed because different item intercepts across languages/countries were observed. Therefore, it is better to use latent means instead of observed means from the SDS-3 for language/country comparisons. However, given that partial invariance of the SDS-3 was supported, using the SDS-3 observed summed scores may not generate serious problems when comparing sexual distress between languages or countries. In sum, from clinical and research perspectives, having supportive evidence for measurement invariance may contribute to more precise communication about sexual distress based on commonly used valid screening tools.

In the known-group validity testing, those who reported suffering from sexual problems had higher levels of sexual distress than those who did not suffer from sexual problems. This finding provides preliminary evidence for the known-group validity of the SDS-3 and corroborates prior findings showing that people with sexual problems or dysfunctions had higher levels of sexual distress than those without these issues (Bőthe et al., 2021b). However, given that the question on sexual problems used in the present study was general and not specific, it is unclear what types of sexual problems were associated with the higher SDS-3 scores. Therefore, additional studies using specific questions and validated instruments of sexual problems (e.g., Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale [Varney et al., 2023]) are warranted.

Strengths and limitationsIn this international study, we validated the SDS-3 using a large multi-national sample across various countries, with an effort to recruit participants from different social backgrounds and with diverse sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., diverse gender identities) (Klein et al., 2022). The general limitations of the ISS are discussed on the study's OSF page (https://osf.io/n3k2c/?view_only=838146f6027c4e6bb68371d9d14220b5). Briefly, these limitations include the following. First, the data were collected using an online survey with self-reports; thus, participants were not representative of each country's population and the findings are vulnerable to biases (e.g., recall or social desirability bias). Second, different promotion methods were used in different countries, which may have generated different levels of motivation for participants to complete the survey in dofferent countries. Third, it was not possible to recruit enough participants for each country to be included in all steps of the data analysis. Additionally, the known-group validity of the present study was not assessed using a validated external criterion measure but only a general question (i.e., Do you suffer from any sexual problems?). Although a large effect size was observed in the general question indicating good known-group validity of the SDS-3, future studies are also needed to use standardized and validated instruments to reevaluate the known-group validity of the SDS-3. Moreover, given that the question was asked without definitions or examples, respondents may have conceptualized “sexual problems” differently, especially across countries/cultures. Second, other forms of psychometric testing (e.g., involving relationships to other variables, sensitivity to change, test-retest reliability) were not examined in the present study. Future studies should further examine the psychometric properties of the SDS-3. Lastly, the present sample was recruited from the general population, thus restricting the generalizability to those with clinical levels of sexual problems. Further studies are needed to corroborate and extend our findings, especially using longitudinal designs and in other populations (e.g., adolescents, older adults).

ConclusionThe present study showed preliminary evidence for the psychometric properties for the SDS-3. Specifically, the present study showed that the SDS-3 is a unifactorial instrument with measurement invariance across individuals from different countries, languages, gender identities, and sexual orientations. Known-group validity further corroborated that those reporting sexual problems had higher SDS-3 scores than their counterparts without sexual problems. Obtaining evidence on measurement invariance across groups, especially language subgroups in the present study, is important when between-group comparisons are conducted. The results suggest that using the SDS-3 across different languages may not result in serious assessment biases, which may help synthesize the results derived from each participating site and delineate the roles of cultural factors in sexual distress. Although we recommend using the SDS-3 in large-scale epidemiological surveys with diverse populations to understand the prevalence of sexual distress throughout the lifespan, future studies are needed to provide further information on other important psychometric properties of the SDS-3 (e.g., convergent validity).

Ethical approvalThe authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the relevant national and institutional committees’ ethical standards on human experimentation and the Helsinki Declaration. The study was approved by all collaborating countries’ national/institutional ethics review boards: https://osf.io/n3k2c/?view_only=838146f6027c4e6bb68371d9d14220b5

Informed consentAll participants gave informed consent when completing the ISS survey battery via an online platform (i.e., Qualtrics Research Suite).

Availability of data and material (data transparency)All published papers and conference presentations using the ISS dataset are available for public viewing on the related OSF pages:

- 1)

Publications: https://osf.io/jb6ey/?view_only=0014d87bb2b546f7a2693543389b934d;

- 2)

Conference presentations: https://osf.io/c695n/?view_only=7cae32e642b54d049e600ceb8971053e.

The study design, including the preregistered study protocol, can be found at https://osf.io/uyfra/?view_only=6e4f96b748be42d99363d58e32d511b8.

Detailed data cleaning procedure: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/DK78R

The wording of each question and answer option in all languages can be seen at https://osf.io/jcz96/?view_only=9af0068dde81488db54638a01c8ae118.

The translation of the measures in this study can be found at the following link in all available languages: https://osf.io/jcz96/?view_only=9af0068dde81488db54638a01c8ae118.

Preregistered analysis plan: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/DK78R

Detailed information of Monte Carlo simulations: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/DK78R

Detailed information of grouping in the statistical analysis can be found at: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/DK78R

Detailed sociodemographic characteristics by country can be found at https://osf.io/n3k2c/?view_only=838146f6027c4e6bb68371d9d14220b5.

Code availabilityNot applicable

Chung-Ying Lin was supported by the WUN Research Development Fund (RDF) 2021 and the Higher Education Sprout Project, the Ministry of Education at the Headquarters of University Advancement at the National Cheng Kung University (NCKU), Tainan, Taiwan; Mónika Koós and Léna Nagy were both supported by the ÚNKP-22–3 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund; Mateusz Gola was supported by National Science Centre of Poland (Grant No.: 2021/40/Q/HS6/00219); Shane W. Kraus was supported by the Kindbridge Research Institute; Lijun Chen was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No.: 19BSH117); Zsolt Demetrovics was supported by the Hungarian National Research, Development, and Innovation Office (Grant No.: KKP126835); Rita I. Csako was supported by Auckland University of Technology, 2021 Faculty Research Development Fund; Roman Gabrhelík was supported by the Charles University institutional support programme Cooperatio (Health Sciences); Hironobu Fujiwara was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Transformative Research Areas (A) (Japan Society for The Promotion of Science, JP21H05173), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (Japan Society for The Promotion of Science, 21H02849), and the smoking research foundation; Karol Lewczuk was supported by Sonatina grant awarded by National Science Centre, Poland (Grant No.: 2020/36/C/HS6/00005); Christine Lochner received support from the WUN Research Development Fund (RDF) 2021; Gábor Orosz was supported by the ANR grant of the Chaire Professeur Junior of Artois University and by the Strategic Dialogue and Management Scholarship (Phase 1 and 2); Sungkyunkwan University's research team was supported by Brain Korea 21 (BK21) program of National Research Foundation of Korea; Gabriel C. Quintero Garzola was supported by the SNI #073–2022 (SENACYT, Rep. of Panama); Kévin Rigaud was supported by a funding from the Hauts-de-France region (France) called “Dialogue Stratégique de Gestion 2 (DSG2)”; Sophie Bergeron was supported by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair; Beáta Bőthe was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the SCOUP Team – Sexuality and Couples – Fonds de recherche du Québec, Société et Culture and by the Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship (Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, SSHRC) during the preparation of the first draft of the manuscript.