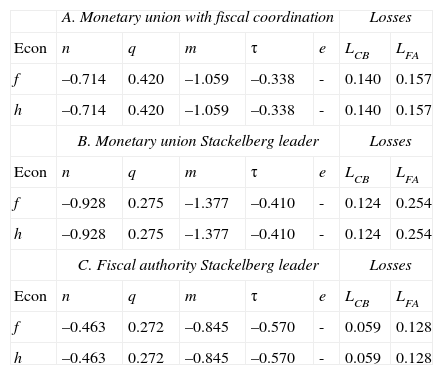

Motivated by the recent experience of Greece and other relatively small European Monetary Union members, this paper examines the appeal of taking part in a large monetary union from the perspective of small open economies. We show that in the absence of fiscal policy considerations, taking part in a large monetary union is counterproductive for a small economy. Nevertheless, once the role of fiscal policy is properly incorporated, taking part in the monetary union becomes desirable from a social perspective. Following these results, we explore the prospects of engaging both economies in fiscal coordination and on how different schemes of policy synchronization can provide the grounds to make cooperation beneficial for the members of a monetary union. We find that when monetary and fiscal authorities cooperate and attempt to exploit externalities for their own benefit, a Pareto efficient outcome can be achieved if fiscal policy in the monetary union is coordinated by a central authority and such authority acts as a the Stackelberg leader vis-à-vis the central bank. Our analysis suggests that this regime is superior to (i) a monetary union in which fiscal authorities conduct their policy in an independent or (ii) coordinated fashion, (iii) a regime where both authorities internalize the effects of their own externalities by allowing the central bank to act as Stackelberg leader and (iv) a regime in which the small open economy decides to stay out of the monetary union.

Motivado por la experiencia reciente de Grecia y otros relativamente pequeños miembros de la Unión Monetaria Europea, este trabajo examina la decisión de tomar parte en una gran unión monetaria desde la perspectiva de las economías pequeñas y abiertas. Se demuestra que, en ausencia de consideraciones de política fiscal, el tomar parte en una gran unión monetaria es contraproducente para una economía pequeña. Sin embargo, una vez que el papel de la política fiscal se incorpora adecuadamente, tomar parte en la unión monetaria se vuelve deseable desde una perspectiva social. A raíz de estos resultados, se exploran diferentes esquemas de coordinación de la política fiscal y monetaria para mostrar cómo la cooperación puede beneficiar a los miembros de una unión monetaria. Encontramos que cuando las autoridades monetarias y fiscales cooperan e intentan explotar las externalidades para su propio beneficio, un resultado Pareto eficiente se puede lograr si la política fiscal en la unión monetaria es coordinada por una autoridad central y dicha autoridad actúa como líder à la Stackelberg frente al banco central. Nuestro análisis sugiere que este régimen es superior a (i) una unión monetaria en la que las autoridades fiscales llevan a cabo su política de forma independiente o (ii) de manera coordinada, (iii) un régimen en el que las dos autoridades internalizan los efectos de sus propias externalidades al permitir que el Banco Central actué como líder à la Stackelberg y (iv) un régimen en el que la pequeña economía abierta decide quedarse fuera de la unión monetaria.

We would like to thank Alberto Ortiz, Leonardo Torre, Carlo Panico, Gulcin Ozkan, Luis GonzálezMorales, Herb Newhouse and participants at the Money, Macro and Finance Research Group Annual Conference celebrated at the University of Warwick for their valuable comments. Any remaining errors are our own.

Providing that the SGP requires member states to aim for public budget balances which are close to equilibrium or in surplus in the medium term, the allocation of taxes and public expenditure would remain the only instruments in the control of EMU members to stabilize their economies against real shocks.

For other less recent papers employing symmetric models to assess monetary and fiscal policy coordination see, for instance, Cooper and Kempf (2004), Dixit and Lambertini (2003a; 2001), and Beetsma, Debrun, and Klaassen (2001), among others.

See Cabral (2010), Eichengreen and Ghironi (2002), Giavazzi and Giovanini (1998), and Ghironi and Giavazzi (1998) for other papers that employ asymmetric features in modeling monetary and fiscal policy coordination.

This is not unrealistic since, in principle, the Maastricht Treaty prevents the inflationary bias by stipulating that one-year before joining EMU, the accession country's inflation rate should not exceed by more than 1.5% the average rate of the three European Union (EU) countries where inflation is the lowest.

Interest rates in [8] also depend on shocks and on the stances of the monetary and fiscal authorities.

Consistent with SGP requirements, in our model fiscal deficits in both economies equal zero over time.

Considering the present size of EMU, this assumption is to some extent consistent with the current voting system of one country one vote and with the new proposed system of rotating groups in which larger countries have more power in the European Central Bank's monetary policy decisions and which will replace the former voting system as soon as the number of member states in EMU exceeds 15 (European Council, 2003).

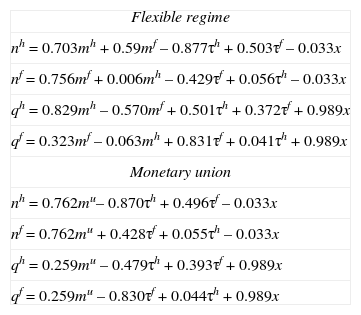

These reduced forms are also fully derived in Appendix A2.

Utilizing a three-country version of this model, Eichengreen and Ghironi (2002) study the determinants of policy trade-offs and incentives for central banks and governments in the U.S. and Europe. In their analysis, they consider the specific case of policy coordination between the U.S. and an EMU that consists of two economies of equal size.

This proportion is consistently employed in different macroeconomic models calibration (see for instance Cooley and Prescott, 1995; Kiley, 2004; Andrés, Doménech, and Fatás, 2004).

This parameter value is consistent with empirical evidence testing the Marshall-Lerner condition which suggests that elasticity of the demand with respect to imports and exports is usually below unity.

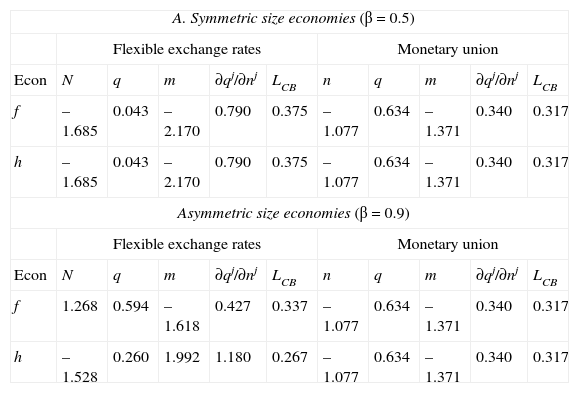

More details about the numerical reduced forms associated with this parameter value are presented in the following section.

As pointed out earlier, similar results were found by Martin (1995) studying the incentives for small open economies to join an already formed monetary union.

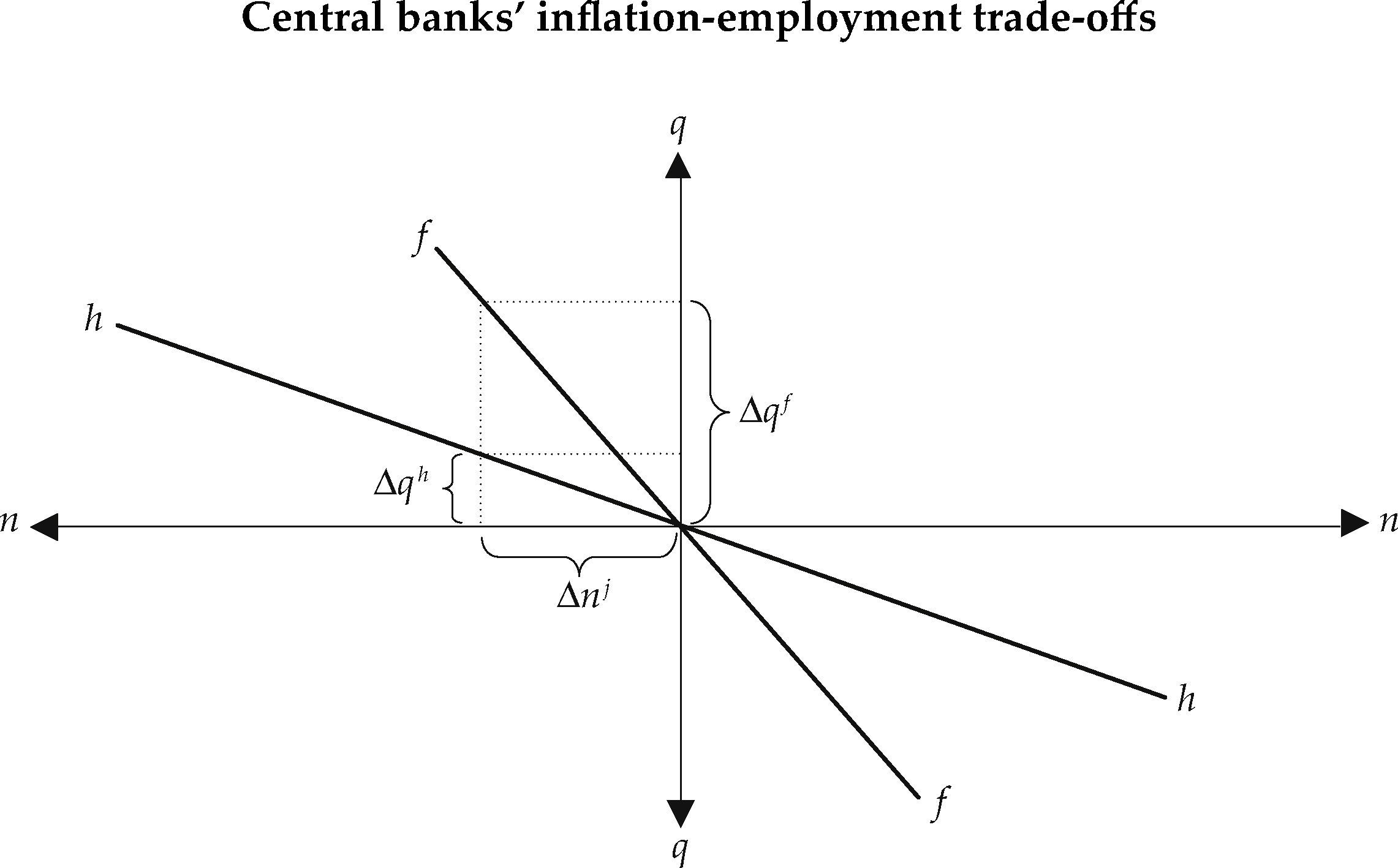

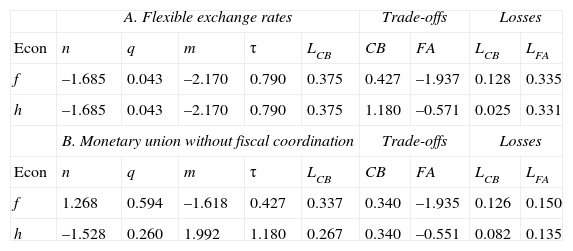

The trade-offs faced by monetary authorities are obviously the same as those presented before for the analysis of stabilization policies without fiscal authorities.

Extract from the Treaty of Amsterdam, Article 99 (European Council, 1997).

This is analogue to what we obtained in Table 2 when the central monetary authority decides on a single monetary policy instrument.

For some insight into the implementation of fiscal coordination schemes like those we have proposed, see, for instance, Fatás et al. (2003) and von Hagen (2004).

Without taking into account the new EU members, Artis and Buti (2001) estimate that an additional margin of 0.5 to 1 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) would be necessary to make room for unforeseen circumstances before balanced budgets are achieved in the EMU.

Photis Lysandrou is currently research professor at the Political Economy Research Centre in City University (CITYPERC), London. His research interests are in the areas of history of economic thought, Marx's monetary theory, corporate governance, globalisation and global finance. He has published on all these topics in Journals such as Cambridge Journal of Economics, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, Journal of Common Studies, and Economy and Society. Professor Lysandrou gave a series of lectures at School of Economics at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) during September, 2015.

Professor at the School of Economics at UNAM (Mexico)

EGADE Business School, Tecnológico de Monterrey and Center for Latin American Monetary Studies (Mexico), <aortizb@itesm.mx> . The views expressed in this comment are those of the author. </aortizb@itesm.mx>

Professor at the Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II (Italy) and visiting professor School of Economics at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM, Mexico)

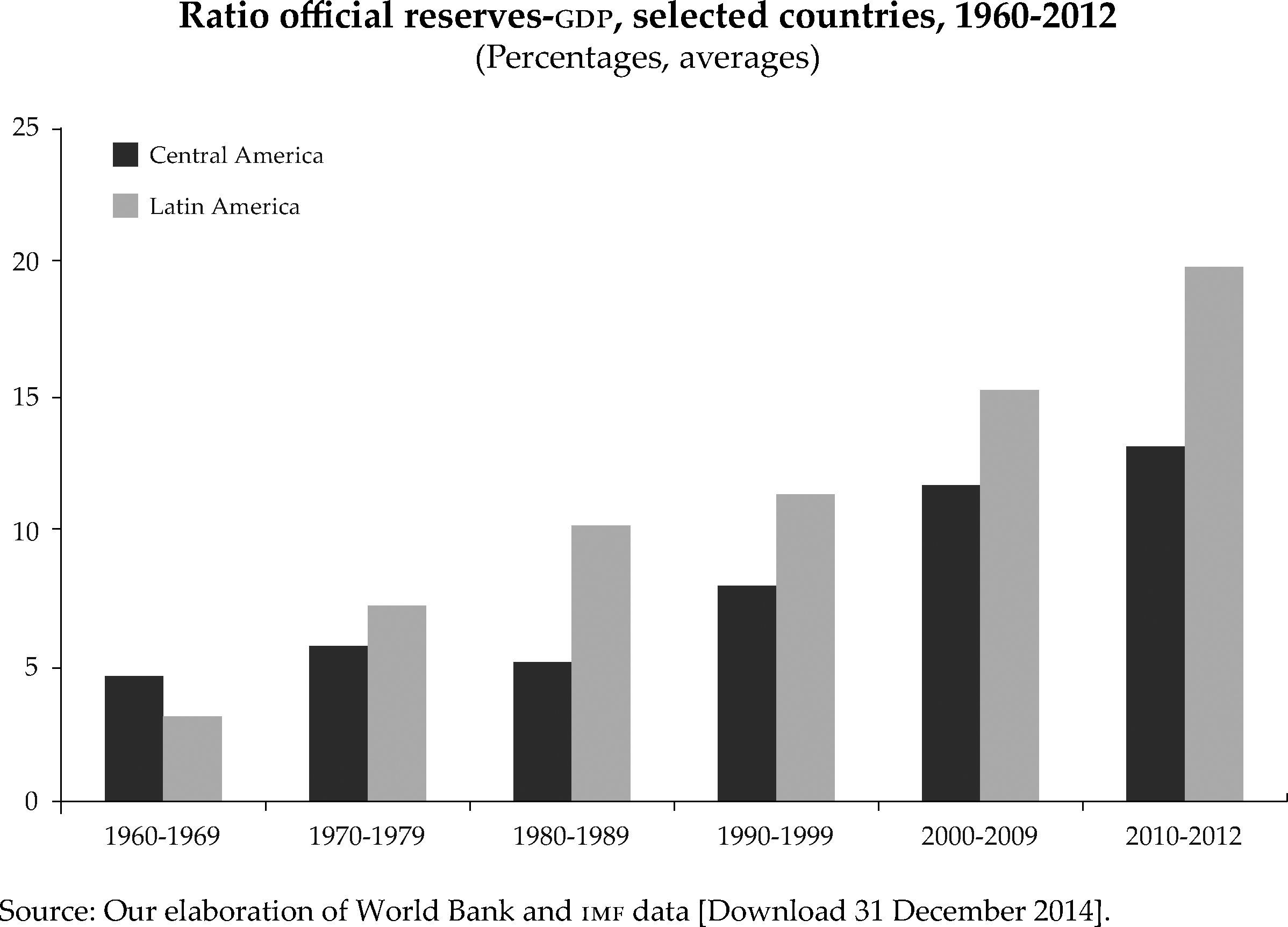

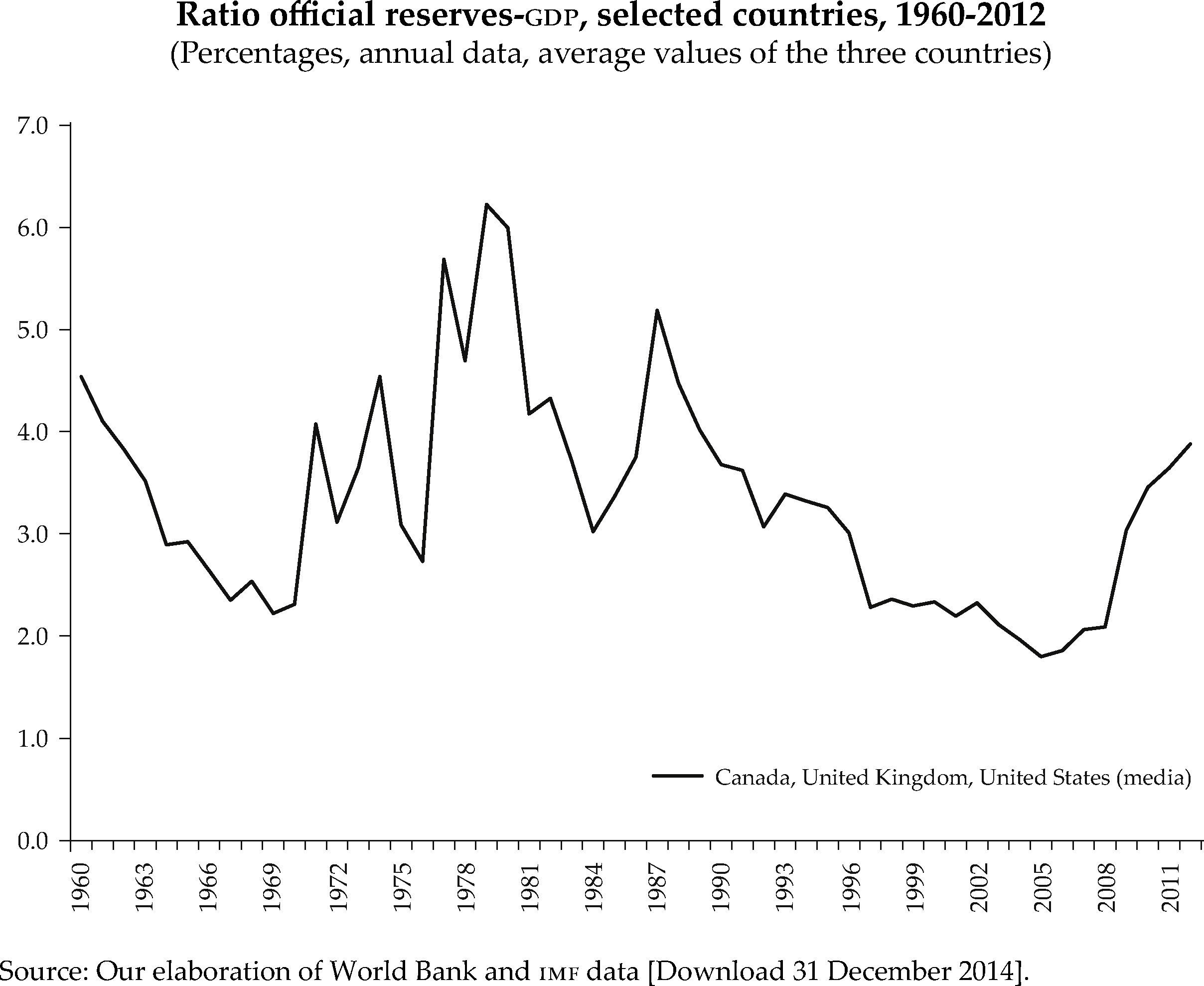

Canada moved from 5.1% of the 1960s and 1970s to 3.7% of the 1980s, to 3.3% of the 1990s and to 3.8% of the first decade of the new millennium. During the same five decades UK moved from 3.3 to 5.0, to 4.9, to 3.8 and to 2.3%. Finally, USA moved from 2.5% of the 1960s, to 2.7% of the 1970s, to 3.6% of the 1980s, to 2.2% of the 1990s and to 1.7% of the first decade of the new millennium.

In Mexico, in order to avoid reducing their profits, the central bank, without asking permission to the Treasury, issues government bonds that are purchased by the Mexican banks. The receipts of these issues are deposited in irredeemable accounts. The government sector owns these accounts, but cannot use them, in spite of the fact that it pays the corresponding interests (see Panico, 2014). For other problems generated by the accumulation of financial reserves, see Reinhart and Reinhart (1999) and Griffith-Jones, Montes, and Nasution (2001).

See Frenkel (2015) and Ros (2015). The latter points out that, in the case of the Mexican economy, what Calvo and Reinhart (2002) call fear to float is, as a matter of fact, a fear to devalue.

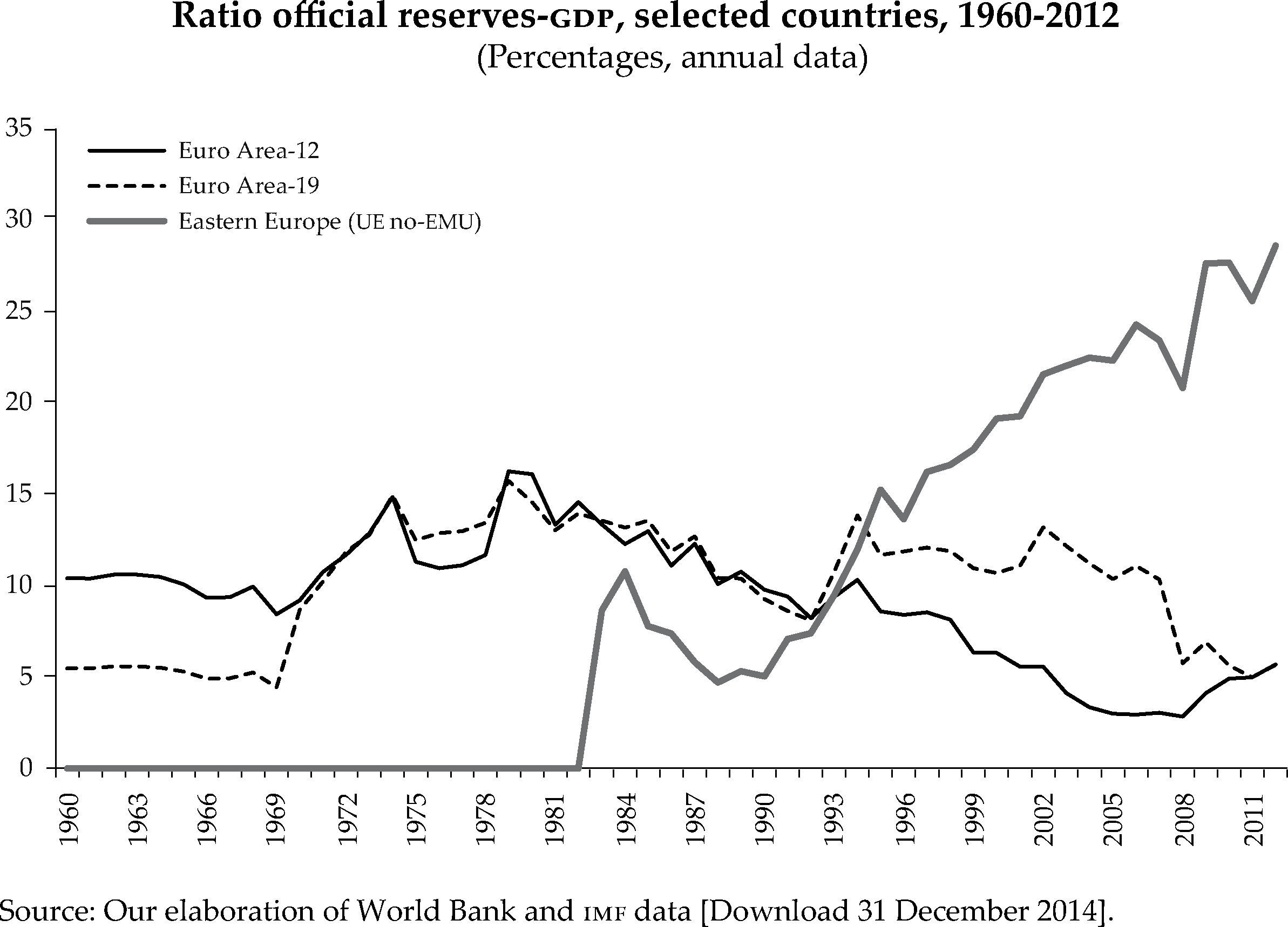

The twelve countries are: Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Holland, Ireland, Italy, Luxemburg, Portugal and Spain.

The seven countries that have entered EMU after 2002 are: Slovenia in 2007, Cyprus and Malta in 2008, Slovakia in 2009, Estonia in 2011, Latonia in 2014 and Latvia in 2015.

The countries of the European Union waiting to use the euro are: Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungry, Poland, Czech Republic and Rumania.

This tendency can be also noticed for the data of the individual countries. Germany for instance, has moved from 9.6% of the 1970s and 1980s to 5.2% of the 1990s and to 4.1% of the new millennium. Greece shows values around 5.5% until the 1980s, a sharp increase (10.3%) in the 1990s, before being admitted into the euro area and a pronounced fall (3.3%) during the participation in EMU. Spain moved from 4.4% in the 1960s to 9.5% in the 1990s to 3.1% in the new millennium.

According to Articles 258 and 271(d) of the Consolidated Version of the Treaty of the Union and of the Treaty on the functioning of the European Union (2008/C115/01) and to Articles 14.3 and 35.6 of the Statute of the European System of Central Banks and of the European Central Bank (Protocol n. 4 of the Consolidated Version, 2008/C115/01), in a case of conflict between a NCB and the ECB on the execution of the NCB's obligations, the ECB, after having exposed its reasons in a written document and after giving the NCB the opportunity to clarify its reasons, can ask the latter to conform its behaviour to the ECB's instruction within an established time. If the NCB still fails to follow the instructions, the ECB can ask the European Court of Justice to intervene and impose on the NCB the respect of its obligations.

Pisani-Ferry (2002), Fatás and Mihov (2003; 2010) and Fatás et al. (2003), von Hagen (2004) hold the same position.

Dirección General de Investigación Económica del Banco de México y Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León (México)