Chile is one of the oecd countries with higher levels of socioeconomic segregation in its educational system. This may be explained by the incidence of institutional factors (fees and school selection processes), sociocultural factors (families’ appraisals and behaviors towards school choice) and contextual factors, among which residential segregation would stand as the most relevant.

This article analyzes the relation between school location, students’ socioeconomic status and student's place of origin (mobility). The data used was gathered from 1613 surveys responded by primary students’ families. The results evidence that residential segregation only partially influences educational socioeconomic segregation, since the capacity of mobility is a key factor to “break” the association between both phenomena. Therefore, residential segregation would affect to a greater extent low socioeconomic status students who attend schools near their homes and travel distances shorter than children from higher socioeconomic status, who tend to cover longer distances between home and school. Nevertheless, the comparative analysis of the cases complicates drawing conclusions, because students of equal socioeconomic status travel very different distances. The characteristics of the territories where schools are located shed some light on the cause of these differences. From these results, we propose re-discussing the use of the residential segregation concept for explaining phenomena like school segregation, due to the complex interrelations between both territorial fragmentation and urban mobility.

Chile es uno de los países ocde que exhibe mayor grado de segregación socioeconómica en su sistema escolar. Esto se explicaría por la incidencia de tres factores: institucionales (como los cobros y procesos de selección de estudiantes por parte de las escuelas), socioculturales (valoraciones y comportamientos de las familias frente a la elección de escuela) y de contexto, entre los que la segregación residencial aparece como el más relevante.

Este trabajo analiza la relación entre localización de las escuelas, composición socioeconómica del alumnado y procedencia (movilidad) del mismo. La información utilizada proviene de 1 631 encuestas a familias de alumnos de enseñanza primaria. Los resultados evidencian que la segregación residencial influye sólo parcialmente sobre la segregación socioeconómica escolar porque la capacidad de movilización es un factor determinante para “romper” la asociación entre ambos fenómenos. La segregación residencial afectaría en mayor medida a estudiantes de nivel socioeconómico bajo que asisten a escuelas en las inmediaciones de sus hogares, recorriendo distancias menores que niños de niveles socioeconómicos superiores quienes tienden a movilizarse más entre casa y escuela. Sin embargo, el análisis comparativo de los casos complejiza esa conclusión, porque estudiantes del mismo nivel socioeconómico pueden recorrer diferentes distancias. Las características de los territorios donde se localizan las escuelas parecen tener relación con tales diferencias. A partir de los resultados del estudio se plantea rediscutir el uso del concepto de segregación residencial para explicar fenómenos como la segregación escolar dada la complejidad de las interrelaciones entre procesos de fragmentación territorial y movilidad cotidiana.

In Chile, there is a consensus regarding the high levels of socioeconomic segregation that characterize the school system1 (Ministry of Education, 2012), which has been endorsed by international reports (OCDE, 2013). In turn, there is also agreement on the different nature of the elements that explain school segregation. Bellei (2013) organizes them in three dimensions: institutional factors from the educational system (fees and school selection processes), sociocultural (families’ preferences) and contextual factors, among which residential segregation would stand as the most relevant.

International studies have shown how the link between both school and residential segregation would be especially evident in school systems subjected to zonification policies that limit school choice to the institutions closest to the student's home (Taylor & Gorard, 2001; Ong & Rickles, 2004; Alegre et al., 2008). Along with the spread of the neoliberal economic model, school zonification has been questioned and replaced by a market orientation (Collins & Coleman, 2008), emphasizing freedom of school choice as a key mechanism to stimulate competition between schools, and to promote the improvement of the quality of education. Therefore, in theory, the link between a school and the population that inhabits its location is weakened in the free choice scenario. As aforementioned, in the Chilean case, despite the existence of zonification policies and the relevance of free choice, it is assumed that “urban segregation has a direct incidence on the school system, since more segregated neighborhoods and cities tend to reproduce social differences in the school system” (Valenzuela et al., 2013:12). Moreover, some authors proposed that school segregation might be the mere reflection of residential segregation2.

Therefore, from the geography of education perspective (Taylor, 2009; Collins & Coleman, 2008), it is considered that educational processes have a particular spatial projection, which influences the territory where these processes occur and, in turn, is influenced by them. Therefore, to reach a deep understanding of educational systems, it is necessary to study them from a territorial approach, in which the territory is conceived as a constant process of social construction (Raffestin & Barampama, 1998; Santos, 2000; among others).

This study is oriented towards that path, as it studies whether and how spatial segregation influences school segregation in the Chilean school system and, with respect to these phenomena, to what extent students’ capacity/ possibility of commuting influences them. The work is divided into four sections. The first section reviews antecedents concerning residential segregation, city morphology and daily mobility in the Chilean case, referring to studies that address these concepts from the education field. Subsequently, the methodology and results of this research are presented in sections 2 and 3, respectively. Finally, conclusions that put in evidence coincidences with previous studies as well as novel contributions to the field are provided.

Residential segregation in Santiago de Chile? Scale of analysis, urban mobility and city morphology: elements for a still open discussionSince school segregation would be related to residential segregation, it is necessary to clarify what is understood by residential segregation in the case of Chile.

The concept of residential segregation arouses from studies on the racial segregation of Afro-American and new immigrant groups in the United States (Ruiz-Tagle, 2013). Subsequently, this concept was reinterpreted in order to describe certain processes of Latin-American metropolises. In this context, the term has been related to the urban transformation experienced during the last 30 years (Janochska, 2002), placing especial emphasis on the spatial distances that separate the different socioeconomic groups that inhabit cities (Sabatini et al., 2001).

As for the Chilean case, at the end of the last century, De Mattos drew an analysis of the transformation and growth processes experienced in the Metropolitan Area of Santiago (MAS) since the mid-seventies, pointing out that “what already existed continues to exist” (De Mattos, 1999). The author emphasized that the new elements that characterized urban expansion since the return of democracy should be considered a “reproduction” (updated by economic globalization processes) of the same territorial logics instituted after the political and economic reforms of the civil-military dictatorship. Likewise, De Mattos highlighted that this renovation of urban morphology was described by three factors: formation of a regionmetropolis, suburbanized, polycentric and with a vast peri-urban/semi-rural territory; cities with less poverty and indigence but extremely fragmented; and consolidation of a set of “new urban artifacts” (big shopping malls, gated condominiums, decentralized business centers, etc.) as articulators of the metropolitan space.

Studies from the past 25 years on Santiago's urban territory renovation have substantially delved into the idea posited by De Mattos, emphasizing the social, political and cultural implications of this model of territorial growth. The influence of land prices on the formation of some communes is a common element in these studies. Some of them underline the role of real estate agencies, favored by the neoliberal ideology governing the State, in the transformation of the urban morphology and social fabric, which has yielded gentrification phenomena (López, 2013), and, in turn, a counter-hegemonic response from social movements (Casgrain & Janoschka, 2013). Other studies have focused on how the expansion of the metropolitan area has absorbed peri-urban and rural zones, particularly thanks to the spread of a gated communities residential model, directed to groups from different socioeconomic status, which are also differentiated by their connectivity to the center (or centers) of the city (Salazar & Cox, 2014).

This leads some authors to propose that Santiago evolves towards a polycentric structure, with places concentrating commercial activity being more prominent (Truffello & Hidalgo, 2015). This differentiation or fragmentation of space in commercial terms would be closely related to residential segregation processes (Ducci, 2000).

Along with the factors abovementioned, the territorial expansion of Santiago has implied an increasing complexity of urban mobility, heightened since 2007 due to the change of the “public” bus transportation system3. Several studies (Delunay et al. 2013; Jouffe & Lazo, 2010), using different methodologies, have revealed that the place of residence, socioeconomic status, cultural and material capital influence mobility strategies, and that these elements may increase social exclusion and segregation.

Many authors have interpreted all these transformations in Santiago as an increasingly profound exacerbation of residential segregation. The study of such a phenomenon has centered on its small and large-scale effects. Large-scale segregation has been associated with the construction of social housing promoted by governmental programs in the outskirts of the city. Meanwhile, small-scale segregation has had different interpretations (Stillerman, 2016) and a number of studies have focused on evidencing the level of social homogeneity in the spatial proximity within cities (Cáceres & Sabatini, 2004, Hidalgo, 2004; Ortiz & Escolano, 2013; among others).

On the other hand, the socioeconomic residential segregation and its applicability to the case of Santiago de Chile has been questioned due to the difficulties found in its definition and measurement (Agostini, 2010). In this sense, Ruiz Tagle & López (2014) propose that studies tend to show flaws in the form in which socioeconomic status is perceived and measured. Furthermore, supposing that a good indicator is finally defined, the problem that subsequently arouses is at what scale it should be applied. Is the commune, the metropolitan area or the neighborhood the most appropriate dimension? If the scale were to be solely considered in terms of size (Gutiérrez Puebla, 2001), another problem would arouse: do administrative limits reflect effectively coherent and heterogeneous territories? (Bissonnette et al., 2013; Ross et al., 2004; Iturra, 2014; Ruíz-Tagle and López, 2014). The problem of the scale, thus, is associated with the morphological peculiarities of the city and its process of social construction.

In line with this view of the city, several studies have placed emphasis on the need of considering daily mobility one of the factors that contribute to the social construction of a territory and, thus, to residential segregation.

Jirón et al, based on a review of new approaches on mobility4 and on systematic fieldwork, underline the static view of the space and social exclusion usually assumed in studies on residential segregation, which neither takes into account the different “people's fields of activity (labor, educational, recreational fields) nor the way people daily commute to carry out such activities” (Jirón et al., 2010: 37). These authors regard daily mobility5 as a factor that overcomes static conceptions of the urban space, underlining the fact that mobile experiences are multiple, fluid, scaled, processual, and that generate important inequalities, especially those originated from the power of “rich-no time” versus “poor-plenty of time” users (Jirón et al., 2010: 27).

These divisions show that accessibility is distributed unequally among individuals and in space; not all people have the possibility to access, due to economic or cultural reasons, to work, leisure and consumption places, activities and persons, resources and opportunities; nor all places have the same infrastructural conditions or are benefited by transportation policies. Therefore, mobility is a crucial element to be considered when studying fragmentation and socio-spatial exclusion processes such as school segregation.

The trends outlined for Santiago are reflected in the distribution of schools across the territory as well as the distance that students travel from home to school. Diverse studies document the variation of the educational offer across different areas of the city, existing an association between the resident population socioeconomic status, and the administration modality of the institutions present there (Astaburuaga, 2013; Flores & Carrasco, 2013). Likewise, a recent study reports the existence of a considerable amount of daily trips made by students, at all educational levels and in all types of school, from the commune where students reside to that where they study (Rodríguez et al., 2016). In addition, even when a shorter distance between home and school would be positively valued by families from different socioeconomic status, it has been established that parents with higher income and/or education level travel longer distances to take their children to school; while parents from lower socioeconomic status tend to choose schools close to their homes and travel shorter distances (Gallego & Hernando, 2009; Chumacero et al., 2011; Flores & Carrasco, 2013; Alves et al., 2015). In this line, other study by Donoso & Arias (2013) points out that students who attend voucher private schools show greater daily mobility than those from municipal schools.

To summarize, research shows that Santiago has expanded and become more complex and fragmented. In this urban morphology transformation, mobility has played an important role in socioterritorial terms, therefore both morphological and mobility characteristics are factors to be taken into account for the study of school segregation.

MethodologyThis research analyzes socioeconomic segregation among institutions that offer primary education, because parents of small children would tend to send their children to schools near their homes (Gallego & Hernando, 2009; Chumacero et al., 2011), and segregation would be more intense at this level (Valenzuela et al., 2014).

Considering the reflections made on the different processes that coalesce into the construction of urban morphology, specifically in the fragmentation presented in the city at different scales, a methodology focused on the small scale (micro neighborhoods) and, at the same time, projected at a commune and metropolitan scale was selected. The small-scale approach allows for considering the peculiarities of the fragments of the urban space where certain schools are located, while the commune and metropolitan scale permits to analyze broader processes, such as those determined by daily mobility.

The unit of analysis has been defined not in terms of a predefined administrative division (census, commune or region) that often may be inappropriate to explain territorial processes (Bissonnette, 2012), but it terms of key factors that should determine school segregation. If parents choose a school because of its closeness and if schools reflect the residential segregation of a place, the definition of the territorial unit should have the presence of one or more schools as a priority element. The hypothesis is that if in a specific territory exists only one school, the vast majority of children living nearby will attend this school; but if at a short distance there is another educational institution, school-age population will be divided between those two institutions.

Therefore, the unit, denominated Fenced Geographical Unit (fgu), is a small territory characterized by the existence of two or more schools located close to each other6. The analysis of small territories allows for studying in detail the segregating dynamics at stake. It consists in a case study that prioritizes a deep understanding of complex units to analyze a phenomenon that involves different dimensions (Della Porta, 2013).

This study uses cluster sampling. Each fgu corresponds to one cluster that was intentionally selected according to the technical definition provided. Data was collected from both semi-structured interviews (with families and school officials) and surveys. The census-based survey at fgu level was directed to parents of kindergarten to fourth grade primary students who attended the establishments that formed the units. The survey consisted in a self-administered questionnaire filled in without the presence of an interviewer, which incorporated open-ended and closed-ended questions about the socioeconomic status of the students’ home and school. This last datum allowed for calculating the on route distance that students travel from home to school.

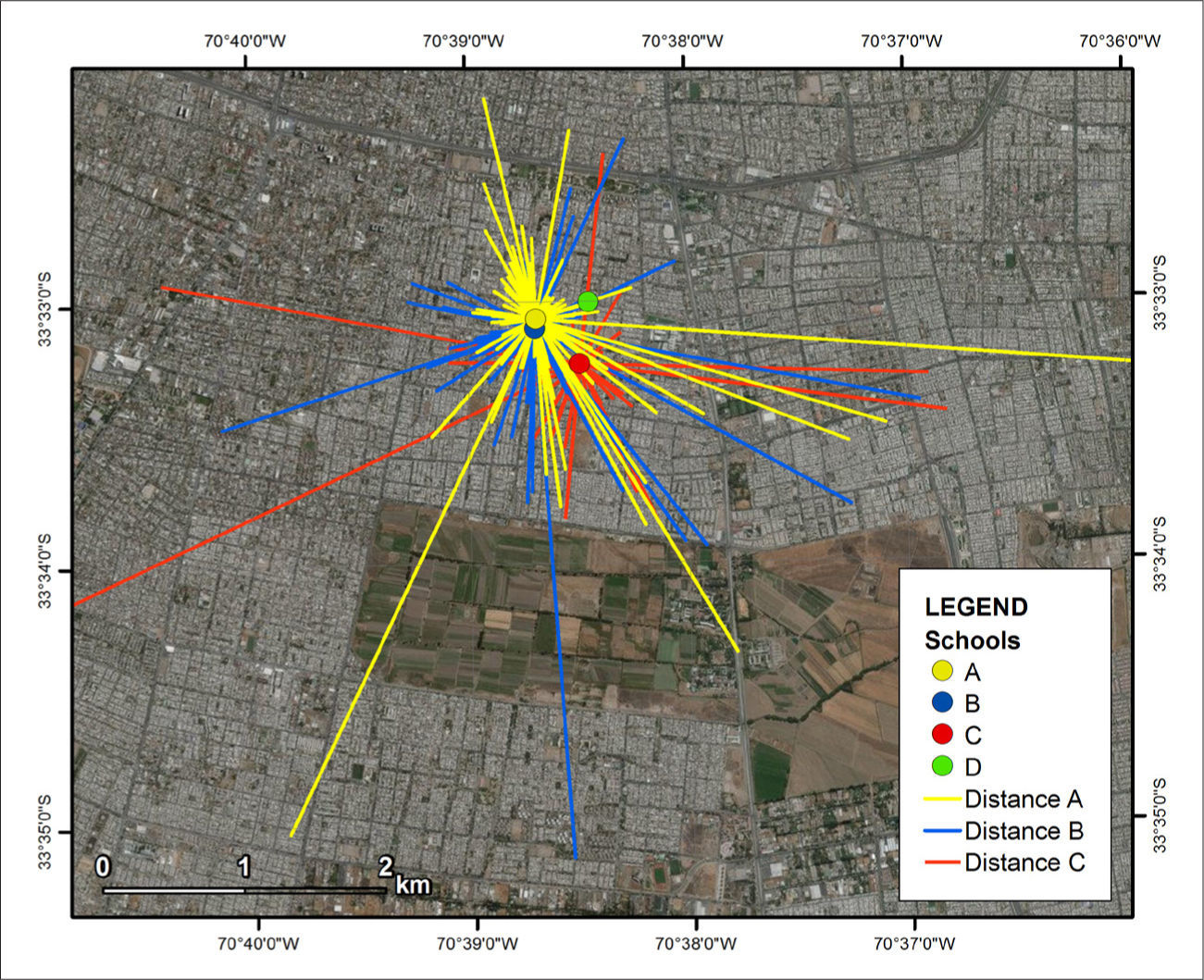

The type of questionnaire employed has a regular and varied rate of response; however, the sample size at the cluster level was sufficient to conduct a reliable statistical analysis. In fact, the average rate of response by school was 45.7%, with a standard deviation of 13.5%, and minimum and maximum values of 17.7% and 75.9%, correspondingly. These rates do not substantially differ from the theoretically established criteria for a self-administered survey (De la Poza et al., 2003). The data presented correspond to information from 1613 surveys with localized domiciles7 collected between 2014 and 2015 in 10 fgu composed of 21 educational institutions: 12 municipal schools, 7 voucher private schools and 2 non-subsidized private schools. These FGUs are located in 8 communes of Santiago, as shown in Figure 1.

In 81% of the cases, the survey was responded by the student's mother, in 11% by the father and 5% by other relative. Twenty-nine percent of mothers declared having less than 12 years of schooling, while 32% reported having 12 years and 33% more than 12 years. With respect to household incomes, 62.7% of homes lives with less than clp 500.000 per month, 11.7% reported receiving between clp 500.000 and clp 800.000, whereas 23.5% of homes monthly receive more than clp 800.000. The socioeconomic composition of the sample is similar to that of simce8 2013 in the Metropolitan Region (Annex, Table 1).

Results presentationBelow is presented the descriptive analysis of the variable “on route distance between home and school”. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov's goodness-of-fit test reveals that this variable does not behave like a normal distribution. Therefore, parametric analyses were discarded and non-parametric statistical techniques, such as the Krhuskall Wallis test were chosen instead to evaluate statistically significant differences between the medians of two or more independent samples.

A first element to take into account is that primary students travel about 2.5 km to school (Annex 2, Table 2), distance almost three times superior to the walkable distance defined by the literature (Munizaga & Palma, 2012). Furthermore, 37% of students live at one or less kilometers from school while 63% travel longer distances, which is almost 20 points above the reported by Alves et al. (2015). In addition, an important proportion of students with mothers whose level of education is less than 12 years of schooling (53%) or from households with incomes below clp 200.000 (47%) attends schools located more than one kilometer away from their homes (Annex, Table 3).

Meanwhile, the distance that students travel is significantly different among units, e.g., in fgu 2 half of students from the two educational institutions of the unit travel more than 3.4 km to school every day, whereas half of the students from the three schools of fgu 5 travel less than 600 meters. This reveals that, to arrive at school, children travel distances that may be very heterogeneous (Annex, Table 4).

In addition, it is observed that, in some cases (fgu 2, 4, 8, 9 and 10), there is a statistically significant difference in distance among the institutions composing a FGU, which shows that schools very close to each other may receive students that travel different distances. The most representative case is FGU 8, in which differences of up to 3km between schools are observed in median (Annex, Table 5).

Likewise, it is confirmed that students tend not to attend the educational institution that is closest to their home, with only 11.7% doing so (Annex, Table 6). This number is below the 17.6% documented by Chumacero et. al. (2011). Again, significant differences may be seen across FGUs, with greater proportions of students attending the school closest to their home in some units than in others. In fgu 9, none of the students attends the closest school, while in fgu 4 this percentage corresponds to 23%, and rises to 34% in fgu 8. (Annex, Table 6).

In the heterogeneous scenario described, it is possible to observe that students who attend municipal schools tend to travel shorter distances than those attending voucher private schools and, in turn, the latter travel less than students from non-subsidized private schools do. Half the students attending non-subsidized private schools travel more than 2.6 kilometers in comparison with half of students from voucher private and municipal schools, who travel less than 1.4 and 1.2 km, respectively (Annex, Table 7). Likewise, attendance to the school that is closest to home occurs in 15.7% of children from the municipal sector and around 7% of students from the private sector (subsidized or not) (Annex, Table 8). On the other hand, our analyses show a directly proportional relation between the families’ income level and the distance traveled between home and school. While half of the students who live in homes with incomes below clp 300.000 travel one kilometer or so to school, half of students from homes with incomes above clp 800.000 travel 2.5 km (Annex, Table 9).

To summarize, our results confirm the association between socioeconomic status and distance traveled between home and school documented by other studies (Donoso & Arias, 2013; Gallego & Hernando, 2009; Chumacero et al., 2011; Elacqua & Santos, 2013; Flores & Carrasco, 2013). However, along with this result, it should be highlighted the great proportion of students from lower socioeconomic status who travel more than 1 km to school, existing —besides— noticeable differences among fgus and, in some cases, between the schools that form these units. At this point, it becomes necessary to analyze the specific characteristics of these territories in order to generate a hypothesis that allows for explaining the extremely heterogeneous scenario described up to this point. Therefore, three FGUs with different territorial characteristics but descriptive of the morphology of Santiago will be analyzed.

First case: FGU 5It is compound of four educational institutions: three municipal schools (A, C and D) and one voucher private school (B). It was possible to gather information of three of them (A, B and C). The socioeconomic status of students from schools B and C was classified as low by simce 2013, while that of students from school A was categorized as low middle.

This fgu is located in a commune south of Santiago, in a neighborhood known as one of the most prominent social housing initiatives at a regional level. Its origin dates from illegal occupancies of land that took place in the late 60s. Over the years, these improvised houses were improved by their own owners. This fgu is a predominantly residential area, which accommodates families from low-middle and low socioeconomic status, with scarce territorial attractions and poor connectivity. The unit is made up mainly of houses, small shops and basic services units (educational institutions, primary and mental health centers, police stations) and is characterized by the existence of small rectangular blocks. The nearest subway station is located 1.15 km from this uga center, at the same distance from the most important close avenue. The most available mean of transportation is the bus, although there are also passenger taxis, whose fare is higher than bus fares.

The schools of this fgu receive students that travel very short distances from home: half of them travel less than 600 m. The limited connectivity of the place might influence the decisions of families, who would discard the option of sending their children to more remote schools. This hypothesis is also sustained by studies evidencing that lower class workers travel shorter distances to work than middle and upper class workers (Delunay et al., 2013), which might be due to the fact that they work in informal sectors whose activities take place in the city outskirts (Suárez et al., 2015).

Figure 2 represents fgu5, indicating the schools located in it and the points of origin of the trips to them.

Second case: FGU7fgu7 is located in a central commune of Santiago city and is compound of two municipal schools, A and B. Students from school A were classified by simce 2013 as from middle socioeconomic status, while its school B counterpart were classified as low-middle.

There is a subway station 520 m away from these schools, in the intersection between an important avenue and a highway. Thus, there is a great provision of public transportation and private transportation is enhanced. The premises of two important public institutions are located 300 m away, as well as a private higher education institution. Nearby —about 250 m—, is one of the biggest urban parks within the commune and Santiago. Therefore, UGA 7 may be considered a resourceful territory with good connectivity.

Students travelling very heterogeneous distances attend both schools: 90% of them travel from 250 m to 12 km, half of them travel around 1.6 km, and the distance traveled by students in both schools is 3km on average. Almost all students (98%) have another educational institution closer to their homes. Thus, in this case, it may be supposed that the presence of certain territorial ‘objects’ enables the flow of students from other areas of the city to the schools in this FGU. Figure 3 represents FGU7 as well as the points of origin of the trips to them.

Third case: FGU8fgu8 arouses our interest because the two formerly described contexts take place in the same territory. This unit is compound of three educational institutions, one of each type. It was possible to collect data from two of them, namely the municipal school (A) and the non-subsidized private school (C). According to simce 2013, students from the former are from low socioeconomic status, while students from the later are from high socioeconomic status. Based on our data, 84% of families whose children attend the municipal school have an income below clp 400.000, while 70% of families from the non-subsidized private school have a monthly income above a clp 2.000.000.

This fgu is located in a commune of the southeast area of Santiago city. It was a predominantly rural area until the 80s, when slowly started to undergo a profound transformation. On the one hand, great part of the settlers evicted by the military government ended up in this commune. On the other hand, land divided into lots was sold to construction companies that built gated condominiums and neighborhoods directed to middle and upper class families. Therefore, in this commune, families from very different socioeconomic status currently coexist (Pérez & Roca, 2009).

The arrival of these ‘new neighbors’ has brought along the construction of large buildings, together with a series of small shops and services. Likewise, new private educational institutions have settled in this place, including the non-subsidized private school of this fgu.

The neighborhood where this fgu is located is arranged along an avenue, one of the communes’ main (public and private) vehicular traffic arteries. The nearest subway station is located approximately 1.2 km away from the fgu center, which also contains a big shopping mall. On one side of the avenue are social and self-constructed houses as well as small shops; while on the other side are large areas of unbuilt land. Around 400m from the fgu center are placed the gated condominiums where families with highest purchasing power reside.

Students who attend the non-subsidized private school travel on average much longer distances (4 km) than their municipal school peers (1 km) do. Likewise, half of the students attending the first school travel more than 3.5 km, while half of the students from the other school travel only 0.4 km. In the municipal school, 75% of students attend the educational institution closest to their home, whereas the reverse is true for almost all students from the non-subsidized private school.

This case reveals how the reduction in physical distance does not imply a reduction in social distance (Ruíz-Tagle & López, 2014; Ruíz-Tagle, 2016), in spite of being really close to each other (300 m), the two schools do not target the same population (Figure 4).

Conclusions and projections of this studyThis study presents some developments with respect to the studies on school segregation conducted thus far that should be noted.

Methodological contributions to the study of school segregation: scale of analysisThe scale used was not predetermined according to an administrative division (census, commune, region district), but defined based on the hypothesis about the factors that determined school segregation. This novel methodology is decisive for interpreting the results. Once established that students travel different distances depending on their socioeconomic status, the analysis focused on identifying the morphological characteristics and the “pull” factors of the places where schools were located to show the heterogeneous picture of mobility in the different cases studied.

Influence of residential segregation on school segregationThe results of this study indicate that students tend not to attend the institution closest to their home, travelling average distances of around three kilometers to school. Although this is true for students from all socioeconomic status, there is a positive association between the distance traveled and this variable. An analysis of these new data leads us to the conclusion that residential segregation would not be equally important to explain school segregation, and that it would be more important in the case of disadvantaged sectors. From this perspective, the results are coincident with other studies that point out the secondary effect of residential segregation on school segregation with respect to other institutional and sociocultural factors that are considered more relevant (Elacqua & Santos, 2013; Valenzuela et al., 2014). Nevertheless, the comparative analysis of the cases complicates drawing conclusions, because students of equal socioeconomic status travel very different distances. As shown, the characteristics of the territories where schools are located shed some light on the cause of these differences. This leads us to propose that, the factors that probably explain school segregation behave differently depending on the context, i.e. factors such as urban morphology, mobility strategies, parents’ preferences, socioeconomic status and type of school interact in differentiated forms.

Influence of urban morphology and mobility on school segregationThe concept of socioeconomic residential segregation does not appear appropriate to the analysis of school segregation, due to the current debate about it and its limitations. Instead, it is the form of the city, together with its peculiar urban morphology, the “objects” and “actions”, which daily render the city the object of study. Educational processes are also part of this construction. In this sense, the fact that only a small minority of students attends the school closest to its home indicates that mobility strategies would have a significant weight in school choice. Therefore, on the one hand, the capacity/availability to commute “breaks” the conditioning factor of residence and, on the other hand, exacerbates the social consequences of spatial fragmentation, creating inequality in the access to the services of a city. This situation is evident in FGUs 5 and 7, where there seem to be “comparative advantages” of the place in terms of accessibility, workplaces, among others.

Contributions to the debate on residential segregationCertain aspects of the Chilean educational policy not only imply social competitiveness and selection processes within the educational space, but also, at certain scales and places, potentiate the existing socio-territorial fragmentation dynamics, which is inherent to the current morphology of the metropolis. This is the case of FGU8, which is a small territory fragmented in socioeconomic terms and characterized by the existence of educational institutions very close to each other, but targeting different populations. In line with the documented by Ruiz Tagle (2016), children that reside at short distances between each other do not share the same spaces. Moreover, they attend different types of school, which are differentiated by fees.

To summarize, these results compel us to propose an integrated approach to the relation between spatial and educational processes, considering the four fundamental concepts of the geographical lexicon, namely place, territory, scale and network. As suggested by Jessop et al. (2008), each of these elements represents a part of the socio-spatial organization and considering only some of them may lead us to wrongly believe that the part is the whole. As for the last concept, network, the projections of this study focus on the analysis of the mobility strategies of families. Since these practices are hybrid, in other words, the majority of trips has more than one objective (Jirón et al., 2010), we hypothesize that the routes of students that travel longer distances to school are associated with other family purposes, such as going to work. This is one of the pending tasks that will be addressed in further stages of the study.

We would like to thank the Chilean National Commission for Scientific and Technological Research (conicyt) for funding this study through the Project fondecyt 11130149 “Analysis of socioeconomic school segregation in primary school”.

The study used the database of the Quality of Education Agency. The authors would also like to give thanks to the institution for granting access to this information. All the results of this research are exclusive responsibility of the authors and do not commit the referred institution.

Finally, we would like to extend our thanks to the reviewers who commented the first version of this work as well as to Manuel Vallejos Caroca, who elaborated the cartography.

Educational level of mothers and household income, study sample and simce 2013 database (4th grade, Metropolitan Region).

| Mothers’ educational level | Sample | simce 2013, mr | Income quintile | Sample | simce 2013, mr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 12 years | 29.1 | 28.5 | I Less than CLP 200,000 | 16.6 | 19.9 |

| 12 years | 32.2 | 34.6 | II Between CLP 200,001 and 300.000 | 23.4 | 21.3 |

| More than 12 years | 33.0 | 34.8 | III Between CLP 300,001 and 500.000 | 22.7 | 22.3 |

| V More than CLP 800,001 23.5 | IV Between CLP 500,001 and 800.000 | 11.7 | 12.3 | ||

| 22.6 | |||||

Proportion of students that travel more than 1 km by educational level of mothers and income quintile.

| Mothers’ educational level | Up to 1 km. | More than 1 km. | Income quintile | Up to 1 km. | More than 1 km. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 12 years | 47.0% | 53.0% | I Less than CLP 200 000 | 53.3% | 46.7% |

| 12 years | 39.4% | 60.6% | II Between CLP 200 001 and 300 000 | 41.6% | 58.4% |

| More than 12 years | 23.5% | 76.5% | III Between CLP 300 001 and 500 000 | 38.0% | 62.0% |

| Total | 36,8% | 63.2% | IV Between CLP 500 001 and 800 000 | 26.6% | 73.4% |

| V More than CLP 800 001 | 21.4% | 78.6% |

Descriptive statistics variable distance home-school by fgu.

| FGU | N | Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | Percentiles | Kruskal — Wallis Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 50 | 75 | Chi2 | df | Asympt.Sig. | ||||||

| 1 | 184 | 2544.1 | 2712.6 | 141.0 | 16624.0 | 699.0 | 1507.0 | 3709.3 | 411.1 | 9 | .000 |

| 2 | 192 | 4380.3 | 4007.0 | 81.0 | 23508.0 | 1863.8 | 3470.5 | 4795.0 | |||

| 3 | 146 | 1862.6 | 2248.1 | 322.0 | 24093.0 | 1031.0 | 1494.0 | 2184.5 | |||

| 4 | 197 | 923.1 | 1600.7 | 52.0 | 15208.0 | 375.0 | 583.0 | 876.0 | |||

| 5 | 135 | 865.3 | 930.2 | 35.0 | 5991.0 | 341.0 | 575.0 | 1050.0 | |||

| 6 | 104 | 3086.0 | 4190.5 | 141.0 | 21950.0 | 924.5 | 1536.0 | 3183.5 | |||

| 7 | 106 | 2972.0 | 3181.4 | 210.0 | 18500.0 | 1110.8 | 1670.0 | 3872.5 | |||

| 8 | 124 | 2938.6 | 2888.7 | 72.0 | 11544.0 | 455.3 | 1989.5 | 4299.5 | |||

| 9 | 198 | 3142.7 | 2753.2 | 220.0 | 16126.0 | 1285.0 | 2270.0 | 3812.3 | |||

| 10 | 262 | 2455.0 | 3658.3 | 17.0 | 29083.0 | 776.3 | 1919.0 | 2993.5 | |||

Descriptive and Contrast Statistics variable distance home-school by FGU and school.

| FGU | School | S.E. level simce 2013 | N | Mean | Median | Min. | Max. | Kruskal — Wallis Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chi2 | df | Asympt.Sig. | ||||||||

| 1 | A | Middle | 17 | 1793.3 | 1289.0 | 141.0 | 5835.0 | .348 | 1 | .555 |

| B | Middle | 167 | 2620.5 | 1549.0 | 242.0 | 16624.0 | ||||

| 2 | A | Middle low | 85 | 3648.1 | 2379.0 | 81.0 | 14959.0 | 6.633 | 1 | .010 |

| B | Middle high | 107 | 4962.0 | 3635.0 | 559.0 | 23508.0 | ||||

| 3 | A | Low | 63 | 1577.5 | 1346.0 | 322.0 | 4400.0 | .896 | 1 | .344 |

| B | Middle low | 83 | 2079.0 | 1616.0 | 409.0 | 24093.0 | ||||

| 4 | A | Low | 84 | 741.6 | 503.5 | 114.0 | 9233.0 | 7.579 | 1 | .006 |

| B | Middle low | 113 | 1058.1 | 665.0 | 52.0 | 15208.0 | ||||

| 5 | A | Middle low | 35 | 669.0 | 637.0 | 35.0 | 1808.0 | 3.759 | 2 | .153 |

| B | Low | 52 | 1027.2 | 689.0 | 43.0 | 5991.0 | ||||

| D | Low | 48 | 833.1 | 511.0 | 58.0 | 5289.0 | ||||

| 6 | A | Middle high | 42 | 3546.4 | 1933.0 | 141.0 | 21698.0 | .317 | 1 | .573 |

| B | High | 62 | 2774.1 | 1531.0 | 186.0 | 21950.0 | ||||

| 7 | A | Middle | 59 | 2901.4 | 1394.0 | 210.0 | 15670.0 | 2.620 | 1 | .106 |

| B | Middle low | 47 | 3060.6 | 2368.0 | 308.0 | 18500.0 | ||||

| 8 | A | Low | 51 | 1070.3 | 404.0 | 72.0 | 9709.0 | 57.905 | 1 | .000 |

| C | High | 73 | 4243.8 | 3584.0 | 308.0 | 11544.0 | ||||

| 9 | B | Middle high | 119 | 3609.2 | 2792.0 | 255.0 | 15296.0 | 10.732 | 1 | .001 |

| C | Middle high | 79 | 2440.0 | 1922.0 | 220.0 | 16126.0 | ||||

| 10 | A | Middle low | 120 | 3438.2 | 2494.5 | 101.0 | 29083.0 | 17.303 | 1 | .000 |

| B | Middle low | 142 | 1624.1 | 1177.0 | 17.0 | 6054.0 | ||||

Percentage of coincidence between school attended and school closest to home by FGU.

| FGU | School | Yes | No | Total Yes | Total No | FGU | School | Yes | No | Total Yes | Total No |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | 5.9 | 94.1 | 9.8 | 90.2 | 6 | A | 2.4 | 97.6 | 5.8 | 94.2 |

| B | 10.2 | 89.8 | B | 8.1 | 91.9 | ||||||

| 2 | A | 4.7 | 95.3 | 2.1 | 97.9 | 7 | A | 3.4 | 96.6 | 1.9 | 98.1 |

| B | 0 | 100.0 | B | 0 | 100.0 | ||||||

| 3 | A | 0 | 100.0 | 2.7 | 97.3 | 8 | A | 74.5 | 25.5 | 33.9 | 66.1 |

| B | 4.8 | 95.2 | B | 5.5 | 94.5 | ||||||

| 4 | A | 19.0 | 81.0 | 22.8 | 77.2 | 9 | A | 0 | 100.0 | 0 | 100.0 |

| B | 25.7 | 74.3 | B | 0 | 100.0 | ||||||

| 5 | A | 17.1 | 82.9 | 18.5 | 81.5 | 10 | A | 28.3 | 71.7 | 17.9 | 82.1 |

| B | 11.5 | 88.5 | B | 9.2 | 90.8 | ||||||

| D | 27.1 | 72.9 | Total | 11.7 | 88.3 | ||||||

Descriptive and Contrast Statistics variable distance home–school by type of school.

| Type of school | N | Mead | Median | Min. | Max. | Kruskal — Wallis Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chi2 | df | Asympt. Sig. | ||||||

| Municipal | 859 | 2279.4 | 1274.0 | 35.0 | 29083.0 | 39.668 | 2 | .000 |

| Voucher private | 654 | 2608.2 | 1410.5 | 17.0 | 23508.0 | |||

| Non subsidized private | 135 | 3568.8 | 2638.0 | 186.0 | 21950.0 | |||

Descriptive Statistics variable distance home-school by income quintiles.

| Q. | N | Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | Percentiles | Kruskal –Wallis test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 25 | 50 | Chi2 | df | Asympt. Sig. | ||||||

| I | 274 | 1654.4 | 2517.1 | 40.0 | 28284.0 | 492.5 | 978.5 | 2006.0 | 132.2 | 4 | .000 |

| II | 385 | 2087.3 | 2889.1 | 29.0 | 29083.0 | 619.0 | 123.0 | 2545.0 | |||

| III | 374 | 2475.1 | 3242.4 | 17.0 | 25759.0 | 718.8 | 1339.5 | 2843.8 | |||

| IV | 192 | 3071.7 | 3264.1 | 141.0 | 17111.0 | 955.3 | 2247.0 | 3685.3 | |||

| V | 388 | 3478.8 | 3481.4 | 101.0 | 23508.0 | 1188.0 | 2522.0 | 4206.5 | |||

During the military government, a comprehensive reform was carried out. This reform included, among other areas, the educational area. In this way, the financing system of per student subsidy, which was the heir of Milton Friedman's voucher or school checks proposal, was adopted. This system, albeit reformed, is still in effect. It consists in the State delivering the same amount of money per student attending state or subsidized private schools, which would grant the families the right to choose schools. The expectation was that, in a context of competition under equal conditions, subsidized private schools would show a considerably higher quality than state schools. However, the accumulated evidence does not confirm that theory. On the contrary, a variety of studies points out that the main effect of the implementation of this system has been social segmentation (Hsieh & Urquiola, 2006; Mc Ewan, Urquiola & Vegas, 2008).

In addition, there are private schools that are not granted state funding, i.e. completely financed by the families.

At a state level, schools concentrate 37% of the system's students, whereas subsidized private schools and non-subsidized private schools concentrate 55% and 7%, respectively.

“Residential segregation in Chile (at least in big conurbations) is considerable and schools, especially during early ages, tend to attract students close to them, geographically speaking. Not surprisingly, part of the segregation observed at a school level is merely a reflection of territorial segregation” (Hernando et al., 2014:29).

Since 2007, a centralized system—Transantiago —has been operating. This system is financed by the State and has fixed routes, stops and fares. In addition, it is managed by large private companies that replaced the small independent companies that set fares autonomously in the former system

Since Sheller and Urry's (2006) seminal study, mobility has been addressed in connection with international migrations or daily trips in the urban space, as a new paradigm that would provide an explanation for the territorial complexity of the globalized world (Kwan & Schwanen, 2016). Without minimizing the importance of this perspective, Latin-American studies propose to consider, from a Marxist perspective, mobility a cultural variant of a renewed territoriality defined by the current capitalism (Ramirez Velázquez, 2013).

Jirón et al. (2010: 24) define urban daily mobility as “a social practice of daily movement through urban space and time, which grants access to activities, people and places”.

The FGU has been determined with a one-kilometerin diameter buffer, considering the distance defined as “walkable” by the specialized literature (Munizaga & Palma, 2012).

In the case of one school, data was obtained from administrative records (35 cases)

Education Quality Measurement System (simce, in Spanish) is a standardized evaluation of census nature that is annually applied to students at different educational levels. Besides collecting information to evaluate students’ learning of curricula content and skills, this test gathers data regarding teachers, students and parents.