This paper deals with the impact of ‘early’ nineteenth-century globalization (c. 1815–1860) on foreign trade in the Southern Cone (SC). Most of the evidence is drawn from bilateral trades between Britain and the SC, at a time when Britain was the main commercial partner of the new republics. The main conclusion drawn is that early globalization had a positive impact on foreign trade in the SC, and this was due to: improvements in the SC's terms of trade during this period; the SC's per capita consumption of textiles (the main commodity traded on world markets at that time) increased substantially during this period, at a time when clothing was one of the main items of SC household budgets. British merchants brought with them capital, shipping, insurance, and also facilitated the formation of vast global networks, which further promoted the SC's exports to a wider range of outlets.

Este artículo trata sobe el impacto de la globalización temprana de comienzos del siglo XIX en el comercio exterior del Cono Sur (CS). La mayor parte de la evidencia proviene de flujos de comercio bilateral entre el Reino Unido y el CS en tiempos en que aquel era el principal socio comercial del CS. La principal conclusión de este artículo es que la globalización temprana tuvo un impacto positivo en el comercio exterior del CS debido a lo siguiente: los términos de intercambio del CS con el Reino Unido mejoraron durante este período; el consumo per cápita de textiles del CS aumentó sustancialmente durante este período, en tiempos en que los textiles eran la principal manufactura comercializada a nivel mundial y los mismos constituían uno de los principales componentes del gasto de los hogares en el CS. Comerciantes británicos aportaron capital, seguros, su marina mercante y facilitaron la creación de grandes redes comerciales globales, todo lo cual promovió aun más el comercio exterior del CS.

This paper deals with the impact of ‘early’ nineteenth-century globalization (c. 1815–1860) on foreign trade in the Southern Cone. At the beginning of this period, mainly due to the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the collapse of the Spanish American Empire, there was a significant increase in the worldwide trade interconnections of the region and its overall volume of foreign trade. Indeed, the volume of international trade in the former Spanish American empire increased beyond all previous levels, as did the multilateralism of Latin America's foreign trade. The newly independent territories opened up their ports to direct and legal trade with all nations, thus removing all colonial restrictions on trade. From the 1810s onwards, foreign (non-Spanish) merchants established themselves in the new republics for the very first time,1 bringing with them their wide range of international connections and more advanced commercial practices than the old Spanish masters used.

When considering whether or not globalization benefited both rich and poor nations in the past (and to what extent), the extant literature on the impact of nineteenth century globalization (i.e. negative or positive) on peripheral regions’ foreign trade is not only thin but also divided. For example, supporters stress the positive gains from trade, while detractors stress the negative impact of globalization on the poor periphery through primary product price volatility and de-industrialisation.2 Regarding this controversy, I will argue here that, as far as international trade is concerned, the first decades after the Southern Cone gained independence were beneficial to this peripheral region.

To demonstrate this point I will provide an analysis of the bilateral trade between Britain (the main trading partner of the Southern Cone during this period) and Chile and the River Plate provinces (nowadays Argentina and Uruguay). The point is to stress the positive gains for the new republics of trading directly and legally with Britain, and when not directly with Britain with other outlets supported by British merchants’ networks. Namely, there was an improvement in the terms of trade between the Southern Cone and Britain; linked to this factor, the Southern Cone's per capita consumption of textiles (the main manufacture traded on world markets at that time) increased substantially during this period, at a time when clothing was a staple item of Latin American household budgets. British merchants brought with them capital, shipping, insurance, and advanced merchant practices which could only have promoted the foreign trade of this region; and British merchants also provided their vast global networks, which further promoted exports from the Southern Cone to a wider range of outlets.

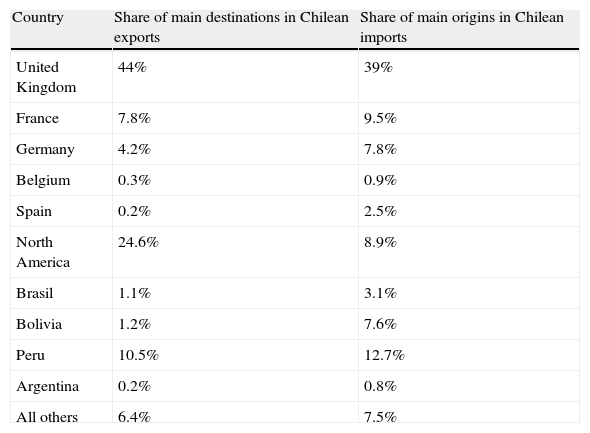

I am aware that a full assessment of the impact of globalization on international trade in the Southern Cone should consider all foreign trade in the Southern Cone, or at least trade with other important regions beyond Britain (i.e. continental Europe, intra-regional trades and the United States), but alas that data is not readily available for most of the period under study. Nonetheless, as the Steins have already highlighted, the great value of the Anglo-Latin American trade statistics is that they are one of the most reliable indexes of Latin America's economic activity during the first half of the century (Stein & Stein, 1980, p. 136). Indeed they are so reliable that the widely quoted terms of trade between Latin America and the rest of the world during the first half of the nineteenth century use British export data as a proxy for Latin American imports, but note that ‘this approach is undesirable if the composition of British exports is unrepresentative of the imports of developing countries as a whole’ (Williamson, 2008, p. 388). However, in this case Britain was indeed the main commercial partner of the new republics. In the case of Chile for example, for the earliest period for which there is data available on Chilean exports and imports per destination and origin, that is 1844–1849, the share of the United Kingdom within Chilean exports and imports was 44% and 39%, respectively, well ahead all other partners (Table 1).

Shares of main destinations and origins within Chilean exports of Chilean produce and imports for national consumption, 1844–1849.

| Country | Share of main destinations in Chilean exports | Share of main origins in Chilean imports |

| United Kingdom | 44% | 39% |

| France | 7.8% | 9.5% |

| Germany | 4.2% | 7.8% |

| Belgium | 0.3% | 0.9% |

| Spain | 0.2% | 2.5% |

| North America | 24.6% | 8.9% |

| Brasil | 1.1% | 3.1% |

| Bolivia | 1.2% | 7.6% |

| Peru | 10.5% | 12.7% |

| Argentina | 0.2% | 0.8% |

| All others | 6.4% | 7.5% |

Source: Estadística Comercial de Chile, 1844–1850.

By now readers may have asked themselves two questions: Why this period in particular? Why only the Southern Cone and not the whole of Latin America? First, the period under consideration is under-researched in international trade (if compared to the post 1870 epoch), in particular from a Latin American point of view. Williamson rightly highlights the fact that ‘Latin American economic performance is better documented between mid-century and the Great War in Europe’.3 That is, this paper sheds new light not only on the broader topic of the impact of globalization on the periphery, but also on Latin American economic history during the first half of the nineteenth century. Second, to assess the whole of Latin America would be a Herculean task beyond the scope of this paper. The intention of concentrating in the Southern Cone was to enable me to build a comprehensive trade database at the most detailed possible level. This would have taken me several years of data collection if the whole of Latin America were included. In addition, by selecting two specific outlets (Chile and the River Plate provinces), it was intended to avoid a paper that was littered with generalisations, always a risky exercise given the heterogeneity of the region.

After this introduction, this article contains two other sections. In the next section I consider the nature of Anglo-Latin American trade statistics available to us, which are the main source of information used in this paper. The last (and core) section concerns the impact of ‘early’ nineteenth-century globalization on foreign trade in the Southern Cone, and it first analyses the terms of trade with Britain and the price volatility of the produce exported from the Southern Cone. The section then deals with the Southern Cone's consumption of British textiles and with the exports to pay for them, after which British merchants’ assets promoting trade in the Southern Cone are discussed. Finally, the section analyses the British merchants’ global networks and their contribution to the region's foreign trade.

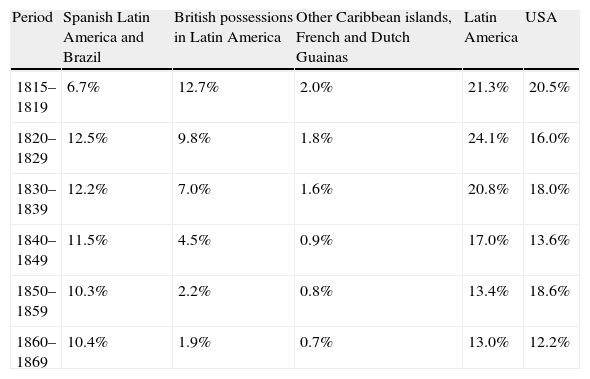

2Anglo-Latin American trade c. 1815–1870: preliminary remarksGiven the fact that this paper relies heavily on British statistics for Anglo-Latin American trade, two preliminary remarks about these statistics seem pertinent before addressing the main concern of this article (i.e. whether early globalization was beneficial or not for international trade in the Southern Cone). First, in a recent publication (Llorca-Jaña, 2012, chapter 2), based on new data it is shown that British exports to Latin America were very important during the 1810–1840s, contrary to widely held views on British exports to that region.4 This new data shows that Latin America as a whole took between 17% and 24% of Britain's world exports during the 1810–1840s and some 13% during the next two decades (Table 2). Taking a fifth (1830s) and nearly a quarter (1820s) of the value of the world exports of the principal industrial power of that time is certainly an indication of the importance of Latin America as an outlet for British manufactures during this early period. And indeed, it is difficult to reconcile these numbers with the specific claim that Latin America ‘failed to benefit from the boom in world trade between 1820 and 1870’ (Bates et al., 2007, p. 929). Furthermore, Table 2 suggests that early nineteenth-century globalization could not have been detrimental to foreign trade in Latin America.

Latin America's shares in world exports from the United Kingdom, 1815–1869. Shares from declared value series.

| Period | Spanish Latin America and Brazil | British possessions in Latin America | Other Caribbean islands, French and Dutch Guainas | Latin America | USA |

| 1815–1819 | 6.7% | 12.7% | 2.0% | 21.3% | 20.5% |

| 1820–1829 | 12.5% | 9.8% | 1.8% | 24.1% | 16.0% |

| 1830–1839 | 12.2% | 7.0% | 1.6% | 20.8% | 18.0% |

| 1840–1849 | 11.5% | 4.5% | 0.9% | 17.0% | 13.6% |

| 1850–1859 | 10.3% | 2.2% | 0.8% | 13.4% | 18.6% |

| 1860–1869 | 10.4% | 1.9% | 0.7% | 13.0% | 12.2% |

Source: Llorca-Jaña (2012, Table 2.5).

Indeed, these new figures also support the idea that Latin America's economic performance during this period was not as bad as many have previously thought. Before this data was available, the prevailing (and negative) approach regarding British exports to Latin America after independence could be seen within a more broadly pessimistic picture about the performance of most Latin American economies during the first half of the nineteenth century. For many economic historians, this period is seen in terms of ‘lost decades’ for the region. They argue that ‘independence was followed by political instability, violent conflict, and economic stagnation lasting for about a half-century’, concluding that ‘economic performance in the half-century after independence was abysmal … Lost decades indeed’.5

That the region, including the Southern Cone, suffered a great deal of political instability and violent conflict is beyond question. Yet, the idea that it suffered half a century of economic stagnation has recently been challenged, mainly by Prados de la Escosura, who argues that per capita GDP experienced growth in the region during this period; that there was an improvement in the net barter terms of trade (and therefore in the purchasing power of exports);6 and that per capita exports increased.7 Finally, according to Prados de la Escosura, one explanation of this received and negative (albeit unfair) view of the economic performance of Latin America after independence is that ‘the historical literature has employed the United States as the yardstick to measure Latin American achievements’.8 More recently, other authors such as Tena and Federico, Newland, Poulson and Gelman (for the Argentine case) have provided further evidence to sustain a more optimistic view on Latin American economic performance after independence.9

Following Prados de la Escosura, it seems apparent that to pay for the massive share of British world exports shown in Table 2 Latin America ought to have performed well enough to give Britain something in exchange, in particular at a time when, apart from British loans in the 1820s, little more was lent to Latin America before the 1860s. Likewise, direct foreign investment during this period was unimportant and, therefore, Latin American imports could not have been funded by international borrowing during this period. Consequently, the data provided in Table 2 gives additional support to Prados de la Escosura's and other scholars’ more recent and positive views about this period for the region, thus making an important contribution to this debate. Indeed, Prados de la Escosura provided evidence of Latin American per capita exports growing during this period, but did not consider per capita imports (a point treated in depth below). In this same vein, Tena and Federico recent work on Latin American export performance after 1820 does not include Latin American imports because the authors recognised that ‘the literature on Latin American trade integration is more concerned’ with exports (Tena & Federico, 2011, p. 7).

Before going any further, the second point worth making about British exports to Latin America is that between 1815 and 1869 textiles were the principal object of trade and indeed dominated the market. For example, in the case of the Southern Cone, textiles accounted for over 80% of British exports there during 1815–1859, a point well illustrated in Fig. 1. That is, any in-depth analysis of British exports to any Latin American outlet during the early nineteenth century should focus on textiles, and in particular on volumes exported given the falling export prices of British textiles during this period (as shown in Fig. 3).

United Kingdom exports to the Southern Cone, 1815–1869. Annual averages in declared value (£000). Source: Llorca-Jaña (2009, Figure 1).

Finally, regarding the British trade data presented in this paper, it is worth noting that in relation to values, the series used was ‘declared values’, because this is a fairly accurate statement of the real value of British exports, which cannot be said about the ‘official values’ series because the prices it uses are fixed and therefore obsolete. In relation to volumes, the indexes of quantum were constructed by adding all volumes (in yards) for all products within each broad category: wool manufactures, cottons and linens. It is estimated that a total of approximately 20,000 numerical data were entered. Therefore, diverse filters in Excel to test the validity of the figures being entered were employed during fieldwork.10

3The impact of ‘early’ nineteenth-century globalization on foreign trade in the Southern ConeI will now proceed to discuss the impact of ‘early’ nineteenth century globalization on foreign trade in the new republics of the Southern Cone. In order to do so, I shall initially provide an analysis of the terms of trade, followed by the development of the Southern Cone's consumption of British manufactures (and the exports from the Southern Cone which paid for these imports), continue with the importance of British ‘invisible’ and visible assets that were further promoting the Southern Cone's external trade, and end by discussing the global trade networks brought by British merchants to the Southern Cone after independence.

3.1Terms of trade with Britain and price volatility of produce exported from the Southern ConeUntil recently there was little literature on Latin American terms of trade for individual countries during the first decades after independence, and even less on the impact of early globalization on them. However, as is highlighted by Bértola and Williamson,11 Prebisch's and Singer's works published during the early 1950s had long led scholars to believe that the collapse of primary product prices (in particular in relation to manufactures) witnessed during the 1929 Great Depression was a downward secular trend which originated after independence. In turn, this continuous and persistent deterioration of the terms of trade (what has come to be known as the Prebisch–Singer hypothesis) was seen by many as a key element limiting the development of the region, given that most countries specialized in the production and export of a handful of primary products, although this debate remains open.12 Yet, the idea of a deterioration of the region's terms of trade during the 1810–1850s has been recently refuted by many authors. For example, for Bulmer-Thomas, export growth after independence ‘appears to have been accompanied by a secular improvement in the net barter terms of trade’ (Bulmer Thomas, 2003, pp. 37-38 and 78-79), although he provides evidence for Brazil only. Williamson also claimed that ‘the secular price boom was huge in the poor periphery: between the half-decades 1796–1800 and 1856–1860, the terms of trade increased by almost two and a half times’, although for Latin America in particular the ‘boom up to 1860 was much more modest … [and] there was very little change at all in the Latin American terms of trade between about 1830 and 1870’.13 In the cases of Chile and Argentina, Prados de la Escosura reached two similar conclusions. First, that in relation to the net barter terms of trade between the new republics and the rest of the world from independence and until the mid-nineteenth century, for Chile ‘stability was the rule’, and that ‘Argentina's terms of trade showed an improvement that peaked in the late 1850s’ (Prados de la Escosura, 2009, p. 289). Second, that the purchasing power of per capita exports increased significantly for Chile and Argentina c. 1830–1850.14

These conclusions are further supported by my new data on Anglo-Southern Cone trade, which even provide a more positive account of the Southern Cone's terms of trade with Britain. The prices of the main Southern Cone products imported by Britain during the first half of the nineteenth century (i.e. Chilean copper and hides from the River Plate)15 remained relatively stable during c. 1815–1840 and subsequently fell at a much slower rate than Britain's export prices for textiles (when textiles were the main British export to the Southern Cone), as can be seen in Fig. 2. That is, there was no major volatility in the prices of the main export products of the new republics. At the same time, British textile export prices declined sharply during this period. Export prices for cottons fell to such an extent that in the 1850s cottons fetched a quarter of the value at which they had been sold in the late 1810s. Prices for plain linens fell by nearly 50% over a comparable period. Likewise, prices for wool manufactures mixed with cotton (the most important wool manufacture exported to the Southern Cone) also fell dramatically, as seen in Fig. 3.As a consequence of the developments portrayed in Figs. 2 and 3, relatively speaking, the prices of the principal Southern Cone commodities increased substantially compared to British textiles during most of the period between 1815 and 1856. This suggests that the terms of trade improved significantly for Chilean and River Plate native merchants, as well as for most of Latin America, as was previously found by Newland, Williamson and other scholars in relation to Argentina (Newland, 1998, Table 2; Newland & Poulson, 1998, p. 327; Salvatore & Newland, 2003, p. 20; Bértola & Williamson, 2006, p. 34), Latin America,16 and more generally with regard to most of the primary-product-producing periphery (Williamson, 2008, p. 356). This was already a known development,17 although no precise numbers existed for bilateral trades between Britain and the Southern Cone during this period.

London prices for copper and hides from the Southern Cone, 1815–1856. Indexes where 1815=100. Source: For hides, London New Price Current; Halperín-Donghi (1963); and London Mercantile Price Current. For copper, Mulhall (1899).

Selected United Kingdom textile export prices to the Southern Cone. Indexes where 1815=100, built from series originally in pence per yard, 1815–1879. Source: Adapted from Llorca-Jaña (2012, Figure 7.2).

Fig. 4 illustrates accurately the point being made for our specific case study in a very simple way.18 In 1836, the relative prices of both Chilean copper and River Plate hides to British printed cottons (the main British staple) had improved around 200% if compared to the prices of 1815 and, by the mid-1850s, by over 400% if compared to the prices at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, although it is true that the latest growth was a short-term phenomenon. In any case, between the mid-1830s and the mid-1850s, native merchants in the Southern Cone offering copper and hides in the market exchanged their local produce for two to four times more yards of British printed cottons than they would have received at the comparable prices of the late 1810s. Yet, as was previously highlighted by Salvatore and Newland, during the 1840s, because of a drastic decline in the export prices of hides, there was a temporary deterioration of the terms of trade for Argentina.19

Relative prices of the main Southern Cone staples to British printed cottons exported to the Southern Cone, 1815–1856. Source: Llorca-Jaña (2012, Figure 7.4).

Although not related to the main focus of this article, it would be pertinent to mention that there is an interesting debate led by Williamson on whether or not the improvement of the terms of trade observed for underdeveloped countries could have impaired their chances of industrialisation during the period dealt with in this essay. According to Williamson, the improvement of the terms of trade experienced by the periphery before 1850 fostered de-industrialisation, to the extent that it must have contributed significantly to the Great Divergence (Williamson, 2008, pp. 357-358). This is not the place to solve this debate, but Williamson's thesis does not seem to fit Chile's experience. Indeed, copper smelting (i.e. an industrial activity, albeit unsophisticated) became important after the 1830s, when reverberatory furnaces and other techniques were widely introduced in the country. Overall, the national smelting industry was consolidated by the middle of the century. During 1844–49, bars accounted for 60% of the Chilean copper production. Around this time Chile's smelting capacity was second only to that of Britain (Valenzuela, 1992, p. 509).

3.2The Southern Cone's consumption of British textiles and exports to pay for themThe sole improvement in the terms of trade between the Southern Cone and Britain suggests, ceteris paribus, that the volume of Southern Cone's per capita imports of British manufactures should have increased during this period. Furthermore, Prados de la Escosura collected evidence of the Southern Cone's per capita exports growth during the first half of the nineteenth century. In addition, Prados de la Escosura concluded that Chilean per capita GDP increased importantly, in particular after 1830, and ‘available economic indicators suggest fast growth in the Buenos Aires region … [which was] translated into an improvement in Argentina's per capita income’ too (Prados de la Escosura, 2009, p. 299). Based on all these conclusions you would expect an important increase in the Southern Cone's national consumption, including the consumption of British manufactures. However, economic historians have said nothing about the Southern Cone's per capita imports of manufactures during the first half of the nineteenth century. This is not surprising: Latin American imports have for long remained an unexplored topic.20

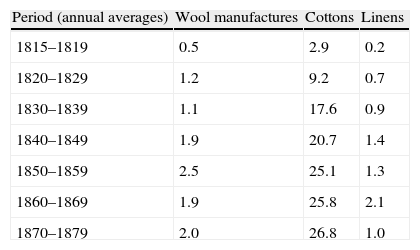

Yet, my new evidence shows that British exports to the Southern Cone grew at very high rates, especially if volumes are considered. As a consequence of this, the population of the Southern Cone managed significantly to increase the per capita consumption of textiles (Table 3), at a time when clothing was a staple item of Latin American household budgets and the main manufacture imported by the region. In per capita terms, during the 1840s, the River Plate provinces and Chile consumed seven times more yards of British cottons and linens than in the late 1810s and nearly four times more yards of British wool manufactures. Indeed, up to the late 1850s there was a massive expansion of the per capita consumption of British textiles (Fig. 5).

Southern Cone per capita textile imports (volume) from the United Kingdom, 1815–1879, annual average yards imported per inhabitant.

| Period (annual averages) | Wool manufactures | Cottons | Linens |

| 1815–1819 | 0.5 | 2.9 | 0.2 |

| 1820–1829 | 1.2 | 9.2 | 0.7 |

| 1830–1839 | 1.1 | 17.6 | 0.9 |

| 1840–1849 | 1.9 | 20.7 | 1.4 |

| 1850–1859 | 2.5 | 25.1 | 1.3 |

| 1860–1869 | 1.9 | 25.8 | 2.1 |

| 1870–1879 | 2.0 | 26.8 | 1.0 |

Source: Llorca-Jaña (2012, Table 2.4).

Southern Cone percapita consumption of British textiles (cottons, wool manufactures and linens), index of quantity, 1840=100. As in Table 3, this figure considers total imports by the Southern Cone, and therefore the population of Argentina, Uruguay and Chile. Source: Llorca-Jaña (2012, Figure 9.1).

No stagnated economy behaves this way, and this positive consumer behaviour does not belong to inhabitants of a region showing an ‘abysmal’ economic performance, as many previously believed.21 On the contrary, this increase in the consumption of British textiles is in line with the idea of a growing per capita GDP in the region, already highlighted by Prados de la Escosura and others with him. Finally, if imports from Britain grew so did the Southern Cone's exports to Britain (or elsewhere) which paid for these imports, though this needs to be proven too. As far as Chile is concerned, after independence exports of silver increased significantly, especially from the 1830s. During the 1820s Chile was (legally) exporting some £200,000–£250,000 annually to the world in gold and silver (much of which went to Britain), but by the mid-nineteenth century this figure had increased to over £0.5m per annum (an amount excluding contraband and legal re-exports) (Llorca-Jaña, 2012, Chapter 6). Regarding Britain in particular, by the mid-1840s Chile was already sending over £0.45m in gold and silver per annum. Likewise, Chilean copper production and exports were also on the increase from the early nineteenth century until the 1870s.

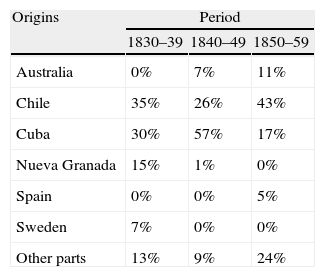

Fig. 6 shows this development until 1859: Chilean copper exports (in volume) had increased roughly nine fold between independence and 1859, and much of the copper ended up in Britain. Indeed, during the 1830–1850s, Chile and Cuba were the main suppliers of copper for the British market, as shown in Table 4. During the 1850s in particular Chile was well ahead of all other copper suppliers for the British market. These products (i.e. copper and silver) were, in turn, the main pillars upon which the Chilean economy rested during the first half of the century: Chile had been favoured in the commodity lottery raffle (at least for a while).

Chilean copper production (and exports). Annual averages, 1801–1859 (000 tons). Source: Herrmann (1894) and Braun et al. (2000).

UK's imports of copper per main origins, 1830–1859 (shares from tons).a

| Origins | Period | ||

| 1830–39 | 1840–49 | 1850–59 | |

| Australia | 0% | 7% | 11% |

| Chile | 35% | 26% | 43% |

| Cuba | 30% | 57% | 17% |

| Nueva Granada | 15% | 1% | 0% |

| Spain | 0% | 0% | 5% |

| Sweden | 7% | 0% | 0% |

| Other parts | 13% | 9% | 24% |

Source: Own estimates from British Parliamentary Papers, several volumes.

Likewise, with regard to Argentina, exports of hides, jerked beef and tallow also increased after the 1810s to such an extent that it is estimated that Argentina's total exports of produce to the world grew at the staggering rate of 4–5% per annum for the period 1810–1850 (Salvatore & Newland, 2003, pp. 21-22; Bulmer Thomas, 2003, pp. 35-36). For hides in particular (the star River Plate product during the period dealt with in this paper), a recent work has shown that adding together Buenos Aires and Montevideo, hides exported from the River Plate to the world amounted to about 1 million units during 1817–1841 and to over two million during 1842–1860.22 For the British market in particular, data on import volumes shows that the River Plate was the main supplier of untanned hides to Britain during our period of study and that Britain was taking increasing volumes of this product (Fig. 7). Indeed, soon after independence, River Plate hides found a ready market in Britain in sufficient volumes to pay for most British imports. In the words of Parish, the first British consul in the area: ‘Buenos Ayres possesses in her hides, a vast and increasing means of returns for all the commodities the population of these provinces are likely to want from Europe’.23

United Kingdom imports of untanned hides, 1815–1869. Annual averages per main origins (thousands of cwt). Source: Llorca-Jaña (2012, Figure 6.3).

Overall, the significant Southern Cone's increase in consumption of British textiles is certainly in line with Prados de la Escosura's findings that the Southern Cone's per capita exports grew and that the ratio exports/GDP increased for both Chile and Argentina between 1830 and 1850 (Prados de la Escosura, 2009, p. 294). That is, globalization does not seem to have been harmful to the Southern Cone: rather the opposite, at least as far as both its consumption of British manufactures and its export performance are concerned.

3.3British merchants’ ‘invisible’ and visible assets promoting trade in the Southern Cone: insurances, shipping and communicationsNot only was the population of the new republics able to buy more clothing with less of their own produce, but the republics’ foreign trade also benefited from having access to a new marine insurance market introduced by British and other European merchants. The role of the insurance industry in promoting Latin American imports and exports during the first half of the nineteenth century has been radically underestimated by the historiography, despite recent advances in our knowledge of this subject (Llorca-Jaña, 2010, 2011c). This is not surprising; after all international insurance history is an emerging field (Pearson, 2010, pp. 21-23).

What is clear, though, is that in the 1810s, when independence was gained, there was no national marine insurance market in the Southern Cone. The marine insurances behind most of the Southern Cone's imports and exports were affected in Britain, even for trades that never touched on British ports.24 Without the London insurance market the risks associated with foreign trade in the Southern Cone would have been much higher and undoubtedly the volume of trade would have been much lower. That is, the arrival of British (and other foreign) merchants in the Southern Cone, and with them their insurance facilities, could have only further promoted the region's foreign trade. The Southern Cone's new access to the well-developed London insurance markets is a clear consequence of the increasing worldwide interconnectedness developing after the 1810s, and its impact cannot be described as anything but positive for the new republics’ external trades. It was only in 1853, for example, that the first national insurance company was set up in Chile, and even that company resorted to the crucial support of British merchants for its creation. Likewise, in Argentina, the first national company after independence was launched as late as 1860.25

The new republics also gained important benefits from the massive improvements in transport and communications introduced by the British. The unimportant merchant fleets of the new republics could not possibly have coped with the increasing volumes of trade that followed after independence. It was thanks to the British and other countries’ merchant fleets that the bulk of the Southern Cone's exports left the region and imports arrived. In turn, these foreign merchant fleets introduced several improvements during early nineteenth-century globalization. For example, the British introduced iron into shipbuilding, which became very important from the 1840s onwards in promoting the Southern Cone's foreign trade.

Iron made hulls stronger which, for the vessels facing Cape Horn and the pampero winds off the River Plate, was extremely important for the protection of the merchandise being freighted. Iron was better than wood for resisting strain, tension and compression. Iron vessels had no equal in resisting bad weather and the regular action of waves. Because of this, iron vessels sprung fewer leaks and, therefore, fewer ‘particular averages’.26 They were also safer, more durable, cheaper to build and cheaper to repair. More importantly, iron allowed the building of bigger ships, and it is well known that larger vessels were cheaper to crew27 and, better still, also faster. All in all, sailing times were reduced by up to 50% between the 1810s and the late 1850s for trade between Chile and the United Kingdom (Llorca-Jaña, 2012, Chapter 7). Finally, the British also introduced better packing so as to protect their exports to distant markets such as the Southern Cone, which combined with more secure vessels lowered the costs of marine insurance (Fig. 8) by reducing the risks associated with exporting to Chile or the River Plate.28 This, again, was beneficial to the new republics since the cost of importing British manufactures further declined, as did the costs of exporting.

Premiums at Lloyds for shipments to Valparaiso (shillings per £100), 1822–1849. Source: Llorca-Jaña (2010, p. 34).

Likewise, as far as foreign trade is concerned, intelligence from the Southern Cone was conveyed in European means of transport. In turn, Europeans (mainly British) introduced several innovations in this area. The reduction in sailing times commented on above was not only due to bigger vessels, but also to advances in cartography, a better knowledge of winds, and a better use of oceanic currents. More importantly, European mail-packets connecting Europe with the Southern Cone were responsible for the establishment of a more efficient means of channelling information, people and express freights. This was all part of a major world postal development led by the British. Before the late 1830s, communications between the United Kingdom and the Southern Cone relied on letters carried by merchant sailing vessels, very often following indirect routes of communication. As a consequence, delivery times varied from 80 to 180 days; a postal embarrassment by later standards. If a Briton at Valparaiso wanted to send a letter to Liverpool, he was forced to rely on the services of merchant vessels. Steam mail packets changed all this.

Particularly important for our markets was the chartering of the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company (RMSPC) and the Pacific Steam Navigation Company (PSNC) in 1839 and 1840, respectively. The RMSPC first offered its services in 1842, covering the routes from the United Kingdom to the Caribbean ports, while the PSNC operated in the south Pacific. In 1846, the RMSPC extended its services to Panama, connecting at that point with the PSNC. At this moment, Chile became entirely ‘steam connected’ with the United Kingdom. Yet, the River Plate still depended on two sailing packets, one for the route United Kingdom–Rio de Janeiro and the other connecting Rio with the River Plate. So bad was communication under this system that letters sent from the River Plate to England waited on average for over 10 days in Rio before being despatched to Falmouth. In 1851, the RMSPC extended its services to the River Plate and, therefore, Britain and Buenos Aires became directly steam connected.

Furthermore, in 1855, when the railway across the Panama isthmus was completed, communications between Chile and the United Kingdom became even more rapid. Following these developments, postal delivery times were greatly reduced. For communications between Britain and the River Plate, during the 1810s and 1820s, as many as 80–120 days were usually taken to deliver a letter. In the 1830s, the average passage was 75–85 days, though direct-sailing vessels could undertake it in 65–75 days. With the extension of the RMSPC in the early 1850s, Britain was just 35–40 days away from the River Plate. For Chile, during the 1810s–1830s, the sailing passage usually took 120–180 days. The links between the PSNC and the RMSPC reduced postal times between England and Valparaiso to 75–80 days from the mid-1840s. The Panama railway cut the time by two weeks, so that delivery times between Liverpool and Valparaiso fell to around 60 days. Thereafter, postal deliveries were completed in just 45 days in the mid-1860s and in as little as 40 days by the early 1870s. That is, before telegraphic connections were introduced, speedier communications reduced postal delivery times by about two-thirds between the 1810s and the 1850s, which, including a return journey, meant a saving of over five months in total. This also had many other positive implications. For example, the transmission of bills of exchange and bills of lading could now be sent for arrival before the goods themselves. Needless to say, these were also advances introduced by foreigners as part of this increasing worldwide interconnectedness taking place after the Napoleonic Wars, and they did promote foreign trade in the Southern Cone.

Linked to communications are intercontinental transport costs. Yet, as important as shipping freight rates were during the first half of the century, it is unfortunate that there is not a single piece of scholarship dealing with the development of ocean freight rates in respect of Britain and emergent markets after the Napoleonic Wars before the mid-nineteenth century.29 There is general agreement that ‘the decline in international transport costs after midcentury was enormous’ (O’Rourke & Williamson, 1999, p. 35), and that this contributed significantly to a greater integration of Latin America into world markets (Williamson, 1999, p. 106; 2006b, pp. 10-11). But what happened before 1850 with British exports to the Southern Cone?

Unfortunately I could not find continuous data on freight rates between Britain and the Southern Cone from 1815 to 1850. However, within general works dealing with freight rates, Davis states that there was, from the early 1820s, ‘a brief phase of rapid decline, down to the end of the 1840s’, estimated at 55%.30 In another work, it is estimated that freight rates between Antwerp and Rio de Janeiro (a shorter distance than United Kingdom-Southern Cone) fell substantially between the late 1810s and the late 1820s (around 25%) and, thereafter, a greater reduction occurred, so that rates charged in 1842 were 50% lower than in c. 1819 (Schöller, 1951, pp. 522 and 540), all of which agrees with Davis's work and has been accepted by many.31

Following Davis and Schöller, I have collected some freight data for general cargoes from diverse sources. Starting during the late 1810s, freight rates charged to one of the first British houses operating in Buenos Aires from Great Britain to the River Plate were as high as £6–£9 per ton (Reber, 1978, p. 29). I could not find information for the 1820s, while, for the mid-1830s, rates charged varied from £3 to £4.5 per ton for cargoes sent from Liverpool to Valparaiso.32 For the 1840s, freight rates do not seem to have varied much as the few transactions I found ranged from £3.75 to £4.25 per ton.33 For the 1850s and early 1860s, rates charged varied from £3.5 to £4.5 per ton.34 Although this is not conclusive evidence, these data suggest that ocean freight rates for general cargoes from the United Kingdom to the Southern Cone declined significantly during the 1820s and early 1830s, as Davis and Schöller have suggested more generally, which further promoted trade between the Southern Cone and Europe during early nineteenth-century globalization. This was certainly beneficial to both Europe and Latin America. Indeed, the British consul in Valparaiso in 1852 once reported that ‘the distance from Europe is not now that formidable obstacle which formerly presented itself to the exportation of produce from Chile to that great mart; freights are now low’.35

3.4British merchants’ global networks and their contribution to the Southern Cone's foreign tradeBritish merchants who established themselves in the Southern Cone after independence brought with them their insurance connections, shipping facilities and channels of communications, which were undoubtedly positive contributions to the region's economies. They also brought with them capital, which was often essential for the local production of goods intended for export. Equally important, many of the foreign merchant houses that opened offices in the new republics after the demise of the Spanish empire brought with them a vast global network of contacts. These international networks promoted the growth of multilateral trade involving the Southern Cone, Britain and third parties, and of trade between the Southern Cone and two or more quarters of the world beyond Britain, and therefore the region's overall exports in better terms.

Thus, for example, many ‘new’ and important trades developed from Chile and the River Plate, and ‘old’ trades increased their importance. In both cases, British merchants’ global trading contacts and facilities (e.g. credit and insurances) could only have benefited the new republics’ foreign trade (exports in particular). The London merchant Huth & Co. is a case in point. In 1809, the founder of this house (trained in Hamburg and Corunna), emigrated from Spain to London. He established himself as a general commission merchant, trading mainly with northern Spain. In the 1820–1830s the business expanded and branch houses were opened in Chile, Peru and Liverpool, while agencies were opened in other British locations, as well as in Mexico, Buenos Aires, Germany and France. Building on this structure, by 1850 Huth had acquired the impressive capital of £0.5m and had dealings with about 2000 correspondents all over the world (Table 5), establishing an impressive global network of trade, insurance and lending.

Location of Huth's correspondents. A sample for 1846–1848.

| Country | Number of correspondents | Share | Country | Number of correspondents | Share |

| North America | 77 | 4.2% | United Kingdom | 324 | 17.5% |

| Mexico | 27 | 1.5% | England | 278 | 15.0% |

| USA | 50 | 2.7% | Northern Ireland | 8 | 0.4% |

| Scotland | 26 | 1.4% | |||

| Caribbean | 60 | 3.2% | Wales | 12 | 0.6% |

| Cuba | 44 | 2.4% | |||

| Haiti | 1 | 0.1% | Europe | 1216 | 65.7% |

| Jamaica | 2 | 0.1% | Austria | 19 | 1.0% |

| Puerto Rico | 6 | 0.3% | Belgium | 73 | 3.9% |

| Saint Thomas | 3 | 0.2% | Croatia | 1 | 0.1% |

| Saint Croix | 4 | 0.2% | Czech Republic | 6 | 0.3% |

| Denmark | 5 | 0.3% | |||

| South America | 63 | 3.4% | Finland | 5 | 0.3% |

| Argentina | 7 | 0.4% | France | 73 | 3.9% |

| Bolivia | 1 | 0.1% | Germany | 528 | 28.5% |

| Brazil | 22 | 1.2% | Gibraltar | 1 | 0.1% |

| Chile | 6 | 0.3% | Ireland | 4 | 0.2% |

| Colombia | 1 | 0.1% | Italy | 19 | 1.0% |

| Guyana | 1 | 0.1% | Latvia | 5 | 0.3% |

| Peru | 10 | 0.5% | Netherlands | 61 | 3.3% |

| Uruguay | 2 | 0.1% | Norway | 7 | 0.4% |

| Venezuela | 13 | 0.7% | Poland | 38 | 2.1% |

| Portugal | 4 | 0.2% | |||

| Asia | 60 | 3.2% | Russia | 11 | 0.6% |

| China | 12 | 0.6% | Spain | 226 | 12.2% |

| India | 40 | 2.2% | Sweden | 88 | 4.8% |

| Philippines | 4 | 0.2% | Switzerland | 40 | 2.2% |

| Singapore | 1 | 0.1% | Ukraine | 2 | 0.1% |

| Sri Lanka | 1 | 0.1% | |||

| Turkey | 2 | 0.1% | No available | 39 | 2.1% |

| Africa | 5 | 0.3% | Australia | 6 | 0.3% |

| Sierra Leone | 1 | 0.1% | |||

| South Africa | 4 | 0.2% | Grand total | 1850 | 100.0% |

Source: HPEL.

As far as the Southern Cone is concerned, it is well known that Huth, like many other British merchants, advanced capital to local producers of copper or hides, thus making an essential contribution to the export economy of the region. But thanks to Huth's branch in Chile, apart from cultivating local production and bilateral trades between Chile and Britain, interesting new trading networks were built connecting Chile and Britain with the USA, Asia and Europe. For instance, Chilean copper was sent not only to Britain to pay for British manufactures brought by Huth to Valparaiso, but also to the USA in exchange for textiles or to pay indirectly for British manufactures. Likewise, Chinese tea and silks were directly exchanged for Chilean silver and copper thanks to Huth's contacts in Asia, while Chilean wheat and flour were sent to Australia in payment for British manufactures involving complex multilateral trades.36

In a similar vein, Huth also promoted important intra-regional trades within the Americas connecting the Southern Cone. For example, Brazilian sugar was regularly sent to Huth's house in Chile,37 and Cuban tobacco to Valparaiso thanks to Huth's connections in Rio and Havana. Finally, it is worth noting that most of these operations involving Chilean imports and exports to and from places other than Britain were made possible thanks to Huth's extension of credit from London or Valparaiso to merchants in Asia, continental Europe or the USA. Likewise, these trade operations were very often insured by Huth in London even if these trades never touched on a British port, so that they made an important contribution to Chilean foreign trade.

In addition Adolphe Roux deserves a separate paragraph. In the early 1830s, Huth formalised a partnership with Roux of Paris,38 in order to supply the West Coast establishments with cottons, silks and other products directly from France or via Liverpool.39 In exchange, Roux received advances for part of these shipments. Roux was also an enthusiastic consumer of Chilean copper and silver, which were sent to him as remittances.40 But Roux was not the only merchant in continental Europe trading with Huth's houses in the Pacific. For example, Mayer & Fils (St Gall)41 also traded with Huth houses in the West Coast, as did Detmering from Bordeaux.

Another interesting connection which developed from the Pacific was with Rothschild. The Rothschilds were the sole buyers of Almadén's quicksilver from 1835, which gave them a powerful position within Latin American silver producing countries. Indeed, the Almadén mercury mines (Spain) were the main sources of the metal in the world at this time (Platt, 2012; Ferguson, 1999, pp. 358-362). Lacking agents in both Peru and Chile, which were important silver-producing countries, the Rothschilds decided to sell their quicksilver there through a house they could trust. The chosen one was Huth. From at least 1838, Huth was in charge of selling Rothschild's mercury in the West Coast.42 Remittances to Rothschild were in the form of silver bars or silver specie.43 Thus, Huth provided an essential service to Chilean silver producers, who did not have the means or connections to import directly from the Rothschilds.

Not having a branch in the River Plate did not stop Huth from doing business in that area. Indeed, the branches of the USA house of Zimmerman-Frazier at Montevideo and Buenos Aires were closely involved with Huth. Among many branches of trade, Zimmerman-Frazier provided hides for London, but also for Huth's friends in the USA and continental Europe.44 For example, Zimmerman-Frazier shipped hides to Bremen and drew against Huth.45 For this sort of operation, Huth was happy to make liberal advances.46 In the same vein, Huth promoted Zimmerman's shipments of jerked beef to Havana.47 Huth also provided these merchants with marine insurance services for divers trade operations,48 as he did with so many others in the region. Likewise, Zimmerman-Frazier imported textiles from Huth's friends in Britain and Germany.49 Beyond the sphere of trade, Huth was also a financial agent of Zimmerman-Frazier in London. Huth regularly received many bills of exchange drawn on numerous London merchants on Zimmerman's credit, for which Huth would negotiate acceptance. Zimmerman-Frazier also drew against Huth to clear its accounts with many other British merchants.

Other important correspondents in the River Plate were Hutz; Zevallos; Alfaro; and Sanchez. For example, Sanchez enjoyed an open credit with Huth that allowed him to ship hides to Madrid, thus further promoting Buenos Aires’ exports. Later on, Sanchez also started sending wool consignments to London, once Argentina started its production of wool for the international markets. Another company enjoying Huth's credit was Mohr & Ludovici. In this case, credit was opened in order to ship hides to Cologne.50 Both the credit made available by Huth to merchants in the River Plate and Huth's international networks of contacts were the pillars upon which many foreign traders in Buenos Aires and Montevideo relied in order to engage in international trade, thus showing the benefits of increasing worldwide interconnections during this period for the whole of the Southern Cone.

4ConclusionsI have shown that Latin America as a whole took between 17% and 24% of Britain's world exports during the 1810–1840s, and an important share of these exports went to the Southern Cone. Given that Britain was the principal industrial power at that time, this would suggest that early globalization would not have been detrimental to Latin America's foreign trade, and contradicts the idea that these were ‘lost decades’ for the subcontinent. These data provide support to Prados de la Escosura's, Tena and Federico's recent works on the subject, which argue that per capita GDP experienced growth in the region during this period; that there was an improvement in the net barter terms of trade; and that per capita exports increased.

In the case of the Southern Cone, this paper provides further evidence that during the first decades after independence there was an improvement in the Southern Cone's terms of trade with its main commercial partner of that time, namely Britain. This paper has also shown that the Southern Cone's per capita imports (therefore consumption) of British textiles increased systematically during the 1810s-1840s, at a time when clothing was one of the staple items of Latin American household budgets and the main manufacture imported by the region. Likewise, if imports grew so did the Southern Cone's exports which paid for these imports, for which I have provided further evidence. This is consistent with the idea of per capita GDP and per capita exports growing in the region during this period.

It could be argued that the Southern Cone was known to be one of the best performers, if not the best, within Latin America after independence. Nonetheless, you still have that scholars arguing that the first decades after independence were lost decades for the whole of Latin America do not exclude the Southern Cone from their conclusions. Likewise, those arguing that British exports to Latin America stagnated between the 1810s and the 1850s do not make any special case for the Southern Cone. They concluded that British exports to the whole region were unimportant and showed poor growth during the period covered by this paper.

I have also shown the gains made in foreign trade in the Southern Cone due to the invisible and visible assets brought by British merchants to the region. Indeed, the republics’ foreign trade benefited greatly from having access to a well-developed London insurance market. Furthermore, the improvements in transport and communications introduced by the British could only have promoted the region's external trade. Finally, British merchants also provided credit facilities unavailable in the region, which very often were an indispensable requirement for national production and facilitated engagement in international trade. Finally, drawing on a case study (Huth) I have shown the positive impact of British merchants’ global networks on foreign trade in the Southern Cone.

Furthermore, the case of Huth was not unique. After all, between 1810 and 1859 it is estimated that over 260 British merchant houses operated in the River Plate or Chile, and many more in the rest of Latin America (Llorca-Jaña, 2011a, Appendix 1). Some of these houses surely did not have such a vast international network of contacts as Huth did, but all of them combined together certainly promoted the Southern Cone's exports to many markets of the world, not only thanks to the contacts the British had everywhere, but also thanks to the credit, shipping and insurance facilities provided by these merchants or their connections all over the globe, at a time after the Napoleonic Wars when the number of British merchants was everywhere increasing. All these elements suggest that, as far as international commodity trade in the early nineteenth century is concerned, the impact of globalization was beneficial to foreign trade in the Southern Cone, and therefore the economies of that region.

FundingThis paper was funded by the ESRC (PTA-030-2005-00308), Fondecyt Chile (project 11100022) and Universitat Pompeu Fabra (Department of Economics & Business).

An earlier draft of this paper was presented at Trade, poverty and growth in history, a conference organized by A. Tena, G. Federico and J.G. Williamson, and a revised version at the World Economic History Congress (Stellenbosch). I am very grateful to Fundación Areces for funding my attendance to the first of these events. I am also very grateful to Antonio Tena for some comments to an earlier draft. Finally, I am also indebted to Phil Cottrell, Jorge Selaive, Rory Miller, Huw Bowen, Marcello Carmagnani, Bernard Attard, Katharine Wilson, Xavier Tafunell, Cristian Ducoing, Xabier Lamikiz, Mark Latham, and this journal's editors and referees.

See Llorca-Jaña (2011a) for more details of this topic.

For a general discussion of this topic, see Krugman and Venables (1995); Williamson (2006a, 2008); O’Rourke and Williamson (1999); Lindert and Williamson (2001).

Williamson (1999, p. 104). Elsewhere Williamson also lamented that, for example, it proved difficult for him to construct data on the terms of trade for Latin America for the pre-1870 epoch. Williamson (2006b, p. 17). On the lack of data of the economic performance of the region for this period see also Gelman (2009, p. 27).

Previously, it was widely believed that Latin America was not a tributary of the British economy during the 1810–1860s and that British exports to the region had stagnated during this period. Amongst many examples, see especially, Platt (1972), Miller (1993), Milne (2000), and Brown (2008). The problem was that Platt et al. did not produce any quantitative evidence to sustain their arguments. Indeed, no long-running series of British exports to Latin America was previously available: Platt's data, for example, only starts in 1850.

Bates et al. (2007, pp. 917 and 925), respectively. See also Coatsworth (1993, 1998) and Bértola and Williamson (2006, pp. 11–13).

It is worth noting that in Bates et al. (2007, p. 931), it is recognised that there was such an improvement, but that ‘Latin America had a less dramatic terms-of-trade boom than did the rest of the periphery’.

Prados de la Escosura (2009) has recently been challenged by Tena and Federico (2011), in the sense that per capita exports do not appear to have grown much between 1820–4 and 1850–4 for the whole of Latin America. However, for the particular case of Ibero-America, Tena and Federico do find that per capita exports increased importantly during this period (p. 11, Table 3).

Newland and Poulson (1998) and Gelman (2009) for Argentina and Tena and Federico (2011) for Ibero-America.

For further details on this, see Llorca-Jaña (2012, appendices B, C and D).

For a theoretical and recent discussion of this point, see Serrano and Pinilla (2011, pp. 214–216); Blattman et al. (2007, pp. 160–161); and Ocampo and Parra (2010, pp. 13–15).

Prados de la Escosura (2009, p. 293). Likewise, it was also known that Chilean per capita exports had increased importantly in the first half of the nineteenth century (Coatsworth, 1998, p. 33).

Chile's other main exports were silver and, to a lesser extent, gold, while the other main exports from the River Plate were tallow, silver and jerked beef. Of these, only silver, gold and tallow were sent to Britain. The prices of tallow in particular declined sharply between 1818 and the mid-1820s, but thereafter recovered quickly before the late 1820s and remained stable until the early 1850s. Own conclusions from London New Price Current (for 1815–1817) and Halperín-Donghi (1963) (for 1818–1852). If we were to treat silver like any other commodity, the price of silver in terms of gold also remained stable, in particular between the early 1820s and the late 1840s. For the whole period 1815–1860 the gold/silver price ratio oscillated between 15.11 and 15.95 (Warren and Pearson, 1933, p. 144).

It is estimated that ‘Latin American terms of trade increased by 1.7% per annum between 1820–1824 and 1855–1859’ (Williamson, 2006a, p. 83). See also Bulmer-Thomas (2003, pp. 38 and 78), Prados de la Escosura (2006, pp. 493–495), Coatsworth and Williamson (2004, p. 226), Williamson (2006b, pp. 11–12 and 26–27), Gelman (2009, p. 28).

In reference to the net barter terms of trade between Latin America and the rest of the world (which did not refer in particular to Britain nor apply exclusively to textiles), it has also been found that there were improvements in the terms of trade for both Argentina and Chile, although for the latter to a lesser extent (Prados de la Escosura, 2009, p. 289). Furthermore, the purchasing power of Argentinean exports increased eight times between 1830 and 1850, while Chile's purchasing power increased some 2.5 times during the same period (p. 293).

I am conscious of the fact that a more comprehensive terms-of-trade index could be built by incorporating the import and export prices of more products. Alas, there are no more series available of the Southern Cone's export prices to Britain (apart from tallow), while British export textile prices of other important products – apart from the one shown in Fig. 4, behaved in a similar fashion, so that including more textiles would not change the conclusions obtained from Fig. 4. In any case copper and hides were dominant within Southern Cone's exports. For example, it is estimated that horse's and cow's hides accounted for about 75% of all Argentine exports (Newland and Poulson, 1998, p. 327). Likewise, copper accounted for 40% of all Chilean exports during 1844–1859, followed by bullion and specie, in particular silver (25%) (Estadística Comercial, 1844–1860). Nonetheless, as argued above, the price of silver also remained stable, so it would not change our conclusions here.

Salvatore and Newland (2003, p. 21). Discussing Argentine terms of trade with the whole world (not only with Britain), these authors conclude that during c. 1830–1860, Argentina's terms of trade remained basically unchanged. That is, the evidence presented in Fig. 4 provides a more positive view than that of Salvatore and Newland. This could be because the import prices of Argentina for other products (non-textiles, and therefore unimportant in British exports to the River Plate) did not decline as much as British textile prices.

Orlove and Bauer (1997, p. 1). Take for instance, as an illustrative example, Bulmer-Thomas’ excellent survey (2003). The reader will find that in chapter 2, covering the period c. 1810–1850 (as this paper does), there is a section for ‘The export sector’, another for ‘The nonexport economy’, but there is nothing for Latin American ‘Imports’.

As stated in Bates et al. (2007, p. 925).

National Archives, London, UK, Foreign Office Correspondence (henceforth FO), FO 6/11, Parish to Canning (London). Buenos Aires, 25 August 1826.

Llorca-Jaña (2011c, Chapter 1) in particular.

Llorca-Jaña (2011c, Chapter 1, p. 25). Before independence a ‘national’ company operated for only a few years (between 1796 and 1802).

‘Particular averages’ happened when the goods arrived in a damaged state and the measure of the loss was the difference between the value of landing when sound and the value as damaged (Llorca-Jaña, 2011b, p. 17).

Shorter sailing times meant cost reductions associated with ship depreciation, victualling, wages and credit. Bigger vessels also increased the ratio of ‘ton of cargo per sailor’ which, in turn, further reduced labour costs. Furthermore, if compared to a similar wooden-hull ship, iron vessels had a greater stowage capacity because their shells were thinner. Finally, iron hulls, being lighter than wooden hulls, were also able to carry more produce (Llorca-Jaña, 2012, Chapter 7).

On this topic, see Llorca-Jaña (2011b).

The only exception would be Schöller (1951). Though, for the period before 1850 it contains data from Antwerp to Rio de Janeiro only (neither from Britain nor to the Southern Cone). Likewise, the widely quoted Oribe-Stemmer (1989) contains data mainly for the period after the 1880s (except for a few patchy figures for the mid-1850s).

Davis (1978, p. 179). For North (1958, p. 542), during the first half of the nineteenth century, there were freight reductions, but they were not as important as those suggested by Davis. Contrary to Davis and North, it has been said that ‘the general level of freight was essentially without trend until the mid-1860s’ (Harley, 1988, p. 315).

See for example Prados de la Escosura (2006, pp. 487–488).

Transactions recorded at the Huth Papers-English Letters (HPEL), University College London.

Ibid.

Transactions recorded at HPEL and Balfour Williamson Papers, University College London.

FO 16/79, Sulivan to Foreign Office (London). Valparaiso, 29 November 1852.

Guildhall Library, Huth papers (GLHP), MS 10700-6.

HPEL-26, Huth to Huth (London). Liverpool, 16 January 1839.

For the terms of the agreement, see HPEL-11. Huth to Roux (Valparaiso). London, 18 April 1833; GLHP, MS 10700-5, London, 1 June 1839.

HPEL-26, Huth to Huth (London). Liverpool, 2 March 1839.

HPEL-26, Huth to Huth (London). Liverpool, 15 February 1839.

HPEL-3, Huth to Mayer & Fils (St Gall). London, 20 January 1829.

Rothschild Archives, London (henceforth RHL). XI/38/149–50.

RHL-XI/38/149/A, Huth, Gruning & Co. to Rothschild. Valparaiso, 2 March 1841.

HPEL-31, Huth to Huth (Liverpool). London, 17 February 1841.

HPEL-9, Huth to Zimmerman-Frazier (Buenos Aires), London, 6 February 1832.

HPEL-6, Huth to Zimmerman-Frazier (Buenos Aires). London, 18 August 1830.

HPEL-14, Huth to Zimmerman-Frazier (Buenos Aires). London, 5 November 1835.