Immigration is a process that allows an individual to acquire capitals linked to attributes of education: knowledge, abilities, attitudes and values. Intrastate migration is a major phenomenon in Mexico that is dominated by women. In 2010, Yucatan was the state with the most internal movement. We applied a four-stage model to analyze migration among nine immigrant Maya women in Merida, the capital of Yucatan, during 2011. Semi-structured interviews were used to collect data. Using this theoretical basis and content analysis, we identified types of capitals and their relationship to attributes of education, and how the studied women had used them during their rural-to-urban migration. Emphasis was placed on the Instability and Establishment stages, and the adjustments they made in their new urban environment. Immigration is clearly an element of informal education that allowed the studied women to develop new decision-making skills and ways of appreciating themselves.

La migración es un proceso que permite al individuo adquirir capitales vinculados a los atributos de la educación: conocimientos, habilidades, actitudes y valores. La migración intra-estatal es un fenómeno importante en México dominado por las mujeres. En 2010, Yucatán tuvo la mayor migración interna. Utilizamos un modelo de cuatro etapas para analizar la migración de nueve mujeres inmigrantes mayas en Mérida, Yucatán, durante el año 2011. Empleamos entrevistas semi-estructuradas para obtener información. Con base teórica y análisis de contenido, identificamos tipos de capital y su relación con los atributos de la educación, y cómo las mujeres del estudio los utilizaron durante su migración rural a urbana. Hacemos hincapié en las etapas de Desequilibrio y Establecimiento y en los ajustes que realizaron en su nuevo entorno urbano. La inmigración es claramente un elemento de educación informal que permitió a las mujeres estudiadas desarrollar nuevas formas de apreciarse y habilidades para tomar decisiones.

Internal migration within Mexico has profound sociocultural and economic implications. In this study, we identify an informal education process to which immigrant Maya women are exposed in the city of Merida, Yucatan. Analyzing how it enriches their education is vital to better understanding the phenomenon of migration. Our analysis treats migration as a process involving actions that lead to personal changes caused by informal education.

Women who emigrate from rural to urban environments acquire and modify their cultural, human and social capitals (CK, HK and SK, respectively). They transform these into the tools they need to confront different life conditions as they interact with their new sociocultural and environmental surroundings. These capitals are closely linked to knowledge, abilities, attitudes, social values and relationships, all attributes of education (Argudín, 2005), and specifically of informal education (IE). We used the concept of capitals to identify the education acquired by women during a rural-to-urban migration process, and to analyze this process as an IE field.

To identify those IE attributes associated with migration and understand the life experiences of the participating women, we developed a four-stage model to distinguish how they acquired and modified their capitals before and after immigrating, and how they adjusted them to urban conditions. Use of the CK, HK and SK concepts was important because it allowed identification of the main education attributes present in each, and of how each constitutes an element of the IE that occurs during migration. We began by addressing the relationship between gender and migration, and the concepts of migration, education and capitals with the women who participated in the study.

The study's main aim was to analyze the acquisition, use and modification of CK, HK and SK as part of the IE process inherent to migration.

MigrationMigration within Mexico mainly involves women, whereas emigration from Mexico to other countries largely involves men. This difference is attributed to the costs, risks and benefits intrinsic to each kind of migration (Curran & Rivero-Fuentes, 2003).

Gender and migrationOver the last 40 years, gender and migration research has experienced three general phases. Between 1970 and 1985, interest in gender studies in Mexico first appeared and began to grow (Szasz, 1999). During this period, research focused on identifying differences in power relations, and emphasizing how actions, positions and privileges favored men. Studies highlighted how women were considered passive beings for whom men answered, and most analyzed the relationship between female migration, education and the labor market. Comparisons of education and income levels between men and women made it clear that income segregated the genders within the social dynamics of migration. Until gender studies developed as a discipline, gender had not been considered in studies of social relationships within the family, the labor market and migration. As it consolidated, from 1985 to 1995 (Ariza, 2007), the gender focus was applied to migration patterns, mainly by analyzing the domestic ambit. However, the discipline rarely addressed other areas where gender also plays a role, such as work, politics and consumer habits. Use of ethnographic methods with a gender focus helped to identify the conflicts and negotiations derived from male domination (Hondagneu-Sotelo, 2007). Immediately before and during this period, analyses began to be limited to interpretations linked mainly to economic destructuring, thus losing sight of women's role in other migration-related social processes. In the third phase (1995–2005), gender studies focused on the effects of migration on work, wages and women's domestic role. Analyses were also done of how migration alters social relationships by improving women's social position through their incorporation into the labor market and social networks (SN) (Ariza, 2007; Hondagneu-Sotelo, 2007).

The migration processThis process “involves a series of anticipated, planned and tested acts” (Du Toit, 1990: 308) in which those involved can explore opportunities, confront new situations or return to the starting point before remaining in a place other than the point of origin. We considered two models that treat migration as a process and identify its stages. The first is a psychological model proposed by Tabor and Milfont (2011) that allowed us to identify not only relevant aspects of the women's daily life and their towns, and their motivation to migrate, but also the sociocultural and environmental adaptation process linked to migration. The second model is a human ecological approach proposed by Lomnitz (1975) that emphasizes the adaptation to environmental and cultural changes associated with migration.

The psychological model was based on the Change Model of DiClemente and Prochaska (1982), and divides the migration process into four stages: pre-contemplation; contemplation; action; and acculturation. Pre-contemplation involves development of certain abilities − intrapersonal factors, strength and perseverance, an individual's links to SNs − but without considering the possibility of emigrating. Contemplation is when emigration is considered as a possibility. This can occur in response to an unexpected job offer and/or undesirable conditions in the place of origin and/or attractive conditions at the destination. This is when emigration options are analyzed. Action is the act of emigrating, and requires social support before departure, during migration and after arrival. Acculturation occurs in response to contact with the new culture at the destination. This is when psychological adjustments and sociocultural adaptation occur.

The ecological model involves three stages (Lomnitz, 1975): instability; movement; and establishment. Instability is characterized by environmental and/or social instability that causes displacement. Movement is the act of displacement, and the change of residence from the place of origin to a new place. Establishment is when interactions occur that link immigrants among themselves, facilitating their stay at the destination and making it lasting or permanent.

Our model integrates elements from both models to analyze the migration process as part of an IE field in which IE attributes can be identified as differentially expressed in HK, SK, and CK. It includes four stages:

- (1)

Instability. The need or desire to emigrate arises in response to imbalances or problems. Although the possibility of emigrating exists, action may not yet be the objective.

- (2)

Preparation. The resources needed to move to a different place are obtained.

- (3)

Action. Movement occurs; emigrants leave the point of origin to arrive in other social, economic, cultural and political environments.

- (4)

Establishment. The immigrant accumulates enough resources to live in the new sociocultural context. This is a period of adjustment during which transferable resources are modified and new capitals are acquired; it is not always successful (Lomnitz, 1975). Situations can arise in the new context that can generate new instabilities and drive new movement in search of other options.

Education, and mainly IE, is a permanent process (Richmond, 1975). Immigration forms part of education because migrants can acquire new knowledge, abilities, attitudes and values that are closely linked to CK, HK, and SK. To focus our study on education we used four concepts, or attributes (Argudín, 2005):

- -

Knowledge: the information obtained through use of intellectual faculties, experience and relationships within the context.

- -

Ability: the aptitudes or physical and/or intellectual skills used to execute an action.

- -

Attitude: a quality of personality encompassing thoughts and feelings and how they are reflected in actions. Attitudes form part of the constant construction of an individual.

- -

Values: an abstract principle reflected in the ability to make decisions via critical thinking related to ethical beliefs. Expression of values can be observed in certain contexts through the practice of abilities, knowledge application and, generally, in individuals’ attitudes.

Education does not refer to a particular process but rather to a wide range of processes in which a person can learn from others and appropriate knowledge, allowing social and personal fulfillment (Peters, 1967). For Richmond (1975), education is a process in which individuals learn through socialization and resocialization, and which trains them to meet their needs and transform their medium. For it to transform the world, Freire (1970) states that education, which involves praxis, reflection and individual action, must promote a change in attitude that substitutes passive habits with participation and intervention. From Freire's (1970) point of view, education is an act of bravery in which the individual ceases to be the receiver of political and social decisions and begins to act in the interests of his/her own self-construction. Real education occurs through mediation with the world and in relation with one's own society (Freire, 1974), beginning with the fact that humans are rooted in temporal and spatial conditions that mark them and which they in turn mark. Education should cause the individual to reflect on her/his situation and to act to change it. In this sense, immigration can be an education process.

Informal education is a spontaneous process in which learning occurs through conversation, exploration and experience, one in which human growth involves communities, associations and relationships (Jeffs & Smith, 2011). During immigration, one acquires education expressed in terms of HK, CK and SK (Monkman, 1999; Yildiz, 2010). This is why we linked the attributes of knowledge, abilities, attitudes and values to each type of capital. We also utilized the theoretical approaches of Bourdieu to analyze the relationships between these capitals.

CapitalsIntegration of the HK, SK and CK used during migration enriches immigrant experiences, making them the principal agents in building their education.

Human capitalHuman capital (HK) has been conceived as a set of abilities representing an asset that enriches people's lives (Lanzi, 2007) and includes (a) basic abilities such as reading and writing; (b) professional competences such as product manufacturing techniques or tool use; and (c) the use of complex functions implying self-learning processes and problem solving. It can be used and/or augmented during immigration, thus producing a more efficient migration process (Schultz, 1975). Part of the HK concept has been linked to education level and its expression in the work and economic spheres (Bourdieu, 1986; Coleman, 1988). A number of researchers have analyzed the implications of HK together with CK to help understand immigrant experiences (Chiswick, 2000; Erel, 2010; Hirabayashi, 1993; Massey et al., 1998).

Cultural capitalIn his conception of CK, Bourdieu (1986) highlights the importance of culture, knowledge transmission and incorporation, and cultural practices in − and outside formal education. Cultural capital (CK) can exist in three states: embodied, objectified and institutionalized. Embodied CK includes resources acquired through investment of individual time and effort. Objectified CK is the physical, potentially transferable goods one possesses. Their value is linked to embodied CK and its meaning for a certain social group. Institutionalized CK refers to formal recognition such as academic degrees.

Social capitalSocial capital (SK) is a resource that can be transformed into HK, CK and economic capital (Bourdieu, 1986; Coleman, 1988; Portes, 1998). It is “the sum of all real and potential resources linked to possession of a lasting network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual recognition” (Bourdieu, 1986: 248). This aspect of social structures facilitates certain actions for its agents (Coleman, 1988: S98). Social capital (SK) refers to values, norms and networks within a social organization in which cooperation is expressed through mutual trust (Putnam, 1993). A social network (SN) is a type of SK consisting of personal relationships in different ambits. Because SNs are represented by groups of people that implement processes reflected in personal and collective life, they can be viewed as structures that generate either positive or negative effects (Navarro, 2004).

We considered SK as consisting of resources derived from establishment of social relationships in which individuals acquire and share values and knowledge, among other resources, that allow them to act in a coordinated manner and attain a goal. We tied values to SK since it can focus the behavior of immigrants toward certain SNs as they search for support. Social networks are also spaces for exchange of knowledge, abilities and experience, which allow and promote the search for conditions that offer social support and thus contribute to overcoming crises (Navarro, 2004).

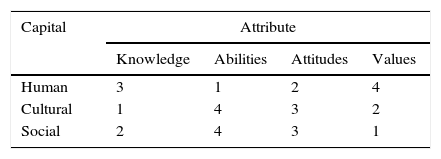

Attributes of education and capitalsIn a literature review, we identified relationships between each attribute of education and the analyzed capitals, and found that knowledge, abilities, attitudes and values can be incorporated and expressed in individual behavior. Therefore, these education attributes can be clearly expressed in each capital. In the literature, education attributes are described as being expressed differently in each capital (Table 1).

Gradient of expression of education attributes by type of capital.

| Capital | Attribute | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | Abilities | Attitudes | Values | |

| Human | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Cultural | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Social | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

1: Major; 2: Medium; 3: Basic; 4: Minor.

Bourdieu (1986), Coleman (1988), Erel (2010), Hirabayashi (1993), Lanzi (2007), Monkman (1999), Portes (1998), Richmond (1980), Schultz (1975), and Yildiz (2010).

Using a gradient of Major (1) to Minor (4), we ranked attribute expression in each of the three capitals addressed here; all four attributes are necessary for a capital to manifest itself. For HK, we graded the attributes based on Lanzi (2007), who refers mainly to development of abilities (1) reflected in each individual's attitudes (2). HK also depends on CK to the degree that it is linked to the use of knowledge (3) acquired in the family, school and community (Bourdieu, 1986), which is where values (4) are exhibited (Argudín, 2005).

CK is mainly based on the transmission and incorporation of knowledge (1) and values (2) (Bourdieu, 1986). In cultural practices, we found that attitudes (3) and abilities are expressed in a minor way (4) because their transference depends on an individual's skills and the time spent perfecting them.

Values (1) are the most obvious attribute of SK. Putnam (1993) linked this capital to the values, norms and networks of a social organization. Social networks (SNs) are places where knowledge (2) is shared, acquired and transmitted, and then expressed through attitudes (3). Abilities (4) can be manifest through actions but these may or may not be present in networks, depending on the situations requiring social support.

Using the literature review and our model, we designed the instruments for collecting data on the relationships between each education attribute and the SK, CK and HK employed by the studied women in their migration processes.

MethodWe interviewed nine women (32–75 years of age) who emigrated from rural areas in Yucatan, Mexico, to the state capital, Merida. Using an ethnographic approach and direct interaction implemented by a team member (ASP) from October to December 2011, we built a conjoint results analysis (Creswell, 1998; Mayan, 2001). To understand the migration process from these women's perspectives, we used techniques such as participatory observation, and semi-structured and in-depth interviews (Yin, 2003).

A case study was used to collect in-depth data on their context (Creswell, 1998), which broadened our understanding of the way, and under what conditions, the participants experienced and interpreted their migration process. All participating women had lived at least 10 consecutive years in Merida, a period we chose assuming that it would be sufficient to identify the knowledge, abilities, attitudes and values they had acquired during the Establishment stage. Participants were located by first surveying the area, then a “portera”1 (gate-keeper) was identified and the “snowball” technique applied (Polsky, cited in Taylor & Bogdan, 1998).

To collect data, we interviewed participants about the IE they acquired before, during and after they immigrated to Merida. Before interviews were conducted, participants provided verbal consent to participation in the study, and authorized recording of the interviews. The interview guide included 91 questions divided into four sections, allowing identification of the capitals available to the women in each of the migration process stages.

We inquired about the HK, CK and SK acquired in each migration stage. In the Instability stage we identified the attributes they used during the last year living in their point of origin. For Preparation we focused on the resources they accumulated in anticipation of moving to a different place. Data for Action included the resources used for and during movement. Finally, for Establishment we identified the attributes they used, modified and acquired during their first ten consecutive years living in Merida.

ResultsOf the four stages of the migration process − Instability, Preparation, Action and Establishment − the second and third were the least complex and temporally shortest. The participants took from five hours to two months to prepare to move and the actual moving took from 45min to 4h, and involved distances of 30–400km. In response, the study focused more on the Instability and Establishment stages. Analysis of the Preparation and Action stages would probably be more informative in situations involving much longer distances and time periods. The Instability and Establishment stages were much longer and more complex for the study participants, allowing a more complete analysis of IE.

When they emigrated, five of the participants had jobs, seven emigrated with a member of their nuclear family,2 and two did so alone. All came from rural locations with populations, at the time they emigrated, of 2500 or fewer inhabitants. Age at time of departure ranged from 15 to 42 years old, and they established themselves in Merida at ages ranging from 17 to 42 years old. When interviewed, participant age ranged from 32 to 75 years. Four of the women had been living continuously in Merida for 10–20 years, two had been there for 21–30 years and three had been there for 31 years or more. In terms of marital status, one lived with her partner, another was a widow and seven were married, although two had separated from their husbands.

As we interacted with the participants, we reconstructed their migration processes.3 This exercise allowed us to develop a group description of the process, independent of place of origin, type of movement, and job and family situation at the time of emigration.

InstabilityRanking of the education attributes as expressed in HK in this stage was abilities (1), attitudes (2), knowledge (3) and values (4) (Table 1). During this stage, we mainly identified the abilities used to carry out daily activities such as communication (mainly verbal), problem solving, critical thinking, analysis, decision making, social relations (e.g. values, culture), functioning (e.g. administration, planning, resources use), leadership (e.g. collaboration, creativity, planning) and knowledge integration. When still in their places of origin, all participants took part in planting and harvesting corn, preparing handmade tortillas, cutting fuel wood, and raising animals for daily use and during special events such as family and community celebrations. Five were involved in marketing part of the harvest and had become skillful at sales, thus generating income for their families. My dad planted chilies, radishes, all that… jicama, they brought it in and I would go out and sell (it) in the streets in town.4 Yup, I’d go out and sell, ten minutes later I’m back because I sell it all fast because well we need to eat and everything (Rode,5 68 years old, 51 years in Merida).

Seven of the participants knew how to weave hammocks, sew and cross-stitch dresses or decorations, abilities developed through learning from a relative before emigrating.

Within CK, the education attributes were ranked as knowledge (1), values (2), attitudes (3) and abilities (4). To identify knowledge within CK we distinguished between embodied, objectified and institutionalized CK.

Only one participant had studied a technical degree (institutionalized CK) during the Instability stage, although she did not finish because her husband did not allow her to continue: “It was like a degree. It was technical…something to do with computing… I do not remember how long it was, but there were only like two months, I think, until I finished (…) but that x’lá6 man did not let me” (Eve, 38 years old, 11 years in Merida).

Of the remaining eight participants, one reported not having gone to school, five had studied some portion of elementary school, one had studied a portion of middle school and one had finished middle school. The reasons for not going to, or not finishing, school included lack of school facilities or the necessary grades in the place of origin, dislike of school or family reasons.

Objectified CK is related to HK, and acquired knowledge can be complemented by an individual ability; for instance, objectified CK can be observed in handcrafts production. Seven participants said they had learned to make dresses, decorative products and hammocks from their mothers, other female family members or neighbors. Only three used these abilities to generate income in the year before emigrating. They taught me… my grandmother in my first year (living with her) there (in her house), I was learning at seventeen (years of age) to knit, to weave, to sew, everything … and in one year I learned all that. I’m7 learning to weave, they’re teaching me to weave and I’m taking advantage to deliver hammocks, for profit, well, what they pay me is my profit (Abigail, 54 years old, 36 years in Merida).

In terms of embodied CK, eight participants said they used knowledge about working in agricultural fields. First clear the bush, measure it, square it and then clear it, then they burn it, later … after the first rain falls they plant, once the corn sprouts they start to weed inside the field. Sometimes if they want to plant cucumber, squash or watermelon they plant them under (the corn plants). (We) had everything… corn, watermelon, cucumber, melons…beans, fava beans, cowpea, squash, xtóop’ito8 that they eat with flowers… (Beatriz, 51 years old, 25 years in Merida).

For example, the process some followed in their hometowns involved harvesting in the field, cutting fuel wood and cooking the food: “There you went to harvest corn, squash…to look for fuel wood and everything…you have to go soak your corn, grind it, shape it. One does that in town (Raquel, 75 years old, 41 years in Merida)”. Participants mentioned that they had acquired this knowledge through observation or direct participation with a member of the nuclear or extended family. The learning process had begun when they were children and continued until they had their own families.

All participants said they knew how to do domestic work such as food preparation and clothes washing. For instance, some grains, like corn, required cooking as well as grinding for tortillas, tamales, atoles and other dishes. For washing clothes, the water was treated beforehand by mixing in ash. Only then was powdered detergent or bar soap used to wash the clothes: “There (in town) instead of using bleach they took ash, put it in a dish and then in the water and the next day it's good for washing (Beatriz, 51 years old, 25 years in Merida)”. Although they had acquired this knowledge at an early age, only three participants had used it in the year before emigrating.

Three participants said they had learned how to treat diseases from other women in their families, such as a grandmother or aunt: … My deceased grandmother taught me. She told us what to do when one is sick, you have no money, you can’t go to the doctor, if your children are dying. Yah…from when I was young, because she looked for things for us…she gave us remedies when we were vomiting, when we had acesido9 for example she would take care of us. When I was older, when my mom had died is when she taught me, and my aunts taught me…my dad also knows about herbs, they taught us to look for herbs (Rode, 68 years old, 51 years in Merida).

Only one participant said she had taken part in educational activities such as government programs teaching cooking, handcrafts and health. The remaining eight had not participated in courses or workshops because they were not available in their place of origin, “they did not have time”, or their family did not allow them to go.

We linked the participants’ belief system-related knowledge to values acquired in their communities, and more specifically in their families; all said they had participated in religious activities at least once a week. Their participation in family and religious activities was important to identifying where they had acquired their belief system, an aspect of the IE process. Their beliefs were related to the treatment they received and gave in their families, as well as moral aspects that controlled their behavior. Two explained the treatment they received from their husbands: “That's the education they gave me, it was to obey your husband and, like I said, if he said it's black well it's black” (Abigail, 54 years old, 36 years in Merida).

They also commented on their treatment in the family and community: There (in the town) …if (a person) is older than you, you cannot say anything even though you’re right (Beatriz, 51 years old, 25 years in Merida). They made us believe that the woman had no right to study; the men did because they supported (the family). The woman did not support it, even their (her children's) father said so, “[if] my daughter studies, who am I helping? her husband” (Raquel, 75 years old, 41 years in Merida).

The participants said that in their towns they had been taught one or more of the following aspects: (a) obey your husband; (b) not to go out at night to avoid negative comments about their reputation; (c) formal education priority given to men because they would become heads of household; and (d) not to contradict older people, including family members and acquaintances. Disobeying these norms had consequences. Three participants said they had been insulted or hit by their husbands for disobeying an order. Another three said that after spending a night away from home with their boyfriend their families no longer allowed them to live with them, and they had to live with their partner's family. The emphasis on schooling men may be responsible for the participants’ generally low education level. Finally, three said they had been insulted or hit by a family member for contradicting someone older than them.

Within SK, the four education attributes were ranked as values (1), knowledge (2), attitudes (3) and abilities (4) (Table 1). We identified the principal SNs available to the participants, mainly during the Instability and Establishment stages when support and collaboration were most evident. Their comments on the final year they spent in their points of origin showed that their strongest SN consisted of members of their nuclear families followed by members of the extended family (e.g. grandparents, uncles/aunts, brothers/sisters-in-laws, and fathers/mothers-in-laws). These SNs were based on collaboration and distribution of activities such as housework, field work or problem solving. Two participants had received assistance from these people to find work in their point of origin. They also had SNs based on friendships which they had developed while participating in community religious or cultural activities. All nine had experienced social contexts outside their community through outside friendships. The comments of six participants helped in identifying these two SNs in the work ambit. Family or friends offered them economic resources to acquire personal articles, study or help their families with money or goods. “A girlfriend told me ‘I found you work’. Because I told her…because she came here to Merida to work, because I know she travels a lot here in Merida, so I told her (that I was looking for work)” (Loida, 55 years old, 20 years in Merida).

EstablishmentDuring this stage, the ranking of the four attributes in HK was abilities (1), attitudes (2), knowledge (3) and values (4) (Table 1). Seven participants continued using the fieldwork abilities they had learned to plant and harvest in their yards in the city, despite limited space and smaller harvests. All nine participants learned new methods of domestic labor, be it in their own homes or as domestic workers. During their first years in Merida, eight cooked using a gas stove and only one still used wood for cooking. For their first ten years in Merida, all lived in houses with electricity, piped water, a washing machine and a full bathroom built of permanent materials. It was a different way of working in the town. It is very different (there); you go to the fields, harvest, you have to look for fuel wood, soak your corn and mill it…In contrast here well…there's none of that. Here, well…they even bring tortillas (to the house) (Noemi, 32 years old, 11 years in Merida).

The ability to save a portion of family income was developed individually, but once in the city five participants had used formal or informal institutions to save money and acquire credit. Three had participated in mutual benefit societies (mutualistas), which are informal savings-credit groups generally organized among neighbors. Each group member contributes a previously agreed amount, normally every month. Once the month's collection is complete, a member is paid the full collection, following a predetermined order. These same participants had also saved in formal financial institutions, and then used these savings as collateral to solicit a loan. Their reasons for saving were various. Eight said they did it to build their house or part of it; two did it to invest in a business and another two as back-up for family emergencies. Some of the participants provided more than one answer to this question.

All said the main need they confronted in Merida was that of money to cover transport, buy food and pay school expenses. What's difficult here is that if you don’t have money you can’t even take a bus. So you look for work and in two days here's your money (Vashti, 38 years old, 10 years in Merida).

All participants said that in addition to developing the abilities needed to acquire money, they learned to relate to people in a different way. “Here I learned more…the way to communicate with the person, to know the person like he is, how to treat people. In contrast in the town… the customs are different” (Abigail, 54 years old, 36 years in Merida).

For CK, the four attributes were ranked as knowledge (1), values (2), attitudes (3) and abilities (4) (Table 1). Once in Merida, only one of the participants developed institutionalized CK during the first 10 years. She joined an adult education system and finished elementary and middle school. Four participants took part in courses and workshops addressing human values, cooking and handcrafts; these were organized by religious groups or the city government. Here…first we learned to value ourselves more. In the town it's like you’re oppressed…by machismo, then this…getting out and taking the classes I took helped me…There, for example, when you say “I want to go and learn this thing” they tell you “if you haven’t learned when young less so when you’re old, an old person is stupid…” they tell you (Beatriz, 51 years old, 25 years in Merida).

Objectified CK during Establishment was identified in three participants who made dresses, decorative products and hammocks, and continued to do so after immigrating. They had embodied new knowledge from those who had asked for their products or from courses and workshops. None of the participants said they had done agricultural work in the city, but four said that shortly after arriving in Merida the knowledge they had acquired in their points of origin was useful in planting and harvesting backyard gardens. This embodied CK had helped them during the Establishment stage. Well here I cook with a stove, I have a fridge…I have my house which is mine, I say it's mine. There (at her town) I got up early and I had to fill up the water because there's not water all day like here. There was a time you had to fill your buckets. You get up late and you do not get the water (Vashti, 38 years old, 10 years in Merida).

As occurred in the Instability stage (Table 1), all nine participants considered the family to be the strongest SN in the Establishment stage. Six had formed their own families with their husband and children. During their first years in Merida, their nuclear family (parents and siblings) had remained in the place of origin and so their main local support was their husband and children. For three participants, the support of a family member in the city was key for their having stayed since it provided them with housing and they were able to share food and childcare expenses.

Friendships were another important SN during their first ten years in Merida. Six participants stated that relationships with neighbors and members of religious groups also helped them during the Establishment stage. Thank God, I’ve had no needs, they’ve helped me a lot (…) my neighbors. That's why, when my son got sick, (they) even gave me jewelry to pawn so I could pay to treat my children (…) (at) work when my patrona (boss) said “you want money?, here you go, pay your debts”, they really have helped me, my patronas and all that yeah, they really have helped me (Rode, 68 years old, 51 years in Merida).

In contrast to the Instability stage, some participants stated that once in Merida work networks were not important for them. Only four worked as domestic servants when they arrived, and only two received support from their patronas for housing, loans for emergencies and recommendations for another job.

During Establishment, five participants built new SNs though participation in government programs for acquiring and building housing and receiving food assistance. Non-governmental organization (NGO) programs were another network used by participants. Two had used them for support to acquire building materials for their houses, school supplies for their children and monthly food assistance for their families. Three had participated in human rights training programs and three others in cooking and handcrafts workshops.

In terms of knowledge acquired via IE, six participants stated that they had perceived and acquired other ways of treating people and being treated by them. Those that had been hit or insulted by family members in their point of origin began to demand better treatment. Others changed the way they evaluated themselves: “Here it's like they wake you up to another way of thinking. Now, you can for example, learn lots of things and not feel that you cannot (Beatriz, 51 years old, 25 years in Merida)”. “I learned here in Merida…to improve myself in many ways (…) in the moral aspect, economic and to learn things (Abigail, 54 years old, 36 years in Merida)”.

Two participants mentioned they had acquired knowledge about family planning through friends and applied it. They later decided which method to use, seeking advice from health professionals. After the birth of her fourth child, one participant decided to use a permanent birth control method. Another had used birth control during two periods in her life. One participant reinforced her reading and writing skills through a television program, and another was taught to read and write by her children.

DiscussionThe migration process caused changes in the participating women, who observed that they had modified their roles in the home and their social relationships. Ariza (2007) and Szasz (1999) documented differences in power relationships through migration that went beyond the domestic ambit. Hondagneu-Sotelo (2007) states that migration alters women's social relationships as they enter the employment ambit and SNs. Our results show that these relationships affect women both inside and outside the home.

Although no results were presented from the Preparation and Action stages, data from the Establishment stage agreed with Du Toit (1990), suggesting that the participants prepared their migration in premeditated, planned acts as part of a process.

Unlike the model proposed by Tabor and Milfont (2011), the first and fourth stages in the present study manifested similarities. In the Instability stage, personal factors could be identified that motivated the migration, but the most consistent finding was that the women perceived that they had strong support from their SNs to migrate. Establishment saw the participants making personal adjustments and sociocultural adaptations that influenced their decision making, while their cultural identity was exposed as they interacted with their new surroundings in the city.

Incorporating elements of Lomnitz's (1975) ecological model allowed identification of the changes experienced and adjustments made by the women as they emigrated from a rural to an urban zone, exposing themselves to a different environmental and cultural context. However, the lack of substantial data for the Preparation and Action stages (distances and times were quite short) prevented comparison of our model with that of Lomnitz. If more detailed information on these two stages can be gathered in future research, perhaps it will allow analysis of the capitals that helped migrants in these stages.

Analysis of the participants’ migratory process experiences confirmed that for them the education process is permanent, as observed by Richmond (1975) and Peters (1967). Elements of education discussed by Freire (1970, 1974) that were identified in their processes included reflection, practice and intervention. The participants implemented these through mediation with the world. They acquired new knowledge, abilities, attitudes and values: the four education attributes distinguished by Argudín (2005).

The women in Merida studied here exhibited patterns similar to those reported by Monkman (1999) in a study done in California. They used acquisition of capitals through their migration experience to build a new, different life in their destination. Methodologically linking these capitals with education attributes allowed as to identify the migration process as an IE ambit, in keeping with Monkman (1999) and Yildiz (2010).

All the participants in our study already possessed abilities, which they applied in their new environment. They also acquired and applied other abilities as part of the migration process, and, in conjunction with their existing abilities, these constituted part of their HK (Bourdieu, 1986; Coleman, 1988; Lanzi, 2007). In addition, they identified SK values in the form of SNs, and CK in the form of knowledge acquired during the migration process (Bourdieu, 1986). When related to education attributes, these three kinds of capital enriched their lives before, during and after their immigration to Merida.

ConclusionsBased on the gradient of expression (Table 1), we identified the elements that linked each education attribute to each type of capital. Knowledge was linked to CK because it refers to knowledge transmission and cultural practices. Participant aptitudes and skills were linked to HK. Values, the principles that orient human behavior, were linked with SNs (a specific type of SK), in which group cooperation is expressed, and knowledge and other resources are exchanged via support networks. Also, as the women expanded their SNs, their SK and values experienced changes that impacted their HK. We related attitudes to all the studied capitals because they reflect an individual's construction of knowledge, abilities and values.

Based on the present results, the participating women's principal actions implied using these three capitals to change their lives; using the concept of the capitals helped us to identify part of the education they acquired during their immigration processes. Changes in HK occurred in aspects of domestic work, access to formal financial institutions, adjustment of income to a new environment, and the way they related to others in the city. The women augmented their preexisting CK (which consisted largely of agricultural skills) by taking courses and workshops on human values, cooking and handcrafts. In terms of their SK, the participants acknowledged that the strongest SN continued to be their family, but during Establishment friendship and religious SNs provided them with moral, economic and social support. Additional SNs arose as they participated in non-profit organization and government programs aimed at assisting them in purchasing or building their homes, or accessing health care. By utilizing theoretical and methodological components, we were able to identify the relationships between the education attributes and the three capitals. The women's experiences helped us to distinguish the resources they had used and transformed in their individual immigration processes.

In the IE they incorporated during their immigration, the women acknowledged having experienced changes in the form of housework, handcrafts, interpersonal relationships and demands for better treatment from those around them. All these changes are closely linked to the gender relationships they experienced in their points of origin in the Instability stage, which were transformed during their migration process. We observed that the four education attributes studied here were present in the women's immigration processes, meaning migration can therefore be considered a field of IE.

Author's noteThe research reported here was financed by the National Council for Science and Technology (Conacyt), which also provided a Masters in Science scholarship (#302915) and a scholarship (#290618) for an academic stay at Ohio State University. Authors contributed in the following way to this paper: ASP, MTCB and FD: data analysis and writing of the first draft and APC: final report.

We thank two anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions and criticisms.

These are women connected to different social agents, contexts and situations. In the present case, they were a vital link between researchers and agents (Hammersley and Atkinson, 2007:52).

Peer review under the responsibility of Asociación Mexicana de Comportamiento y Salud.

Parents, siblings and children (Barfield, 1997).

Possible bias in participant memory and interpretation of the past has been considered. Camarena Ocampo, Morales Lersch, and Necoechea Gracia et al. (1994), Hammersley and Atkinson (2007), Mayan (2001), Bricker (1989) and Taylor and Bogdan (1998) agree that the technique used in the present study is as valid as other information sources because the agents themselves narrate their perspective of events. Betty Faust provided key orientation in this area. It is also important not to forget, as Eco (1994) clarifies, that every text has infinite possible interpretations.

The interviewees’ references to “town” (pueblo) refer to their places of origin.

All text quotations are from the field notes. Names have been changed to protect participant identity.

No clear translation exists for the concept underlying the Maya word x’lá. It can express disgust, loathing, hatred, ridicule, derision and/or jest in formal and informal contexts.