En este trabajo se investiga si hay diferencias sistemáticas entre los bancos convencionales y los bancos participativos en cuanto a su respuesta a las sacudidas en política monetaria. Para tal efecto, se ha observado el crecimiento trimestral de los préstamos de los bancos comerciales y participativos del sector bancario turco para ver si el flujo crediticio de la política monetaria difiere según el tipo de banco. Al mismo tiempo, se ha controlado por algunas variables específicas de cada banco, como el registro de activos reales, la proporción de activos líquidos respecto al total de activos y la proporción de acciones sobre el total de los activos. Se ha encontrado que los bancos participativos muestran reacciones más amplias a la política monetaria. En cuanto a las variables bancarias específicas, los bancos con tasas de liquidez mayores tienden a presentar mayor crecimiento crediticio, mientras que los bancos con activos de mayor tamaño tienen crecimientos crediticios menores.

In this paper I investigate whether there is a systematic difference between conventional banks and participation banks in terms of their response to monetary policy shocks. For this purpose I look at the quarterly loan growth of commercial banks and participation banks in Turkish banking sector and see whether the lending channel of monetary policy differs depending on bank type. At the same time, I control for some bank specific variables, namely the log of real assets, the ratio of liquid assets to total assets and the ratio of equity to total assets. I find that participation banks show larger reaction to monetary policy. In terms of bank specific variables, banks with higher liquidity ratio tend to have higher loan growth, whereas banks with larger asset size have smaller loan growth.

1. Introduction

The lending channel of monetary policy has been a topic of research for many economists and policymakers. The general wisdom is that when the central bank adopts a monetary policy tightening by raising the interest rates, this leads to a rise in the funding costs of banks and therefore a reduction in loan growth. The studies reveal that lending channel of monetary policy works for many economies but the reaction of banks to changes in monetary policy is not uniform and depends on various factors. In this regard bank fundamentals have a significant impact on the lending channel of monetary policy. Peek and Rosengren (1995) found that bank capitalization, measured by the ratio of capital to total assets, affects the reaction of banks to monetary policy. Kishan and Opiela (2000) investigated lending channel of monetary policy for U.S. banks from 1980 to 1995 and they found that small banks and undercapitalized banks were more affected by monetary policy. In another paper Kishan and Opiela (2006) analyze the lending channel of monetary policy for low-capital and high-capital banks during expansionary and contractionary monetary policy periods. They found that banks that are well-capitalized are less affected from contractionary monetary policy. Kashyap and Stein (2000) also analyzed the monetary transmission mechanism for U.S. banks and found that the lending channel of monetary policy has larger impact on banks with lower ratios of cash and securities to assets. Stein (1998) also found that banks that have lower ratio of liquid assets to total assets tend to show larger reaction to contractionary monetary policy.

The studies also reveal that bank ownership and the level of competition in the market also affect the lending channel of monetary policy. Macit (2012) studied the Turkish banking sector from 2006 to 2010 and investigated whether the ownership structure of banks affects their response to monetary policy. He finds that public banks show the smallest reaction to monetary policy, whereas foreign banks are the most responsive banks.1 Bhaumik et al. (2011) analyzed the implications of bank ownership for lending channel of monetary policy for Indian banking sector. They found that bank ownership has significant impact on the reactions of banks to monetary policy. Olivero et al. (2011) investigated the impact of the level of competition in banking sector on the lending channel of monetary policy by looking at the data for commercial banks in 10 Asian and 10 Latin American countries from 1996 to 2006. They found that the lending channel of monetary policy is weakened as the level of competition increases.

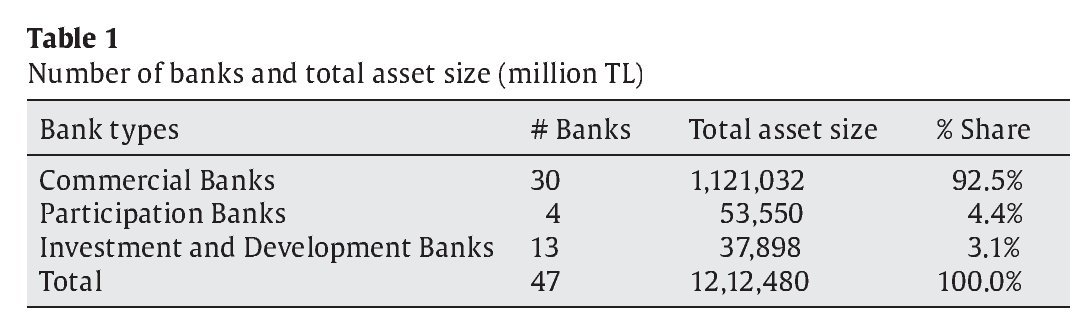

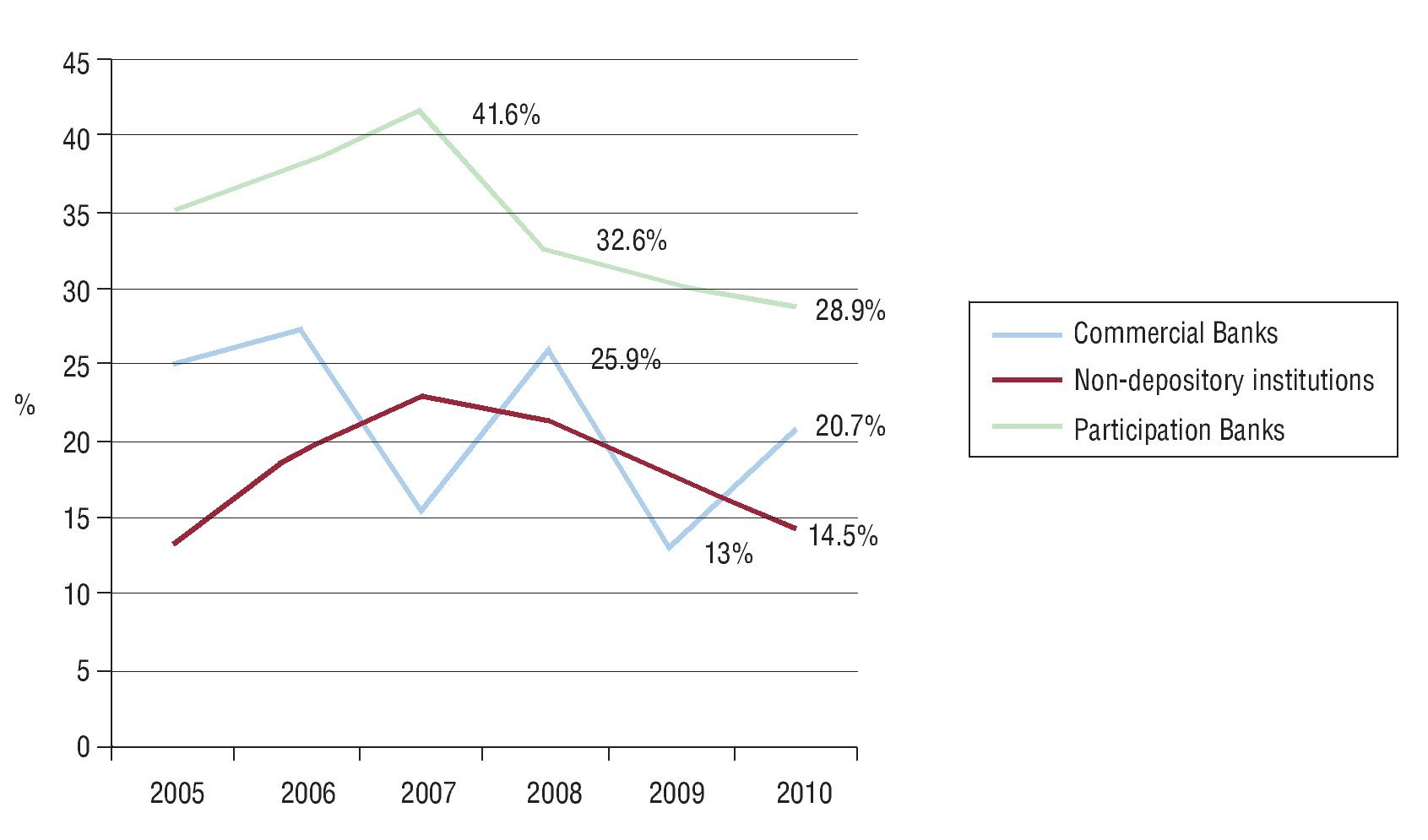

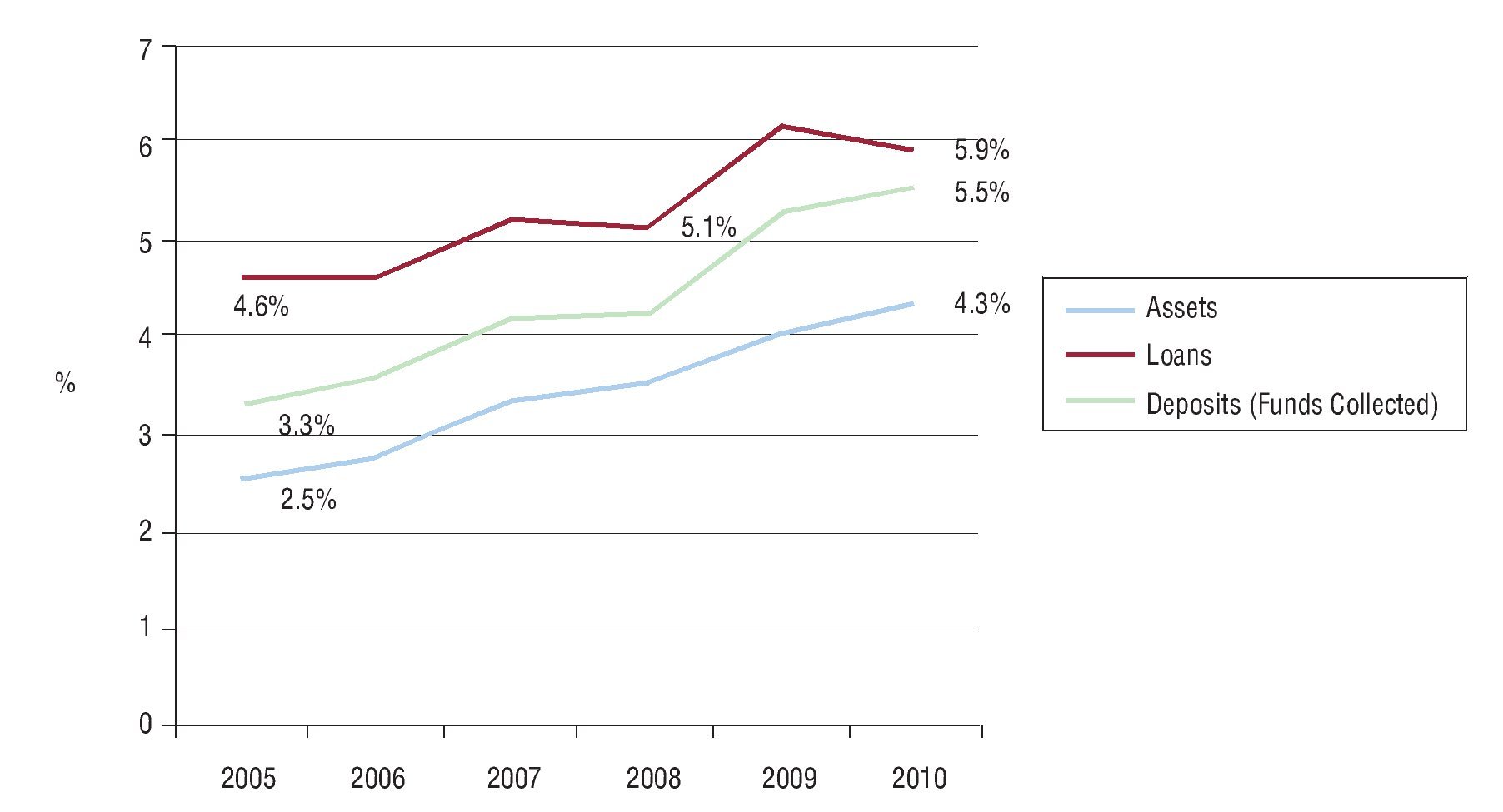

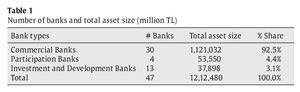

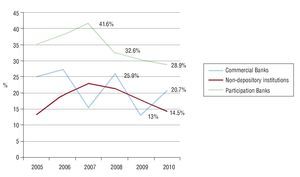

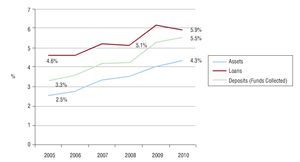

The contribution of this paper to existing literature is that it investigates the lending channel of monetary policy for the Turkish banking sector and analyzes whether banks' reactions to monetary policy change depending on their type. In particular, I probed whether there is a systematic difference in the response of commercial banks and participation banks to changes in monetary policy. In the Turkish banking sector there are three types of banks, namely commercial banks, participation banks, and investment and development banks.2 Table 1 shows the number of banks and total asset size for each type by the end of the third quarter of 2011. In the Turkish banking sector, commercial banks significantly dominate the sector and they hold about 92.5% of the total assets in the Turkish banking sector. Participation banks operate according to Islamic rules in their lending and deposit collection activities, and they own about 4.4% of total assets in the sector. As opposed to commercial banks, they do not promise a fixed interest payment to their depositors. Instead, the funds that are collected from depositors are utilized in trade and industry, and the profit that is obtained from the lending pool is shared by the depositors. The name "participation banks" also stems from the fact that the depositors participate in profit or loss that results from the activities of the bank. As can be seen in Figure 1 and Figure 2, even though these banks occupy a small place in the sector, their rapid growth rate implies an important future potential for them.

Figure 1. The growth rate of assets for different bank types.

Figure 2. Share of participation of banks in terms of assets, loans, and deposits.

In order to investigate whether there is a difference in the reactions of commercial banks and participation banks to changes in monetary policy, I looked at the quarterly loan growth of these banks to see how it is affected from a change in monetary policy instrument. At the same time, I verified for some bank specific variables, namely the log of real assets, the ratio of equity to total assets, and the ratio of liquid assets to total assets. I found that participation banks were more responsive compared to commercial banks in terms of lending channel of monetary policy. The results also reveal that in general, banks that have higher ratios of liquid assets to total assets tend to have higher loan growth whereas banks with larger asset size are more likely to have lower loan growth.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 gives a description of the data and empirical model. Section 3 presents the estimation results and policy implications. Section 4 concludes.

2. Data and empirica l model

2.1. Data

The data th at is used in the paper is a quarterly data that cover the period from 2006 to 2010.3 The data for commercial banks which include quarterly loan growth, the log of real assets, the ratio of liquid assets to total assets, and the ratio of equity to total assets is calculated from unconsolidated balance sheets of banks obtained from the Banks Association of Turkey database. Participation Banks Association of Turkey database is the data source for participation banks.

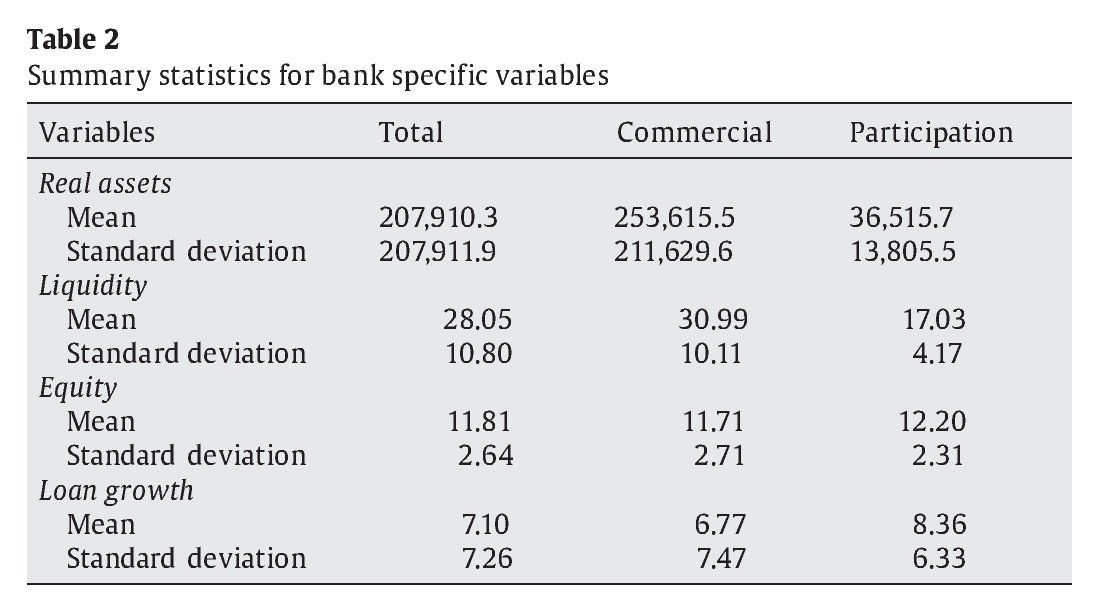

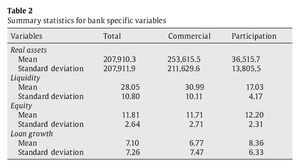

Table 2 gives a brief summary of bank specific variables used in the model. The results reveal that in general commercial banks are much more liquid than participation banks measured by the ratio of liquid assets to total assets. This is in fact related to the nature of participation banks. These banks, as they operate according to Islamic rules, are not allowed to hold interest-bearing securities. Therefore, their alternatives in terms of investing in liquid assets are very limited and they keep a very large portion of their assets in the form of loans.

There is not a big difference between commercial banks and participation banks in terms of their capitalization. Both types of banks are well-capitalized. In terms of loan growth, participation banks have higher quarterly loan growth on average. This is actually consistent with the purpose of these banks as they channel a very large portion of the funds they collect for lending.

In terms of the choice of monetary policy instrument, the literature generally uses the target interbank rate by the central bank as the monetary policy instrument. For instance, in the U.S. case, Kashyap and Stein (1995) use the federal funds rate as the monetary policy instrument. Gambacorta (2005) uses the refinancing rate of European Central Bank for a study related to the European banking sector. In this paper, I use the overnight lending rate by the Central Bank of Turkey as the monetary policy instrument. The reason is that this rate significantly affects the interbank rate and, therefore, influencing the funding costs of banks has an impact on loan supply of banks.

2.2. Empirical model

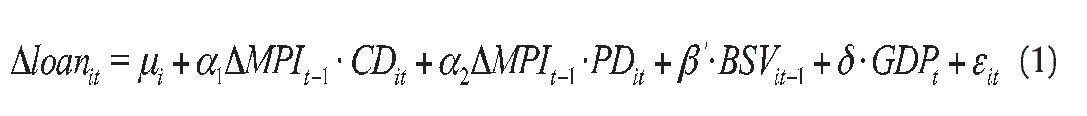

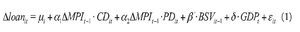

The reduced form equation that is estimated using fixed effects estimation can be written as follows:

where Δloanit represents the quarterly loan growth of bank i at time t and ΔMPIt-1 refers to the change in monetary policy instrument at time t. The monetary policy instrument is put in the model with a lag as any change in monetary policy will be more likely to affect the loan growth of banks only in the next quarter. CD and PD are dummy variables representing commercial banks and participation banks respectively. BSVit-1 is a vector of bank specific variables for bank i at time t - 1. It includes the log of real assets (LRAit - 1), the ratio of liquid assets to total assets (LIQit - 1), and the ratio of equity to total assets (ETAit - 1). Again, following Bhaumik et al. (2011), bank specific variables are put in the model with a lag. The growth rate of GDP is included as a macroeconomic control variable and μi stands for unobservable bank specific fixed effects.

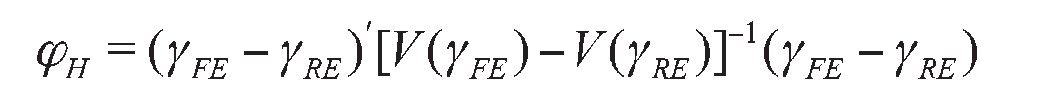

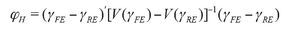

The model is estimated using fixed effects estimation method. The other commonly used estimation technique for panel data models is random effects estimation. The difference between the two estimation techniques is that fixed effects estimation treats the bank specific unobservable effects μi as fixed, whereas the random effects model treats them as random. However, in order to be able to obtain consistent estimators in random effects estimation, one should assume that μi¿s and the other independent variables in the model are not dependent. Hausman (1978) provides a test statistics in order to test whether μi¿s and other explanatory variables are independent. Hausman test statistics is given by the following equation:

The Hausman test statistics has a chi-square distribution under the null hypothesis with degrees of freedom equal to the number of regressors. The results reveal that they are not independent and fixed effects estimators should be preferred to random effects estimators in order to obtain consistent estimators. The value of the test statistics is obtained as 54.75, which leads to the rejection of the null hypothesis. This implies that fixed effects estimation should be preferred to random effects estimation.

3. Estimation results and policy implic ations

3.1. Estimation results

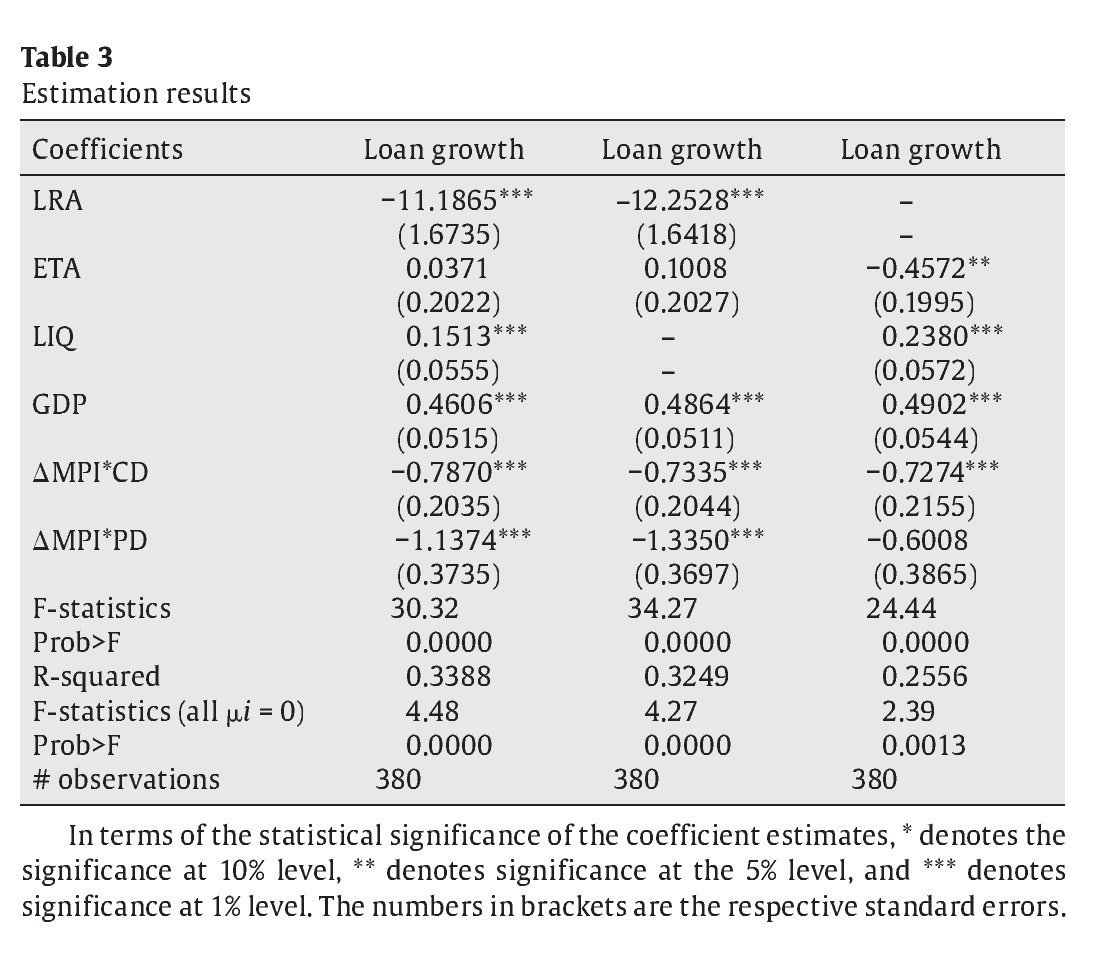

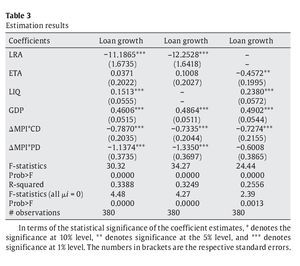

Estimation results are given in Table 3. In the second column all related bank specific variables are included in the model. As an alternative specification, the model is also estimated using alternative sets of bank specific variables. These estimations are shown in columns three and four. The bank specific fixed effects are not reported here, but the F-statistics related with the joint signifi cance of these effects is significant at 1% level under all alternative specifications. The F-statistics for the overall significance of the model is reasonably high and the R-squared of the regression is 0.34 under the baseline specification.

In terms of bank specific variables, the results show that, under all specifications where they are included, asset size and the ratio of liquid assets to total assets are significant variables. It is seen that smaller banks tend to have higher loan growth. This is consistent with the findings of Kishan and Opiela (2000) who investigate the response of U.S. bank to monetary policy and find that small banks are more responsive to changes in monetary policy. In terms of liquidity, more liquid banks are likely to have higher loan growth. Kashyap and Stein (2000) also find that U.S. banks that have lower ratio of cash and securities to total assets tend to be more affected by the lending channel of monetary policy. It is seen in the second and third column that the ratio of equity to total assets does not seem to be a significant bank specific characteristic that affects loan growth. The ratio of equity to total assets is only significant under the third specification where asset size is not included in the model.

The response of commercial banks and participation banks to lending channel of monetary policy is measured by the change in monetary policy instrument that interacts with the respective dummy variables for both types of banks. The coefficients ofΔMPI · CD and ΔMPI · PD are both negative under alternative specifications implying that an increase in overnight lending rate, which is the monetary policy instrument here, leads to a decline in loan growth of both commercial banks and participation banks. That is, the lending channel of monetary policy works for Turkish banking sector. However, the results reveal that the reactions of commercial banks and participation banks are not the same. To be more specific, our baseline estimation shows that, for commercial banks, 1% increase in overnight lending rate of central bank is expected to generate a 0.79% decline in quarterly loan growth. On the other hand, participation banks show larger reaction to the lending channel of monetary policy. Numerically, 1% increase in overnight lending rate is expected to reduce the quarterly loan growth of participation banks by 1.14%.

3.2. Policy implications

One can derive th ree important policy implications related to the Turkish banking sector from the results obtained in this paper. First of all, for a combined sample of commercial banks and participation banks, bank specific variables affect the lending channel of monetary policy. It is found that small banks and banks with higher ratios of liquid assets to total assets tend to have higher loan growth. In terms of asset size, this shows us that, for Turkish banks, small banks are more aggressive in terms of their loan growth. Another bank specific variable that affects bank lending is the ratio of liquid assets to total assets. The results show that banks that are more liquid are likely to have higher loan growth. This result is not surprising, as one could expect more liquid banks to respond less to monetary policy as they have more space to move in case of a monetary tightening.

Secondly, the results show that the lending channel of monetary policy works for Turkish economy. The coefficients for the change in monetary policy instrument, which is interacted with dummy variables for commercial banks and participation banks, are both negative. Therefore, when the Central Bank of Turkey wants to affect the total demand in the economy via the lending channel, banks show considerable reaction to changes in monetary policy instrument.

Thirdly, the results provide evidence that there is a difference in the reactions of commercial banks and participation banks to the lending channel of monetary policy. It is found that participation banks are more responsive to monetary policy shocks in terms of their loan growth. One can conjecture that this may be due to the operating nature of these banks. Participation banks operate according to Islamic rules and they are basically doing interest-free banking. Therefore, in comparison to commercial banks, they are more restricted in terms of their funding alternatives. For instance, participation banks cannot borrow in the form of syndicated loans which is an important source of external finance for Turkish banks. So limitation in funding alternatives could make participation banks more responsive to monetary policy shocks in terms of their lending.

4. Conclusion

In this paper I investigat e the lending channel of monetary policy for the Turkish banking sector for the period from 2006 to 2010 and whether banks' reactions change according to their type. In particular, I looked at whether commercial banks and participation banks respond differently to changes in monetary policy instrument. At the same time, I verified some bank fundamentals that are assumed to affect bank lending.

In terms of bank specific variables, the results reveal that asset size and liquidity affect bank lending. In particular, small banks and banks that have higher ratio of liquid assets to total assets tend to have higher loan growth. This result is consistent with other studies carried out for U.S. banking sector and other economies.

The results also reveal that lending channel of monetary policy works for Turkish economy for a combined sample of commercial banks and participation banks. That is, an increase in overnight lending rate by the central bank generates a reasonable decline in loan growth of Turkish banks. However, there are important differences in the responses of commercial banks and participation banks. On average, participation banks tend to be more responsive to monetary policy shocks, whereas commercial banks are less influenced from the lending channel of monetary policy. One could attribute this difference to the operating nature of participation banks which operate according to Islamic rules and therefore, have limited funding opportunities compared to commercial banks.

1. Aydin and Igan (2010), Catik and Karacuka (2011), and Alper at al. (2012) are some other examples who study the lending channel of monetary policy for Turkish banking sector.

2. I do not take into account investment and development banks when looking at whether the lending channel of monetary policy changes depending on bank type. The reason is that, as opposed to commercial banks and participation banks, these banks are not entitled to collect deposits and this might create a significant difference.

3. The data for commercial banks include the largest 15 commercial banks which account for more than 97% of total loans for commercial banks.

Article history:

Received March 26, 2012 Accepted August 25, 2012

E-mail address:

fmacit@ssu.edu.tr (F. Macit).

References

Alper, K., Hulagu, T., Keles, G., 2012. An empirical study on liquidity and bank lending. Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey Working Paper 4.

Aydin, B., Igan, D., 2010. Bank lending in Turkey: Effects of monetary and fiscal policies. IMF Working Paper 233.

Bhaumik, S.K., Dang, V., Kutan, A.M., 2011. Implications of bank ownership for the credit channel of monetary policy transmission: Evidence from India. Journal of Banking and Finance 35, 2418-2428.

Catik, A.N., Karacuka, M., 2011. The bank lending channel in Turkey: Has it changed after the low inflation regime. DICE Discussion Paper 32.

Gambacorta, L., 2005. Inside the bank lending channel. European Economic Review 49, 1737-1759.

Hausman, J.A., 1978. Specification test in econometrics. Econometrica 46, 1251-1271.

Kashyap, A.K., Stein, J.C., 1995. The Impact of monetary policy on bank balance sheets. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 42, 151-195.

Kashyap, A.K., Stein, J.C., 2000. What do a million observations on banks say about the transmission of monetary policy. American Economic Review 90, 407-428. Kishan, R.P., Opiela, T.P., 2000. Banks size, bank capital and bank lending channel. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 32, 121-141.

Kishan, R.P., Opiela, T.P., 2006. Bank capital and loan asymmetry in the transmission of monetary policy. Journal of Banking and Finance 30, 259-285.

Macit, F., 2012. Does bank ownership affect the credit channel of monetary policy. Suleyman Sah University, Working Paper.

Olivero, M.P., Li, Y., Jeon, B.N., 2011. Competition in banking and the lending channel: Evidence from bank level data in Asia and Latin America. Journal of Banking and Finance 35, 560-571.

Peek, J., Rosengren, E., 1995. Bank regulation and the credit crunch. Journal of Banking and Finance 19, 679-692.

Stein, J.C., 1998. An adverse-selection model of bank asset and liability management with implications for the transmission of monetary policy. RAND Journal of Economics 29 (3), 466-486.