This article proposes that artificial intelligence (AI) is positioned as a key driver of a new evolutionary stage of human knowledge, complementing human intelligence and facilitating the creation and development of sophisticated collective intelligence, defined as the noosphere, understood as the sphere of collective human thought. The study reveals several key insights into the transformative potential of AI, including its capacity to accelerate, mediate, and diffuse human knowledge. It concludes that AI not only catalyzes the existence of the noosphere but also redefines the structures and mechanisms through which human knowledge is expanded and democratized. Additionally, the document presents potential risks and significant ethical, social, and legal challenges of an AI-mediated noosphere, offering recommendations and a research agenda around the topic, and limitations and proposals for improvement to be considered in the future.

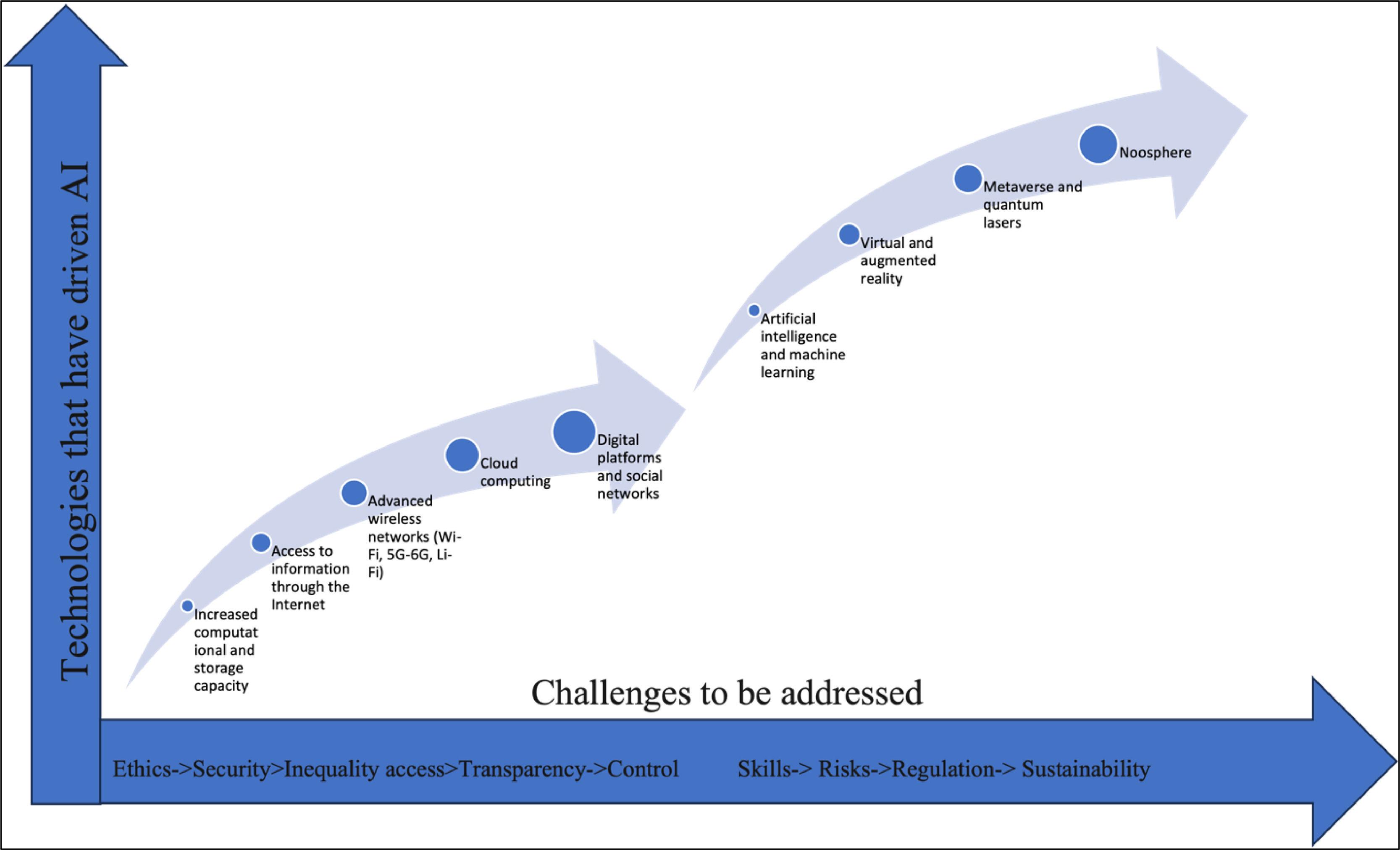

In the last 20 years, technological advances in computational power, storage capacity, access to information through the internet, the ability to generate content through digital platforms and media, social networks and growing global interconnectivity have provided new capabilities for humanity to generate knowledge (Ajani et al., 2024).

This is driven by the development of telecommunications technologies (such as fiber optics, satellites, and wireless technologies such as Wi-Fi, 5G-6 G, Li-Fi, and quantum-dash lasers), which allow the transmission and reception of an ever-increasing volume of data and enable new ways of interacting with information. This technological evolution allows the fast and reliable transmission of large volumes of data, thus facilitating wider and more efficient access to information in various formats (Kizza, 2024).

Moreover, the expansion of information networks, cloud computing, and online platforms, along with the proliferation of mobile devices, has democratized the exchange of information, facilitating access and knowledge creation (Gill et al., 2022). On the other hand, computational power increases with each new generation of PCs and culminates in the realization of quantum computers, which promises to revolutionize modern computing by providing processing capabilities that are inconceivable from current technology (de Wolf, 2017; Fauseweh, 2024; Ladd et al., 2010).

Additionally, the development of the metaverse, which represents a convergence of virtual worlds, augmented reality, and the internet, offers an advanced and immersive experience in 3D environments, providing new ways of generating and sharing knowledge (Yu, 2024).

These advances have contributed to creating a more interconnected world, where traditional limitations of distance and time have been considerably reduced, redefining the way society accesses, shares, and consumes information and creates new knowledge. They have also impacted various business paradigms. In the business realm, digitalization has enabled the creation of new business models based on digital platforms and social networks, enhancing globalization and interconnectivity (Hu et al., 2024).

Technological elements have recently enabled the accelerated development of artificial intelligence (AI). A new generation of information technologies can be defined as the use of techniques, technologies and application systems to replicate, improve and augment human intelligence and have revolutionized sectors such as health care, education, and finance; optimizing processes; improving decision-making; and managing uncertainty in companies' decisions (Liu et al., 2024). The technical concepts and applications of artificial intelligence, such as ChatGPT (Fosso Wamba et al., 2024), blockchain Dhar Dwivedi et al. (2024) and predictive maintenance (Ucar et al., 2024), have been widely addressed by scholars; therefore, this paper contributes to the literature from a theoretical perspective through several distinctive elements, such as the noosphere.

The integration of AI into the business realm has significantly transformed business models, driving efficiency and enhancing global market responsiveness (Mishra & Tripathi, 2021). AI has enabled process automation, optimized decision-making, and better management of uncertainty, thereby boosting competitiveness and innovation in key sectors such as finance, logistics, and health care (Enholm et al., 2022). This phenomenon not only improves operational productivity but also creates new opportunities for value creation through the analysis of large datasets, and companies that have adopted AI have found new ways to identify consumption patterns and make more accurate predictions, leading to better adaptation of products and services to global market demands (Åström et al., 2022).

The planetary evolution of AI has been linked to specific sectors and countries. As Tran et al. (2019) mentioned, AI applications in the medical and health sciences sector have been led by the USA, China, Italy, Germany and Canada. According to Jha et al. (2019), South Korea, China, and North America have invested considerable sums in AI to improve their performance in terms of agriculture. The improvement in the sustainability of the mining industry has been catalyzed in part via innovation and artificial intelligence in countries such as China, Australia and Canada (Jenkins & Yakovleva, 2006; Liang et al., 2024). In the construction sector, AI is not only applied to improve the characteristics and construction methods of buildings but also used to prevent accidents in the construction of buildings in the USA (Zhang et al., 2013) and South Korea (Jo et al., 2017).

These elements help revive the idea of the noosphere, a concept that refers to the "sphere of human thought"—the collective intelligence of humanity—which we propose in this paper as the new evolution of human knowledge. In this context, AI, with its ability to process and analyze large amounts of data, interpret complex patterns, and learn, is positioned as an entity that can accelerate this new evolutionary stage of knowledge (Wu, 2024).

It enables the emergence and mediates the development of this stage by adding a new substrate of information and knowledge generated by artificial intelligence, complementing that generated by human intelligence. The evolution of human knowledge can occur with or without AI (Lehoux et al., 2023); however, the dilemma posed in this work is the possibility that humanity may be left on the sidelines of this new stage if it is unable to evolve its cognitive capacity and develop the necessary skills to interact with AI and this new space of shared knowledge.

The general objective of this research is to analyze and evaluate the role of artificial intelligence as a potential catalyst in the evolution of human knowledge toward the establishment of sophisticated collective intelligence, called the noosphere, and to explore the ethical, social, and legal challenges associated with its integration into the knowledge society.

The document reviews theories around the evolution of knowledge developed by Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, Francisco Varela, and Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, which present different perspectives on how and why human knowledge has evolved and what could be expected in the future. This paper presents elements of the noosphere and the hypothetical role of AI as a mediator of this new evolutionary stage of human knowledge, focusing on how this advanced technology could facilitate a deeper and more meaningful connection of human knowledge on a global scale.

To develop a comprehensive understanding of the role of AI in the evolution of human knowledge and its integration into the noosphere, a systematic search strategy was employed. This strategy involved a multidisciplinary approach, obtaining literature from fields such as computer science, ethics, sociology, and neuroscience, and theoretical developments by authors, who reflected on the evolution of human knowledge to ensure a broad but specific collection of relevant materials.

The research questions include the following. a) How can artificial intelligence accelerate the evolution of human knowledge and facilitate the development of the noosphere? b) What role does it play in this process? c) What are the main ethical, social and legal risks associated with the integration of AI in the noosphere, and how can they be mitigated? d) How can humanity adapt to benefit from this technology?

The main contribution of this research is related to addressing the following gaps in the literature by reflecting theoretically. First, there is a limited understanding of how AI technologies can configure a new space of collective knowledge and thus accelerate the evolution of human knowledge toward new forms of understanding, new forms of generation, collaboration and dissemination of knowledge. Second, there is limited research on the social and cultural impacts of AI integration in global knowledge networks. This gap is addressed by examining how AI can influence cultural exchange and social dynamics within knowledge networks and its potential to foster global collaboration and the dissemination of human knowledge. Third, there are insufficient regulatory frameworks to manage AI risk and ensure its alignment with human values at the global level. This research addresses this gap by developing policies to regulate AI use, ensuring ethical and fair AI operations, and involving a wide range of stakeholders in AI policy development.

Finally, there is uncertainty about the long-term impacts of AI on the evolution of human knowledge (Means, 2021; Nordström, 2022). This gap is addressed by evaluating the ongoing influence of AI and forecasting future scenarios of AI integration in the noosphere. By addressing these knowledge gaps, this research aims to provide a deeper understanding of the role of AI in the evolution of human knowledge and to consider the potential risks associated with AI integration.

The document was developed as follows. In the first section, the topic, its relevance and the methodological approach and questions that guide the research are introduced. In the second section, a brief theoretical framework is developed that refers to the evolution of human knowledge developed by different authors, focusing on the development of the concept of the noosphere proposed by Teilhard de Chardin and the hypothetical role of AI as a catalyst and mediator of this new evolutionary stage. The third section presents the ethical challenges posed by the AI-mediated noosphere. The fourth and fifth sections present the discussion and conclusions of the research, presenting aspects to be considered in future research related to the topic.

Theoretical frameworkThe evolution of human knowledge has been a central theme in understanding the progress of civilizations and the development of intellectual capacities. This section explores the theoretical underpinnings of knowledge evolution, focusing on how various paradigms have shaped our understanding of knowledge generation and dissemination. The framework provided here will examine the historical trajectory of knowledge, the mechanisms that have facilitated its expansion, and the emerging role of artificial intelligence as a catalyst in accelerating this process. By situating AI within the broader context of knowledge evolution, we aim to elucidate its potential impact on the development of the noosphere and the implications for human cognitive advancement.

The evolution of human knowledgeThe evolution of human knowledge refers to the historical and ongoing process through which human knowledge has grown, changed, and been refined over time. This concept encompasses the accumulation of information, the improvement of cognitive abilities, and the development of methods and technologies that facilitate the creation, storage, and transmission of knowledge.

Knowledge is different from data and information; data are unstructured facts, information consists of structured data, and knowledge is the ability to judge and use information to define problems and solve problems (Lambooy, 2004).

Advanced cognitive capacities in humans evolved as a consequence of stronger selection for the efficient transmission of knowledge, and the result was language and the emergence of more sophisticated collective intelligence, which facilitated a shared intentionality and a cumulative cultural process due to increased pressure for efficient cultural transmission (Migliano & Vinicius, 2021).

The evolution of human knowledge and the processes of discretization and synthesis in relation to the increase in knowledge are also part of this analysis (Wilson, 2017). Other authors, such as Georgescu-Roegen, Francisco Varela and Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, have considered this aspect of knowledge.

Georgescu-Roegen develops the idea of the evolution of knowledge through science (Georgescu-Roegen, 1971), where he mentions memory as the storehouse of knowledge and writing and its means of recording (papyri, paper, stone, etc.) as a mechanism for transmitting knowledge from generation to generation and the processes of classifying knowledge as a mechanism for rapid access to specific knowledge.

Over the centuries, these biological and material mechanisms for storing knowledge have evolved and made their storage and transmission more complex. Georgescu-Rogen considered that the logical evolution of science, which generates current knowledge, will be the knowledge generated by electronic brains, which will have the capacity to store information (digital memory) and its classification and transmission and to do so faster and more efficiently than a human being can.

Glimpsing in his book published in 1971 what we now understand as AI. In this context, Ruth Davis warns that more efforts are currently being devoted to improving computers than to perfecting the human mind and that this condition will be aggravated by automatons that will have the ability to synthesize knowledge faster and more efficiently than human beings.

Nevertheless, the creative faculties of the human being to discover the regularities of reality, devise new concepts with which to synthesize apparently diverse facts, and formulate and demonstrate propositions are still of exclusive human formulation. However, science is a living organism that reproduces, grows and preserves itself; if AI begins to mediate its development, there is a risk of altering the substantial mechanisms of generating human knowledge and propelling it to new states, different from those possibly reached by human beings, particularly if human beings abandon their contemplative capacity and idle curiosity, which has made the generation of human knowledge possible.

Varela, on the other hand, mentioned that human knowledge and memory are aspects of human consciousness, and the evolution of knowledge is explained through the concept of autopoiesis, developed in collaboration with Humberto Maturana (Maturana & Varela, 2009; Varela et al., 1974). Autopoiesis describes living systems as autonomous entities capable of maintaining and reproducing their organization through component production networks that continuously regenerate and specify the same network of processes. This concept has been crucial to understanding how living systems, including humans, self-organize and evolve.

In the evolution of knowledge context, Varela argues that cognitive processes cannot be understood solely as internal representations of the external world. Instead, he proposes a view in which cognition is an enactive process, that is, an active process of creating and transforming meaning through interaction with the environment. This enactive approach holds that knowledge arises from the codetermination between the organism and its environment, challenging the traditional dichotomy between the subject and the object (Varela, 2000).

Varela identified three key moments in the evolution of knowledge. The first is the development of the sensorimotor loop, which enables basic perception and action and is foundational to all animals. The second is structural plasticity, particularly in mammals, which allows adaptation and changes in response to environmental stimuli, contributing to behavioral and cognitive complexity. The third is the invention of language, which is unique to humans and facilitates coordination and communication within a species, enhancing cognitive and social capabilities (Keven Poulin, 2015; Maturana & Varela, 1992).

The evolution of knowledge according to Varela is intertwined with the development of life, and the ability of the cognitive system to adapt and change in response to new experiences and environments (plasticity of knowledge) is crucial to understanding how living organisms, including humans, can learn and evolve cognitively (for a deeper exploration of these ideas, Varela's work, "the embodied mind", extends these concepts by integrating them with phenomenology and discussing the importance of structural plasticity in shaping cognition in response to environmental stimuli, Varela et al., 1991, 2017). AI can accelerate the next evolutionary phase of knowledge, which involves greater integration and complexity in how cognitive systems interact with their environment and each other.

Given that human memory is the manifestation of structural modification, which is closely related to learning, the noosphere, as a space for the development of this fourth evolutionary moment of knowledge, can change our understanding of what we currently understand as digital memory, which is binary and records knowledge transformed into language, to a greater state of understanding of the environment and humanity itself. It is an active process of engaging with past events in the present rather than a static repository of information.

Different types of memory (associative, episodic) are linked to the evolution of the brain. Varela warned against two major pitfalls in the understanding of knowledge: the certainty that the world is fixed and immutable, leading to dogmatism and inflexibility, and the mistaken idea that rationality and emotion are distinct when they are inherently intertwined in cognitive processes. The noosphere would allow the evolution of multiplexed memory, enabling the integration of knowledge, its rapid access, and its complex development, which would allow intelligent systems (humans and machines) to interact with each other.

Here, the challenge must be undertaken by humans, who should develop their cognitive abilities through education that emphasizes flexibility and adaptability over mere content acquisition. This implies methods that integrate the body and emotion into the learning process to foster deeper understanding and retention. According to Varela, true autonomy involves the capacity for self-organization and adaptation within constraints, not just independence from external influences. Communication and language are seen as internal reorganizations of interacting systems, creating shared meaning rather than merely exchanging information.

In this evolutionary process of knowledge, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin proposes a new evolutionary phase in which a new space of interaction of human knowledge is configured, which he calls the noosphere, of which we briefly develop its characteristics below.

Noosphere: the space of human knowledgeThe noosphere is considered the collective development of consciousness and knowledge (Peters & Reveley, 2015), a layer that has emerged through the interaction and accumulation of human knowledge and is characterized by the presence and predominance of human thought.

It can also be understood as a superorganism, which is not composed of human brains but of a brain of brains, where each component of the collective brain is itself a center of reflection. Unlike other natural superorganisms (such as termite mounds, anthills, and beehives), which are organized around a familial structure, the human noosphere or superorganism is based on the extraordinarily binding property of thought, which can unite genetically unrelated individuals into functionally organized groups (Wilson, 2023).

The term is derived from the Greek νοῦς ("nous") meaning "mind" and σφαῖρα ("sphaira") meaning "sphere.” The concept of the noosphere, originally coined concurrently by Russian geochemist Vladimir Vernadsky and French Jesuit paleontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin in the mid-20th century, is broadly interpreted as the world transformed by humans and human thought. Vernadsky defined it as the physical manifestation of human thought in the biosphere, the world transformed by man (Wyndham, 2000). Chardin described the noosphere as the thinking layer; outside and above the biosphere, the noosphere exists (Chardin, 1964).

Additionally, it has been proposed that the internet is the medium that brings the noosphere to life, speculating on the possibility of a hypothetical machine, called the "Nooscomputer" or N-computer, which would consume less energy and allow civilization to reach the point of technological singularity and the emergence of human‒machine superintelligence (Lahoz-Beltra, 2018). In the noosphere context, the “omega point,” expressed as the end to which human knowledge converges, can be defined in the context of the concept of Teilhard de Jardin Florio, (2016), which conceptualizes the natural evolution of how human knowledge not only integrates but also transforms human reality.

The existence of this space may imply several aspects in the generation and transmission of human knowledge, as follows (see Table 1).

Key Aspects of the Noosphere and Its Impact on Human Knowledge and Society.

| Aspect | Description | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Connectivity and Interconnection | The noosphere suggests a high degree of connectivity and interconnection among individuals and societies, which facilitates the rapid and efficient exchange of information and knowledge. | (Shoshitaishvili, 2021) |

| Collective Consciousness | The noosphere integrates knowledge and transcends areas and disciplines, leading to a deeper understanding of knowledge—from knowing to understanding and experiencing. | (Arguelles, 2011; Beigi & Heylighen, 2021) |

| Integration of Human Knowledge | Implies the existence of a collective consciousness or shared understanding, where the knowledge and experiences of individuals are integrated into a broader network of human knowledge. | (Peters & Reveley, 2015) |

| Evolution of Knowledge | The noosphere could accelerate the evolution of knowledge, stimulating new ways of organizing knowledge and new ways of using knowledge | (Chernikova et al., 2021) |

| Impact on understanding Knowledge and Learning | The existence of a noosphere could transform the way we learn and teach. It makes it possible to improve the cognitive abilities of the human being, personalizing access to knowledge according to the needs and learning styles of each individual | (Goncharenko et al., 2020) |

| Solving Global Problems | The noosphere could facilitate global collaboration in problem-solving, leveraging collective wisdom to address global challenges of interest to humanity or that threaten its existence, such as: climate change, sustainable development, and the survival of humanity in the face of pandemics or disasters. | (Gorbachev et al., 2012; Turkov, 2019) |

| Creation of New Forms of Interaction | The noosphere may generate new forms of interaction between humans and their knowledge in society. | (Houben et al., 2013; Shoshitaishvili, 2021) |

Source: the authors.

Table 1 shows key aspects of the noosphere in the knowledge society. In particular, the noosphere suggests a high degree of connectivity and interconnection among individuals and societies. This interconnectedness is fundamental because it facilitates the rapid and efficient exchange of information and knowledge. In a globally connected world, barriers to information flow are minimized, enabling not only faster communication but also the synthesis of diverse ideas across different cultures and disciplines. This ubiquitous connectivity can lead to an accelerated pace of innovation and a deeper understanding of global issues.

The noosphere integrates knowledge from various domains and transcends traditional disciplinary boundaries. By fostering an environment where knowledge from disparate fields can merge, the noosphere contributes to a richer, more comprehensive understanding of complex phenomena. This integration moves us from basic knowledge acquisition to deeper comprehension and experiential learning, facilitating a more enlightened approach to education and intellectual inquiry that is reflective of a truly interconnected world.

The emergence of a collective consciousness through the noosphere implies a shared understanding and pooling of knowledge among individuals. This phenomenon expands the cognitive reach of individuals by providing access to a vast network of human experiences and insights. As a result, decision-making becomes more informed and nuanced, reflecting the collective wisdom accumulated over generations and shared through contemporary digital platforms.

By enabling faster synthesis and collective enhancement of ideas, the noosphere plays a pivotal role in the evolution of knowledge. It not only accelerates the pace at which knowledge is generated but also enhances the quality of outputs by leveraging collective intellectual resources. This dynamic environment encourages continuous innovation and adaptation, which are crucial for addressing the rapidly changing needs of society.

The noosphere's facilitation of global collaboration positions it as an essential tool for solving complex global challenges such as climate change, sustainable development, and pandemic response. By harnessing collective wisdom, the noosphere enables a more cohesive and coordinated approach to problem solving that transcends national and cultural barriers, potentially leading to more sustainable and effective solutions.

The noosphere encourages the development of new modes of interaction between humans and their collective knowledge. These new modes of interaction not only make knowledge more accessible but also the possibility of accessing collectively enriched knowledge, potentially altering the way knowledge is consumed and utilized in society. This signifies change in the way that knowledge is interconnected, applied and integrated, and its advancement holds the potential to create sophisticated collective intelligence that can stimulate creative problem-solving complexes and broaden our comprehension of the knowledge that currently exists and opens new ways of understanding and generating knowledge. An initial example of this type of knowledge could be experienced with respect to the COVID-19 pandemic, where collective effort made it possible to solve a difficult puzzle in a short time (Wu et al., 2024).

However, there are also ethical and privacy challenges that these characteristics pose to humanity. With such a high level of interconnection, questions arise about moral aspects concerning knowledge management, privacy, knowledge control, and ownership of knowledge/copyright, as well as the ethical management of a vast network of shared knowledge that enables the transition from a knowledge society to a society of understanding.

Wilson (2017) presented a system integrating the biosphere, noosphere and technology. We argue in Fig. 1 that organisms and systems increase their amount of interaction depending on an increase in complexity, as has already been examined by many writers.bib48

The noosphere represents a significant evolution in the way knowledge.

An intermediate state of complexity in which relationships occur in the noosphere without technology, connected to Teilhard de Jardin's studies; finally, we propose a state mediated by technology, where relationships occur through a metaverse in the Technosphere. This primary state of physical complexity is illustrated by Vernadsky's biosphere (Vernadsky, 1945), and the relationships of biological self-dependence are closely related to the autopoiesis of Maturana and Varela (Varela et al., 1974).

The concept of the noosphere has been criticized. Galleni and Groessens-Van Dyck (2017) mentioned that its religious origin can make conversation with other areas that use the concept difficult. Wilson (2017) argues that it can be confused with the biosphere, especially if we consider Venadsky's concept, and Lahoz-Beltra (2018) criticizes the noosphere, which can function as a limiting factor to reach the point of technological singularity related to artificial intelligence.

The existence of a noosphere would have profound implications for the way we generate, share, and use knowledge, potentially transforming the social, educational, and technological structures of our society and posing significant challenges to humanity. The mediating role of AI in the noosphere introduces a range of potential risks that need careful consideration and management. We address these challenges in the next section.

AI as a bridge of the noosphereAI is positioned as a transformative agent in the realm of human knowledge. This technology is not only a tool for automating processes or analyzing large volumes of data but also a crucial bridge for connecting and expanding humanity's collective wisdom. How can artificial intelligence accelerate the evolution of human knowledge and facilitate the development of the noosphere, and what role does it play in this process? AI can play a key role in the development of the noosphere in two essential aspects, such as becoming an integrating agent of human knowledge and a mediating agent of this new space, which are described below.

AI as an integrating agent of humanity's knowledgeOne of the most impactful aspects of AI is its ability to process and analyze data at a scale and speed that far exceeds human capabilities (Dwivedi et al., 2021). This not only allows for a better understanding of patterns and trends across various areas of knowledge but also enables the discovery of relationships and insights that were previously inaccessible. For example, in the field of medicine, AI can analyze millions of patient records to identify trends and correlations that may lead to new treatments and therapies (Lin & Wu, 2022).

Additionally, AI democratizes access to knowledge and enables its creation. Through adaptive learning systems and personalized educational platforms, AI can provide tailored learning experiences to individuals worldwide, regardless of their geographical location or economic resources. This not only enhances education and training but also enables a larger number of people to contribute to the global knowledge pool (Maghsudi et al., 2021).

AI is also transforming the way we interact and collaborate. AI-driven communication platforms facilitate connections between individuals and groups with common interests and goals, overcoming linguistic and cultural barriers (Ogie et al., 2018). This fosters more effective collaboration and faster dissemination of knowledge and ideas. AI can facilitate communication and connectivity on a global scale, overcoming language and geographical barriers, and automatic translation systems and virtual assistants can enable smoother and more comprehensible interactions between people from different regions and languages and improve communication and connectivity (Zemplényi et al., 2023).

AI technologies can enhance collaboration platforms, fostering the creation of online communities where information and knowledge are exchanged, and collaborative projects are conducted on a global scale to solve problems and challenges as a human species, realizing one of the purposes of the Noosphere (Peters & Reveley, 2015).

Through virtual and augmented reality and devices that interact with humans, AI can create new forms of interaction, where immersive environments for education, work, and leisure offer new ways to experience and share knowledge (Lehman-Wilzig & Lehman-Wilzig, 2021).

AI is emerging as a catalyst for human knowledge, facilitating broader and deeper access to knowledge, enhancing global collaboration and communication, and accelerating innovation and discovery (Holstein et al., 2020; Jarrahi et al., 2023).

AI as a mediator of the noosphereAI can not only enable the existence of the noosphere but also facilitate the evolution of the way knowledge is generated, acting as a mediating entity of the knowledge that is developed by humanity. This mediating role of AI enhances interconnection and information exchange, promoting a collective consciousness and a transdisciplinary integration of knowledge (Peters & Reveley, 2015).

Through enhanced communication platforms and data analysis, AI enables the formation of global virtual communities and fosters a holistic understanding of human knowledge, aligning with the noosphere's objectives to overcome disciplinary divisions and foster knowledge synthesis (Hall & Kilpatrick, 2011).

AI innovates in creating new forms of interaction and communication, stimulating the evolution of social and cultural dynamics. This role of AI not only redefines the way we interact with knowledge and each other but also reinforces the idea of the noosphere as a constantly evolving entity, expanding and deepening through the integration of technology into the fabric of human collective consciousness. In Table 2, we explore several of these aspects, which summarize the dimensions of the noosphere that are likely to be affected by the development of AI and the emerging tools and technologies that are enabling mediation.

Summary of the dimensions of the sphere of knowledge and the possible mediating effects of AI and emerging AI tools and technologies.

| Dimensions | AI | Emerging AI Tools and Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| Connectivity and Interconnection | Overcomes language and geographical barriers, facilitating global communications through automatic translators, virtual assistants and virtual collaborator/mentor. | Natural language processing (NLP) is a branch of artificial intelligence, which combines computational linguistics, machine learning, and deep learning models to process human language (ChatGPT, Bing, Bard, etc.). Neural Networks: Frameworks such as (TensorFlow, PyTorch) |

| Collective Consciousness | Enhances social networking and collaboration platforms, creating online communities for information exchange and collaboration on global projects. | AI-driven Collaboration Tools for enhancing team collaboration (Miro AI, Notion AI) and Community Platform. |

| Integration of Human Knowledge | Analyzes and synthesizes data from multiple sources, facilitating interdisciplinary discoveries and advancements. | It allows users to extract, analyze, and synthesize large volumes of information from multiple sources (IBM Watson Discovery, Google DeepMind's AlphaFold, Microsoft Azure Synapse Analytics, Zymergen, Semantic Scholar). Quantum Computing for solving complex problems (IBM Quantum System One, Google's Sycamore) |

| Evolution of Knowledge | Stimulating new tools for organizing knowledge and new ways of using it | knowledge-organizing technology (KGs, and SGs) |

| Impact on understanding knowledge and Learning | It makes it possible to improve the cognitive abilities of the human being, personalizing access to knowledge according to the needs and learning styles of each individual | Adaptive Learning Systems: Technologies like Knewton and Smart Sparrow for personalized education. AI Tutors: Tools like Squirrel AI and Century Tech offering tailored learning experiences and real-time feedback. |

| Solving Global Problems | Facilitate global collaboration in problem-solving, leveraging collective wisdom to address global challenges of interest to humanity or that threaten its existence | |

| Creation of New Forms of Interaction | Drives creativity and innovation, may generate new forms of interaction between humans and their knowledge in society. | Virtual Reality (VR): Emerging platforms like Oculus Quest 3 and HTC Vive Pro 2 for immersive learning and interaction. Augmented Reality (AR): Tools like Microsoft HoloLens and Magic Leap for enhancing real-world environments with digital information. |

Source: Authors' own elaboration.

AI emergence technologies, such as advanced neural network-based models designed to generate human-like text on the basis of the input they receive (GPT-4, BERT, etc.), play crucial roles in overcoming language barriers and facilitating global communication through advanced natural language processing (Panchendrarajan & Zubiaga, 2024). Additionally, neural networks are designed to recognize patterns and learn from large volumes of data and thus solve complex tasks (Lapo & Cumbicus-Pineda, 2024).

AI can facilitate collaboration through social media and collaboration platforms that allow people to exchange ideas and work together on global projects (tools such as Miro AI and Notion AI), allowing collaboration and recently becoming a collaborator (Schmutz et al., 2024). An online community platform is a digital space where individuals with shared interests, goals, or identities gather to interact, share information, and collaborate virtually. These platforms serve as hubs for fostering connections, discussions, and the exchange of ideas among members, and AI can manage knowledge bases and solve problems between users, becoming a specialized assistant of the community (Kim et al., 2023).

High-profile successes deploying AI in domains such as protein folding have highlighted AI's potential to unlock new frontiers of scientific knowledge by analyzing and synthesizing data from multiple sources, leading to interdisciplinary discoveries, synthesizing information from various disciplines to create a comprehensive understanding of complex issues, integrating human knowledge and positioning AI as a catalyst for scientific discovery (Lawrence & Montgomery, 2024). However, to consolidate these AI developments, an open data science environment that provides the benefits of AI in all areas of the sciences is needed. Tools emergent for AlphaFold, IBM Watson Discovery, Google DeepMind's, Microsoft Azure Synapse Analytics, Zymergen, Semantic Scholar.

AI can facilitate the creation of technologies that allow knowledge organizations to help breakdown silos and facilitate the identification and access of existing relevant siloed knowledge (Lotz et al., 2023). Recent work has explored the current capabilities of knowledge integration technologies (large language models (LLMs), similarity graphs (SGs), and knowledge graphs (KGs)).

As Varela noted, a current challenge is the need for human beings to improve their cognitive abilities, along with developments in AI. In this sense, there are now various technologies that make it possible to personalize access to knowledge according to the needs and learning styles of each individual (Pesovski et al., 2024). This implies methods that integrate the body and emotion into the learning process to foster deeper understanding and retention and training the plasticity of the brain, creating shared meaning rather than merely exchanging information.

AI can facilitate the interaction of knowledge in the noosphere to be efficient and fluid, generating synergy in scientific collaboration and technological progress through tools that facilitate the location of relevant knowledge and improve the understanding of multidimensional problems that afflict or may afflict humanity in the future, facilitating faster findings. An incipient example of this level of deep collaboration around a global challenge was the COVID-19 pandemic, which challenged humanity to find an effective cure in the shortest possible time (Wu et al., 2024).

Technologies such as virtual reality (VR) offer immersive learning environments that transform how knowledge is experienced and shared. Similarly, augmented reality (AR) enhances real-world environments with digital information, creating new opportunities for interaction and collaboration that bridge the physical and digital worlds. The metaverse will harness advancements from various technologies, such as artificial intelligence, extended reality (XR) and mixed reality (MR), to provide personalized and immersive services to its users and generate new forms of interaction between humans and their knowledge in society (Alkaeed et al., 2024; Schmidt et al., 2024).

These emerging AI tools and technologies are not just supporting the dimensions of the noosphere—they are actively expanding and transforming them. The transformative potential of AI in the noosphere, as outlined in Table 2, demonstrates how emerging technologies drive connectivity, innovation, and knowledge integration. However, this same potential results in significant ethical and social risks that must be carefully managed.

AI, therefore, is not only a tool within the noosphere but also a transformative element that redefines and expands its capabilities and reach (Upreti, 2023). The idea of a noosphere mediated by AI raises numerous ethical challenges, risks, and dangers, as well as significant social implications (Jasečková et al., 2022), as proposed in Fig. 1.

One of the main risks associated with AI as a mediator in the noosphere is the potential concentration of control over AI systems themselves (Tweed, 2018). If these systems are predominantly developed and controlled by a few large tech companies or states, there could be an unprecedented centralization of power over how knowledge is selected, shared, and accessed. This centralization could lead to a monopolization of the "marketplace of ideas," where certain narratives are promoted over others, which could stifle diversity and plurality in global knowledge (Ingber, 1984).

Another risk is related to data privacy and security, as AI systems require access to vast amounts of personal data. The risk extends beyond mere unauthorized access to data and includes concerns about how data are used to shape individual and collective knowledge experiences. Without strict safeguards, the potential for surveillance and manipulation of cognitive and learning processes could pose a serious risk to the autonomy and evolution of knowledge (Lee & Petrina, 2018).

AI systems, to the extent that they are trained without regard to ethical principles to safeguard the occurrence of systemic biases in training data, can lead to AI-mediated knowledge that perpetuates existing biases (Anderson & Anderson, 2007; Mantatov & Tutubalin, 2018). In addition, the potential for AI to unintentionally spread misinformation due to algorithmic errors or vulnerabilities could lead to widespread misconceptions and hinder informed decision-making on a global scale.

Adding to this difficulty, the scarcity of variety in massive databases, which facilitates the development of diverse intelligence, can lead to segmentation of knowledge and segregation of those who cannot access these sources of information, limiting the potential development of knowledge (Fox, 2017). Here is the risk of commodifying access to the knowledge space and thus limiting the development of knowledge that is utilitarian and economically valuable to the detriment of necessary knowledge linked to the common good and universal benefit (Verdegem, 2022).

Another present risk is that the increasing reliance on AI to mediate knowledge and learning processes could lead to a decline in critical thinking and problem-solving skills among humans. This dependency could lead to a scenario in which humans are less capable of thinking independently and are overly dependent on AI for cognitive and intellectual tasks, which could lead to a degradation of human intellectual capabilities over time and limit the evolutionary developmental capabilities of the noosphere.

These risks are in addition to those currently discussed in the literature, such as the following. a) Ethics and biases: AI can perpetuate and amplify existing biases in training data, leading to unfair and discriminatory decisions (Giovanola & Tiribelli, 2023). b) Data privacy and security: AI requires large amounts of personal information, which raises concerns about data privacy and security (Ntoutsi et al., 2020). c) Inequality in access to technology: there is a risk that AI will exacerbate inequalities if it is available only to certain populations (Müller, 2014). d) Transparency and explainability: the need to improve the transparency and explainability of algorithms to foster user confidence and acceptance (Felzmann et al., 2020). e) Monopolize and control AI: avoid monopolization and control of AI by a small number of large corporations, promoting diversity (Roche et al., 2023).

These challenges highlight the complexity of integrating AI into society in a way that maximizes its benefits and minimizes its risks, respecting fundamental human values and rights and ultimately helping the evolution of knowledge. Fig. 2 summarizes the challenges and risks considered previously.

Ethical challenges posed by the AI-mediated noosphereThere are ethical implications that need to be addressed in the eventuality that a space equivalent to the noosphere powered by AI and its ability to manage human knowledge is consolidated (Felzmann et al., 2020; Roche et al., 2023). In this sense, it is relevant to consider the main ethical, social, and legal risks associated with the integration of AI into the noosphere and how these risks can be mitigated through appropriate policies and regulations. We address these aspects below.

Ethical aspectsAlthough AI has the potential to democratize access to knowledge, there is also a risk that it could exacerbate existing inequalities. Disparities in access to AI technologies could lead to a digital divide where only certain populations benefit from AI-mediated advancements in knowledge, while others are left behind.

To mitigate these risks, a comprehensive framework involving robust regulatory standards, transparent AI development processes, and active participation from a broad spectrum of stakeholders is essential (Walz & Firth-Butterfield, 2019). Such measures would ensure that AI's integration into the noosphere is beneficial and equitable, supporting the collective advancement of global knowledge without compromising ethical standards or human values.

Figs. 1 and 2 present the relationship between complexity and ethics. We argue that when systems become complex, there is a greater ethical obligation. Addressing these ethical challenges is critical to ensuring that AI's role as a mediator in the noosphere contributes positively to the advancement of human knowledge and societal development. By establishing comprehensive ethical standards and regulatory frameworks, we can harness AI's potential while safeguarding fundamental values and promoting a sustainable and equitable knowledge ecosystem.

Artificial intelligence assumes a pivotal role in the management and generation of human knowledge. These challenges stem primarily from AI's influence on the flow and accessibility of information, its impact on collective consciousness, and its role in the evolution of human knowledge. First and foremost, access to massive amounts of training data and access to AI-enabled learning are at the forefront. The extensive data required to power AI within the noosphere necessitate robust safeguards to prevent the monopoly of knowledge (Safadi & Watson, 2023), ensuring free access to human knowledge, the heritage of all. Additionally, the consent and transparency regarding AI operations must be clear. Users should be fully aware of how their data are used and must have the ability to opt out of data collection, ensuring that their engagement with the noosphere remains voluntary and informed (Gasparini & Kautonen, 2022).

Another critical issue is the potential for bias and discrimination in AI algorithms (Giovanola & Tiribelli, 2023). AI systems often reflect the biases present in their training data, which could lead to skewed knowledge and reinforced societal inequalities within the noosphere. Proactive measures, including the diversification of training datasets and rigorous testing for bias, are essential for cultivating fairness and objectivity in AI-mediated interactions.

The impact of AI on collective consciousness implies that the noosphere does not experience restrictions regarding the type of thinking and lines of research to be developed or that the need to form new knowledge is instrumentalized. Moreover, the autonomy and human agency within the noosphere must be preserved. Overreliance on AI could undermine human intellectual engagement and decision-making capabilities. It is crucial to design AI systems that complement and augment human intelligence rather than replace it, thereby encouraging meaningful human contributions and maintaining individual autonomy (Edwards, 2021).

The sustainability of knowledge within an AI-mediated noosphere requires careful consideration. AI systems should be designed to support the diversity and growth of knowledge, avoiding narrow focuses on predominant or profitable information streams. Preserving a broad spectrum of knowledge and cultural expressions ensures that the noosphere remains a rich, dynamic repository of human understanding.

Social aspectsThe integration of AI into systems as complex and global as the noosphere could have profound social implications, such as changes in the nature of work, education, and social interaction (Holstein et al., 2020). A new dynamic in the relationship between technology and society might emerge, where collective decision-making and consensus formation could be significantly influenced by automated systems.

A noosphere can cause changes in how society functions, and if AI mediates this, it can cause significant shifts in relevant dimensions of contemporary society, such as the nature of work and the economy (Lee & Petrina, 2018). Education and training would need to adapt to prepare people for a world where AI is prominent, fostering complementary and adaptive skills.

The noosphere could dramatically transform educational methodologies by emphasizing collaborative learning and knowledge creation through networks and impact knowledge formation and learning. This shift promotes a more active, participatory learning experience where learners are not only consumers of information but also contributors to the collective knowledge base. Such an approach is likely to cultivate critical thinking and problem-solving skills, which are essential for thriving in a knowledge-driven economy.

The social integration of AI aims to mitigate potential conflicts or rejection. There is a need for more agile governance in overseeing emerging technologies such as AI and robotics. The use of governance coordination committees (GCCs) is proposed as a way to address the ethical and legal challenges associated with AI (Wallach & Marchant, 2019). Additionally, they suggest the implementation of new mechanisms to enforce "soft law" approaches to AI through coordinated institutional controls. This approach could be relevant for overseeing an AI-mediated noosphere, where ethical challenges and social implications are critical.

Legal aspectsThe integration of artificial intelligence as a mediator in the noosphere, a conceptual space where human knowledge is concentrated and managed, entails a series of legal considerations that must be addressed to ensure its ethical and equitable use (Walz & Firth-Butterfield, 2019). To ensure that AI operates ethically and fairly within the noosphere, it is essential to establish a robust regulatory framework that includes transparency in AI development. The association between complexity and legal challenges is shown in Fig. 1. We contend that there is a greater legal obligation as systems become increasingly complex. These legal issues are linked to various data management issues. The developing entities must be transparent about the algorithms and processes used, allowing for independent audits and oversight to prevent biases and discrimination in the system. It is crucial to involve a wide range of stakeholders, including academics, technology professionals, civil society representatives, and regulators, in the creation and monitoring of AI policies (Eynon & Young, 2021).

The handling of large volumes of data by AI in the noosphere requires strict data protection measures. Users must be fully informed about how their data are collected, used, and stored, and they must have the option to opt out of data collection at any time. Additionally, robust measures must be implemented to protect user data from unauthorized access and security breaches (Rooksby & Pigott, 1997). To mitigate the risk of biases in AI algorithms, diversifying training data is essential. The datasets used must be diverse and representative of all populations to avoid perpetuating inequalities. Continuous testing must be conducted to identify and correct biases in AI systems, ensuring that decisions are fair and equitable (Ntoutsi et al., 2020).

The democratization of access to knowledge through AI must be accompanied by efforts to prevent exclusion. Policies must be established to ensure that all populations, regardless of their geographical or socioeconomic status, have equitable access to AI technologies. Furthermore, initiatives must be implemented to provide resources and training in the use of AI technologies to disadvantaged communities (Dessimoz & Thomas, 2024).

Designing AI systems that complement human intelligence rather than replace it is vital. AI systems should be designed to support and enhance human intellectual capacity and decision-making, promoting meaningful contributions and individual autonomy. The noosphere must avoid restrictions on types of thinking and lines of inquiry, ensuring an environment that fosters creativity and the formation of new knowledge (Jarrahi, 2018).

The sustainability of the noosphere requires that AI support the diversity and continuous growth of knowledge. Ensuring that AI systems promote a wide range of knowledge and cultural expressions, avoiding narrow focuses that prioritize predominant or profitable information is fundamental. Knowledge should be considered a heritage of humanity, with free access and without monopolization of information (Scarano, 2024).

As stated previously, Fig. 1 illustrates how a transition from the biosphere to the noosphere and perhaps the technosphere is indicated by an increase in system complexity. This system's evolutionary path is mediated by our knowledge and how it is managed. The incorporation of AI in the management and mediation of knowledge within the noosphere presents significant legal and ethical challenges. Developing a comprehensive legal framework that includes regulatory standards, data protection, bias mitigation, equitable access, preservation of human autonomy, and sustainability of knowledge is essential. Addressing these aspects will ensure that AI contributes positively to the advancement of human knowledge and social development, respecting fundamental ethical values and promoting a sustainable and equitable knowledge ecosystem.

DiscussionThe evolution of knowledge has been addressed from various perspectives in this study, converging on the noosphere and the potential transformative role of artificial intelligence in the expansion and deepening of human knowledge. In this context, how can humanity adapt to benefit from this technology?

From Georgescu-Roegen's perspective, knowledge evolves through increasingly complex mechanisms of information storage and transmission. Their vision anticipates a transition to electronic systems that store and process knowledge more efficiently than humans do and predicts the crucial role of AI in managing and classifying large volumes of data.

From Varela's perspective, the evolution of knowledge has been possible owing to autopoiesis, enaction and plasticity of the cognitive system of the human being due to the interaction with the environment and its ability to adapt to change. AI can accelerate their evolutionary phase and facilitate greater integration and complexity in the interaction of cognitive systems with their environment, generating additional forms of interaction to those currently present.

AI can accelerate the existence of the noosphere, although this new state of knowledge can evolve with or without AI. However, if AI becomes its catalyst and mediating agent of this new space, this situation may redefine the mechanisms and structures through which human knowledge is expanded and democratized, not only expanding access to knowledge but also redefining the dynamics of collaboration and innovation. In this case, human beings will benefit to the extent that there is universal access and that there is the possibility of collaborating in their development.

Dwivedi et al. (2021) and Gill et al. (2022) emphasized AI's transformative potential across various sectors, particularly in areas such as health care, finance, and education, where AI-driven systems optimize decision-making and improve efficiency. This study aligns with these perspectives, particularly with respect to the role of AI in accelerating knowledge generation and fostering global collaboration. However, it expands upon these findings by positioning AI not only as a tool for operational improvement but also as a fundamental mediator in the evolution of human knowledge itself, exemplified by the concept of the noosphere.

This study introduces a unique theoretical framework in which AI serves as a catalyst for collective intelligence, suggesting that the influence of AI extends beyond individual industries to reshape the mechanisms by which knowledge is generated and shared. This is a great challenge for the business environment, which will have to adapt current business models, many of them focused on the intellectual property of technological developments, and because these new technologies require broad access to knowledge and continuous collaboration of knowledge, new models must emerge in which intellectual property is balanced with open innovation and shared knowledge.

Businesses need to rethink traditional profit structures that rely heavily on proprietary technology and shift toward models that emphasize collaborative innovation, cocreation, and shared intellectual resources. New models must emerge in which companies focus on fostering partnerships, leveraging AI-driven knowledge networks, and creating ecosystems where knowledge flows freely among stakeholders while still allowing for monetization through services, customization, or data-driven insights. This collaborative approach will enable businesses to remain competitive while contributing to the broader democratization of knowledge, ensuring that advancements in AI and the noosphere benefit society as a whole.

On the other hand, research raises critical concerns regarding the ethical, social, and cognitive implications of AI integration. This includes addressing biases in AI algorithms, ensuring transparency in AI decision-making processes, and considering the broader social and economic impacts of integrating AI into industries and professions (Bostrom & Yudkowsky, 2018). The ethical dimension also extends to the responsibility of AI creators and users to prevent harm and promote beneficial outcomes for all of society (Heilinger, 2022; Prem, 2023).

In addition to these concerns, there is the issue of global cooperation in AI governance. Legal and governance frameworks can slow the evolution of AI. The development and use of AI are not confined to any single nation or entity; international collaboration is essential for establishing global norms and regulations (Dafoe, 2018). This requires a collective effort to understand and manage the potential risks and benefits of AI, transcending individual interests for the greater good of humanity.

Moreover, we face the danger of humanity becoming overly reliant on AI, potentially leading to a gradual loss of cognitive capacity due to the reduced use of skills developed over time, such as language, writing, and reflective thinking. The risk of becoming less intelligent due to the diminished use of our cognitive abilities is a real concern (Nyholm, 2024). Varela's (1991) work on cognitive plasticity and autopoiesis warns of the risks associated with overreliance on AI, particularly in undermining human cognitive autonomy and creativity.

The loss of meaning that humans may encounter as AI takes over significant tasks traditionally performed by people also presents a challenge. This shift may create a meaning gap, compelling humans to seek new tasks that provide purpose to their lives (Nyholm & Rüther, 2023).

While this study acknowledges these risks, it diverges by advocating for the coevolution of human intelligence and AI, where humans are required to develop new cognitive skills to thrive in an AI-mediated knowledge environment. Furthermore, scholars such as Nordström (2022) highlight the uncertainties surrounding the long-term impact of AI on knowledge creation and societal structures.

There is also the dilemma of the loss of autonomy for people with free will who are able to freely choose their destiny, whether good or bad, and that, in the empire of the AI, this creature begins to decide for him. This situation can be extended to society, where the AI currently chooses what is best for society in a kind of large brother who is able to decide what is best for society. At a final extreme, AI determines the destinies of humanity in terms of its progress and development (Sadin, 2015, 2018; Thinyane & Sassetti, 2020).

The first risk can be approached with several strategies; for example, it is crucial to develop comprehensive educational programs aimed at enhancing cognitive skills and digital literacy from an early age to interact with AI, a field of incipient development (Celik, 2023). These programs should focus on going beyond the simple transmission of content to develop the capacity for flexibility, learn to change, and cultivate the capacity for flexibility; in this sense, Varela suggests that we can learn a lot from the organization of the brain, which is both a generalist and a specialist, and it controls and executes. Moreover, it plans, pilots, regulates, evaluates, hypothesizes, imagines and invents. The secret of the brain is above all its immense capacity for connectivity (Keven Poulin, 2015).

As Varela mentions,

“It is precisely the surplus of labor that will allow it to function in a probabilistic way and escape the determinism in which it risks locking itself up owing to lack of flexibility. Neural functioning gives us the example of a behavior that privileges initiative over passivity, open-mindedness over narrowness, collaboration over competition, flexibility over rigidity, autonomy over dependence, questioning over authoritarian belief” (Keven Poulin, 2015).

However, there is still a long way to go to generate new ways to improve cognitive skills, including the transformation of the current educational model that has not changed in centuries (as well as the scientific method as a way of understanding science), which encourages the transfer of content to a holistic learning framework, where reasoning is stimulated, analysis and criticism through education that emphasizes flexibility and adaptability (plasticity) over the mere acquisition of content to improve our ability to understand and generate knowledge.

The development of user-friendly AI collaboration tools that enhance human capabilities rather than replace them is another critical strategy. These tools should be designed to be intuitive and accessible, allowing individuals to leverage AI without requiring advanced technical knowledge (Kelly et al., 2023). By fostering an environment where humans and AI can cooperate and work together seamlessly, we can increase productivity and creativity across various domains (Li et al., 2022).

The second risk requires robust ethical and regulatory frameworks; for example, establishing strict ethical guidelines and transparency requirements for AI development is crucial. Oversight bodies should be created to monitor AI activities and ensure that they align with the interests and common good of humanity. Regular audits and public reporting on AI initiatives can help maintain transparency and accountability in AI development and deployment.

The implicationsHuman knowledge has undergone significant changes on the path that humanity has traveled, and we can assume that it will continue to evolve. However, from our perspective, AI can accelerate this process, and, as explored in this study, this situation can have profound implications for multiple dimensions of society.

The establishment of sophisticated collective intelligence can transform the way we generate knowledge and how we use it and potentially reshape the way societies value and relate to intellectual resources and the way they solve their problems locally and globally. It can transform education to the extent that cognitive skills must be generated in the human being to interact with this new mediating agent and the need for cognitive development for adaptability and critical thinking.

In the business world, a globally connected knowledge-based environment presents challenges, particularly with respect to intellectual property-based business models, new dynamics of organization and use of the labor factor, and the need to empower businesses to adapt to a knowledge-driven economy. On the other hand, new rules and regulations will be required that allow companies to participate in open innovation, where companies and researchers can exchange ideas and develop solutions more quickly and efficiently, consolidating a deeply interconnected economic ecosystem dependent on the continuous flow of shared information and knowledge beyond licenses and intellectual property.

Currently, the integration of AI into production and business management systems makes it possible to improve operational efficiency and significantly improve decision-making processes by identifying trends and optimizing resource allocation, creating a more resilient and agile infrastructure. However, with the establishment of the noosphere, the business objectives and paradigms that companies currently follow may change, where the rules of allocation and decision-making of economists (profit maximization, cost minimization, productive efficiency) will intersect with other interests at the level of the human species, such as the conservation of species and the biosphere. A better understanding of the effects of human activities (economic and production) on the environment (social, biosphere) is needed to solve the problems that now afflict us, such as pollution, solid waste and inequality.

However, the scenario of the evolution of human knowledge can be posed without the occurrence of the singularity of AI. In this case, evolution would follow a trajectory based on human cognitive capacities, progressive technological advances, and social and educational structures, where knowledge would continue to expand cumulatively. That is, advances in science and technology depend on the pace of human discovery and innovation, supported by computational tools but not radically transformed by them. This could imply a slower pace of progress and greater dependence on interactions between generations of researchers.

Technology still plays a crucial role, but AI tools are limited to advanced research support systems, such as automating complex processes or synthesizing large volumes of information. Without singularity, AI cannot generate new knowledge autonomously, so creativity and human reasoning continue to be the main sources of innovation. The evolution of knowledge is subject to the limitations inherent in human cognition, such as the ability to process complex information, epistemological barriers, and cognitive biases. Although assisted by technology, human intelligence remains the center of scientific progress.

Gaps in the ability to produce and access information continue to be pronounced, with academic institutions and research centers with greater resources continuing to dominate knowledge production, exacerbating global inequalities. The evolution of knowledge continues to depend heavily on formal education and public policies that promote research.

Future research directionsThe rapid advancement of artificial intelligence and its integration into human knowledge systems, as explored in this study, opens several key avenues for future research. First, empirical studies are needed to validate the theoretical frameworks surrounding the noosphere and the role of AI in accelerating knowledge evolution. These studies could focus on real-world applications of AI in education, business, and scientific research, examining how AI-mediated knowledge networks influence collaboration, problem solving, and innovation across disciplines.

Second, future research should explore the social and cognitive impacts of AI on human adaptation. Specifically, there is a need to investigate how individuals and organizations can best develop the necessary cognitive and digital skills to interact with AI-driven systems. This includes assessing the effectiveness of educational models that incorporate AI-based learning tools and personalized educational platforms, as well as identifying best practices for reskilling the workforce to thrive in AI-centric environments.

Third, the ethical, legal, and governance challenges associated with integrating AI into knowledge management and its generation should be further explored. Property rights are an imperfect way to protect knowledge; however, how we protect against the misuse of knowledge; what problems we solve or prioritize solving; and how the complexity of these phenomena challenges AI experts, ethicists, policy-makers, and educators are crucial for creating governance models that ensure that the development of AI in the business environment is aligned with social values and the common good.

Future studies should examine the long-term impact of AI on knowledge creation and dissemination, particularly how AI can shape global knowledge networks, innovation processes, and cultural exchange, and explore how humans can adapt their cognitive abilities to maintain agency within an AI-dominated noosphere. This critical examination of the literature underscores the need for continued interdisciplinary dialog to refine our understanding of AI's broader implications for both human knowledge and social structures.

We emphasize the potential benefits of human-AI collaboration but do not delve deeply into the nuances of these interactions. The dynamics of human‒AI interactions, including user acceptance, trust, and the psychological impact of working with AI, are complex and require further exploration. Future research should include user studies and experimental designs to better understand these dynamics. This study provides a broad overview but cannot address all possible ethical dilemmas and legal issues in detail. The development and implementation of ethical and legal frameworks for AI require interdisciplinary collaboration and continuous refinement, and we highly believe in a global joint vision that integrates the necessary safeguards that protect the knowledge of humanity, a diverse and complex species.

Limitations of the studyDespite the valuable insights provided by this study on the role of artificial intelligence in the evolution of human knowledge and the formation of the noosphere, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the research is primarily theoretical in nature and relies on conceptual frameworks rather than empirical validation. While the study offers a comprehensive exploration of AI's potential to accelerate knowledge creation and dissemination, the lack of practical case studies or real-world data limits the immediate applicability of its findings. Future research should incorporate empirical studies to test and refine the proposed models in diverse contexts and industries.

Second, the study's broad scope, which covers the technological, ethical, and social dimensions of AI integration, restricts the depth with which each topic can be explored. For example, the ethical implications of AI—particularly issues related to privacy, bias, and governance—are discussed at a high level, but the study does not delve deeply into specific legal frameworks or regulatory mechanisms required to address these challenges. Additionally, the analysis of cognitive and educational impacts lacks a detailed consideration of how different educational systems and cultural contexts may influence the adoption and effectiveness of AI-driven learning platforms.

Finally, the rapidly evolving nature of AI technology presents a challenge to the longevity of the conclusions of studies. AI advancements may outpace current theoretical frameworks, necessitating continuous updates to keep the analysis relevant. Moreover, the global variability in AI adoption and the uneven distribution of technological infrastructure across regions mean that the findings may not be universally applicable, particularly in contexts where access to AI and digital resources is limited. Addressing these limitations in future research will be critical to ensuring a more comprehensive understanding of AI's role in shaping human knowledge and society.

ConclusionsThe manuscript examines how artificial intelligence can drive human understanding, arguing that it is a critical catalyst for a new phase in the evolution of human thought and the construction of sophisticated collective intelligence. This study explores the evolution of knowledge through the lens of the noosphere and the transformative potential of AI. This discussion has revealed several key insights into the roles and implications of AI in this evolutionary process.

First, AI has the potential to accelerate the evolution of knowledge, and it has the potential to mediate the process of generating individual knowledge and generating a space of general knowledge, which could make the concept of the noosphere a reality.

Second, AI can significantly accelerate the evolutionary phase of knowledge, although we must be aware that this new phase of knowledge evolution can occur with or without AI. The fact that AI can mediate access, use, generation and diffusion of knowledge poses risks that must be considered, such as the possibility that humanity will be marginalized or participate marginally in the generation of knowledge and poses new challenges in terms of the need to continue developing our cognitive capacities and flexibility for change, to adapt to interact in this new space of collective knowledge and to interact with machines, which will require new skills and ways of learning that have not existed until now.

Third, the concept of the noosphere, as proposed by Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, envisions a higher state of consciousness and knowledge emerging from the collective construction of human knowledge. In this context, AI acts as a mediator, expanding access to knowledge and redefining the dynamics of collaboration and innovation. The ability of AI to integrate and democratize knowledge helps overcome geographical and socioeconomic barriers, fostering global connectivity and collaboration.

In analyzing the impact and potential of artificial intelligence as a mediator in the evolution of the noosphere, AI has emerged as an indispensable catalyst for the expansion and deepening of the noosphere because of its unprecedented ability to process and analyze vast amounts of data. This capability not only enriches human understanding with deeper insights into complex patterns across various disciplines but also uncovers connections and knowledge previously unexplored, marking a significant evolution in the management and application of collective knowledge.

In the field of business, an economic environment based on knowledge and the integration of advanced technologies, such as artificial intelligence, presents both opportunities and challenges for companies in the short and long term, moving from greater operational efficiency and more agile decision-making to the need to reformulate business models and intellectual property systems; as the notion of the noosphere consolidates, it is likely that traditional business objectives, and the paradigms that drive them, will change as AI transforms the productive organization and there are new ways of generating and using human knowledge to generate economic value.

Human knowledge will evolve with or without the intervention of AI, but AI in the generation of knowledge poses new challenges, whether AI is a tool that enhances human cognitive abilities or whether, once singularity occurs, it is transformed into an entity with cognitive abilities equal to or superior to those of human beings. The first of these is the need to develop new cognitive skills to interact given sophisticated collective intelligence. The second is related to the governance and control capacities that humanity will have to develop to subordinate knowledge to the benefit of humanity and mitigate all the risks related to an AI that mediates this new space.

CRediT authorship contribution statementCristian Colther: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Jean Pierre Doussoulin: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

The authors would like to acknowledge the comments of the anonymous referees and, in particular, the discussion and enrichment of the emerging theory of sophisticated collective intelligence, its risks, limits and scope, which will be the basis for future avenues of research.