A wide range of public and private organizations, businesses and individuals throughout the world are experimenting with web-based, GIS, virtual and mobile technologies, often in collaboration with each other in order to develop civic technologies. Online communities form the basis for civic platforms, which are incubators for new ideas through peer-to-peer networks, stakeholder mobilization and collaborative and partnership engagement. Digital data analytics offers unprecedented opportunities to build capacity within communities simply because online platforms serve as acquisition hubs of structured and unstructured data. Notwithstanding, technology powered forms of engagement face multiple design and management challenges. Currently, limited research is being conducted into the online community using digital data analytics in non-business contexts. This explorative study further develops existing knowledge on civic tech communities and the use of digital data analytics. To this end, we review the previous research in order to understand how to aggregate literature on online communities, civic technologies and data analytics into a conceptual model that is useable by both academics and practitioners. The framework proposed serves as the first step in differentiating the building blocks of relevant digital data in managing civic technology communities and should be regarded as an effort to structure the available sources. Thus, the focus of the proposed conceptual model is not to offer prescriptive guidelines on the use of digital analytics, but rather to present a broader understanding of the emerging phenomenon and dimensions of data analysis.

Throughout the world, numerous public and private organizations, businesses and individuals in society are collaborating with each other in their use of web-based, GIS, virtual and mobile technologies. These so-called platforms include, among others: tools that report specific issues (e.g., FixMyStreet), ideation platforms (e.g., OpenIDEO), transparency projects (e.g., PromiseTracker), legislation engagement platforms (e.g., GovTrack, TheyWorkForUs), mapping platforms (e.g., Ushahidi, Mapbox), data crowdsourcing (e.g., LocalData, Zooniverse). The growth of online communities using ‘civic technologies’ (or ‘civic tech’) is rapid and in the year 2013 attracted more than $431 million in investment monies (Knight Foundation, 2013). Online communities form the basis for such civic platforms and act as sources for new ideas through peer-to-peer networks, stakeholder mobilization and collaborative activities. Yet, despite the increase in funding, investment and activity, few civic tech platforms have been able to scale their work and build communities that are resilient and self-sustaining (Knight Foundation & Rita Allen Foundation, 2017).

The Internet and new media offer novel opportunities to form online communities (networks) that can help to address social issues. Indeed, such communities play an increasingly important role in our society, manifesting ‘high problem-solving capabilities’ (Luo, Xia, Yoshida, & Wang, 2009) and ‘higher-order intelligence, solutions and innovation’ (Lykourentzou, Vergados, Kapetanios, & Loumos, 2011). Henry Jenkins has argued that online communities might be regarded as the ‘bowling alleys’ of the twenty-first-century, connecting youth and serving as starting points for civic activities (Jenkins, 2009). Online communities can facilitate social change by enhancing learning and behavioural changes, mobilizing movements and amplifying voices (Hong & Page, 2004; Krause, Ruxton, & Krause, 2010). However, numerous design and management challenges are apparent (Gibson, Cantijoch, & Galandini, 2014; Kraut et al., 2012; Lutz, 2015; Peixoto & Fox, 2016; Shueh, 2016). For example, the diversity created by mass participation offers huge potential for collective intelligence to emerge, yet this is currently limited (Bonabeau, 2009; Erickson, Petrick, & Trauth, 2012; Malone, Laubacher, & Dellarocas, 2010; Woolley, Chabris, Pentland, Hashmi, & Malone, 2010). Significant limitations include: the capacity to grow a base of diverse and active users (Bakshy, Rosenn, Marlow, & Adamic, 2012; Cunha, Jurgens, Tan, & Romero, 2019; Cheng, Adamic, Dow, Kleinberg, & Leskovec, 2014; Kairam, Wang, & Leskovec, 2012; Tan, 2018), retaining users (Danescu-Niculescu-Mizil, West, Jurafsky, Leskovec, & Potts, 2013; Jurgens, McCorriston, & Ruths, 2017; Tan & Lee, 2015) and provide services sustaining active involvement (Kairam et al., 2012; Zhu, Kraut, & Kittur, 2014).

Digital data analytics offer unprecedented opportunities to build capacity in online communities since the platforms serve as acquisition hubs for structured and unstructured data. There is ongoing research on the use of data analytics in online communities seeking social change, although the focus is largely on communities formed through traditional social networking sites such as Facebook or Twitter (e.g., Bonsón, Torres, & Royo, 2012; Hou & Lampe, 2015; Lidén & Nygren, 2013; Nah & Saxton, 2012; Mergel, 2013). Yet, the problems civic tech communities face in attracting new members and maintaining existing ones, differ because they are not a constant in the life of the user. This article provides researchers, designers and practitioners with a useful starting point that will enable to form a more complete understanding of current thinking expressed in the academic literature, as well as opportunities to build the capacity of civic tech communities through digital data analytics. By proposing a conceptual model that redefines the capacities of civic tech communities and areas for the application of data analytics, this article further develops knowledge on the aforementioned communities.

With this in mind, the research proceeded as follows. First, we explored the use of digital analytics in online communities seeking social change through a literature analysis. Second, we defined the elements and capacities of civic tech communities through the analysis of conceptual relatives and a systematic review of current research efforts. Lastly, we designed a conceptual model that is able to reliably provide us with a comprehensive understanding of how data analytics can help the civic tech communities achieve their goals, connect with the audience and employ more effective methods of communication.

Digital data analytics and online communitiesInformation and communication technologies (ICT) offer new forms of data and stimulate the development of new techniques for the analysis of social processes (Housley et al., 2014). Data-driven approaches already firmly established in the private sector are increasingly applied in organizations seeking social change in decision-making, performance tracking and information management (Bopp, Harmon, & Voida, 2017; Stoll, Edwards, & Mynatt, 2010; Voida, 2011). The United Nations has noted the role of big data in social change in a report that asserts that ‘the new sources of data, new technologies and new analytical approaches, if applied responsibly, can enable more agile, efficient and evidence-based decision-making and can better measure progress’ (United Nations, 2015).

The application of data analytics to effect social change allows us to obtain insights that form the basis for future action through collaborative data collection and analysis. There are many benefits and examples of crowdsourced data collection include: Ushadidi, a non-profit tech company specializing in the development of free and open-source software for information collection, visualization and interactive mapping; as well Poplus SayIt, which is an open government initiative focusing on the innovative use of big government data sets. Collaborative analytics employ similar back-end tools as those used in the business sector to address social challenges. For example, DataKind pairs data scientists with civil society groups in a pro-bono capacity. The most prominent example is the collaboration with the American Red Cross in identifying counties that would benefit from smoke alarm installation campaigns (Williams, 2016). Another benefit is the use of analytics in capacity development of online communities. Online platforms allow us to track user behaviour and understand how a community is formed and maintained online. Using such data, managers of the tools can actively engage in community development and address community issues (Gruzd & Haythornthwaite, 2013).

The volume of data accumulated through online media outlets pose several methodological challenges (Housley et al., 2014). Whilst the variety of platforms and technological solutions available for hosting communities is growing, it is increasingly difficult to obtain metrics that can be applied in different civic communities. The depth of technologies used in managing and hosting communities differs in various research studies. In this regard, the research in this field is somewhat ‘blurred’, such that the research for this article used the spectrum proposed by Stempeck (2016) on the depth of technologies in communities with civic goals. Here, the author suggests three levels – civic feature, civic externalities and civic product. The civic feature refers to the insertion of a civic engagement perspective into mainstream media technologies (e.g., search engine informs the user about the election candidates). Civic externalities refer to the ICTs designed with either zero or limited intent to affect civic life, however the broad reach still influenced society (e.g., Twitter and Facebook allow broader inclusion, transparency and conversations). Civic products are platforms specifically designed to achieve social change (reporting platforms, mobile applications, etc.).

The research on the use of data analytics in online communities seeking social change is active but mostly focused on communities formed through existing platforms and traditional social networking. In this regard, research tends to focus on a number of factors, including: the analysis of ‘sentiment’ (Bonsón et al., 2012; Lidén & Nygren, 2013), social media effectiveness (Hou & Lampe, 2015; Khan, 2015; Mergel, 2013; Nah & Saxton, 2012,), storytelling with data (Choi, 2017; Erete, Ryou, Smith, Fassett, & Duda, 2016), benefits of open data (Alexander, Brudney, Yang, LeRoux, & Wright, 2010; Lakomaa & Kallberg, 2013), data literacy (Data-Pop Alliance, 2015), individual networks like Weibo (Huang, 2019), Twitter (Bollen, Pepe, & Mao, 2009; Bruns & Stieglitz, 2012; Mislove, Lehmann, & Ahn, 2011; Pak & Paroubek, 2010; Thelwall, Buckley, & Paltoglou, 2011; Williams, Edwards, & Housley, 2013) and Facebook (Farzan, Dabbish, Kraut, & Postmes, 2011; Kim & Hastak, 2018; Paton & Irons, 2016).

Stand-alone civic products (described in the following section), confront many problems in trying to attract new members and maintain existing ones and these differ widely because they are not constantly present in the user’s life. One scholar who concurs with this view is Mutemeri (2017) who suggests that organizations find it difficult to study their behaviour in the absence of suitable evaluation frameworks. Moreover, Cunha et al. (2019) suggest non-profit communities often lack the technical, financial and time resources to fully utilize available data. The Knight Foundation & Rita Allen Foundation (2017) also sound a warning; since ‘companies such as Facebook, Google and Snapchat continue to integrate tech features into their platforms’, civic products are urged to discern their business viability. Despite the activity very few platforms in the space have been able to sustain and scale their work. To fill this gap, online communities employing civic products will be discussed in the next section by analysing the emerging field of civic technologies and identified core issues for data analytics.

Defining the capacities of civic technology communitiesThe term ‘civic technologies’ is used to define civic products – mobile and web platforms designed specifically to achieve social change. Quite a number of NGOs, active citizens and socially-minded businesses throughout the world are developing digital tools that can be used to increase government transparency, efficiency and improve the lives of communities in which they are involved (Rumbul, 2015). The practitioner community mostly uses the term, although its popularity continues to grow in the academic community (Clarke, 2014; Rumbul, 2016; Shaw, 2015; Sifry, 2014; Verhulst, 2015). The so-called ‘civic tech movement’ was inspired both by President Obama’s 2009 directive to put the US government data online and the efforts by the individuals and loosely constituted groups with particular digital expertise who wanted to see faster change in solving complex global social and governance problems (Rumbul, 2015). Hou (2018), p. 14) states that ‘unlike e-government systems that make existing public services more accessible, efficient and convenient, civic technologies aim to enhance the democratic capacity of governance and public organizations by encouraging more public engagement and citizen participation’. The field, however, lacks a cohesive definition and there are major differences in the way the practitioners and the academic community define civic technologies. This has engendered unnecessary confusion because several definitions describe identical processes. In this section, we take a closer look at the conceptual relatives of civic technologies and current research efforts in defining the term to clarify the main building blocks of civic tech.

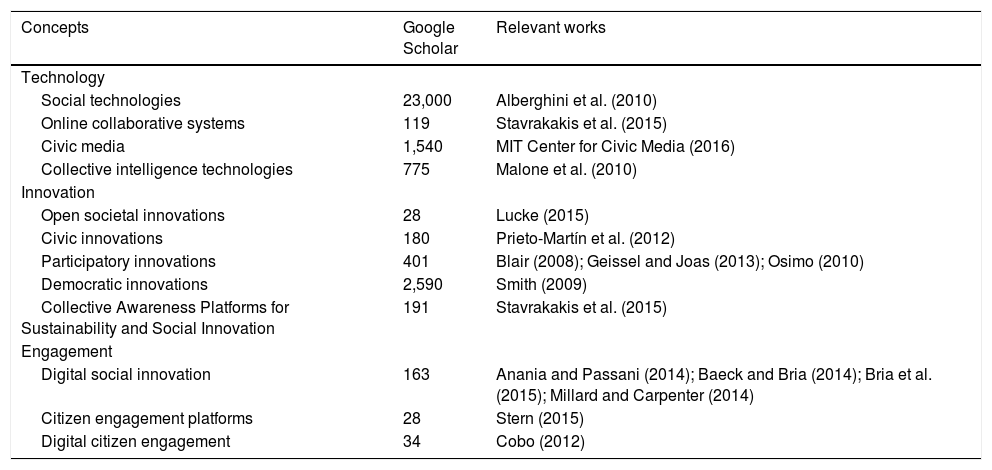

The use of ICT in building communities for social change has been defined from multiple viewpoints and new definitions are still being formulated. Different researchers apply different labels although they tend to converge towards the same meaning. Research for this paper identified these definitions through a literature review, with a particular focus on research into civic action for social change through digital means. The Google Scholar database was used to evaluate the diffusion of the term within the research community. Fieldwork conducted in the 3rd quarter of 2016 applied exact match strategy (e.g., ‘civic media’, ‘participatory innovations’). To obtain the most current and relevant results, articles and other research items published before 2000 were ignored. The variety of the labels and underlying concepts revealed three main tendencies expressed as clusters – technology, innovation, engagement – which were established based on the primary focus of the concept (see Table 1).

The conceptual alternates of civic technologies.

| Concepts | Google Scholar | Relevant works |

|---|---|---|

| Technology | ||

| Social technologies | 23,000 | Alberghini et al. (2010) |

| Online collaborative systems | 119 | Stavrakakis et al. (2015) |

| Civic media | 1,540 | MIT Center for Civic Media (2016) |

| Collective intelligence technologies | 775 | Malone et al. (2010) |

| Innovation | ||

| Open societal innovations | 28 | Lucke (2015) |

| Civic innovations | 180 | Prieto-Martín et al. (2012) |

| Participatory innovations | 401 | Blair (2008); Geissel and Joas (2013); Osimo (2010) |

| Democratic innovations | 2,590 | Smith (2009) |

| Collective Awareness Platforms for Sustainability and Social Innovation | 191 | Stavrakakis et al. (2015) |

| Engagement | ||

| Digital social innovation | 163 | Anania and Passani (2014); Baeck and Bria (2014); Bria et al. (2015); Millard and Carpenter (2014) |

| Citizen engagement platforms | 28 | Stern (2015) |

| Digital citizen engagement | 34 | Cobo (2012) |

In the technology cluster the focus is the use of ICT in facilitating collaborative outcomes in groups of individuals. Social technologies refer to any technological solution – social hardware, social software and social media – allowing collaborative action, incidentally the most used term (Alberghini, Cricelli, & Grimaldi, 2010). Less used terms include online collaborative systems, collective intelligence technologies and civic media. Online collaborative systems refer to action-oriented, geographically dispersed teams of individuals working together (Stavrakakis et al., 2015). Collective intelligence technologies enable groups of individuals to do things that seem intelligent collectively (Malone et al., 2010). Civic media is a term coined by researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to define the platforms enabling engagement of communities within and beyond the people, places and problems of their community (MIT Center for Civic Media, 2016).

Innovation cluster refers to the innovative use of ICT tools in solving societal problems. It involves both online and offline modes of engagement. Open societal innovation refers to the utilization (by state and society) of open innovation approaches used in business (Lucke, 2015). Civic innovations refer to new ideas, technologies or methodologies that challenge the existing civic processes and systems (Prieto-Martín, de Marcos, & Martínez, 2012). Participatory innovations are regarded as supplements to representative democracy (Blair, 2008; Geissel & Joas, 2013; Osimo, 2010). Democratic innovations focus on redesigning the institutions that increase and deepen citizen participation in the political decision-making process (Smith, 2009). Collective Awareness Platforms for Sustainability and Social Innovation refer to online platforms creating awareness of sustainability problems and offering collaborative solutions based on networks of people, of ideas, of sensors, enabling new forms of social innovation (Stavrakakis et al., 2015).

Engagement cluster is the least represented by the variety of abovementioned concepts and focuses on citizens and communities, although it excludes other stakeholders in society (i.e., NGO, business, public organizations). Digital social innovation refers to innovative efforts by users, communities and innovators working together in creating collaborative knowledge and solutions for societal problems by employing technological solutions (Anania & Passani, 2014; Baeck & Bria, 2014; Bria, NESTA, The Waag Society, ESADE, IRI, & & FutureEverything, 2015; Millard & Carpenter, 2014). Citizen engagement platforms offer collaborative experience by facilitating online communities (Stern, 2015). Citizen engagement technologies are mentioned several times in Google Scholar results. However, the scientific literature makes no mention of definitions, merely references to the concept. Digital citizen engagement refers to the use of new media technologies in the creation and facilitation of civic, governmental and/or business interactions (Cobo, 2012).

The classification does not imply that other dimensions are absent in defining the terms; rather it identifies the core object of analysis. The results of the Google Scholar review show that those concepts which take broader tools for achieving social goals into account are more popular, yet no term across the disciplines is dominant. The meta-analysis also revealed the complexity of the field and provided the first overview of tendencies as to how issues of civic tech are interpreted in various research fields.

In defining common conceptual elements, the review of civic tech conceptualizations currently used by academics and practitioners has been conducted. Analysts at Microsoft Corporation offer the broadest definition and refer to the civic technologies as ‘the use of technology for the public good’ (Stempeck, 2016, p. 3). According to the Stempeck (2016), the definition is intentionally broad because it should be used as an umbrella term for all the instances where digital tools are leveraged to benefit the public. The Knight Foundation takes a broad approach and in 2015 conducted a civic tech landscape and investment analysis that was the first of its kind, with their resulting definition focussing on the convergence of fields such as collaborative consumption, crowdfunding, government data, community organizing and social networks.

It is important to note that the focus of civic technology definitions tends to differ based on the stakeholder group providing it (Shaw, 2015). Civic society groups, NGOs and practitioners define the concept through the change in the power balance between citizens and governments. For example, Code for America refers to technologies to empower citizens and improve government operations (Code for America, 2017). Similarly, MySociety focuses on the exercise of power over institutions and decision-makers by the civil society (MySociety, 2017). The private sector, meanwhile, defines civic tech communities through the notion of the public sector services by claiming they can help governmental entities to engage with citizens and improve services (Clarke, 2014). Shaw (2015), p.2) suggests that the range of definitions ‘reflect the fact that the sector mixes players with different structures and motivations.’ Formerly distinct stakeholder groups – public organizations (local governments & municipalities, national government entities, cross-national government organizations, EU governing structures, educational organizations, libraries, institutes), private organizations (tech developers, media, private innovation funds, large corporations, SME’s, start-up community) and civil society (NGOs, civic hackers, civic organizations, civic movements, communities, individuals) – can meet and achieve profound social change under the civic tech paradigm.

Following a discussion of the conceptual relatives of civic technologies and a review of current definitions in the academic and practice-based literature, the following key conceptual components of the term were identified: (1) collaboration; (2) information; (3) technology; and (4) social change. Collaboration refers to various types of interactions between different groups in society (i.e., government, citizens, business, NGOs). Information relates to the collection, distribution and analysis of data (i.e., open government data, crowdsourcing, collaborative mapping). Technology refers to digital and interactive tools. Social change is linked to the problems in the society which civic tech is addressing. In essence, civic technologies imply that government cannot do everything themselves and civic society fills in the gaps by co-creating social change.

The capacities of civic tech communitiesSimmons, Reynolds, and Swinburn (2011) suggest that community capacity building like other broad concepts is difficult to capture, has many interpretations and is highly dependent on context. In the broadest sense, community capacity building refers to the development of a set of attributes that enable a community to define, assess and act on issues they consider to be important (Chaskin, 2001). Liberato, Brimblecombe, Ritchie, Ferguson, and Coveney (2011) evaluated the literature on the capacities of communities, identifying nine domains for evaluation: ‘learning opportunities and skills development’; ‘resource mobilization’; ‘partnership/linkages/networking’; ‘leadership’; ‘participatory decision-making’; ‘assets-based approach’; ‘sense of community’; ‘communication’; and ‘development pathway’. The capacities of online communities, however, might involve other dimensions, since communications is conducted through the online medium. This section aims to define capacity building in the context of civic technologies, by analysing the outcomes of the communities as represented in the research literature.

Sifry (2014) offers seven attributes of civic technology and the variety of processes and tools it encompasses: (1) involves citizens in the policy process, (2) involves citizens/beneficiaries in monitoring service delivery, (3) relies on structured information to inform decisions, (4) leverages technology, (5) makes previously hidden, inaccessible, or opaque information more public, (6) empowers citizens/beneficiaries to better hold service providers to account and (7) democratizes previously élite processes. Civic tech platforms do not necessarily include all the mentioned attributes; however, the combination of the attributes provides grounds for classification of this complex field. The variety of characteristics is necessary because civic tech differs by their user groups. Some tools appeal only to a niche group (community of neighbours, a certain city district) while others aim to be fully transformative on a worldwide scale (e.g., MyVoice.co.uk with their continuous work and research on citizen engagement).

Another taxonomy was suggested by the Knight Foundation (2013), which used two themes to distinguish a variety of civic tech tools available. The first theme – open government – identifies projects focused on the transparency of public entities, the accessibility of government data and civic involvement in democratic processes. Second, the community action theme indicates the projects utilizing peer-to-peer information sharing, civic crowdfunding and collaboration to report, identify, debate and/or solve civic issues (Knight Foundation, 2013). Verhulst (2015) expands the classification and offers five overlapping component areas of civic technologies: (1) responsive & efficient city services, (2) open data portals & open government data, (3) engagement platforms for government entities, (4) community-focused organizing services and (5) geo-based services & open mapping data. Dietrich (2015) categorizes civic technologies into three main pillars: (1) transparency & accountability – holding governments to account by making information and processes transparent, (2) citizen-government interaction – making the interaction of citizens with governments easier and more meaningful and (3) digital tools for making citizens’ everyday daily life easier. Sifry (2014) distinguished four segments of civic tech sector: decision influencing organizations, regime-changing entities, citizen empowering organizations and digital government organizations.

The analysis of the typologies of civic tech communities showed that most of them rely heavily on collaborative decision-making and knowledge exchanged through digital technologies. Thus, in the context of civic tech, three capacity dimensions can be discerned: the management of collaborative network which attracts new people and maintains existing community; the management of the generated knowledge (i.e., how the platforms use the information collected and assimilate it); and the management of technologies such as the design and attractiveness of the platform.

A conceptual framework for using digital data analytics in building capacities of civic tech communitiesThis section presents a preliminary conceptual model of building capacities of civic tech communities for the use of digital data analytics. Community capacity building is a term that refers to processes that establish and reinforce the skills, abilities and resources that communities need to survive, adapt and thrive in a fast‐changing world (Philbin, 1996). This means that all communities have inherited strengths, skills and abilities and no single factor alone is able to sway the change towards more inclusive and engaging online communities. Rather, a combination of drivers operates at different levels so that a multi-layered framework is needed to assess civic tech communities, as well as detect the factors leading to higher performance. Conceptual models help to understand the complexity of system processes and demonstrate the links between them (Imenda, 2014).

The work of Castells (1996) in The Rise of the Network Society has been highly influential and it is now commonplace to conceptualize the social, economic and organizational aspects of modern society in terms of networks. The latter implies the ‘flattening’ of power, the dynamic flow of information and oppose traditional social constructs that are usually hierarchical. Luo et al. (2009) applied the network approach to studying online communities by introducing the notion of a knowledge network. Effective knowledge networks share several characteristics (Lettieri, Borga, & Savoldelli, 2004; Luo et al., 2009) – a collaborative community, a diverse set of members and a specific topic of knowledge and organizational processes that ensure meaningful connections. The understanding of online communities as a knowledge network put forward by Lykourentzou et al. (2011) and the elements of civic tech communities identified in previous sections serve as the basis for the conceptual model.

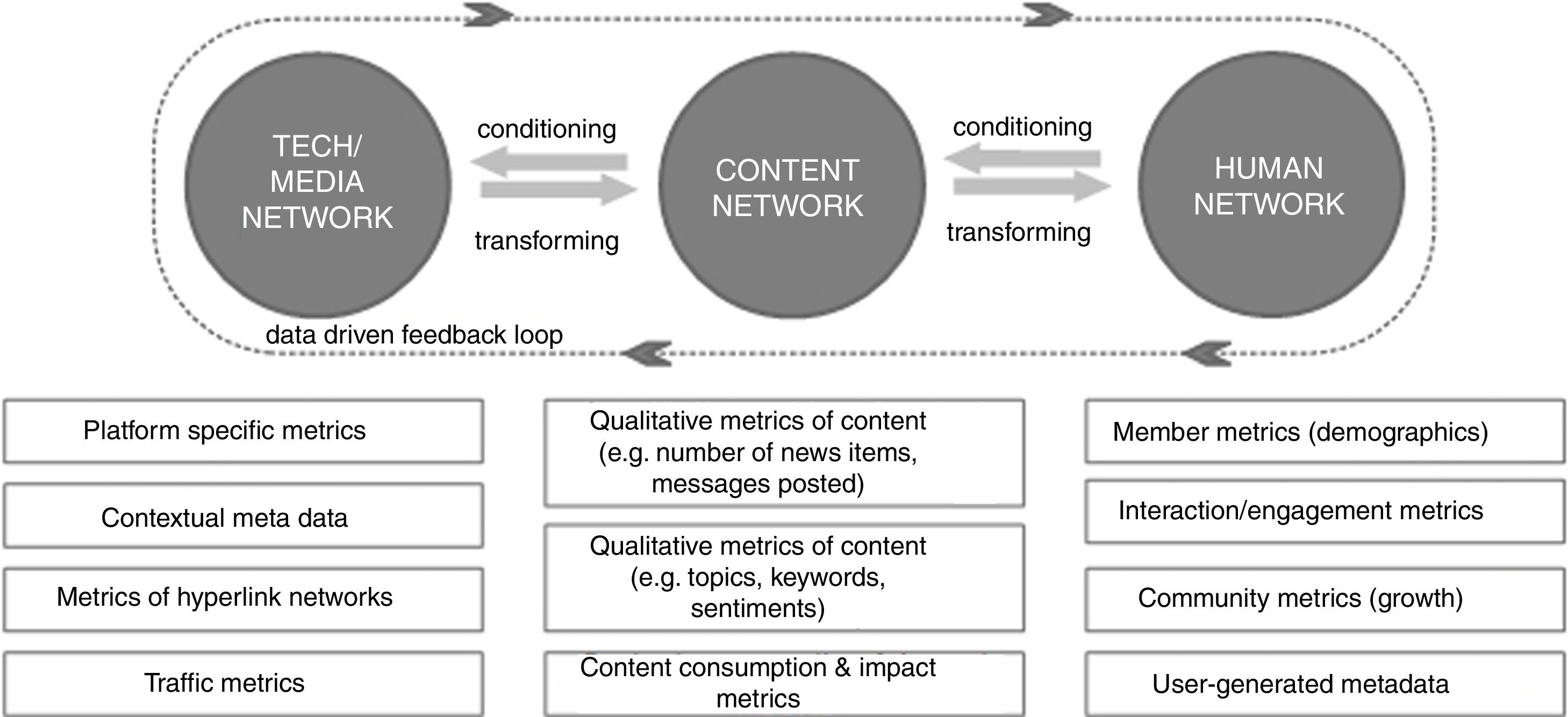

The conceptual framework (see Fig. 1) incorporates three interrelated networks – tech/media, knowledge and the human, which is a combination suggesting that online communities serve as intelligent filters, helping members to deal with growing amounts of information. The model defines the types of data drawn from networks, apps and platforms that could be used to analyse the social and contextual factors shaping community behaviour. The framework proposes a platform for understanding the underlying principles of data analytics in community management. The monitoring of online communities serves several purposes – understanding activities and dynamics, tracking behaviour and influence, studying the impact of technical features, tracking reputation, listening to the opinions of members and extracting ideas.

The technology/media network facilitates knowledge transmission, integration and generation in online communities. Online platforms enable an exchange of information, services, attention between the provider and users, hence the tech network metrics should focus on the performance of technology systems supporting civic tech communities. The sample metrics include, but are not limited to: platform-specific metrics (e.g., system availability, transaction speed, response time, information throughput; contextual metadata) identifying the provenance of the online item; metrics of hyperlink networks (i.e., online social structures represented by hyperlinks analysed through measures of between-ness centrality, degree centrality) and traffic metrics including site visits, average time spent on site, bounce rate, interactions per visit, etc. (Arena & Crystal, 2018).

Another important dimension in the development of the conceptual model is the content network which refers to information generated by the civic tech community. Here, the focus is on leveraging the insights, language and wording in communication between community members and external stakeholders (Network Impact, 2017). The sample metrics include, but are not limited to, quantitative, qualitative and content consumption/impact metrics. Quantitative metrics refers to the mentioned volume of messages, ideas and news items in the community. Qualitative metrics tracks the sentiments of the community and allows us to generate discussion clouds, identify commonly used keywords and understand the frequency and quality of user-generated content. Content consumption and impact metrics refer to measuring the internal and external reach that the content generates. The understanding of semantic networks allows the construction of mental models and cognitive schemas that can explain relationships between members of a community.

The analysis of the human network provides insights into properties related to the collaboration of the stakeholder groups. The member metrics refers to demographic properties of the civic tech community such as characteristics and attributes of community members and segmentation. Interaction metrics provide insights into how members create and share content. Community metrics allows evaluating the health of the community in terms of active users and the time they spend contributing to the activities of the community. User-generated metadata refer to the labels and keywords community members add to the data like images or graphs. Community data analytics promote agile methods of management– knowing the members of the community and their behaviours leads to adaptive capacities and resilience (Network Impact, 2015).

The proposed conceptual model in Fig. 1 is novel because: (a) it supports the civic community managers in data-driven decision-making; and (b) it provides a framework for future research efforts. The proposed conceptual model does not offer prescriptive guidelines on the use of digital analytics, but rather a broader understanding of the emerging phenomenon of civic tech communities and dimensions of data analysis. Obtaining a holistic view of the platform performance (by integrating feedback and external input) helps to identify weaknesses to improve as well as strengths that can be leveraged. Accordingly, the framework does have certain limitations, hence this paper is conceptual and exploratory. What is needed is an empirical examination of the theoretical findings regarding the use of data analytics in civic tech communities. Possible avenues of research include the definition of maturity models which connect the metrics and desirable social change. Also, the definition of complex and emergent socio-technical systems such as civic technology communities, is unavoidably partial, context-specific and temporary.

Conclusions and recommendationsIncreasingly, social scientists are conducting research into the forms, drivers and consequences of online communities. Digital analytics provides a new perspective for us to understand the underlying needs of these communities, as well as opportunities to evaluate the outcomes of collective actions taking place online. The variety of tools and communities is growing, so there is a need to define new frameworks to fit the changing context. However, the specific use of analytics in platforms originating outside traditional social networking sites excites little interest among researchers. Thus, the aim of this research was to develop a theoretically derived framework to conceptualize the dimensions for digital data analytics needed to build capacity in global civic tech communities. To this end, this study has expanded on previous works on online community management, civic technologies and digital data analytics. From this it is proposed that three base networks – tech/media, knowledge and human – operate in the context of civic tech communities. The proposed framework serves as the first exercise in differentiating the building blocks of relevant digital data in managing civic tech communities and can be considered as an effort of structuring the available sources. Such a framework benefits the initiators of virtual communities in evaluating activities within the network, monitoring the progress and making decisions. The need for further empirical research cannot be overstated. A maturity model of the ecosystem could be designed to provide more detailed guidelines for actor involved in how to achieve the value. Additional work is needed to formulate measures and indicators of successful initiatives.