This research aims at analyzing the effects of entrepreneurial orientation (EO) on absorptive capacity (ACAP) and open innovation (OI) in small Colombian businesses, while also determining whether ACAP significantly influences OI. Additionally, it intends to measure the mediating effect of ACAP on the relationship between EO and OI. The study employed a quantitative approach and cross-sectional design, utilizing structural equation modeling. Data was gathered from a sample of 145 business owners in the department of Bogota, Colombia, using a simple random sampling technique and a self-administered questionnaire. The results indicate that EO strongly influences ACAP. Although no direct significant influence on OI was found, a significant indirect effect was observed. Furthermore, EO has a significant total effect on OI. ACAP was shown to significantly influence OI, demonstrating a full mediating effect on the relationship between EO and OI. These findings have important implications for entrepreneurs and decision-makers and contribute to the development of dynamic capabilities theory.

Recently, open innovation has emerged as a crucial capability for achieving competitiveness in a volatile environment (Bogers et al., 2018). Organizations that engage in activities focused on combining resources and capabilities increase their chances of competing with others through more innovative business models (Huber et al., 2020). From the perspective of open innovation, innovation processes are intricately linked to the broader innovation system in which a company operates, enabling it to leverage technological functionalities and knowledge (Remneland-Wikhamn & Wikhamn, 2011). Theoretical discussions emphasize the need to develop capacities that facilitate open innovation, including not only absorptive capacity, which enables the flow of information (X. Zhang, 2017), but also an active value creation process rooted in an innovative and risk-taking approach (Allameh & Khalilakbar, 2018; Su et al., 2020). However, there is a lack of literature that explores the ideal scenario wherein an entrepreneurial posture and knowledge capture processes which consolidate open innovation, thereby strengthening the business environment. Open innovation practices have garnered significant attention in the literature, as evident from the considerable number of academic search results on Google Scholar in 2022, which yielded 48,800 articles on the topic of "open innovation influence". These works demonstrate the importance and relevance of open innovation for researchers and readers alike.

Entrepreneurial orientation has been found to enhance the ability to identify, create, and capitalize on business opportunities (Genc et al., 2019). In the context of developing countries, research has examined how small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) adopt an entrepreneurial stance despite limited resources, aiming to offer competitive products in the market (Zhai et al., 2018) and maximize activities that generate new ideas and higher added value (Jasimuddin & Naqshbandi, 2019). In adverse environments, differentiation activities have emerged as strategic alternatives (de Medeiros et al., 2017). The literature has explored how knowledge and available resources serve as potential elements for developing competitive advantages in innovation (Nobakht et al., 2021). However, in the case of open innovation, the discussion is still incipient. Allameh and Khalilakbar (2018) argue that a proactive and risk-taking stance increases the potential for leveraging both internal and external knowledge to develop new products or services. It is important to note that entrepreneurial orientation is widely discussed in the literature, with numerous approaches exploring its impact on firm performance.

Freixanet et al. (2020) highlight that companies that embrace risk-taking practices are more attentive to seizing available information for innovation activities. Entrepreneurial orientation guides a company's efforts in capitalizing on business opportunities, thereby enhancing organizational performance (J. A. Zhang et al., 2018). This orientation, focused on seeking business opportunities, motivates the company to engage with external actors to leverage external resources for innovation (Carvalho & Sugano, 2016). Open innovation strategies leverage external channels to improve performance beyond the organization's boundaries (Schueffel, 2014). Adopting an open innovation perspective involves tapping into the knowledge of external actors to effectively support the innovation process (West et al., 2014). Given these considerations, studying the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and open innovation is important to contribute to the theoretical and empirical discourse regarding factors that facilitate innovation activities.

On the other hand, open innovation activities not only benefit from the strategic position adopted by the company but several studies have affirmed the importance of assimilation, dissemination, generation, and application of information within companies for organizational success (García-Villaverde et al., 2018; Hernández-Perlines & Xu, 2018). Absorptive capacity (ACAP) has received significant attention in the literature as an essential factor for navigating turbulent markets characterized by knowledge-based competition (Al Mamun et al., 2019; da Costa et al., 2018). The literature on absorptive capacity, commonly discussed within the theory of organizational learning (W. M. Cohen & Levinthal, 1989, 1990, 1994; Todorova & Durisin, 2007), highlights that the organizational mechanisms fostered by absorptive capacity enable enterprises to adapt more effectively to dynamic environments (Apriliyanti & Alon, 2017; Naqshbandi, 2016; W. Patterson & Ambrosini, 2015). Absorptive capacity is considered an ability that promotes creativity (Jiménez-Barrionuevo et al., 2019), supports the integration of new ideas (García-Villaverde et al., 2018), and facilitates the introduction of new products (Hughes et al., 2017).

Similarly, according to Zou et al. (2018), absorptive capacity is a skill that prompts organizations towards improved performance based on knowledge. When an organization has a well-defined strategic orientation, absorptive capacity enables the identification and utilization of available information to align efforts and resources with strategic objectives (Duchek, 2013). Numerous studies have explored how strategic orientation shapes the cognitive process for making strategic decisions through the effective use of information (Aljanabi, 2018; Aljanabi & Noor, 2015; Engelen et al., 2014; Hernandez-Perlines, 2018; Patel et al., 2015). This has significant implications for how organizations capitalize on market opportunities (van Doorn et al., 2017; Van Doorn et al., 2013). In the literature, the relationship between absorptive capacity and entrepreneurial orientation has consistently yielded similar results (Aljanabi, 2018; Gellynck et al., 2015). This highlights the crucial role of strategic positioning in generating and selecting the most suitable knowledge to meet organizational demands (Patel et al., 2015). However, there is a dearth of literature explicitly examining the direct effects of absorptive capacity on the capabilities that drive open innovation within firms, resulting in an incomplete understanding of the outcomes of such effects (Aljanabi, 2018). Hence, we propose to investigate the relationship between absorptive capacity and open innovation.

Despite the recurring theoretical discussion in the literature about the role of absorptive capacity in innovation (W. Patterson & Ambrosini, 2015; Wynarczyk et al., 2013), few studies have examined how knowledge exploitation activities contribute to enhancing innovation capabilities from a clear strategic standpoint (Hernández-Perlines & Xu, 2018). In this study, we also propose to assess the mediating effect of absorptive capacity on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and open innovation. Furthermore, the literature on the relationship between absorptive capacity and open innovation lacks comprehensive knowledge of the direct and indirect relationships, particularly as a mediating variable with other factors (Cui et al., 2018; Jasimuddin & Naqshbandi, 2019; Kokshagina et al., 2017; Naqshbandi & Kamel, 2017). Therefore, our study aims to analyze the effects of entrepreneurial orientation on absorptive capacity and open innovation, examine whether absorptive capacity significantly influences open innovation, and measure the mediating effects of absorptive capacity on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and open innovation. Given the conventional analysis of absorptive capacity in the literature, our study utilizes the concept of mediation to provide a better understanding of the open innovation ecosystem. It is worth mentioning that external information is not the same as external knowledge (Escribano et al., 2009). ACAP plays a crucial role in transforming external information into external knowledge, enabling firms to recognize value and develop open innovation processes (Aljanabi, 2018). We approach the valuable contribution of ACAP to the practices of innovation firms in adopting new knowledge for managing entrepreneurial attitudes from a different perspective. Enhancing proactive and risk-taking capacities is important to maximize the potential of innovation skills (Hernández-Perlines & Xu, 2018).

Therefore, this study aims to address the following research question: How can an organization enhance its open innovation through its absorptive capacity? The primary barriers to open innovation often involve the underutilization of information and knowledge. Given this, is it possible to establish a mediating effect of absorptive capacity in the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and open innovation? We address these approaches in an empirical study using the PLS-SEM statistical tool, taking a sample of 145 micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) located in Bogotá, Colombia.

Colombian enterprises face significant challenges in improving their competitiveness, particularly for small and medium enterprises that often prioritize short-term goals. According to the Private Council on Competitiveness (2019), investment in technology and innovation activities has doubled in the past decade, but it remains relatively low compared to other countries in Latin America. In 2018, investment in science, technology, and innovation activities accounted for 0.68% of the gross domestic product (GDP), while research and development investment was only 0.25% of GDP, based on data from the Colombian Observatory of Science and Technology. Only a few enterprises, typically larger ones operating in highly competitive markets, have achieved maturity in their innovation systems to yield significant results (Cotte Poveda & Andrade Parra, 2018).

The results of this study make three main contributions. Firstly, it provides empirical evidence of the relationships proposed in the theoretical research model within the context of SMEs in an emerging country like Colombia. Secondly, the comprehensive measurement of the model as a hierarchical component model helps fill gaps in the scientific literature, aligning with Zobel's (2017) call for the development of higher-order absorptive capacity models related to open innovation. Thirdly, this study contributes to the methodology by measuring the mediating effect of absorptive capacity using PLS-SEM and verifying it through the variance accounted for (VAF) and Zhao et al.'s (2010) procedure. Furthermore, we conducted an innovative analysis to assess and validate the predictive power of the research model using the cross-validated predictive ability test (CVPAT) introduced by Liengaard et al. (2021).

One of the most significant findings of this study is the validation of the impact of entrepreneurial orientation and absorptive capacity, as exogenous variables, in promoting innovativeness within firms.

This article is divided into six sections. Following the introduction, there is a literature review that focuses on the relationships between the variables under study and the formulation of research hypotheses. The subsequent section explains the methodology underlying this research. The analysis and discussion of the results, along with their implications, are presented thereafter. Finally, the article concludes with a discussion regarding the limitations of the study and suggestions for future research.

Literature reviewFrom a capabilities approach the resource-based view (RBV), the study variables are viewed as dynamic capabilities that companies utilize to navigate turbulent and challenging markets (Barney, 1988, 1991). Organizations focus their efforts on expanding their repertoire of resources and capabilities to compete with others (Teece et al., 2008). In this context, companies strive to create an enabling environment for knowledge, enabling them to implement intricate processes of assimilating, disseminating, managing, and exploiting information that fuels the innovation ecosystem (Huber et al., 2020). Drawing on the resource-based view and dynamic capabilities theory, the literature has extensively discussed the intricate relationships of open innovation (Naqshbandi, 2016; Naqshbandi & Kamel, 2017). However, there is a significant knowledge gap regarding how firms effectively leverage knowledge. When a firm adopts innovation assets, it becomes essential to transfer innovation data to other firms during project setup. The acquisition, assimilation, and transformation of information play a crucial role in establishing connections with external organizations (W. Patterson & Ambrosini, 2015). This paper proposes a model to maintain and exploit knowledge from a firm's strategic position, addressing the challenges associated with learning abilities in external innovation practices.

Open innovation (OI)The literature defines open innovation as the process of conducting innovation activities by leveraging external information received by a company (Cepeda-Carrion et al., 2023; Remneland-Wikhamn & Wikhamn, 2011). Open innovation is closely linked to organizational performance through the transfer of knowledge among various stakeholders connected to the company (Moretti & Biancardi, 2020).

From this perspective, innovation systems are shaped at multiple levels, including within the organization, outside the organization, between organizations, and within industries (Adamides & Karacapilidis, 2020). Therefore, when an enterprise lacks the necessary resources to provide value to its customers, it can compensate through open innovation by accessing external knowledge and technology (Chesbrough, 2003). Open innovation is also seen as a valuable approach that enables enterprises to gain competitive advantages and enhance organizational performance (Jasimuddin & Naqshbandi, 2019).

In this regard, open innovation serves as a value-generating model where enterprises exchange internal and external ideas and bring them to the market through external channels beyond their existing business scope (Chesbrough, 2003). Thus, open innovation can be viewed as a systematic and ongoing search process aimed at identifying new product or service opportunities and integrating them beyond the boundaries of the organization (Schueffel, 2014).

Entrepreneurial orientation (EO)Since the introduction of the EO concept (Miller, 1983; Mintzberg, 1973), three main components have been recognized that encompass the orientation towards having the willingness to risk capital to invest in better business opportunities, develop new ideas and make proactive decisions that address competitiveness: innovativeness, proactivity and risk-taking (Covin & Slevin, 1991). Bolton and Lane (2012) further expanded the understanding of EO by emphasizing the dynamic individual behaviors that drive the exploration of new opportunities. Individual characteristics, influenced by external conditions and social influences, shape the personality and attitudes that underlie entrepreneurial actions (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996).

EO is widely recognized as a crucial competitive tool (T. Wang et al., 2017) that enables enterprises to make strategic decisions and focus their efforts on seizing business opportunities (Ingram et al., 2022; van Doorn et al., 2017; Van Doorn et al., 2013), even in the face of risks (Lechner & Gudmundsson, 2014; Luu & Ngo, 2019). Its strategic relevance lies in its ability to guide organizations and their members toward improved organizational performance (Cuevas-Vargas et al., 2019; Jin et al., 2018; J. A. Zhang et al., 2018).

Absorptive capacityThe scientific literature has highlighted the importance of absorptive capacity as a predictor of innovation and knowledge transfer within organizations (W. M. Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). According to Zou et al. (2018), ACAP refers to an organization's ability to renew its knowledge base and achieve innovative outcomes. However, it should be noted that ACAP alone does not directly lead to improved financial performance. Instead, a company that can quickly absorb external knowledge and effectively transform it into products or services is more likely to enhance its financial performance by gaining competitive advantages (Zou et al., 2018).

ACAP is considered a dynamic capability that focuses on leveraging the available resources and managing the knowledge accessible to the organization (Duchek, 2013; Gao et al., 2017). The core processes of ACAP enable individuals within the organization to recognize the value of new ideas and effectively utilize external information for commercial purposes (W. Patterson & Ambrosini, 2015). Wynarczyk et al. (2013) emphasize that the development of human and capital resources is a crucial component of a company's ACAP, as it enables technological advancement and facilitates the access and utilization of external knowledge and technology. Therefore, innovative firms need to actively engage in continuous learning, information exchange, and knowledge integration with their external environment to effectively incorporate externally generated knowledge.

Entrepreneurial orientation, absorptive capacity, and open innovationNumerous studies have highlighted the significance of knowledge in the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation, absorptive capacity, and open innovation in the context of business opportunities and innovation (Feniser et al., 2017; Salehi et al., 2012). According to Naqshbandi (2016), collaborative relationships with various stakeholders in the value chain contribute to the improvement of processes and products. Thus, for a company engaged with external organizations, civil associations, government institutions, and other entities, the ability to acquire, transform, and effectively utilize knowledge aligned with innovation objectives becomes crucial.

Huang and Rice (2009) emphasized that the success of an innovation strategy relies on the organization's capacity to integrate both internal and external knowledge, with absorptive capacity playing a pivotal role in this process. The accurate interpretation and application of knowledge have significant implications for the firm's strategic decision-making (van Doorn et al., 2017). ACAP shapes the cognitive processes required to comprehend information and explore new strategic directions (Hughes et al., 2017).

Relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and ACAPFrom a strategic perspective, EO is closely linked to activities aimed at acquiring, assimilating, and applying knowledge, as these activities are critical for organizational success (García-Villaverde et al., 2018; Hernández-Perlines & Xu, 2018; Kohtamäki et al., 2019). The connection attained through EO requires the effective utilization of gathered information (Aljanabi, 2018; Aljanabi & Noor, 2015), which aids in informed decision-making (Hernandez-Perlines, 2018; Zhai et al., 2018). Various authors have examined the impact of EO on ACAP and have found similar results. For example, Shih (2018) discovered that innovativeness increases the likelihood of investing in the creation, transformation, and dissemination of knowledge for the purpose of innovation. Similarly, proactive firms are willing to take risks and capitalize on opportunities that promote the adoption of new processes, leading small and medium enterprises to actively capture information from external sources for their benefit (Ato Sarsah et al., 2020). Seepana et al. (2021) highlight that proactivity enhances the range of knowledge available, facilitating incremental or radical improvements through absorptive capacity. Studies by Aljanabi (2018), Aljanabi and Noor (2015), Gellynck et al. (2015), and Patel et al. (2015) have all shown significant effects, supporting the pivotal role of EO in proactively filtering and generating appropriate information to inform decision-making. Based on these arguments, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Entrepreneurial orientation significantly impacts the absorptive capacity of Colombian MSMEs.

Relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and open innovationEmpirical knowledge regarding the impact of EO on OI is still limited, and there is no consensus on the role of entrepreneurial abilities in OI (Carvalho & Sugano, 2016; De Cleyn et al., 2013; Hossain, 2013; Hung & Chiang, 2010). While numerous studies have demonstrated the direct relationship between the utilization of external networks and innovation (Baker et al., 2016; Kollmann & Stöckmann, 2014), recent research suggests that effective innovation requires the strategic utilization of external knowledge, involving investment and risk-taking as means to shape the organizational posture (Fellnhofer, 2019; Genc et al., 2019; Xia & Roper, 2016). The support that EO provides in exploiting external information is essential for SMEs to increase their income by introducing new products or services to the market (Freixanet et al., 2021). The inclination of companies towards innovation, proactivity, and risk-taking is a critical element in reducing the high levels of uncertainty associated with OI projects (Najar & Dhaouadi, 2020). Despite these insights, the impact of EO on innovation capabilities, specifically in terms of knowledge acquired from external partners, remains largely unexplored.

In emerging countries, intense competition based on offering the lowest prices is a common practice that often leads to unprofitable and unsustainable supply chains. As a result, differentiation becomes a viable alternative strategy. Consequently, enterprises increasingly adopt EO strategies, encompassing innovation, proactivity, and risk-taking, to enhance their innovation performance, improve core competitiveness, and increase financial outcomes (Zhai et al., 2018). The concept of OI—coined by Chesbrough (2003)— has prompted enterprises to seek innovation by involving external actors and knowledge in their processes (West et al., 2014). This has sparked growing interest in examining the relationship between EO and OI (Carvalho & Sugano, 2016; De Cleyn et al., 2013; Hossain, 2013; Hung & Chiang, 2010). Some studies have found that EO significantly influences OI (Carvalho & Sugano, 2016; Hossain, 2013). Similarly, a study by Cheng and Huizingh (2014) discovered that EO drives OI in service enterprises in Asia, with EO being associated with proactive and entrepreneurial processes that create fertile ground for open innovation. Additionally, Hung and Chiang (2010) found that EO contributes to successful OI implementation by helping organizations effectively identify opportunities in their environment and enhancing enterprise proactivity, leading to improved performance.

EO is especially important when executing OI-based strategies. Prior research has highlighted the significance of proactive behavior and risk-taking attitudes in enhancing the outcomes of innovation activities (Allameh & Khalilakbar, 2018; Su et al., 2020; Zhai et al., 2018). Freixanet et al. (2020) specifically emphasize that companies with a strong EO are better equipped to capture external information for developing new products or services, as they are more attuned to market demands. Being prepared to make bold decisions increases the likelihood of companies embracing adventurous practices and effectively leveraging knowledge to drive innovation (Najar & Dhaouadi, 2020). In line with this perspective, authors such as Najar and Dhaouadi (2020) have emphasized that analyzing OI in firms is incomplete without considering the entrepreneurial skills and willingness to seize business opportunities without aversion to risk. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: Entrepreneurial orientation significantly impacts open innovation in Colombian MSMEs.

Relationship between absorptive capacity and open innovationFlor et al. (2013) argue that ACAP and OI, although belonging to the field of innovation management, are connected variables that have rarely been jointly discussed in the scientific literature until recently. However, empirical evidence demonstrates a significant impact of ACAP on OI (Cuevas-Vargas et al., 2022; Jasimuddin & Naqshbandi, 2019; Kim et al., 2016; Laviolette et al., 2016; Naqshbandi, 2016; Naqshbandi & Kamel, 2017). Additionally, Kim et al. (2016) found that enterprises can develop ACAP for OI by engaging in closed and open inbound innovation activities in a repeated and alternating manner, enhancing organizational awareness.

Laviolette et al. (2016) concluded that employee-driven innovation showed a catalyzing effect on various levels in terms of ACAP and that innovation openness comes from within an organization. Naqshbandi (2016), in a study of enterprises in the United Arab Emirates, found that realized ACAP significantly influences OI by improving enterprises' ability to efficiently apply newly acquired knowledge, leading to successful integration and utilization. The study also revealed the mediating role of ACAP in the relationship between managerial bonds and OI. Similarly, Naqshbandi and Kamel (2017) concluded that realized ACAP in emerging-economy enterprises is positively and significantly related to inbound and outbound OI. Therefore, enterprises need to leverage their systems and procedures to transform, exploit, and exchange knowledge, benefiting from external sources.

Jasimuddin and Naqshbandi (2019), in a study of SMEs in France, found that ACAP has a positive and significant impact on OI. They also demonstrated the mediating role of ACAP in the relationship between knowledge infrastructure capacity and OI. Mirza et al. (2022) concluded that the relationship between OI and strategic positioning is enhanced when firms establish a research zone to develop new knowledge. Similarly, Cuevas-Vargas et al. (2022) found that ACAP significantly influences open innovation. However, organizations need to develop their capacities and be receptive to leveraging internal and external information to enhance their open innovation capability. Based on these arguments, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: Absorptive capacity significantly impacts open innovation in Colombian MSMEs.

The mediating role of ACAP in the relationship between EO and OIThe debate surrounding ACAP has gained significant attention among scholars who have explored internal resources as mechanisms driving an open innovation strategy (Mirza et al., 2022; Russo-Spena & Di Paola, 2019). Ahn et al. (2016) argue that enterprises can enhance their inclination towards openness by willingly collaborating, sharing experiences, and trusting external partners, when their managers are more inclined towards collaboration. This openness facilitates the development of various OI-related capabilities, including ACAP. Escribano et al. (2009) support this argument by highlighting that enterprises with high levels of ACAP are more efficient in managing external knowledge flow, which lead to innovative outcomes and competitive advantages.

The scientific literature emphasizes the importance of exploring the relationships between ACAP and OI in developing economies to generate generalizable findings for enterprise decision-making. Not only have direct relationships between these variables been identified, but the mediating role of ACAP in the relationship between exogenous variables and OI has also been acknowledged. For instance, Aljanabi (2018) found that ACAP partially mediates the relationship between EO and the technological innovation capabilities of industrial SMEs in Iraq. Hernández-Perlines and Xu (2018) concluded that ACAP mediates the relationship between international EO and the international success of family enterprises in Spain, with ACAP playing a crucial role in maximizing the potential of the model and explaining up to 40.6% of the variation in international performance.

Jasimuddin and Naqshbandi (2019) supported the weak or partial mediating role of ACAP in the relationship between knowledge infrastructure capacity and OI. Similarly, Al Mamun et al. (2019), in a study of SMEs in Malaysia, found that ACAP partially mediates the relationship between strategic orientations (entrepreneurial, client, and market-based) and innovation. They demonstrated that EO has positive and significant direct effects on innovation and indirect effects through ACAP, indicating the partial mediation of ACAP. Based on these findings, the final research hypothesis is proposed:

H4: Absorptive capacity mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and open innovation in Colombian MSMEs.

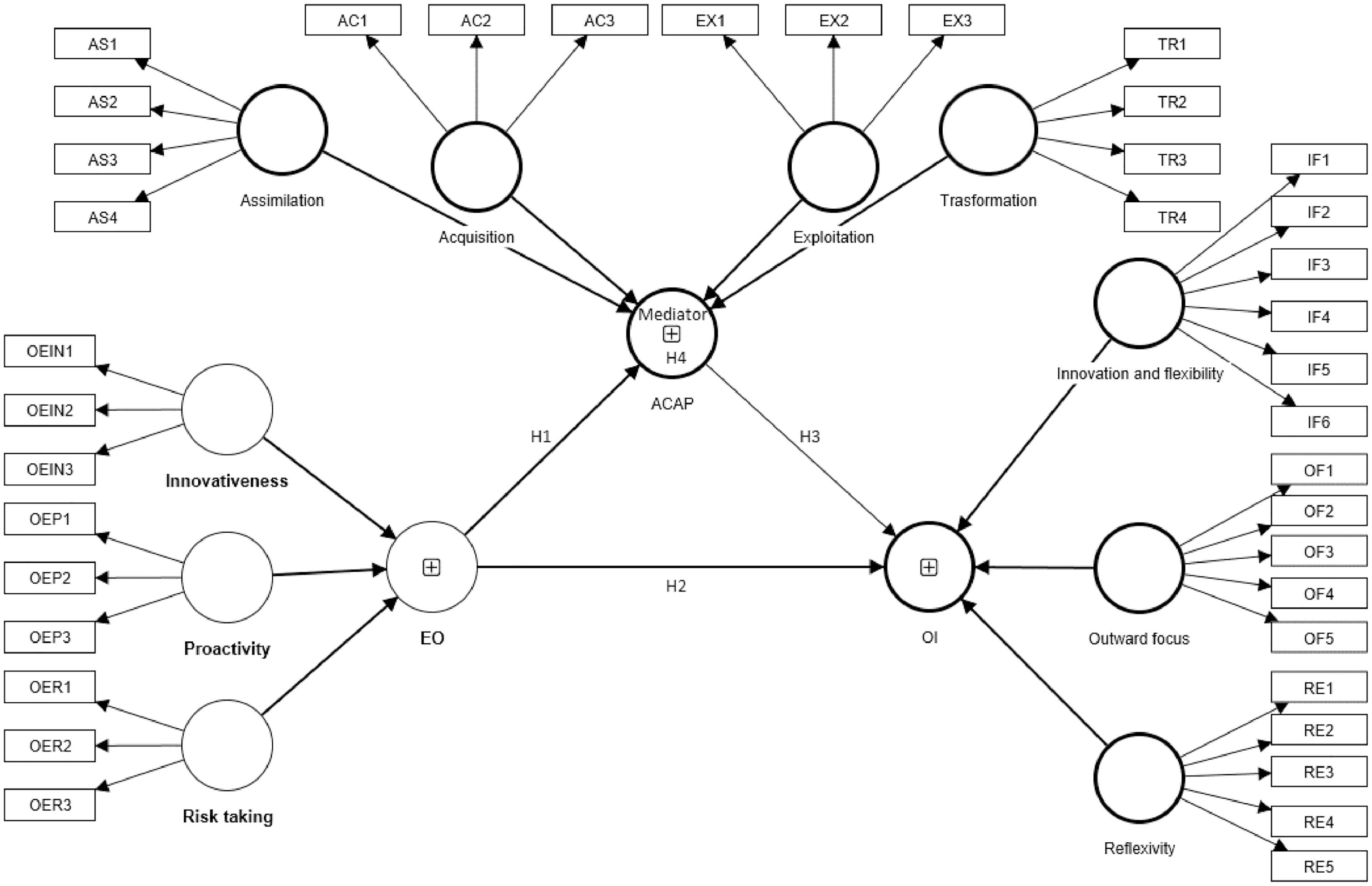

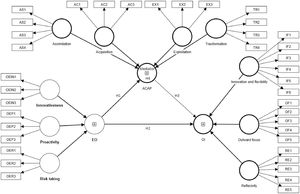

Fig. 1 shows the theoretical model that was used to formulate this study's hypotheses.

MethodThe present empirical study had a cross-sectional quantitative approach with a non-experimental design. The statistical technique used was partial least squares structural equation modeling conducted using statistical software SmartPLS 4 (Ringle et al., 2022). PLS-SEM, a second-generation statistical technique, was chosen due to its suitability for working with small sample sizes and nonparametric tests that address potential issues related to data normality (Hair et al., 2017).

Furthermore, there has been a growing trend in various scientific fields, including computer sciences, engineering, environmental sciences, medicine, psychology, sociology, and political sciences, where researchers using SEM prefer PLS-SEM over CB-SEM. PLS-SEM is favored because “it offers a wide range of advanced analysis techniques and complementary methods, facilitating the handling of complex analytical tasks” (Becker et al., 2023, p. 322). It also allows for the simultaneous consideration of reflective and formative models (Becker et al., 2012).

In this study, PLS-SEM was implemented by estimating the model as a hierarchical component model Type II (reflective-formative mode) (Becker et al., 2012; Lohmöller, 1989). The two-stage embedded approach technique was employed, as recommended by Becker et al. (2012), Ringle et al. (2012), and Sarstedt et al. (2019). Firstly, the measurement model was estimated using the two-stage method. Then, the common method variance (CMV) was assessed to ensure that it does not affect the outcomes of this study. Subsequently, the structural model was evaluated to test the research hypotheses and measure the indirect effects of entrepreneurial orientation on open innovation to determine the mediating effect of absorptive capacity in the EO-OI relationship. Bootstrapping with 10,000 subsamples was employed to estimate the significance of the indirect effects (Hair et al., 2022). Additionally, the predictive power of the structural model was assessed to evaluate its out-of-sample predictive ability (Shmueli et al., 2016).

Sample design and data collectionThis research utilized the database of the Bogotá Chamber of Commerce (2018) as the source for the study's population, which consisted of economic units in the Department of Bogota, Colombia. The population encompassed 135,931 enterprises with a workforce size ranging from 1 to 200 employees. The sample design involved the selection of 267 enterprises through random sampling, aiming for a 95% confidence level and a 6% margin of error, following the guidelines of Sekaran and Bougie (2016).

Data collection was conducted using a questionnaire specifically designed for completion by top managers or owners of the targeted companies. The survey was administered through personal interviews with the top managers or owners of the 267 firms selected for the sample. However, valid responses were obtained from only 145 surveys, resulting in a response rate of 54.3%. These 145 valid surveys were used as the sample for the present study, collected between February and April 2018.

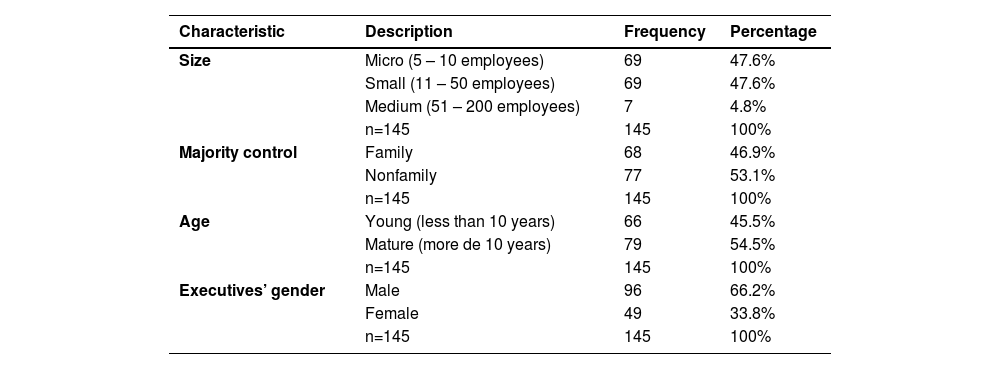

Sample profileWithin the total sample, the majority of the enterprises were micro- and small-sized, with 47.6% classified as micro, 47.6% as small, and only 4.8% as medium-sized enterprises. Furthermore, the majority of the enterprises (53.1%) were non-family-owned. In terms of maturity, 54.5% of the enterprises have been in operation for over ten years. The leadership roles were predominantly held by men, accounting for 66.2% of the sample, while women were represented with only 33.8%. In terms of sector representation, the services sector comprised the majority, accounting for 55.2% of the sample, while the remaining enterprises belonged to the industrial sector, as shown in Table 1.

General data of the sampled enterprises.

| Characteristic | Description | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size | Micro (5 – 10 employees) | 69 | 47.6% |

| Small (11 – 50 employees) | 69 | 47.6% | |

| Medium (51 – 200 employees) | 7 | 4.8% | |

| n=145 | 145 | 100% | |

| Majority control | Family | 68 | 46.9% |

| Nonfamily | 77 | 53.1% | |

| n=145 | 145 | 100% | |

| Age | Young (less than 10 years) | 66 | 45.5% |

| Mature (more de 10 years) | 79 | 54.5% | |

| n=145 | 145 | 100% | |

| Executives’ gender | Male | 96 | 66.2% |

| Female | 49 | 33.8% | |

| n=145 | 145 | 100% |

Source: Own elaboration based on research results.

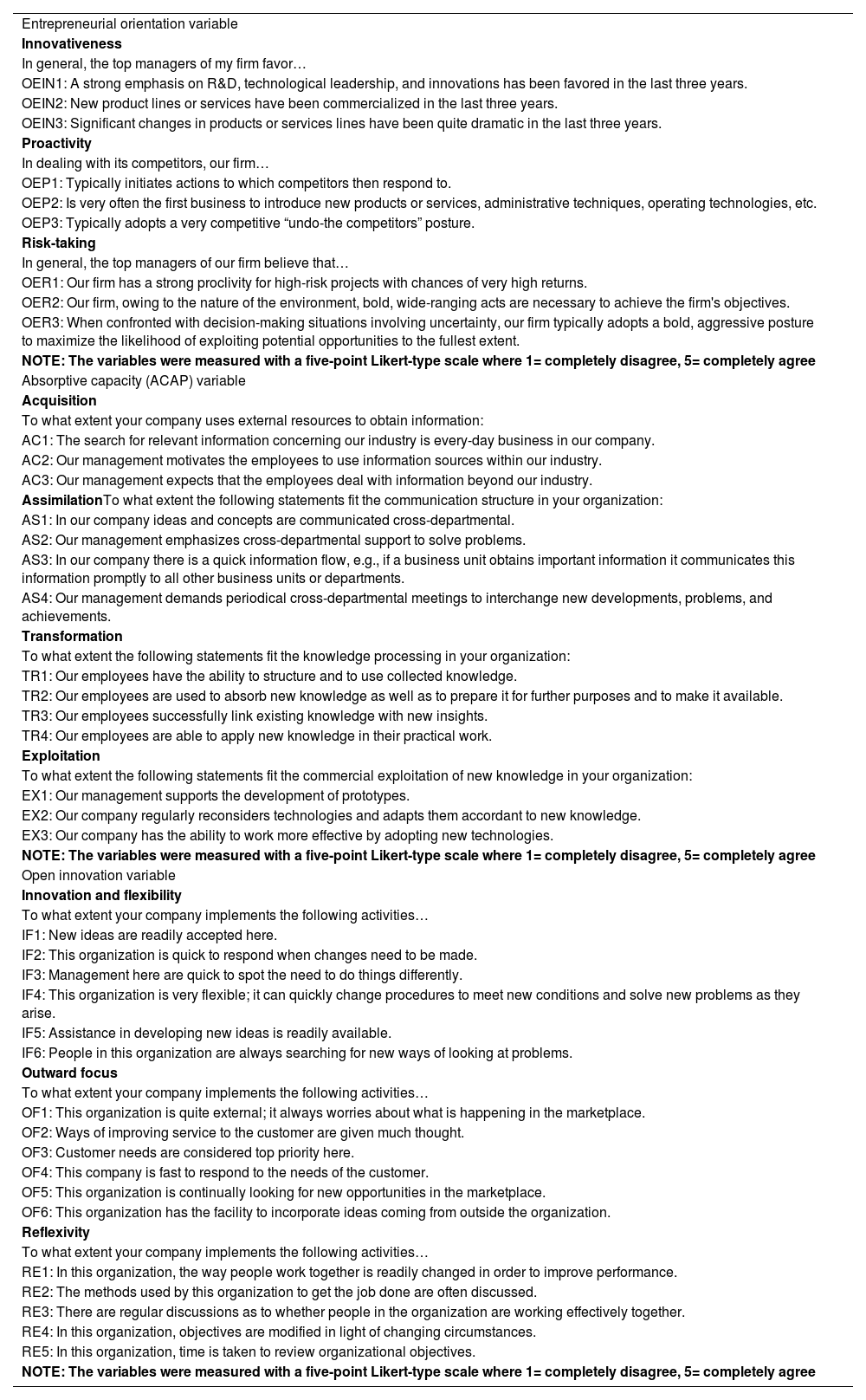

A higher-order-construct (HOC), based on Covin and Slevin (1991)), was employed to measure the strategic orientation towards entrepreneurship in three distinct dimensions, which were reflectively specified (Jarvis et al., 2003; MacKenzie et al., 2005). The three dimensions are as follows: (1) innovativeness, assessed using three items (e.g., "Our firm has placed a strong emphasis on R&D, technological leadership, and innovation over the past three years."); (2) proactivity, measured through three items (e.g., "Our firm typically takes the initiative in actions to which competitors then respond."); and (3) risk-taking, evaluated using three items (e.g., "Our firm shows a strong inclination for high-risk projects with the potential for very high returns."). According to our proposed model, the uni-dimensional conceptualization emphasizes the collective impact of the entrepreneurial orientation dimensions, incorporating them in a consolidated manner (Wales et al., 2013). All items were measured on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from "completely disagree" (1) to "completely agree" (5) (see Appendix 1). This construct was specified as a type II model (reflective-formative mode), following the criteria outlined by MacKenzie et al. (2005).

Absorptive capacityA higher-order-construct, adapted from Flatten et al. (2011), was utilized to measure absorptive capacity. This HOC encompasses four dimensions, which were reflectively specified (Jarvis et al., 2003; MacKenzie et al., 2005). The dimensions are as follows: (1) knowledge acquisition, assessed using three items (e.g., "Our management encourages employees to utilize information sources within our industry."); (2) knowledge assimilation, evaluated through four items (e.g., "Ideas and concepts are communicated across departments in our company."); (3) knowledge transformation, measured with four items (e.g., "Our employees possess the ability to structure and apply acquired knowledge."); and (4) knowledge exploitation, gauged using four items (e.g., "Our company regularly reevaluates technologies and adjusts them in accordance with new knowledge."). All items were measured on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from "completely disagree" (1) to "completely agree" (5) (see Appendix 1). This construct was specified as a type II model (reflective-formative mode), following the criteria outlined by MacKenzie et al. (2005).

Open innovationA higher-order-construct, adapted from Remneland-Wikhamn and Wikhamn (2011), was employed to measure the open innovation climate. This HOC consists of three lower-order constructs, which were reflectively specified (Jarvis et al., 2003; MacKenzie et al., 2005). The first construct is related to innovation challenges, while the other two pertain to openness challenges. Specifically, the constructs are as follows: (1) innovation and flexibility, comprising of six items that measure the organization's orientation towards change and the degree of support and encouragement for new ideas and innovative approaches (M. G. Patterson et al., 2005); (2) outward focus, consisting of six items that assess the organization's responsiveness to client needs and the broader market (M. G. Patterson et al., 2005); (3) reflexivity, comprising of five items that facilitate the review and reflection on objectives, strategies, and work processes to adapt to the wider environment (M. G. Patterson et al., 2005).

All items were measured on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from "completely disagree" (1) to "completely agree" (5) (see Appendix 1). This construct was specified as a type II model (reflective-formative mode), following the criteria outlined by MacKenzie et al. (2005).

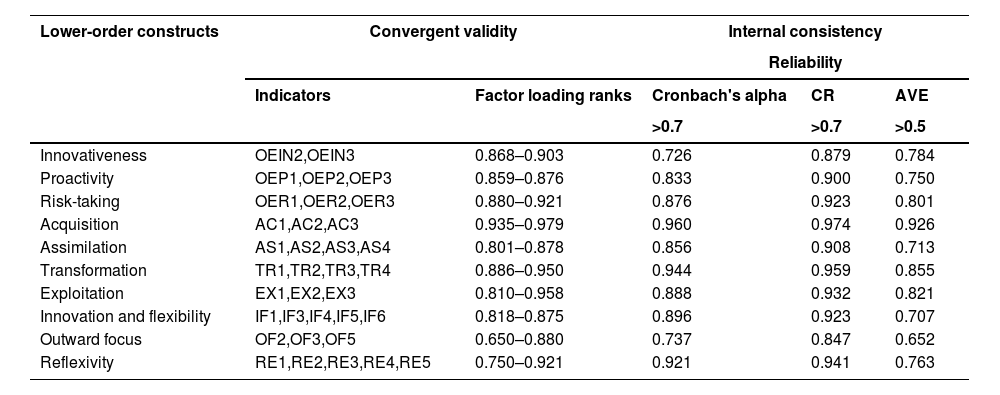

Reliability and validityIn the first stage the measurement model was assessed. The results obtained through the PLS algorithm demonstrate high internal consistency for the ten lower-order reflective constructs. The composite reliability (CR) values exceed the recommended threshold of 0.7 as suggested by Hair et al. (2017). Additionally, Cronbach's alpha coefficients for each construct are higher than 0.7, as recommended by Nunnally and Bernstein (1994)). Moreover, all constructs have average variance extracted (AVE) values exceeding the threshold of 0.5, indicating convergent validity according to Fornell and Larcker (1981) and Hair et al. (2012). These findings are presented in Table 2.

Evaluation of the reflective measuring model – stage 1.

| Lower-order constructs | Convergent validity | Internal consistency | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reliability | |||||

| Indicators | Factor loading ranks | Cronbach's alpha | CR | AVE | |

| >0.7 | >0.7 | >0.5 | |||

| Innovativeness | OEIN2,OEIN3 | 0.868–0.903 | 0.726 | 0.879 | 0.784 |

| Proactivity | OEP1,OEP2,OEP3 | 0.859–0.876 | 0.833 | 0.900 | 0.750 |

| Risk-taking | OER1,OER2,OER3 | 0.880–0.921 | 0.876 | 0.923 | 0.801 |

| Acquisition | AC1,AC2,AC3 | 0.935–0.979 | 0.960 | 0.974 | 0.926 |

| Assimilation | AS1,AS2,AS3,AS4 | 0.801–0.878 | 0.856 | 0.908 | 0.713 |

| Transformation | TR1,TR2,TR3,TR4 | 0.886–0.950 | 0.944 | 0.959 | 0.855 |

| Exploitation | EX1,EX2,EX3 | 0.810–0.958 | 0.888 | 0.932 | 0.821 |

| Innovation and flexibility | IF1,IF3,IF4,IF5,IF6 | 0.818–0.875 | 0.896 | 0.923 | 0.707 |

| Outward focus | OF2,OF3,OF5 | 0.650–0.880 | 0.737 | 0.847 | 0.652 |

| Reflexivity | RE1,RE2,RE3,RE4,RE5 | 0.750–0.921 | 0.921 | 0.941 | 0.763 |

NOTE: The t-values for all the factor loadings were significant (p<0.001).

Source: Own calculation based on results obtained with SmartPLS 4. Ringle et al. (2022).

Furthermore, the factor loadings of the indicators (manifest variables) are above 0.7 (Hair et al., 2017), except for variable OF3, which has a factor loading of 0.650. However, according to Bagozzi and Yi (1988), this loading is still considered acceptable as it surpasses the critical value of 0.6. Additionally, all factor loadings are statistically significant (p<0.001), indicating the reliability of each indicator. Furthermore, since the AVE values are above 0.5 for all constructs, there is assurance of convergent validity for the employed scales as recommended by Hair et al. (2017).

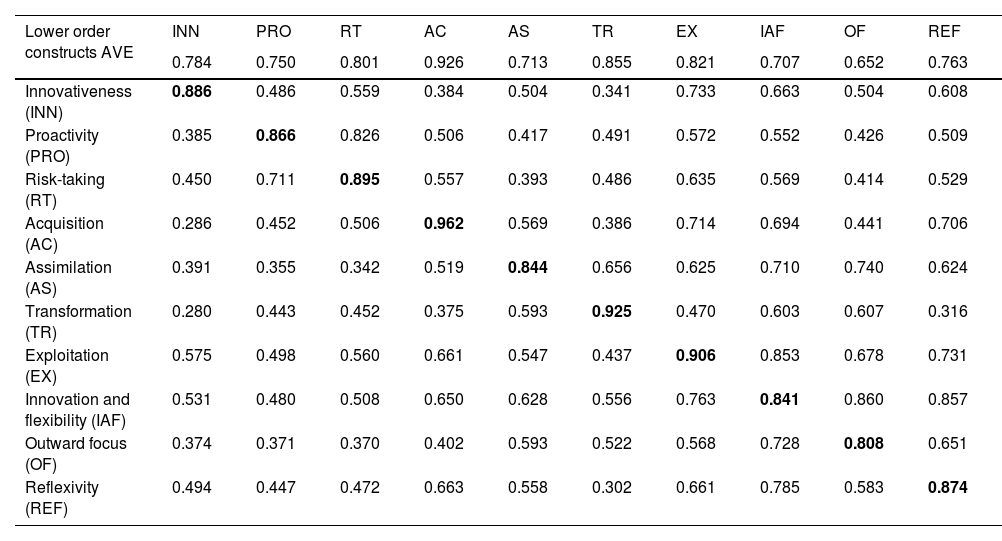

The discriminant validity of the lower-order constructs in the present study was assessed using two methods: The heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) test and the Fornell–Larcker criterion. The HTMT test values, shown above the diagonal in Table 3, were calculated to determine the discriminant validity of the constructs. These values were found to be below the threshold of 0.90, as recommended by Gold et al. (2001), Henseler et al. (2015), and Teo et al. (2008), indicating satisfactory discriminant validity.

Discriminant validity of the lower-order constructs – stage 1.

| Lower order constructs AVE | INN | PRO | RT | AC | AS | TR | EX | IAF | OF | REF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.784 | 0.750 | 0.801 | 0.926 | 0.713 | 0.855 | 0.821 | 0.707 | 0.652 | 0.763 | |

| Innovativeness (INN) | 0.886 | 0.486 | 0.559 | 0.384 | 0.504 | 0.341 | 0.733 | 0.663 | 0.504 | 0.608 |

| Proactivity (PRO) | 0.385 | 0.866 | 0.826 | 0.506 | 0.417 | 0.491 | 0.572 | 0.552 | 0.426 | 0.509 |

| Risk-taking (RT) | 0.450 | 0.711 | 0.895 | 0.557 | 0.393 | 0.486 | 0.635 | 0.569 | 0.414 | 0.529 |

| Acquisition (AC) | 0.286 | 0.452 | 0.506 | 0.962 | 0.569 | 0.386 | 0.714 | 0.694 | 0.441 | 0.706 |

| Assimilation (AS) | 0.391 | 0.355 | 0.342 | 0.519 | 0.844 | 0.656 | 0.625 | 0.710 | 0.740 | 0.624 |

| Transformation (TR) | 0.280 | 0.443 | 0.452 | 0.375 | 0.593 | 0.925 | 0.470 | 0.603 | 0.607 | 0.316 |

| Exploitation (EX) | 0.575 | 0.498 | 0.560 | 0.661 | 0.547 | 0.437 | 0.906 | 0.853 | 0.678 | 0.731 |

| Innovation and flexibility (IAF) | 0.531 | 0.480 | 0.508 | 0.650 | 0.628 | 0.556 | 0.763 | 0.841 | 0.860 | 0.857 |

| Outward focus (OF) | 0.374 | 0.371 | 0.370 | 0.402 | 0.593 | 0.522 | 0.568 | 0.728 | 0.808 | 0.651 |

| Reflexivity (REF) | 0.494 | 0.447 | 0.472 | 0.663 | 0.558 | 0.302 | 0.661 | 0.785 | 0.583 | 0.874 |

NOTE: The numbers on the diagonal (in bold) represent the square root of the AVE values. Above the diagonal, the HTMT.90 relation of correlations test is shown; below the diagonal, the Fornell–Larcker test is shown.

Source: Own calculation based on results obtained with SmartPLS 4. Ringle et al. (2022).

Furthermore, the Fornell–Larcker criterion was applied using the square root of each construct's average variance extracted. The values in bold on the diagonal of the table represent the square roots of the AVE for each construct. According to Fornell and Larcker (1981), these values should be higher than the correlations between the construct and any other construct in the model, which is indicated below the diagonal. Based on the Fornell–Larcker criterion, the results confirm the discriminant validity of the constructs.

Overall, these findings demonstrate that the data in this study are reliable and valid, supporting the hypotheses proposed using PLS-SEM.

Next, we proceeded with the second stage of estimating the measurement model, where the construct scores generated in the first stage were used as indicators to measure the hierarchical component model in a formative manner.

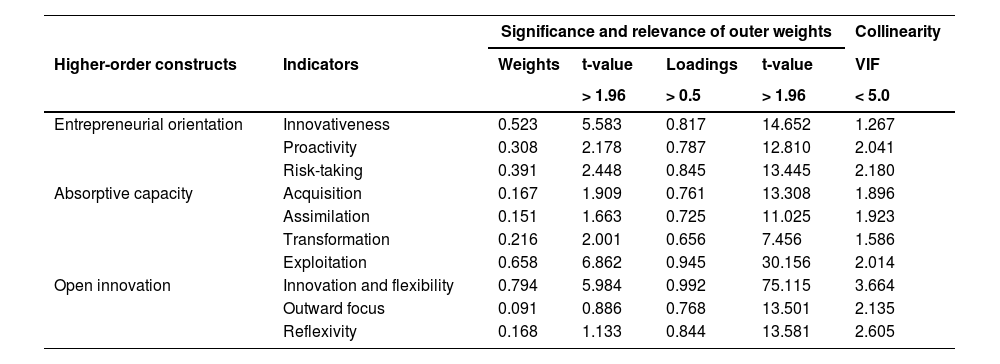

To validate the reflective-formative higher-order model, we followed the recommendations of Hair et al. (2017) to establish the convergent validity of the higher-order constructs. Firstly, we assessed collinearity to ensure that the HOC measurement model was not negatively affected. The variance inflation factor (VIF) values of the lower-order constructs, shown in Table 4, did not exceed the threshold value of 5.0 (Hair et al., 2017), indicating no issues with collinearity.

Higher-order constructs validity – stage 2.

| Significance and relevance of outer weights | Collinearity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Higher-order constructs | Indicators | Weights | t-value | Loadings | t-value | VIF |

| > 1.96 | > 0.5 | > 1.96 | < 5.0 | |||

| Entrepreneurial orientation | Innovativeness | 0.523 | 5.583 | 0.817 | 14.652 | 1.267 |

| Proactivity | 0.308 | 2.178 | 0.787 | 12.810 | 2.041 | |

| Risk-taking | 0.391 | 2.448 | 0.845 | 13.445 | 2.180 | |

| Absorptive capacity | Acquisition | 0.167 | 1.909 | 0.761 | 13.308 | 1.896 |

| Assimilation | 0.151 | 1.663 | 0.725 | 11.025 | 1.923 | |

| Transformation | 0.216 | 2.001 | 0.656 | 7.456 | 1.586 | |

| Exploitation | 0.658 | 6.862 | 0.945 | 30.156 | 2.014 | |

| Open innovation | Innovation and flexibility | 0.794 | 5.984 | 0.992 | 75.115 | 3.664 |

| Outward focus | 0.091 | 0.886 | 0.768 | 13.501 | 2.135 | |

| Reflexivity | 0.168 | 1.133 | 0.844 | 13.581 | 2.605 | |

Source: Own calculation based on results obtained with SmartPLS 4. Ringle et al. (2022).

Secondly, we examined the significance and absolute contribution of the outer weights (relative importance) to ensure the validity of the formative indicators. Some indicators (e.g., acquisition, assimilation, outward focus, and reflexivity) were not statistically significant. Therefore, the outer loadings of the formative indicators were analyzed. It was found that all of the outer loadings were both greater than 0.5 and statistically significant (Sarstedt et al., 2019). By meeting all the criteria for establishing higher-order construct validity, the validity of the HOC was established, allowing for the evaluation of the structural model.

Common method variance (CMV)To address the potential issue of common method variance, several post-hoc techniques were employed to ensure that CMV does not affect the interpretation of the results (Rodríguez-Ardura & Meseguer-Artola, 2020).

Firstly, Harman's single factor test was conducted by performing an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with all indicators. The un-rotated first factor provided information regarding 42.71% of the variance, which is lower than the threshold of 50% for all observed variables, including the dependent variable. Therefore, CMV is not a concern for the structural equation model analysis (Podsakoff & Organ, 1986).

Additionally, the full collinearity test proposed by Kock (2015) was applied to examine the presence of CMV in the PLS-SEM. This test utilizes the inner variance inflation factor values of the latent variables. To indicate the absence of CMV, the VIF values should be below the critical value of 3.3. In this study, none of the latent constructs (EO, ACAP, and OI) exceeded the threshold, with respective VIF values of EO = 1.113, ACAP = 1.357, and OI = 1.426. Therefore, based on the results of the full collinearity test, there is no issue with CMV (Kock, 2015).

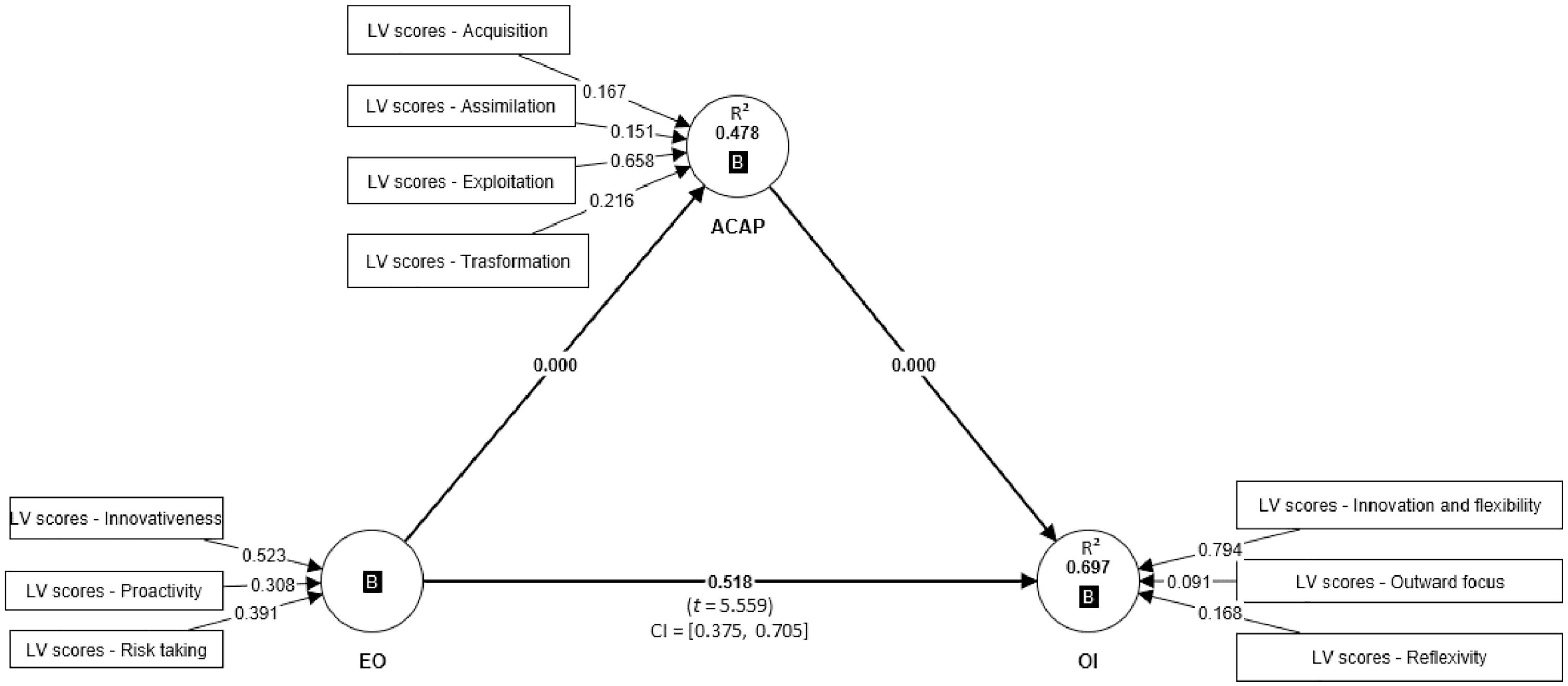

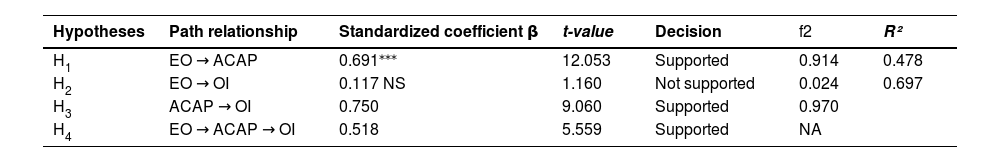

ResultsTo test the research hypotheses, the structural model was evaluated using bootstrapping. The results, presented in Table 5, provide sufficient empirical evidence to determine confidence intervals and assess the precision of the estimated parameters. The findings indicate that the structural model has predictive relevance, as OI is explained by EO and ACAP with an R-squared value of 0.697, while ACAP is explained by EO with an R-squared value of 0.478. These values suggest that OI and ACAP, as endogenous constructs, have substantial explanatory power, as their R-squared values are well above the recommended threshold of 0.20 (Chin, 1998).

Results of the structural model with PLS-SEM.

| Hypotheses | Path relationship | Standardized coefficient β | t-value | Decision | f2 | R² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | EO → ACAP | 0.691⁎⁎⁎ | 12.053 | Supported | 0.914 | 0.478 |

| H2 | EO → OI | 0.117 NS | 1.160 | Not supported | 0.024 | 0.697 |

| H3 | ACAP → OI | 0.750 | 9.060 | Supported | 0.970 | |

| H4 | EO → ACAP → OI | 0.518 | 5.559 | Supported | NA |

Significance: ** p<0.05; *** p<0.001; NS = Non-significant.

Effect size f2: >0.02= Small; >0.15 = Medium; >0.35 = Large (J. Cohen, 1988).

R2 Values: > 0.10 (Falk & Miller, 1992); >0.20 = Weak; >0.33 Moderate; >0.67 = Substantial (Chin, 1998).

Source: Own calculation based on results obtained with SmartPLS 4. Ringle et al. (2022).

Furthermore, a post-hoc analysis was conducted to compute the achieved statistical power using G*Power 3.1.9.7 (Faul et al., 2009). The f2 effect sizes were calculated based on the R-squared values of the endogenous variables. For OI, the calculated effect size f2 was 0. 8348, and for ACAP, it was 0.6913. With a significance level of α = 0.01 and a total sample size of 145, both predictors achieved a statistical power (1 − β err prob) of 1.000, surpassing the critical t-value of 2.3527. These results indicate that the research model has sufficient statistical power to detect meaningful effects (Faul et al., 2009), further confirming its robustness and relevance for decision-making in enterprises.

Regarding the first hypothesis H1, the results—shown in Table 5 (β = 0.691, p<0.001)— provide empirical evidence supporting the positive and significant effects of EO on ACAP, thus confirming H1. The findings indicate that EO has a 69.1% impact on ACAP, which is considered a truly large effect based onJ. Cohen's (1988) test, with an f2value of 0.914. These results align with the findings of Gellynck et al. (2015) in their study on agricultural businesses in Ecuador, where they concluded that the innovative EO of farmers is positively related to their capacity to absorb and apply external knowledge. The results also support the findings of Aljanabi (2018) in a study on SMEs in Kurdistan, which revealed a significant impact of EO on ACAP in SMEs.

Concerning H2, the results show that EO has a positive effect on OI, although it is not statistically significant (β = 0.117, NS). Therefore, H2 is not supported, as the positive effect of EO on OI was small (11.7%) and did not reach statistical significance. Based onJ. Cohen's (1988) test, this effect size is considered small, with an f2 value of 0.024, indicating that EO has a limited contribution to the predictive power of OI in Colombian MSMEs. These findings contradict previous studies such as Hung and Chiang (2010), Cheng and Huizingh (2014), Hossain (2013)), and Carvalho and Sugano (2016), which concluded that EO significantly impacts OI.

Regarding hypothesis H3, the results demonstrate that ACAP has a positive and significant effect on OI in MSMEs (β = 0.750, p<0.001). Therefore, H3 is supported as ACAP was found to have a substantial 75.0% impact on OI. According toJ. Cohen's (1988) test, this effect size is considered large, with an f2 value of 0.970, indicating that the ACAP infrastructure strongly contributes to the predictive power of OI in Colombian MSMEs. These findings align with the results of Naqshbandi (2016), who found that realized ACAP significantly impacts OI, allowing enterprises to improve their ability to efficiently exploit new knowledge to integrate it and use it successfully. Likewise, the results confirm the findings of Naqshbandi and Kamel (2017) which led to the conclusion that ACAP positively and significantly affects the inbound and outbound OI of developing enterprises.

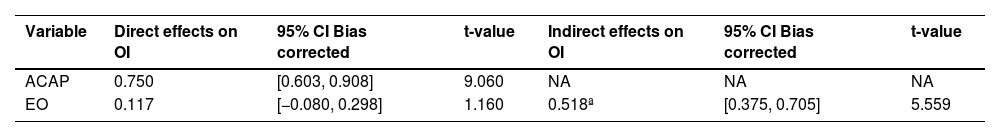

On the other hand, the indirect effects were examined to assess the mediating role of ACAP in the relationship between EO and OI, revealing a significant indirect effect (β = 0.518, p<0.001), as shown in Fig. 2.

The indirect effect analysis was conducted following the guidelines proposed by Zhao et al. (2010) for evaluating mediating effects in PLS, which have been shown to outperform Baron and Kenny's approach (Hair et al., 2017). In this regard, the indirect effect (p1 * p2) was tested, the magnitude of the mediation was estimated, and the significance of the mediating effect was assessed using bias-corrected confidence intervals (CI) with 10,000 subsamples at a 95% confidence level. The results indicate that the indirect effect is significantly different from zero, providing evidence for the strength and magnitude of the mediation of ACAP. Please refer to Table 6 for more details on the empirical findings, demonstrating the significant indirect effect of EO on OI through ACAP.

Mediated effects of ACAP on OI.

| Variable | Direct effects on OI | 95% CI Bias corrected | t-value | Indirect effects on OI | 95% CI Bias corrected | t-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACAP | 0.750 | [0.603, 0.908] | 9.060 | NA | NA | NA |

| EO | 0.117 | [−0.080, 0.298] | 1.160 | 0.518ª | [0.375, 0.705] | 5.559 |

NOTE: The 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals are performed where zero is not presented, thereby demonstrating the strength and magnitude of the mediation.

EO total effect on OI (β = 0.635, p<0.001).

Source: Own contribution from results obtained with SmartPLS 4. Ringle et al. (2022).

ªObtained from the effects of EO on ACAP (0.691) multiplied by the effects of ACAP on OI (0.750).

Moreover, based on Zhao et al.'s (2010) criteria, the mediating effect of ACAP can be considered full mediation (indirect-only mediation) since the indirect effect is significant while the direct effect is not. This empirical finding provides evidence for the mediating role of ACAP in the relationship between EO and OI, indicating that ACAP serves as a full mediator. The results suggest that higher levels of EO not only have a direct positive effect on OI but also contribute to the development of ACAP, which in turn positively influences OI. Therefore, the majority of the effect of EO on OI can be explained by ACAP. The total effect of EO on OI is (β = 0.635, p<0.001). These findings align with the results of Aljanabi (2018), who found that ACAP partially mediates the relationship between EO and innovation capacities in industrial SMEs. Similarly, the results support the conclusions of Hernández-Perlines and Xu (2018) regarding Spanish family enterprises and Jasimuddin and Naqshbandi (2019) regarding the partial mediating role of ACAP between knowledge infrastructure and OI. The findings also align with the results of Al Mamun et al. (2019) in the context of SMEs in Malaysia, where ACAP played a partial mediating role between EO and innovation.

Furthermore, when evaluating the magnitude of the indirect effect using the variance accounting for formula, an explained variance of 0.815 was obtained. This indicates that the ACAP variable played a mediating role between EO and OI in the research model, as 81.5% of the effect of EO on OI is explained through the mediation of ACAP. The high level of explained variance (greater than 80%) suggests full mediation (Hair et al., 2017), as indicated by the VAF result. Additionally, since the direct impact of EO on OI was not found to be significant, and a significant indirect effect was observed, it provides support for full mediation according to Zhao et al. (2010). Therefore, H4 is supported.

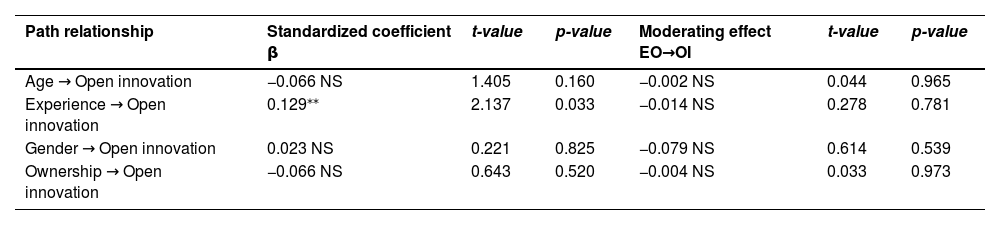

On the other hand, to account for the influence of control variables on open innovation, the structural model was examined by incorporating firm age, ownership type, entrepreneur experience, and gender into the structural model. The analysis revealed that firm age, gender of the executive manager, and ownership type did not have a significant impact on OI. However, entrepreneur experience showed a significant positive influence on OI (β = 0.129, p<0.05). Furthermore, none of the control variables had a significant moderating effect on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and OI, as depicted in Table 7. Nevertheless, the findings indicated that as the company's age decreases, the relationship between EO and OI strengthens. This implies that younger companies may have a greater ability to leverage EO for driving OI. Thus, managers of young firms should be encouraged to embrace an entrepreneurial mindset and actively pursue open innovation practices to capitalize on their inherent advantages.

Moderating effects of the control variables in the structural model with PLS-SEM.

| Path relationship | Standardized coefficient β | t-value | p-value | Moderating effect EO→OI | t-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age → Open innovation | −0.066 NS | 1.405 | 0.160 | −0.002 NS | 0.044 | 0.965 |

| Experience → Open innovation | 0.129⁎⁎ | 2.137 | 0.033 | −0.014 NS | 0.278 | 0.781 |

| Gender → Open innovation | 0.023 NS | 0.221 | 0.825 | −0.079 NS | 0.614 | 0.539 |

| Ownership → Open innovation | −0.066 NS | 0.643 | 0.520 | −0.004 NS | 0.033 | 0.973 |

Significance: *** p<0.001; ** p<0.05; * p<0.1; NS = Non-significant.

Source: Own calculation based on results obtained with SmartPLS 4. Ringle et al. (2022).

Similarly, as company managers gain more experience, this relationship also improves. This suggests that entrepreneurs with more experience are more likely to foster and facilitate OI within their organizations. Therefore, managers and decision-makers should recognize the value of experienced entrepreneurs and consider their expertise when formulating strategies and promoting innovation.

Additionally, non-family companies tend to have a higher ratio of EO to OI. This suggests that non-family businesses may be more inclined to embrace entrepreneurial behaviors and engage in open innovation initiatives. Managers should consider the ownership structure when assessing their organization's innovation capabilities and encourage a culture that fosters entrepreneurial behavior in both family and non-family firms.

Finally, it is worth noting that having a woman in a leadership position generally leads to a better ratio of EO to OI. This finding highlights the positive influence of gender diversity in fostering entrepreneurial orientation and promoting open innovation within organizations. Managers and decision-makers should actively strive to cultivate gender diversity within their organizations to harness the potential benefits it offers in driving innovation and creating a conducive environment for open collaboration.

These findings underscore the importance of considering various factors, including company age, managerial experience, ownership structure (family vs. non-family), and gender of the leader, as they can significantly impact the relationship between EO and OI. Understanding and leveraging these factors can enable organizations to optimize their entrepreneurial orientation and enhance their open innovation practices.

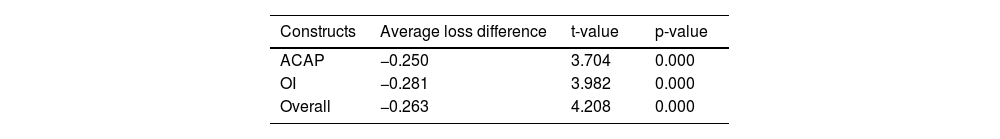

The predictive power of the modelFurthermore, a novel analysis was conducted to evaluate and validate the predictive capabilities of the research model. The cross-validated predictive ability test, developed by Liengaard et al. (2021), was performed as an alternative to PLSpredict for prediction-oriented model comparison in PLS-SEM. This test is recommended for assessing PLS-SEM results (Hair et al., 2022).

In the evaluation of the prediction-based model, the average loss value was compared to the average loss value obtained using the indicator's average (IA) as a naive benchmark, and the average loss value of a linear model (LM) prediction as a more conservative benchmark. The PLS-SEM average loss should be lower than the average loss of the benchmark values, indicated by a negative difference in the average loss values. CVPAT examines whether the average PLS-SEM loss is significantly lower than the average loss of the benchmarks.

In this research, the difference in the average loss values is significantly below zero, as shown in Table 8. This indicates that the research model, compared to the prediction benchmarks, demonstrates superior predictive capability (Hair et al., 2022).

CVPAT – PLS-SEM vs indicator average (IA).

| Constructs | Average loss difference | t-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACAP | −0.250 | 3.704 | 0.000 |

| OI | −0.281 | 3.982 | 0.000 |

| Overall | −0.263 | 4.208 | 0.000 |

Source: Own calculation based on results obtained with SmartPLS 4. Ringle et al. (2022).

The results of this study confirm that ACAP has a direct impact on the open innovation of micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises, while entrepreneurial orientation has an indirect impact on OI through the mediating role of ACAP. The findings support the first hypothesis, indicating that ACAP enhances an enterprise's ability to absorb and apply knowledge, take risks, and capitalize on market opportunities through new products or services, aligning with previous literature (Chesbrough, 2003; Schueffel, 2014; Zhai et al., 2018). One of the significant contributions of this study is validating the role of EO and ACAP as drivers of innovation in enterprises.

Regarding the second hypothesis, the results provide evidence for the relationship between EO and OI, as demonstrated by the significant total effect in the model. The literature has emphasized the importance of EO in fostering OI in enterprises (Carvalho & Sugano, 2016; De Cleyn et al., 2013; Hossain, 2013; Hung & Chiang, 2010). The direct effect of EO positively influences OI, indicating that the ability to innovate, be proactive, and take bold actions to seize business opportunities impacts the flexibility, reflexivity, and outward focus during the innovation process (Mirza et al., 2022). This study aligns with the work of Ingram et al. (2022), emphasizing the strategic position and incentives of EO in driving innovation.

The results support the third hypothesis, indicating a positive and significant relationship between the abilities to acquire, assimilate, transform, and exploit knowledge in relation to ACAP and open innovation. This finding underscores the importance of knowledge exploitation in fostering innovation flexibility. The existing literature has long emphasized the relationship between EO and innovation, highlighting the role of EO in promoting creative mindsets, novel experiences, and innovative ideas to address market challenges (Alegre & Chiva, 2013; Kollmann & Stöckmann, 2014; S.-T. Wang & Juan, 2016). Nevertheless, the competitive global landscape requires a new approach to innovation that leverages external knowledge to inform firms' decision-making processes (Cepeda-Carrion et al., 2023). As various authors have demonstrated, open innovation creates value by encouraging enterprises to explore new avenues for innovation beyond their organizational boundaries (Jasimuddin & Naqshbandi, 2019; Schueffel, 2014).

One notable finding of the study contributes to the theoretical discussion regarding the significance of the firm owners' experience. This finding aligns with the study conducted by Nobakht et al. (2020). Additionally, moderator effects were identified in the relationship between EO and OI. These findings have theoretical implications for understanding the perceptions of MSME owners and their openness to adopting innovative practices from an entrepreneurial standpoint. The results of our study aimed to examine whether the renewal of an enterprise's knowledge base leads to innovation outcomes, supporting the findings of Najar and Dhaouadi (2020) who have emphasized the importance of the open innovation perspective within the framework of resource-based view and knowledge-based view (KBV) to enhance the robustness of the tested relationship.

ConclusionsTheoretical implicationsOur research provides a comprehensive analysis of the impact of EO and ACAP on the OI of micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises. The theoretical framework of our study is grounded in Mintzberg's (1973) theory, which suggests that enterprises tend to exhibit proactive behavior in uncertain environments. Consistent with prior studies, our findings highlight the significance of being proactive and willing to take risks as key predictors of innovation in enterprises (Carvalho & Sugano, 2016; De Cleyn et al., 2013; Hossain, 2013; Hung & Chiang, 2010).

Furthermore, our study examines the direct and mediating effects of absorptive capacity, emphasizing that EO should be accompanied by activities that facilitate knowledge acquisition, transformation, and exploitation to enhance the effectiveness of open innovation. These findings offer valuable insights for enterprise executives. In today's dynamic and uncertain global market, adopting an entrepreneurship-based strategic orientation becomes crucial for making informed decisions about engaging in innovative activities. By promoting actions that foster flexibility, outward focus, and reflexivity, enterprises can enhance their effectiveness and align their efforts with the demands of the market.

Overall, our research contributes to the existing body of knowledge by providing practical implications for enterprise executives seeking to foster innovation and navigate the challenges of an ever-changing business landscape.

Practical implicationsOur study provides valuable empirical evidence on the mediating effect of ACAP, which we found to be a full mediating effect. This finding is in line with previous research that has explored the role of ACAP in enhancing the efficiency of innovation practices (Ahn et al., 2016; Escribano et al., 2009). There has been a growing interest among experts in understanding how ACAP contributes to strategic capabilities, particularly in terms of identifying business opportunities and making informed decisions regarding the allocation of resources and the management of risks (Al Mamun et al., 2019; Hernández-Perlines et al., 2017).

Building upon the work of Zou et al. (2018), Naqshbandi (2016), and Naqshbandi and Kamel (2017), our study highlights the positive and direct causal relationship between EO and ACAP when it comes to leveraging knowledge for enterprise development. This finding has important managerial implications for knowledge management and the mechanisms employed to reduce the uncertainties associated with capitalizing on business opportunities. It emphasizes the importance of extending the boundaries of new ideas and involving all stakeholders in the innovation process.

By shedding light on the interplay between EO, ACAP, and OI, our study offers valuable insights for practitioners seeking to enhance their innovation capabilities and effectively exploit external knowledge. It underscores the importance of fostering a culture of continuous learning, knowledge acquisition, and knowledge utilization to drive innovation and achieve sustainable competitive advantages.

Limitations and future research directionsHowever, like any empirical study, our research has certain limitations that point to potential directions for future research. First, the study's limitation lies in the small sample size, which hinders the generalizability of the findings. Conducting the study with a larger and more diverse sample, and replicating this study in other countries, would contribute to enhancing the external validity of the results.

Another issue is the limited number of studies exploring the relationship between EO, ACAP, and OI, which restricts the general understanding of these dynamics across different contexts. It is recommended that future studies delve deeper into the relationships proposed in our model, exploring diverse industry sectors and geographical locations to obtain a more comprehensive understanding. Additionally, this study is cross-sectional, capturing data at a single point in time. Future research could employ a longitudinal design to investigate how innovativeness, proactivity, and risk-taking contribute to the development of ACAP over time, resulting in a stronger impact on OI.

Furthermore, our study focused solely on micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises in Bogota, excluding larger enterprises and those from other regions of Colombia. Future studies should consider enterprises of various sizes and from different regions, employing a multi-group analysis to assess whether the relationships under study vary across different contexts. This would also help determine if enterprise size acts as a moderator in the relationships and verify the generalizability of the main effects of the variables in the model.

Lastly, we suggest exploring how EO influences frugal innovation when mediated by ACAP and investigating the extent to which OI is enhanced when transformational leadership impacts ACAP. Additionally, examining the impact of OI on technological innovation, performance, and customer satisfaction would provide valuable insights into the broader outcomes of OI for enterprises.

Addressing these limitations would enrich the existing literature and further enhance our understanding of the complex relationships between EO, ACAP, and OI in different organizational contexts.

| Entrepreneurial orientation variable |

| Innovativeness |

| In general, the top managers of my firm favor… |

| OEIN1: A strong emphasis on R&D, technological leadership, and innovations has been favored in the last three years. |

| OEIN2: New product lines or services have been commercialized in the last three years. |

| OEIN3: Significant changes in products or services lines have been quite dramatic in the last three years. |

| Proactivity |

| In dealing with its competitors, our firm… |

| OEP1: Typically initiates actions to which competitors then respond to. |

| OEP2: Is very often the first business to introduce new products or services, administrative techniques, operating technologies, etc. |

| OEP3: Typically adopts a very competitive “undo-the competitors” posture. |

| Risk-taking |

| In general, the top managers of our firm believe that… |

| OER1: Our firm has a strong proclivity for high-risk projects with chances of very high returns. |

| OER2: Our firm, owing to the nature of the environment, bold, wide-ranging acts are necessary to achieve the firm's objectives. |

| OER3: When confronted with decision-making situations involving uncertainty, our firm typically adopts a bold, aggressive posture to maximize the likelihood of exploiting potential opportunities to the fullest extent. |

| NOTE: The variables were measured with a five-point Likert-type scale where 1= completely disagree, 5= completely agree |

| Absorptive capacity (ACAP) variable |

| Acquisition |

| To what extent your company uses external resources to obtain information: |

| AC1: The search for relevant information concerning our industry is every-day business in our company. |

| AC2: Our management motivates the employees to use information sources within our industry. |

| AC3: Our management expects that the employees deal with information beyond our industry. |

| AssimilationTo what extent the following statements fit the communication structure in your organization: |

| AS1: In our company ideas and concepts are communicated cross-departmental. |

| AS2: Our management emphasizes cross-departmental support to solve problems. |

| AS3: In our company there is a quick information flow, e.g., if a business unit obtains important information it communicates this information promptly to all other business units or departments. |

| AS4: Our management demands periodical cross-departmental meetings to interchange new developments, problems, and achievements. |

| Transformation |

| To what extent the following statements fit the knowledge processing in your organization: |

| TR1: Our employees have the ability to structure and to use collected knowledge. |

| TR2: Our employees are used to absorb new knowledge as well as to prepare it for further purposes and to make it available. |

| TR3: Our employees successfully link existing knowledge with new insights. |

| TR4: Our employees are able to apply new knowledge in their practical work. |

| Exploitation |

| To what extent the following statements fit the commercial exploitation of new knowledge in your organization: |

| EX1: Our management supports the development of prototypes. |

| EX2: Our company regularly reconsiders technologies and adapts them accordant to new knowledge. |

| EX3: Our company has the ability to work more effective by adopting new technologies. |

| NOTE: The variables were measured with a five-point Likert-type scale where 1= completely disagree, 5= completely agree |

| Open innovation variable |

| Innovation and flexibility |

| To what extent your company implements the following activities… |

| IF1: New ideas are readily accepted here. |

| IF2: This organization is quick to respond when changes need to be made. |

| IF3: Management here are quick to spot the need to do things differently. |

| IF4: This organization is very flexible; it can quickly change procedures to meet new conditions and solve new problems as they arise. |

| IF5: Assistance in developing new ideas is readily available. |

| IF6: People in this organization are always searching for new ways of looking at problems. |

| Outward focus |

| To what extent your company implements the following activities… |

| OF1: This organization is quite external; it always worries about what is happening in the marketplace. |

| OF2: Ways of improving service to the customer are given much thought. |

| OF3: Customer needs are considered top priority here. |

| OF4: This company is fast to respond to the needs of the customer. |

| OF5: This organization is continually looking for new opportunities in the marketplace. |

| OF6: This organization has the facility to incorporate ideas coming from outside the organization. |

| Reflexivity |

| To what extent your company implements the following activities… |

| RE1: In this organization, the way people work together is readily changed in order to improve performance. |

| RE2: The methods used by this organization to get the job done are often discussed. |

| RE3: There are regular discussions as to whether people in the organization are working effectively together. |

| RE4: In this organization, objectives are modified in light of changing circumstances. |

| RE5: In this organization, time is taken to review organizational objectives. |

| NOTE: The variables were measured with a five-point Likert-type scale where 1= completely disagree, 5= completely agree |