Editado por: Sascha Kraus, Alberto Ferraris, Alberto Bertello

Última actualización: Agosto 2022

Más datosContinuous technological advancements and digitalization are transforming organizations’ resources and capabilities, yet many have not adapted their corporate culture accordingly. Aligning with a digital-oriented culture archetype is crucial for successful digital transformation. This paper presents a research model that predicts digital culture in organizations based on traditional culture archetypes. Using cutting-edge multivariate analysis techniques, such as PLS-SEM, IPMA, or PLS-Predict, on a sample of 285 managers from Spanish companies, the results indicate that a People-oriented culture archetype is the most important for digital culture, while values inherent to Norms or Goals culture archetypes hinder it. The paper contributes to the development of Functionalist and Structuralist Theories of culture, demonstrating the interplay of micro-cultures and cultural archetypes within an organization.

Digitalization is revolutionizing the working environment, and its impact has been accelerated by Industry 4.0, the Internet of Things, and the COVID-19 pandemic (Kraus et al., 2022; Orero-Blat et al., 2022; Dąbrowska et al., 2022). Digital transformation has become an absolute necessity (Kraus et al., 2021; 2022) that disrupts traditional workplaces and labor processes (Kudyba et al., 2020; Bresciani et al., 2021a; Schäfer et al., 2023). The labor market is undergoing significant changes, with machines and algorithms replacing manual mechanisms and human labor (Chen et al., 2022). Companies are making substantial investments in digital transformation initiatives, yet many fail to achieve the desired outcomes (Tabrizi et al., 2019). This can be attributed to a lack of alignment with the company's culture, which necessitates a comprehensive diagnosis and adjustment before implementing technological tools. This perspective is consistent with Andriole (2020, p. 15), who asserts that “digital transformation requires more than upgrading technology or redesigning products”. Therefore, the success of digital transformation hinges on a profound understanding of the organization's culture, as emphasized by Andriole (2020) and Pedersen (2022).

In this context, Western companies, including Renault, Apple, Google, and Nestlé, have wholeheartedly adopted a digital culture marked by risk-taking, innovation, and collaboration (Kane et al., 2018; Grover et al., 2022) as a response to the surge in digitization, encompassing Artificial Intelligence, Big Data Analytics, the Internet of Things, and other related advancements. However, despite this paradigm shift, the theoretical understanding and measurement of digital culture, as well as frameworks for its transformation and change, continue to be underdeveloped areas warranting further research.

Organizational culture is characterized by the perpetual need to adapt to a dynamic technological landscape and generate value changes to meet or anticipate the future demands of this environment. Simultaneously, organizations must uphold stable values and preserve their cultural identity, ensuring the continuity of critical strategic behaviors, key functions, and operational routines (Schein, 1985; Leal-Millán, 1991). Consequently, alongside the persistent values and operational routines maintained over time, there must exist diverse and varied values and change-oriented behaviors that facilitate the development of cultural learning processes (Fiol, 2001). In other words, a certain degree of cultural ambidexterity is required. However, the cultural adaptation/innovation to the environment (exploration) and the reproduction/continuity of culture through the optimization achieved by incorporating or integrating new cultural values (exploitation) represent distinct modes of organizational development guided by different logics (March, 1991).

The process of organizational change or cultural transition, involving the internalization of new values (e.g., digitalization), is contingent upon two key factors. Firstly, it relies on the exploratory endeavor to identify emerging change trends in the environment and assess their significance or impact on survival. Secondly, it hinges on the degree of congruence or conflict with existing organizational values that either facilitate or hinder the integration of these new values into the cultural code—an exploitative effort (Dyer, 1985).

While organizations typically exhibit a dominant cultural archetype that defines their identity, it is important to note that organizational cultures are not monolithic entities. Within them, multiple microcultures coexist, maintaining a delicate balance of power between dominant and competing values (Leal-Millán, 1991). Thus, building upon the insights of Dyer (1985), it becomes evident that the presence of specific archetypes of values deeply entrenched within the organizational culture can either impede or facilitate (prescribe) the implementation of a digital corporate culture.

Specifically, this study seeks to address two research questions: (1) Can digital culture be predicted based on traditional organizational culture archetypes? (2) Which combination of cultural archetypes and values yields the most accurate prediction of digital culture?

There are two prominent theoretical approaches in the conceptualization of organizational culture (Burrell & Morgan, 1979): (i) the functionalist theory, which primarily focuses on exploration, and (ii) the structuralist theory, which incorporates an exploitative perspective of culture. Both approaches highlight the significance of comprehending social structures and their influence on human behavior, albeit from different angles. In this paper, we adopt Quinn and Rohrbaugh's (1981) competing values framework, which integrates both theoretical streams, i.e., functionalist theory and structuralist theory, by proposing the existence of four distinct cultural archetypes.

According to functionalist theory, social institutions exist to fulfill vital social roles, including meeting essential human needs and promoting social stability. This perspective aligns with Quinn and Rohrbaugh's (1981) assertion that cultural systems serve a purpose within organizations. Conversely, structuralist theory focuses on how social institutions establish and maintain power relations in society. This viewpoint is also consistent with Quinn and Rohrbaugh's (1981) theory that cultural systems can be utilized to uphold established social norms and power structures. Structuralist theory examines how the formal structure of an organization influences its performance and behavior, contending that the organization's structure can impact the effectiveness of communication and decision-making processes. The similarities between structuralist theory, functionalist theory, and Quinn and Rohrbaugh's classic cultural archetypes lie in their emphasis on the role of social institutions in shaping individual behavior and societal functioning. Consequently, combining these theories can provide a more comprehensive understanding of organizational dynamics. Each theory offers a unique yet complementary perspective on how organizations can be managed and developed.

The institutionalist approach posits that cultural change is primarily driven by environmental factors or pressures, such as the introduction of new techniques or technologies (e.g., digitalization). While some organizations may adapt to these changes, others may lag behind (Malinowski, 1945). This perspective recognizes the influential role of cultural values and beliefs in regulating behavior, with the notion that ‘function makes the organ’. In contrast, structuralism perceives cultural change as a consequence of conflict between micro-cultures and internal contradictions, placing significant emphasis on analyzing power relations to comprehend cultural change (Giddens, 1984). Within the structuralist paradigm, the debate revolves around the interaction of various social forces and the underlying cultural archetypes.

In this study, we investigate the relationship between organizational culture and the digital landscape using a novel theoretical framework of paradigms interplay (Schultz & Hatch, 1996). Hence, we propose a research model to predict digital culture in organizations based on Quinn and Rohrbaugh's (1981) traditional organizational culture archetypes. In other words, digital culture can also be influenced by internal sociocultural factors (Allaire & Firsirotu, 1984). For instance, certain cultural archetypes may exert positive or synergistic influences, while others may act as barriers or have negative effects within the cultural structure.

To achieve this objective, we conducted a study employing Quinn and Rohrbaugh's (1981) traditional culture archetypes, as defined by the Competing Values Framework (CVF), to predict digital culture in organizations. Our analysis involved a sample of 285 Spanish managers and utilized state-of-the-art multivariate techniques, including partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) and importance-performance map analysis (IPMA). The results revealed that the people-oriented culture emerged as the most significant predictor of digital culture. Furthermore, our findings indicate that successful digitalization necessitates the promotion of values such as closeness, commitment, generosity, loyalty, teamwork, and trust, which are inherent to the people-oriented archetype. Conversely, values associated with norms-oriented and goals-oriented cultures were found to impede digital culture adoption.

This paper contributes to theoretical understanding in three significant ways. Firstly, it integrates functionalist and structuralist perspectives on organizational culture. While previous studies have explored external factors influencing organizational culture (Kirkman et al., 2006; Hofstede, 1990; Hofstede et al., 1990), limited attention has been given to internal influences, specifically the interplay between cultural archetypes within an organization. Secondly, we expand upon the structuralist theory of cultural change proposed by Dyer (1985) and Wilkins and Dyer (1988) by introducing a framework that examines the role of dominant cultural archetypes in shaping and transitioning towards digital culture. Thirdly, our research focuses on measuring culture through archetypes (Richter et al., 2016; Grover et al., 2022), rather than discrete variables or values, which enhances our understanding of digital culture. The implications of our findings extend to the broader field of organizational culture and its relationship with information technology (Leidner & Kayworth, 2006).

Theoretical background and conceptual modelThe mapping of paradigms in organization theory was conducted by Burrell and Morgan (1979), who identified four major paradigms in the field of organizational sociology: functionalist, interpretive, humanist, and structuralist. Over time, these paradigms have evolved, with new ideas and theories emerging to expand upon them (Ooi, 2015). However, the relevance of functionalism and structuralism endures, as their theoretical frameworks on societal and organizational functioning continue to support many contemporary sociological approaches. Therefore, this paper undertakes a literature review on organizational culture and digitalization, and presents a theoretical model that combines functionalism and structuralism as paradigms for our study. Functionalism holds a dominant position in organizational theory (Gioia & Pitre, 1990), while structuralism offers a counter perspective to functionalist assumptions and has gained attention in innovation and change studies (Burrell & Morgan, 1979; Drazin, 1990). These approaches differ in their analytical focus, with functionalism emphasizing causality and structuralism emphasizing association and influence (Hughes & Lambert, 1984). To examine the flow and exchange of cultural influence between internal and external dimensions and organizational archetypes, our research employs a multi-paradigmatic approach (Schultz & Hatch, 1996) that combines these perspectives (Hughes & Lambert, 1984).

The functionalist versus structuralist theory of cultureMost authors consider functionalism as the process that gives rise to ‘adaptation’, which refers to the celebrated ‘fit’ between the organization and its environment. According to functionalists, societies (including organizations) are systems in which every component contributes to the creation of the whole. In this sense, cultures play an essential role in organizations. Cultural values serve as the foundation for decision-making and guide human action. Scholars such as G. Hofstede, E. Schein, F. Trompenaars, C. Handy, and T. Peters have extensively explored the role of culture in management from the functionalist perspective (Sułkowski, 2014).

According to Sułkowski (2014), organizational culture is a comprehensive and systemic phenomenon that actually exists. Like any other system, it consists of particular components or subsystems that operate through causal relationships. Organizational culture, therefore, represents one of the subsystems that shape organizations, alongside structure and strategy. The key to effective corporate culture lies in the degree of efficiency with which it is managed.

However, it is simplistic to engage in an artificial debate of confrontation. Reducing organizational culture to a single archetype or limiting it to the contrast between strong and weak, favorable and detrimental cultures, is not a fruitful approach. In contrast, the functionalist perspective emphasizes balance and harmony. A healthy organizational culture should strive for balance and avoid being overly skewed towards one archetype at the expense of others. Therefore, the culture of organizations cannot be treated prescriptively. There is no such thing as a universally better culture. The values that lead one organization to success may hinder another. Even the values that initially contribute to success can eventually impede performance over time. The culture of each organization should be judged, if at all, based on its evolutionary appropriateness (Hampden-Turner & Trompenaars, 2006).

Following Schein (1985), 1996 and Leal-Millán (1991), organizational culture can be defined as the collection of shared or unspoken values, beliefs, and assumptions held by members of a company. Therefore, organizational culture goes beyond the visible or tangible aspects of the organization, such as the mission, vision, and established or espoused values. It encompasses a broad spectrum that includes people's actions, expectations, decisions, interactions within the organization, and the perceptions and beliefs used to respond to the environment (McDermott & O'Dell, 2001). In short, culture serves as a ‘function’.

Structuralism, on the other hand, emphasizes the importance of ‘structure’ rather than ‘function’. Its general aim is to make the order and relationships within a system intelligible. Structuralist theorists argue that cultural systems are structured embodiments of various activities, social conflicts, and moral dilemmas that individuals face in their lives (Mohr, 1998). Since the late 1980s, a new form of structuralism has emerged in organizational theory, expanding on the sociological structural paradigm by conceptualizing social structure as composed of cultural rules, meaning systems, and material resources. This approach unveils the subtleties of overt and covert power. New structuralist empirical research focuses on the concrete manifestations of culture in everyday practice and employs various relational methods to measure the cultural aspects of social structure (Lounsbury & Ventresca, 2003).

Furthermore, one of the most recent developments in structuralism is the theory of ‘cultural cultivation’ proposed by Harrison and Corley (2011). Taking an open systems perspective on culture, these authors provide insights into the components and processes that underpin the interaction and exchange between external (environment) and internal (organizational) cultures. In other words, the boundaries of organizational culture are permeable, and this permeability can greatly benefit the organization when it comes to renewing or changing its cultural resources. This dynamic interaction operates bidirectionally through ‘push’ and ‘pull’ processes, facilitating the exchange of cultural resources across these permeable boundaries. External cultures both constrain and provide resources that shape cultural behaviors within organizations. Building upon the notion that internal cultures can influence external cultures and vice versa, this paper extends Harrison and Corley's (2011) framework to examine cultural exchanges between cultural archetypes and microcultures within an organization. Special attention is given to the ‘cultural cultivation’ between classical cultural archetypes and digital culture.

Digital cultureTo a certain extent, as highlighted by Gere (2009), the organizational culture is becoming increasingly digital to the point where the concept of ‘digital culture’ runs the risk of becoming a tautology. The process of digitalization is causing significant transformations in work practices and organizational management (Hemerling et al., 2018; Nicolás-Agustín et al., 2021). Numerous studies emphasize that successful navigation of the digital transformation journey necessitates the establishment and diffusion of a digital culture throughout the entire company (Hemerling et al., 2018; Loonam et al., 2018; Brunetti et al., 2020). Thus, digital transformation entails a multidimensional process, whereby investing resources and efforts solely in knowledge acquisition and technological tools (Zaoui & Souissi, 2020; Nadkarni & Prügl, 2021) is insufficient. An organization aspiring to thrive in the digital era must foster a learning environment, develop its teams, and above all, cultivate a culture that supports this profound process of change (Kane, 2019; Nicolás-Agustín et al., 2021).

Undoubtedly, investment in technology is indispensable for an organization's digitalization process. However, it is equally crucial to recognize the significance of intangible elements, such as a robust data-driven organizational culture and exceptional human capabilities, in fully realizing the co-creation and innovation potential of digitalization (Bresciani et al., 2021b). Managers must resist the temptation to perceive digitalization and technology implementation as a substitute for a data-driven culture. Although the advanced technologies available today enable significant automation and reduction in human effort required for data incorporation, storage, processing, assessment, and presentation, the professional skills, experience, and intuitive abilities of managers and workers remain vital. This is especially true in accurately uncovering, evaluating, and analyzing insights derived from data, even in highly digitalized contexts (Bresciani et al., 2021b).

What characteristics should a company's culture have in order to successfully meet the challenges posed by the digital era? This key question has been the focus of several studies; however, there are still gaps in determining the pillars that support a digital culture. Drawing on our experience and an exhaustive review of the literature (Martínez-Caro et al., 2020; Nadkarni & Prügl, 2021; Grover et al., 2022; Kraus et al., 2022), this paper aims to identify the main values inherent to digital culture. Therefore, companies with a strong digital culture are characterized by their openness to change and analytical mindset. Moreover, they are typically managed based on cooperation and the willingness of collaborators to share information, resources, and knowledge. Such organizations prioritize adapting to the customer through continuous learning and exhibit tolerance for failure.

Put simply, a digital culture necessitates individuals who are willing to question established routines and the status quo while continuously learning to ensure their knowledge remains relevant in response to evolving market demands. Thus, those immersed in a digital culture must possess not only a comprehension of technological terminology and proficiency in the virtual environment but, above all, the ability to utilize these tools for interaction, collaboration, and knowledge generation. Furthermore, deliberately promoting specific cultural values such as adaptability, experimentation, continuous learning, cooperation—recognizing and incentivizing these qualities—embracing a reasonable level of risk and failure, and increasingly organizing around cross-functional teams are crucial (Kane, 2019).

Traditional management approaches grounded in long-term strategic planning prove ineffective in the digital economy. Consequently, decision-making processes must operate under the premise that the environment is tumultuous and dynamic. Thus, it becomes paramount to base decisions on tools such as experimentation and analysis of the data gathered and generated by the organization. In essence, companies should systematize and amplify data collection and analysis efforts and, consequently, leverage this knowledge to foster an optimized and nimble response (Martínez-Caro et al., 2020).

Furthermore, for any company aspiring to cultivate or adopt a digital culture, prioritizing the training of its human capital becomes imperative (Kane, 2019; Nicolás-Agustín et al., 2021). Through training and socialization, it becomes feasible to disseminate and solidify an organizational culture. According to a prominent report by Randstad Research (2016), the success of companies in implementing a digital transformation process hinges on fostering the growth of cross-functional soft skills among their employees. These skills encompass analytical aptitude, effective communication, team leadership, and proficient problem-solving abilities.

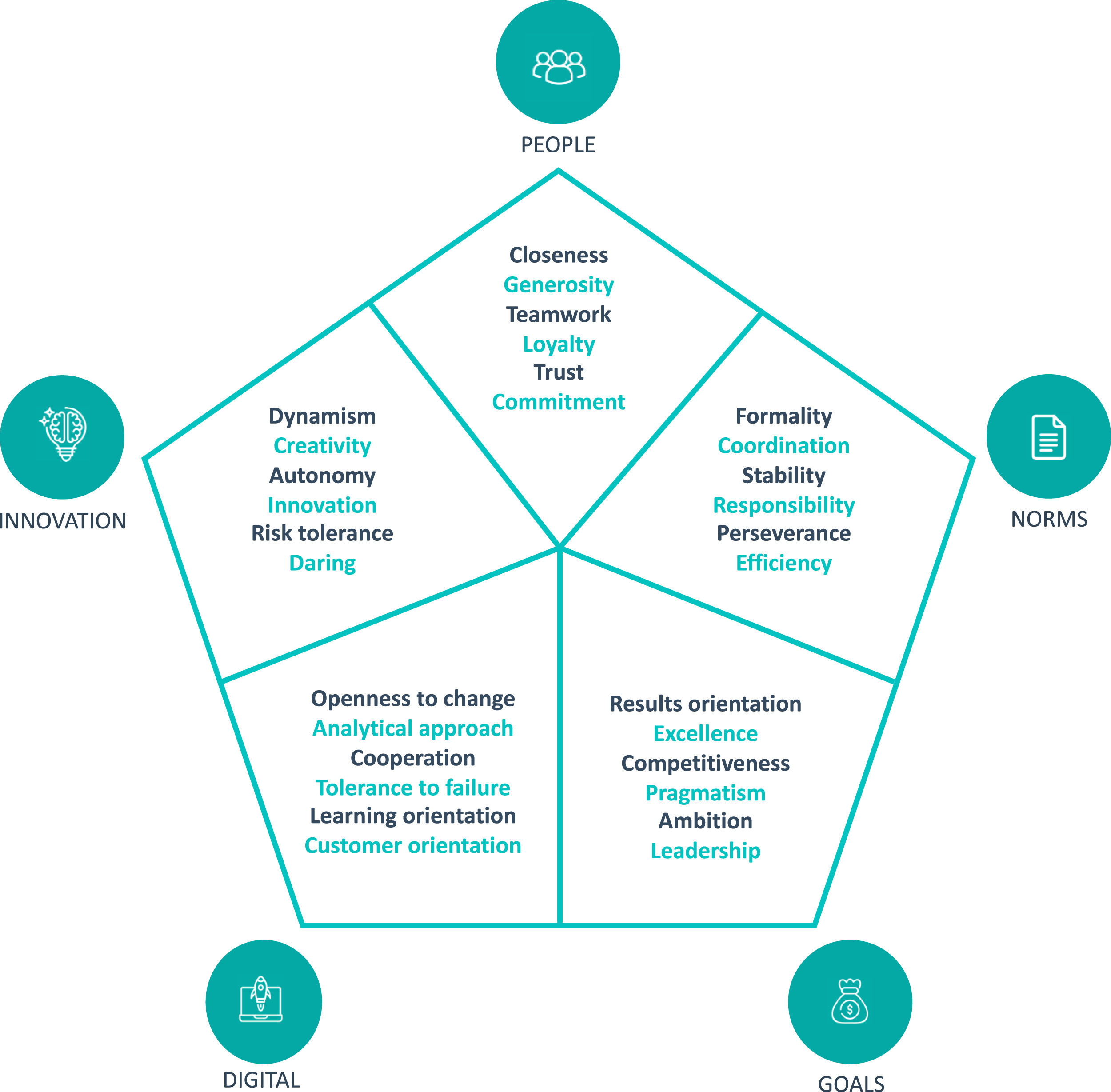

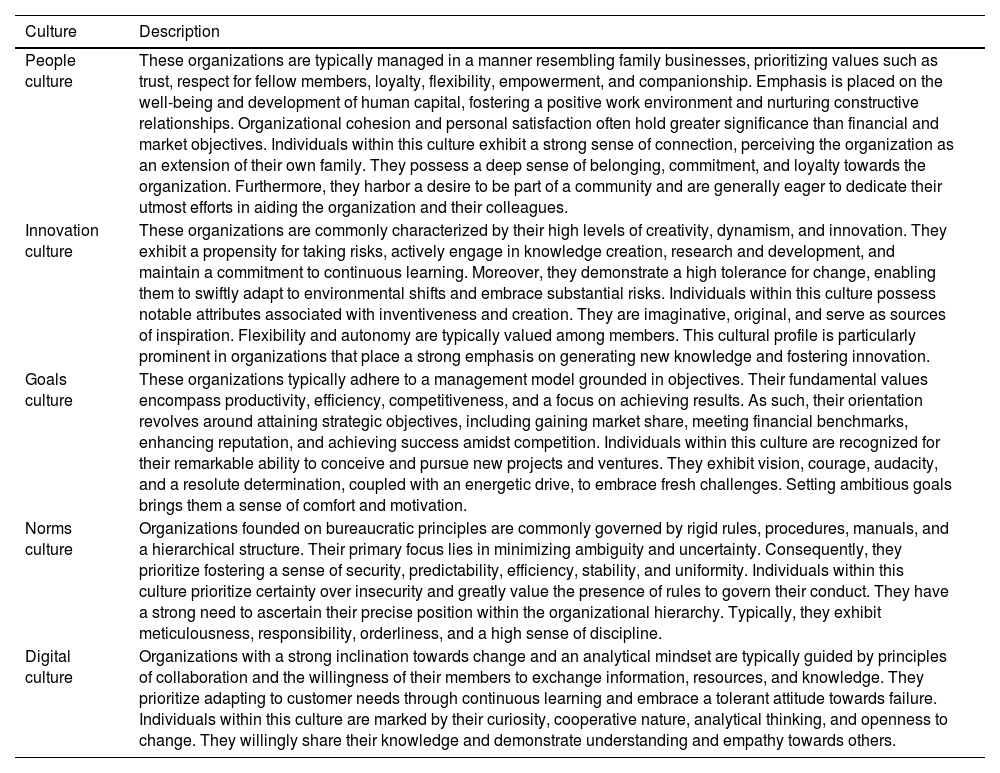

The cultural fit assessment methodThe Cultural Fit Assessment Method (CFAM) has been rigorously developed by Leal-Rodríguez et al. (2023). This method draws inspiration from the Cultural Diagnosis and Change Model, which was formulated by Cameron and Quinn (1999) based on the Competing Values Framework (Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1981). As such, it is a method founded on extensively tested and validated studies endorsed by the academic community. Cameron and Quinn's (1999) model, in particular, boasts over 10,000 citations and has been successfully employed and validated in numerous empirical studies and business consulting projects. The CFAM method consists of a total of 12 questions that facilitate the assessment of the alignment between an organization's culture and that of a specific individual. Specifically, this method delineates five distinct typologies of organizational culture: People, Innovation, Goals, Norms, and Digital (refer to Fig. 1). Furthermore, Table 1 provides a comprehensive description of the values inherent in these five cultural typologies.

Description of cultural archetypes.

| Culture | Description |

|---|---|

| People culture | These organizations are typically managed in a manner resembling family businesses, prioritizing values such as trust, respect for fellow members, loyalty, flexibility, empowerment, and companionship. Emphasis is placed on the well-being and development of human capital, fostering a positive work environment and nurturing constructive relationships. Organizational cohesion and personal satisfaction often hold greater significance than financial and market objectives. Individuals within this culture exhibit a strong sense of connection, perceiving the organization as an extension of their own family. They possess a deep sense of belonging, commitment, and loyalty towards the organization. Furthermore, they harbor a desire to be part of a community and are generally eager to dedicate their utmost efforts in aiding the organization and their colleagues. |

| Innovation culture | These organizations are commonly characterized by their high levels of creativity, dynamism, and innovation. They exhibit a propensity for taking risks, actively engage in knowledge creation, research and development, and maintain a commitment to continuous learning. Moreover, they demonstrate a high tolerance for change, enabling them to swiftly adapt to environmental shifts and embrace substantial risks. Individuals within this culture possess notable attributes associated with inventiveness and creation. They are imaginative, original, and serve as sources of inspiration. Flexibility and autonomy are typically valued among members. This cultural profile is particularly prominent in organizations that place a strong emphasis on generating new knowledge and fostering innovation. |

| Goals culture | These organizations typically adhere to a management model grounded in objectives. Their fundamental values encompass productivity, efficiency, competitiveness, and a focus on achieving results. As such, their orientation revolves around attaining strategic objectives, including gaining market share, meeting financial benchmarks, enhancing reputation, and achieving success amidst competition. Individuals within this culture are recognized for their remarkable ability to conceive and pursue new projects and ventures. They exhibit vision, courage, audacity, and a resolute determination, coupled with an energetic drive, to embrace fresh challenges. Setting ambitious goals brings them a sense of comfort and motivation. |

| Norms culture | Organizations founded on bureaucratic principles are commonly governed by rigid rules, procedures, manuals, and a hierarchical structure. Their primary focus lies in minimizing ambiguity and uncertainty. Consequently, they prioritize fostering a sense of security, predictability, efficiency, stability, and uniformity. Individuals within this culture prioritize certainty over insecurity and greatly value the presence of rules to govern their conduct. They have a strong need to ascertain their precise position within the organizational hierarchy. Typically, they exhibit meticulousness, responsibility, orderliness, and a high sense of discipline. |

| Digital culture | Organizations with a strong inclination towards change and an analytical mindset are typically guided by principles of collaboration and the willingness of their members to exchange information, resources, and knowledge. They prioritize adapting to customer needs through continuous learning and embrace a tolerant attitude towards failure. Individuals within this culture are marked by their curiosity, cooperative nature, analytical thinking, and openness to change. They willingly share their knowledge and demonstrate understanding and empathy towards others. |

Source: own elaboration based on Cameron and Quinn (1999).

New technologies have encouraged organizational digital transformation across all industry sectors. These advancements enable businesses to develop, access, and communicate information resources more efficiently. The incorporation and future demand for an expanding workforce, which includes knowledge workers, as coined by Drucker, have been facilitated by these functional features. However, the mere availability of new technologies and human resources does not guarantee improvements in operational planning, efficiency, and creativity. The interactions between workers and technologies introduce significant complexity and entail challenges that must be acknowledged, understood, and effectively managed (Kudyba et al., 2020). This aligns with the assertion by Bertello et al. (2021) that fostering a data-driven organizational culture requires investments in big data analytics infrastructure along with enhancing managerial capabilities. Therefore, the digitalization process necessitates more than mere technological upgrades or process redesign. Failing to align technological endeavors and investments with employees’ values, beliefs, and behaviors can pose risks to an organization's culture, while a comprehensive and collaborative effort can facilitate cultural change to embrace and drive digital transformation (Andriole, 2020).

Nowadays, few companies would pride themselves on their continuity, sameness, or status quo compared to a decade ago, as noted by Cameron and Quinn (1999). The fear of uncertainty associated with maintaining the status quo has replaced the apprehension once linked to significant transformations (Felipe et al., 2017). In their seminal work, "Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture based on the Competing Values Framework," these authors assert that most organizations struggle to effectively manage change due to inadequate implementation of cultural change. Therefore, this paper argues that fostering a digital culture necessitates the establishment of a foundation based on a series of cultural archetypes and values. Organizational culture typologies have been examined as influential drivers of various critical components of organizational performance, such as total quality management (Roldán et al., 2012), human resource management traits (Acosta-Prado et al., 2020), and innovation outcomes (Leal-Rodríguez et al., 2014), among others. This prompts us to assess its impact on digitalization.

To some extent, the significance of organizational culture (OC) in the achievement of digital transformation or the digitalization process has been suggested (Andriole, 2020; Nadkarni & Prügl, 2021). However, there is a lack of empirical studies aimed at offering explanatory or predictive evidence for these relationships. This study asserts that the four typologies of organizational culture, as defined by the Competing Values Framework (CVF), possess distinct characteristics and specificities that may have varying impacts on digital culture. Moreover, the investigation aims to determine which cultures exert a greater influence on the endogenous construct.

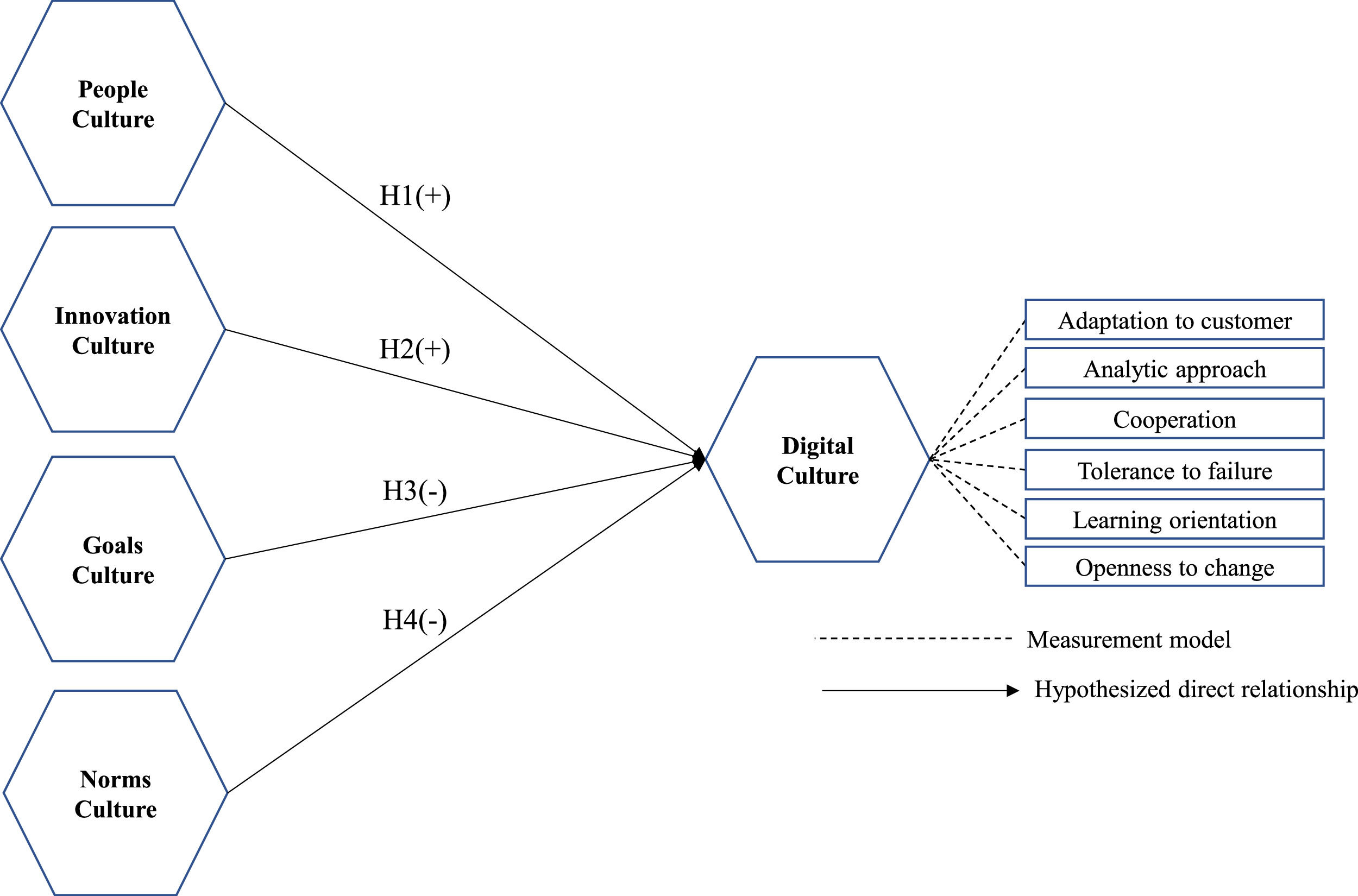

The commitment of firms to the growth and well-being of their human capital is undeniably distinctive to People culture. Such an endeavor can serve as a strong predictor of digital culture as it significantly enhances collaboration bonds among individuals and teams. Specifically, the organization's ability to effectively manage the development, adaptation, dissemination, and utilization of ideas and knowledge within the workplace is crucial for fostering a digital shift (Bresciani et al., 2021b), with People culture playing a significant role in facilitating these processes. Moreover, flatter and more flexible structures that empower autonomous team members, with supervisors acting as facilitators or mentors, are inherent characteristics of People culture, which can potentially contribute to improved digitalization outcomes (Tabrizi et al., 2019; Ghosh et al., 2022). This aligns with the findings of Felipe et al. (2017), who established a positive and statistically significant correlation between Clan culture and organizational agility. Additionally, the results of a Delphi survey conducted by Hartl and Hess (2017), involving 25 research and business experts, suggest that a combination of two culture types from the competing values framework, emphasizing values that promote innovation and care for people, yields optimal outcomes in digitalization. Therefore, this paper posits a positive relationship between People culture and Digital culture (Fig. 2):

Hypothesis 1

(H1). People culture is positively related to Digital culture.

In a recent qualitative study, Warner and Wäger (2019) examined how organizations in traditional industries develop dynamic capabilities for digital transformation. According to the authors, fostering a pro-innovative mindset, which involves practices like quick prototyping, establishing R&D labs, and building lean product development competencies, is essential for successful digital transformation. In essence, organizations aiming to thrive in their digitalization process need to embrace a ‘Silicon Valley startup culture’ characterized by a focus on innovation, rapid prototyping, and agile decision-making. Therefore, an Innovation culture that actively promotes change, adaptation, and innovation can serve as a powerful catalyst for digitalization (Hartl & Hess, 2017), considering the highly unpredictable, ever-changing, and complex business landscape organizations face today. Hence, it is hypothesized that the Innovation culture type exhibits a positive relationship with Digital culture (Fig. 2):

Hypothesis 2

(H2). Innovation culture is positively related to Digital culture.

Due to its outward focus and strong support for strategic planning, management by objectives, and goal-setting procedures, a goals-oriented culture can be perceived as a driver of competitive success. Advocates of this culture argue that clearly defined objectives and an assertive approach lead to increased output and revenue (Grover et al., 2022). However, this clear emphasis on reducing ambiguity through the establishment of comprehensive goals, milestones, and objectives can potentially impede digitalization. This aligns with previous research suggesting that cultural values such as tight deadlines and team efficiency within organizations may hinder processes such as organizational learning or innovation (Sanz-Valle et al., 2011). While these authors found a negative association between the goals-oriented cultural archetype and organizational learning, as well as with innovation, neither of these connections proved statistically significant. According to the authors, the Goals culture's focus on control and stability (rather than flexibility) has a detrimental impact on organizational learning. However, the external focus of this culture may mitigate the negative effect of its orientation towards control and stability. Consequently, this paper hypothesizes that Goals culture will have a negative influence on Digital culture (Fig. 2):

Hypothesis 3

(H3). Goals culture is negatively related to Digital culture.

Finally, Norms culture can be defined as a culture that prioritizes efficiency and internal control. Organizations that adhere to bureaucratic values often employ strict rules, processes, manuals, and a hierarchical structure. The focus is on minimizing ambiguity and confusion while maintaining a sense of security, predictability, efficiency, stability, and uniformity. Individuals who are accustomed to working within a flawless bureaucratic system may struggle to adapt to a digital mindset that requires constant reconfiguration to accommodate technological shifts. In this regard, Sanz-Valle et al. (2011) argue that this culture places significant emphasis on adhering to norms, formal procedures, and control. These factors are perceived as major obstacles to organizational learning as they hinder autonomy, a continuous orientation towards change, communication and dialog, empowerment, and risk-taking. Consequently, these authors found a statistically significant negative correlation between this cultural type and organizational learning in their study. Therefore, it is hypothesized that Norms culture is associated with lower levels of Digital culture (Fig. 2):

Hypothesis 4

(H4). Norms culture is negatively related to Digital culture.

MethodData collection and sampleAs Hulland et al. (2018) point out, surveys remain a relevant method for acquiring new knowledge and insights in social science research. Therefore, this study utilizes survey data to examine the relationships between classic archetypes of organizational culture and digital company culture.

Regarding the sampling procedures, this study employed a non-probability purposive sampling method based on a deductive methodology (Hulland et al., 2018). Non-probabilistic samples, often referred to as targeted or convenience samples, involve a screening process guided by the research's specific characteristics rather than a statistical generalization criterion. Many quantitative and qualitative studies make use of such samples. Given our intention to examine the position and behavior of organizations already undergoing digital transformation, we opted for a convenience sample in this case. Consequently, our target population consisted of managers and staff members working in Spanish firms with over 50 employees and a reasonable level of digitalization. The decision to include not only managers but also other employees is based on the understanding that culture is not something that can be imposed top-down but is rather co-created by all members of the organization. According to the Spanish National Statistics Institute, the target population for this study comprised 2993 companies as of January 2022. Subsequently, in March 2022, we sent a link to an electronic questionnaire via email to 300 firms that met our selection criteria. Following the approach outlined by Baruch and Holtom (2008), cover letters were sent to provide an overview of the study's objectives, data collection methods, and confidentiality regulations. Ultimately, we collected 285 valid responses, resulting in a response rate of 16.6%, from a total of 50 companies.

In this study, data is collected through a gamified self-assessment test embedded in a website belonging to our research group. The data collection process is fully automatic and conducted online. Participants access the web application through a unique URL containing a token that identifies the organization under study in the database. This allows us to gather all the necessary data from the organization for subsequent analysis.

The web application presents several batches of questions, totaling eighteen in number. Each question offers five options related to corporate values, which the user must rank from highest to lowest based on their degree of identification with each value. Following the completion of the questions, an additional form is presented to the respondent to provide personal information. This information is highly valuable and includes details such as the department/area of the company in which they work, level of responsibility, location, gender, etc. These details enable the establishment of different levels of analysis in the subsequent stages of the study.

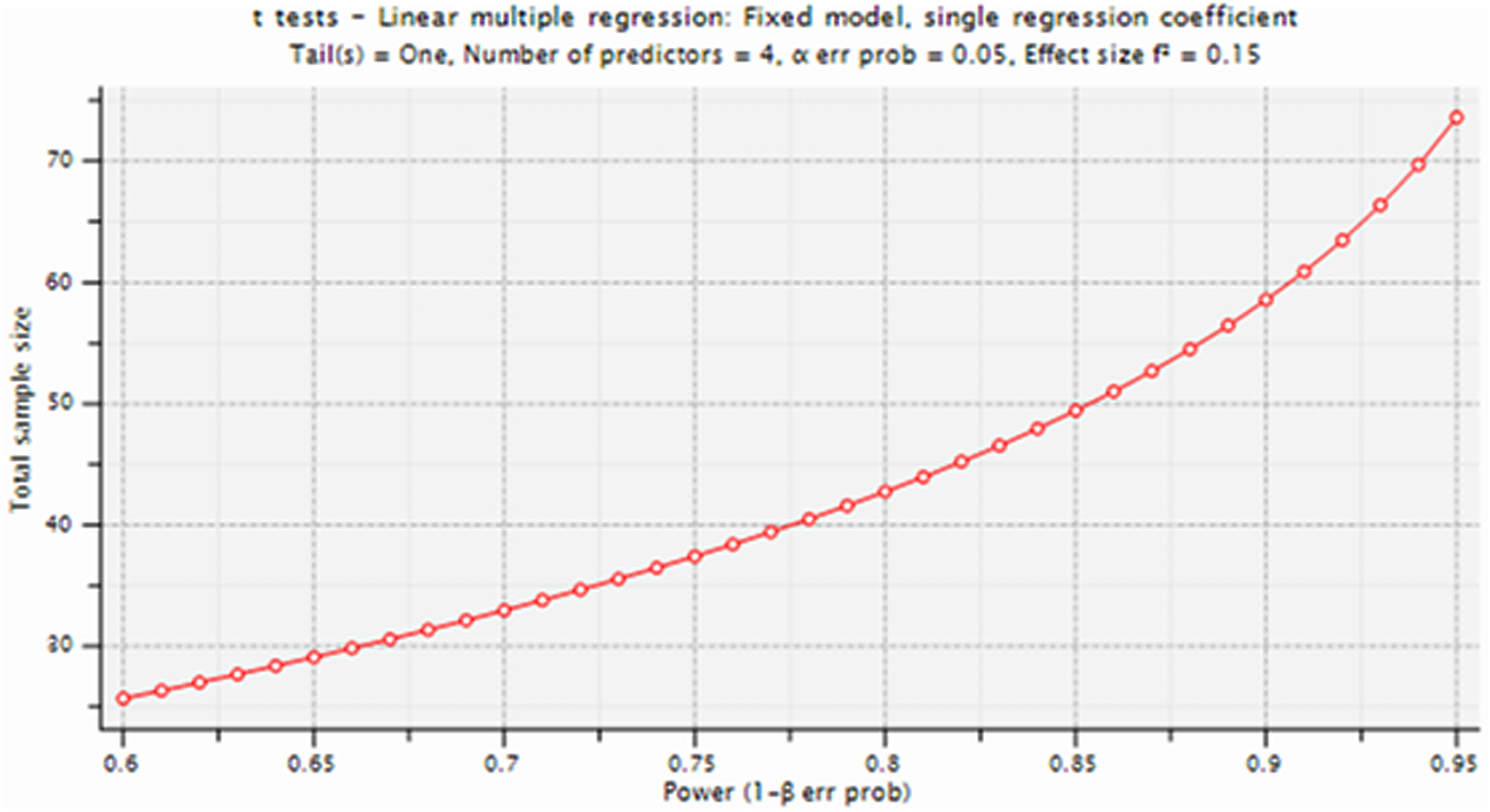

According to Kline (2005), the sample size used in this study, consisting of 285 individuals, would be considered small to medium. To verify the adequacy of the sample size, we conducted an a priori analysis using the Gpower 3.1 tool, as recommended by Faul et al. (2009). This analysis estimates the required sample size based on predetermined values for the desired significance level (α), statistical power (1-β), and population effect size. In our model, which includes four predictors, the Gpower test indicated that a minimum sample size of 74 individuals is needed to achieve a power of 0.95, with an alpha of 0.05 (see Fig. 3). Therefore, our final sample of 285 individuals surpasses the initial sample size requirements (Roldán & Sánchez-Franco, 2012).

Regarding the respondents’ profile, the sample consists of 285 individuals, of which 114 (40%) are male, 81 (28.4%) are female, and 90 (31.6%) preferred not to declare their gender. In terms of managerial level, the 285 respondents are classified as follows: 100 (35%) are first-line managers, 46 (16%) are middle managers, 42 (15%) are senior managers, and 97 (34%) do not have personnel under their supervision.

MeasuresThis section aims to elucidate the procedures employed to accomplish the goal of developing and validating a measurement instrument for the digital culture construct. In this study, an adaptation of the Organizational Culture Assessment Instrument (OCAI) was utilized, which has been previously employed and validated for assessing the classic cultural archetypes formulated by Cameron and Quinn (1999) and derived from the Competing Values Framework (Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1981). These archetypes include Clan (also referred to as People) culture, Adhocracy (also known as Innovation) culture, Market (also termed Goals) culture, and Hierarchy (also denoted as Norms) culture. Additionally, the endogenous construct, Digital culture, was evaluated using a scale developed based on a comprehensive qualitative analysis conducted earlier, also drawing inspiration from the Competing Values Framework.

The authors initiated the process by creating a preliminary set of 26 items that encompassed various aspects of digital culture. This compilation was based on an extensive review of the literature on organizational culture and digitalization, encompassing 262 papers published between 1980 and 2022. To conduct the review, a keyword search was conducted in the Web of Science (WoS) repository, focusing on terms such as "digital culture" (Topic) OR "organizational culture" AND "digital*" (Topic) within the Business Economics research area.

Following the literature review, in-depth interviews were conducted with managers to gain further insights into the cultural factors and drivers of digitalization. These semi-structured interviews involved specialists from academia and industry who have contributed to the ongoing discourse on digitization at the business level. The experts were presented with the five constructs and their definitions and were asked to discuss how they believed these cultural archetypes manifest in an organization, specifically identifying the values, behaviors, or organizational structures associated with the five cultures shaping the model. The interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded, and the findings were combined with the literature review to generate potential new items.

Using the gathered information, a six-item instrument for measuring digital culture was developed, utilizing a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The initial questionnaire draft underwent a proofreading and refinement process by a panel of practitioners and academic experts to ensure contextual and content validity. Minor language adjustments were made based on their feedback. After conducting pilot testing, a comprehensive survey was launched, and the collected data underwent various statistical tests to assess item reliability, composite reliability, convergent validity, discriminant validity, absence of multicollinearity, and other relevant factors.

The initial responses indicated that all the items achieved loadings exceeding the critical threshold of 0.707, thus satisfying the requirement for item reliability. Furthermore, the internal consistency of the constructs under examination ranged from 0.88 (Cronbach's alpha) to 0.91 (composite reliability), surpassing the recommended minimum value of 0.7 as suggested by Hair et al. (2010). Moreover, the average variance extracted surpassed the critical level of 0.5, attaining a value of 0.62, thereby confirming convergent validity.

Lastly, a panel of knowledgeable scholars convened as a Focus group to review a preliminary draft of the instrument. This panel of experts gathered in Toledo, Spain, in February 2022 during the XXXI Iberian Conference on Scientific Management. Their feedback and insights contributed to the final version of the instrument, which comprises 36 items. All items were measured using five-point ordinal scales.

Data analysisThis study employs partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), a variance-based SEM approach (Roldán & Sánchez-Franco, 2012), to test the conceptual model and hypotheses. PLS-SEM is a quantitative method widely used in the social sciences, particularly in management, marketing, and economics (Hair et al., 2012). It is well-suited for exploring relationships between latent constructs such as attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors in complex systems (Hair et al., 2014). The choice of PLS-SEM is motivated by the composite construct nature of the variables in our study model (Benítez-Amado et al., 2017). Previous studies (Henseler et al., 2014; Rigdon, 2012; Rigdon et al., 2017) and empirical simulations (Becker et al., 2013; Sarstedt et al., 2016; Felipe et al., 2020) have supported and praised the use of PLS-SEM for models with composite constructs, highlighting its consistency (Rigdon, 2016) and lack of bias (Sarstedt et al., 2016). Furthermore, this study aims to assess the predictive power of key constructs in relation to digital culture, making PLS-SEM an appropriate method for analysis. The measurement and structural models were estimated using SmartPLS v3.2.9 software (Ringle et al., 2015).

In addition to PLS-SEM, this paper complements the analysis with two advanced techniques: Importance-Performance Map Analysis (IPMA) and PLS-Predict. The combination of these methods enables researchers to gain a deeper understanding of the complex relationships between variables, as well as the relative importance and performance of these variables within a specific context. This integrated approach facilitates a comprehensive analysis of the data, enhancing our understanding of the underlying relationships between variables and their impact on the outcome of interest. The combination of PLS-SEM and IPMA offers valuable insights into the relative importance and performance of variables, while PLS-Predict allows for predictions based on these relationships.

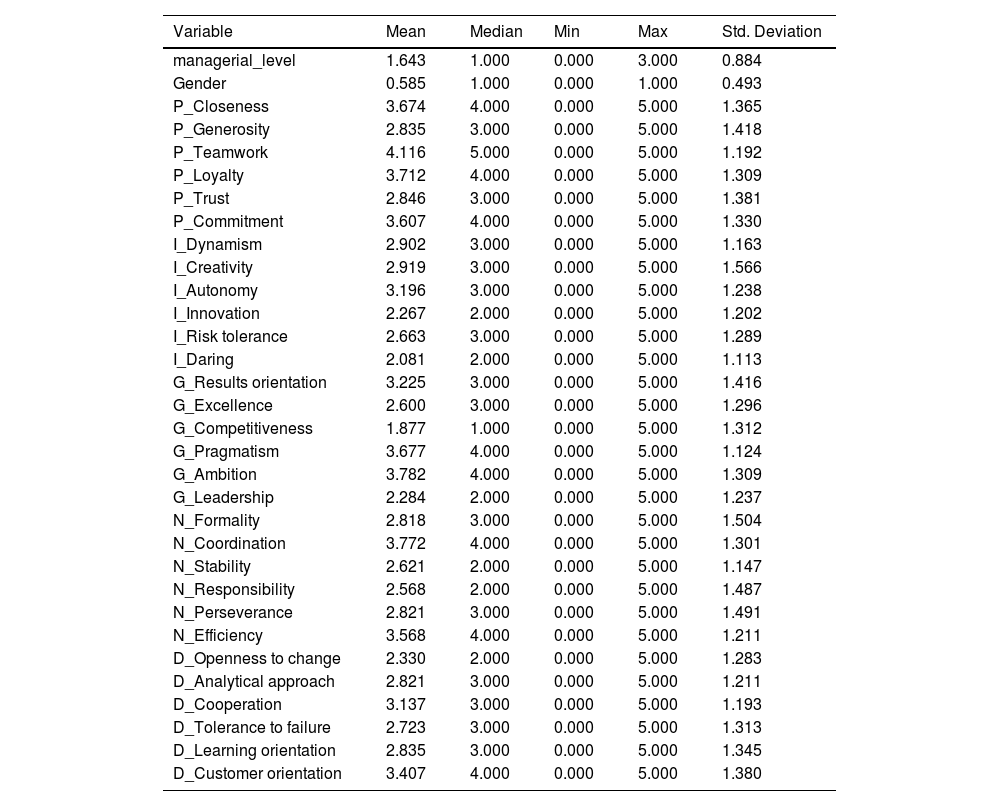

ResultsDescriptive statisticsTable 2 presents descriptive statistics for the manifest variables analyzed in the model. It includes the mean, median, standard deviation, as well as the minimum and maximum values.

Descriptive statistics.

| Variable | Mean | Median | Min | Max | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| managerial_level | 1.643 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 3.000 | 0.884 |

| Gender | 0.585 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.493 |

| P_Closeness | 3.674 | 4.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.365 |

| P_Generosity | 2.835 | 3.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.418 |

| P_Teamwork | 4.116 | 5.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.192 |

| P_Loyalty | 3.712 | 4.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.309 |

| P_Trust | 2.846 | 3.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.381 |

| P_Commitment | 3.607 | 4.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.330 |

| I_Dynamism | 2.902 | 3.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.163 |

| I_Creativity | 2.919 | 3.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.566 |

| I_Autonomy | 3.196 | 3.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.238 |

| I_Innovation | 2.267 | 2.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.202 |

| I_Risk tolerance | 2.663 | 3.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.289 |

| I_Daring | 2.081 | 2.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.113 |

| G_Results orientation | 3.225 | 3.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.416 |

| G_Excellence | 2.600 | 3.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.296 |

| G_Competitiveness | 1.877 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.312 |

| G_Pragmatism | 3.677 | 4.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.124 |

| G_Ambition | 3.782 | 4.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.309 |

| G_Leadership | 2.284 | 2.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.237 |

| N_Formality | 2.818 | 3.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.504 |

| N_Coordination | 3.772 | 4.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.301 |

| N_Stability | 2.621 | 2.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.147 |

| N_Responsibility | 2.568 | 2.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.487 |

| N_Perseverance | 2.821 | 3.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.491 |

| N_Efficiency | 3.568 | 4.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.211 |

| D_Openness to change | 2.330 | 2.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.283 |

| D_Analytical approach | 2.821 | 3.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.211 |

| D_Cooperation | 3.137 | 3.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.193 |

| D_Tolerance to failure | 2.723 | 3.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.313 |

| D_Learning orientation | 2.835 | 3.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.345 |

| D_Customer orientation | 3.407 | 4.000 | 0.000 | 5.000 | 1.380 |

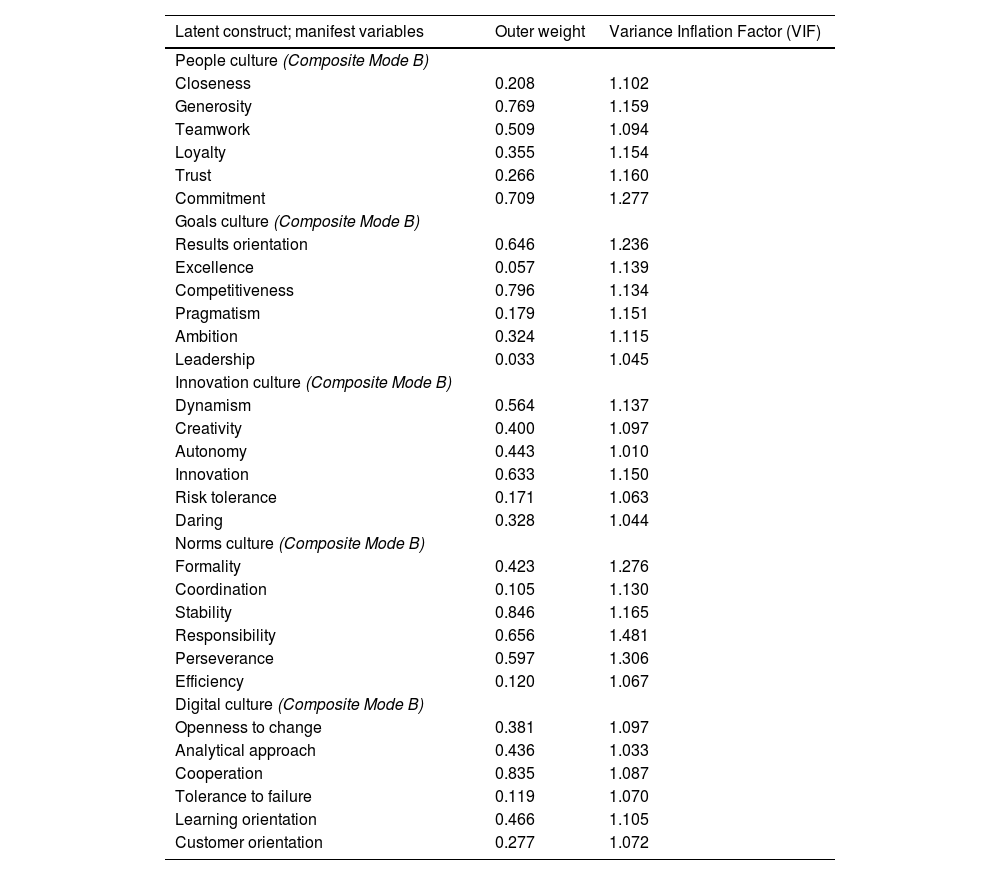

The five cultural typologies in the CFAM model have been estimated as Mode B (formative) composites. This modeling approach aligns with previous studies that also employed Mode B to estimate the cultural archetypes inherent in the OCAI Model (Sanz-Valle et al., 2011; Roldán et al., 2012; Naranjo-Valencia et al., 2017; Felipe et al., 2017). Consequently, these composites require a different evaluation compared to the constructs modeled in Mode A (reflective). Instead of assessing factor loadings and various measures of composite reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity, it is necessary to test for the absence of multicollinearity between the different manifest variables and examine the weights of these indicators in shaping their respective constructs. Concerning multicollinearity between items, Petter, Straub and Rai (2007) suggest that a variance inflation factor (VIF) higher than 3.3 indicates high multicollinearity. In our case, the maximum VIF value for indicators was 1.481, which is well below this critical threshold. Therefore, it can be concluded that the analyzed model does not exhibit any multicollinearity issues. Next, we assessed the magnitude and significance of the weights, as presented in Table 3. These weights provide insights into the contribution of each indicator to its respective composite (Chin, 1998), enabling the classification of indicators based on their contribution.

Measurement model results.

| Latent construct; manifest variables | Outer weight | Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) |

|---|---|---|

| People culture (Composite Mode B) | ||

| Closeness | 0.208 | 1.102 |

| Generosity | 0.769 | 1.159 |

| Teamwork | 0.509 | 1.094 |

| Loyalty | 0.355 | 1.154 |

| Trust | 0.266 | 1.160 |

| Commitment | 0.709 | 1.277 |

| Goals culture (Composite Mode B) | ||

| Results orientation | 0.646 | 1.236 |

| Excellence | 0.057 | 1.139 |

| Competitiveness | 0.796 | 1.134 |

| Pragmatism | 0.179 | 1.151 |

| Ambition | 0.324 | 1.115 |

| Leadership | 0.033 | 1.045 |

| Innovation culture (Composite Mode B) | ||

| Dynamism | 0.564 | 1.137 |

| Creativity | 0.400 | 1.097 |

| Autonomy | 0.443 | 1.010 |

| Innovation | 0.633 | 1.150 |

| Risk tolerance | 0.171 | 1.063 |

| Daring | 0.328 | 1.044 |

| Norms culture (Composite Mode B) | ||

| Formality | 0.423 | 1.276 |

| Coordination | 0.105 | 1.130 |

| Stability | 0.846 | 1.165 |

| Responsibility | 0.656 | 1.481 |

| Perseverance | 0.597 | 1.306 |

| Efficiency | 0.120 | 1.067 |

| Digital culture (Composite Mode B) | ||

| Openness to change | 0.381 | 1.097 |

| Analytical approach | 0.436 | 1.033 |

| Cooperation | 0.835 | 1.087 |

| Tolerance to failure | 0.119 | 1.070 |

| Learning orientation | 0.466 | 1.105 |

| Customer orientation | 0.277 | 1.072 |

To evaluate the structural model, several aspects need to be considered. Firstly, the coefficients of variance explained, also known as the coefficient of determination (R2), for the endogenous variables must be assessed. Secondly, the magnitude of the path coefficients (β) and the strength of these relationships should be evaluated. The significance of these relationships can be analyzed using the Bootstrapping procedure, which involves generating 5000 random samples.

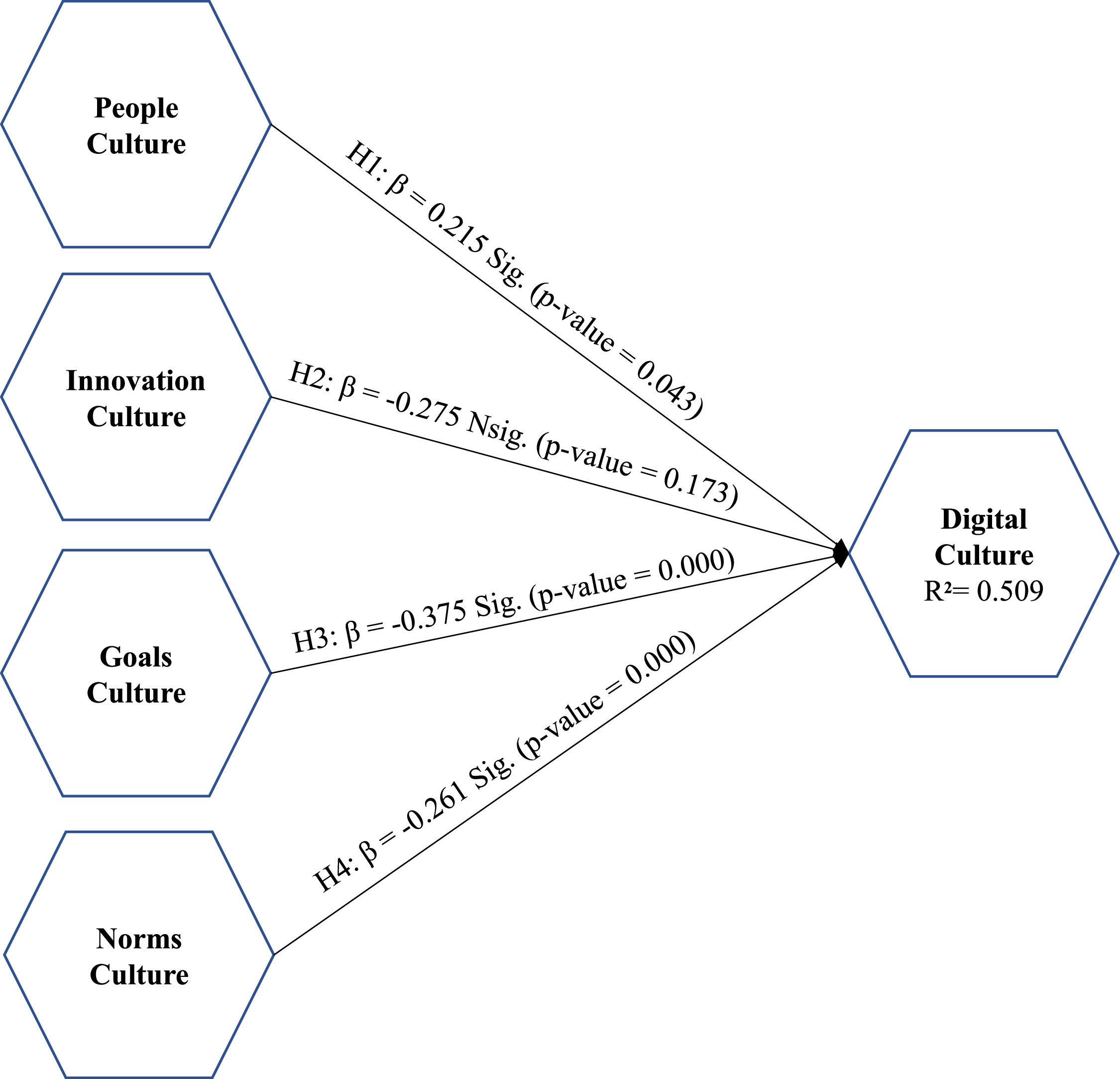

Evaluation of the coefficient of determination (R2)The coefficient of determination (R2) is a measure of the predictive power of a model, indicating the proportion of variance in an endogenous construct explained by its predictor variables. Ranging from 0 to 1, the R2 score reflects the model's ability to predict the variable of interest. It is essential for R2 values to be sufficiently high to demonstrate at least some explanatory power (Urbach & Ahlemann, 2010). However, the appropriate levels of this indicator may vary across disciplines. Falk and Miller (1992) suggest that the explained variance of endogenous variables should be greater than or equal to 0.1, as lower values, despite being statistically significant, provide limited information and have minimal predictive ability. Chin (1998)) categorizes R2 values close to 0.6 as substantial, those close to 0.3 as moderate, and those below 0.2 as weak. Similarly, Hair et al. (2011) describe values above 0.75 as substantial, above 0.5 as moderate, and above 0.25 as weak. In our study, the endogenous construct Digital Culture has an R2 value of 0.509 (refer to Table 4 and Fig. 4), which can be classified as moderate to high. Therefore, we can conclude that the model demonstrates an adequate level of explanatory power based on these values.

Structural model results.

| Relationship | Β | t | p-value | 5% | 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: People culture → Digital culture | 0.215 Sig. | 1.719 | 0.043 | 0.007 | 0.357 |

| H2: Innovation culture → Digital culture | −0.275 Nsig. | 0.944 | 0.173 | −0.466 | 0.244 |

| H3: Goals culture → Digital culture | −0.375 Sig. | 5.469 | 0.000 | −0.490 | −0.270 |

| H4: Norms culture → Digital culture | −0.261 Sig. | 3.736 | 0.000 | −0.341 | −0.149 |

| R2Digital culture = 0.509 |

Note: Sig. = statistically significant relationship; Nsig. = statistically non-significant relationship.

The path coefficients, also known as standardized regression coefficients, provide estimates of the relationships between the constructs in the structural model. These coefficients indicate the strength, direction, and statistical significance of the relationships. Presented as standardized values ranging from −1 to +1, higher absolute values represent stronger (predictive) relationships between constructs, while values closer to zero indicate weaker relationships. The significance of the path coefficients is assessed using the bootstrapping procedure, which answers the question: Are the relationships significantly different from zero? Bootstrapping is a nonparametric resampling technique that involves creating multiple bootstrap samples by randomly sampling with replacement from the original sample (Hair et al., 2011). It is recommended to generate a minimum of 5000 resamples. Through this process, standard errors, t-statistics, p-values, and confidence intervals of the parameters are obtained, facilitating the evaluation of proposed hypotheses.

As shown in Table 4, the People culture demonstrates a positive and statistically significant effect on the endogenous construct, Digital Culture. On the other hand, the Innovation, Goals, and Norms cultures exhibit a negative impact on Digital Culture. However, only the relationships between Goals culture → Digital culture and Norms culture → Digital culture appear to be statistically significant. Hence, this study provides empirical support only for hypotheses 1, 3, and 4.

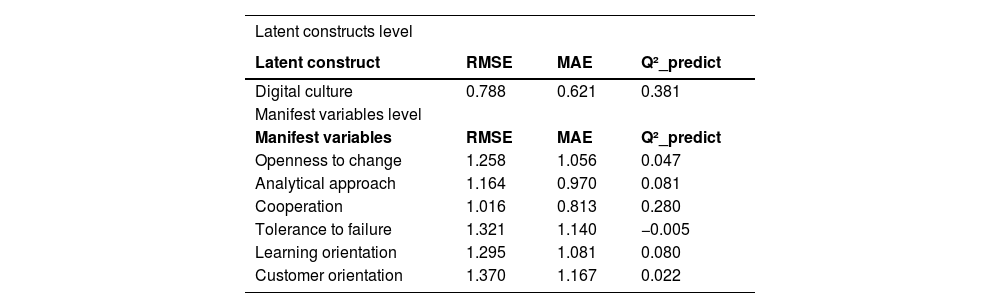

Predictive powerAs previously mentioned, this research is primarily focused on prediction. According to Shmueli and Koppius (2011), the predictive performance of a model refers to its ability to generate accurate predictions for new interpretable observations, whether they are temporal or cross-sectional. Therefore, this paper assesses the predictive ability of our model through cross-validation with retained samples (Evermann & Tate, 2016), with a specific emphasis on the key dependent construct, Digital Culture. To conduct this evaluation, we employed the PLS-predict algorithm (Shmueli et al., 2016), which is available in SmartPLS software version 3.2.9 (Ringle et al., 2015).

To analyze the results, our attention should be directed towards the Q2 value. Positive Q2 values indicate that the prediction error of the PLS-SEM results is lower than the prediction error obtained by simply using mean values. Consequently, the model demonstrates adequate predictive ability. In our case, the model satisfies this criterion for the Digital Culture construct and all of its indicators, except for Tolerance to failure (Table 5).

Predictive power of the model.

| Latent constructs level | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Latent construct | RMSE | MAE | Q²_predict |

| Digital culture | 0.788 | 0.621 | 0.381 |

| Manifest variables level | |||

| Manifest variables | RMSE | MAE | Q²_predict |

| Openness to change | 1.258 | 1.056 | 0.047 |

| Analytical approach | 1.164 | 0.970 | 0.081 |

| Cooperation | 1.016 | 0.813 | 0.280 |

| Tolerance to failure | 1.321 | 1.140 | −0.005 |

| Learning orientation | 1.295 | 1.081 | 0.080 |

| Customer orientation | 1.370 | 1.167 | 0.022 |

Note: MAE: Mean Absolute Error; RMSE: Root mean squared error; Q2: Goodness of prediction.

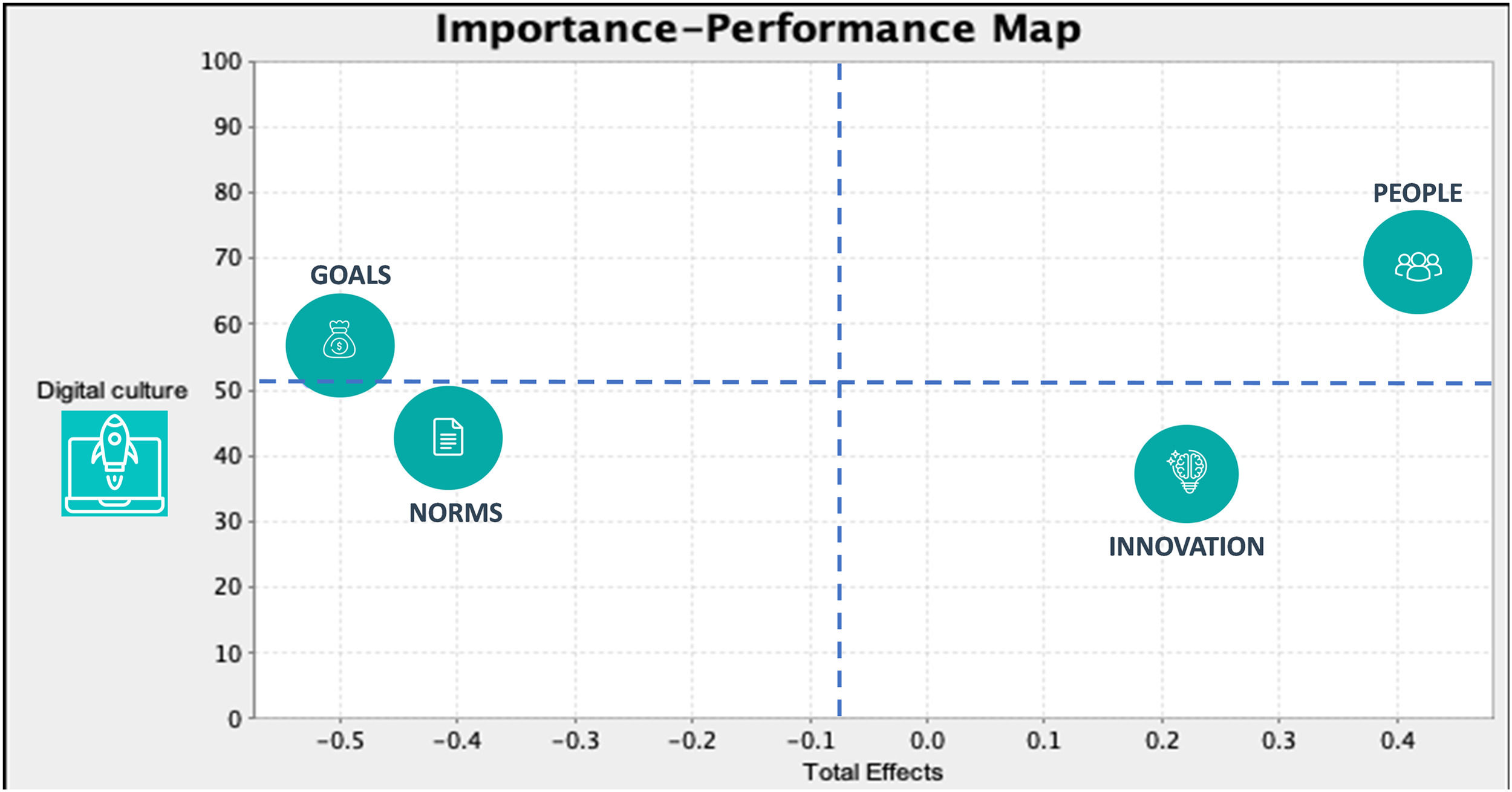

The PLS results presented earlier are further complemented by the application of the "Importance-Performance Map Analysis" (IPMA) technique, also known as Priority Map Analysis (Ringle & Sarstedt, 2016). In essence, the IPMA technique compares the total effects, which signify the relevance of antecedent constructs in determining a specific construct (referred to as the target construct), with the mean values of latent variable scores, which indicate their performance (Ringle & Sarstedt, 2016). The objective is to identify the antecedents that hold relatively greater importance in influencing the target construct. This information becomes crucial for decision-makers as it highlights the major areas that require focus or improvement.

Therefore, the relative levels of importance/performance of different constructs for the target construct indicate their logical order of deployment. Managers can initiate the process by increasing the deployment levels of constructs located in the lower right quadrant. Constructs/indicators found in the upper right quadrant are also significant and exhibit higher performance/deployment levels. Monitoring them would be sufficient to maintain or enhance their performance. On the other hand, constructs/indicators in the upper left quadrant are of lesser importance but demonstrate performance/deployment levels above the mean. This situation may suggest inadequate resource allocation.

As illustrated in Fig. 5, the People culture emerges as the most crucial factor in determining the target construct of the assessment, namely Digital culture. In terms of importance and level of deployment, the People culture surpasses the average and occupies the upper right quadrant. Following closely in importance is the Innovation culture, while the Norms and Goals cultures are relatively less influential, albeit still significant. Notably, the Innovation culture finds itself in the lower-right quadrant, indicating a noteworthy managerial implication. Despite its above-average importance, this culture lags in terms of deployment. Consequently, organizations should prioritize the promotion of disruptive values within their organizational culture to foster the growth of digital culture.

Discussion and conclusionsDiscussion of the main findingsThe main goal of this study has been to provide insights into the characteristics of a digital culture within organizations. This is evident through the prevalence of values such as customer adaptation, analytical approach, cooperation, tolerance to failure, learning orientation, and openness to change. These values promote the formation of cross-functional teams and encourage learning to generate optimized and agile responses. Moreover, it has been confirmed that the development of human capital is a genuine priority in companies with a strong digital culture.

Furthermore, we have validated the explanatory power of the classical approach consisting of the four cultural archetypes: People Culture, Innovation Culture, Goals Culture, and Norms Culture, originally proposed by Cameron and Quinn (1999) and based on the Competing Values Framework (Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1981). This framework aids in understanding the formation of the new archetype, Digital culture. The findings are reinforced by the high level of the R2 coefficient and the positive Q2 values, indicating that the prediction error of the PLS-SEM results is lower compared to using mean values alone. Consequently, the model exhibits adequate predictive capability.

At the hypothesis level (Table 6), it is particularly noteworthy that both Goals culture and Norms culture have a significant, yet negative, impact on the emergence of Digital culture. This implies that certain values associated with Goals culture (Results orientation, Excellence, Competitiveness, Pragmatism, Ambition, Leadership) and Norms culture (Formality, Coordination, Stability, Responsibility, Perseverance, Efficiency) are in competition with those of Digital culture, impeding its proper development and hindering the digital transformation process.

In line with this, the IPMA analysis (Fig. 5) reveals that People culture and Innovation culture play the most crucial role in shaping digital culture. However, only People culture surpasses the average in terms of performance. Hence, companies aiming to effectively implement digitalization should emphasize values such as Closeness, Commitment, Generosity, Loyalty, Teamwork, and Trust, which are characteristic of People culture. Simultaneously, they should not overlook values like Autonomy, Creativity, Daring, Dynamism, Innovation, and Risk tolerance, which are representative of Innovation culture. Therefore, at the organizational level, companies dominated by Goals culture or Norms culture that aspire to undergo a digital transformation should recognize the potential challenges they may face. Consequently, they should prioritize learning, team development, and cultivate a culture that supports this profound process of change (Kane, 2019; Nicolás-Agustín et al., 2021).

Theoretical implicationsThis paper contributes significantly to the literature on organizational culture and digital transformation. Firstly, it enhances our understanding and analysis of the values associated with digital culture, thereby expanding the conventional perception of organizational culture to include the digital mindset alongside traditional cultural archetypes. Recognizing the digital component of culture is crucial for businesses that heavily rely on digital technology for their operations and stakeholder relations. To this end, the Cultural Fit Assessment Method (CFAM) (Leal-Rodríguez et al., 2023) presents a methodological approach that is both innovative and robust, as it builds upon elements of the Competing Values Framework (Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1981) -a widely accepted and validated framework in the management of corporate culture. Hence, a significant contribution of this study is the adaptation and extension of the OCAI scale (Cameron & Quinn, 1999) to measure digital culture based on its fundamental underlying values.

Secondly, we contribute to the framework of functionalist theory by integrating it with structuralism, thereby providing a more comprehensive explanation of social processes. Functionalism focuses on how social units fulfill specific roles and contribute to the stability and maintenance of society. On the other hand, structuralism emphasizes the underlying patterns and linkages within social structures. A functionalist approach to assessing a social institution, such as an organization, would examine how it meets the needs of various stakeholders. In contrast, a structuralist approach would analyze the organizational relationships, power dynamics, and cultural significance associated with these interactions. By merging these perspectives, we can achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the organization as a social institution and how its functions are influenced by the underlying patterns and connections within it. Consequently, the combination of functionalism and structuralism enables a more nuanced and thorough comprehension of cultural change (Dyer, 1985; Wilkins & Dyer, 1988) by providing a theoretical framework that aids in better understanding the internal dynamics of cultural change, specifically the role of dominant cultural archetypes in shaping, developing, and transitioning to other archetypes, as observed in the case of digital culture.

Thirdly, we advance a research agenda that focuses on measuring culture based on archetypes (Richter et al., 2016; Grover et al., 2022) rather than the traditional approach based on discrete variables or values. This endeavor aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of digital culture. Archetypes represent universal patterns of behavior and experience that embody the collective unconscious of a culture. By measuring culture based on archetypes, researchers can gain profound insights into the underlying cultural patterns that shape an organization. In contrast, classical approaches that rely on discrete variables only provide a superficial understanding of cultural differences. In the context of the emergence of digital culture, we have a unique opportunity to develop a new cultural archetype that reflects the shared patterns of values among individuals in the digital age. This new archetype would offer a more comprehensive understanding of how digital technologies influence cultural norms, beliefs, and the ways in which people engage with the world. By incorporating digital culture into a research agenda based on archetypes, we can enhance our ability to compare and contrast different cultures, encompassing both traditional and digital realms. This approach yields valuable insights into how cultural values are expressed and perpetuated across diverse contexts, as well as how these values are shaped by technological advancements.

In summary, this paper makes a valuable contribution to the field of research on digital culture by defining the organizational values necessary for its implementation. It sheds light on the question of what type of organizational culture is required to embrace digitalization. This study represents a crucial initial step towards comprehending the impact of culture on successful digitalization. By identifying the cultural values that are crucial for digital transformation, we establish an ideal target digital culture. Consequently, we lay the foundation for future research on the role of organizational culture in digital transition. Moreover, this paper has broader implications for organizational culture research in general.

Managerial implicationsThe first managerial implication of this study relates to fostering a digital culture within firms. Specifically, HR departments should establish systems to identify their corporate values and utilize them as catalysts for digital change. It is crucial to recognize and strengthen poorly established digital culture values through cultural transformation techniques that facilitate an efficient digitalization process. Therefore, conducting an effective organizational culture diagnosis based on archetypes becomes a vital procedure in supporting the adoption of new technologies. To ensure the success of digitization, it is essential to perform an initial cultural diagnosis and engage in ongoing monitoring, as corporate culture is dynamic. More specifically, we provide practitioners with a target culture upon which they are advised to build their cultural change activities by identifying values that are essential for achieving or reinforcing a digital culture. The Cultural Fit Assessment Method (CFAM), based on the competing values framework (Quinn & Rohrbaurgh, 1983), can be employed by practitioners as a tool for managing culture during the digital transformation process. This tool enables practitioners to examine their current culture and identify areas that require cultural change as part of the digital transformation process.

A second managerial implication that arises from our results concerns the importance of fostering an enthusiastic, positive, and open mindset toward upcoming technological challenges and digital disruption. It is crucial for organizations to address their members' resistance to digitalization by adopting transparent practices aimed at motivating and engaging employees while reducing knowledge gaps regarding the transformation process. Although most transformation processes are primarily top-down, the willingness and commitment of employees to understand and embrace digitalization significantly impact its performance. Therefore, organizations must learn how to motivate both themselves and their staff. Employees need to recognize that their company's survival hinges on undergoing digitalization. Consequently, they should commit to enhancing their skills and supporting less digitally competent colleagues whenever possible. In this regard, investing in intergenerational mutual mentoring could be beneficial, where senior members are paired with younger ones to learn about the digital shift from them. The goal is to bridge the generational gap in the digital environment by facilitating the exchange of values, ideas, expectations, and abilities between older and younger individuals.

Thirdly, managers need to recognize the following points: (1) the formation of a digital culture archetype within organizations is a complex phenomenon that comprises multiple dimensions or sets of interacting values; (2) the detection and measurement of cultural archetypes provide a qualitatively superior methodology for cultural analysis compared to the use of measurement scales based on individual cultural dimensions, such as values; (3) within the same organization, multiple cultural archetypes may coexist simultaneously or to varying degrees of intensity; and (4) while a dominant archetype may exist in an organization due to strategic orientation, isomorphic pressures from other organizations, or external and internal environmental influences, cultures also evolve through conflicts and interactions between different cultural archetypes. These interactions can have both positive and synergistic effects or negative effects, acting as barriers to the development of other archetypes, as seen in the case of digital culture. Today's organizations are characterized by cultural complexity, where multiple archetypes and cultural values coexist and complement each other, but can also contradict each other. For instance, many organizations emphasize gender equality, yet discrimination against women at certain levels of their structure remains prevalent. This cultural complexity, with potential conflicts between archetypes, values, and microcultures, must be measured and analyzed when implementing any cultural intervention program.

The final implication of this study entails recognizing that merely harnessing new technologies and realizing the advantages of big data, as well as understanding how to utilize AI in data analysis, is inadequate. Consequently, the diagnosis and transformation of corporate culture should be perceived and fostered as an essential prerequisite to effectively navigate the digital revolution. By embracing both functionalist and structuralist paradigms, organizations acknowledge that cultural complexity, with its network of dynamic interactions and diverse social manifestations, is indispensable for organizational functioning. The abundance and diversity of cultural archetypes serve as valuable assets for organizations to navigate novel situations and challenges, including digitalization.

Limitations and future researchHowever, this work is subject to several limitations. Firstly, the sample size remains modest, focusing exclusively on businesses within a specific geographic area (Spain). Therefore, future endeavors aim to expand the scope of the study to include other countries and economic sectors, enhancing the robustness and generalizability of the findings and implications. Secondly, the study solely relies on one method to gather the perceptions of the surveyed individuals. Exploring alternative methodologies, such as fsQCA, could unveil additional insights that contribute to a deeper understanding of the interactions between digitalization and performance (Ribeiro-Navarrete et al., 2021). Future research endeavors also aim to assess the impact of different cultural archetypes, including the proposed new digital culture archetype, on various financial and organizational performance metrics. This aligns with the trajectory of recent empirical studies on this topic, such as those conducted by Khan et al. (2022) and Naveed et al. (2022).

The authors would like to thank the SEJ-573 Research Group for its support in the development of this work. The authors acknowledge a financial interest in the Cultural Fit Assessment Method (CFAM).