Concern about environmental problems has led to more attention being paid to the sustainable development objective. Social entrepreneurship, and entrepreneurship in general, show a direct relationship with this objective, due mainly to the activities carried out by entrepreneurs regarding the development of new products, the search for new markets, and the introduction of innovations. Because of this, it is important to identify the variables that influence both types of entrepreneurship to adequately design measures to stimulate sustainable development through these activities. These variables can be grouped into two groups: sociocultural factors and economic factors. The objective of this paper is to analyze the behavior of these two groups over general entrepreneurship and social entrepreneurship, in addition to the impact of these two types of entrepreneurship on sustainable development. To carry out this analysis, we have developed an empirical analysis with structural equations for the case of 15 OECD countries between 2015 and 2016.

La preocupación por los problemas ambientales ha llevado a que se preste más atención al objetivo de desarrollo sostenible. El emprendimiento social, y el emprendimiento en general, muestran una relación directa con este objetivo, debido principalmente a las actividades llevadas a cabo por los emprendedores en relación con el desarrollo de nuevos productos, la búsqueda de nuevos mercados y la introducción de innovaciones. Debido a esto, es importante identificar las variables que influyen en ambos tipos de emprendimiento para diseñar adecuadamente medidas para estimular el desarrollo sostenible a través de estas actividades. Estas variables se pueden agrupar en dos grupos: factores socioculturales y factores económicos. El objetivo de este trabajo es analizar el comportamiento de estos dos grupos sobre el emprendimiento general y el emprendimiento social, además del impacto de estos dos tipos de emprendimiento en el desarrollo sostenible. Para llevar a cabo este análisis, hemos desarrollado un análisis empírico con ecuaciones estructurales para el caso de 15 países de la OCDE entre 2015 y 2016.

In recent decades, the study of entrepreneurship has been studied from different perspectives. One approach is to analyze the potential effects of entrepreneurship on economic growth, in respect of the benefits that greater economic growth has on employment and the well-being of society, especially in times of crisis. This has been the focus of a considerable body of research (e.g., Audretsch & Keilbach, 2004a, 2004b; Audretsch, 2005; Alpkan, Bulut, Gunday, Ulusoy, & Kilic, 2010; Acs, Audretsch, Braunerhjelm, & Carlsson, 2012; Méndez-Picazo, Galindo-Martín, & Ribeiro-Soriano, 2012; Nissan, Galindo, & Méndez, 2012; Castaño, Méndez, & Galindo, 2016; Doran, McCarthy, & O’Connor, 2018; Aeeni, Motavaseli, Sakhdari, & Dehkordi, 2019; Stoica, Roman, & Rusu, 2020). These analyses conclude that there is a direct relationship entrepreneurship and economic growth. Therefore, the policy maker can add the factor of entrepreneurship to the traditional ones, such as public spending and taxes, for stimulating growth.

For this reason, interest has arisen as to what factors would, in turn, influence entrepreneurship to determine the most appropriate actions to stimulate these factors and, thus, stimulate economic growth. Various factors have been considered, with special attention on innovations (e.g., Galindo & Méndez, 2013, 2014; Ferreira, Fernandes, & Ratten, 2017; Mazzarol & Reboud, 2017; Schmitz, Urbano, Dandolini, de Souza, & Guerrero, 2017; Betts, Laud, & Kretinin, 2018; Malerba & McKelvey, 2019; Medeiros, Marques, Galvão, & Braga, 2020), institutions (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2008; Acemoglu, 2003; Acs, Estrin, Mickiewicz, & Szerb, 2018; Bosma, Content, Sanders, & Stam, 2018; Boudreaux, Nikolaev, & Klein, 2019; Elert & Henrekson, 2017; Galindo-Martín, Méndez-Picazo, & Castaño-Martínez, 2019; Urbano, Turro, & Aparicio, 2019), human capital (Autio & Acs, 2010; Capelleras, Contin-Pilart, Larraza-Kintana, & Martin-Sanchez, 2019; Nasiri & Hamelin, 2018) and other aspects, even considering the feedback effects in the analysis. Among others, these elements could indicate how the economic growth could have a positive effect on entrepreneurship (Galindo & Méndez, 2014).

These analyses conclude that there is a direct relationship between entrepreneurship and economic growth. Therefore, the political decision-maker has an additional factor to the traditional ones, public spending, taxes, etc., to stimulate growth. That is why the interest has arisen to know what factors would influence entrepreneurship in turn, to specify what would be the most appropriate actions to stimulate this factor and thus stimulate it through economic growth.

The worrisome environmental situation of many countries has aroused growing interest in establishing actions to combat current problems without compromising the situation of future generations. This has caused rethinking of the objective to be achieved, which has led to increasing attention being paid to sustainable development, and the emergence of new activities that foster the appearance of new economic agents in economic activity; in our case, social entrepreneurship.

Thus, sustainable development has become the essential objective of political decision-makers. And, from this new perspective, it is important to know, as happened in the case of economic growth, the factors that influence said development. In this sense, contributions arise that consider social entrepreneurship as a new factor to consider in changing the objective of economic growth for sustainable development (Johnson & Schaltegger, 2019; Schaltegger, Hörisch, & Loorbach, 2020) to avoid compromising the situation of future generations through current policies designed to achieve present-day well-being.

Therefore, taking the previous comments into account, one of the first questions to consider is the relationship between both general and social entrepreneurship and sustainable development.

But it is also interesting to ascertain the factors that can stimulate both types of entrepreneurship, as this would help in designing appropriate measures to promote sustainable development through business activity. In this case, unlike the analyses that have been carried out, the main factors are going to be grouped into two main categories: sociocultural and economic. This choice is essentially due to the fact that both the social and cultural and the economic environment influence entrepreneurial activity. Therefore, it is important to determine the relationship of these factors with each of the types of entrepreneurship considered and show the relevance in each of the cases.

Therefore, the objective of this paper is to conduct a double empirical analysis. Firstly, to analyze the relationship between both general entrepreneurship and social entrepreneurship and sustainable development and, secondly, to study the relationship of sociocultural and economic factors with both types of entrepreneurship. The empirical analysis proposes a structural equation modeling with partial least squares, allowing the introduction of latent variables and the estimation of multiple relationships, thus improving upon multivariate techniques that can only examine one relationship at a time (Barclay, Higgins, & Thompson, 1995; Chin, Marcolin, & Newsted, 2003).

Section 2 explains the main theoretical aspects related to these relationships. In section 3 the empirical analysis for the case of 15 OECD countries is developed for the period between 2015–2016. Section 4 provides the conclusions.

Theoretical analysisEntrepreneurship and social entrepreneurshipEntrepreneurship has had positive effects on economic growth, and this relationship has been analyzed thoroughly in recent decades (e.g., Audretsch & Keilbach, 2004a, 2004b; Audretsch, 2005; Alpkan et al., 2010; Acs et al., 2012; Méndez-Picazo et al., 2012; Nissan et al., 2012; Castaño et al., 2016; Doran et al., 2018; Stoica et al., 2020). This positive relationship is due mainly to the activities of entrepreneurs regarding, for example, the development of new products, the search for new markets, and the introduction of innovations, which have positive effects on economic growth, which, in turn, has positive effects on job creation and social well-being. Given this possibility of stimulating economic growth through entrepreneurial activity, the specialized literature has also focused on determining the factors that can stimulate entrepreneurship to design appropriate economic policy.

Furthermore, the increasing interest in environmental problems suffered by economies has led to attention being paid to other variables and objectives that take these problems into account. For this reason, the objective of economic growth gives way to the objective of “sustainable development,” which refers to the attempt to achieve economic development that will satisfy current needs without compromising the situation of future generations (UN, 1987). This implies, among other issues, the alteration of traditional business practices that are considered environmentally unsustainable, replacing them with others that are environmentally sustainable, thus reducing environmental damage. Therefore, the term sustainable development implies the use of non-renewable resources in such a way as to make them viable and usable by future generations.

As in the case of economic growth, entrepreneurial activity could develop activities that respect the environment and, therefore, it could also be a stimulating factor for sustainable development.

Consideration of environmental problems has led to the emergence of other activities of and other ways of operating by economic agents. The concept of social entrepreneurship has arisen and has been considered gradually in analyses (Middermann, Kratzer, & Perner, 2020). Though different definitions of social entrepreneurship have been offered (Dees, 1998; Hockerts, 2017; Light, 2006, 2009; Mair & Martí, 2006), from the perspective of this paper, we can consider it in general terms as a process involving opportunities and actions that try to solve social and environmental problems by searching for innovative solutions (Brooks, 2009; Méndez-Picazo, Ribeiro-Soriano, & Galindo-Martín, 2015; Miller, Grimes, McMullen, & Vogus, 2012; Miska, Stahl, & Mendenhall, 2013; Nga & Shamuganathan, 2010).

As in the case of general entrepreneurship, social entrepreneurship has a positive effect on sustainable development through its related activities, facilitating job creation, and, thus, increasing the aggregate demand of the economy that will stimulate economic growth.

In enhancing sustainable development, both general (Doran & Ryan, 2016; Liao, 2018) and social entrepreneurship play an important role (Johnson & Schaltegger, 2019). Both are interested in achieving the objective of sustainable development, as environmental responsibility represents a good business opportunity and will allow entrepreneurs access new markets, improve their image with stakeholders, and differentiate their products (Ambec & Lanoie, 2008). In short, general and social entrepreneurship have a positive relationship with sustainable development. For this reason, it is interesting to determine the factors that influence both types of entrepreneurship. In this sense, different factors, such as institutions (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2008; Acemoglu, 2003; Acs et al., 2018; Bosma et al., 2018; Boudreaux et al., 2019; De Beule, Klein, & Verwaal, 2019; Diab & Metwally, 2019; Urbano, Aparicio, & Audretsch, 2019; Elert & Henrekson, 2017; Galindo-Martín et al., 2019), education, and social climate have been considered. From the perspective of this paper the different factors are grouped in two categories: sociocultural and economic.

Sociocultural factorsRegarding sociocultural factors, it must be considered that the social environment is of great importance in stimulating entrepreneurial activity, basically from two perspectives. From the institutional perspective, without efficient institutions that try to protect property rights, few economic agents would be interested in developing an entrepreneurial activity. The institutions are in charge of establishing the rules of the game by which this activity will be carried out. If these rules are either not clear or involve a delay in decision-making, due to excessive bureaucracy, for example, entrepreneurial activity will be affected negatively. For this reason, some studies indicate that the structure of institutions influences the type of entrepreneurship existing in society (Baumol, 1990; Boettke & Coyne, 2003; Gregori, Wdowiak, Schwarz, & Holzmann, 2019; Sobel, 2008), whereas other papers indicate that such structure may discourage entrepreneurial activity (Baumol, 1990; Johnson, Kaufmann, & Shleifer, 1997; Hall & Sobel, 2008). The structure of institutions can be divided into two large groups: formal and informal. Formal institutions are characterized by having a very strong cultural component (North, 1990), which is what encourages entrepreneurs to carry out their activities. For this reason, the rules designed by this type of institution are aimed at increasing economic freedom (Powell & Rodet, 2012), and reducing corruption would have a positive effect on entrepreneurship (Anokhin & Schulze, 2009; Avnimelech, Zelekha, & Sharabi, 2014; Berdiev & Saunoris, 2018; Cherrier, Goswami, & Ray, 2018; Zhang, 2019).

In this group, the role of education and skills’ improvement must also be considered (Gavron, Cowling, Holtham, & Westall, 1998; Reynolds, Hay, & Camp, 2000), as a higher educational level makes it easier for individuals to favor the introduction of and desire for innovations and to make more efficient use of the different instruments and tools necessary to carry out their activity by allowing entrepreneurs to identify the market opportunities that may arise (Barreneche García, 2013; Portuguez Castro, Ross Scheede, & Gómez Zermeño, 2019; Rashid, 2019). In this case, the variable to consider would be schooling, as a proxy variable for education and human capital.

Economic factorsThe second group of factors to consider are economic. In this area, there are different variables that could stimulate entrepreneurial activity, both general and social. The first factor is the fiscal policy designed by the government. In general, government activity can stimulate entrepreneurship (Audretsch & Link, 2019; Audretsch, 2003) by correcting failures that can occur in markets due to either external shocks or misallocation of resources. Therefore, the government can stimulate entrepreneurial activity through its spending policies (McMullen, Bagby, & Palich, 2008; Gnyawali & Fogel, 1994), for example, by improving income distribution and investing in education and R&D. These two possibilities are considered in the model estimated in the following section. Investment in education has been included as a sociocultural factor, since, as indicated, what is intended is that entrepreneurs use the different instruments more efficiently to conduct their activities and can better identify the opportunities offered by markets.

Regarding income distribution, its importance lies in the fact that an adequate social climate is generated that facilitates economic activity, which supposes an additional incentive to stimulate entrepreneurship, both general and social (Galindo Martin, Méndez Picazo, & Alfaro Navarro, 2010; Castaño et al., 2016). Government measures can also stimulate entrepreneurship indirectly through employment policy. A reduction in unemployment is a stimulus to demand in the market and, therefore, a greater quantity of already produced are demanded and new products can be offered. This provides the possibility of increasing production of activities in development and also provides new possibilities and market niches that would stimulate the appearance of new entrepreneurs. For this reason, a positive relationship between employment and general and social entrepreneurship is expected.

However, there are also detractors of government policies, considering that public measures can allow non-productive entrepreneurs to continue operating in the market, which would negatively affect economic growth (Campbell & Mitchell, 2012).

The other two economic factors to consider are investment spending and research and development (R&D). As already indicated, both variables allow entrepreneurs to be more competitive and, especially, to be able to create and implement technology that is less harmful to the environment, even prompting other entrepreneurs to include these advances in their own production processes (Amorós, Poblete, & Mandakovic, 2019, Urbano et al., 2019b, Duguet, 2004; Yun, Kwon, & Choi, 2019).

Considering all these theoretical aspects, the model to be estimated in the following section includes two groups of sociocultural and economic factors. Both factors have a positive relationship with general entrepreneurship and social entrepreneurship. The sociocultural variables considered are corruption, economic freedom, schooling, and human capital. The variables considered as economic factors are income distribution, employment, spending on fixed capital, and spending on R&D. Finally, both types of entrepreneurship have a positive relationship with sustainable development.

Empirical analysisData and methodsA quantitative, correlational, and explanatory empirical analysis is carried out to identify causal relationships among variables by using a structural equation model (SEM). To calculate the proposed model, a multiple regression with Partial Least Squares (PLS) is used. This technique allows one to build research models by establishing latent variables. Latent variables are variables that are not observed directly but are inferred from other observed variables (indicators) (Haenlein & Kaplan, 2004).

PLS is model validation mainly oriented to causal-predictive analysis and is usually used in situations of high complexity, but low theoretical information (Roldán & Sánchez-Franco, 2012). It is also recommended for use with variables with non-normal distributions, non-experimental research with data obtained from surveys, a not very large study sample, and a theory that has not yet been developed in a solid way (Aldás-Manzano, 2012; Rigdon, Sarstedt, & Ringle, 2017; Sarstedt, Bengart, Shaltoni, & Lehmann, 2018; Hair, Risher, Sarstedt, & Ringle, 2019).

To contrast the previous theoretical relationship, data from 15 OECD countries (Belgium, Finland, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States) from between 2015–2016 have been used, providing a sample of 30 records, although a small sample is suitable for a PLS estimate (Hair, Hult, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2016). The SEM model has been estimated using the PLS technique with SmartPLS software 3. (Ringle, Wende, & Becker, 2015).

The SEM has two elements (Henseler, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2015; Henseler, Ringle, & Sinkovics, 2009): (a) the structural model or inner model that represents constructs (circles) or latent variables and the relationship between exogenous and endogenous variables, and (b) measurement models or outer models that show constructs and the indicator variables (rectangles) (2016, Hair, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2011).

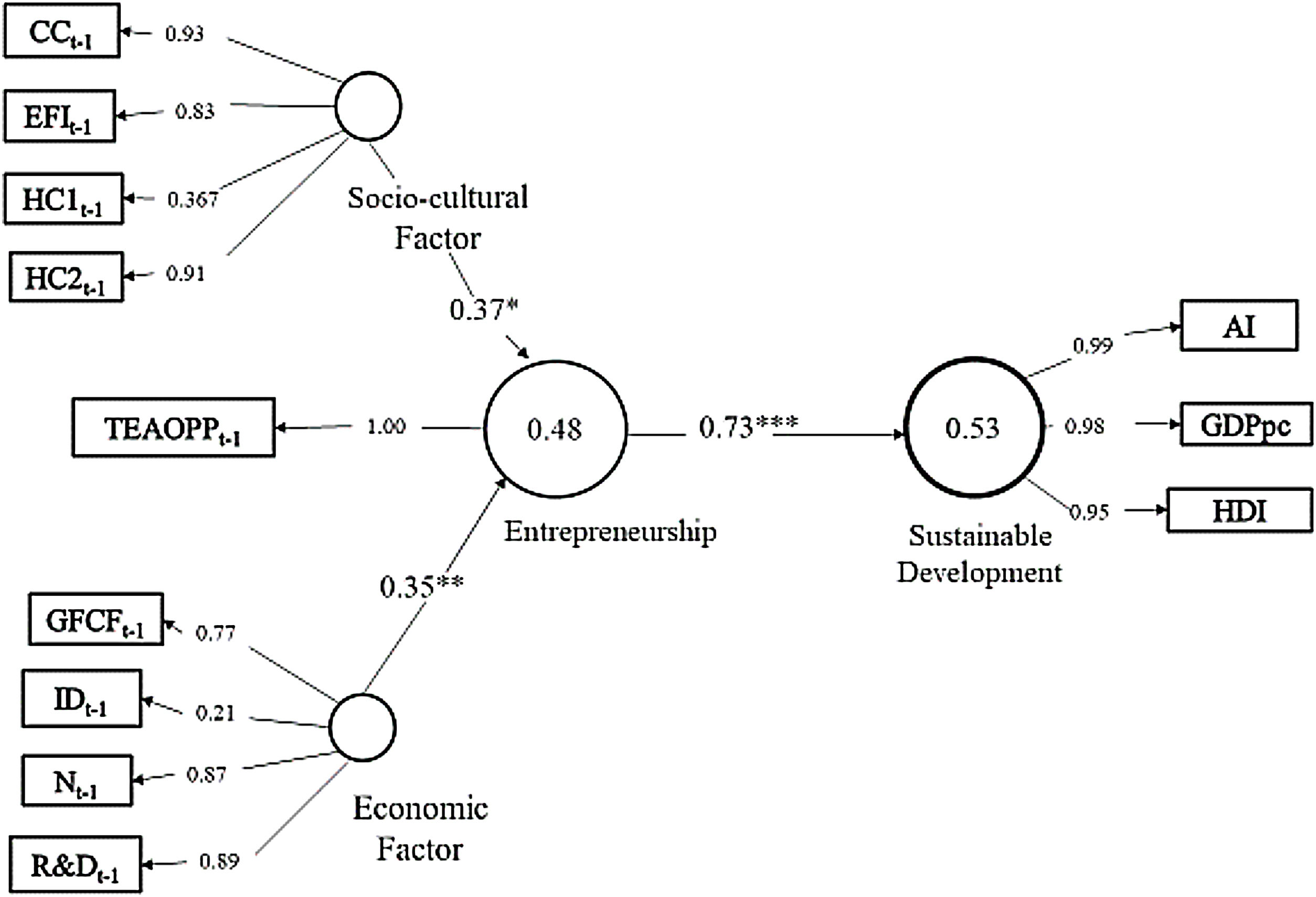

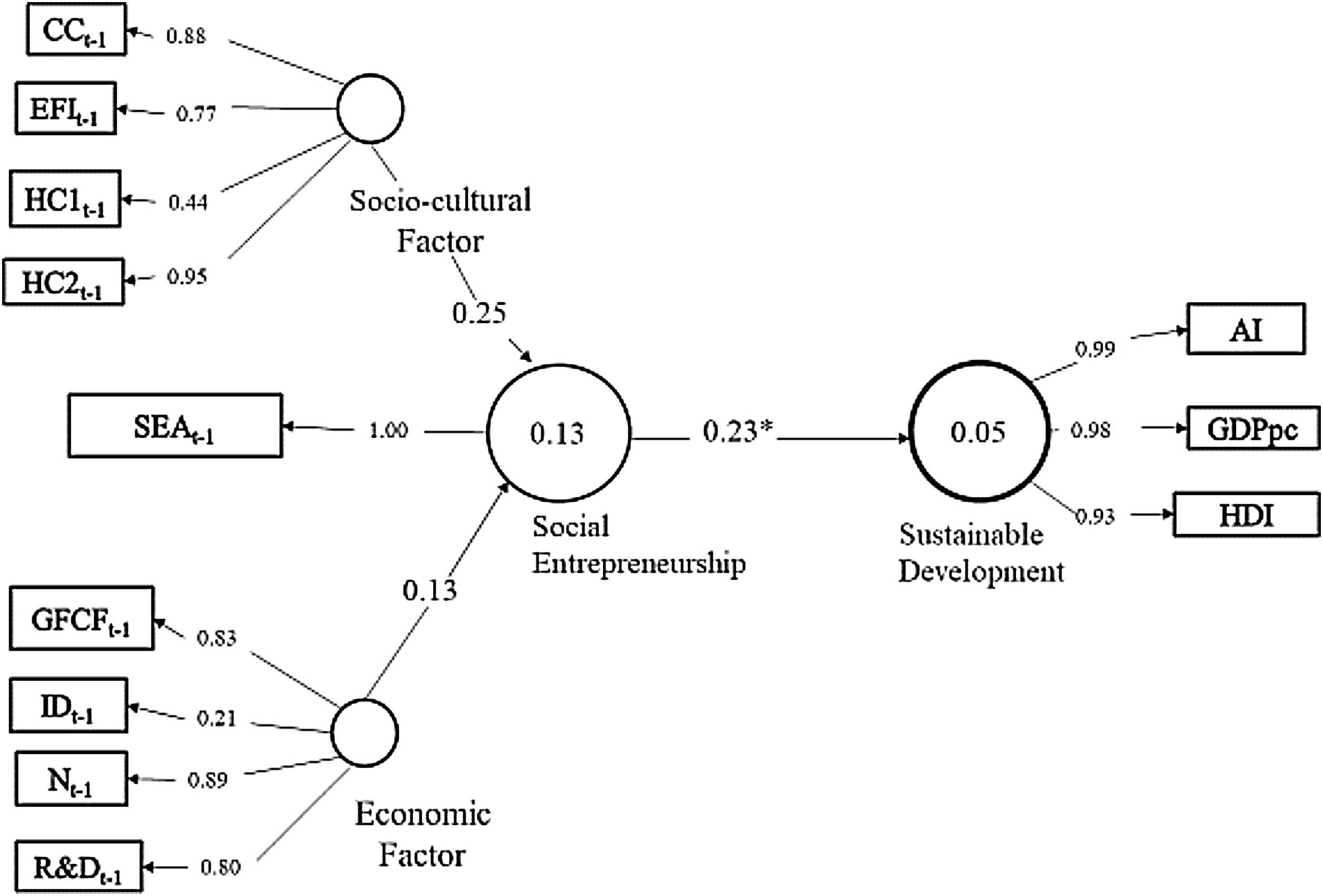

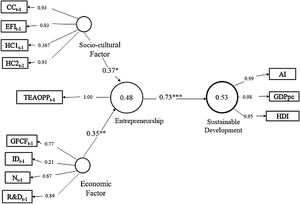

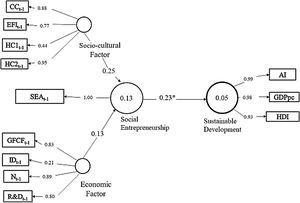

The two proposed models are reflective (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). A reflective model is common in social sciences, and it is directly based on classical test theory. According to Nunnally and Bernstein (1994), the measurement model represents the effects (or manifestations) of an underlying construct (Diamantopoulos, Riefler, & Roth, 2008).

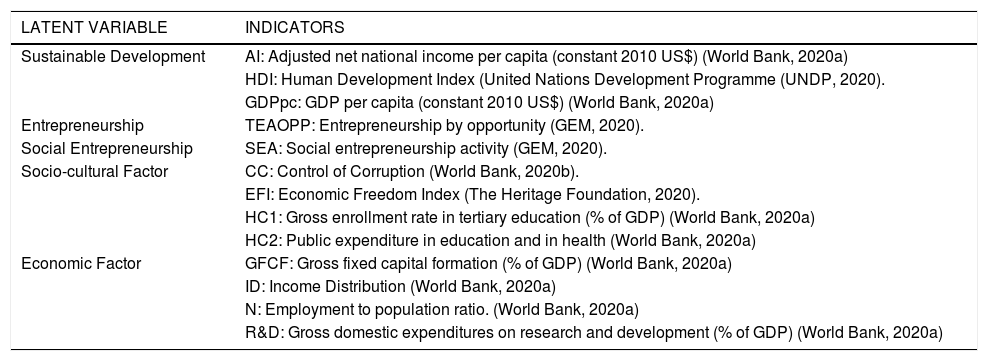

Table 1 shows the indicators that have been assigned to each of the latent variables.

Definition of variables.

| LATENT VARIABLE | INDICATORS |

|---|---|

| Sustainable Development | AI: Adjusted net national income per capita (constant 2010 US$) (World Bank, 2020a) |

| HDI: Human Development Index (United Nations Development Programme (UNDP, 2020). | |

| GDPpc: GDP per capita (constant 2010 US$) (World Bank, 2020a) | |

| Entrepreneurship | TEAOPP: Entrepreneurship by opportunity (GEM, 2020). |

| Social Entrepreneurship | SEA: Social entrepreneurship activity (GEM, 2020). |

| Socio-cultural Factor | CC: Control of Corruption (World Bank, 2020b). |

| EFI: Economic Freedom Index (The Heritage Foundation, 2020). | |

| HC1: Gross enrollment rate in tertiary education (% of GDP) (World Bank, 2020a) | |

| HC2: Public expenditure in education and in health (World Bank, 2020a) | |

| Economic Factor | GFCF: Gross fixed capital formation (% of GDP) (World Bank, 2020a) |

| ID: Income Distribution (World Bank, 2020a) | |

| N: Employment to population ratio. (World Bank, 2020a) | |

| R&D: Gross domestic expenditures on research and development (% of GDP) (World Bank, 2020a) |

Three different indicators have been used to measure the latent variable “Sustainable Development.” AI shows the adjusted net national income calculated by gross national income minus consumption of fixed capital and natural resources’ depletion; The Human Development Index (HDI) is a statistical indicator of human development that is produced each year by the United Nations. It measures three dimensions: health, education, and having a decent standard of living. The HDI is the geometric mean of normalized indices for each of the three dimensions; the GDPpc variable is GDP per capita in constant 2010 U.S. dollars (World Bank, 2020a).

To measure “Entrepreneurship,” the indicator TEAOPP is the percentage of the population aged 18–64 years who are entrepreneurs and whose main motivation is to benefit from an opportunity. This kind of entrepreneur claims to be driven by opportunity, as opposed to finding no other option for work.

Conversely, “social entrepreneurial activity” (SEA).1 The GEM define SEA as any kind of activity, organization, or initiative that has a particularly social, environmental, or community objective. This might include providing either services or training to socially deprived or disabled persons, activities aimed at reducing either pollution or food-waste, and organizing self-help groups for community action (Bosma, Schott, Terjesen, & Kew, 2015).

Finally, the latent variable “Socio-cultural Factor” comprises four indicators: The Economic Freedom Index (EFI) from The Heritage Foundation, control of corruption (CC) from the World Bank (2020b), and two indicators to measure human capital (HC). According to Wennekers, Van Wennekers, Thurik, and Reynolds (2005)) greater control of corruption favors business activity in developed countries, opportunity entrepreneurship in particular, and, in addition, excessive bureaucratic procedures indicate the inadequate functioning of institution. This is one of the main obstacles to entrepreneurial activity, which is why we chose the EFI indicator, as better functioning markets, protection of property rights, and better regulation favor entrepreneurship (Jacob & Michaely, 2017; Chambers & Munemo, 2019). As already mentioned in theoretical analysis, human capital and knowledge also play a key role in innovation and allowing the entrepreneur to be more competitive and introduce innovations in the market that indirectly favor sustainable development (Malerba & McKelvey, 2019; Poschke, 2018).

The CC indicator includes the opinions of individuals on how public power performs its functions for private, considering all kinds of corruption, both petty and grand types, in addition to the “capture” of the state by elites and private interests. The indicator has values from 0–100, with the lowest rank being 0 and the highest being 100 (World Bank, 2020b).

The EFI indicator is a complex index that measures economic freedom based on 12 quantitative and qualitative factors, grouped into four broad economic freedom categories: rule of law (property rights, government integrity, judicial effectiveness), government size (government spending, tax burden, fiscal health); regulatory efficiency (business freedom, labor freedom, monetary freedom), and open markets (trade freedom, investment freedom, financial freedom). Each of the twelve economic freedoms within these categories is graded on a scale of 0–100 (The Heritage Foundation, 2020).

HC1 is gross enrollment rate in tertiary education with respect to total enrollment at all levels of education, and HC2 is the sum of gross public expenditures in education and in health, expressed as a percentage of GDP.

Finally, we present the latent variable “Economic Factor.” the indicators for this variable are: Gross fixed capital formation, expressed as a percent of GDP (GFCF); gross domestic expenditures on research and development, expressed as a percent of GDP (R&D); employment to population ratio, which is the proportion of a country's population that is employed (N); and the indicator Income Distribution (ID) which is calculated like hundred minis GINI index to achieve internal coherence of the construct; this indicator measures how the distribution of income among either individuals or households within an economy deviates from a perfectly equal distribution. Therefore, a high value of ID shows a better income distribution. These indicators come from the World Bank's World Development Indicators database (World Bank, 2020a).

ResultsFigs. 1 and 2 show the graphic representation of the considered model. To calculate this relationship, some constructs are delayed one year, due to entrepreneurship needing some time to influence sustainable development, and social factor and economic factor have to in the same period that entrepreneurship; to represent that the constructs are delayed, the subscript (t-1) is added to the constructs in Figs. 1 and 2. Therefore, the construct sustainable development uses data from 2016 to 2017, and the other constructs use data from 2015 to 2016.

This model follows the theoretical framework set out in the previous section. This diagram represents the relation among latent variables and the main results of the estimation. This graphical representation shows two statistical models: (a) the structural model or inner model, which represents constructs (circles) or latent variables and the relationship between exogenous and endogenous variables, and (b) the measurement models or outer models of the constructs and the indicator variables (rectangles) (2016, Hair et al., 2011).

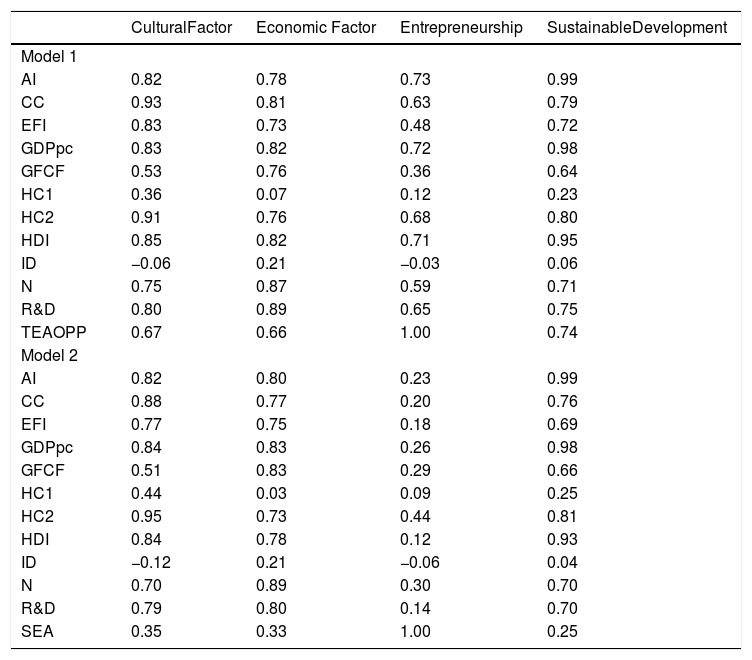

The study of cross loading appears in Table 2. As cross-loads are always greater for the latent variables on which the respective items are loaded, the indicators would be assigned correctly to each latent variable.

Cross-loads for convergent validity.

| CulturalFactor | Economic Factor | Entrepreneurship | SustainableDevelopment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | ||||

| AI | 0.82 | 0.78 | 0.73 | 0.99 |

| CC | 0.93 | 0.81 | 0.63 | 0.79 |

| EFI | 0.83 | 0.73 | 0.48 | 0.72 |

| GDPpc | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.72 | 0.98 |

| GFCF | 0.53 | 0.76 | 0.36 | 0.64 |

| HC1 | 0.36 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.23 |

| HC2 | 0.91 | 0.76 | 0.68 | 0.80 |

| HDI | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.71 | 0.95 |

| ID | −0.06 | 0.21 | −0.03 | 0.06 |

| N | 0.75 | 0.87 | 0.59 | 0.71 |

| R&D | 0.80 | 0.89 | 0.65 | 0.75 |

| TEAOPP | 0.67 | 0.66 | 1.00 | 0.74 |

| Model 2 | ||||

| AI | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.23 | 0.99 |

| CC | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.20 | 0.76 |

| EFI | 0.77 | 0.75 | 0.18 | 0.69 |

| GDPpc | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.26 | 0.98 |

| GFCF | 0.51 | 0.83 | 0.29 | 0.66 |

| HC1 | 0.44 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.25 |

| HC2 | 0.95 | 0.73 | 0.44 | 0.81 |

| HDI | 0.84 | 0.78 | 0.12 | 0.93 |

| ID | −0.12 | 0.21 | −0.06 | 0.04 |

| N | 0.70 | 0.89 | 0.30 | 0.70 |

| R&D | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.14 | 0.70 |

| SEA | 0.35 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 0.25 |

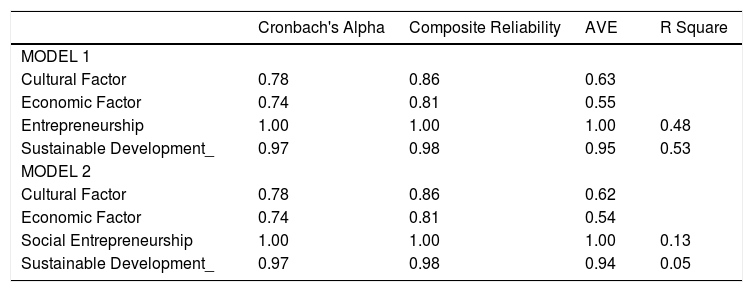

The reliability and validity of the measurement model are presented below. The internal consistency reliability is measured by using Jöreskog (1971) composite reliability. Higher values generally indicate higher levels of reliability (Diamantopoulos, Sarstedt, Fuchs, Wilczynski, & Kaiser, 2012). Another important measure of reliability is the relationship between each indicator and its construct, which is measured by the value of Cronbach's alpha. It is established that the construct has internal consistency when the value of Cronbach's alpha is greater than 0.7 (Barclay et al., 1995; Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). However, Cronbach’s alpha is a less precise measure of reliability than is composite reliability, as the items are unweighted. Conversely, with composite reliability, the items are weighted based on the construct indicators’ individual loadings and, hence, this reliability is higher than is that of Cronbach’s alpha (Hair et al., 2019). Thus, as can be observed in Table 3, all the latent variables have a Cronbach's Alpha higher than 0.7 and a Composite Reliability higher than 0.8.

Reliability and validity of the outer models.

| Cronbach's Alpha | Composite Reliability | AVE | R Square | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MODEL 1 | ||||

| Cultural Factor | 0.78 | 0.86 | 0.63 | |

| Economic Factor | 0.74 | 0.81 | 0.55 | |

| Entrepreneurship | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.48 |

| Sustainable Development_ | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 0.53 |

| MODEL 2 | ||||

| Cultural Factor | 0.78 | 0.86 | 0.62 | |

| Economic Factor | 0.74 | 0.81 | 0.54 | |

| Social Entrepreneurship | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.13 |

| Sustainable Development_ | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 0.05 |

In addition, Average Variance Extracted (AVE) indicates the variance extracted from the indicators, including the common variability absorbed by the latent variable. A value greater than 0.5 can be accepted as a good measure to fit (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Fornell, 1982). Also, it is observed that this criterion is fulfilled for all the latent variables of both models (see Table 3).

The R2 coefficient represents the combined effects of exogenous latent variables on the endogenous latent variable. Thus, the coefficient represents the amount of variance in the endogenous construct that is explained by all of the exogenous constructs linked to it. This coefficient is calculated as the squared correlation between the actual and the predictive value of a specific endogenous construct (Rigdon, 2012; Sarstedt et al., 2018). All the endogenous latent variables have values greater than 0.1 (Falk & Miller, 1992), except for sustainable development in model 2. However, the values for R2 in model 1 are estimated at approximately 0.5, which indicates a determining effect of the exogenous variables on the endogenous variable.

For evaluating the statistical significance of the latent regression coefficients, PLS used a bootstrapping technique. Such a technique analyses the significance of the relationships between variables. Fig. 1 shows that all relationships among variables are significant, (p-value * = p ≤ 10%; **= p ≤ 5%; ***= p ≤ 1%). In most settings, researchers choose a significance level of 5%, which implies that the p-values must be lower than 0.05 to render the relationship under consideration significant. However, in exploratory studies it is common to use a significance level of 10% (Hair et al., 2016).

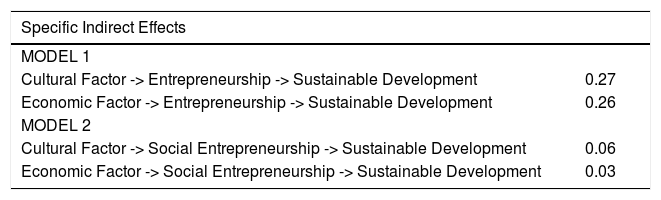

Table 4 shows the total indirect effects between latent variables. These indirect effects are added to the direct effects that appear in Fig. 1. These effects are positive and higher in model 1.

Indirect effects between latent variables.

| Specific Indirect Effects | |

|---|---|

| MODEL 1 | |

| Cultural Factor -> Entrepreneurship -> Sustainable Development | 0.27 |

| Economic Factor -> Entrepreneurship -> Sustainable Development | 0.26 |

| MODEL 2 | |

| Cultural Factor -> Social Entrepreneurship -> Sustainable Development | 0.06 |

| Economic Factor -> Social Entrepreneurship -> Sustainable Development | 0.03 |

The main results obtained by comparing the two models show that both types of entrepreneurship, general and social, have a positive effect on sustainable development, as shown by Ambec and Lanoie (2008) and Liao (2018), but the effect is greater in the case of general entrepreneurs (0.73 and significance of p ≤ 1%) than in the case of social entrepreneurs (0.23 and significance of p ≤ 10%).

On the one hand, sociocultural factors are observed to be positively related to general entrepreneurial activity, with a coefficient of 0.37 and significance of p ≤ 10%, whereas, in the case of social entrepreneurs, the coefficient is less than 0.25. If the outer loads are compared, CC and EFI are observed to have high outer loads in both models, but the outer loads are higher in the case of general entrepreneurs. Therefore, proper management of institutions would have a positive effect in both types of entrepreneurship, in line with the findings of Sobel (2008) and Powell and Rodet (2012). On the other hand, with respect to human capital, we verify that the indicator HC2 has a greater weight than does HC1 in both cases, and this is more prominent in the case of social entrepreneurs. Thus, public policies aimed at investing in human capital through public education and public health will stimulate both types of entrepreneurial activity.

Finally, economic factors are related positively to general entrepreneurial activity, showing a coefficient of 0.35 and significance of p ≤ 5%. The coefficient is lower in the case of social entrepreneurs (0.13). Regarding the analysis of the outer loads, employment ratio presents higher values in both cases; that is the greater the employment, the greater the stimulation of demand, which has a positive effect on entrepreneurial activity. On the other hand, income distribution is less important than are the other indicators. Finally, investment and R&D investment also have remarkable effects in both cases. Therefore, public spending policies that improve employment, income distribution, and investment in R&D would stimulate both types of entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurship is one of the variables that has been considered when analyzing the factors that improve economic growth. Increased awareness of environmental problems has changed the goal to be achieved, considering the effects on sustainable development. And the role of the social entrepreneur in this relationship has also been considered.

In short, the estimated models show that both factors, sociocultural and economic, have a greater impact on general entrepreneurship than on social entrepreneurship. On the one hand, sociocultural factors, corruption, and economic freedom have a greater effect on general entrepreneurship, whereas variables related to training and human capital have a greater impact on social entrepreneurship. Therefore, measures aimed at improving the development of institutions and designed to reduce corruption and provide a greater margin for action in the markets would have a greater impact on general entrepreneurship, whereas measures aimed at improving education and health would have a higher effect on social entrepreneurship.

In the case of economic factors, spending on gross fixed capital training and employment has a greater effect on social entrepreneurship, whereas spending on R&D would have a greater effect on general entrepreneurship. The income distribution would have a more or less similar effect in both cases.

Conclusions and discussionEntrepreneurship is one of the variables chosen to analyze the factors that stimulate economic growth. Increased awareness of environmental problems has led to an alteration in the objective to be achieved, introducing analysis of the effects of entrepreneurship on sustainable development. In this area, the role of the social entrepreneur in this relationship has also been considered.

Due to the positive relationship between both types of entrepreneurship on sustainable development, it is important to try to find out who has the greatest impact on sustainable development and what the factors are that stimulate this entrepreneurial activity by grouping these factors into two main groups: sociocultural and economic.

To achieve this objective, an empirical analysis has been carried out for the case of 15 OECD countries that shows the following results: Both types of entrepreneurial activity, general and social, stimulate sustainable development, although the impact of general entrepreneurship is greater than is that of social entrepreneurship. From this perspective, measures aimed at stimulating entrepreneurial activity would indirectly favor the achievement of greater sustainable development.

Taking this result into account, it is necessary to consider the role played by the factors in favoring entrepreneurship. The results obtained show that both groups of factors are positively related to the two types of entrepreneurship analyzed, but the sociocultural factor shows a greater impact than does the economic one. Faced with this common result, it should be noted that the weight of the indicators is different depending on the type of entrepreneur. In the case of general entrepreneurship, the proper functioning of institutions and the control of corruption show a greater effect, and in the case of social entrepreneurship the control of corruption and measures aimed at education and health have a higher effect. This implies that in both cases, measures aimed at controlling and improving the behavior of institutions aimed at reducing corruption would have a beneficial effect.

Regarding economic factors, spending on gross fixed capital training and employment have a greater effect on social entrepreneurship, whereas R&D and unemployment show a high impact on general entrepreneurship. Income distribution shows a similar effect in both cases.

Therefore, public sector actions aimed at stimulating entrepreneurship can have different effects on both types of entrepreneurship. Policies aimed at promoting human capital, employment, and investment aid would favor more social entrepreneurship, whereas those that increase innovation and improve institutions and are aimed at reducing corruption and making the market freer and more effective would have a greater impact on general entrepreneurship. On the other hand, redistributive policies aimed at improving income distribution would have a similar impact on both types of entrepreneurship.

This study is subject to improvement by introducing more countries in the sample to compare the situation of countries with different structures. Likewise, as statistical information improves, it would be convenient to introduce more variables within the factors considered, especially those with an environmental nature, with particular focus on the role of green innovations in the process.