Education is an important tool used to equip knowledge and pursue self-improvement, which may affect intergenerational social class mobility through human capital accumulation. Using 8014 mixed cross-section samples from the 2017, 2018 and 2021 China General Social Survey (CGSS), an multi-nominal logistic regression model was adopted to empirically analyse the impact of educational levels on intergenerational social class mobility in China. The econometric results indicated that (1) higher education considerably promotes subjective and objective upwards intergenerational social class mobilities, with the objective effect exceeding the subjective effect by 3.4 %; (2) the implementation of the compulsory education law and the expansion of higher education enrolment has increased the potential for high educational level to drive upwards intergenerational social class mobility; (3) among the different types of education, population migration exerts a repelling effect on objective upwards intergenerational social class mobility, whereas family background exerts a negative effect on subjective intergenerational social class mobility; and (4) the effects of education on intergenerational social class mobility are heterogeneous, with women, non-agricultural hukou holders and groups in developed areas facing greater difficulties in achieving social mobility through education. The main contribution of this study is its initial detection of the varying impacts of educational level on intergenerational social class mobility, as investigated through subjective and objective perspectives.

The debate between ‘studying being useless’ and ‘knowledge changing fate’ (Beltran Tapia & de Miguel Salanova, 2021; Gairal-Casadó et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2023) and between the anxiety of ‘successful people coming out of poor family’ and that of ‘successful people not coming from poor families’, to a large extent, addresses the issue of whether education can break down class solidification through the enhancement of knowledge. The educational scale in China has rapidly developed in recent years, e.g. the numbers of college graduates in 2003, 2010, 2020 and 2024 were 2.13, 6.31, 8.74 and 11.79 million, respectively. Meanwhile, the thinking paradigm of ‘expectations for their children’ portrays Chinese parents’ belief that the social class mobility facilitated by their offspring's education is an important path for breaking through class solidification and realising class leapfrogging. It is often argued that education is a catalyst for class mobility (Breen & Karlson, 2014; Carstensen & Emmenegger, 2023; Goldthorpe, 2014; Wolf, 2020), which is important for personal growth and promotion of social equity and justice. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that education plays a pivotal role in the acquisition and dissemination of knowledge. The educational process itself contributes to the development of critical thinking and problem-solving skills, which are important components for individuals to succeed in a complex social structure. In addition, education can democratise access to information and knowledge, potentially reducing information asymmetry and social inequalities. However, the impact of education on social class mobility is affected by multiple factors, such as inequitable opportunities owing to resource allocation and mobility heterogeneity owing to differences in the quality of education (Mulvey & Li, 2023). Therefore, it is necessary to interpret the impact of education on intergenerational social class mobility in China. Considering the related literature, scholars mainly conduct research on the different aspects of intergenerational mobility, the factors affecting intergenerational mobility and the influence of education on intergenerational social class mobility.

There is a large quantity of literature on intergenerational mobility, which mainly analyses from the perspectives of class, income, education and occupation. Some scholars interpret these by combining multiple dimensions. Regarding intergenerational social class mobility, Hertel and Groh-Samberg (2019) and DiPrete (2020), Toubol and Larsen (2017) argued that inter-class inequality and social mobility are correlated. Meanwhile, Bukodi and Paskov (2020) found that female class mobility is more impeded by class barriers than male class mobility, which are influenced by gender differences in the levels and patterns of intergenerational social class mobility. Sun et al. (2021) reported that there are differences in the level and trend of class and income mobilities in China and that class is generally likely to be a better measure of socio-economic status than current income. Regarding the intergenerational mobility of income, Yaish and Kraus (2020) as well as Chow and Guppy (2021) investigated the effect of intergenerational income mobility based on the intergenerational income elasticity index model proposed by Solon (1992). Chetty et al. (2014) and An et al. (2022) developed a nonlinear model to answer the question of the intrinsic correlation between offspring's income and parents’ income. Song et al. (2022) examined the dynamic intergenerational income disparities through life cycle by creating a comprehensive table of intergenerational income mobility. Regarding intergenerational educational mobility, Huq et al. (2021) investigated intergenerational educational mobility in Bangladesh and found that individuals experienced greater mobility in primary and secondary education than in higher education. Van der Weide et al. (2024) emphasised that the uneducated parents’ offspring were more likely to lack the means to receive better education, whereas the next generation of highly educated parents was more capable of maintaining the elite status of the family (Lin, 2020). Regarding intergenerational occupation mobility, Lissitsa and Chachashvili-Bolotin ((2023)) posited that the parents’ occupational status exerts a more determinative effect on the elucidation of the vocational preferences of their offspring than their educational level. Brunetti and Fiaschi (2023) found that the father being in the lower class has insufficient incentives for upwards mobility as per its offspring. In addition, some scholars compared indicators related to the different types of intergenerational mobility and investigated the interactions between these indicators. For example, Suárez-Arbesú et al. (2024) analysed education, occupational and income mobilities using the transmission matrix method by obtaining data from five countries in Africa. They found that education achieved the highest level of mobility and exhibited significant differences between countries. Tang (2023) explored the impact of education on intergenerational income mobility and found that upwards educational mobility was effective in blocking the transmission of intragenerational income gaps from the parent to the individual, whereas downwards educational mobility would exacerbate the intergenerational income transmission.

There are multiple complexities in the factors affecting intergenerational mobility, which could be mainly explored from the ascribed and the acquired aspects. In terms of individual ascribed factors, which usually include race, gender, age, parent's educational level and occupational status (Jha & Wharton, 2023; Lee & Mortimer, 2021; Scandone, 2022; Witteveen & Westerman, 2023), Lampard (2007) developed a logistic regression model using the data from the British Household Panel Survey and proposed that parents’ educational level and occupational category play a vital role in the offspring's acquisition of service position. The individual's acquired factors mainly include education, qualification, marriage, skill and job (Butratana & Trupp, 2021; Guo, 2022; Kourtellos et al., 2020). For example, Gronning and Kriesi (2022) pointed out that an individual's general skills and knowledge play a decisive role in long-term upwards mobility. Liu et al. (2023) argued that Internet skills explicitly affect class mobility. In addition, the macro-environment has an explicit impact on intergenerational mobility, such as the digital economy, marketisation process and policy regime (Xing et al., 2020). For example, Arun and Arun (2023) reported that digital jobs are typically associated with higher income levels and greater social mobility. Martindale and Lehdonvirta (2023) demonstrated that digital transformation of the labour market may reproduce differences in job opportunities and mitigate differences in employers’ choice of workers based on class selection. Lippényi and Gerber (2016) confirmed assumption of a distinctive state socialist mobility regime and argued that the state institution would generate quite different mobility patterns. Jackson and Evans (2017) compared social mobility patterns among 13 Eastern and Central European countries in the early 1990s with those in the late 2000s, which is the period of the transmission from socialism to capitalism. They found that there was a considerable decline in relative social mobility between these two periods, which is consistent with the findings of Zhou and Xie (2019) in China.

There are two attitudes of education affecting intergenerational social class mobility, namely, functional opinion and conflict opinion. Functionalism holds that educational level determines occupational height and social class and could perturb social class mobility by affecting individual skills (Kuha et al., 2021). Corresponding research also showed that education influences upwards intergenerational mobility (Deary et al., 2005; Duan et al., 2022; E. Bukodi & Goldthorpe, 2011; Johnson et al., 2010). Meanwhile, the effects of social class solidification and offspring education are not negligible (Song et al., 2016). In addition, the probability of upwards social class mobility is higher for the well-educated group than other groups, which was also demonstrated by Breen (2019). Those scholars with conflicting opinions suggested that education plays an instrumental role in reproducing social class, i.e. the ‘class solidification’ effect (Albrecht & Albrecht, 2010; Lindley & Machin, 2012). For example, Bourdieu (1984) introduced the theory of cultural capital reproduction, which stated that the cultural mechanism of class reproduction is the hidden intergenerational transmission within the family; this view shows that education enables the intergenerational transmission of class status, reinforcing the original unequal social structure (Wang, 2020). Jorrat et al. (2024) confirmed that the expansion of educational opportunities or the equalisation of educational access does not substantially contribute to intergenerational social mobility in urban Argentina. Remes (2022) found that educational level may contribute to the decline in middle class and the polarisation of classes in Finland. Salvanes (2023) stated that education is not a key factor in the success of adults in the labour market and that increasing the educational level of poor children cannot help to improve their performance in the labour market.

As reported by existing literature, most scholars focus on a single dimension of intergenerational educational mobility or social class mobility. However, this study took education as the main factor affecting class mobility and used the China General Social Survey (CGSS) database to develop the theoretical model. It explored the direct causality between education and class mobility from the perspective of absolute intergenerational mobility. Second, although some scholars have investigated the long-term impact of education on social class mobility by tracking data, they ignored the role of ‘education inflation’ in different historical periods. The present study divided the samples into three different groups according to the landmark events so that the results would be more possible. Third, scholars examined the objective class mobility and the subjective class identity separately, whereas the present study combined both to make a corresponding comparison and simultaneously examined the mediating and moderating effects of population migration and family background. The main contribution of this study is its empirical analysis of the heterogeneity of the impact of education on intergenerational social class mobility in the objective and subjective dimensions.

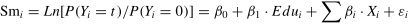

Model establishment and research hypothesisModel establishmentIntergenerational mobility usually has three types, namely, upwards mobility, intergenerational transmission and downwards mobility, which were used as explanatory variables in this study. Taking the values 0 and 1 and could not satisfy the definition of binary categorical variables. Hence, we used the multi-nominal logistic regression model (MLRM) (Yi & Yao, 2023), which is a model that uses unordered multi-categorical variables as explanatory variables. Its initial model is the following:

Here, t denotes three different types of intergenerational mobility patterns, and thus, Yt is set to own three values, −1, 0 and 1, which represent downwards mobility, intergenerational transmission and upwards mobility, respectively. As the MLRM needs to define a certain value as the benchmark in the regression analysis, this study used intergenerational transmission (i.e. Yt = 0) as the benchmark for comparative analysis. Considering that this study explores the impact of education on intergenerational social class mobility, it is necessary to add the variable of educational level and to introduce explanatory and control variables. Hence, Eq. (2) is expressed as follows:

Eq. (2) is the benchmark model for this study. Here, Mobilityi denotes the intergenerational mobility mode; Edui, the offspring's educational level, which is categorised into primary, secondary and higher education. We take secondary education as the benchmark and report the correlation coefficients of primary and high education; Xi denotes the control variable and εi represents the perturbation terms.

The modes of intergenerational social class mobility include the objective and subjective dimensions. As per the objective dimension, intergenerational social class mobility could be characterised in terms of the difference in socio-economic status between the offspring and the parents. It is mainly quantified by the socio-economic status index of an individual's position in the socio-economic structure, which could be measured by the average educational level and income (Iamtrakul et al., 2022; Tan et al., 2020). As per the subjective dimension, the factors affecting individual perceptions of class include educational level, income status, occupational status, family background, social network and welfare. Therefore, intergenerational social class mobility could be mainly obtained by comparing the class of the offspring with that of the father, so that differences in class identity and psychological factors lead to the heterogeneity of subjective class perceptions (Galvan et al., 2023; Melita et al., 2021; Moss et al., 2023). Accordingly, subjective and objective intergenerational social class mobilities exhibit significant differences for reasons of information asymmetry, social comparison and cultural factors. Thus, it is necessary to explore the impact of educational level on subjective and objective intergenerational social class mobilities, so Eq. (2) can be expanded to Eqs. (3) and (4):

Here, Omi and Smi denote the objective and subjective intergenerational social class mobility, respectively; these two models are used to analyse the subsequent mediating and moderating effects.

Research hypothesisOccupational status attainment is one of the most important indicators for measuring intergenerational mobility. Since Blau and Duncan (1967) proposed the status attainment model, educational level has been the main focus of research on status attainment (Bukodi & Goldthorpe, 2011; Hout, 1988). Education can improve individual knowledge or cognitive ability and help establish a wide range of social networks, achieving stronger competitiveness by accumulating human capital level (Schultz, 1961). Therefore, the individual would own more choices in the labour market, which is the key to obtaining high-income occupations and improving social status. In view of the actual situation, the acceleration of industrial transformation and artificial intelligence advancement led to higher requirements for the comprehensive quality of workers, making it more difficult for people with low educational level to realise the class leap. Higher education is an important initiative to realise the cross-domain of social classes. In fact, according to the signal screening theory (Spence, 1973) and the elite theory (Bühlmann et al., 2022), under the condition of information asymmetry, employers usually screen job applicants based on their education, which would help individuals with higher education to obtain higher positions and better treatment. Furthermore, a high educational level would be more convenient to obtain professional status, strengthen the possibility of upwards class migration and promote an upwards trend of intergenerational social class mobility. Therefore, hypothesis (H) 1 is proposed: Education enhances the probability of upwards intergenerational social class mobility, concurrently mitigating the propensity for stratification or descending mobility.

The impact of education on intergenerational social class mobility significantly varies across economic and social contexts (Mullins et al., 2021). For example, business cycle fluctuations in the economy exert a push-and-pull effect on the social class of workers (Becker et al., 2024). Social change and market fluctuations affect the enactment and implementation of education policies, which in turn lead to different occupational requirements for groups with the same educational level over time, implying that the market raises the corresponding education, creating skilled jobs and enhances the occupational distribution through skill-biased technological change (Jephcote et al., 2021; Rauscher, 2015). However, some scholars argued that there exists a non-synergistic interaction between social mobility and short-term fluctuations in the economic cycle or labour market (Trinh & Bukodi, 2022). In China, two policies, the enactment of the compulsory education law in 1986 and the expansion of higher education enrolment in 1999, have gained considerable attention, and Guo et al. (2019) found that these policies enhanced intergenerational educational mobility in urban areas but worsened that in rural areas. In addition, the depreciation of diplomas induced by education inflation leads to considerable heterogeneity in the impact of education on social class mobility (Gruijters, 2022). Therefore, H2 is proposed: In the dynamic context of economic and societal evolution, the impact of education on intergenerational social class mobility is characterised by a nonlinear pattern.

From the perspective of human capital, individuals with high skills and educational levels have greater initiative in selecting jobs, and there are strong correlations between them (Araki, 2023; Aver et al., 2021; Trinidad et al., 2023). In fact, those who attain higher education may exert a stronger push-and-pull effect on population migration (Hathaway, 1960), such as obtaining better jobs, better health care and better education for their children, to achieve the trend of outward migration or shifting to the city. From the perspective of economic and social development, cities tend to have high-quality resources, good security, benefit policies, etc., which foster talent convergence within the urban area. Based on the needs of their development, groups with middle and high educational levels would choose occupations with high social status and high opportunity potential; thus, a large number of high-quality people would move to cities or developed regions, forming a more obvious siphon effect (Luo et al., 2024). Based on the Todaro model, it is often assumed that anticipated remuneration in urban sectors or locales surpasses non-rural department or regions, and the inducing ratchet effect or psychological implication is inclined to allure individuals with advanced educational qualification to vie for positions with greater potential and tangible benefits. When an individual undergoes outward migration, their employment opportunities, sources of income and social security might be superior to the original level, which might prompt a higher probability of intergenerational social class mobility. Therefore, H3 is proposed: During the urbanisation process, population migration serves as a pivotal intermediate factor facilitating the impact of education on intergenerational social class mobility.

The educational levels attained by the offspring as well as the educational resources at their disposal is intricately associated with their familial background (Costa Filho & Rocha, 2022; Erikson, 2016). The well-established fact that high education and elite degrees are increasingly dependent on family background, particularly on parental financial resources, suggests that family background can have an explicitly moderating effect on the educational outcomes of children (Serediak & Helland, 2023; Yan & Gao, 2024). In turn, it would lead to a decline in intergenerational educational mobility, even generating education inequality (Davis-Kean et al., 2021). When the expansion of higher education increases, the repository of the social elite considerably expands, the signalling function of education declines, and the family background of origin would play a larger role, leading to ‘nepotism’, so that social status reproduction frequently occurs. Parents with strong backgrounds and high status have access to a wide range of social resources, and these could link their offspring to better employment opportunities (Toft & Friedman, 2021) and more stable careers (Toft, 2019). A relatively stable family background serves as a subtle mechanism for the offspring's perception of intergenerational social class mobility. In addition, fathers with high educational level are also likely to have high social class, resulting in their offspring's presentation of better cognitive ability and fewer personal behavioural problems (Cano, 2022; Ming et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020), which would also impact the perception of intergenerational social class mobility. Therefore, H4 is proposed: The enduring familial context operates as a clandestine determinant shaping the progeny's consciousness regarding the dynamics of intergenerational movement within the social hierarchy.

Data resource and index implementationData source and descriptionThis study used the CGSS database. The sample consisted of China's 31 provinces, autonomous regions, municipalities directly under the Central Government and special administrative regions. Since the occupation code used before 2016 in the CGSS is ISCO-88, but not the latest occupation code ISCO-08, therefore, the blended cross-sectional data consisting of the years 2017, 2018 and 2021 were selected as the data source. Considering the representation of the father in the family role, the information of the fathers was used to characterise the basic situation of the paternal generation (Donnelly et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2019). After excluding outliers and missing values, omitting those who have never been educated and who were unemployed and retaining the sample of 16–65-year-olds, the final sample sizes obtained in the years 2017, 2018 and 2021 were 3510, 3414 and 1946, respectively, which totals 8870. After converting the occupation codes of the father and the offspring to International Socio-Economic Index (ISEI) values, the total sample size obtained after adjustment was 8014 owing to the presence of unmatched samples.

Index implementationTable 1 presents five classifications regarding the selection, definition and assignment of variables, including dependent, independent, mediating, moderating and control variables.

Description of variables.

| Variable | Definition | Measurement method | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variable | Edu | Educational level of offspring | Primary education = 1Secondary education = 2Higher education = 3 |

| Dependent variable | Sm | Subjectiveclass mobility | Intergenerational upwards mobility = 1Intergenerational transmission = 0Intergenerational downwards mobility = −1 |

| Om | Objectiveclass mobility | Intergenerational upwards mobility = 1Intergenerational transmission = 0Intergenerational downwards mobility = −1 | |

| Control variable | Age | A person's age | Year of survey minus year of birth |

| Gender | Distinguishing between the sexes | Male = 1 Female = 0 | |

| Party | Political profile | CPC member = 1Non-CPC member = 0 | |

| Fedu | Level of paternal education | Primary education = 1Secondary education = 2Higher education = 3 | |

| Fparty | Paternal political profile | CPC member = 1Non-CPC member = 0 | |

| Mediating variable | Mig | Population migration | Migrated = 1 Not migrated = 0 |

| Moderating variable | Bac | Level of household economic capital | Well below average = 1Below average = 2Average = 3Above average = 4Well above average = 5 |

- (1)

Objective intergenerational social class mobility. This study used the ISEI to measure the social class of the father and the offspring. This index could measure an individual's objective socio-economic status owing to the combination of multiple factors for ranking and assignment (Ganzeboom & Treiman, 1996; Ganzeboom et al., 1992). The ISCO08 codes of the offspring's current occupation and the father's occupation at the age of 14 years were converted into ISEI values (Newlands & Lutz, 2024), and then the social classes were combined into three categories, i.e. the upper social class (ISEI greater than 61) was assigned the value of 2; middle social class (ISEI between 31 and 60), 1; and lower social class (ISEI less than 30), 0. The social class of the offspring was subtracted from that of the parent. A difference of over 0 between the two indicates an upwards intergenerational mobility and is assigned the value of 1. A difference of 0 indicates an intergenerational transmission and is assigned the value of 0. A difference of less than 0 indicates a downwards intergenerational mobility and is assigned the value of −1.

- (2)

Subjective intergenerational social class mobility. Drawing on the treatment made by Zhang et al. (2016), the question ‘In this current society, what level of society are you personally in?’ was used as a subjective class rating for the offspring, whereas the question ‘On which level do you think your family was at when you were 14 years old?’ was used as a subjective class rating for the father. The former scores were subtracted from the latter scores to produce a continuous variable, with values ranging from −9 to 9. Here, samples greater than 0 were categorised as upwards intergenerational mobility and assigned the value of 1, samples equal to 0 were categorised as intergenerational transmission and assigned the value of 0 and samples less than 0 were categorised as downwards intergenerational mobility and assigned the value of −1.

Educational level. Following the treatment made by Zhu and Zhang (2024), the respondents’ highest education in the original questionnaire could be divided into 11 levels; the samples that did not receive education were already deleted. ‘Elementary school’ was defined as primary education and assigned the value of 1, ‘junior high school, senior high school, vocational secondary school, technical school and vocational senior high school’ were defined as secondary education and assigned the value of 2 and ‘higher vocational college, bachelor's degree, master's degree and above’ were defined as high educational level and assigned the value of 3.

Mediating variablePopulation migration. The questions ‘What was your hukou registration status at birth?’ and ‘What is your current hukou registration status?’ were used. The difference between these two is characterised by assigning the value of 1 if the individual's hukou migrates and 0 otherwise.

Moderating variableLevel of household economic capital. The question ‘Where does your family's economic status fall in the locality?’ was used as the characterisation variable of household economic capital, which was divided into five grades, namely, ‘far below average’, ‘below average’, ‘average’, ‘above average’ and ‘well above average’ and assigned the values of 1 to 5, respectively.

Control variableThe age, gender and political profile of the offspring as well as the educational level and political profile of the father were included in the model as control variables. Among them, at the offspring level, the age variable was the year of survey minus the year of birth. The gender variable was assigned the value of 1 for the male and 0 for the female. The political profile variable was assigned the value of 1 for CPC members and 0 for non-CPC members. As for the aspect of the father, the assignment was done in the same manner as that of the offspring.

Descriptive analysisThe sample used in this study consisted of 8014 individuals, of whom 44 % were men and 56 % were women. The proportions of young (aged 16–34 years), middle-aged (aged 35–59 years) and elderly (aged 60 years and above) individuals were 40 %, 58 % and 2 %, respectively. In addition, the ratio of urban to rural participants was 37:63. The descriptive results of the main variables are presented in Table 2. The difference between the mean values of subjective and objective intergenerational social class mobilities was relatively small, approximately 40 %, the total intergenerational social class mobility rate was 64.97 % and the intergenerational transmission rate was 35.03 %, indicating that the current mode of intergenerational social class mobility in China mainly consists of upwards mobility and the overall degree of openness is relatively high. The mean value of educational level is 2.353, demonstrating that more than 90 % of the total samples have secondary and high education, indicating that China's current policy of 9-year compulsory education and the expansion of higher education have yielded good results, which implies that the educational level of the whole population has been effectively improved. In terms of population migration, approximately 25 % of the respondents have migrated their hukou, whereas the rest have rural hukou and have not migrated, suggesting that the current rate of population mobility and migration in China still needs to be improved. In terms of the level of household economic capital, more than 80 % are middle- or lower-income households, indicating that Chinese residents’ perception of household income level has not improved with the increase in per capita disposable income or the narrowing of the urban–rural income gap. In terms of the interaction term between the educational level and the level of household economic capital, the decentralised treatment is taken, with a minimum value of −1.702 and a maximum value of 2.357.

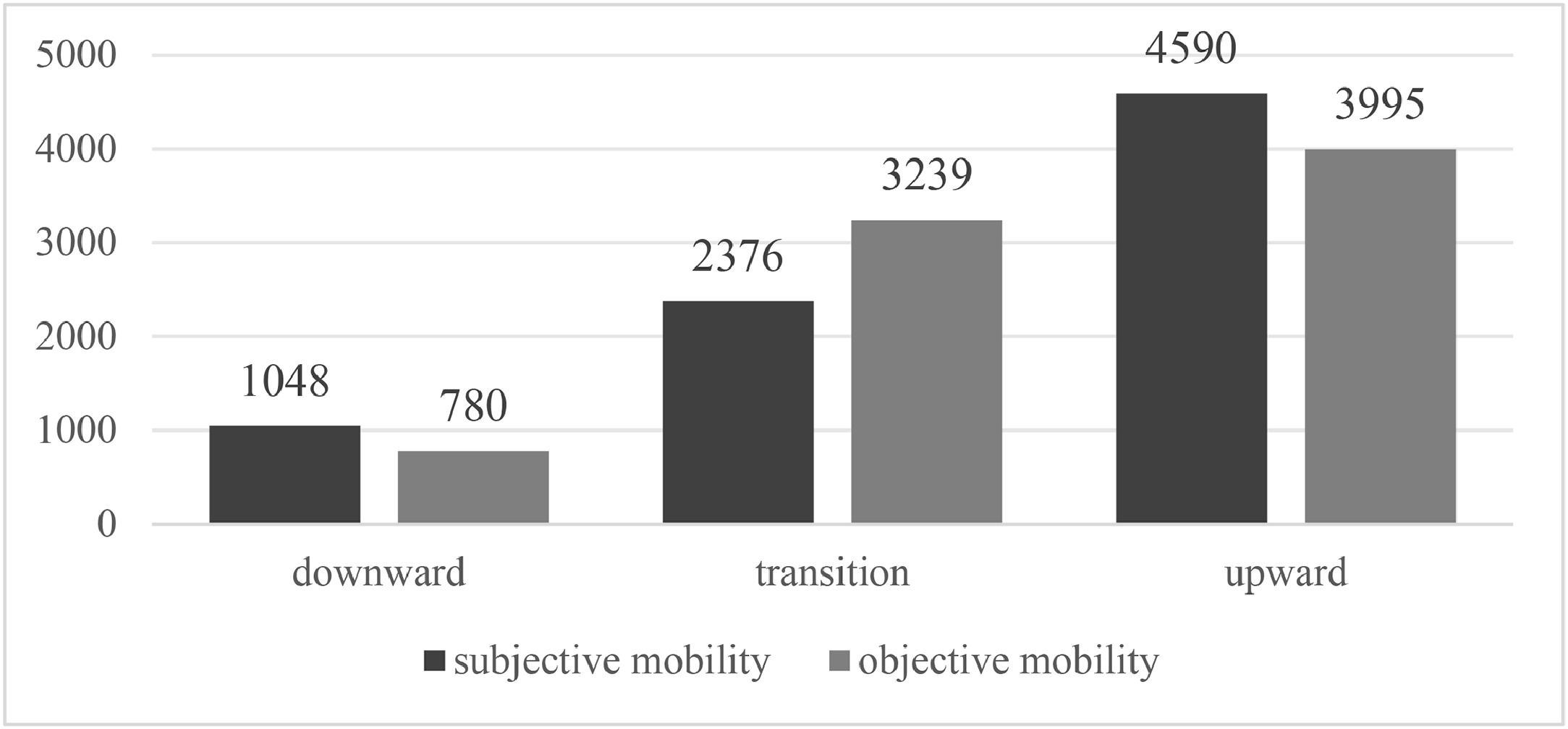

Now we turn to analyse the subjective and objective intergenerational social class mobility kernel density, with the detailed result presented in Fig. 1. From the objective perception, the kernel density curve of the father's social class is more distributed in the low level and decreases in a step-by-step manner, whereas the offspring's social class is concentrated in the middle level. From the subjective perception, the kernel density curve of the offspring's social class also tends to be concentrated in the middle level, which indicates that compared with the father's social class, the offspring's social class tends to be more intermediated. This demonstrates that the proportion of the lower-middle class remains, whereas that of the middle class increases, which is also in line with the current social class structure of China's ‘Tu’ shape. Comparing the subjective and objective intergenerational social class mobilities in Fig. 2, it can be inferred that, on the one hand, the trend of upwards intergenerational social class mobility is more obvious than that of intergenerational transmission or downwards mobility, and the subjective perception is larger, which might be related to the fact that individuals believe they could break through the class barriers to make the leap based on corresponding factors, such as the current social fairness and cultural system. On the other hand, the objective fact of downwards intergenerational mobility is lower than the subjective perception, indicating that although some respondents agree with the phenomenon of downwards social class mobility compared with their father, there has not been a substantial decline in objective socio-economic status, while opposite conclusion is observed in the sample of intergenerational transmission. For example, 30 % of the respondents perceived that there are basically no gap in class between the two generations, but class solidification might be actually quite serious. Overall, there is a significant deviation regarding subjective and objective intergenerational social class mobilities.

Empirical analysisTo systematically analyse the effect of educational level on intergenerational social class mobility, it is proposed to analyse the results of the main effect of educational level on intergenerational social class mobility from the aspects of baseline regression, the results of the mediating effect on objective dimension from the transmission mechanism of population migration, the results of the interaction in subjective dimension from the moderating effect of the family background and the results of heterogeneity from the three dimensions of gender, hukou and region and to report the results of the robustness test.

Baseline regression analysisThe MLRM could be used to predict the probability that an observation belongs to each category given the value of the independent variable. Most related studies usually used the year of education or education percentile to rank as a characterising variable for educational level (Azomahou & Yitbarek, 2021; Wu & Marois, 2024), while the present study adopted a different hierarchical treatment of year of education. Education is categorised into primary, secondary and higher education, with secondary education set as the benchmark to compare the impact of educational level differences on intergenerational social class mobility.

We used the MLRM to examine the effect of educational level on subjective and objective intergenerational social class mobilities, with the econometric results presented in Table 3. As discussed in the previous section, the estimation results of Eq. (2) were based on the benchmark of ‘intergenerational transmission’ to highlight the difference between upwards and downwards mobilities, and all of these add five control variables, including the offspring and father dimensions. To be consistent with the results of the robustness test, econometric results of the control variables are reported but not analysed for statistical significance. In contrast, in all other aspects of the econometric results, only whether control variables are taken or not is considered, but the econometric results are not reported. In particular, columns (1) and (2) report the effect of educational level on objective intergenerational social class mobility, whereas columns (3) and (4) report the effect on subjective intergenerational social class mobility.

Results of educational level on subjective and objective mobilities.

| (1) Objective downwards intergenerational mobility | (2) Objective upwards intergenerational mobility | (3) Subjective downwards intergenerational mobility | (4) Subjective upwards intergenerational mobility | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edu | P | −0.225 | −0.272** | −0.891*** | −0.005 |

| (0.259) | (0.009) | (0.000) | (0.960) | ||

| H | −0.249** | 0.277*** | −0.175** | 0.109* | |

| (0.011) | (0.000) | (0.046) | (0.072) | ||

| Age | 0.011** | −0.010*** | 0.003 | 0.008*** | |

| (0.009) | (0.000) | (0.336) | (0.001) | ||

| Gender | 0.019 | 0.154** | −0.071 | 0.029 | |

| (0.819) | (0.002) | (0.345) | (0.573) | ||

| Party | −0.087 | 0.172** | −0.038 | 0.368*** | |

| (0.461) | (0.019) | (0.743) | (0.000) | ||

| Fedu | 0.684*** | −0.701*** | 0.134** | −0.283*** | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.042) | (0.000) | ||

| Fparty | 0.510*** | −0.676*** | 0.400*** | −0.222** | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.002) | ||

| _cons | −3.108 | 1.590 | −1.118 | 0.711 | |

| N | 8014 | 8014 | |||

Note: (1) P-values in parentheses; (2) *, ** and *** indicate passing 10 %, 5 % and 1 % significance tests, respectively; (3) the following takes the same treatment.

As can be seen from Table 3, individual educational level is an important variable that affects intergenerational social class mobility. Specifically, columns (1) and (2) show that primary education decreases the probability of affecting objective upwards intergenerational social class mobility by 1.31 (here, it is e0.272) and higher education increases by 1.32 (here, it is e0.277) compared with intergenerational transmission. This indicates that individuals with higher education have a higher probability of upwards class mobility and a lower probability of downwards class mobility or class entrenchment. Combined with the marginal effect shown in Table 4, if other variables are constant, compared to the benchmark of secondary education, primary education leads to an increase in the probability of objective intergenerational transmission by 6.3 % and a decrease in the probability of upwards mobility by 5.3 %, but higher education leads to a decrease in the probability of objective downwards intergenerational mobility by 3.1 %, a decrease in the probability of intergenerational transmission by 4.2 % and an increase in the probability of upwards intergenerational mobility by 7.3 %, which implies higher education is associated with higher mobility (Ojalehto et al., 2023).

Furthermore, comparing columns (3) and (4) with columns (1) and (2), it can be observed that the estimated coefficients are in the same direction between the subjective and the objective perceptions. The above results not only imply that the effect of educational level on subjective social class mobility is further corroborated by the objective perception but also that individuals with high educational level are more subjectively inclined to experience upwards intergenerational social class mobility compared with intergenerational transmission. For example, in Table 4, high educational level leads to a 2.8 % decrease in the probability of subjective downwards intergenerational mobility, a 1.1 % decrease in the probability of intergenerational transmission and a 3.9 % increase in the probability of upwards intergenerational mobility. The comparison shows that educational level has a greater impact on the objective than on the subjective dimension, which might be related to the fact that the factors affecting the perception of intergenerational social class mobility are more complex and that it is difficult to precisely highlight the role of education (Friedman et al., 2021). The combined econometric results indicate that high educational level has the advantage of enhancing upwards intergenerational social class mobility, which indicates that individuals are empowered by access to quality education resources, thereby increasing their chances of being in the higher class. Hence, H1 is partially verified.

To explore the differential effects of educational level on upwards intergenerational social class mobility in different historical periods in China, based on the study by Guo et al. (2019), the enactment of the compulsory education law in 1986 and the expansion of higher education enrolment in 1999 were taken as the landmark events for touching an important effect on educational level. At the same time, ‘What year did you obtain your highest degree?’ is divided into three stages: before 1986 for Stage I, 1986–1999 for Stage II and after 1999 for Stage III, with assigned values of 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Furthermore, the educational level of the same cohort is controlled to enhance comparability. The econometric results indicate that downwards intergenerational mobility is not significant enough to be statistically analysed. Thus, the results of the subjective and objective upwards intergenerational social class mobilities are retained, with the detailed result presented in Table 5.

Econometric results for the elimination of education inflation.

| Stage I | Stage II | Stage III | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Objective upwards mobility | (2) Subjective upwards mobility | (3) Objective upwards mobility | (4) Subjective upwards mobility | (5) Objective upwards mobility | (6) Subjective upwards mobility | |

| Primary | −0.261* | −0.040 | −0.197 | 0.095 | −0.800** | −0.337 |

| (0.095) | (0.804) | (0.274) | (0.630) | (0.014) | (0.311) | |

| High | 0.480 | 0.437 | 0.434** | 0.335** | 0.328*** | 0.130 |

| (0.115) | (0.163) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.000) | (0.123) | |

| Age | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gender | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Party | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Fedu | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Fparty | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| _cons | 1.272 | 0.866 | 1.030 | 0.471 | 0.623 | −0.118 |

| N | 1444 | 2312 | 4258 | |||

After removing the inflationary effect of education, implementations of both policies significantly influence the effect of high educational level on upwards class mobility at the objective level, and the estimated coefficients are considerably larger. In Stage I, which is before the enactment and implementation of the compulsory education law, educational level does not substantially affect the subjective and objective upwards intergenerational social class mobilities, probably because receiving education requires a large amount of financial resources, which hinders or even deprives the offspring's right to receive an equal education (Liu & Lei, 2023) to a certain extent. In Stage II, which is the period from the enactment of the compulsory education law to that of the expansion of higher education enrolment, primary education does not have a considerable effect. On the one hand, it might be because the policy of completing the 9-year compulsory education for all school-age children has not been fully implemented in China, particularly in the rural areas. On the other hand, the offspring who receive higher education are more likely to move to higher strata of the hierarchy and subjectively agree with the existence of a breakthrough between generations; thus, higher education is more effective in promoting upwards social class mobility in the subjective and objective dimensions than secondary education (Li et al., 2023). In Stage III, which is after the expansion of higher education enrolment, the advantageous impact of higher education on upwards class mobility exhibited a downwards trend, suggesting that the expansion of higher education enrolment enhances the probability of upwards intergenerational social class mobility by increasing the opportunities of college enrolment. However, it leads to the problem of mismatch of supply and demand in the labour market, which results in lower high education returns, makes it more difficult to obtain suitable occupations and rewards than those with the same degree before the expansion and induces its function to relatively decline due to the high level of education (Ou & Hou, 2019); thus, the estimated coefficient of upwards intergenerational mobility in Stage III is lower than that in Stage II. In terms of subjective perception, the expansion of higher education enrolment enabled the offspring to obtain more employment opportunities by improving educational level, which indicates the increasing difficulty for the disadvantaged class to break through the social class reproduction by upgrading their academic qualifications. Moreover, the obstacles for their offspring in realising class-crossing are also increasing, thereby presenting a sharp decline or even becoming nonsignificant effects. Therefore, H2 is verified.

Analysis of the mediating effectThe mediation effect follows the KHB mediation effect test proposed by Kohler et al. (2011). The KHB test has the advantage of satisfying the ‘continuous omission assumption’ and has been widely employed to assess the mediating variables in the MLRM. The econometric result indicated that population migration did not pass the significance test as per the effect of educational level on objective downwards intergenerational social class mobility; thus, the result was not reported. The econometric results are presented in Table 6.

After decomposition using the KHB analysis method, the result indicated that education is an important factor influencing population migration, which is consistent with the findings of Zou and Deng (2022). Specifically, the effects of high education on objective downwards intergenerational mobility are all positive, whereas the effects of primary education are all negative. It can be considered that population migration is an important transmission mechanism in the effect of educational level on objective intergenerational social class mobility, and high education can effectively promote population migration, hence realise upwards intergenerational social class mobility. On the one hand, receiving higher education can improve skills, knowledge and income, thereby promoting individuals to migrate to economically developed areas with more employment opportunities, whereas receiving primary education makes it difficult to meet the diversified demand for high-skill jobs; thus, it exerts a significant negative effect on population migration. On the other hand, high educational level can effectively link the social network to help individuals obtain larger information resources and more extensive job opportunities in the process of choosing to migrate, thereby promoting upwards mobility of intergenerational strata. Meanwhile, for groups with a primary education level, the migration may destroy their original social links and support systems and even solidify the existing environment; hence, primary educational level does not exert a positive effect on upwards intergenerational mobility. Therefore, H3 is verified.

Analysis of the moderating effectThe econometric result of the moderating effects is presented in Table 7, where columns (1) and (2) are the original total effects without interaction term and columns (3) and (4) are the moderating effects with interaction term. After adding the interaction term, in subjective upwards intergenerational social class mobility, the regression coefficient of the interaction term is −0.167, and the regression coefficient of higher education decreases to 0.051, which shows that family background negatively alleviates the effect of educational level on subjective upwards intergenerational social class mobility. That is, the stronger the family background, the weaker the effect of educational level on upwards intergenerational social class mobility, and this is particularly significant in high educational level. This could be attributed to the complexity and variability of subjective identity. Excessive family involvement in the education of offspring is also detrimental to the advantageous role of education in promoting upwards class mobility. From another perspective, strong economic support in the family could reduce the pressure on education, so they are not worried much about the rate of return to education, thereby reducing the urgency of educational level in improving social status. Therefore, H4 is verified.

Econometric results of the moderating effect.

| (1) Subjective downwards intergenerational mobility | (2) Subjective upwards intergenerational mobility | (3) Subjective downwards intergenerational mobility | (4) Subjective upwards intergenerational mobility | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edu | Primary | −0.891*** | −0.005 | −0.938*** | −0.131 |

| (0.000) | (0.960) | (0.000) | (0.253) | ||

| Higher | −0.175** | 0.109* | −0.148* | 0.051 | |

| (0.046) | (0.072) | (0.097) | (0.405) | ||

| Bac | −0.140** | 0.401*** | |||

| (0.011) | (0.000) | ||||

| Edu*Bac | 0.019 | −0.167** | |||

| (0.845) | (0.010) | ||||

| Age | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Gender | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Party | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Fedu | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Fparty | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| _con | −3.108 | 1.590 | −0.772 | −0.316 | |

| N | 8014 | 8014 | |||

To test the robustness of the MLRM results, we employed a replacement model in which the explanatory variables were treated as ordered multicategorical variables. Consequently, we calculated the model using the Ordered Logit Regression Model (OLRM). This model is generally applied to continuous variables. Table 8 presents the results of the robustness test. Based on the significance level, as per the direction, and the significance of the explanatory variables, the results of the OLRM are generally consistent with those of the MLRM, which verifies the robustness of the latter. Hence, it further validates relevant research hypotheses.

Econometric results of the robustness test.

| (1) Objective downwards intergenerational mobility | (2) Objective upwards intergenerational mobility | (3) Subjective downwards intergenerational mobility | (4) Subjective upwards intergenerational mobility | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edu | Primary | −0.100 | −0.243** | −0.888*** | 0.198* |

| (0.605) | (0.016) | (0.000) | (0.053) | ||

| High | −0.382*** | 0.320*** | −0.247** | 0.162** | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.002) | (0.003) | ||

| Age | 0.015*** | −0.012*** | −0.002 | 0.007** | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.609) | (0.002) | ||

| Gender | −0.053 | 0.151** | −0.091 | 0.051 | |

| (0.505) | (0.002) | (0.180) | (0.276) | ||

| Party | −0.166 | 0.187** | −0.285** | 0.380*** | |

| (0.144) | (0.007) | (0.006) | (0.000) | ||

| Fedu | 1.006*** | −0.825*** | 0.316*** | −0.325*** | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

| Fparty | 0.795*** | −0.787*** | 0.539*** | −0.356*** | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||

| N | 8014 | 8014 | 8014 | 8014 | |

The econometric results indicate that the coefficients on subjective intergenerational social class mobility are insignificant for both male and female in terms of educational level; hence, only the objective intergenerational mobility results were reported, as detailed in Table 9. From the female perspective, primary education is negatively associated with objective intergenerational social class mobility, and high educational level is only significant in terms of objective downwards intergenerational social class mobility, suggesting that the female receiving primary education is more likely to have a higher chance of intergenerational transmission than mobility, and female receiving higher education faces the same crisis of class entrenchment. This implies that high educational level neither induces downwards class mobility of the female's offspring nor offers more opportunities for upwards mobility (Siddiqui & Shokeen, 2024). From the male perspective, the model is generally weak, with only the effect of high education on objective upwards intergenerational social class mobility passing the significance test, implying that the male's offspring is more likely to improve qualification through higher education and thus gain opportunities for class leapfrogging. This could be attributed to the ‘boy preference’ of the Chinese culture and gender discrimination in the labour market, which results in a male bias in the investment of education; thus, the male's offspring has more education resources to improve their educational level (Huo, 2021). Generally, as regards the promotion of upwards intergenerational social class mobility through high educational level, the problem of gender inequality is relatively obvious for female compared with male in China (Nivedita, 2024; Wang, 2021), e.g. female class mobility is more likely to experience ‘bottom persistence’, whereas male class mobility is more likely to experience ‘top persistence’.

Econometric results of gender heterogeneity.

| The female | The male | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Objective downwards intergenerational mobility | (2) Objective upwards intergenerational mobility | (3) Objective downwards intergenerational mobility | (4) Objective upwards intergenerational mobility | ||

| Edu | Primary | −0.477* | −0.323** | 0.002 | −0.218 |

| (0.094) | (0.029) | (0.993) | (0.134) | ||

| High | −0.510*** | 0.110 | −0.044 | 0.394*** | |

| (0.001) | (0.212) | (0.731) | (0.000) | ||

| Age | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Gender | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Party | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Fedu | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Fparty | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| _cons | −2.904 | 1.874 | −3.240 | 1.592 | |

| N | 3503 | 4511 | |||

The econometric results of subjective and objective downwards intergenerational social class mobilities did not pass the significance test; hence, only the upwards intergenerational social class mobility measures were reported (Table 10). Comparing the estimated coefficients in columns (1) and (3) for objective upwards intergenerational mobility, it was found that the effects of primary and higher education were opposite and that the coefficient of higher education on upwards intergenerational social class mobility of the rural hukou group reached 0.606, which is significantly larger than that of the non-rural hukou group. This could be attributed to the fact that the increased space for upwards social class mobility of the rural population would have a crowding-out effect on the upwards mobility of the urban population. Moreover, the expansion of higher education enrolment and the mass development of high education would help rural children achieve upwards class mobility through high education, which may lead to a greater impact of high education on objective upwards intergenerational mobility; the econometric results prove this point.

Econometric results of hukou heterogeneity.

| Non-rural hukou group | Rural hukou group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Objective upwards intergenerational mobility | (2) Subjective upwards intergenerational mobility | (3) Objective upwards intergenerational mobility | (4) Subjective upwards intergenerational mobility | ||

| Edu | Primary | −0.177 | 0.248 | −0.358** | −0.091 |

| (0.421) | (0.284) | (0.003) | (0.469) | ||

| High | 0.435*** | 0.171** | 0.606*** | 0.097 | |

| (0.000) | (0.035) | (0.000) | (0.360) | ||

| Age | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Gender | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Party | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Fedu | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Fparty | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| _cons | 1.400 | 0.664 | 0.939 | 0.638 | |

| N | 4457 | 3557 | |||

As regards the divisions of the National Bureau of Statistics of China, the 31 provinces were defined as follows: the eastern region includes Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong, Guangdong, Hainan and Liaoning; the middle region includes Shanxi, Anhui, Jiangxi, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Jilin and Heilongjiang; and the western region includes Inner Mongolia, Guangxi, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Tibet, Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia and Xinjiang. The sample sizes for the eastern, central and western regions in this study were 4622, 2063 and 1329, respectively, accounting for 58 %, 26 % and 16 % of the total sample. According to the 2024 national population statistics, the population proportions of China's eastern, central and western regions were 42 %, 30 % and 28 %, respectively, which are consistent with the sample structure used in this study. As most econometric results of regional heterogeneity passed the test, whether variability exists between regions needs to be determined. Hence, to match the results of hukou heterogeneity, only those of the impact of educational level on subjective and objective upwards intergenerational mobilities were reported (Table 11).

Econometric results of regional heterogeneity.

| The eastern | The middle | The western | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Objective upwards mobility | (2) Subjective upwards mobility | (3) Objective upwards mobility | (4) Subjective upwards mobility | (3) Objective upwards mobility | (4) Subjective upwards mobility | ||

| Edu | Primary | −0.178 | 0.026 | −0.392** | −0.251 | −0.339 | 0.424 |

| (0.226) | (0.866) | (0.033) | (0.185) | (0.164) | (0.133) | ||

| High | 0.293*** | 0.142* | 0.365** | 0.237* | 0.471** | 0.198 | |

| (0.000) | (0.074) | (0.002) | (0.061) | (0.002) | (0.204) | ||

| Age | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Gender | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Party | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Fedu | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Fparty | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| _cons | 1.376 | 0.625 | 1.419 | 0.533 | 1.879 | 0.566 | |

| N | 4622 | 2063 | 1329 | ||||

Similar to the results of hukou heterogeneity, the impact of primary education on upwards intergenerational social class mobility in different regions basically fails the significance test, whereas the impact of higher education on upwards intergenerational social class mobility shows a slowing down trend of ‘higher in the west and lower in the east’. The result implies that the higher the level of economic development of the region, the weaker the effect. In fact, the results of hukou heterogeneity also indicate that the impact of higher education on the rural hukou group is more obvious than non-rural hukou group, and that the ratio of the rural population in the less-developed region is higher than that in the developed region, which could explain why the effect of upwards intergenerational social class mobility is the highest in the western region than eastern and middle region. Moreover, it indicates that the result of regional heterogeneity is consistent with the result of hukou heterogeneity.

DiscussionBased on the CGSS, the blended cross-sectional data consisting of the years 2017, 2018 and 2021 were selected, a MLRM was developed, and the corresponding theoretical hypotheses were proposed to empirically analyse the impact of educational level on intergenerational social class mobility. The results are basically consistent with the four hypotheses. The findings obtained from this study were as follows: (1) The marginal-effect probability of high education augmenting objective upwards intergenerational social class mobility increased by 7.3 %, whereas the likelihood of primary education expediting subjective downwards intergenerational social class mobility increased by 8 %. (2) The treaty explores the disparate impacts of the compulsory education law and the expansion of higher education enrolment through the use of grouped regression analysis. The findings indicate that enactment of the compulsory education law enhances the likelihood of upwards intergenerational social class mobility by a factor of 1.54 and that its objective efficacy substantially surpasses the corresponding subjective perceptions. (3) High educational level exerts a positive effect on objective intergenerational social class mobility through the intermediary mechanism of population migration. However, the involvement of family background exerts a negative impact on subjective intergenerational social class mobility, with the estimated coefficient decreasing to 0.051. (4) The impact of educational level on intergenerational social class mobility exhibits heterogeneity across gender, hukou and region. Compared with men, women experience a hindrance in upwards intergenerational social class mobility, although they try their best to improve academic qualification; the non-rural hukou group, in contrast to the rural hukou group, faces issues of social class stratification owing to a crowding-out effect. Furthermore, the effect of high educational levels on intergenerational social class mobility in China is higher in the west and lower in the east, with the results of heterogeneity in hukou status aligning with the regional differences.

Notably, the research findings provide a new perspective for understanding the impact of education on social mobility, which is instrumental in the formulation of more effective educational policies. However, it is still worthwhile to further explore the following aspects.

The first aspect is the expansion of the time series. Owing to the problem of updating occupation codes and questionnaires, data within 3 years is utilised to form a mixed cross-section, but there is an obvious time effect of intergenerational social class mobility. Factors such as the macro-regulation of social policies, evolution of the economic situation and adjustment of opportunities for education and training can cause the nature and extent of intergenerational social class mobility to change accordingly over time, leading to varying results at the cross-sectional level (Nennstiel, 2021; Symeonaki & Stamatopoulou, 2020). Therefore, extending the survey period and dividing the samples and comparing them by period would make it possible to more comprehensively analyse the long-term effects of educational level on intergenerational social class mobility.

The second aspect is the comparison of policy enactment. In this study, cross-sectional data were used, not panel data, and there were no individuals with repeated observations at different time points, which might result in the inability to define the treatment and control groups before and after the policy enactment (Corral & Yang, 2024; Gu et al., 2022; Suk, 2024). Hence, this study employed grouped regression to examine the heterogeneous effects of educational level on intergenerational social class mobility. Therefore, using a multi-period difference-in-differences approach to assess the impact of a specific policy or treatment on a particular group would allow for a more rational analysis of how policy implementation and historical cycles affect class mobility. This can be achieved by examining the results of the average trend effect test.

The third aspect is the supplementation of research methods. As this study mainly utilised statistical data for empirical analysis, future research would indeed benefit from additional qualitative and case studies to validate the conclusions. Exploring personal stories, understanding how educational level influences intergenerational social class mobility and analysing the experiences and strategies of individuals are excellent approaches. This would undoubtedly enrich and expand the scope of our research conclusions.

RecommendationsEducation is a primary tool for breaking down the solidification of social classes and a significant driver of social mobility. The government should provide equal educational opportunities for all students by improving the allocation of educational resources, reforming the educational evaluation system and optimising social policies. Based on the findings of this study, the following policy recommendations are proposed.

Improve the allocation of educational resources. Analysis of household registration heterogeneity revealed that higher education has a greater impact on the upwards intergenerational social class mobility of the agricultural household group than primary education. This indicates a greater need for quality educational resources in rural areas to help rural children achieve social mobility through education. The government should increase investment in rural education, improve the hardware facilities of rural schools, increase teacher salaries, attract excellent teachers to teach in rural areas and ensure that rural students have the same educational opportunities as urban students.

Establish a diverse educational evaluation system. The study suggests that after the expansion of higher education, the relative impact of higher education has decreased, suggesting that the issue of ‘educational inflation’ is becoming increasingly prominent. The government should reform the educational evaluation system, move away from an overemphasis on academic credentials and establish a diversified evaluation system that focuses on students’ overall quality and abilities, such as innovation, practical and communication skills, to avoid over-reliance on academic qualifications as the sole criterion for talent assessment.

Improve the social assistance system. Family economic condition is an important factor affecting children's education. The government should improve the assistance system to provide financial aid to low-income families, helping them alleviate the economic pressure of educating their children. Considering the difficulty and scope of implementation, the government can prioritise addressing the issue of equal educational opportunities for children from poor families, preventing the excessive concentration of educational resources in few high-quality private schools.

CRediT authorship contribution statementBingqiang Li: Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Wenjie Nie: Methodology, Data curation. Xuan Zuo: Validation, Funding acquisition. Heping Zuo: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology.

This study was supported by the National Education Scientific Plan of China under Grant No. CFA230295.