This study aims to identify the roles played by firm flexibility (FLEX) in the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation (EO) and firm growth (FG) under different market conditions. In particular, it tests the mediating and moderating roles of FLEX, along with the moderating role of market conditions regarding FLEX. This is a longitudinal study that examines entrepreneurial behaviors during the pandemic crisis and afterwards. The sample represents small companies operating in the printing industry in Poland (150 surveyed during the crisis, and 145 afterward). The study uses structural equitation modeling. The results confirm the positive impact of EO on FG and show the positive impact of EO on FLEX regardless of market conditions. The role of FLEX varies along with changes in market conditions. Specifically, FLEX impacts FG and mediates the EO→FG relationship in a stable market, whereas it does not impact FG nor mediate the EO→FG relationship in a hostile market. Concurrently, FLEX moderates the EO→FG relationship in a hostile environment yet does not in a stable market. The significance of the differences in the strengths of the considered effects (moderation or mediation during the individual periods) are confirmed with a statistical test. This observation unveils that market conditions moderate the role of FLEX regarding the EO→FG relationship. With its findings, this study contributes to the literature on entrepreneurship and small and medium enterprises as well as FG.

Businesses are increasingly being exposed to crises or disasters, both human-made and natural; the recent COVID-19 pandemic was one of the worst global disasters in history (Dhir et al., 2024). Dynamism, turbulence, uncertainty, risk, complexity, and irregularity describe the contemporary business world's challenges of organizational performance (Awais et al., 2023). Current strategies must cope with ensuring an organization's success in light of different forms of turbulence, including environmental, organizational, political, societal, and technological (Hawk et al., 2024).

Creating appropriate strategies is the basis for companies to be able to seize new opportunities as well as achieve and maintain competitive advantages in ever-changing markets. When combined with innovation, strategic entrepreneurship is an effective response to variability, providing opportunities to adapt and change by using advantages and exploring opportunities in markets (Coccia, 2022).

A key construct in the strategic management and entrepreneurship literature is entrepreneurial orientation (EO), one of the best-established concepts in the management literature (Wales et al., 2021). EO focuses on new entry and value creation because it encompasses entrepreneurial decisions and actions aimed at achieving competitive advantage (Puumalainen et al., 2023). Previous studies have repeatedly referred to the impact of entrepreneurial orientation on performance (Alshahrani, & Salam, 2024; Hernandez-Perlines et al., 2021), firm growth (FG) (Eshima & Anderson, 2017; Sorama & Joensuu-Salo, 2023), and business success (Chen & Lin, 2019), which provides a solid theoretical base in this research area.

EO reflects firm behaviors that are associated with the pursuits of opportunities, such as risk-taking, innovativeness, proactiveness, competitive aggressiveness, and autonomy (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Miller, 1983). As companies operate in a highly changing environment, they must continuously adapt to new conditions; this also refers to their entrepreneurial behaviors focused on their pursuits of opportunities. Their abilities to adapt to their environment are expected to determine their entrepreneurial performance. This is explained, to some degree, by proactiveness, which reflects alertness and adaptability to market trends (Dess & Lumpkin, 2005). However, flexibility (FLEX; as a separate factor) can significantly affect entrepreneurial performance; in particular, evidence has shown the impact of FLEX on innovation performance (Yu et al., 2022) and corporate performance (Adomako & Ahsan, 2022; Chahal et al., 2019; De Clercq et al., 2014; Rundh, 2011; Welter, 2011). FLEX is an important element in the functioning of not only large companies but also small and medium enterprises (SMEs) (Adomako & Ahsan, 2022) as these are more sensitive to a rapidly changing environment compared to other types of businesses (Sharma et al., 2023). Thus, FLEX can enhance SMEs’ turnover and employment (Sen et al., 2023) and, as a result, their growth (Matalamäki & Joensuu-Salo, 2021). Dayan et al. (2022) confirmed that strategic FLEX is key for startups for achieving specific growth goals (Adomako & Ahsan, 2022; Daradkeh & Mansoor, 2023). Finally, a positive relationship exists between FLEX and business performance (Jain et al., 2013; Vokurka & O'Leary-Kelly, 2000; Yu et al., 2015).

Research has focused on FLEX and entrepreneurship and their roles in enhancing firm performance; this includes firm growth (which is a key indicator of a company's business performance and market success) (Chistov et al., 2023). However, the effect of FLEX is not clear; with regard to the EO–performance relationship, it can play the role of moderator (Chahal et al., 2019; Daradkeh & Mansoor, 2023; De Clercq et al., 2014;) or mediator (Hensellek et al., 2023; Kurniawan et al., 2019) as well as of antecedent of the EO itself (Chaudhary, 2019). This inconsistency regarding the role of FLEX in the entrepreneurial context constitutes the research gap behind this study.

To explain this inconsistency, this study considers the impact of market conditions. As stated before, environmental dynamism makes the business landscape turbulent; consequently, companies operate under different market conditions (which change frequently). Market conditions impact company operations as well as performance. Dynamic environment characteristics such as market and technological turbulence or aggressive competition can affect market deterioration or resource advantages (Zahoor & Adomako, 2023). In turn, environmental hostility forces companies to act in short-term perspectives focused on survival when their managers must meet the requirements of high business competition, a lack of prospects for long-term and rapid growth, and a lack of key organizational resources (García-Sánchez et al., 2021). Entrepreneurship research also investigates external conditions as determinants of EO and performance (see, e.g., Kreiser et al., 2020; Rosenbusch et al., 2013). In this area, clear explanations of these mutual relationships are also missing; this constitutes another research gap that the current study aims to address. We assume that the impact of market conditions is complex; that is, market conditions can also affect the roles of the particular factors that determine performance (in addition to their direct impact on performance). Therefore, this study investigates the impact of market conditions on the role of FLEX in the relationship between EO and performance. Consequently, we conduct research under different market conditions (during and after the crisis) to address research gaps related to the role of FLEX and market conditions in the entrepreneurial context.

In particular, this research aims to determine the role of FLEX in the EO–FG relationship under different market conditions. The study aims also to verify whether the impact of market conditions is decisive in this context. These aims determine the research concept; specifically, this study examines entrepreneurial behaviors during two periods that differ in terms of their market conditions, that is, during the recent pandemic crisis and after the crisis.

The sample represents small companies operating in the printing industry in Poland (150 of them were surveyed during the crisis, and 145 after the crisis). We used structural equitation modeling (PLS-SEM) to test mediation and moderation models and statistical tests to verify the significance of the observed differences. Specifically, this study tested separate models wherein FLEX acts as a moderator and mediator in the relationship between EO and FG. Each model was tested twice: under crisis conditions and under non-crisis market conditions.

This study intends to add value to the organizational strategy and entrepreneurship literature. By exploring the roles of FLEX and market conditions in the relationship between EO and performance, this study specifically seeks to provide evidence that can be useful in explaining the ambiguity regarding the impact of EO on performance. This examination also strives to contribute to the theory of dynamic capabilities (and partly to resource-based theory) by showing that mediation or moderation of FLEX could be diagnosed under various conditions of environmental dynamism and hostility. As previously mentioned, changing market conditions may affect the role of a given strategy when analyzed in the context of more complex relationships (such as mediation or moderation). Therefore, we tested the role of FLEX for data from two periods: pandemic and post-pandemic (which were characterized by significantly different market conditions).

The novelty of the study manifests in an unusual analysis that involved the verification of two-level moderation; that is, to what degree market conditions determine the role of the factor (in this case, FLEX) that determined (moderated or mediated) the cause-and-effect relationship (in this case, EO–FG). Such a verification can explain the ambiguity regarding the role of FLEX in the EO–FG context as well as the moderating impact of market conditions on the role of FLEX. By testing the research procedure of verifying double-level moderation, this study can contribute to the research methodology.

This study tested the role of FLEX as both a mediator and moderator. This approach is inspired by previous studies on EO (see, e.g., Kraus et al., 2023); some have attempted to include a variable as a mediator or the moderator of a cause-and-effect relationship in other contexts as well, such as service innovativeness (Liu, 2011), perceived managerial support (Swang, 2010), or stress (Yang et al., 2008). However, the methodological explanation of this solution was not explained, and the analysis was limited to examining the statistical significance of both effects. In the case of FLEX, testing both the mediating and moderating roles was justified. On one hand, the FLEX strategy in its essence contains such elements that may result from entrepreneurial behaviors and attitudes expressed by EO, which provides grounds for treating FLEX as a mediator. On the other hand, some of its aspects are independent of deliberate and planned entrepreneurial actions and are related to certain characteristics of managers or environmental conditions that prevail and may affect the EO–performance relationship; this authorizes treating FLEX as a moderator for this relationship. Thus, we tested two roles of FLEX (mediating and moderating) under two different market conditions (crisis and non-crisis).

The structure of the remaining sections of the paper is as follows. First, we review the relevant literature and develop hypotheses. Then, we introduce the methodology. Next, we present and discuss the results. We conclude by indicating the contributions and limitations of the study.

Theoretical backgroundEntrepreneurial orientationOne of the most common operationalizations of entrepreneurship at an organizational level is EO. According to Miller (1983), EO mainly manifests with risk-taking, proactiveness, and innovation; however, Lumpkin and Dess (1996) proposed adding competitive aggressiveness and autonomy to the dimensions of EO. The understanding of EO is wider than that of entrepreneurial behaviors—it also refers to decision-making, strategy, and management philosophy (Zighan et al., 2021). Numerous studies have employed the construct of EO to explore the relationship between firm entrepreneurship and performance. However, the results are ambiguous; some studies have shown a positive impact (e.g., Kraus et al., 2012; Kusa, 2023; Suder, 2023), whereas others have demonstrated the lack of such an impact (e.g., Renko et al., 2009). This relationship can be unilinear (e.g., Morić Milovanović, 2022). This unclear evidence can be explained by interference with other factors that may be relevant to both EO and firm performance; among these are diversification and interorganizational collaboration (Kusa, Duda, & Suder, 2022), social networks (Chin et al., 2016), network ties (Dwumah et al., 2024), strategic processes (Covin et al., 2006), organizational ambidexterity (Kafetzopoulos et al., 2023), digitalization (Suder et al., 2024), sustainability (Akomea et al., 2023), resource management (Adomako & Ahsan, 2022), knowledge sharing (Hormiga et al., 2017), adaptive capability (Eshima & Anderson, 2017; Salunke et al., 2013), or innovation performance (Ince et al., 2023). The relationship between EO and performance can be affected by external factors such as market conditions (e.g., Rosenbusch et al., 2013; Suder, 2024; Wójcik-Karpacz et al., 2018). These factors are considered to be antecedents, mediators, or moderators. Moreover, as EO is a multidimensional construct, the relationships among its dimensions can also be relevant, and its individual dimensions can impact performance in specific ways. For example, the impact of innovativeness and proactiveness on performance can be affected by the type and level, respectively, of risk-taking (Putniņš & Sauka, 2020), whereas risk-taking and innovativeness can positively affect proactiveness (Wach et al., 2023). Consequently, EO and its role in enhancing firm performance can still be examined.

Flexibility strategyThe growing importance of a dynamic approach in management emphasizes the need for an organization to constantly take opportunities and threats into account to constantly reconfigure plans and make strategic decisions (Arsawan et al., 2022). However, developing a strategy that will allow for flexible modifications in its organization and resources to adapt to changes in the environment is necessary (Baškarada & Koronios, 2018). Moreover, the adjustment itself should also occur in real time (Teece et al., 2016).

FLEX includes the ability to anticipate changes in the external environment; this can enable a firm to prepare for such changes (Brozovic, 2018) and take advantage of emerging opportunities in the marketplace (Grewal & Tansuhaj, 2001). Essentially, as stated by Ansoff (1965), FLEX is as an organizational characteristic that aids a business in adapting to environmental changes.

FLEX has been studied and analyzed in different contexts: the internationalization process (Rundh, 2011; Zhang et al., 2014), knowledge management (Pérez-Pérez et al., 2019), networking (Lemańska-Majdzik & Okręglicka, 2019), and family firms in self-employment (Molina, 2020).

Flexibility (FLEX) has been analyzed as strategic and operational. Operational FLEX is defined as “a company's ability to cope with or respond to environmental uncertainty as well as internal uncertainty” (Chahal et al., 2019, p. 157). Koste et al. (2004) and Nakane and Hall (1991) expressed the view that operational FLEX is a tool for improving a business’ performance and maintaining its competitive advantage in a changing environment. Strategic FLEX indicates “a company's ability to flexibly utilize and dynamically manage its resources in response to changes in the external environment” (Dayan et al., 2022). Yang and Yu (2022) showed that a company's strategic FLEX is its response to changes in the external environment that result from changing decisions regarding the uses and reallocations of resources. Strategic FLEX can be utilized as a strategic trait for dealing with an unpredictable environment and not give up on the defined company goals based on the premise that it is impossible to forecast all potential eventualities (Zhao & Yan, 2023). Furthermore, a flexible organization can readily adapt its strategy and structure, which enables it to successfully manage innovation and uncertainty (Saeed et al., 2021). According to Kafetzopoulos et al. (2023), an organization's strategic FLEX demonstrates its capacity to recognize noteworthy changes in its external environment. It also indicates that the organization can only operate when it can efficiently create and distribute its resources.

A strategy based on FLEX helps a business create and maintain a competitive edge; however, consideration should also be given to such perspectives as FLEX of planning, resources, and coordination (Umam & Sommanawat, 2019). According to Dibrell et al. (2014), planning FLEX (which comprises adaptable policies, plans, and strategies) enables businesses to seize unforeseen circumstances that unexpectedly arise in the business environment. With a focus on knowledge and information resources in particular, resource FLEX enables a business to move resources around in a reasonable and timely manner. Owing to this coordination's FLEX, resources can be allocated to plans for creating, promoting, and selling innovative products and services (Yousuf et al., 2021).

A trend in the literature (e.g., Sakib et al., 2022; Zaidi & Zaidi, 2021) has been to combine FLEX with a resource-based view (RBV) (Daradkeh, 2021) on the grounds that strategic FLEX helps a firm change and adapt its resources quickly, improve its resource-allocation efficiency, capture opportunities, and avoid risks. Moreover, dynamic capabilities theory has been used as an extension of the resource-based view, thus combining resource management and market dynamism. Dynamic capabilities, therefore, constitute the foundations that support the various dimensions of strategic FLEX (Singh et al., 2013). Strategic FLEX capabilities, such as one's absorptive capacity, ambidexterity, and continuous transformation (Widati, 2012), can be considered dynamic capabilities as they are associated with new resource configurations that are absolutely necessary for coping with intense change. Operational FLEX and EO have also been frequently linked to theories of the operational management (Vokurka & O'Leary-Kelly, 2000; Yu et al., 2015) and entrepreneurship (Rauch et al., 2009; Vega-Vazquez et al., 2016) fields.

Firm growthFG is a manifestation of firm performance (Wójcik-Karpacz, 2017). Through their growth, companies contribute to the economy's growth. For example, this is visible in SMEs, which have a positive impact on global economic growth (Jiang, 2023); consequently, their development and growth has been an important research topic for many authors (Dabić & Kraus, 2023; Singh, 2022). The growth and development of SMEs enhance their competitiveness and sustainability, as do the allocation and proper use of their resources (including technical [Muzamwese et al., 2024] and social resources [Pan et al., 2022]) if they are to outperform their competitors (Henriquez-Calvo & Díaz-Martínez, 2023).

Many factors influence the growth and development of SMEs. According to Denicolai et al. (2021), internationalization, digitalization, and sustainability are three key growth paths for companies. Espeche et al. (2023) found that internationalization through uprooting innovation led to firms’ growth and development under different market conditions, that is, during times of growth, recession, and recovery. In recent times, the digital revolution has had a major impact on the development of SMEs. On one hand, this has required implementing technological innovations such as artificial intelligence (AI) (Denicolai et al., 2021); on the other hand, it has facilitated the sensation of innovation and the development of SMEs as it offers opportunities for easy access to virtual global environments at relatively low costs (Ghobakhloo & Ching, 2019; Makarius et al., 2020). The application of sustainability principles influences company growth (ESPAS, 2019; Kolk & Pinkse, 2008; Muzamwese et al., 2024) and firm performance (Wang et al., 2023). Additionally, social capital is essential for a firm's development as it fosters information flow and knowledge-sharing (Casanueva et al., 2013; Pèrez-Luňo et al., 2011) and strengthens its identity and shared values (Meek et al., 2019; Stam et al., 2014). Business growth and development is also enhanced by network participation (UNIDO, 2011).

Printing industry in changing market environmentThe printing industry, encompassing packaging printing, publishing, advertising, and commercial printing, is an important part of the global economy. In 2017, its market value was $389 billion worldwide. This value was expected to increase to $421 billion by 2020 (PKO Bank Polski, 2018); however, in 2020, the market experienced a decline, bringing the value of printing back to levels recorded in 2016 owing to changing market conditions (Polskie Bractwo Kawalerów Gutenberga, 2022). Despite these global fluctuations, Poland has maintained its position as the largest printing market in Central and Eastern Europe and ranks fifth in the European Union in terms of revenue and employment. Polish printing companies generated €4.3 billion in turnover in 2020 alone. Additionally, in 2021, Poland became the leading global exporter of newspapers, dailies, and magazines, capturing 23% of global exports in these segments despite ongoing challenges, underscoring the sector's resilience and strategic importance in Poland (Polskie Bractwo Kawalerów Gutenberga, 2022).

In recent years, technological advancements and various crises have driven substantial changes in processes and operations, leading to profound transformations in many sectors, including the printing industry (Moreira et al., 2017). These changes have influenced business models and necessitated a shift towards more adaptive and innovative operational approaches (Zulkarnain et al., 2022).

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic had a tremendous impact on Poland's printing industry, bringing about unprecedented challenges and rapidly shifting market conditions. During the initial phase of the pandemic, printing companies experienced a sharp drop in demand as lockdowns and restrictions on business activities caused clients to reduce or suspend orders for printed materials (Cetera, 2021). Key sectors that typically relied heavily on print services, such as advertising, marketing, and events, also faced substantial operational restrictions, which further decreased the volume of orders (Cetera, 2022). Consequently, many companies in the printing industry reported deteriorations in their financial situations, which were marked by declines in overall economic performance, a reduction in export, and fewer entrepreneurs planning investments in the near future compared to the previous year (Polskie Bractwo Kawalerów Gutenberga, 2022).

The pandemic also disrupted global supply chains, which affected the availability of raw materials essential to the printing industry, including paper, ink, and other necessary resources (Poligrafika.pl, 2021). These disruptions led to delays and increased costs for raw materials (such as chemicals, for example, isopropanol, and ethanol), further straining company budgets. In addition to these cost increases, some companies encountered delays in payments from customers, which exacerbated their financial difficulties. The limited availability of external funding compounded the challenges, forcing companies to manage these issues with increased FLEX and find innovative solutions to survive. For many companies, this adaptability was a critical factor in their continued operation (Polskie Bractwo Kawalerów Gutenberga, 2022).

To address these challenges, many printing companies began introducing digital communication technologies and moving toward online modes of operation, establishing a “new normal” for business practices. This FLEX also extended to workforce management, with many companies restructuring teams and implementing remote-work arrangements where feasible. In response to changing market demands, firms began developing and implementing new products tailored to current needs, adopting a necessity-driven approach to innovation (Cetera, 2022). Government support programs, such as crisis-response funds, provided financial assistance, subsidies, and tax relief, which helped mitigate some of the economic impacts of the pandemic and enabled companies to maintain operations during this challenging period (Zulkarnain et al., 2022).

Following the pandemic, Poland's printing sector began to recover gradually. As economic growth resumed and restrictions were lifted, demand for printing services rebounded, especially from industries actively rebuilding their marketing and event activities (RynekPapierniczy.pl, 2023a). This period was characterized by relatively stable market conditions and effective supply chains, which facilitated a more consistent flow of essential materials. With these improvements, Polish printing companies managed to regain stability, and their share of the European market began to increase, which highlights the sector's resilience (Polskie Bractwo Kawalerów Gutenberga, 2022).

A noticeable trend toward sustainable development also emerged as companies adapted to post-pandemic realities. Printing firms increasingly invested in eco-friendly technologies and materials to meet customers’ evolving demands and comply with environmental protection regulations (RynekPapierniczy.pl, 2023b). As a result, companies began implementing new products and innovations that aligned with sustainable practices. The focus of innovation shifted from necessity-driven changes to a proactive approach fueled by a willingness to grow and develop in a competitive market.

The experience gained during the pandemic period reinforced the importance of adaptability and innovation for printing companies. Many firms continued to invest in digital technologies, such as digital printing, which provides greater production FLEX and enables short-run orders. These investments have allowed companies to respond more rapidly to customer needs and changing market conditions (Konica Minolta, 2023). The companies that successfully navigated the pandemic often revised their management approaches, introducing more agile organizational structures that facilitated swift adaptation to market shifts. Additionally, increased emphasis was placed on employee training and development to better equip staff for working in a dynamic environment.

The descriptions above illustrate that the operational conditions in Poland's printing industry varied significantly across the pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic periods. Prior to the pandemic, the industry benefitted from stability and predictability, supporting growth and development. During the pandemic, companies faced numerous operational constraints, supply chain disruptions, and decreased demand, compelling businesses to adapt to a highly uncertain and challenging environment. In the post-pandemic period, the market began to recover gradually, with the industry embracing new realities, including heightened demands for sustainable practices.

Hypothesis developmentEntrepreneurial orientation and firm growthAs stated above, EO affects firm performance (Adomako et al., 2016). This positive impact of EO also refers to the particular dimensions of performance, such as firm development (Chaston & Sadler-Smith, 2012; Hughes & Morgan, 2007) and FG (Covin et al., 2006; Gupta, 2019; Luiz dos Santos & Marinho, 2018). The impact of EO on growth has also been observed in SMEs (see, e.g., Ferreira et al., 2011; Sheppard, 2023). Moreno and Casillas (2008) posited that researchers tended to implicitly assume the positive relationship between EO and growth orientation. However, the impact of EO on sales growth is insignificant in the context of ethnic-minority-owned small businesses in the UK (Wang & Altinay, 2012). More-detailed studies have shown that the individual dimensions of EO can impact growth in different ways; in the SMEs context, risk-taking can positively affect growth, whereas such an effect is not observed in the case of innovativeness (Sorama & Joensuu-Salo, 2023). The impact of EO and its individual dimensions on FG can be indirect; for example, competitive advantage can mediate the impact of EO (Kiyabo & Isaga, 2020), whereas the impact of proactiveness can be mediated by digitalization (Suder et al., 2024). Interestingly, Eshima and Anderson (2017) observed that a firm's prior growth could lead to increased EO; in this transformation, the adaptive capacity plays the role of enabler in understanding market expectations. The above review encouraged us to propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis H1. Entrepreneurial orientation impacts firm growth.

Entrepreneurial orientation and flexibilityThe nature of organizational FLEX means that it is often associated with strategic orientation and corporate entrepreneurship. A study by Nassani et al. (2023) showed that strategic FLEX enhanced SMEs’ strategic orientation.

FLEX is positively related to EO (Su, 2022). Strategic FLEX is necessary for entrepreneurial ventures to take advantage of promising business opportunities that emerge in a turbulent market environment (Brinckmann et al., 2019). This explains the role of FLEX in the use and control of resources for entrepreneurial ventures for quickly entering any new niches created by a changing environment (Hensellek et al., 2023).

Particular attention has been paid to the importance of EO as a factor that enables strategic FLEX in SMEs (Nadkarni & Nakarayanan, 2007). Moreover, Herhausen et al. (2021) conducted a broad analysis of the antecedents, consequences, and contingencies of strategic FLEX. In this study, EO was treated as an enabler of FLEX, showing a positive relationship with it. In another paper, Arif (2019) showed a positive and statistically significant correlation between the dimensions of EO (innovation and risk-taking) and strategic FLEX in its surveyed companies. However, the full relationship between proactivity and the dimensions of strategic FLEX could not be confirmed. Chin et al. (2016) emphasized the mediating role of strategic FLEX in relation to SMEs from emerging and transition markets. Many studies have confirmed the positive impact of FLEX on the relationship between proactivity (one of the dimensions of EO) and the results achieved by SMEs in China, which were forced to conduct proactive behaviors to develop business networks, fill new niches, and achieve competitive advantages (Chin et al., 2016). Consequently, strategic FLEX enabled the constant recalibration of the firms’ strategies during environmental turbulence. The above considerations led to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis H2. Entrepreneurial orientation impacts flexibility.

Flexibility and firm growthFlexible organizations adapt to changing circumstances in competitive, technological, and social environments by making business changes and transferring resources among their business units. A flexible approach provides the opportunity to deploy resources in new contexts, acquire new skills, and profit from competitive weaknesses (Arunachalam et al., 2022).

Pinheiro et al. (2022) suggested that, although FLEX was an organization's ability to operate toward FG or greater efficiency than its competitors, several contextual factors made this relationship ambiguous. Most researchers have argued that strategic FLEX is beneficial to companies (Awais et al., 2023; Nadkarni & Herrmann, 2010). Brozović et al. (2023) confirmed a connection between strategic FLEX and FG in SMEs. Strategic FLEX is beneficial in the context of a company's dynamic capabilities because it focuses on the flexible use of its resources and the reconfiguration of its processes (Johnson et al., 2003).

Herhausen et al. (2021) found that the performance effect of strategic FLEX was stronger in terms of innovation or market outcomes rather than financial outcomes. Similarly, De la Gala-Velásquez et al. (2023) confirmed a positive and significant relationship between FLEX and tourism companies’ innovations.

Flexibility may also have a negative impact on the growth and results of an organization as implementing flexible solutions may bring additional costs that negatively affect its efficiency (which is a priority for most organizations) (Ebben & Johnson, 2005). Similarly, the pursuit of efficiency requires the implementation of internal procedures that do not support FLEX (Weigelt & Sarkar, 2009). This led us to propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis H3. Flexibility impacts firm growth.

Flexibility as mediator in relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm growthA mediating variable is intermediate in the causal relationship between independent and dependent variables, explaining how and why the two variables are related (MacKinnon, 2001). The mediating effect of FLEX has already been analyzed in the area of research on entrepreneurship. According to the research of Said and Ahmad (2023), strategic FLEX has a partially mediating effect on the relationship between corporate entrepreneurship and organizational success in the pharmaceutical sector.

In turn, Kurniawan et al. (2019) confirmed the full mediating effect of strategic FLEX in the context of the impact of EO on business performance in a study among 194 SMEs in the craft sector in Indonesia. Supriadi et al. (2020) confirmed the same effect in their study on 150 manufacturing firms in Indonesia, while Irfan and Kusumastuti (2023) found the same effect within their study on 119 SMEs in Indonesia.

Research that used data from the German Startup Monitor confirmed the simple mediation of strategic FLEX in the relationship between entrepreneurial leadership and entrepreneurial venture performance. What needs to be emphasized here is that entrepreneurial leadership does not directly affect performance but that the mediator of strategic FLEX has a positive impact on this relationship, making it statistically significant (Hensellek et al., 2023).

Moreover, an opposite approach has appeared in the literature in which EO mediates the relationship between strategic FLEX and small business performance, assuming that an entrepreneurial company benefits from investing in strategic FLEX because it constantly reconfigures its existing resources and possibilities (Chaudhary, 2019). Hence, the following hypothesis was formulated:

Hypothesis H4. Flexibility mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm growth.

Flexibility as moderator of relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm growthModeration occurs when the effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable varies depending on the level of a third variable (called a moderator variable) that interacts with the independent variable (Edwards & Lambert, 2007). The FLEX variable has often been used as a moderating variable in the literature. For example, strategic FLEX was diagnosed as a variable that moderated the relationship between EO and business performance in research from 2022 among 273 startups operating in the United Arab Emirates; this was assessed by the growth of sales, net profits, employment levels, and market shares. This research confirmed that the higher the strategic FLEX, the greater the positive effect of EO on startup performance (Daradkeh & Mansoor, 2023).

The moderating effect of FLEX was investigated in Li et al. (2011). An inverse U-shaped moderating effect of resource FLEX and a positive moderating effect of coordination FLEX were found on the impact of EO on the speed of strategic change in Chinese firms. The unfavorable impact of excessive resource FLEX was explained by the fact that it could lead to organizational inertia, which made enterprises react less strongly to environmental changes, try less to be proactive, and limit their pursuit of various strategic goals in a hostile environment.

A study conducted in 152 hospitals in the US (Chahal et al., 2019) helped us understand the performance of EO by establishing the role of FLEX as a moderator. It confirmed that FLEX moderated the relationship between EO and hospital performance—in other words, the impact of EO on the hospitals’ financial and non-financial results was greater in the cases of higher levels of FLEX. The authors concluded that, although higher levels of EO enhanced innovation and proactivity to maximize internal and external customer satisfaction, this also resulted in increased uncertainty and risk. This problem could have been reduced with FLEX. The above allowed for the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis H5. Flexibility moderates the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm growth.

Role of market conditionsAs stated above, FLEX can play a crucial role in the context of varying market conditions. However, market conditions can determine the role of FLEX. For example, the environmental context can influence the triggering of strategic FLEX; however, a multitude of factors make this relationship ambiguous (Brozovic, 2018). As they prepare for uncertain futures, flexible companies are characterized by both their diversity of strategic responses and their rapid transitions from one strategy to another (Nadkarni & Nakarayanan, 2007). Cingöz and Akdoğan (2013) recognized that, in a stable environment, traditional management concepts and tools are sufficient for business success. If the environment's dynamics and uncertainty are high, however, companies must demonstrate higher levels of FLEX to gain sustainable competitive advantages. In this line, Claussen et al. (2018) postulated that strategic FLEX would be beneficial in dynamic environments but not in stable environments. The study of Guo and Cao (2014) also demonstrated that the role of strategic FLEX was more effective in improving performance in hostile environments with intensive competition. Herhausen et al. (2021) reported the moderating effect of environmental dynamics on the relationship between strategic FLEX and performance. In turn, Alsaad et al. (2022) emphasized the strategic importance of FLEX in emerging economies where their external environments are characterized by high degrees of uncertainty. FLEX allows for the faster transformation of innovative ideas into new products and, therefore, intensifies the responses of firm resources to changes in the external environment. However, various antecedents and random events often overlap (Combe, 2012), which makes it difficult to recognize the importance of the environmental factor.

Moreover, previous studies have indicated that the external environment is relevant when considering organizational entrepreneurship (including EO and its impact on performance). For example, EO can be helpful in responding to unforeseen situations (Hernández-Perlines, 2016; Rauch et al., 2009). This can be connected with the crucial characteristics of entrepreneurial behaviors, namely, opportunity-seeking and -pursuit. (Morris, 1998). Since opportunities are rooted in the external environment, entrepreneurs have the ability to monitor it and adjust their actions to any identified changes. Previous studies on EO have provided evidence on the impact of market conditions on EO (Covin & Slevin, 1989; Dele-Ijagbulu et al., 2020; Miller & Friesen, 1982; Rosenbusch et al., 2013). Recently, the changes in EO that resulted in response to the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic have also been observed in the Polish context (Okręglicka et al., 2021;Suder et al., 2024; Suder, 2024). Market conditions can also affect the relationship between EO and performance (Becherer & Maurer, 1997; Davis, 2007; Onwe et al., 2020; Wójcik-Karpacz et al., 2018). Finally, Kusa et al. (2022) reported the impact of market conditions on the relationship between entrepreneurial behaviors (including opportunity-seeking, proactiveness, and innovativeness) and FG.

Based on the evidence that market conditions can affect the variables and relationships investigated in this study, we posit that market conditions can affect the impact of FLEX on the relationship between EO and FG; in particular, market conditions can determine the role of FLEX in this context (moderating and mediating). Consequently, we have proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis H6. The role of flexibility in the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and performance is moderated by market conditions.

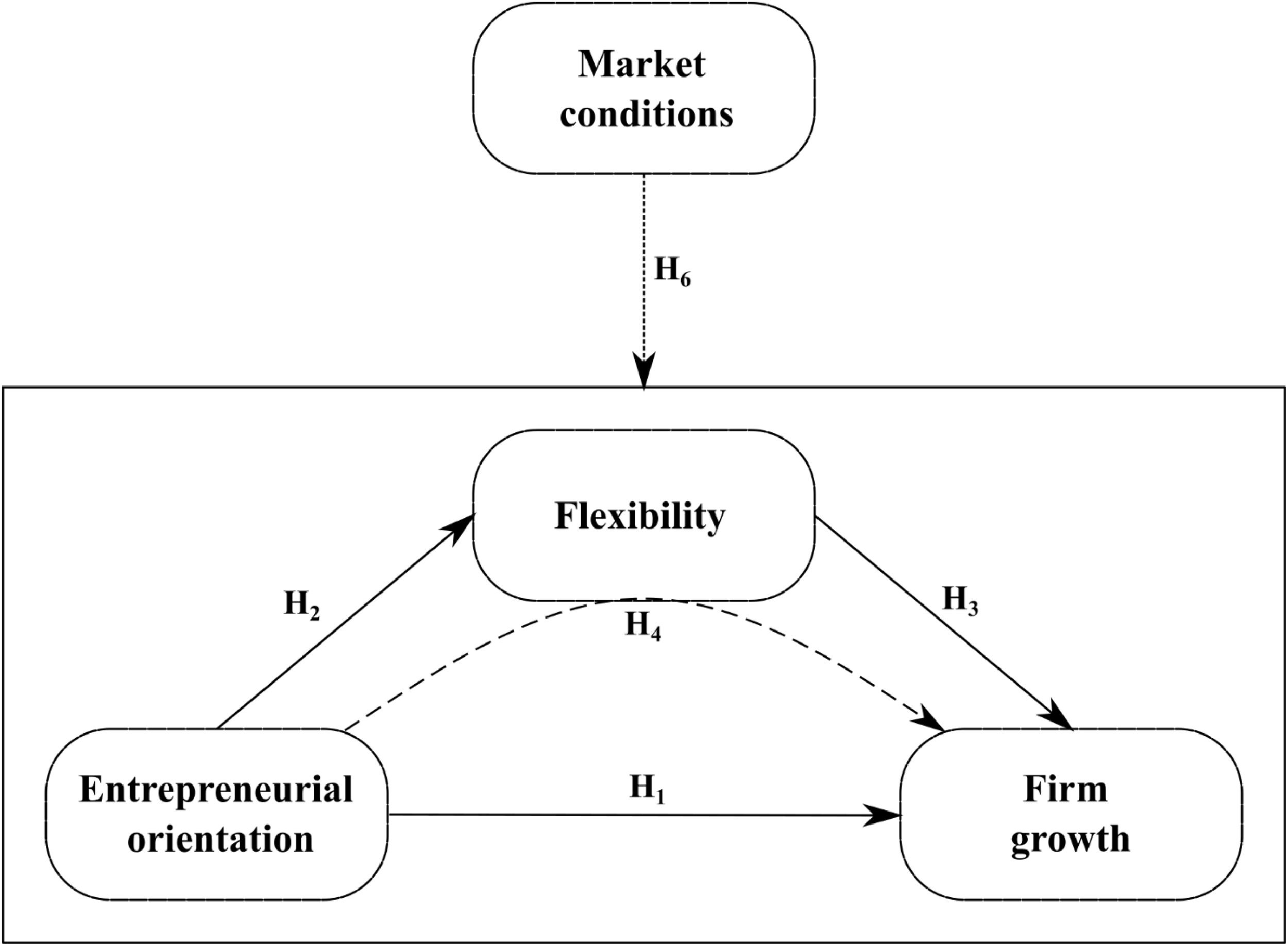

The relationships described above, as well as the proposed hypotheses, are presented in theoretical models depicted in Fig. 1 (mediating model) and Fig. 2 (moderating model).

The empirical research in this article is based on a quantitative approach that utilizes statistical analysis to understand, explain, and describe causal relationships by considering their mediating and moderating effects. We developed the research framework model and then empirically tested and analyzed it using a standardized questionnaire. The questionnaire underwent consultations with entrepreneurs and prominent scientists during its preparation. We used structural equation models to empirically verify the proposed hypotheses. The entire research process was conducted as was indicated by Aguinis et al. (2020).

Data collection and sampleWe selected the population for analysis deliberately, focusing on small businesses in the printing industry that had operated in Poland for at least three years. As previously mentioned, this industry was selected owing to its dynamic growth over the past decade, making Poland the largest printing market in Central-Eastern Europe and the fifth largest in the European Union (Polskie Bractwo Kawalerów Gutenberga, 2022). The sector faced challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, with disruptions in its supply chains leading to delays in paper and foil deliveries, which were primarily imported from Italy and China.

The study was conducted in two phases. The first phase took place from December 2020 through January 2021, involving a random sample of 150 small printing businesses that were drawn from the Statistics Poland and Dun & Bradstreet registers. We surveyed these businesses through a specialized research company using CAPI or PAPI methods, with the respondents being owners or top-level managers. During the second phase (conducted in April and May 2023, after the pandemic's resolution), approximately 540 businesses that met the criteria were identified in the same databases. We employed stratified-random sampling, which resulted in 150 completed questionnaires; finally, the data from 145 questionnaires were used in further analyses after verification. In the cases of both surveys (during Periods I and II), the sample error with an assumed 95% confidence level was 7%, which was an acceptable level. Table 1 presents the characteristics of the surveyed businesses from both periods.

Characteristics of surveyed groups.

| Characteristics | Category | Period I | Period II |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of employees | 10–19 | 51.0% | 54.5% |

| 20–29 | 16.0% | 13.1% | |

| 30–39 | 8.0% | 9.0% | |

| 40–49 | 25.0% | 23.4% | |

| Company age | 3–10 years | 14.0% | 9.0% |

| 11–20 years | 28.7% | 21.4% | |

| 20+ years | 57.3% | 69.6% | |

| Location | Rural areas | 8.7% | 7.5% |

| Towns* | 16.0% | 22.1% | |

| Medium-sized cities** | 42.0% | 34.5% | |

| Large cities*** | 33.3% | 35.9% |

Note: * up to 50,000 inhabitants; ** from 50,000 to 500,000 inhabitants; *** more than 500,000 inhabitants

A crucial aspect of the conducted research was the meticulous attention paid toward ensuring the anonymity and impartiality of the provided responses. The respondents were guaranteed confidentiality, and the scales utilized were designed to minimize the potential for social-desirability bias, demand characteristics, and ambiguity (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

Variables and methodsIn this study, FG is a dependent variable, while EO is an independent one; FLEX is tested as moderator and mediator. FG reflects a company's achieved development, including its increases in profitability, revenues, and market recognition as well as growth-orientation. EO is a second-order construct that comprises risk-taking (R), innovativeness (IN), and proactiveness (PR). FLEX represents an attitude toward a change and the willingness to implement it as well as its role in the development and improvement of a company's performance. All the variables are indices that consist of several items; these are presented in Appendix 1. Each item was assessed on a five-degree scale, with 1 = “fully disagree” and 5 = “fully agree.” The FG and EO constructs were adapted from previous entrepreneurship studies (namely, Hughes & Morgan, 2007; Kusa et al., 2021). Contrary to EO, various scales have been used to measure FLEX in previous studies (e.g., Daradkeh & Mansoor, 2023; Sen et al., 2023). Based on these, we proposed a new scale for this examination; a similar scale was used in the study on small hotels (Kusa et al., 2022). All the variables in this study were treated as latent variables.

The partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) methodology used in this study enabled us to analyze models with moderators and mediators (Chatterjee et al., 2023; Ferreira et al., 2024; Kusa et al., 2023; Suder & Okręglicka, 2023). From a statistical perspective, analyzing a single variable as both a moderator and mediator in the same relationship is only justified if the determinant in the model explains the variability (measured by the coefficient of determination R²) of the considered moderator to a moderate degree (at most). If the explanation's level was high or very high, treating the variable as a moderator would be unjustified. Therefore, this analysis first considered the mediation model (including the relationship between determinant [EO] and mediator [FLEX]). After confirming the feasibility of verifying the model with the moderator, we performed a moderation analysis.

Regardless of the tested model, the SEM methodology requires to verify any examined constructs as well as entire models. In this regard, the study followed the procedure outlined by Hair et al. (2022), which considered EO to be a second-order construct (as described by Sarstedt et al. [2019]).

Before verifying the constructs and models, we identified the presence of common method bias (CMB). To this end, we calculated the values of the variance inflation factor (VIF) or inner models to detect CMB (as recommended by Kock [2015]). In this study, all the VIF values were lower than 3.3, which indicated no collinearity problem and that the models were free of CMB (Kock, 2015).

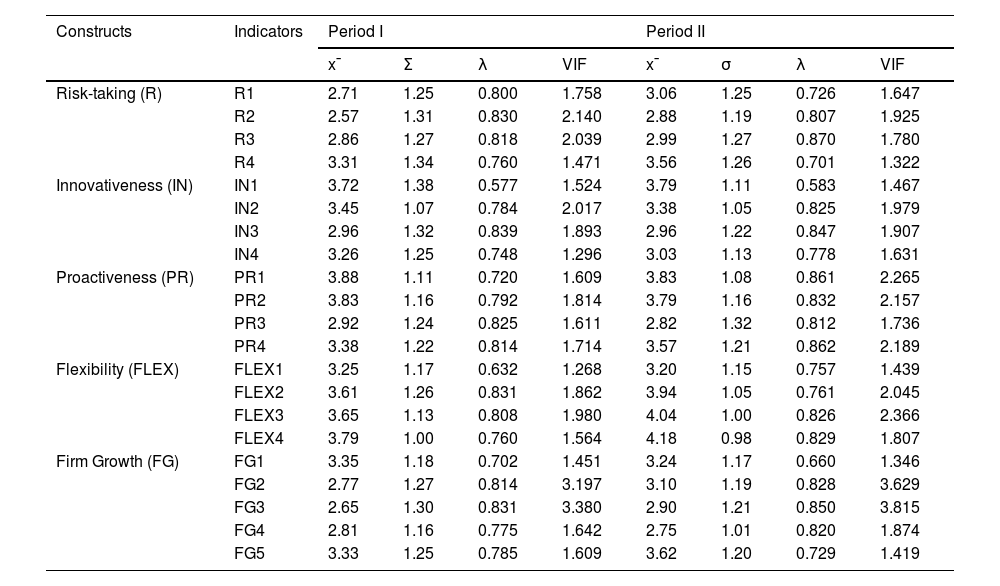

Most of the indicators exhibited outer loadings that significantly surpassed the 0.7 threshold, which is a widely accepted criterion that indicates high satisfaction with indicator reliability (Ali et al., 2018). In various instances, the values fell between 0.5 and 0.7—a range deemed acceptable given the substantial contribution of each indicator to the constructs (Hair et al., 2022). All the variance inflation factor (VIF) values were in proximity to 3 or below (see Table 2), which indicated a highly satisfactory outcome in this type of analysis and showed no problem of collinearity among the indicators that made up the construct (as stated by Diamantopoulos and Siguaw [2006]).

Measurement model evaluation results.

| Constructs | Indicators | Period I | Period II | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x¯ | Σ | λ | VIF | x¯ | σ | λ | VIF | ||

| Risk-taking (R) | R1 | 2.71 | 1.25 | 0.800 | 1.758 | 3.06 | 1.25 | 0.726 | 1.647 |

| R2 | 2.57 | 1.31 | 0.830 | 2.140 | 2.88 | 1.19 | 0.807 | 1.925 | |

| R3 | 2.86 | 1.27 | 0.818 | 2.039 | 2.99 | 1.27 | 0.870 | 1.780 | |

| R4 | 3.31 | 1.34 | 0.760 | 1.471 | 3.56 | 1.26 | 0.701 | 1.322 | |

| Innovativeness (IN) | IN1 | 3.72 | 1.38 | 0.577 | 1.524 | 3.79 | 1.11 | 0.583 | 1.467 |

| IN2 | 3.45 | 1.07 | 0.784 | 2.017 | 3.38 | 1.05 | 0.825 | 1.979 | |

| IN3 | 2.96 | 1.32 | 0.839 | 1.893 | 2.96 | 1.22 | 0.847 | 1.907 | |

| IN4 | 3.26 | 1.25 | 0.748 | 1.296 | 3.03 | 1.13 | 0.778 | 1.631 | |

| Proactiveness (PR) | PR1 | 3.88 | 1.11 | 0.720 | 1.609 | 3.83 | 1.08 | 0.861 | 2.265 |

| PR2 | 3.83 | 1.16 | 0.792 | 1.814 | 3.79 | 1.16 | 0.832 | 2.157 | |

| PR3 | 2.92 | 1.24 | 0.825 | 1.611 | 2.82 | 1.32 | 0.812 | 1.736 | |

| PR4 | 3.38 | 1.22 | 0.814 | 1.714 | 3.57 | 1.21 | 0.862 | 2.189 | |

| Flexibility (FLEX) | FLEX1 | 3.25 | 1.17 | 0.632 | 1.268 | 3.20 | 1.15 | 0.757 | 1.439 |

| FLEX2 | 3.61 | 1.26 | 0.831 | 1.862 | 3.94 | 1.05 | 0.761 | 2.045 | |

| FLEX3 | 3.65 | 1.13 | 0.808 | 1.980 | 4.04 | 1.00 | 0.826 | 2.366 | |

| FLEX4 | 3.79 | 1.00 | 0.760 | 1.564 | 4.18 | 0.98 | 0.829 | 1.807 | |

| Firm Growth (FG) | FG1 | 3.35 | 1.18 | 0.702 | 1.451 | 3.24 | 1.17 | 0.660 | 1.346 |

| FG2 | 2.77 | 1.27 | 0.814 | 3.197 | 3.10 | 1.19 | 0.828 | 3.629 | |

| FG3 | 2.65 | 1.30 | 0.831 | 3.380 | 2.90 | 1.21 | 0.850 | 3.815 | |

| FG4 | 2.81 | 1.16 | 0.775 | 1.642 | 2.75 | 1.01 | 0.820 | 1.874 | |

| FG5 | 3.33 | 1.25 | 0.785 | 1.609 | 3.62 | 1.20 | 0.729 | 1.419 | |

Note: x¯ – mean; σ – standard deviation; λ – loading; VIF – variance inflation factor

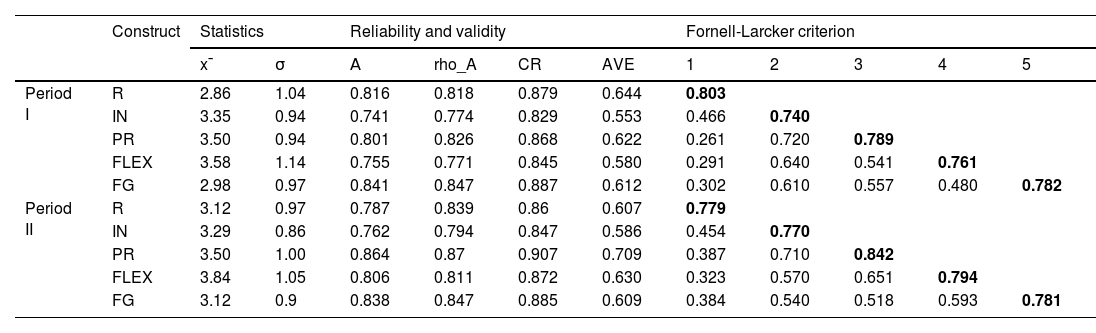

To evaluate the constructs’ reliability, measures such as Cronbach's alpha, a reliability coefficient, and composite reliability were utilized; the corresponding values are provided in Table 3. Kock and Lynn (2012) proposed a threshold of 0.7 for acceptability in these measures. According to Diamantopoulos et al. (2012), the issue of redundancy does not arise if all measures remain below 0.95. Following the criteria set by Dijkstra and Henseler (2015), the rho_A statistic is additionally expected to be greater than Cronbach's alpha but smaller than the values of composite reliability (CR). All the examined constructs met the aforementioned conditions. The average variance extracted (AVE) values in Table 3 were greater than 0.5, which supported the constructs’ convergent validity.

Assessment of constructs’ convergent and discriminant validity.

| Construct | Statistics | Reliability and validity | Fornell-Larcker criterion | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x¯ | σ | Α | rho_A | CR | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Period I | R | 2.86 | 1.04 | 0.816 | 0.818 | 0.879 | 0.644 | 0.803 | ||||

| IN | 3.35 | 0.94 | 0.741 | 0.774 | 0.829 | 0.553 | 0.466 | 0.740 | ||||

| PR | 3.50 | 0.94 | 0.801 | 0.826 | 0.868 | 0.622 | 0.261 | 0.720 | 0.789 | |||

| FLEX | 3.58 | 1.14 | 0.755 | 0.771 | 0.845 | 0.580 | 0.291 | 0.640 | 0.541 | 0.761 | ||

| FG | 2.98 | 0.97 | 0.841 | 0.847 | 0.887 | 0.612 | 0.302 | 0.610 | 0.557 | 0.480 | 0.782 | |

| Period II | R | 3.12 | 0.97 | 0.787 | 0.839 | 0.86 | 0.607 | 0.779 | ||||

| IN | 3.29 | 0.86 | 0.762 | 0.794 | 0.847 | 0.586 | 0.454 | 0.770 | ||||

| PR | 3.50 | 1.00 | 0.864 | 0.87 | 0.907 | 0.709 | 0.387 | 0.710 | 0.842 | |||

| FLEX | 3.84 | 1.05 | 0.806 | 0.811 | 0.872 | 0.630 | 0.323 | 0.570 | 0.651 | 0.794 | ||

| FG | 3.12 | 0.9 | 0.838 | 0.847 | 0.885 | 0.609 | 0.384 | 0.540 | 0.518 | 0.593 | 0.781 | |

Note:x¯ – mean; σ – standard deviation; α – Cronbach's alpha; rho_A – reliability coefficient; CR – composite reliability; AVE – average variance extracted; elements in bold on diagonals show square roots of AVE

A crucial step in validating the model involves evaluating the constructs’ discriminant (differential) validity (as outlined by Kock [2020]). The Fornell-Larcker criterion coefficient was employed for this evaluation. According to Fornell and Larcker (1981) and Kock (2015), discriminant validity is established when the square roots of AVE exceed the correlations of a particular construct with the other constructs. The findings of discriminant validity affirmed that all the scrutinized constructs exhibited differential validity (as depicted in Table 3).

As EO was a second-order construct that utilized the latent variables derived in the initial phase of the analysis, the accuracy of constructing the EO construct was assessed (Table 4). All the specified indicators and measurements aligned with the intended criteria.

Assessment of measurement model as well as second-order construct's convergent and discriminant validity.

| Indicators | Loading and collinearity | Reliability and validity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λ | VIF | Α | rho_A | CR | AVE | ||

| Period I | R | 0.593 | 1.295 | 0.735 | 0.834 | 0.849 | 0.659 |

| IN | 0.935 | 2.470 | |||||

| PR | 0.867 | 2.075 | |||||

| Period II | R | 0.661 | 1.273 | 0.763 | 0.819 | 0.863 | 0.681 |

| IN | 0.902 | 2.184 | |||||

| PR | 0.890 | 2.040 | |||||

Note: λ – loading; VIF – variance inflation factor; α – Cronbach's alpha; rho_A – reliability coefficient; CR – composite reliability; AVE – average variance extracted

As one of the indicative criteria for model fit, the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) was also computed to assess the adequacy of the model fit (following the guidelines that were outlined by Henseler et al. [2015]). A value below 0.10 is considered indicative of a good fit (or below 0.08 in a more conservative approach, as suggested by Hu and Bentler [1999]). In our models, the obtained SRMR values ranged between 0.8 and 1, signifying an acceptable level of fit for the considered models with the data.

Thus, the results of validating the measurement model indicated that the model was suitable for the analyzed data and could be used to verify the hypotheses.

ResultsThe verification of the stated hypotheses was conducted in two stages. In the first stage, we based our assessment on the results that pertained to the two models (mediation and moderation) obtained for the data from the two considered periods to validate Hypotheses H1–H5. Utilizing the structural models, we examined the hypotheses and assessed the significance of the path coefficients in each of the considered models. The validation of the significance of the path coefficients was facilitated by employing bootstrapping with 5,000 sub-samples. This validation process involved two distinct methods. Initially, the t statistics were established, and the test probability values were derived from them assuming a standard 5% significance level during hypothesis verification (Hair et al., 2022). Following the approach of Ramayah et al. (2018), we also subsequently calculated the confidence interval bias corrected. If this interval had included 0, this would have suggested that the determined factor for a specific path in the model lacked significance. All the hypotheses underwent two-tailed tests for verification. Hypothesis H6 was verified by assessing the significance of the differences in the path coefficient values for the different periods. The verification utilized the Welch-Satterthwait test (Sarstedt et al., 2011; Matthews, 2017).

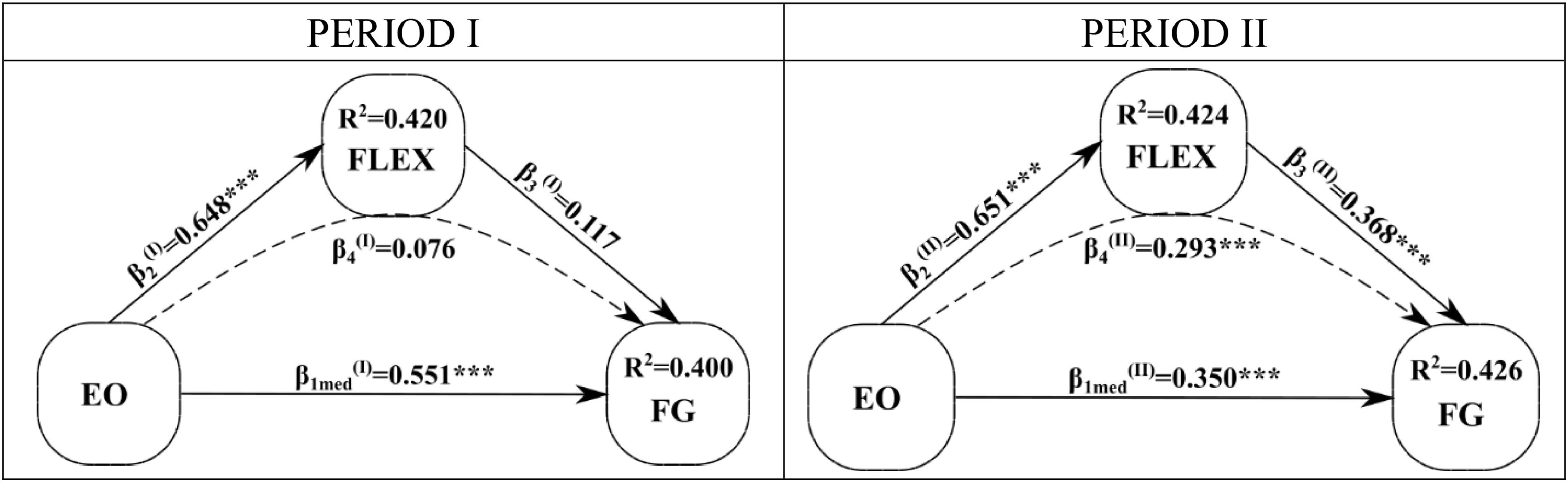

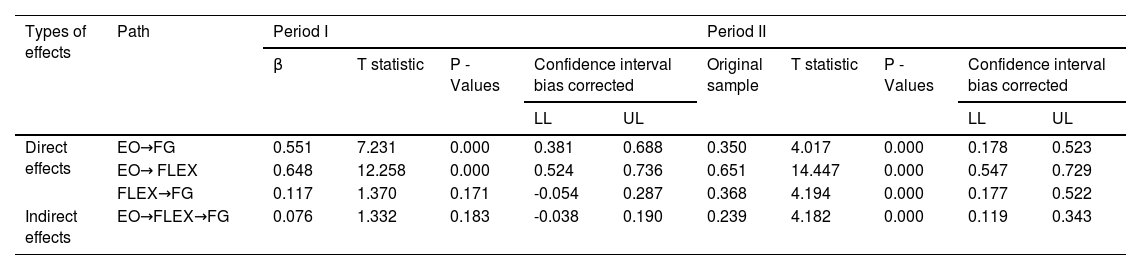

Flexibility as mediatorThe results that referred to the structural models that assumed the mediation of FLEX for both considered periods are shown in Fig. 3 and Table 5.

Hypothesis-verification results for models with mediation effect.

| Types of effects | Path | Period I | Period II | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | T statistic | P -Values | Confidence interval bias corrected | Original sample | T statistic | P -Values | Confidence interval bias corrected | ||||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | ||||||||

| Direct effects | EO→FG | 0.551 | 7.231 | 0.000 | 0.381 | 0.688 | 0.350 | 4.017 | 0.000 | 0.178 | 0.523 |

| EO→ FLEX | 0.648 | 12.258 | 0.000 | 0.524 | 0.736 | 0.651 | 14.447 | 0.000 | 0.547 | 0.729 | |

| FLEX→FG | 0.117 | 1.370 | 0.171 | -0.054 | 0.287 | 0.368 | 4.194 | 0.000 | 0.177 | 0.522 | |

| Indirect effects | EO→FLEX→FG | 0.076 | 1.332 | 0.183 | -0.038 | 0.190 | 0.239 | 4.182 | 0.000 | 0.119 | 0.343 |

The first hypothesis (H1) regarding the influence of EO on FG was confirmed for both periods I (β1med(I) = 0.551; p < 0.001) and II (β1med(II) = 0.350; p < 0.001). Owing to the positive signs of the path coefficients, we inferred that EO had a positive and significant impact on FG (both under turbulent and stable conditions). This result empirically confirmed the proposition that firms that were more oriented toward entrepreneurship had the potential for faster growth regardless of market conditions.

Similarly, the second hypothesis regarding the influence of EO on FLEX was confirmed in the sample of the examined companies. The path coefficients for the EO→FLEX relationships were β2(I) = 0.648 and β2(II) = 0.651, and the tests revealed that these values were statistically significant (the confidence interval bias corrected did not include 0, and the test probabilities were less than 0.05). These results affirmed that strong entrepreneurial behaviors (as expressed by EO) were the sources of high organizational FLEX in this study.

In the verification of Hypothesis 3, different results were obtained for the considered periods. The path coefficient that expressed the strength of the influence of FLEX on FG (with a value of β3(I)=0.117) for Period I proved to be statistically nonsignificant (p = 0.171 > 0.05, and interval [LL, UL] included 0). Conversely, the β3(II) = 0.368 result obtained from parameter estimation for the data from Period II proved to be statistically significant (p < 0.05). Even though our research indicated that FLEX positively affected FG during both periods, a significant positive impact could only be confirmed for Period II. This suggested that Hypothesis H3 was empirically confirmed for only the data from Period II (which represented stable conditions). This result provided grounds to conclude that, during stable times (e.g., Period II), FLEX, along with EO, leads to FG. Under unstable conditions (such as those influenced by the pandemic), however, the impact of FLEX is not significant.

The lack of a significant impact of FLEX on FG for the data from Period I implied that FLEX was not a mediator in the relationship between EO and FG. The indirect path coefficient determined for the EO→FLEX→FG relationship in the structural equation was β4(I) = 0.076 and was not statistically significant (p = 0.183 > 0.05); therefore, Hypothesis H4 was not confirmed for the data from Period I. Conversely, the study revealed the importance of the indirect path coefficient (β4(II) = 0.239; p <0.05); this indicated that the empirical analysis confirmed Hypothesis H4 for the data from Period II, and FLEX acted as a mediator between EO and FG (and since EO significantly influenced FG, the mediation had a partial character) (MacKinnon et al., 2007).

Additionally, the values of the coefficients of determination R2 were provided to assess the extent to which the exogenous variables explained the variability of the endogenous variables in Fig. 3. The obtained values of this indicator were close to 0.4 for both FLEX and FG regardless of the period. This value was significantly higher than the acceptability threshold proposed by Kock (2014) (which was 0.2).

To verify the results of the analysis regarding the mediating role of FLEX, the variance accounted for (VAF) indicator was used; this is defined by formula VAF=a×ba×b+c′·100%, where a×b is the path coefficient value for the indirect effect, and c′ is the direct effect (Hair et al., 2017). Helm et al. (2010) suggested that VAF values above 80% indicated full mediation, between 20 and 80% indicated partial mediation, and below 20% indicated no mediation effect. In the analysis performed for the data from both periods, the VAF values were VAF1=15.033%<20% and VAF2=42.613%∈[20%;80%], respectively. These results fully supported the conclusions of the earlier analysis indicating that FLEX was not a mediator during Period I while acting as a partial mediator in the relationship between EO and FG during Period II.

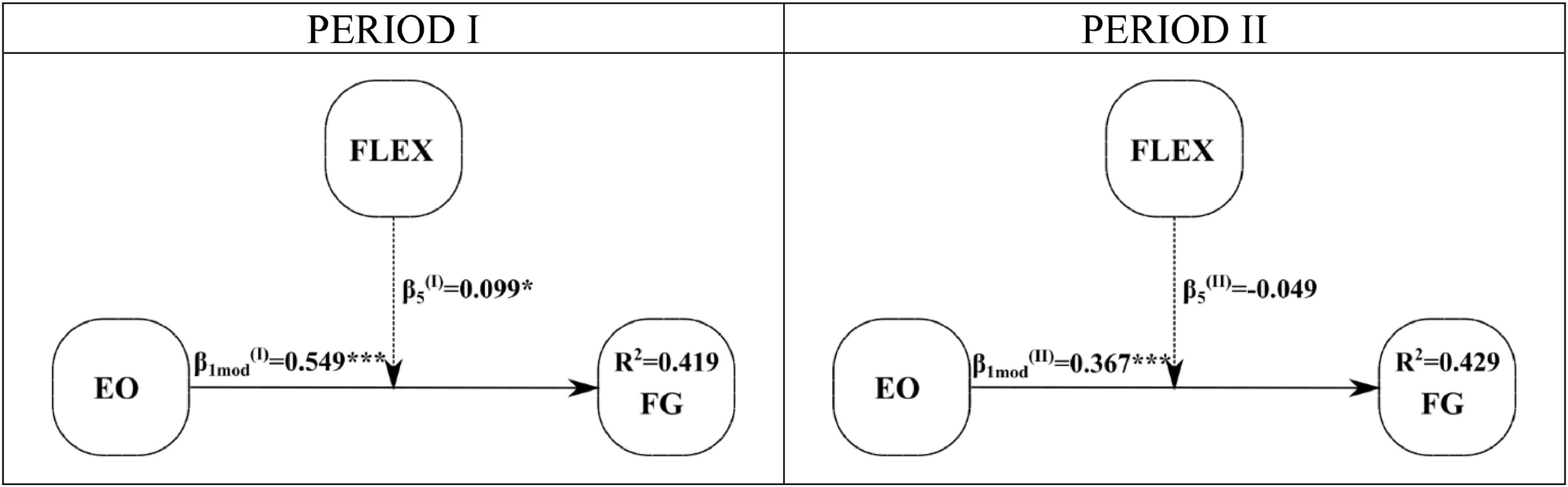

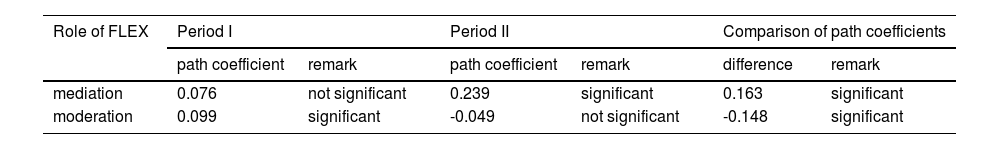

Flexibility as moderatorThe results of the analysis for the competitive model in which FLEX acted as a moderator for the EO→FG relationship are presented in Table 6 and Fig. 4.

Hypothesis verification results for models with moderation effect.

| Types of effects | Path | Period I | Period II | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | T statistic | P -Values | Confidence interval bias corrected | Original sample | T statistic | P -Values | Confidence interval bias corrected | ||||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | ||||||||

| Direct effects | EO→FG | 0.549 | 7.254 | 0.000 | 0.385 | 0.687 | 0.367 | 4.273 | 0.000 | 0.194 | 0.533 |

| FLEX→FG | 0.175 | 2.105 | 0.035 | 0.001 | 0.330 | 0.342 | 3.596 | 0.000 | 0.139 | 0.519 | |

| Moderation effects | EOxFLEX→FG | 0.099 | 2.090 | 0.037 | 0.011 | 0.197 | -0.049 | 0.731 | 0.465 | -0.187 | 0.076 |

The obtained path-coefficient values for the influence of EO on FG in the model where FLEX served as a moderator were nearly identical to those obtained for the models with FLEX as a mediator. Specifically, β1mod(I) (the path coefficient for the data from Period I) was equal to 0.549 and statistically significant (p < 0.000). Its counterpart for the data from Period II (β1mod(II) = 0.367) also proved to be statistically significant. These empirical results provided an additional confirmation of the fact that EO plays a crucial role in FG regardless of market conditions (thus confirming Hypothesis H1).

The results presented in Fig. 4 and Table 6 led to the conclusion that the moderating effect of FLEX was only significant for the data from Period I (which corresponded to a period of unstable market conditions). This implied that FLEX enhanced the impact of EO on FG for the examined companies by a significant value of β5(I) = 0.099. For the data from Period II, however, the path coefficient for the moderating effect proved to be negative (β5(II) = -0.049) and simultaneously not statistically significant (p = 0.465). Therefore, the empirical research confirmed Hypothesis H5 for Period I and did not confirm it for Period II. Thus, during periods of unfavorable and uncertain conditions, FLEX is a characteristic that significantly reinforces the positive effect of entrepreneurial activities on FG; conversely, this property is not noticeable during stable periods.

The values of the coefficient of determination R2 for the FG obtained for the models with the moderation effect (Fig. 4) were highly similar to those obtained for the models with mediation and were slightly above 0.4 (which we consider to be an average and fully acceptable value).

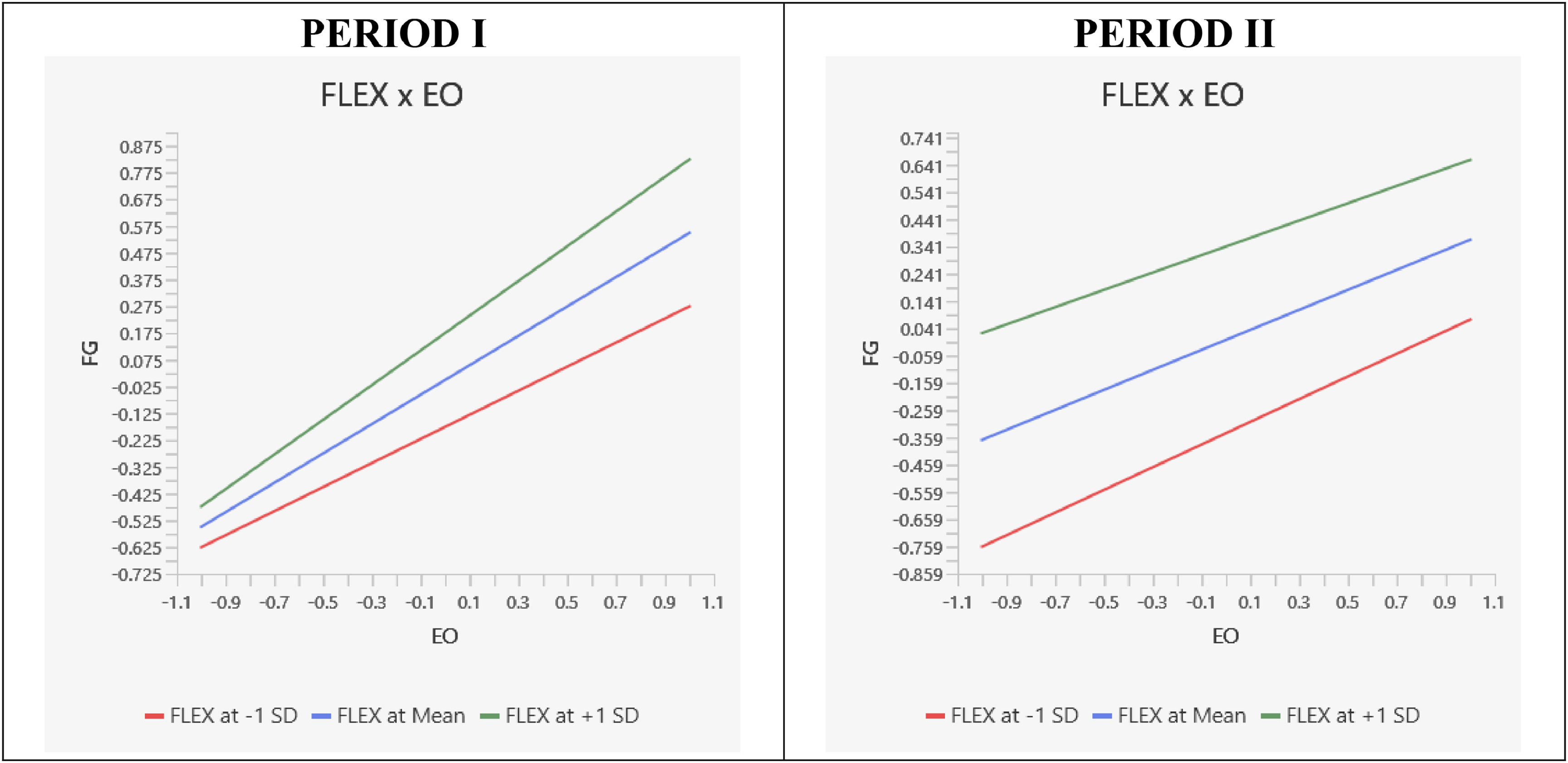

To further verify and illustrate the moderation effect, the results of the simple slope analysis are presented in Fig. 5. Specifically, a favorable moderating impact became apparent during Period I. The chart displays three lines that illustrate the connections between EO and FG. The central line signifies the relationship at an average level of the moderator variable (FLEX). Meanwhile, the other two lines depict the relationships between EO and FG for higher levels (i.e., the mean value of FLEX plus one standard deviation unit) and lower levels (i.e., the mean value of FLEX minus one standard deviation unit) of the moderator. The upper line (which represents a high level of the FLEX moderator construct) exhibits a steeper slope, while the lower line (which corresponds to a low level of the FLEX moderator construct) shows a flatter slope. This aligns with the positive interaction effect. Roughly estimating, the slope of the high level of the FLEX moderator construct is the simple effect (i.e., 0.549) plus the interaction effect (0.099); the slope of the low level of the FLEX moderator construct is the simple effect minus the interaction effect. Consequently, the simple slope plot reinforces our earlier discussion on the positive interaction term, that is, higher FLEX levels lead to a more robust relationship between EO and FG, whereas lower levels of FLEX result in a weaker connection between EO and FG. However, the moderation effect is inconspicuous in the slope plot for Period II as the lines on these charts are nearly parallel. This suggests the absence of the moderation effect and corroborates the previous discoveries.

Role of market conditionsThe conclusions drawn from the earlier analyses and verifications of Hypotheses 1–5 allow for a preliminary examination of Hypothesis H6. The influence of market conditions on the role that FLEX plays in the relationship between EO and FG is noticeable. As shown in Table 7 (which compiles the previous analysis results), market conditions determine whether FLEX acts as a moderator or mediator. During Period I, we only confirmed the moderating role of FLEX; during Period II, we only confirmed the mediating role. However, the fact that one path coefficient was significant while the other was not did not necessarily imply that the difference between them was statistically significant. To compare the strengths of the considered effects, we verified whether the path coefficients for the moderating effects and those for the mediating effects were significantly different. The results of the Welch-Satterthwait test (presented in Table 7) confirmed that the difference between the individual path coefficients was significantly different from 0. Thus, the strength of the considered effects (moderation or mediation) for the individual periods was significantly different. Specifically, the moderating effect was significant and significantly greater during Period I compared to Period II. Additionally, the mediating effect was significant and significantly greater during Period II compared to Period I. Therefore, we obtained empirical evidence that supports Hypothesis H6.

DiscussionThis study corresponds to several research areas, and it enters the ongoing discussion on the impact of EO on firm performance (see, e.g., Kraus et al., 2012; Putniņš & Sauka, 2020). In particular, our findings confirmed that EO positively impacts FG. This supports previous evidence on this impact; however, this relationship is not uniform in individual analyses, but its strength is determined by many variables. This has been confirmed by most researchers of this relationship; for example, Covin et al. (2006) confirmed the positive impact of EO on sales growth among manufacturing companies while, at the same time, diagnosing a greater sales growth based on EO in those companies that used autocratic decision-making and had the ability to shape an emergent strategy. Gupta (2019) also confirmed the positive relationship between EO and small firms’ growth; when he took the contextual factor of resource availability into account, however, the moderation proved to be different for the individual dimensions of EO (positive for innovativeness, neutral for proactiveness, and negative for risk-taking). In turn, Ferreira et al. (2011) pointed to the predictive value of EO for the growth of small firms. At the same time, they noted that entrepreneurial firms with greater growth potentials were those that had resources, developed more opportunities, and benefited from searching for these competencies. Similarly, Sheppard (2023) confirmed that a high level of entrepreneurial orientation was positively associated with high SMEs’ growth (which, however, was mediated by innovation performance variable). Our study adds value to this line of research by confirming the positive impact of EO regardless of market conditions, providing new insights into how this relationship evolves in different external environments. This does not mean that environmental conditions have not been analyzed in the EO–FG relationship; Sheppard (2023) made such an attempt to determine the moderating effect of environmental dynamics, but the study did not show that the paths were equal across those groups with both high and low levels of environmental dynamics. Additionally, Onwe et al. (2020) determined that a hostile environment motivated firms to adopt EO, ultimately improving their performance. This suggests examining not only the direct impact of EO on FG but also taking the influence of other organizational variables into account and considering market conditions.

Our study refers to FLEX, whose relationships with EO and FG were analyzed. The results regarding the associations between EO and FLEX are consistent with previous studies. For example, Su (2022) confirmed the positive impact of strategic FLEX on EO, with the combined impact of the governmental environment for entrepreneurship and the negative impact with the combined impact of the social environment for entrepreneurship. In particular, our findings supported the evidence regarding the influential role of EO on FLEX. Herhausen et al. (2021) summarized that EO was, among many elements, an enabler of FLEX based on several studies among a total sample size of 2,424 firms. In the SMEs sector, this was confirmed by Nadkarni and Nakarayanan (2007), who advocated that entrepreneurial intent may have been central to improving strategic adaption and FLEX. Our study shows that EO impacts FLEX under both stable and turbulent market conditions. This observation adds value to the previous studies on the impact of the environment on the EO→FLEX relationship (which provided inconclusive results). Chavez et al. (2017) presented the fact that turbulent environments encouraged a risky, proactive, and exploratory style that supports the ability of FLEX. Our study not only confirms the findings of the prior research, but it also extends the literature by analyzing both stable and hostile environments, thus providing a clearer picture of how EO and FLEX interact in different contexts. Hence, companies with high EO in dynamic environments often promote flexible capabilities, whereas FLEX may not be a competitive asset in relatively stable environments, and flexible solutions such as broader product lines may not provide benefits. Adomako et al. (2016) presented slightly different research conclusions that indicated that the EO–performance relationship was strengthened in dynamic environments, which created an urgent need for companies to acquire new knowledge and information in order to act flexibly by reconfiguring their resource bases. To ensure this, a boundary condition appeared in the form of extra-organizational advice. Our study shows that EO can be interpreted as an enabler of FLEX in companies regardless of market conditions.

FLEX contributes to companies’ efficiency and success (Awais et al., 2023; Nadkarni & Herrmann, 2010), including in the SMEs sector (e.g., Akbari & Beigi, 2023; Brozović et al., 2023). This mechanism can be explained, for example, on the basis of the dynamic capabilities theory, which points to the role of FLEX in the abilities of firms to renew, extend, and adapt their routines over time. Furthermore, some firms enter new ventures and business niches more quickly through the exploitation and control of resources and are, thus, more successful in both stable and dynamic environments (Herhausen et al., 2021).

Our findings regarding stable market conditions (Period II) were in line with previous research; however, our study also showed that FLEX did not affect FG in a turbulent market (Period I). This observation contributes to Pinheiro et al.’s (2022) position that several contextual factors make the impact of FLEX on FG ambiguous. In particular, our study shows that this impact can be affected by market conditions. However, the literature has mainly referred to the relationship between FLEX and business achievements under dynamic conditions (as in the study by Cingöz and Akdoğan [2013], who confirmed that strategic FLEX may improve a firm's innovation performance in a dynamic environment). Including both turbulent and stable conditions is a novel research solution. The inclusion of both stable and turbulent conditions in this study highlights the importance of investigating the dual role of FLEX in different market contexts, thus providing insights for further explorations of these mechanisms. Phillips et al. (2019) reached even more extreme conclusions, finding that the positive impact of FLEX on performance occurred only under dynamic market conditions.

Another achievement of our study was a general confirmation of the effect of FLEX on the EO→FG relationship. In this study, the FLEX variable was examined as both a moderator and a mediator. Both these roles have been analyzed in previous studies (albeit separately). On one hand, studies have indicated that strategic FLEX plays a positive moderating role in the relationships among EO, exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, and performance (Daradkeh & Mansoor, 2023) and startup performance (Akomea et al., 2022; Di Vaio et al., 2022). Chahal et al. (2019) showed that operational FLEX also played moderating roles in the relationship between EO and performance. In the sample examined in this study, FLEX moderated the EO→FG relationship under turbulent market conditions (Period I). The absence of the moderating impact of FLEX during Period II suggested that, under stable market conditions, FLEX was not crucial; instead, other factors could become more influential. On the other hand, the mediating effect of strategic FLEX on the relationship between EO and business performance has also been observed (e.g., Said & Ahmad, 2023), including for SMEs (Kurniawan et al., 2019). This evidence was supported by the findings of this study regarding stable market conditions; in this case (Period II), we found that FLEX plays a mediating role. In turn, the mediation of FLEX could not be observed in a turbulent environment (Period I). The absence of mediation in a turbulent environment can result from high market variability and uncertainty. This result differed from the study by Supriadi et al. (2020), who examined the impact of EO and a dynamic environment on performance simultaneously with the mediating influence of FLEX. They confirmed both indirect effects, finding that a dynamic environment could even create strategic FLEX in conducting all the business activities of a company. In a study of 119 respondents from creative-sector SMEs in Indonesia, Irfan and Kusumastuti (2023) similarly confirmed that strategic FLEX mediated the influence of EO and dynamic capabilities on an SME's financial performance. They concluded that this was especially true in a changing business environment. Strategic FLEX implemented in an organization can increase its awareness of potential environmental changes and compel it to effectively redirect needed resources to respond to the changes; this would allow it to face uncertainty and achieve better financial results. Implementing strategic FLEX in an organization can improve its operations and processes, reduce its costs, and increase its market growth and revenues (and, thus, improve its financial results).

The causes or determinants of the mediating or moderating effects of FLEX have yet to be resolved (which requires further analysis). The present research has focused on the role of the external environment in shaping the nature of this effect. As shown above, different roles of FLEX could be observed; thus, this study unveiled that the role of FLEX in the context of the relationship between EO and performance depends on market conditions. In particular, FLEX impacts FG and mediates the EO→FG relationship in a stable market, whereas FLEX does not impact FG nor mediate the EO→FG relationship in a hostile market. This evidence supports previous research showing that the role of FLEX in the entrepreneurial context varied depending on market conditions (see, e.g., Alsaad et al., 2022; Claussen et al., 2018; Guo & Cao, 2014; Herhausen et al., 2021).

In particular, the observation regarding the moderating role of market conditions adds value to the literature on the impact of the external environment on the relationship between EO and performance. In general, it confirms such an impact (as reported previously, for example, by Becherer & Maurer, 1997; Davis, 2007; Onwe et al., 2020; Wójcik-Karpacz et al., 2018). It also shows that the impact of market conditions can be indirect; in our case, market conditions moderated the role of FLEX, which in turn affected the EO→FG relationship. Thus, we observe a two-level impact. Specifically, in the case of the moderating role of FLEX, we find a two-level moderation effect: first, market conditions moderate FLEX; and second, FLEX moderates the EO→FG relationship (or not). In a similar way, market conditions moderate the mediating role of FLEX. As we investigated both relationships (moderating and mediating) under different market conditions in one study, we conclude that market conditions moderate the role of FLEX, namely whether it plays the role of moderator or mediator.

Theoretical implicationsThis study contributes to the existing knowledge and theory in the dynamic field of corporate entrepreneurship. It addresses a research gap regarding the role of FLEX in the relationship between EO and FG, specifically exploring whether FLEX serves as a mediator or moderator. Most prior studies have considered FLEX separately as either a mediator or a moderator, which may have led to unclear results. Our study provides a more integrated approach by exploring both mediation and moderation in the same context, thus allowing for a clearer understanding of how FLEX interacts with EO under different market conditions. This research expands previous evidence by examining how FLEX operates in different market environments, thereby deepening our understanding of this relationship.

Another key theoretical implication is how external factors such as market conditions influence the role of organizational FLEX. While previous studies in strategic management have emphasized the importance of adaptability, few have explored how FLEX interacts with EO in varying environments. This study shows that FLEX can act as both a mediator and a moderator depending on whether the market is stable or hostile. This offers a fresh perspective on how dynamic capabilities operate within firms—particularly regarding how firms can best leverage internal capabilities such as EO to navigate external pressures. This provides a nuanced understanding of how internal capabilities such as EO are associated with external pressures, thus highlighting the need to consider environmental conditions when analyzing the relationship between EO and FG.