This study is to understand the current status of online sustainability reporting (SR) practices by Irish universities. The paper reveals that online SR is in its infancy at the sample universities and there is significant room for improvement. Irish universities have initiated using web-based SR to inform their stakeholder groups, but they tend to report symbolic contents rather than substantive ones. The findings indicate that online SR practice by Irish universities is for the purpose of gaining legitimacy rather than satisfying the information needs of stakeholders. The assessment of online SR practices serves as a first step to help the universities use new technologies, in particular the internet, to improve the dialogue with stakeholders. This paper reminds universities that they should seek more than merely to meet the minimum acceptable level of online SR disclosure in society. The study will be of interest to university administrators, policymakers, regulators, and other stakeholder groups of universities.

Sustainability refers to the ability of a system to endure and maintain a desired state over the long term without harming the natural environment or depleting natural resources (Meadows et al., 2018). It encompasses social, economic, and environmental dimensions, and its ultimate goal is to achieve sustainable development, which the Brundtland Commission (1987, p. 6) defined as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” Sustainability reporting (SR) is the process of communicating an organization's sustainability performance to stakeholders (Kolk, 2016). SR provides information on an organization's social and environmental impact and its efforts to achieve sustainable development. The practice has become increasingly important in recent years as stakeholders are becoming more interested in the sustainability performance of organizations. The demand for SR has also been driven by regulatory requirements, investor expectations, and reputation management.

Universities, as important engines of growth and innovation in society, play a crucial role in ensuring the sustainable development of the global society and have a responsibility to use sustainable communication channels to report their social impacts (Marra, 2022; Richardson & Kachler, 2017; Sepasi et al., 2019). According to Richardson and Kachler (2017), universities “can model sustainable practices for society … by promoting sustainable practices in the campus environment” (p. 3). Sustainability practices and related initiatives that have become customary among universities include providing sustainability-related programs and courses, campus greening, and engaging in sustainability research (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015; Sánchez et al., 2015).

A number of universities across the globe have signed national, regional, and international declarations on sustainable development, including the Stockholm Declaration, Talloires Declaration, and Ubuntu Declaration (Lozano et al., 2013). Some university-specific assessment tools that focus on measuring sustainability performance have also emerged, such as the Auditing Instrument for Sustainability in Higher Education (AISHE) (Roorda, 2000), the Campus Sustainability Assessment Framework (CSAF) (Cole, 2003), the Graphical Assessment of Sustainability in Universities (GASU; Lozano, 2006), and the Sustainability Tracking, Assessment and Rating System (STARS; Richardson & Kachler, 2017). Apart from declarations and assessment tools for sustainability, universities are called to present to stakeholders and society their sustainable activities and performances through SR. SR helps universities to satisfy stakeholders’ information demands (Lozano, 2006), gain legitimacy (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2014, 2015), improve their public image (Sánchez et al., 2015), increase admission and talents (Alonso‐Almeida et al., 2014), to attract more funding (Alonso‐Almeida et al., 2014; Sassen & Azizi, 2018a; 2018b), and to increase university competitiveness (An et al., 2018). A standalone annual sustainability report is a common communication channel for a university to report its sustainability-related efforts and initiatives. However, with the development of information and communication technologies (ICT) and digital innovations, an alternative communication tool to the traditional standalone sustainability report—online SR adhering to the website—emerges. The use of the website helps in improving information transparency so that stakeholders can access information quickly and easily at a low cost (Meijer, 2009).

According to the extant literature, some universities have used websites to publish sustainability-related information and websites are increasingly a source for the public to learn about university sustainability (Amey et al., 2020; Filippo et al., 2020; Gamage & Sciulli, 2017). However, online SR on the university website has not been as well investigated as other ways universities have for revealing information, such as the standalone sustainability report. In other words, few studies have used the university website as a means for assessing sustainability-related disclosures to understand what and how universities are communicating about sustainability online (Gallego‐Álvarez et al., 2011). In this paper, we add to the previous literature by examining the online SR practices of Irish universities.

There are eight publicly financed universities in total in Ireland (Department of Education & Skills, 2020). According to the QS World University Rankings, all eight Irish universities were ranked within the top 800 in the 2020 World University Rankings, with Trinity College Dublin obtaining the highest ranking of 105. The sustainable development endeavors of some Irish universities have received worldwide recognition. For instance, the University College Cork (UCC) was the world's first university to be accredited by the ISO50001 standard certification for Energy Management Systems (Reidy et al., 2015); it was also awarded the status of the world's first “Green-Campus” by the Foundation for Environmental Education. UCC and the National University of Ireland Galway (NUIG) are also members of the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education, which developed the STARS assessment system. While there are no explicit legislative mandates requiring universities in Ireland to prepare sustainability reports, several initiatives have been undertaken to facilitate and encourage higher education institutions (HEIs) to incorporate sustainability into organizations. For instance, An Taisce (the Irish National Trust) launched the Green-Campus Programme in 2007, aiming to promote long-term sustainable campuses for HEIs (Green-Campus, 2016). In 2014, the Department of Education and Skills published a policy document (known as the “Education for Sustainability” National Strategy on Education for Sustainable Development in Ireland 2014–2020), to facilitate and promote sustainable development initiatives in HEIs. This policy aims to ensure HEIs include sustainability in their education and research and train students to contribute to the development of sustainability strategies, but does not enforce SR per se. The Higher Education Authority (HEA) Act 2021 aims to enhance governance, accountability, and performance in HEIs. It emphasizes the importance of sustainability, alongside equality, diversity, and inclusion, as part of the governance framework. While the Act does not explicitly mandate sustainability reporting, it does promote the integration of sustainability into the strategic goals and operations of HEIs. Additionally, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive, which Ireland is set to adopt, introduces broader SR requirements for large companies and public interest entities. Starting from 2025, entities with over 250 employees will need to comply with these standards. Although HEIs are not directly mentioned, those that meet the criteria will likely be subject to these reporting obligations. Therefore, while there is no specific legislative requirement solely for HEIs to produce sustainability reports, the general trend toward comprehensive SR in Ireland affects them indirectly, especially the larger institutions. HEIs are encouraged to align their practices with these evolving standards to ensure compliance and promote sustainability within their operations.

The focus of this study is the online SR practices of universities in Ireland, which are predominantly publicly financed. As key contributors to national education and research, these institutions play a vital role in promoting sustainable development within the community and the broader global context. This study aims to understand the current status, stakeholders’ perceptions, and underlying motivations, addressing two main questions: (1) How are Irish universities currently practicing online SR? (2) What are stakeholders’ perceptions of these practices and the motivations behind these practices? To answer these, we performed content analysis of the universities’ websites and conducted interviews with key stakeholders to gain insights into their understanding and perceptions of SR.

Our study makes four main contributions. First, this study aims to promote sustainable development in Irish society. According to Shawe et al. (2019), impediments to SR practices among Irish universities include the lack of appropriate policy response from the Irish Government and the lackluster approach of the Irish universities, which seek only to meet the minimum acceptable level proposed by the government. If Ireland is to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations, its universities need to model sustainable practices for society. Universities are expected to play a leading role in sustainable development and to provide guidance for practitioners in the area of SR practices (Adams, 2018). Providing an example of SR practices would lend more credence to universities’ operations and to the suggestions those universities make regarding the sustainability and corporate social responsibility practices of business practitioners. Thus, it is important to know to what extent Irish universities report information on sustainable development. To the best of our knowledge, there is a lack of research that investigates the online SR practices of Irish universities. This study provides evidence on how well HEIs in Ireland disclose sustainability online using the most recent information available on the internet. Second, from a methodological perspective, the university-specific SR framework constructed in this study is comprehensive and elaborative; it covers the most important elements of SR by comparing multiple relevant articles to prevent the omission of any important disclosures. The SR framework proposed by the current study would provide a more comprehensive set of guidelines for the implementation and evaluation of SR practices by Irish universities and could be applied to explore the SR of HEIs in other jurisdictions. Third, from a theoretical perspective, previous SR studies in HEIs infrequently provide theoretical explanations for SR practices. This study supplements the literature by focusing on stakeholder and legitimacy theories to explain the state of online SR practices by Irish universities. Fourth, from a practical perspective, this study confirms some limitations of SR practices that have been identified by previous, similar studies, while also complementing the literature by capturing some of the unique limitations of SR practices.

The remainder of the paper is structured in the following manner. Section 2 provides a review of the extant literature. Section 3 outlines the underlying theoretical framework. The research method is described in Section 4. Section 5 describes the results and discusses the research findings. Section 6 concludes the paper.

Literature reviewPrior studies have explored SR by universities in various jurisdictions, revealing significant variability and numerous challenges in achieving comprehensive and transparent reporting practices. Fonseca et al. (2011) examined the sustainability reports of seven Canadian universities and found that sustainability disclosure, with a primary focus on the environmental dimension, was not common. Similarly, Sassen and Azizi (2018b) noted that Canadian universities report a high level of environmental disclosures due to their involvement in the STARS program, while social disclosures remain low. This environmental emphasis raises concerns about the holistic understanding and communication of sustainability in HEIs. In the US, Sassen and Azizi (2018a) found that high levels of environmental disclosure are influenced by financial support for environmental projects from the US Government. However, Sánchez et al. (2013) pointed out that US universities’ SR often neglects the social dimension, which is critical for a balanced approach to sustainability. A preliminary analysis by Dade and Hassenzahl (2013) on US universities’ websites found that only 21 % addressed sustainability, indicating a lack of commitment to comprehensive SR. Australian universities, as examined by Sánchez et al. (2015), show a high level of environmental and socially responsible academic activity disclosures, particularly in energy management and recycling. However, there is an observed discrepancy in the emphasis on different sustainability dimensions, reflecting a fragmented approach to SR. This inconsistency underscores the need for a standardized reporting framework tailored to the higher education sector. Despite these efforts, SR in universities remains in its infancy with numerous shortcomings. Ceulemans et al. (2015) criticized the fragmented nature of SR, which hinders the public comparison of sustainability performance among universities. Furthermore, the lack of a generally accepted disclosure standard for universities exacerbates the issue, leading to variability in the quality and extent of disclosures (Sassen & Azizi, 2018a). This often results in misleading sustainability information (Fonseca et al., 2011), complicating efforts to assess true sustainability performance.

Recent studies by Nicolò et al. (2023), Andrades et al. (2024), and Moggi (2023) provide critical insights into the pressures and challenges faced by universities in SR. Nicolò et al. (2023) investigated the impact of universities’ board characteristics on online SR practices in Italian universities, finding that board gender diversity and the presence of female directors influenced SR practices. Andrades et al. (2024) highlighted how institutional pressures in the Spanish setting drive universities toward symbolic rather than substantive SR, aimed more at gaining legitimacy than addressing stakeholder needs. This aligns with Alonso-Almeida et al. (2015), who noted that universities often use SR to improve their public image and attract funding rather than genuinely enhancing sustainability practices. Moggi (2023) critiqued the applicability of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) standards to universities, arguing that these standards are not fully tailored to the specific needs and contexts of HEIs. This misalignment can lead to superficial compliance, with universities focusing on meeting minimum requirements rather than pursuing meaningful sustainability improvements. Consequently, universities may adopt a box-ticking approach to SR, undermining the potential for substantive stakeholder engagement and accountability. Hinson et al. (2015) found that Ghanaian universities do not release standalone sustainability reports, opting instead to disclose sustainability-related information through websites and annual reports. This practice, while increasing transparency, often leads to incomplete disclosures and fragmented information. An et al. (2017, 2018) similarly observed that universities in New Zealand and Hong Kong report high levels of environmental disclosures, yet economic and social disclosures are limited, reflecting a narrow focus that undermines comprehensive sustainability communication.

In conclusion, while there has been progress in adopting SR practices by universities globally, significant challenges and criticisms persist. While some studies highlighted the importance of external programs and governmental support in driving these disclosures, others pointed to the limited use of websites for comprehensive sustainability communication. Critically, these studies often overlooked the impact of legitimacy-seeking and stakeholder pressures on the quality and extent of SR. This study aims to build on these findings by examining the online SR practices of Irish universities, focusing on the extent and quality of disclosures and the motivations behind these practices.

Theoretical backgroundConceptual framework for online SRReporting sustainability-related disclosures online has become a common practice among universities around the world (Nicolò et al., 2023). It requires a systematic and comprehensive approach to ensure accurate and transparent reporting of sustainability performance. Thus, a plausible conceptual framework for online SR needs to be introduced to clarify the most effective ways of reporting.

Before reporting on sustainability performance, a university conducts a materiality assessment to identify the sustainability issues that are most relevant to its operation and stakeholders (Calabrese et al., 2016). The materiality assessment involves identifying the economic, social, and environmental impacts of the university, and the level of importance of these impacts to stakeholders. The university engages with stakeholders, including students, faculty, staff, and the community, to understand their sustainability expectations and needs, and incorporate them into the reporting process (Adams & Frost, 2006; Fonseca et al., 2011). This could include conducting surveys or focus groups to gather feedback on sustainability-related issues. After identifying the material sustainability issues, the university selects the indicators that will be used to measure and report on their sustainability performance. Indicators should be relevant, reliable, and comparable over time and across different universities. By following the conceptual framework for SR, universities can effectively report on their sustainability performance and meet stakeholder expectations. Reporting standards provide guidance on SR and help ensure consistency and comparability of indicators (Lozano, 2011). There are several generally used SR standards available, including the GRI Standards, the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board Standards, and the Integrated Reporting (IR) Framework. Universities can choose the reporting standard that best suits their SR needs. Some HEIs-specific sustainability assessment tools, such as STARS and the Higher Education Sustainability Initiative can also provide sustainability indicators that universities can use to report on their sustainability performance (Yáñez et al., 2019). SR from other universities or organizations can provide examples of best practices and benchmarks for SR. Government reports can provide indicators relating to sustainability performance and regulatory requirements as well.

The data collection from within the university includes the following steps. The first is to define the period for collecting data. The second is to identify sources of data. Online SR preparers determine which departments and units within the university are responsible for collecting data on the identified sustainability issues. For example, data on energy usage and greenhouse gas emissions may be collected by the facilities-management department, while data on waste management and recycling may be collected by the sustainability office. The third step is to work with the relevant departments and units to collect the required data. This may involve reviewing existing data and reports, conducting surveys or interviews, or installing monitoring equipment. The fourth step is to verify the accuracy and completeness of the collected data. This may involve comparing the data to sector standards, conducting data audits, or consulting with external experts. The fifth step is to analyze the collected data to identify trends, areas for improvement, and opportunities for sustainability performance. The sixth step is to update the data. It is important to ensure that the data are updated regularly to track progress toward sustainability goals and to ensure that the report remains accurate and relevant. Collecting data from within the university is a critical part of preparing sustainability-related disclosures. After collecting data, preparers determine the frequency of SR, such as annual or biennial reporting, and the level of disclosure. Then they make SR accessible to stakeholders by publishing it on the university's website. By following this conceptual framework for online SR, organizations can effectively report on their sustainability performance and meet stakeholder expectations.

Stakeholder theory and legitimacy theoryThis study adopts a theoretical framework, consisting of stakeholder theory and legitimacy theory, to explain the online SR practices by universities. Stakeholder theory asserts that organizations should be accountable to various stakeholders who have interests in the organization's operations and outcomes (Carpenter & Boyle, 2011). In the context of universities, stakeholders include students, faculty, staff, alumni, government bodies, local communities, and potential donors. Each of these groups has distinct expectations and needs regarding the university's performance and contributions to society. Universities operate in a multifaceted environment where they must address the concerns of these diverse stakeholder groups. For instance, students are particularly interested in the university's sustainability practices as they relate to campus life and their future employability. Faculty members focus on the support for sustainability research and teaching, while local communities are likely interested in the university's economic and social impacts on the local area. Applying stakeholder theory, universities can use SR to provide transparency about their efforts and achievements in sustainability. This transparency helps to build trust and maintain positive relationships with stakeholders. Effective SR should, therefore, include comprehensive information that addresses the specific interests and concerns of these stakeholder groups, demonstrating how the university's actions align with their expectations and contribute to broader societal goals (Aly et al., 2010; Debreceny et al., 2002; Deegan & Samkin, 2008; Gray et al., 1996).

Legitimacy theory suggests that organizations seek to operate within the bounds and norms of their respective societies (Del Sordo et al., 2016). For universities, this means acting in ways that are perceived as socially responsible and aligned with societal values. The theory posits a “social contract” between the university and the public, where the university must demonstrate its legitimacy by conforming to societal expectations and contributing positively to the community. Public universities, in particular, are scrutinized by society as they rely on public funding and resources [1]. To gain and maintain legitimacy, universities need to transparently report their sustainability activities and impacts. By providing detailed and accurate sustainability reports, universities can demonstrate their commitment to sustainable development and social responsibility, thereby reinforcing their legitimacy (Dowling & Pfeffer, 1975; Newson & Deegan, 2002; Sassen & Azizi, 2017). In practice, legitimacy theory implies that universities should not only perform sustainable activities but also effectively communicate these actions to the public. This involves not just fulfilling regulatory requirements but also showing leadership in sustainability. Comprehensive SR helps universities to meet public expectations and maintain their statuses as reputable institutions that contribute to societal well-being (Branco & Rodrigues, 2006; Herzig & Godemann, 2010).

Stakeholder theory and legitimacy theory are not mutually exclusive but rather complementary in the context of universities. Stakeholder theory focuses on meeting the needs and expectations of specific groups, while legitimacy theory emphasizes the broader social contract and societal expectations. Together, these theories provide a robust framework for understanding and enhancing SR practices in universities. By integrating both theories, universities can ensure that their sustainability reports are comprehensive and transparent, strategically aligned with the expectations of specific stakeholder groups and society at large. This dual approach helps universities to build stronger relationships with their stakeholders while simultaneously reinforcing their legitimacy and social license to operate. In the context of this study, stakeholder theory is used to examine the extent to which Irish universities use online sustainability information to communicate relevant details to their stakeholders. Legitimacy theory helps to explain the universities’ motivations for engaging in online SR, particularly how these reports help universities gain legitimacy by demonstrating their commitment to sustainability practices and societal contributions. These theoretical perspectives guide the analysis of online SR practices by Irish universities, providing insights into the motivations behind these practices and their implications for stakeholder engagement and societal legitimacy.

MethodologyThis section outlines the research design of our study, which includes both content analysis and an interview survey. The combination of these methods provides a comprehensive understanding of the online SR practices by Irish universities.

Research designThe research design of this study employs a mixed-methods approach, integrating both qualitative and quantitative techniques. This approach allows for a thorough examination of the online SR practices and provides richer insights by triangulating the findings from different data sources. The study is conducted in two main phases. The phase of content analysis involves a systematic examination of the sustainability-related information available on the websites of Irish universities, focusing on the actual online SR disclosures made by the universities. To complement the content analysis, we then conduct semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders from the universities, exploring stakeholders’ perceptions of online SR practices and the motivations behind these practices.

Sample selectionThere are eight publicly financed universities in Ireland, representing the main compositions of the Irish higher education sector. These institutions are crucial in understanding the broader landscape of sustainability practices within publicly funded educational environments. Among the eight universities, the oldest is Trinity College Dublin, founded in 1592, and the newest is Technological University Dublin, established in 2019. Our sample includes all eight publicly financed universities [2] (as indicated in Table 1) that are members of the Irish University Association [3].

Publicly funded universities in Ireland.

This study intends to examine the online SR practices by Irish universities. Content analysis refers to “a research method for the subjective interpretation of the content of text data through the systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes or patterns” (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005, p. 1278). Content analysis is a widely used technique in SR studies and different types of reporting, including standalone sustainability reports and online sustainability information, have been used in prior studies to examine the level of SR (Fonseca et al., 2011; Sassen & Azizi, 2018b; Yi et al., 2019). In this study, we apply content analysis to online sustainability information released by Irish universities. In line with Yi et al. (2019), the webpage, in web-browser format, is the only information source for content analysis, and other information sources, such as annual reports, are not considered [4]. Internal and external search engines (e.g., websites’ search functions and Google Search [5]) are used to search university websites for sustainability-related information (Hinson et al., 2015). The searches for this study were undertaken at the beginning of 2020.

This study's framework closely resembles that of Yi et al. (2019), which is based on the GRI SR guidelines and several prior influential studies (Fonseca et al., 2011; Lozano, 2011; Sánchez et al., 2015; Sassen & Azizi, 2018b). The current study categorizes the analyses of the status of online SR in Irish universities into two parts: the “form” area and the “content” area. The “form” area identifies some general characteristics of online SR according to the format. As in Yi et al. (2019), there are five items in the “form” area. First, we measure the disclosure level (frequency) of the “form” area. A binary scoring system is used, in which a score of 1 is assigned when an item is found on a university's website, and a score of 0 otherwise. Thus, the disclosure level of one specific item for all universities equals the ratio of the sum of the score of this item for each of the eight universities to the number of sample universities. The average disclosure level of the “form” area by Irish universities is equal to the mean value of the disclosure level of the five items from all eight universities. Second, we measure the disclosure level of the “content” area. The “content” area identifies the disclosures related to the “economic”, “environmental”, “social”, and “university” dimensions. The economic dimension includes disclosures that reflect the financial impacts of the university's activities. This dimension is important because it addresses the university's economic performance, contribution to the local economy, and indirect economic impacts. These aspects are crucial for understanding how universities manage their financial resources and contribute to economic development. The environmental dimension encompasses disclosures related to the university's impact on the natural environment. Universities have a significant role in promoting sustainability and mitigating environmental impacts through their operations and policies. The social dimension includes disclosures about the university's social responsibilities and its impacts on society. It reflects how universities contribute to social well-being and address social issues within and beyond their campuses. The university dimension is specifically tailored to capture the unique aspects of SR that are pertinent to HEIs. The inclusion of this dimension acknowledges the distinctive role that universities play in advancing sustainability through education, research, and community engagement. The four dimensions consist of 49 items. These 49 disclosure items were selected because they appeared at least three times in various literature sources. Multiple academic articles were compared to prevent the omission of important disclosure items and to ensure the comprehensiveness of the disclosure list. However, the list does not need to be too exhaustive, as including all possible disclosure items is unrealistic (Sun, 2021). As a result, 49 disclosure items identified in the key literature were selected. Of these, 43 items are derived from Yi et al.’s (2019) SR framework while six are sourced from research by Sassen and Azizi (2018a, 2018b), Sánchez et al. (2015), Hinson et al. (2015), Fonseca et al. (2011), and Lozano (2011). Thirteen disclosure items from Yi et al. (2019) were not selected, as they were not used in other scholars’ research, and their validity could not be confirmed. Details of the “content” area are exhibited in Appendix A. The “content” area is scored using both a dichotomous scoring scheme and a scoring scheme of “0–2” to arrive at the disclosure extent and disclosure quality of the “content” area. In terms of the disclosure extent of the “content” area, a score of 1 is awarded if an item appears on the website of the sample university, regardless of whether it appears qualitatively or quantitatively, and a score of 0 otherwise. Under this approach, the disclosure extent of the “content” area of a university is computed as the ratio of the sum of the actual score of 49 items to the maximum possible score (i.e. 49 items). In terms of the disclosure quality of the “content” area, we use a scoring scheme of “0–2” to identify “how an item is described” (Guthrie & Parker, 1990). A score of 0 is assigned when the item is not disclosed at all, and a score of 1 if the universities provide qualitative or quantitative disclosures. The highest score of 2 is assigned for a detailed description incorporating both qualitative and quantitative information simultaneously [6]. Under this approach, the disclosure quality of the “content” area of a university is computed as the ratio of the sum of the actual score of 49 items to the maximum possible score (i.e. 2 ☓ 49 = 98).

To ensure the consistency and accuracy of the data, two researchers participated in the coding process as coders. After coding training, which is considered necessary to avoid personal preferences or misunderstandings, two coders conducted a pilot test for online SR reporting by eight New Zealand public universities. Results attained were then compared using SPSS macro to calculate the Krippendorff's α coefficient for each comparison. The results—exhibiting that the Krippendorff's α coefficients were all above the threshold of 0.80—confirmed the reliability of the coding (Melloni, 2015). After the pilot test, one coder conducted the formal content analysis for online SR reporting by Irish universities independently to ensure reliability in the process of content analysis (Milne & Adler, 1999).

Interview surveyRoberts et al. (2021) underscore the effectiveness of a mixed-method design, integrating both content analysis and interviews, as a potent methodology that bolsters the dependability of research outcomes while also confirming their validity. As universities tend to satisfy the information needs of different stakeholders (Fonseca et al., 2011; Lukman & Glavic, 2007), this study conducted several semi-structured interviews with university administrators, teachers, scholars, alumni, and students to obtain a more in-depth understanding regarding the degree of online SR from the universities, which complements the content analysis. Eight participants, including two university administrators, two teachers, three scholars who specialize in the research area of CSR reporting and SR, one alumnus, and two students participated in the interview surveys. The size of the sample is small but suitable for this study. According to Patton (2002), the number of interviewees involved should depend on its appropriateness (e.g., usefulness, credibility, and considering time and resource constraints) but does not depend on any strict formula.

The interviewees represented a range of institutions, rather than a single university. This diversity helps to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the SR practices across different universities, rather than reflecting the practices of a single institution. Two open-ended questions were used to guide the interview process. The first was “What do you think about the online SR disclosure practices by Irish universities?” The second was “Why do you think Irish universities chose such online SR disclosure practices?” Because of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, all respondents chose a telephone interview. In total, eight interviews with a total of eight individuals were carried out on the phone. Each interview lasted around 20 min. Quotes from the interviews are provided in the following section.

Before the end of each interview, the participant was asked whether the online SR disclosure practice of Irish universities met his/her expectations concerning the sharing of information. All participants expressed that they were not satisfied with Irish universities’ online SR disclosure levels and that there was significant room for improvement. Then, participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement with the statement, “Irish universities’ online SR disclosure level meets your information expectation”. There were five options, namely: “strongly disagree” (1), “disagree” (2), “neutral” (3), “agree” (4), and “strongly agree” (5). All eight participants selected “strongly disagree” (1) and “disagree” (2).

Results and discussionAnalysis of the disclosure level of the “form” areaTable 2 shows the “form” area of the online SR of the eight universities. The disclosure level of the “form” area of online SR by Irish universities is 75 %. By contrast, the disclosure level of the “form” area of online SR by Italian public universities is 65 % (6.5/10), and for Hong Kong universities, it reaches 67.5 % (5.4/8) (Nicolò et al., 2021; Yi et al., 2019). Thus, the results of a comparative analysis suggest that in the “form” area of online SR, Irish universities perform soundly.

The “form” area of online sustainability reporting.

Some examples are provided to illustrate how different Irish universities are presenting their sustainability efforts online, providing a clearer understanding of the “form” area disclosures. Trinity College Dublin (TCU)’s website prominently features a dedicated section outlining its sustainability vision and strategy, emphasizing commitments to reducing carbon emissions, and promoting sustainable campus operations. This section includes detailed plans and targets for the upcoming years, illustrating the university's long-term sustainability goals. UCC has a comprehensive SR section on its website, where annual sustainability reports are accessible. These reports cover various aspects such as energy consumption, waste management, and community engagement initiatives, providing stakeholders with in-depth information about the university's sustainability efforts. Dublin City University (DCU) includes a site map that guides users to various sustainability-related pages, such as green-campus initiatives, sustainability research projects, and educational programs focused on environmental stewardship. NUIG publishes an annual standalone sustainability report that is available on its website. This report details the university's progress on sustainability goals, including specific metrics on waste reduction and energy efficiency improvements. The University of Limerick (UL) provides information about its dedicated sustainability committee, which is responsible for coordinating and implementing sustainability initiatives across the campus. The website details the roles and responsibilities of this committee, including ongoing projects and contact information for stakeholders interested in sustainability matters.

Analysis of the disclosure level of the “content” area (items and dimensions)The results of the content analysis of 49 items under four different dimensions are summarized in Table 3, indicating how the sustainability disclosures are reported.

The “content” area of online sustainability reporting.

The items of “economic performance” and “employment” are devoted particular attention by Irish universities given that the qualitative and quantitative information on the two items is reported by each sample university. Another interesting finding is that all the items disclosed using the quantitative form are also described using the qualitative form. Nineteen items, accounting for 39 % of the total number, are disclosed only in the qualitative form. However, 12 items (e.g. “security practices,” “anti-competitive behavior,” and “sustainability-related assessment”), accounting for 24.49 % of the total number of disclosures, are not reported by the sample universities at all. Among the 12 un-reported items, six fall under the “social” dimension. An interviewee (a teacher) provides an explanation for the reluctance to disclose such items by Irish universities: I don't mean social-level information such as anti-discrimination or anti-corruption is not important, they are just not what these rankings need … They are the basis of Irish society and are what the Irish are proud of … there is no need for universities to over-emphasize such information unless it is evident that universities have risks in these fields.

For qualitative disclosures, the “economic” dimension was the most widely reported among four dimensions. On average, 79.2 % of Irish universities reported this dimension in a qualitative way. By contrast, the “social dimension” was the least-reported dimension, as only 45 % of the sample universities chose to report this dimension in a qualitative way. As seen from the quantitative disclosures, the “economic” aspect was also the most widely reported (although only 50 % of universities disclosed this dimension). Only 8.8 % of universities chose to report the “social” dimension in a quantitative way.

Comparative analysis among Irish universitiesDisclosure extent is scored 1 if an item appears on the university's website, whether in qualitative or quantitative form, and 0 if it does not. It is calculated as the sum of scores for 49 items divided by 49. Disclosure extent reflects the breadth of how universities are reporting their sustainability practices. Disclosure quality is scored 0 if not disclosed, 1 if disclosed qualitatively or quantitatively, and 2 if both. It is calculated as the sum of scores for 49 items divided by 98. Disclosure quality reflects the depth of how universities are reporting their sustainability practices. We also conduct comparative analysis between Irish universities and universities in other regions. By comparing the online SR practices of Irish universities, we can identify which institutions are leading and which are lagging. This internal comparison helps in establishing benchmarks and best practices within the country, encouraging institutions to learn from each other and improve their SR practices. Comparing Irish universities with those in other regions provides a broader context, allowing us to evaluate how Irish universities perform on a global scale.

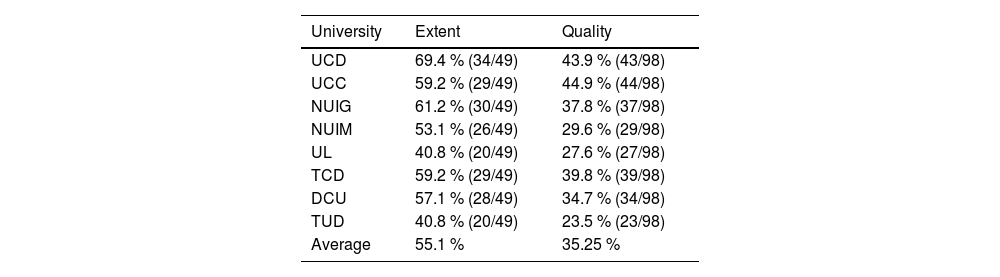

The average extent of online SR disclosures by Irish universities is 55.1 % (see Table 4). UCD has the highest extent of online SR disclosures (69.4 %), whereas Technological University Dublin (TUD) and UL have the lowest extent of online SR disclosures (40.8 %). By contrast, Fonseca et al. (2011) found that the Canadian university that reported 30 out of the 56 items had the highest extent of SR disclosures (54 %) and the average percentage of SR disclosures by Canadian universities was 37 %. Hinson et al. (2015) documented that the highest extent of SR disclosures among the six Ghanaian universities studied was 62.5 % (35/56), while the average percentage of SR disclosures was 57.2 %. Nicolò et al. (2021) observed that the extent of online SR disclosures by Italian public universities is high, reaching 59 % (29/49), and confirmed the “universities’ movement towards the digitalization of services and reporting practices by adopting innovative ways of collecting and communicating data such as websites” (p. 8).

The disclosure level of universities.

The average quality of online SR disclosures by Irish universities is 35.25 % (see Table 4). UCC has the highest quality of online SR disclosures (44.9 %) while TUD has the lowest quality of online SR disclosures (23.5 %). By contrast, Sassen and Azizi (2017) report that the average quality of SR disclosures in Canadian universities is 8.27 % (43/520) and the highest quality reaches only 18 % (92/520). Moreover, Sassen and Azizi (2018a) find that the average quality of SR disclosures in US universities is 7.87 % (40.91/520) and the highest disclosure quality is 53.27 % (277/520).

Theoretical implications: stakeholder and legitimacy theoriesStakeholder and legitimacy theories can provide some explanation for the state of online SR practices by Irish universities. Pursuant to stakeholder theory, universities operate in a sustainable manner and disclose a high level of sustainability-related information online to meet the expectations of a wide range of stakeholders (Hinson et al., 2015; Sassen & Azizi, 2018b). The results of the interview survey show that the use of web-based SR by Irish universities indeed provides some insights into university sustainability for stakeholder groups, such as students, teachers, the government, and the community. Using online SR can satisfy the information needs of students on the sustainability performance of a university. A student interviewee points out that: My university should communicate its sustainability performance with us students … we need to know if its operation threatens the society or environment … Yep, whether a university is sustainable decides our university selection … It is a very critical criterion for sure … When I applied to universities, I explored such information on university websites on purpose.

As stakeholders of a university, students are capable of influencing the university's access to necessary resources (Dong et al., 2014). One interviewee (a teacher) recognizes: We have been experiencing a funding crisis for several years due to the lack of students … We need to attract more students especially those from overseas … One of the most effective approaches is to show our contributions to sustainability development … University websites provide a perfect platform for conveying such information to overseas students.

In a similar vein, the government is another important stakeholder in a university. An interviewee (an administrator) believes that: Students especially post-graduate students are interested in information with regard to sustainability-related research … This kind of information is also of great interest to the government as it is one of the important factors that depends on whether they should fund the universities …

Teachers are also university stakeholders. An interviewee (a teacher) states: The university website is a good communication channel for teachers to understand the status quo of human resources … Teachers are a critical intellectual capital of the university … The human resources of the university significantly impact teaching and research activities … Informing the public that teachers are well treated is good for university new staff recruitment and the stability of the current teachers’ team.

Moreover, a university has an intense connection with the community. Informing stakeholders about how a university contributes to the community has become crucial to meeting stakeholders’ information demands (Nicolò et al., 2021). An interviewee (an administrator) explains that: We would like to present the image of a sustainability-oriented organization to our local community … We need the support of our community and the community also needs the contribution of the university …

Although the web-based SR is used to inform universities’ stakeholder groups, the disclosure levels show that Irish universities are not using this opportunity to adequately interact with stakeholders in the management of university sustainability. Based on the legitimacy theory, to survive in society, universities obtain legitimate status by reporting their activities, including their sustainability performance (Deegan, 2002; Sassen & Azizi, 2018b). There is evidence that the current online SR practice by Irish universities is largely for the purpose of gaining legitimacy. First, in Table 5, we observe that non-economic dimensions—such as the social dimension, with a total of 86 disclosures—are the most widely distributed. Non-economic dimensions are broader in scope, indicating that universities are pursuing legitimacy. Sánchez et al. (2013) argue that if a university is widely revealing non-economic aspects, this informs society at large about the university's activities and performances that fulfill social responsibilities, which helps the university to obtain or maintain its legitimacy. An interviewee (an administrator) admits: Universities are facing pressure from society requiring them to become involved in more social affairs. Meanwhile, the university has to give an active response to show it is making the commitment to perform its social responsibility.

Second, as reflected in Table 5, Irish universities mainly focus on the economic dimension. We can observe that both the extent and quality of all non-economic disclosures are lower than those of economic aspect. Sassen and Azizi (2017) believe that primarily focusing on the economic dimension verifies that universities do not genuinely use SR to improve stakeholder relations nor convey their willingness to dedicate themselves to being sustainable organizations. Moreover, a high distribution of the non-economic dimensions accompanying a low disclosure level reflects form over substance in the online SR practices by Irish universities.

Third, it should be noted that the disclosure level of the “form” area is higher than that of the “content” area, indicating that the current online SR reporting practice by Irish universities privileges form over substance as well. The reluctance of Irish universities to enhance the disclosure of sustainability-related information suggests more of a concern for legitimacy, than using online SR to satisfy the needs, expectations, and demands of stakeholders in terms of sustainability issues. An interviewee (a scholar) expresses a similar view: It is good to see sustainability information on the university's website … [Such information is] just emerging so [it is] often symbolic … People who care about university sustainability like me are quite interested in those disclosures … society puts pressure on them … Online SR is in its infant stage, universities just use it to make symbolic management.

Fig. 1 exhibits the analysis of data gained from the content analysis and interview survey; it consists of three dimensions: method, results, and findings. The method dimension involves content analysis—which systematically examines the distribution and level of sustainability disclosure—and interview surveys. From the distribution of SR disclosures, it can be observed that, overall, Irish universities report more non-economic than economic disclosures. However, although the quantity of non-economic disclosures is much greater than that of economic ones, the extent and quality of non-economic disclosures are lower than for economic ones. Moreover, the disclosure level of the “form” area is higher than that of the “content” area. As observed from the interviews, stakeholders perceive the online SR practices of Irish universities as inadequate to genuinely addressing their information needs. Derived from the three results of the content analysis, the findings indicate that Irish universities primarily focus on gaining legitimacy, as their online SR practices are symbolic (privileging form over substance). The findings derived from the interviews also suggest that Irish universities do not primarily focus on discharging accountability to stakeholders. In summary, compared with quests for legitimacy, stakeholder accountability plays a relatively minor role in Irish universities. In other words, the pursuit of legitimacy overshadows the aspirations of stakeholders for accountability.

Suggestions for online SRSome interviewees also propose several suggestions for the improvement of Irish universities’ online SR, particularly given that the world has changed irreversibly due to the COVID-19 pandemic. One interviewee (a teacher) admits: All our staff and students are facing the challenges caused by the COVID-19 pandemic … how to ensure their health and safety and exemplify our commitment? Online reporting provides a timely answer … You may see that every Irish university has a section about COVID-19 on its website to offer advice and support for staff and students …

Given the economic, social, and environmental challenges arising from COVID-19, SR by universities is transitioning to a new form that prioritizes reporting on how the university participates in overcoming the crisis brought on by COVID-19 (Biondi et al., 2020; Nicolò et al., 2021). IR, a new development in SR (Brusca et al., 2018; Montecalvo et al., 2018), is viewed as a key approach to help organizations cope with future risks caused by the COVID-19 pandemic (ACCA, 2020; Integrated Reporting Committee of South Africa [IRCSA], 2020). One interviewee (a scholar) believes that IR is able to offer a holistic picture of the organization by integrating financial and sustainability information, and can therefore be applied by universities when preparing online SR. According to Bommel (2014), IR “is a hybrid practice that spans between the different worlds of financial reporting and sustainability reporting” (p. 4), which supports the interviewee's opinion.

Given that not all sample universities provide sustainability reports, an interviewee (a scholar) points out: Although the websites of universities have offered abundant information regarding sustainability, the sustainability reports are still needed because online sustainability reporting of a university is dynamic, and a sustainability report is a summary of the dynamic information in one year.

This interviewee's view is consistent with the argument of Hassan et al. (2019). The researchers believe that the content of university websites regarding sustainability tends to be replaced at regular intervals, making it difficult to conduct a longitudinal analysis. However, permanent documents, such as sustainability reports, enable users to make a comparative analysis across years. Similarly, all the interviewees of Yi et al. (2019) admit that sustainability reports and online SR are equally critical. Additionally, another interviewee (an alumnus) finds that university information regarding sustainability is hard to identify. The alumnus states: As an alumnus, I am quite concerned with and interested in the sustainable development of our university … However, it is not easy for me to locate this kind of information because, you know, it is normally distributed fragmentedly on different webpages.

Similarly, Shawe et al. (2019) found that Irish universities’ information related to sustainability is not easy to access, because this kind of information is often not only unavailable, or non-existent, but is also incomplete, or dispersed across many webpages without links.

Firms have used their official websites as a medium for SR and accumulated experience in preparing online SR for many years (Adams & Frost, 2006). Some interviewees suggest that universities could learn from their corporate peers. Universities could identify the best practices by firms engaged in online SR and these best practices could serve as benchmarks. Moreover, universities could consider university–firm collaborations in sustainability-related knowledge sharing (e.g., online SR preparation). This kind of interaction between universities and firms would be productive (Marra, 2022) and effective online SR disclosure practices could subsequently be achieved.

ConclusionsThis study investigates the state of online SR practices by Irish universities. The paper reveals that although Irish universities have initiated web-based SR to inform their stakeholder groups, online SR is in its infancy at the sample universities. The content analysis and the interview surveys suggest that online SR by Irish universities occurs to promote the universities’ legitimacy rather than to satisfy the information needs of stakeholders. Specifically, content analysis reveals that Irish universities’ online SR practices are in their infancy, with a primary focus on legitimacy. The interview findings corroborate this by showing that stakeholders perceive these practices as symbolic efforts to gain legitimacy rather than genuine attempts to satisfy their information needs. Irish universities have not yet effectively used information technology to improve informational transparency and accountability. Pursuing legitimacy alone is not sufficient to effectively enhance the disclosure level of online SR, which largely depends on the pursuit of stakeholder accountability.

This study has several implications for academics, the government, and university administrators. First, owing to limited studies on online SR in universities, particularly in the Irish context, this study contributes to the extant literature. Second, the Irish Government should pay more attention to the sustainable development of Irish universities. Irish universities could play an important role in facilitating sustainable development in Ireland and eventually help Ireland to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations. Third, according to Sánchez et al. (2013, p. 735), “the internet, has provided means by which the expectations of different stakeholders can be identified and channeled, improving dialogue, and informational transparency and accountability”. Therefore, this study reminds Irish universities that they should seek more than to merely meet the minimum acceptable level of online SR disclosure and encourages them to seize the opportunity to use new technologies, in particular, the internet, to “involve and interact with stakeholders in the management of university SR questions” (Sánchez et al., 2013, p. 735).

The present study is subject to some limitations, which, however, may direct future research. First, as the institutional websites of universities are dynamic, the analysis only covers a single year to explore the current status of online SR disclosure by the sample universities. Many previous studies that explored online organizational disclosure likewise chose a one-year research period to analyze (Liu, 2014; Yi et al., 2019). Nevertheless, this short timeframe fails to capture the online SR disclosure trends over time. Future studies may consider conducting a longitudinal analysis of online SR disclosure over more than one year. Second, this study is confined to Irish universities, which may limit the applicability of its findings to other regions. Future research could be extended to universities globally to explore the overall state of online SR worldwide and make a comparison between countries, which may provide interesting findings on the differences in online SR disclosure practices between different institutions. Third, the representativeness of interviewees in our sample may be limited. As a result, our sample may not accurately reflect the entire population of administrators, teachers, scholars, alumni, and students at the universities studied. We acknowledge the limitations of our sampling approach and recommend that future research use probability sampling techniques, such as random or stratified sampling, to improve the representativeness of the sample. Last but not least, future studies with regard to the SR of HEIs could be carried out in the context of IR, which is a new development in SR (Brusca et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2022).

Notes[1] It is important to note that legitimacy theory is not limited to public universities. Private universities, though not financed by public funds, still rely on societal approval and support to attract students, faculty, and funding. Therefore, private universities also benefit from demonstrating their commitment to sustainability through transparent reporting, thereby maintaining their legitimacy.

[2] Our sample does not include the Munster Technological University, as it was established in January 2021.

[3] See https://www.iua.ie/ouruniversities/university-profiles/.

[4] We use website analysis here to assess online sustainability disclosure instead of a structured sustainability report.

[5] In cases where links concerning sustainability are unavailable, Google, Yahoo!, and Bing are adopted to locate the homepages of the universities (Hinson et al., 2015).

[6] Examples of qualitative and quantitative information:

- •

Sustainability-related Degree Programs and Courses: Qualitative Information: The university describes the existence of degree programs and courses focused on sustainability. For example, “We offer various degree programs and courses in environmental science, sustainable development, and renewable energy.” Quantitative Information: The university provides detailed data on these programs and courses, such as the number of programs, courses, student enrollment numbers, and graduation rates. For example, “We offer 5° programs and 12 courses focused on sustainability, with a total enrollment of 200 students annually.”

- •

Energy Consumption and Efficiency Measures: Qualitative Information: The university describes its energy consumption and measures taken to improve energy efficiency. For example, “We have implemented several energy-saving initiatives, including LED lighting and energy-efficient HVAC [heating, ventilation and air conditioning] systems.” Quantitative Information: The university provides specific data on energy consumption and savings. For example, “Our energy consumption for the year 2020 was 10,000 MWh, representing a 15 % reduction from the previous year due to our energy efficiency measures.”

- •

Community Engagement Activities: Qualitative Information: The university describes its community engagement activities related to sustainability. For example, “We conduct various community outreach programs to promote environmental awareness.” Quantitative Information: The university provides detailed metrics on these activities. For example, “In 2020, we conducted 20 community workshops on sustainability, attended by over 500 participants.”

- •

Emissions and Waste Management: Qualitative Information: The university describes its initiatives to manage emissions and waste. For example, “We have adopted a comprehensive waste management plan to reduce landfill waste.” Quantitative Information: The university provides data on emissions and waste. For example, “We reduced our carbon emissions by 10 % in 2020, and recycled 70 % of our total waste, diverting 500 tons from landfills.”

Yanqi Sun: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Dan Zhao: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Yuanyuan Cao: Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Cheng Xu: Validation, Data curation.