This study focusses on young entrepreneurs and considers the extent of business incubators’ impact on the development and visibility of projects headed by young people. To do so, we analyse incubators’ role as ecosystems for entrepreneurship in Spain based on the 2023 Funcas survey. First, we categorised incubators according to entrepreneurs’ age, defining young incubators as those in which most of the businesses are run by individuals under 35, excluding those over that age. We analyse variables that include the services offered and the frequency of events or training within the incubators to determine which approaches benefit or harm young entrepreneurs. This study uses a statistical approach, with quantitative data from the questionnaire as a starting point to characterise and identify young entrepreneurial profiles in business incubators. We develop and test two hypotheses using the chi-squared test, which is a non-parametric (distribution free) technique. Finally, we include a brief analysis of young entrepreneurs’ personality traits to shed light on some defining characteristics, concluding that personal initiative is a key feature amongst entrepreneurs under the age of 35. We conclude that the incubator system in Spain harms young entrepreneurs and propose some relevant recommendations to reverse this trend.

It is generally accepted that entrepreneurial activity promotes economic growth and development, offering an attractive instrument of innovation (Aghion, 2017; Galindo & Méndez-Picazo, 2013; Ribeiro-Soriano, 2017). To modernise rural areas, policy makers promote regional development through business incubators as mechanisms for nurturing and creating value for society (Lin-Lian et al., 2022a and b).

Fortunately, the trend of lack of studies concerning business incubators has reversed since the initial studies obtained limited and contradictory results (Albort-Morant & Ribeiro-Soriano, 2016). Recent research has demonstrated the role of incubators in developing business models for students during training (Freire-Rubio & Rosado-Cubero, 2015; Muslim Saraireh, 2021), how incubators facilitate entrepreneur networks (Busch & Barkema, 2022) and the increased number of people employed (Dlamini et al., 2022). Incubators’ influence on regional development has largely been found to be positive (Johannisson & Nilsson, 1989; Lawton Smith, 1996; Laukkanen, 2000; Benneworth, 2004; Muringani et al., 2021; Madaleno et al., 2022).

In addition to incubators’ influence on economic development, the support for entrepreneurial ecosystems is a novel way to promote supportive entrepreneurial environments. Entrepreneurial ecosystems have been investigated for understanding the context of entrepreneurship at the macro level of the organisational community (Stam & van de Ven, 2021). Some studies have demonstrated how a rich entrepreneurial ecosystem supports entrepreneurship and subsequent value creation at the regional level; for instance, developing a dynamic entrepreneurial ecosystem lifecycle model focused on the internal commercialisation of knowledge (Cantner et al., 2021). Another study defined the following taxonomy: first, the incubator managers develop confidence among local companies of association. Second, when companies ‘graduate’ (launch into the real work). Third, building trust in the incubator in which a region becomes extremely active in business and new start-up enterprises that require the incubator's services appear (Rosado-Cubero et al., 2023). Incubators that act as seeds of an entrepreneurial ecosystem can be useful for encouraging young people to start businesses.

An important aspect of the entrepreneurial process is related to governments’ role in the early stages of an ecosystem's development. It is inadequate to identify leading entrepreneurs to help them network, and traditional grants and subsidies may reduce the entrepreneurial core rather than encourage it, governments do not possess the right skillset or capabilities to advise or mentor entrepreneurs (Mason & Brown, 2014). However, strong skills and knowledge bases (i.e. apprenticeship schemes, entrepreneurship education and university research) are essential to ecosystem development, which requires collaborative industry–university efforts.

According to our findings, training workshops are a significant variable that favours entrepreneurship amongst young people, which resonates with previous studies that have explained that higher education levels and entrepreneurial experience are more likely to involve young people as members of teams in the entrepreneurial process (Pinzón et al., 2022). We argue that incubators benefit entrepreneurship when they offer training and connect entrepreneurs in different sectors.

This study examines the interdependent factors that enable and constrain the success of young entrepreneurs engaged in business incubators in Spain to determine the strengths and weaknesses of the current incubator system. Specifically, we aim to answer the following two research questions:

RQ1: Is a connection evident between the age of entrepreneurs in incubators and the amount of financial support received? If so, in what sense?

RQ2: Does the entrepreneur's age influence the extent to which they exhibit personal initiative? If so, in what sense?

We obtain a collection of statistical databases provided by managers of incubators to investigate the relationship between business incubators’ characteristics and contributions to advancing the success of young entrepreneurial talent. We expect some of the chosen variables to be statistically significant and others to be irrelevant for measuring the success.

This study contains two sections to examine the ways in which young entrepreneurs receive support from their affiliated incubators. We first analyse business incubator characteristics to determine their relevance, then focus on personal initiative (PI) as an entrepreneurial personality trait in the second section. Conclusions and discussion of results are included, and finally policy implications and recommendations complete the text. The preliminary conclusion is that incubators with a higher number of young entrepreneurs have lower budgets, tenants must pay more for services and incubators organise less frequent events, workshops and spaces or co-working opportunities.

Literature review and hypotheses developmentLiterature reviewScholars involved in the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) documented various forms of entrepreneurial activity across countries and regions over the years (Bosma et al., 2021), concluding that younger people are more likely than older people to start new businesses and younger adults tend to have less knowledge and experience, smaller networks, fewer resources and fewer skills. The first technology start-up accelerator, Y Combinator Management LLC, was founded in the United States in 2005. The incubator developed the tool that is widely used to evaluate start-ups and analyse the potential of specific business opportunities that is also called Y Combinator. While this application does not discriminate between young entrepreneurs and adults over 35 years of age, Y Combinator invests more in technology businesses where young entrepreneurs have more interest.

Notably, younger adults may have more energy, enthusiasm and tend to give up less in terms of an established career and high salary because they may not yet have to support a family, pay a mortgage and other lifestyle choices (Calvo et al., 2023).

Establishing business incubators in less developed countries can be a viable option for improving economic development. For example, business incubators in Oman provide shared resources and facilities for young businesses such as office space, consultants and personnel, with moderate yet promising success (Sanyal and (Sultanate of Oman), 2018). More recently, previous studies have defined the variables that can improve young people's entrepreneurship such as entrepreneurial education and self-perceived creativity to shape young individuals’ attitudes towards e-entrepreneurship (Abdelfattah et al., 2023).

In Mexico, when students complete a master's degree they generally do not consider pursuing entrepreneurial endeavours because of their age (Pérez Paredes et al., 2022). Previous studies have found that young people in Indian communities independently establish enterprises (Agarwal et al., 2020; Biney, 2023). Entrepreneurial intentions of young people in Indonesia are determined by the need for achievement, risk perception and locus of control (Wardana et al., 2020). Young people in Pakistan are eco-friendly and enjoy pursuits that can change consumer practices, with favourable market conditions for sustainable entrepreneurship (Soomro et al., 2020). In Malaysia, the key traits amongst entrepreneurs are individuals’ openness to experience and resilience (Sahrah et al., 2023). In Portugal, the importance of enhancing entrepreneurial culture and education to promote self-efficacy and develop entrepreneurial intentions has been recommended (António Porfírio et al., 2023).

Across Europe, young adults (18–34 years of age) are more likely than older adults (35–64 years of age) to start or run a new business, according to three of the classical GEM adult population survey questions addressed to young, emerging or established entrepreneurs only (but not non-entrepreneurs) (Bosma et al., 2021). The results indicate that western Europe has the highest levels of adults perceiving good opportunities to start a business locally who are deterred from doing so by fear of failure, which is especially high in parts of Spain, Portugal, France and the United Kingdom (Bosma et al., 2021). In contrast, in northern European countries such as Denmark, young founders who became ‘serial entrepreneurs’ have seen sales revenue nearly double between their first and second firms (Shaw & Sørensen, 2022).

In Spain, the years of COVID-19 pandemic restrictions affected young people tremendously and full socioeconomic recovery had not yet occurred in 2022; therefore, Spain has an ageing entrepreneurial profile (Calvo et al., 2023), and there are significant differences in motivation between juniors and seniors that can boost intergenerational cooperation (Perez‐Encinas et al., 2021). In Spain, a positive attitude towards entrepreneurship prevails amongst young people, who focus on working independently as alternative to unemployment, underemployment or increasing income sources (Adalid Ruiz & Kayahan, 2021). One study also determined that highly qualified young people tend to stay in Madrid, citing quality of life as the main reason (Angoitia, 2023). Another study demonstrated that entrepreneurs in northern Spain tend to maintain their businesses longer than those in the central zone (Yurrebaso et al., 2021). Previous research has shown that young tenants find incubators’ services most useful (Albort-Morant & Oghazi, 2016). This is a relevant point as well as other factors such as education level, professional experience and family experience.

This study focusses on young entrepreneurs that have been accepted into Spanish incubators to identify the characteristics of incubators that promote or hinder young entrepreneurs’ pursuits.

Hypotheses developmentThis study explores two hypotheses.

Based on previous research, particularly studies that have demonstrated that young incubator tenants find incubators’ services most useful (Albort-Morant & Oghazi, 2016) and to enhance the role of incubators in supporting young entrepreneurs, we propose our first hypothesis.

H1 There is a connection between the age of entrepreneurs in incubators and the amount of financial support received by incubators.

Sub-hypothesis The higher the average age of the entrepreneurs in an incubator is, the greater the financial support for the incubator will be.

A seminal article that remains relevant is the basis of our second hypothesis and reiterates the importance of PI in entrepreneurship. PI sharpens entrepreneurship, alongside other traits such as innovation and work performance (Frese & Fay, 2001).

H2 Entrepreneurs’ age influences the extent to which they exhibit personal initiative.

Sub-hypothesis Younger entrepreneurs will exhibit more personal initiative.

We employ a non-parametric statistical (chi-squared) test to evaluate the validity of our hypotheses and determine the significance of the different variables considered in incubators with young entrepreneurs.

MethodologyThe questionnaire was designed following earlier surveys designed for Ranking Global Funcas de Viveros de Empresas, which is calculated with data gathered since 2018. We group the items collected in the survey following the response criteria of the business incubators. These data correspond to surveys conducted in November and December 2023. We obtained a list of all existing incubators in Spain (413), contacting the person in charge (director or equivalent) of each incubator via email (questionnaire sent) and phone. The contact presented themselves as a member of the Funcas team, working towards the elaboration of incubators’ and accelerators’ Funcas ranking. If a response was not received within a reasonable period (approximately two weeks), they were contacted again, via phone and email, up to two more times. It took incubator managers about 30 min to complete the questionnaire. The final sample includes 93 questionnaires from Spanish incubators, representing 22.28 % of the total population of incubators, which is a reasonable response rate. The questionnaire included all items found in (Blanco Jiménez et al., 2021).

We gathered information about the different services that incubators offer, grouped into categories such as assistance and services, consultancy, project monitoring and seminars and workshops. Public and private financing is also relevant.

Frequently incubators offer parking spaces and support with consultancy services and project follow-up, as well as workshops to meet tenant companies’ demands. Securing funding, either directly or through third parties is also included in this category as part of the support for businesses as an integral form of support provided by business incubators. Support seeking financing and legal advice are found to be the most important service offered by the incubators. Public financing continues to be most prevalent when opening new incubators or maintaining existing incubators, as this study demonstrates. The tech industry is the sector with the most interest in incubators’ ecosystems, and young entrepreneurs are keen to start a business in this sector. To analyse the variable of financing that firms used during start-up within the business incubator, we use data from the survey and separate it into public or private.

To analyse entrepreneurship amongst young adults within incubators, we employ the age distribution proposed by GEM, where those identified as starting or running a new business are grouped by age into a younger age group (adults aged 18–34) and an older age group (aged 35–64) (Hill et al., 2023). Since project promoters’ average age in each incubator is known, we construct a synthetic variable classifying incubators as having significant young input when the incubator's average age is below 35 and incubators with an average age above 35 as not young. In our sample, 32 incubators, or 34,40 %, fall into the young category and 61 (65,60 %) are in the second category.

Analysis of business incubators’ characteristicsIn this section we examine the variables that characterise the incubators, encompassing annual budget; annual frequency of entrepreneurial events; training courses (transversal topics or support); monthly frequency of training courses (transversal topics or support); pre-incubator projects and workshops; pre-incubator or co-working spaces; whether the incubator offers free services, consulting sessions with experts or monitors the of pre-incubator projects’ activities; the proportion of companies that are currently continuing business activities; the percentage of graduated projects that obtained public financing; and which projects obtained private funding.

Support through access to investors, access to peers, help with team formation and direct funding from the programme could have a positive impact (Bone et al., 2019), which we link with our variables covering entrepreneurial events, training courses, co-working spaces and consulting sessions with experts. Some variables are quantitative in nature such as the impact of events and learning, mentorship, access to funding and collaborative network provided by the Circular Jumpstart acceleration programme for start-ups (Muchtar & Nalurita, 2023). In addition, mentorship programmes, entrepreneurship education and an emphasis on innovation and creativity through entrepreneurial universities and academia (Dhiman & Arora, 2024) as well as providing necessary resources for success such as expert-level technical assistance and a safe, empowering third space for collaboration (Palazzolo & Devasagayam, 2023) have also been found beneficial. Variable consulting sessions with experts highlighted the role of entrepreneur-coach in the context of a university-based accelerator (Mansoori et al., 2019).

Gaps remain in the services provided by the incubators such as operating practices, business accelerator forms, organisational structure, operations and outcomes, incubators performance and how they function within a structured framework (Kramer et al., 2023). Other scholars have explored how incubators’ programme design influences new ventures’ ability to access, interpret and process the external information needed to survive and grow. The target should be to design and operate such programmes based on theories and empirical research concerning firm-level entrepreneurial performance (Cohen et al., 2019).

To assess the survival of new businesses, we endeavour to identify the mechanisms that explain how incubators operate and their role in supporting entrepreneurship and innovation (Crișan et al., 2021), as well as practices and tools for sustaining start-ups’ innovation process and increasing their survival probability (Battistella et al., 2017). In addition to the more traditional success measure we introduce graduated projects that have obtained public financing, which was also considered by Zudaire and Alférez (2018).

Other research has examined start-ups receiving benefits linked to strategic business development acceleration in the areas of strategy and business model improvement, pitching, financing and strategic partnership (exit) development (Gutmann et al., 2019).

Investment can involve new tools such as private funding via mutual funds for qualified investors (Astapov & Zhdanov 2022) and companies’ financial priorities should generate sufficient resources to ensure start-up development (Kupp et al., 2017). Securing external support is a critical issue that determines business viability (de Klerk et al., 2024), and entrepreneurs must manage the tension between acquiring resources and preserving autonomy (Seidel et al., 2016).

Analysing the relevant variables from those detailed above allows us to test our first hypothesisH1. There is a connection between the age of the entrepreneurs in the incubators and the amount of financial support to the incubators

Sub-hypothesis The higher the age of the entrepreneurs in an incubator, the greater the financial support for the incubator

Fig. 1 shows that young incubators have smaller budgets that those with entrepreneurs over 35. Considering the older age profile of Spanish entrepreneurs, it seems logical that stronger incubators with larger budgets and more resources are overrepresented by more consolidated and competitive projects led by older entrepreneurs as networking, experience and market knowledge are key for such projects. Clear, though not significant, differences are found in the distribution, and the p-value of the chi-squared test is 0.117, which is very close to rejecting the null hypothesis at a 10 % significance level.

Fig. 2 shows the events held by incubators to foster entrepreneurship, revealing that incubators geared more towards a younger audience hold fewer events than those with older tenants. This indicates that young entrepreneurs are at a disadvantage because they access incubators with lower budgets that offer less activity such as networking or training. The difference, in this regard, is statistically significant at the 10 % level (p-value=0.078).

Fig. 3 shows that incubators with a higher proportion of young entrepreneurs offer fewer training opportunities or entrepreneurial support. It is also found that as entrepreneurs’ training is primarily offered outside of the incubator itself, it is difficult to assess the value of belonging to the incubator, at least in terms of access to training. However, as the p-value is 0.238 it is not considered to be a significant aspect of improving young entrepreneurship.

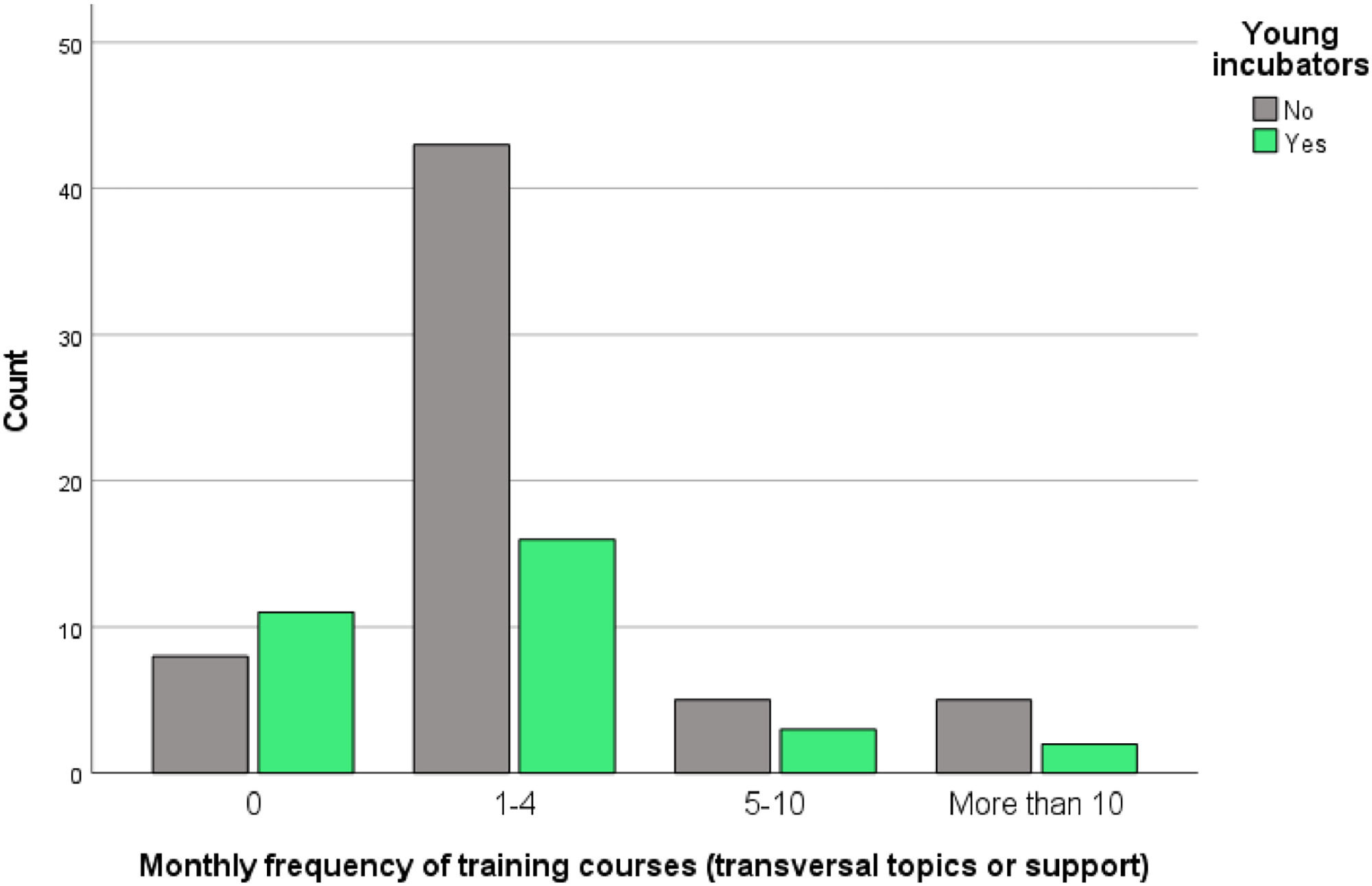

Fig. 4 reflects the monthly frequency of training courses. Once again, the younger group is at a disadvantage as the distribution of training courses in these incubators exhibits lower values. These differences are significant at the 10 % level (p-value = 0.054).

Fig. 5 shows that the frequency of training workshops for pre-incubated and incubated projects is higher for older age incubators, with a highly significant difference (p-value = 0.029). The variables of entrepreneurial events, training courses and workshops confirm the findings of (Bone et al., 2019; Muchtar & Nalurita, 2023; Palazzolo & Devasagayam, 2023).

The right hand figure in Fig. 6 shows that incubators offer consulting sessions with experts (p-value = 0.109), spaces for co-working (p-value = 0.074) and monitoring project activities (p-value = 0.067) with more frequency in older incubators. The left hand figure shows services offered for free to a greater degree in incubators are higher in older incubators (p-value = 0.172). According to all the variables we have analysed, we conclude that younger incubators offer a lower level of benefits, confirming the results of (Mansoori et al., 2019; Dhiman & Arora, 2024; Muchtar & Nalurita, 2023).

Incubators’ budgets favour older entrepreneurs, as does the frequency of events that support entrepreneurship. We highlight statistically significant characteristics of incubators such as the training courses on offer, their frequency and their transversal nature alongside the training workshops, spaces for co-working, consulting sessions with experts and monitoring project activities and free services. These are highly indicative and reveal how younger entrepreneurs are hampered in their entrepreneurial endeavours.

Plot 1 shows business incubators’ characteristics and their role in seeding and nurturing young entrepreneurs’ activities. We divided them into qualities of a business incubator that serve as seeds and those that provide relevant assistance.

Plot 1 Significant seeds for young entrepreneurs

Pertinent seeds for young entrepreneurs

Thus far, chi-squared tests have been used to determine which seeds are relevant for the characterisation of young entrepreneurial profiles in business incubators. However, for more research depth and quantitative robustness, we employ a logistic regression model that takes the age-related incubator classification as the dependent variable. This technique enables us to examine the impact of each of the nine seeds in Plot 1 on young entrepreneurial success. Due to the large number of explanatory variables included, we use a forward selection method.

We fit the model to all the individuals in our sample, with only one significant variable in the logistic model (Table 1): the impact of training workshops for projects.

To evaluate the results of the logistic regression model, it is advisable to consider the so-called confusion matrix (or classification table), which is a tabular representation of actual (observed) vs values predicted (by the model). This table contains four cells that correspond to true positive (TP), true negative (TN), false positive (FP) and false negative (FN) predicted values. Some important metrics can be defined from this information, encompassing the model's accuracy [(TP + TN) / Total], specificity [TN/(TN + FP)] and the sensitivity [TP / (FN + TP)].

Table 2 presents the associated classification table. The overall percentage of correct classifications in the chosen model is 65,9 %, with a sensitivity of 56,7 % and a specificity of 70,9 %. These are good results, considering the heterogeneity of the business incubators.

Other descriptors of young entrepreneurship in SpainThis part of our research examines young entrepreneurship by region, which sectors generate more interest amongst the young and whether they obtained financing for their projects. The subsequent recommendations we propose for public administrators are based on the analysis of these results.

Autonomous regionsWe next analyse the proportion of young entrepreneurship and that of entrepreneurs over 35 according to geography based on Spain's autonomous regions.

As shown in Fig. 7, most of the incubators in Spain have entrepreneurs over 35 years of age, which is consistent with the current profile for entrepreneurs in Spain as being older than other European countries nearby, where 80 % are between 25 and 54 according to GEM (Calvo et al., 2023).

Madrid and Galicia stand out regarding the number of entrepreneurs over 35 years of age. Notably, Madrid has the highest level of entrepreneurial activity in the whole country. The greatest concentrations of business and entrepreneurial activity are in Madrid, Catalonia and Galicia, where mature entrepreneurs prefer to engage in entrepreneurial activity.

Furthermore, incubators receive a greater level of support in Madrid and Catalonia, primarily through seminars and workshops (Rosado-Cubero et al., 2023), and this study demonstrates that these regions clearly support senior talent. The opposite is true in the Mediterranean, Valencia, Murcia and Castile-la Mancha, where young entrepreneurial talent is particularly prominent.

Notably considerable differences are found between youngsters from Madrid and Catalonia in terms of accessing business incubators due to the clear cultural differences of their university graduates. According to the GUESSS 2021 report (Ruiz-Navarro et al. 2021), Catalan universities have a high proportion of students that intend to start their own businesses in five years (23 % from Universidad de Girona and 18 % Universidad de Barcelona) and less see themselves working for a large company (12 % and 15 %, respectively). These figures are remarkably different for students from Madrid, who generally do not see themselves owning a business in the same time frame (Universidad Carlos III only 3.8 % and Universidad Rey Juan Carlos 13.8 %) and lean towards working for a large company in five years (37.8 % from Universidad Carlos III and 30.4 % from Universidad Rey Juan Carlos).

Economic sectorsWe begin by examining whether young people become entrepreneurs in the tertiary sector and the other two sectors.

Fig. 8 shows that older and younger incubators tend to focus on the tertiary sector. Notably, Spain is highly focussed on the service sector for a variety of reasons such as high production costs, low investment in research and development, less competition in many productive areas and related characteristics. This directs the focus towards the tertiary sector, which is a trend that young people are also following with entrepreneurial activity.

Project financingProject financing is an interesting variable that is, once again, found to be a hindrance for the young. As shown in Fig. 1, older incubators have larger budgets than those with entrepreneurs below the age of 35. Fig. 9 illustrates how projects led by mature entrepreneurs also gain more public and private funding. Securing public financial support is a highly competitive process.

The findings reveal that young entrepreneurs are at a disadvantage concerning business incubation. This study of how incubators are financed aligns with (Bone et al., 2019; Astapov & Zhdanov 2022; Seidel et al., 2016).

Quality and quantity of services provided by incubatorsFuncas establishes low, medium and high levels for incubators based both on the quality and quantity of the services provided. Once again, Fig. 10 shows that incubators geared towards young entrepreneurs are more likely to be in the low category.

Table 3 shows that 43.8 % of the young incubators are in the lower level of the Funcas classification, whilst only 28.3 % of older incubators are at this level. Furthermore, 36.7 % of the older incubators develop higher quality and quantity of activities and offer a greater number of services, while only 28.1 % of young incubators reach a high level of quality and a wide range of services, which is a novel variable analysed in this study.

Quality and quantity of services provided by incubators.

In this section we explore our second working

Hypothesis H2 Initiative is one of the qualities of business people that is more prevalent in entrepreneurs under 35.

Entrepreneurs’ personality traits have been explored at length (Kerr et al., 2018), and meta-analysis studies have highlighted significant associations between personality and entrepreneurship (Brandstätter, 2011). Nevertheless, the impact of founders’ personalities on the success of new ventures is largely unknown. We next demonstrate that founder personality traits are a significant feature of a firm's ultimate success (McCarthy et al., 2023). Some of the personality traits include self-efficacy and the ability to identify business opportunities (Paranata et al., 2023). The most recent GEM also indicated that specific personal characteristics can encourage enterprising activity, which is crucial for advancing contemporary economic activity (Calvo et al., 2023).

We examine whether young entrepreneurs have specific personality traits that can help us make suggestions for improving entrepreneurial models. We identify PI as a personality trait that is linked to young entrepreneurship, and after the age of 35, entrepreneurs also cite confidence and perseverance as essential. To increase the number of young start-up entrepreneurs, it is essential to understand the meaning of entrepreneurial intention, and the concepts of exploration and exploitation as mediating roles of entrepreneurial intention have also been analysed (Lee et al., 2022).

Recent research on how PI influences entrepreneurial intention amongst graduating students of tertiary institutions in Nigeria revealed a positive correlation (Ogba et al., 2022). Furthermore, personality traits (determination, discipline, locus of control, risk-taking and tolerance) have been found to stimulate young entrepreneurs’ entrepreneurial intentions (Cao et al., 2022).

PI refers to work practices defined as self-starting and proactivity that overcomes barriers to achieve a goal that sharpen entrepreneurship, alongside other traits such as innovation and work performance (Frese & Fay, 2001). Research into the influence of PI in social entrepreneurial venture creation among community-based organisations in Uganda found that PI in terms of proactiveness to be positively and significantly associated with new companies (Nsereko et al., 2018). PI was also found to influence entrepreneurial intention amongst graduating students in Nigeria (Ogba et al., 2022). Other research has demonstrated that potential female entrepreneurs are more sensitive to the complexity of PI compared with male entrepreneurs (Dal Mas & Paoloni, 2020). In addition, previous studies have highlighted the importance of in-group support in narrowing the gender gap in youth entrepreneurship (Weiss et al., 2023). In Spain, research using a decision tree model to determine the most relevant characteristic of entrepreneurs found high PI to be a relevant personality trait (Rosado-Cubero et al., 2022).

Entrepreneurs over 35 consider other personality traits to be valuable such as confidence and perseverance. The positive impact of entrepreneurs’ confidence is useful for managing stress and fear of failure (Srinivasan et al., 2023). The most potent factor was entrepreneur confidence, followed by cultural support and entrepreneur education (Owodunni, 2022); however, the impact of confidence changes with experience, wherein more experienced entrepreneurs are able to adapt to environmental changes (Cunningham & Anderson, 2018). Regarding perseverance, the prolonged wait until first revenue can be highly disappointing for entrepreneurs and challenges their perseverance (Vuong et al., 2015).

Entrepreneurs exhibit exploratory perseverance as reflected by a tendency to continuously explore broader sets of alternatives (Muehlfeld et al., 2017), and entrepreneurial persistence can be a malleable concept that changes over time (Pollack et al., 2019). Furthermore, entrepreneurial persistence via self-efficacy is positively correlated (Asante et al., 2022); therefore, entrepreneurs must have the grit, determination and perseverance to achieve their goals. However, entrepreneurs should remain aware that pressure can harm persistence with underperforming ventures (Zhu et al., 2021).

Venture growth is greater with high entrepreneurial persistence levels (Kawai & Sibunruang, 2023). Amongst young people, persistence is defined as commitment to a goal that has a direct effect on entrepreneurial persistence (Mohand-Amar et al., 2022). It is also related to affective commitment, while continuous commitment and risk-taking are peripheral conditions for entrepreneurship (Gabay-Mariani et al., 2023).

For the purposes of this study we asked incubator managers which characteristics define entrepreneurs, making a distinction between young (under 35) and old (over 35). Fig. 11 presents their answers, separated into those received from old and young incubators.

The left hand side of Fig. 11 shows that initiative is a quality that is rated more highly by incubators with young entrepreneurs, although it is also featured in the responses for over 35 s. On the right hand, we show that the most relevant personality trait recognised by older incubator managers is perseverance.

The chi-squared test reveals significant differences between young and old incubators when we focus on the personal characteristics of entrepreneurs who are over 35 (p-value = 0.047). The trait of confidence hardly features in the responses from incubators geared towards young entrepreneurs, although it is highly valued in the responses from older incubators. Older incubators detect high levels of confidence in entrepreneurs over 35, whilst those focusing on younger entrepreneurs do not value this trait highly, instead focusing on perseverance.

In contrast, no significant difference is found in the responses related to under 35 (p-value = 0.870), indicating that the personality traits of those under 35 are valued to the same degree in older and younger incubators. These results align with (Brandstätter, 2011), (Lee et al., 2022) and (Calvo et al., 2023).

DiscussionPrevious studies have analysed the long-term value that incubated companies acquire (Paoloni & Modaffari, 2022), which appears to be an extremely interesting area of exploration. In the case of failed businesses, recent studies show that entrepreneurial engagement of entrepreneurs after failures and of the role of culture are significant aspects of re-entry into entrepreneurship (Uriarte et al., 2023). In Fig. 12 we include data regarding incubated businesses’ survival rate and separate the data keeping the original classifications according to the incubator directors’ answers according to projects with either a prevalence of over 35 and those with under 35. It is notable that projects led by entrepreneurs over 35 survive longer; however, we also find the those led by under 35 also survive, according to the results.

Limited data collection hampered this study; therefore, incubator managers provided our data. Ideally, direct contact should be made with entrepreneurs in future research. This study focused on incubators rather than incubated businesses.

We also do not include a historical analysis to show variables’ changes over time, given the inability to compare longitudinal questionnaire responses. While including additional questions in the questionnaire could improve the information gathered, comparing the results over time remains a challenge and may not be worthwhile because it might not significantly improve the results.

ConclusionsThis study examines Spanish business incubators’ support of young entrepreneurs. To do so, we construct a synthetic variable to classify incubators into young old categories. Previous research has indicated that incubators that function as seeds in an entrepreneurial ecosystem can be useful for encouraging young people to start a business (Rosado-Cubero et al., 2023). This study examines the impact of multiple variables on incubators’ success. Budgets, training courses and consultations between entrepreneurs and experts are shown to be highly relevant concerns. We use 2023 data from the Funcas questionnaire ranking incubators (Blanco Jiménez et al., 2021) that include annual budget, annual frequency of entrepreneurship events, offer of training courses (transversal topics or support), monthly frequency of training courses (transversal topics or support), pre-incubated projects and workshops, spaces of pre-incubator or co-working and whether the incubator offers services for free, consulting sessions with experts or monitors pre-incubator projects’ activities. This study fills the gap concerning business incubators in Spain and their influence on helping young entrepreneurs.

Our analysis demonstrates that the statistically more relevant variable, as we expected, is entrepreneurship education, which can yield higher returns than subsidies. Fostering young entrepreneurship yields higher returns than fostering old entrepreneurship (Hincapié, 2020).

In Spain, most of the projects led by young people are incubated in business incubators with reduced budgets (Fig. 1) and the services offered are also limited (Figs. 4–7). Conversely, older incubators have larger operative budgets and offer a wide range of services, which also allows entrepreneurs to enjoy easier access to public and private financing (Fig. 9). Therefore, young entrepreneurs are at a disadvantage in terms of project financing.

We demonstrate that Madrid, Catalonia and Galicia have concentrated entrepreneurial activity and entrepreneurs over 35 prefer to conduct entrepreneurial activities in these regions. We also show that the tertiary sector is favoured by entrepreneurs of all age in Spain (Fig. 8). Finally, the proportion of low-quality incubators is higher in young incubators (Fig. 10).

In the final section of this study, the results demonstrate that the PI trait was rated higher by young incubator directors and was also mentioned by older incubator managers, also valuing other personality traits of confidence and perseverance.

Theoretical contributionsThis research makes several potential contributions to theories of management and incubators, providing theoretical insights into the age difference between entrepreneurs, and highlighting the relevance of age.

In accordance with the approach we developed to enhance the success of incubators (Rosado-Cubero et al., 2023), we contribute with a novel analysis of a set of variables that were determined to be significant and relevant that may help young entrepreneurs within an incubator that we call seeds. Recent research has validated the idea that incubators influence start-up success in diverse ways, encompassing key elements such as access to funding, mentorship programmes, collaborative workspaces and networking opportunities (Kehinde Feranmi Awonuga et al., 2024).

The success of training workshops for projects should also be noted among the variables studied. Previous publications have found that managerial training programmes for entrepreneurs are a substantial aspect of obtaining new skills, knowledge, insights, experiences and practice and attitude changes, which are essential for successful company leadership and management (Antonovica et al., 2023). Furthermore, an entrepreneurial learning model supported by a university entrepreneurship ecosystem and business incubators must be integrated for incubators’ success (Andriany et al., 2023). Our analysis confirms that the training programmes are crucial seeds for entrepreneurs, including workshops, courses and other such events.

This study demonstrates the challenges of private and public financing that young incubators face. This finding aligns with financial support models for the commercialisation of innovative business ideas (Narzullaev Shodiyor Eshpulatovich, 2024). The importance of public policies to support young entrepreneurs was previously highlighted by Zudaire and Alférez (2018). Furthermore, recent research has indicated that the government should improve pertinent support measures, enhance the development of business incubation platforms and encourage young people returning to their hometowns to start businesses (Liu et al., 2023). In addition, incubators should engage young entrepreneurs in local populations to retain expertise and valuable human resources (Moleiro Martins, 2023). Our contribution further validates one of the greatest needs that young people have when deciding whether to start up a business: financing.

This study also explores a second hypothesis, revealing the gap between young entrepreneurs and people over 35, which has been extensively investigated. Our contribution demonstrates the influence of PI among young entrepreneurs and that of perseverance among entrepreneurs over 35 as risk-taking generally decreases with older generations (Aydin et al., 2023). Previous research has demonstrated that business incubators have an important role for universities in collaboratively encouraging student creativity and innovation in entrepreneurship (Wardani et al., 2023). This investigation can be considered a precursor for future quantitative incubator investigations.

Practical implicationsMany incubators lack the services that are generally determined by budgetary issues. Therefore, we recommend increased public funding to support training and mentoring. Public institutions’ support of youth entrepreneurship can have a considerable influence on star-ups’ success and subsequent economic growth. This study demonstrates that the propensity for new entrepreneurship can vary considerably between age groups, providing insights for policy development to support and encourage under-represented groups in starting and running businesses, primarily young entrepreneurs.

Managers of incubators that operate in traditional sectors can understand the functioning of their work, its dimensions and the high influence that can lead a successful entrepreneurial ecosystem. Accordingly, incubator managers can meaningfully reference our results as a guide for developing organisational protocols and guidelines for respective incubators. Specifically, managers can reference these results to improve innovative ideas, promote access to knowledge, encourage innovation and promote internal talent.

In the ecosystem established by the government of South Africa, patriarchy and no access to land were found to be the major intersectional factors contributing to the poor participation of young women in entrepreneurship (Chauke, 2022). We determine that government intervention in the form of high-quality support programmes can stimulate opportunities for nascent and young business entrepreneurship (Cordier & Bade, 2023). Another example is the Finnish Higher Education Institution, which offers entrepreneurship education, events and competitions for students, should be increased and promoted more effectively (Torniainen, 2018).

After analysing the proportion of young entrepreneurs across Spain's autonomous regions, we recommend support for youth in all regions. Young entrepreneurs should be guided to operate in all economic sectors, which will retain the populations in those areas and decrease current trends of youth leaving certain areas. Our top recommendation is to implement measures to support entrepreneurship, regardless of the activities that young people want to undertake. Finally, financing for start-up projects must be prioritised for public investment.

Policy makers can support incubators and accelerators by providing funding, launching dedicated programmes and improving access to existing programmes (European Commission, 2019). The practical implications of this study can guide policy makers, entrepreneurs, investors and business incubator managers in shaping a supportive and dynamic start-up ecosystem in Spain.

The most practical policy recommendation for Spain is that public funding can help start-ups that are focused on innovation. Policy makers have continuously emphasised that greater provision of venture capital must be at the heart of entrepreneurial policies (Brown & Lee, 2019) and we recommend that this policy be applied in Spain. This study contributes to developing a favourable environment for young entrepreneurs in business incubators.

| Regarding Hypothesis 1: There is a connection between the age of entrepreneurs in incubators and the amount of financial support received by incubators. | |

|---|---|

| Variables | Authors |

| Annual budget | Novel variable |

| Annual frequency of entrepreneurial events | (Bone et al., 2019) |

| Offers and frequency of training courses (transversal topics or support) | (Bone et al., 2019; Muchtar & Nalurita, 2023; Palazzolo & Devasagayam, 2023) |

| Spaces for pre-incubator or co-working | (Bone et al., 2019) |

| Offer of free services | (Kramer et al., 2023; Cohen et al., 2019) |

| Consulting sessions with experts | (Muchtar & Nalurita, 2023; Dhiman & Arora, 2024; Mansoori et al., 2019) |

| Monitoring pre-incubator projects and workshop activities | Novel variable |

| Proportion of companies currently continuing activities | (Crișan et al., 2021; Battistella et al., 2017) |

| Proportion of graduated projects that have obtained public financing | (Zudaire & Alférez, 2018; Liu et al., 2023) |

| Which projects obtained private funding | (Bone et al., 2019; Gutmann et al., 2019; Astapov & Zhdanov 2022; Kupp et al., 2017; de Klerk et al., 2024; Seidel et al., 2016; Narzullaev Shodiyor Eshpulatovich, 2024) |

| Quality and quantity of services provided by the incubator | Novel variable |

| Regarding Hypothesis 2: Entrepreneurs’ age influences the extent to which they exhibit initiative. | |

| Initiative | (Frese & Fay, 2001)(Brandstätter, 2011; Nsereko et al., 2018; Kerr et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2022). (Ogba et al., 2022; Cao et al., 2022; Dal Mas & Paoloni, 2020; Rosado-Cubero et al., 2022; Paranata et al., 2023; Calvo et al., 2023; Aydin et al., 2023) |

Ana Rosado-Cubero: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Adolfo Hernández: Writing – review & editing, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Francisco José Blanco-Jiménez: Resources, Data curation. Teresa Freire-Rubio: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.