Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection is the cause of the so-called coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which has currently spread causing a global pandemic.1

There is little information about cutaneous involvement caused by this virus, mainly collected in an initial series of adult patients from Lombardy1 (maculopapular, urticariform, or varicelliform rashes) and isolated cases of petechial rashes,2 digital gangrene and livedoid lesions.3 We report a descriptive and multicenter case series collected in our setting.

During the week of 13th to 19th April 2020, all suspected cases of cutaneous lesions caused by COVID-19 from the Region of Murcia were collected by tele-consultation or visit to admitted patients. To do this, we requested primary care doctors to electronically report any cutaneous findings in patients with disease confirmed by diagnostic tests or in their cohabitants.

During the study period, 196 cases were confirmed by serology (Polymerase ChainReaction [PCR]) in our region. That means that from 1463 initial cases, a total of 1659 were reached at the end of data collection.

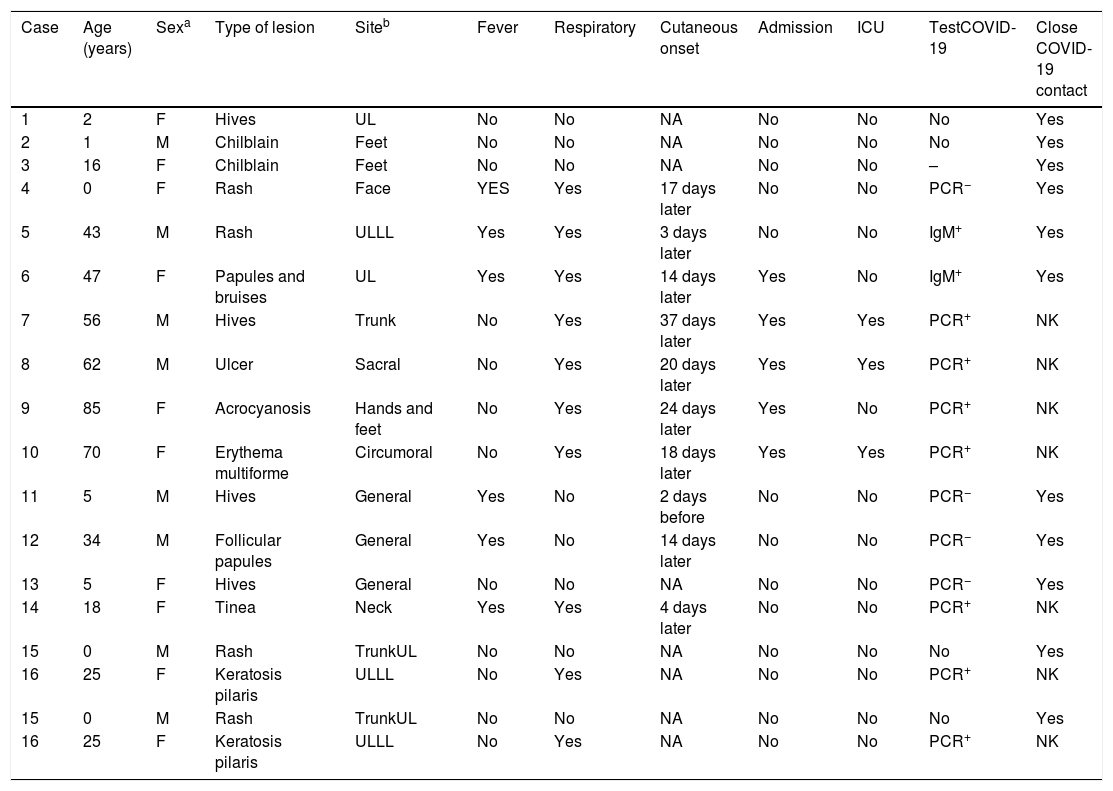

Throughout these 7 days, of the 86 cases initially assessed, 16 met the requirements of de novo cutaneous lesion development together with positive evidence of infection or close contact with cohabitants of COVID-19 disease confirmed by diagnostic tests (Table 1). The mean age of this group was 29 years (range: 8 months–85 years, median:21 years). 56% of cases occurred in women.

Demographic and clinical data of cases with COVID-19 or in close contact with confirmed cases.

| Case | Age (years) | Sexa | Type of lesion | Siteb | Fever | Respiratory | Cutaneous onset | Admission | ICU | TestCOVID-19 | Close COVID-19 contact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | F | Hives | UL | No | No | NA | No | No | No | Yes |

| 2 | 1 | M | Chilblain | Feet | No | No | NA | No | No | No | Yes |

| 3 | 16 | F | Chilblain | Feet | No | No | NA | No | No | – | Yes |

| 4 | 0 | F | Rash | Face | YES | Yes | 17 days later | No | No | PCR− | Yes |

| 5 | 43 | M | Rash | ULLL | Yes | Yes | 3 days later | No | No | IgM+ | Yes |

| 6 | 47 | F | Papules and bruises | UL | Yes | Yes | 14 days later | Yes | No | IgM+ | Yes |

| 7 | 56 | M | Hives | Trunk | No | Yes | 37 days later | Yes | Yes | PCR+ | NK |

| 8 | 62 | M | Ulcer | Sacral | No | Yes | 20 days later | Yes | Yes | PCR+ | NK |

| 9 | 85 | F | Acrocyanosis | Hands and feet | No | Yes | 24 days later | Yes | No | PCR+ | NK |

| 10 | 70 | F | Erythema multiforme | Circumoral | No | Yes | 18 days later | Yes | Yes | PCR+ | NK |

| 11 | 5 | M | Hives | General | Yes | No | 2 days before | No | No | PCR− | Yes |

| 12 | 34 | M | Follicular papules | General | Yes | No | 14 days later | No | No | PCR− | Yes |

| 13 | 5 | F | Hives | General | No | No | NA | No | No | PCR− | Yes |

| 14 | 18 | F | Tinea | Neck | Yes | Yes | 4 days later | No | No | PCR+ | NK |

| 15 | 0 | M | Rash | TrunkUL | No | No | NA | No | No | No | Yes |

| 16 | 25 | F | Keratosis pilaris | ULLL | No | Yes | NA | No | No | PCR+ | NK |

| 15 | 0 | M | Rash | TrunkUL | No | No | NA | No | No | No | Yes |

| 16 | 25 | F | Keratosis pilaris | ULLL | No | Yes | NA | No | No | PCR+ | NK |

The most common cutaneous reaction was hives (25%), followed by rashes (19%) and chilblain-like lesions (12%). Furthermore, we found another group of heterogeneous cutaneous lesions of remarkably diverse origin (infectious, vascular, inflammatory, traumatic, keratosis pilaris, and acrocyanosis). Thirty seven percent of cases associated fever and 56% respiratory symptoms, from cough to double pneumonia.

Unlike the series reported in Lombardy1 in which the most common cutaneous manifestation was erythematous rash, hives was the most common finding in our series. Previous studies showed that the most common cause of hives in children is infections, especially those of the respiratory tract.4

Keratosis pilaris is a common finding in children with atopic diathesis. We have found no evidence in the scientific literature of keratosis pilaris onset in patients with COVID-19. We do not know the mechanisms that may justify this finding in the context of COVID-19 disease.

One of the findings in our series is acrocyanosis. This sign reflects the peripheral hypoxia in probable relation to the thrombotic phenomena that have been described in the disease, both cutaneously3 as well as in other organ's vessels, including the lungs, heart, or brain, or by processes such as disseminated intravascular coagulation.5 In our case, we observed this finding in a patient with respiratory failure who required hospital admission.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, a restricted access to diagnostic tests, which excluded cases that presented with guiding symptoms of COVID-19, but which were not confirmed by PCR or serology; on the other hand, the elective use of tele-dermatology has made it difficult to take biopsies of these lesions.

More studies are needed that collect cutaneous manifestations in patients with COVID-19. Knowledge of these cutaneous reactions and study of the temporal patterns of onset of these findings could help to identify patients without other symptoms of this disease, especially in those regions where diagnostic tests are not available.

The authors wish to thank doctors Joaquín López, Javier Ruiz, José Pardo, Inmaculada de la Hera, Carolina Pereda and Marisa Cáceres for sharing with us the cases they have treated for the preparation of this article.

Please cite this article as: Pérez-Suárez B, Martínez-Menchón T, Cutillas-Marco E. Hallazgos cutáneos en la pandemia de COVID-19 en la Región de Murcia. Med Clin (Barc). 2020;155:41–42.