The arts in general1,2 and music in particular, have been considered a complementary medical treatment for the management of many ailments.3–6 Opera is a genre of theatrical music in which a scenic action is harmonized, sung and has instrumental accompaniment. It is an art form in which singers and musicians perform a dramatic work combining text (libretto) and musical score, usually in a theatrical setting. Opera has its origins in Italy during the late 16th century. Jacopo Peri is often credited with creating the first opera, Dafne, in 1598; later in 1607, Claudio Monteverdi opened his L’Orfeo, still performed nowadays. Richard Wagner coined the term Gesamtkunstwerk (translatable as a total work of art), to refer to a type of work of art that integrated the six arts: music, dance, poetry, painting, sculpture, and architecture. In Spain during the late 17th century, zarzuela started as a musical genre that combines operatic and theatrical elements with traditional Spanish music, dance, and folklore.

The perception of disease and patients, and of doctors, has evolved in time and can be traced in different artistic forms. Up to early in the 19th century, tuberculosis was considered a hereditary disease, associated with family and poverty. This vision started to change on March 24, 1882, when Robert Koch (Clausthald-Zellerfeld 1843 – Baden-Baden 1910) announced to the Berlin Physiological Society his discovery of the cause of tuberculosis. Three weeks later, on April 10, Koch published an article entitled “Die Atiologic der Tuberkulose”.7 News spread quickly beyond medical and scientific sources, and lay media started to assimilate this new evidence.

A similar pattern could be observed in the 1980s when the spread of AIDS/HIV created havoc. AIDS was first diagnosed in 1981. In 1983, Françoise Barré-Sinoussi and Luc Montagnier at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, France, identified the virus that causes AIDS, by culturing T cells from a lymph node biopsy from a 33-year-old homosexual French patient with lymphadenopathy and other symptoms that can precede AIDS. They originally called it lymphadenopathy associated virus (LAV), although later it was termed human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).8

This research aimed to analyze the opera repertoire in terms of contents of characters with tuberculosis and AIDS/HIV, and their determinants.

MethodsA systematic search was performed of the historical opera repertoire exploring musical characteristics and performing roles, and their determinants related with patients and doctors on tuberculosis and AIDS/HIV. All variables were tabulated and formally analyzed using the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidance for reporting observational research.9

A systematic search was performed in PubMed including printed and online resources to identify operas with performing roles of “patients”, “doctors”, “physicians”, and/or specific medical conditions. This search was extended and confronted with individual conversations with reputed (or not) opera experts and enthusiasts, plus a bibliographic search of specialized literature in English and non-English literature (i.e.: French, German, Italian or Spanish languages). Given some intrinsically loose definitions (opera vs. opéra-ballet, operetta, pièce lyrique, saynète, singspiel, zarzuela, musical, rock musical, etc.), it was considered as denominator the latest list of operas available online,10 whose authors report that it was compiled by consulting lists of great operas, by recognized authorities in the field of opera, and selecting all of the operas which appeared on at least five of these (i.e. all operas on a majority of the lists). Further details on methodology are available elsewhere.11 The following fields were extracted: opera characteristics (title, author, year and place of opening), singer characteristics (gender and voice register/chord), and medical specialty. Opera features a diverse range of human registers, each with distinct characteristics and roles. On the one hand, female chords are soprano, mezzo-soprano and contralto. The soprano voice, often the leading female role, possesses a bright and high-pitched timbre. The mezzo-soprano, slightly lower in pitch, lends depth and complexity to female characters. The contralto voice is the lowest female voice, providing richness and gravity. On the other hand, male chords are tenor, bariton and bass. The tenor, with its clear and soaring quality, typically portrays heroes or romantic leads, while the baritone, a versatile and middle-range voice, embodies a variety of characters, from villains to fathers. The bass voice, with its deep and resonant tones, often represents authoritative figures or antagonists. Together, these voices create the intricate vocal tapestry of opera, conveying emotions and narratives through their unique vocal qualities and dramatic interpretations. Counts and frequency distributions are presented. Formal statistical testing of proportions was by Chi2p values. No Ethics Board approval or informed consent were deemed required.

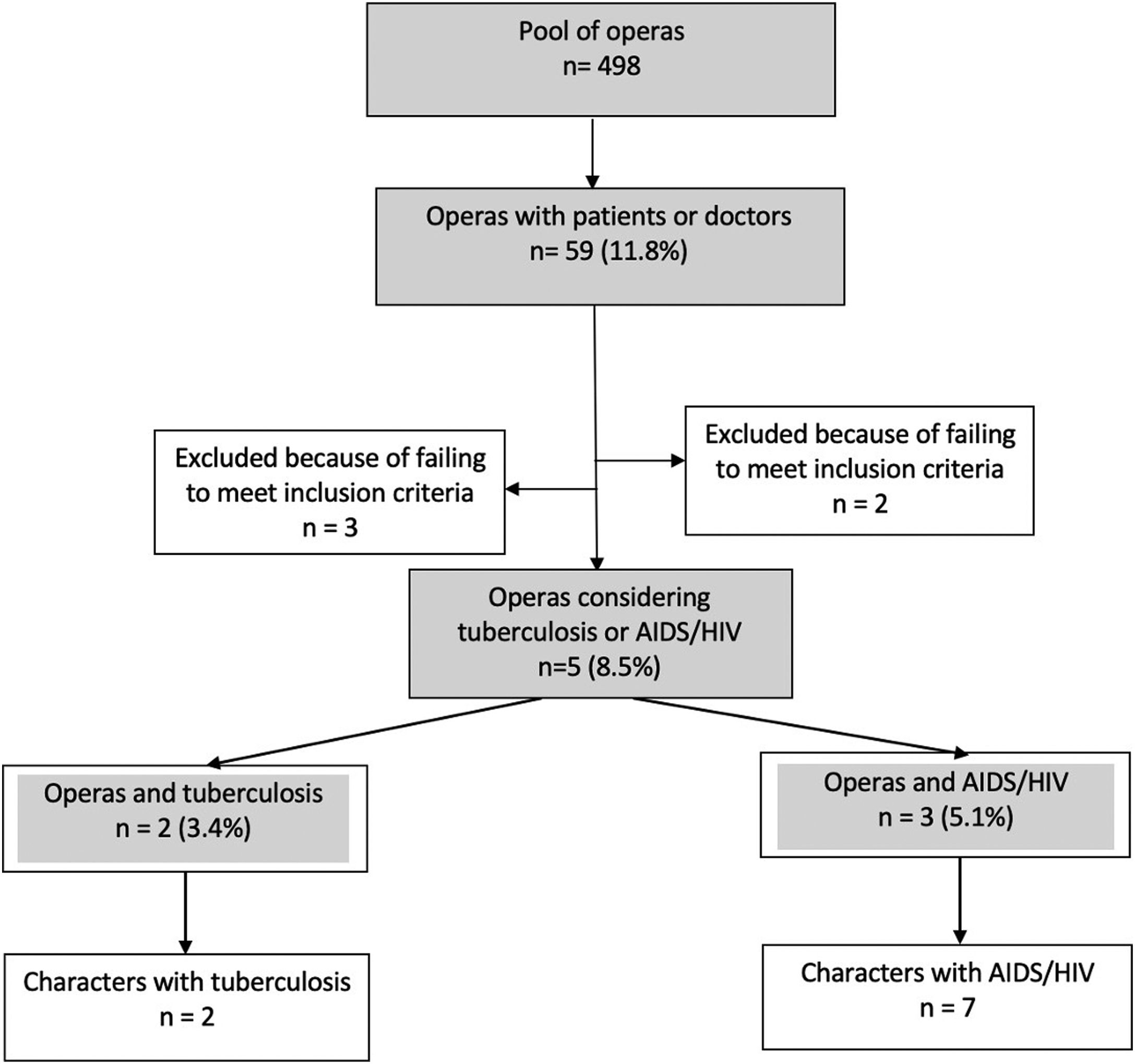

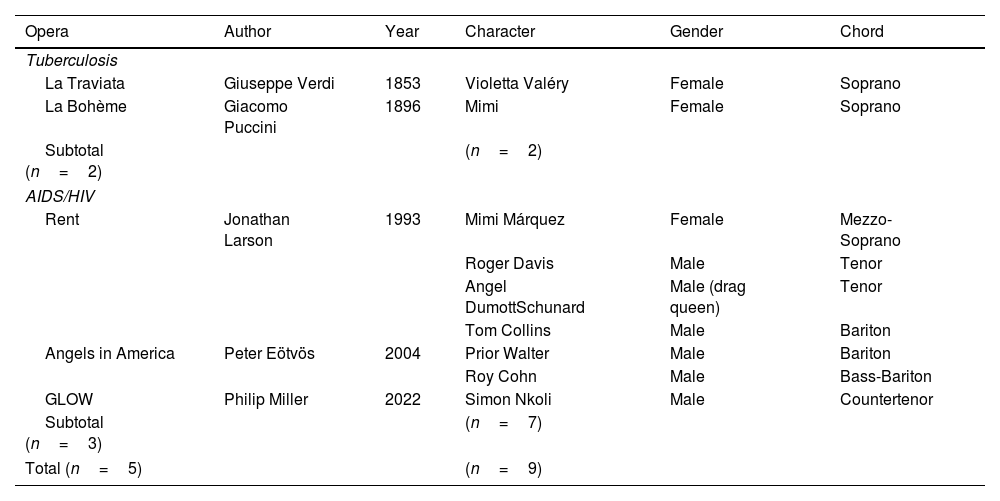

ResultsFrom 1597 to date, 498 operas have been identified, and 59 (11.8%) depict characters of either patients or doctors (Fig. 1). Out of these 59 operas depicting characters of patients or doctors, only two (3.4%) include two characters with tuberculosis (La Traviata, and La Bohème), and three (5.1%) operas include seven characters with AIDS/HIV (Rent, Angels in America and GLOW) (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

Descriptive characteristics of operas (n=5) with characters (n=9) with tuberculosis or AIDS/HIV.

| Opera | Author | Year | Character | Gender | Chord |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tuberculosis | |||||

| La Traviata | Giuseppe Verdi | 1853 | Violetta Valéry | Female | Soprano |

| La Bohème | Giacomo Puccini | 1896 | Mimi | Female | Soprano |

| Subtotal (n=2) | (n=2) | ||||

| AIDS/HIV | |||||

| Rent | Jonathan Larson | 1993 | Mimi Márquez | Female | Mezzo-Soprano |

| Roger Davis | Male | Tenor | |||

| Angel DumottSchunard | Male (drag queen) | Tenor | |||

| Tom Collins | Male | Bariton | |||

| Angels in America | Peter Eötvös | 2004 | Prior Walter | Male | Bariton |

| Roy Cohn | Male | Bass-Bariton | |||

| GLOW | Philip Miller | 2022 | Simon Nkoli | Male | Countertenor |

| Subtotal (n=3) | (n=7) | ||||

| Total (n=5) | (n=9) | ||||

The first identifiable character with tuberculosis was Violetta Valéry in La Traviata, by Giuseppe Verdi, opened in Teatro La Fenice of Venice, Italy, in 1853. Violetta is a courtesan (prostitute) who has tuberculosis and ultimately sacrifices her own happiness to protect the reputation of the man she loves. She dies while closing the final curtain.

Mimi in La Bohème by Giacomo Puccini, opened in Teatro La Scala di Milano, Italy, in 1896. She is a young woman who is struggling with tuberculosis among Rodolfo and his friends, all bohemian artists. Mimi ultimately also dies from the disease.

From 1896 to date, no other characters with tuberculosis are identifiable in opera.

Opera characters with AIDS/HIVFurther, three (5.1%) operas include 7 characters with AIDS/HIV, namely:

Rent, by Jonathan Larson, opened at New York Theatre Workshop, New York, USA, in 1993, was loosely based on Puccini's La Bohème. Within its numerous cast, it includes four characters identified with AIDS/HIV: Mimi Márquez, an erotic dancer and drug addict with HIV; Roger Davis, a songwriter-musician who is HIV positive and Mimi's boyfriend; Angel Dumott Schunard, a drag queen percussionist with AIDS; and Tom Collins, a gay, part-time philosophy professor at New York University and anarchist with AIDS.

Angels in America, by Peter Eötvös, opened at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris, France, in 2004. This opera made its US debut in 2006 at the Stanford Calderwood Pavilion in Boston, Massachusetts. It is based on the Tony Kushner play of the same name, and tells the story of the AIDS epidemic in the United States in the 80s and 90s. The main character is Prior Walter, a gay man with AIDS who experiences various heavenly visions. It also casts Roy Cohn, a gay lawyer that contracted HIV and the disease has progressed to AIDS, which he insists is liver cancer to preserve his reputation.

Finally, GLOW: The Life and Trials of Simon Nkoli, by Philip Miller, opened at Linden Studio, in Johannesburg, South Africa, in 2021. GLOW is self-labelled as a vogue-opera, based on the life of the flamboyant queer activist and freedom fighter, Simon Nkoli who lead the struggle for the acceptance of LBGTIQ rights in his native South Africa. It tells the story of the gay rights and anti-apartheid activist through a fusion of disco, hip hop, rap, protest songs, opera, drag culture and film. Simon Nkoli died in 1998 due to complications from HIV/AIDS.

Joint quantitative analysisAll five operas explored the languid beauty in women or homosexual men in tuberculosis (two sopranos) and in AIDS/HIV (one mezzo-soprano, one countertenor, two tenors, two baritons, and one bass). While 100.0% of characters with tuberculosis are women, 85.7% of those with AIDS/HIV are men (p=0.006), a blatant gender bias trend against women and also against men who have sex with men. Further, there is a trend for “softer” voice chords among these characters, sopranos in women and countertenor/tenors in AIDS/HIV (p<0.001).

Of note, since Dafne by Jacopo Peri in 1597, it took 180 years to appear the first patient/doctor as character, in 1777 with Joseph Haydn's Il mondo della luna; and it took 256 years to appear the first patient with tuberculosis, in 1853 with Giuseppe Verdi's La Traviata (Fig. 3). However, from the discovery of the cause of AIDS, it took only 10 years to appear a first patient as character, in Jonathan Larson's Rent. Finally, among the authors of operas depicting patient or doctor characters, kudos to Giuseppe Verdi, and Giacomo Puccini for considering tuberculosis and to Jonathan Larson, Peter Eötvös, and Philip Miller for considering AIDS/HIV as an opera topic (Fig. 4).

The patient toll and disease burden of tuberculosis and AIDS/HIV remains high in the 21st century.12–14 Globally in 2019, there were 1.18 million deaths due to tuberculosis and 8.50 million incident cases of tuberculosis among HIV-negative individuals. Among HIV-positive individuals, there were 217,000 deaths due to tuberculosis and 1.15 million incident cases in 2019.15 It is estimated by WHO that one-third of the world's population, or about 2 billion people, have latent tuberculosis; and 38 million people were living with HIV in 2021. While the number of new HIV infections has decreased in recent years,16 AIDS-related illnesses continue to be a major cause of death in many parts of the world, especially in sub-Saharan Africa.

In 400 plus years of opera history, totalling 498 works, only in five they included characters with either tuberculosis or AIDS/HIV; on the contrary, other conditions abound in operas covering Family Medicine and Generalists, Psychiatry, Surgery, Respiratory, Nutrition, or Cardiology, and single operas are also attributable to Ophthalmology, nurses and Pharmacy.11 Available definitions are blurred on what is meant by the “languid beauty of tuberculosis”. Tuberculosis was often referred to as a “romantic” or “beautiful” disease in the 19th century and earlier, particularly in literature and the Arts. This portrayal of tuberculosis as a desirable or attractive condition was often linked to the belief that the disease was a result of an excess of emotion or sensitivity, and that it was associated with creativity and artistic talent. For some, the pale skin and haemoptoic cough and sputum could drive sexual impulse. The idea of the “languid beauty of tuberculosis” may refer to this romanticized portrayal of the disease. It remains to be seen if the term applies to AIDS/HIV.17,18

Tuberculosis has been known by various names throughout history, including “consumption” and “phthisis,” and it has been a significant cause of illness and death for thousands of years.

Johann Lukas Schönlein (Bamberg 1793 – Bamberg 1864) is credited with providing the first detailed descriptions of the disease. In 1839, Schönlein published a groundbreaking treatise in which he described the characteristic symptoms and pathological changes associated with tuberculosis. As the founder of modern bacteriology, Robert Koch identified the cause of tuberculosis in 1882, and specific causative agents of cholera, and anthrax and gave experimental support for the concept of infectious disease. We are told his discoveries were highly publicized in the contemporary lay press. Of interest, Violetta Valèry in La Traviata, opened in 1853 could not infect other characters, as individuals from a poor origin could not be contagious to other social classes and airborne contagion was not considered, as it was widely believed that tuberculosis was an inherited disease. However, in La Bohème opened in 1896, Mimi's illness is stigmatized during the opera, as tuberculosis after Koch was finally considered contagious. People with tuberculosis were often isolated and ostracized in order to prevent the spread of the disease, and they faced discrimination and social stigma as a result. Mimi's illness is a central theme and a key factor in the storyline, and her death from tuberculosis is a poignant and emotional climax moment in the opera. Similar issues were later seen on the three operas contemplating AIDS/HIV, were fear, panic, intolerance, rejection, and social stigma were repeated, yet this time when confronting disease in a female prostitute, drag queens and else. Overall, doctors dealing with both conditions show little empathy for their patients, perhaps with the honourable exception of Dottore Grenvil in La Traviata.

This research reports a blatant gender and chord bias.19 All opera characters with tuberculosis are female, all sopranos. Au contraire, there are significantly many more men, and tenors and countertenors among opera characters with AIDS/HIV, than expected from the distribution in all previous operas depicting patients or doctors. Global Burden of Disease (GBD) estimates for 2019 show a worldwide predominance of male tuberculosis deaths (760,972 in men vs. 418,793 in women), while AIDS deaths are virtually even (435,394 in men vs. 428,443 in women).20 Overall, this gender bias first described in opera in here, likely is affecting literature and other Arts, and it contributes to sustain stereotypes and stigma against patients suffering tuberculosis or AIDS/HIV. In search for equal rights, it is most interesting to find no female doctors yet within the entire opera repertoire. This major signal of gender discrimination, on the views of the public and composers, persists well within current times. Hopefully, new composers might correct this absence.21

Strengths and limitationsThis research has some strengths, including novelty with up-to-date information, comprehensiveness, and the direct possibility to counterfact and confront all findings from its sources, and generate healthy discussions and engage in pleasurable conversations. However, some limitations can also be noted. With all intention to be exhaustive, there is no full agreement on how many operas there are, while new authors constantly create new additions for consideration; therefore, some roles and characters might have been overseen. Scientific definitions cannot be applied literally to a genre like music/opera, as the frontier in between Arts and Medicine can be loose.

Singing in most patients, and particularly in those with respiratory conditions, is safe and brings several clinical benefits.22–24 The opposite has been assessed scarcely. Paraphrasing Osler again, “He who sees patients and cannot talk to them about arts and opera, travels uncharted territories…”. More humanism in Medicine never hurts, au contraire it likely helps patients, undergraduate and postgraduate students, and doctors.25

Many consider there is an urgent need to rehumanize Medicine.26,27 Clinical practice must include non-technical care to further relieve suffering and sustain a partnership of patients and doctors against disease.28 Physicians train extensively to relieve suffering via pathophysiology, yet often there is neglect of other basic human needs. Re-humanizing the doctor–patient framework should help to support human connections of doctors and patients, and the arts might help.29 The words of José de Letamendi (Barcelona 1828 – Madrid 1897) are more needed than ever, that is: “The doctor who only knows medicine; He doesn’t even know medicine”.

Other works for considerationFor the record, some creations were considered, but rejected, for inclusion in this opera review: three alleged on tuberculosis and two on AIDS/HIV (Fig. 1).

On the one hand on tuberculosis, in Les Contes d’Hoffmann, by Jacques Offenbach, opened in Paris in 1881, during the third act, we are introduced to Antonia, another failed love of Hoffmann. Some have argued she might have tuberculosis; but with all likelihood, Antonia has a cardiac arrhythmia, perhaps mitral valve prolapse,30 which include fragility, dyspnoea, anxiety, and exhaustion, and occasional arrhythmias; sudden cardiac death occurs rarely, but has been reported. And, same applies to two operas by Ruggero Leoncavallo, I Medici, opened at the Teatro Dal Verme in Milan, Italy in 1893, and his La Bohème, opened at the Teatro La Fenice, of Venice, Italy in 1897, were also rejected; the former refers to cough only, and the later is based also on Scènes de la vie de bohème as the homonymous by Puccini, but focuses mostly on poverty not disease, and is hardly ever represented.

On the other hand, on AIDS/HIV, The Lisbon Traviata, by McNally must be considered a theatre play with songs, not opera. Similar to Violetta's consumption in Verdi's La Traviata, AIDS in The Lisbon Traviata, by means of humour and wit, expresses profound truth about the human condition. Both Traviatas are, after all, about love. Another rejection is The AIDS Quilt Songbook, intended to honour the lives of those lost to HIV/AIDS and to celebrate the ongoing fight against the disease; although some media reports label it as an opera, it is an ongoing collaborative song-cycle with subsequent additions, but without a theatrical script, ergo not an opera.

ConclusionsTo conclude, only a handful of operas depict characters of patients with tuberculosis or AIDS/HIV, with a blatant gender bias trend against women and also against men who have sex with men. A greater knowledge of opera and the Arts might contribute to further humanizing modern Medicine.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process: Not used.

Ethical approvalI fully endorse all Medicina Clínica standards.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestJBS is a bariton in the Opera Choir at the Teatre Principal, Palma, Spain. There are no other conflicts of interest to declare.