The objective was to evaluate the consumption of fish in pregnant women and its association with maternal and infant outcomes.

Material and methodsIn this observational study carried out at the La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital in Valencia, 300 pregnant women participated. The participants were divided into 2 groups according to their fish consumption during pregnancy for comparison. The χ2 test or ANOVA test were applied for comparisons for qualitative and quantitative variables respectively.

ResultsIt was observed that 49% of women consumed adequate amounts of fish during pregnancy (2 or 3 weekly servings). Significant differences were observed for iron supplementation (higher in women with inadequate fish consumption), threatened pregnancy loss (higher in women with inadequate fish consumption), infant size (better in women with adequate fish consumption), and arterial O2 pressure (better in women with adequate fish consumption). In regard to the other components of the dietary pattern, no differences were observed but the adequacy of intake for grains and white meat was very poor (less than 5.0%).

ConclusionsHalf of the women met the recommendations for fish intake during pregnancy and presented an overall healthier eating pattern but without statistical significance.

Evaluar el consumo de pescado en mujeres embarazadas y su asociación con la salud materno-infantil.

Material y métodosEn este estudio observacional llevado a cabo en el Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe de Valencia participaron 300 mujeres embarazadas. Las participantes se dividieron en dos grupos según su consumo de pescado durante el embarazo para comparar. Para las comparaciones de variables cualitativas y cuantitativas se aplicaron la prueba de χ2 o la ANOVA, respectivamente.

ResultadosSe observó que el 49% de las mujeres consumieron cantidades adecuadas de pescado durante el embarazo (2 o 3 raciones semanales). Se observaron diferencias significativas para la suplementación con hierro (mayor en mujeres con consumo inadecuado de pescado), amenaza de pérdida del embarazo (mayor en mujeres con consumo inadecuado de pescado), tamaño del bebé (mejor en mujeres con consumo adecuado de pescado) y presión arterial de O2 (mejor en mujeres con consumo adecuado de pescado). En cuanto a los demás componentes del patrón dietético, no se observaron diferencias, pero la adecuación del consumo de cereales y de carnes blancas fue muy pobre (menos del 5,0%).

ConclusionesLa mitad de las mujeres cumplían con las recomendaciones de consumo de pescado durante el embarazo y presentaban un patrón alimentario globalmente más saludable, pero sin significación estadística.

Adequate nutrition pregnancy is essential during the preconception period, pregnancy, and lactation to guarantee maternal–fetal health.

Fish can be a great source of protein, iron, zinc and omega-3 fatty acids which are crucial nutrients for fetal growth and development.

Half of pregnant women presented adequate fish intakes during pregnancy.

Women with adequate fish intakes during pregnancy reported a healthier eating pattern.

Pregnancy is a stage in a woman's life in which nutrition acquires an even more pointed relevance as maintaining a good nutritional status is an important component of a healthy lifestyle and a healthy baby, therefore, the diet of pregnant women should not be neglected. The foods that should be present in adequate amounts at this stage are cereals, legumes, fruits, vegetables, nuts, oils and animal products if the woman desires, as their intake is not necessary to have a healthy diet.

On average, each Spaniard consumed 22.72kg of fishery products during the 2021 year, which is an 8.5% (2.21kg) decrease from 2020, when domestic consumption intensified due to individuals staying longer in their homes.1 However, it is 0.8% higher than the consumption reported during 20191 which goes against the trend observed in the previous decade when the consumption of fish decreased yearly from 27.3kg in 2010, to 26.4kg in 2014, and 23.73kg in the 2015–2017 period.2 The fish consumer profile corresponds to households made up of couples with middle and older children, adult couples without children and retirees.1 The intensive profile in the purchase of fishery products corresponds to a household of high and upper-middle socioeconomic class, as well as middle class, for its part, the lower socioeconomic class, is the one who buys the category less intensively.1

Fish is a source of good quality protein, containing all essential amino acids as well as sulfur amino acids (cysteine and methionine). It is also a good source of vitamins B, A and D, especially the fattier species.3 Fish is an excellent source of N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFAs), especially docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA).3 These are dietary fats incorporated in many parts of the body, with an array of health benefits and essential for proper fetal development including the growth and development of the central nervous system in fetuses and infants.3

The benefits observed associated with adequate fish consumption during pregnancy due to its role as a source of n-3 PUFAs have not been observed for PUFA supplementation, these benefits have been seen only when n-3 PUFAs are obtained directly from their food source and not in the form of supplements, which makes us think that the consumption of the whole food source is the best option because of the amount of beneficial nutrients it contains.4

However, not all are benefits as growing evidence suggests that prenatal exposure to heavy metals through the maternal diet could have great influence on the neurological and physical development of fetuses and infants.5 Mercury is a ubiquitous environmental toxic substance, the most common heavy metal found in food sources, with adverse results for health.5 It is not possible to reduce the concentration of mercury in fish through preparation or cooking methods.5 As a result, fish consumption constitutes the main source of mercury in humans.5

Considering the importance of fish in the dietary pattern of the studied population and its possibly contradictory and dose-dependent effects of maternal–fetal health, this study aimed to evaluate the consumption of fish in pregnant women and its association with maternal and infant outcomes.

Participants and methodsDesignThe study is a retrospective study of maternal dietary habits during the pregnancy and their effect on newborn outcomes. It was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital (CEIC 2014/0116). All participants gave their informed consent, which included a confidentiality agreement according to the Protection of Data of Official Nature Organic Law 15/1999 of December 13.

SampleThe sample size calculation made using the Ene 3.0 program with a confidence level of 95%, a margin of error of 5%, an estimated prevalence of adequate fish intake of 25% for our population, yielded a required sample size of 289 women. Initially a sample of 377 women, who had just given birth to a live singleton at the La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital of Valencia and had not been yet discharged from the Maternity Wards were invited to participate in the study. The women were informed about the study and then asked if they would like to participate. Those who answered affirmatively were asked to complete a written informed consent. 300 women accepted and were included in the study, for a participation rate of 79.5%.

Data on the mother's socio-demographic characteristics (age, education, employment status), habits during pregnancy (smoking, self-medication, physical activity, supplementation, diet), anthropometric data (maternal height, maternal weight gain, infant length, infant weight, infant classification, infant head circumference), maternal and child medical history (number of children, previous pregnancies, threatened preterm labor, threatened pregnancy loss, premature rupture of membranes, anxiety or depression, urinary tract infection, asthma, digestive diseases, gestational diabetes, hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, preeclampsia, anemia, post-partum anemia, perineal tear, cesarean section, fetal distress, nuchal cord, fetal malformations, infant sex, Apgar 5′, arterial pH, arterial CO2 pressure, arterial O2 pressure, venous pH, venous CO2 pressure, venous O2 pressure, infant admitted to Neonatology Unit, infant admitted to PICU) was collected. Data was collected by way of a direct and personal interview by a trained dietician and the later review of the women's and newborns’ clinical history records. In relation to dietary habits, the “KIDMED”,6 “MEDAS”7 and “MedDietScore”8 questionnaires were used.

AnalysisThe χ2 test or ANOVA test were applied for comparisons for qualitative and quantitative variables respectively. All analyzes were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 26 software, considering as significance level p<0.05.

ResultsOf the 377 women offered participation, 300 accepted and were included in the study.

The women studied were divided into two groups, “adequate” (2 or 3 servings per week) and “inadequate” according to their fish intake. This cutoff point was established taking into account the recommendations from the Agencia Española de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición (AESAN) recommendations for the general Spanish population,9 and the recommendations specifically for pregnant women of the American Academy of Obstetricians (ACOG) and the Federación Española de Sociedades de Nutrición, Alimentación, y Dietética (FESNAD). The AESAN Scientific Committee recommends consuming at least 2 servings/week of fish (1–2 servings/week of oily fish).9 ACOG recommends the consumption of 2–3 servings of fish per week in pregnant women.10 FESNAD does not have individual recommendations for fish intake but includes this food group within “protein foods” (meat, fish, eggs, legumes) for which the recommendation during pregnancy is two daily servings.11 Both agencies recommend avoiding raw or undercooked fish and those higher in mercury content.

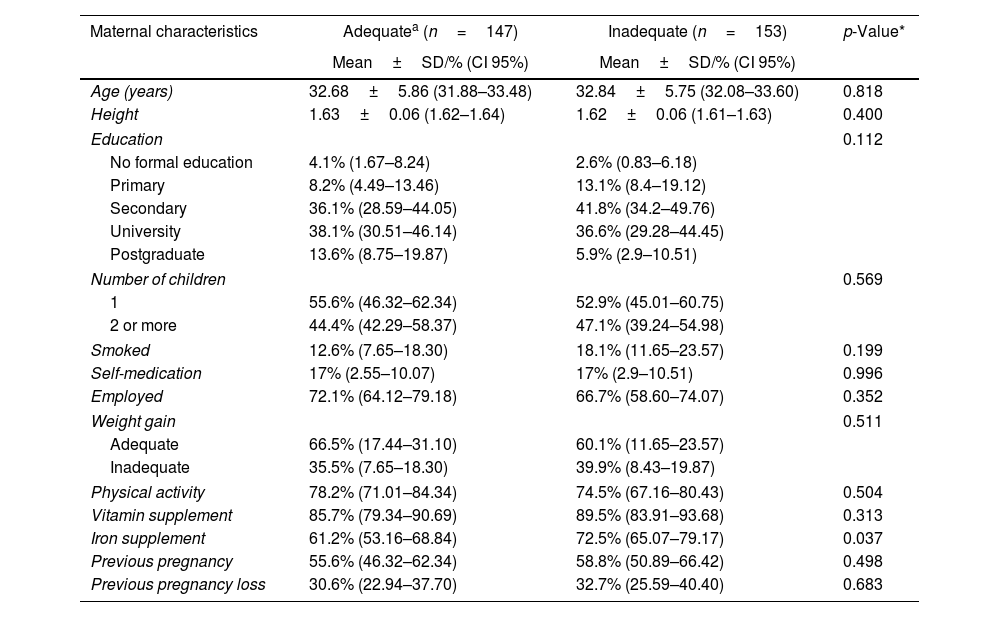

As can be seen in Table 1, this study identifies around half (49%) of the women studied presented an appropriate (2/3 servings per week) fish intake during pregnancy. Both groups of women had an average age around 32 years old. In relation to height, education, number of children, smoking status, self-medication, employment, weight gain, physical activity, and previous pregnancies, no significant differences were observed.

Maternal characteristics during pregnancy in relation to weekly maternal fish intake.

| Maternal characteristics | Adequatea (n=147) | Inadequate (n=153) | p-Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD/% (CI 95%) | Mean±SD/% (CI 95%) | ||

| Age (years) | 32.68±5.86 (31.88–33.48) | 32.84±5.75 (32.08–33.60) | 0.818 |

| Height | 1.63±0.06 (1.62–1.64) | 1.62±0.06 (1.61–1.63) | 0.400 |

| Education | 0.112 | ||

| No formal education | 4.1% (1.67–8.24) | 2.6% (0.83–6.18) | |

| Primary | 8.2% (4.49–13.46) | 13.1% (8.4–19.12) | |

| Secondary | 36.1% (28.59–44.05) | 41.8% (34.2–49.76) | |

| University | 38.1% (30.51–46.14) | 36.6% (29.28–44.45) | |

| Postgraduate | 13.6% (8.75–19.87) | 5.9% (2.9–10.51) | |

| Number of children | 0.569 | ||

| 1 | 55.6% (46.32–62.34) | 52.9% (45.01–60.75) | |

| 2 or more | 44.4% (42.29–58.37) | 47.1% (39.24–54.98) | |

| Smoked | 12.6% (7.65–18.30) | 18.1% (11.65–23.57) | 0.199 |

| Self-medication | 17% (2.55–10.07) | 17% (2.9–10.51) | 0.996 |

| Employed | 72.1% (64.12–79.18) | 66.7% (58.60–74.07) | 0.352 |

| Weight gain | 0.511 | ||

| Adequate | 66.5% (17.44–31.10) | 60.1% (11.65–23.57) | |

| Inadequate | 35.5% (7.65–18.30) | 39.9% (8.43–19.87) | |

| Physical activity | 78.2% (71.01–84.34) | 74.5% (67.16–80.43) | 0.504 |

| Vitamin supplement | 85.7% (79.34–90.69) | 89.5% (83.91–93.68) | 0.313 |

| Iron supplement | 61.2% (53.16–68.84) | 72.5% (65.07–79.17) | 0.037 |

| Previous pregnancy | 55.6% (46.32–62.34) | 58.8% (50.89–66.42) | 0.498 |

| Previous pregnancy loss | 30.6% (22.94–37.70) | 32.7% (25.59–40.40) | 0.683 |

While no significant difference was observed, the percentage of women who smoked during pregnancy was higher in those with inadequate fish intake.

Supplementation was higher among those with inadequate fish consumption during pregnancy. While no differences were observed for vitamin supplementation, statistically significant differences were observed in iron supplementation. There were a greater number of women with inappropriate consumption of fish in pregnancy who needed iron supplementation, 11.3% more than women with adequate intake of fish during pregnancy.

Along the line of iron supplementation, no significant differences were observed in anemia, although 14.9% of women with adequate fish intake suffered from prepartum anemia compared to a 20.8% of women with inadequate consumption of fish. For postpartum anemia, the prevalence was 6.4% of women with adequate fish intake and 11.3% of those who followed an inadequate diet in fish in pregnancy.

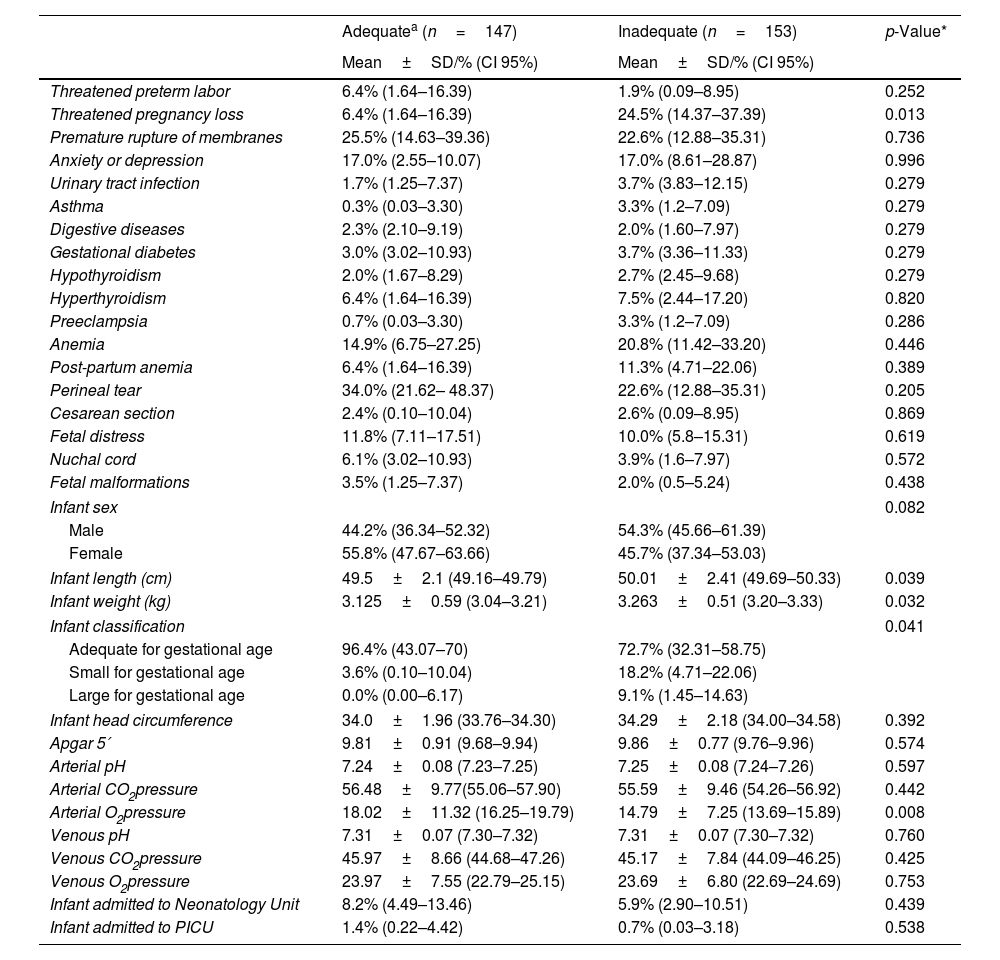

When it comes to other maternal clinical outcomes (Table 2), significant differences were observed for threatened pregnancy loss with women with inadequate fish consumption presenting a higher prevalence (24.5% versus 6.4%) but there were no significant differences for threatened preterm birth or premature rupture of membranes.

Clinical data of the mother and/or infant during pregnancy and childbirth in relation to weekly maternal fish intake.

| Adequatea (n=147) | Inadequate (n=153) | p-Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD/% (CI 95%) | Mean±SD/% (CI 95%) | ||

| Threatened preterm labor | 6.4% (1.64–16.39) | 1.9% (0.09–8.95) | 0.252 |

| Threatened pregnancy loss | 6.4% (1.64–16.39) | 24.5% (14.37–37.39) | 0.013 |

| Premature rupture of membranes | 25.5% (14.63–39.36) | 22.6% (12.88–35.31) | 0.736 |

| Anxiety or depression | 17.0% (2.55–10.07) | 17.0% (8.61–28.87) | 0.996 |

| Urinary tract infection | 1.7% (1.25–7.37) | 3.7% (3.83–12.15) | 0.279 |

| Asthma | 0.3% (0.03–3.30) | 3.3% (1.2–7.09) | 0.279 |

| Digestive diseases | 2.3% (2.10–9.19) | 2.0% (1.60–7.97) | 0.279 |

| Gestational diabetes | 3.0% (3.02–10.93) | 3.7% (3.36–11.33) | 0.279 |

| Hypothyroidism | 2.0% (1.67–8.29) | 2.7% (2.45–9.68) | 0.279 |

| Hyperthyroidism | 6.4% (1.64–16.39) | 7.5% (2.44–17.20) | 0.820 |

| Preeclampsia | 0.7% (0.03–3.30) | 3.3% (1.2–7.09) | 0.286 |

| Anemia | 14.9% (6.75–27.25) | 20.8% (11.42–33.20) | 0.446 |

| Post-partum anemia | 6.4% (1.64–16.39) | 11.3% (4.71–22.06) | 0.389 |

| Perineal tear | 34.0% (21.62– 48.37) | 22.6% (12.88–35.31) | 0.205 |

| Cesarean section | 2.4% (0.10–10.04) | 2.6% (0.09–8.95) | 0.869 |

| Fetal distress | 11.8% (7.11–17.51) | 10.0% (5.8–15.31) | 0.619 |

| Nuchal cord | 6.1% (3.02–10.93) | 3.9% (1.6–7.97) | 0.572 |

| Fetal malformations | 3.5% (1.25–7.37) | 2.0% (0.5–5.24) | 0.438 |

| Infant sex | 0.082 | ||

| Male | 44.2% (36.34–52.32) | 54.3% (45.66–61.39) | |

| Female | 55.8% (47.67–63.66) | 45.7% (37.34–53.03) | |

| Infant length (cm) | 49.5±2.1 (49.16–49.79) | 50.01±2.41 (49.69–50.33) | 0.039 |

| Infant weight (kg) | 3.125±0.59 (3.04–3.21) | 3.263±0.51 (3.20–3.33) | 0.032 |

| Infant classification | 0.041 | ||

| Adequate for gestational age | 96.4% (43.07–70) | 72.7% (32.31–58.75) | |

| Small for gestational age | 3.6% (0.10–10.04) | 18.2% (4.71–22.06) | |

| Large for gestational age | 0.0% (0.00–6.17) | 9.1% (1.45–14.63) | |

| Infant head circumference | 34.0±1.96 (33.76–34.30) | 34.29±2.18 (34.00–34.58) | 0.392 |

| Apgar 5′ | 9.81±0.91 (9.68–9.94) | 9.86±0.77 (9.76–9.96) | 0.574 |

| Arterial pH | 7.24±0.08 (7.23–7.25) | 7.25±0.08 (7.24–7.26) | 0.597 |

| Arterial CO2pressure | 56.48±9.77(55.06–57.90) | 55.59±9.46 (54.26–56.92) | 0.442 |

| Arterial O2pressure | 18.02±11.32 (16.25–19.79) | 14.79±7.25 (13.69–15.89) | 0.008 |

| Venous pH | 7.31±0.07 (7.30–7.32) | 7.31±0.07 (7.30–7.32) | 0.760 |

| Venous CO2pressure | 45.97±8.66 (44.68–47.26) | 45.17±7.84 (44.09–46.25) | 0.425 |

| Venous O2pressure | 23.97±7.55 (22.79–25.15) | 23.69±6.80 (22.69–24.69) | 0.753 |

| Infant admitted to Neonatology Unit | 8.2% (4.49–13.46) | 5.9% (2.90–10.51) | 0.439 |

| Infant admitted to PICU | 1.4% (0.22–4.42) | 0.7% (0.03–3.18) | 0.538 |

Statistically significant differences were observed for infant birth weight and length as well as newborn classification. Regarding the size of the baby, we found that women with inappropriate fish intake during pregnancy gave birth to children a little higher on average than children born to women with appropriate fish intake during pregnancy. On the other hand, it was appreciated that the weight of the newborn in women with adequate consumption of fish during pregnancy was lower than the weight of the newborn of women with inadequate consumption of fish during pregnancy. In the classification of the newborn, it can be seen that within the group of women with adequate fish intake during pregnancy, the vast majority (96.4%) gave birth to a baby adequate for gestational age (AGA), and only 3.6% presented a small child for gestational age (SGA) with no women giving birth to a large for gestational age (LGA) baby. Meanwhile, 72.7% of women with inadequate fish intake during pregnancy gave birth to AGA babies, 18.2% to SGA babies and 9.1% to LGA babies.

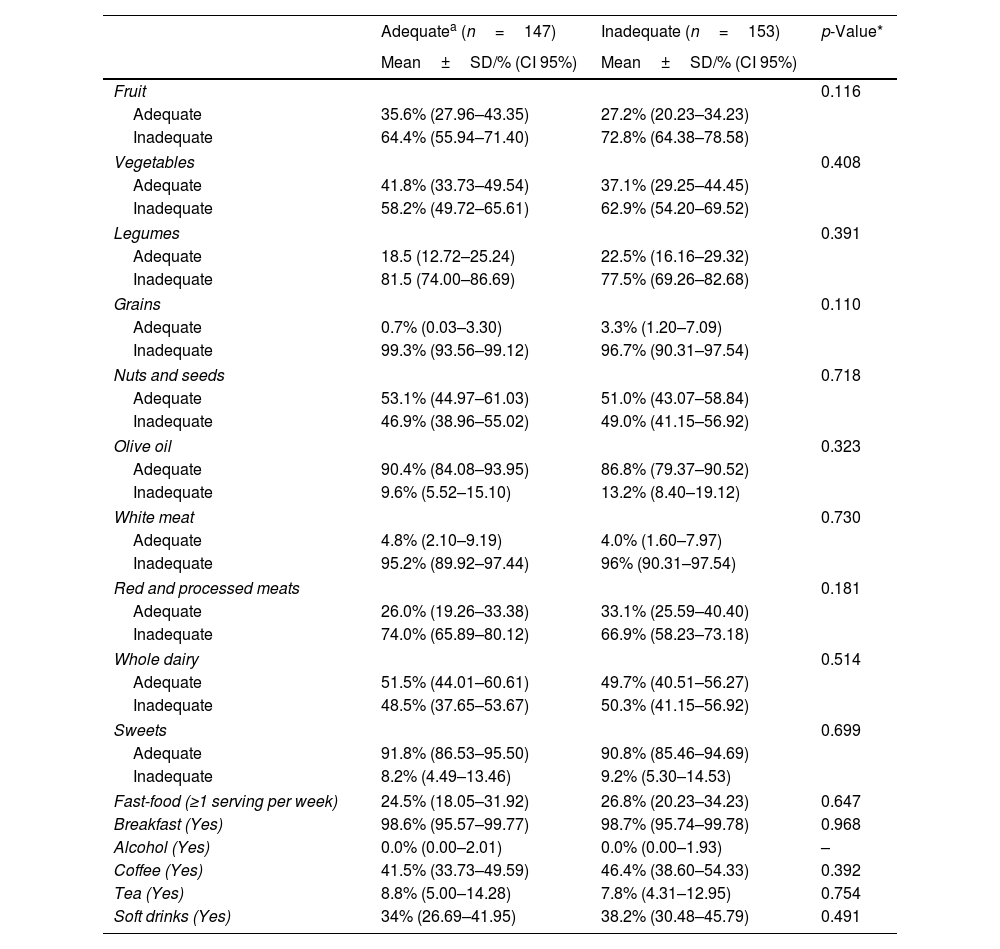

Table 3 shows the results corresponding to the adequacy of the mother's diet, comparing both groups with the adequate or inadequate intake of the various types of food, in order to verify which group followed a better eating pattern during the pregnancy. Women who took an adequate intake of fish during pregnancy generally had a healthier eating pattern, but no statistically significant differences were observed.

Maternal dietary pattern in relation to weekly maternal fish intake.

| Adequatea (n=147) | Inadequate (n=153) | p-Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD/% (CI 95%) | Mean±SD/% (CI 95%) | ||

| Fruit | 0.116 | ||

| Adequate | 35.6% (27.96–43.35) | 27.2% (20.23–34.23) | |

| Inadequate | 64.4% (55.94–71.40) | 72.8% (64.38–78.58) | |

| Vegetables | 0.408 | ||

| Adequate | 41.8% (33.73–49.54) | 37.1% (29.25–44.45) | |

| Inadequate | 58.2% (49.72–65.61) | 62.9% (54.20–69.52) | |

| Legumes | 0.391 | ||

| Adequate | 18.5 (12.72–25.24) | 22.5% (16.16–29.32) | |

| Inadequate | 81.5 (74.00–86.69) | 77.5% (69.26–82.68) | |

| Grains | 0.110 | ||

| Adequate | 0.7% (0.03–3.30) | 3.3% (1.20–7.09) | |

| Inadequate | 99.3% (93.56–99.12) | 96.7% (90.31–97.54) | |

| Nuts and seeds | 0.718 | ||

| Adequate | 53.1% (44.97–61.03) | 51.0% (43.07–58.84) | |

| Inadequate | 46.9% (38.96–55.02) | 49.0% (41.15–56.92) | |

| Olive oil | 0.323 | ||

| Adequate | 90.4% (84.08–93.95) | 86.8% (79.37–90.52) | |

| Inadequate | 9.6% (5.52–15.10) | 13.2% (8.40–19.12) | |

| White meat | 0.730 | ||

| Adequate | 4.8% (2.10–9.19) | 4.0% (1.60–7.97) | |

| Inadequate | 95.2% (89.92–97.44) | 96% (90.31–97.54) | |

| Red and processed meats | 0.181 | ||

| Adequate | 26.0% (19.26–33.38) | 33.1% (25.59–40.40) | |

| Inadequate | 74.0% (65.89–80.12) | 66.9% (58.23–73.18) | |

| Whole dairy | 0.514 | ||

| Adequate | 51.5% (44.01–60.61) | 49.7% (40.51–56.27) | |

| Inadequate | 48.5% (37.65–53.67) | 50.3% (41.15–56.92) | |

| Sweets | 0.699 | ||

| Adequate | 91.8% (86.53–95.50) | 90.8% (85.46–94.69) | |

| Inadequate | 8.2% (4.49–13.46) | 9.2% (5.30–14.53) | |

| Fast-food (≥1 serving per week) | 24.5% (18.05–31.92) | 26.8% (20.23–34.23) | 0.647 |

| Breakfast (Yes) | 98.6% (95.57–99.77) | 98.7% (95.74–99.78) | 0.968 |

| Alcohol (Yes) | 0.0% (0.00–2.01) | 0.0% (0.00–1.93) | – |

| Coffee (Yes) | 41.5% (33.73–49.59) | 46.4% (38.60–54.33) | 0.392 |

| Tea (Yes) | 8.8% (5.00–14.28) | 7.8% (4.31–12.95) | 0.754 |

| Soft drinks (Yes) | 34% (26.69–41.95) | 38.2% (30.48–45.79) | 0.491 |

In the present study, it was observed that women, regardless of fish consumption during pregnancy, presented inadequate fruit intakes. Women with adequate fish intake had an appropriate fruit intake (35.6%) 8.4 points higher than women with inadequate fish intake during pregnancy (27.2%). The same pattern can be observed for vegetable intake, with women presenting an overall inadequate intake and those with adequate fish intake presenting better vegetable consumption levels (41.8% versus 37.1%).

It was also noted that women with adequate intake of legumes were more numerous in the group of inappropriate fish consumption in pregnancy, 22.5%, compared to 18.5% of women with adequate intake of fish.

Women with inadequate fish intake in pregnancy had better results in terms of grain consumption, since they had a higher percentage (3.3%) than women who had adequate fish consumption in pregnancy (0.7%).

Of women with adequate intake of fish during pregnancy, 53.1% also presented an appropriate intake of nuts while 51.0% of women with inadequate intake of fish during pregnancy also presented an appropriate intake of nuts.

Olive oil intake adequacy in women with adequate consumption of fish in pregnancy was slightly higher (90.4%) than that of women with inappropriate consumption of fish in pregnancy (86.8%).

The intake of white meat is, after grains, the food group with the worst intake levels among all women. Only 4.8% of women with adequate fish intake and 4.0% of those with inadequate fish intake present adequate intakes. 26.0% of women with adequate fish consumption during pregnancy consumed red meat adequately compared to 33.1% of women with inadequate fish intake during pregnancy.

Of women with adequate intake of fish during pregnancy, 91.8%also presented an appropriate intake of sweets while 90.8% of women with inadequate intake of fish during pregnancy also presented an appropriate intake of sweets. Women with adequate fish consumption during pregnancy frequented fast-food establishments, at least once a week, less than women with inadequate fish consumption during pregnancy (24.5% versus 26.8%).

Regarding having breakfast daily and consuming alcohol during pregnancy, these two habits present the best results of all the dietary intakes studied. None of the women declared consuming alcohol and almost all (98.6% and 98.7%) reported having breakfast daily.

There was an important stimulant drink intake, whether coffee, tea or cola. In the case of coffee, 41.5% of women with adequate intake of fish in pregnancy and 46.4% of women with inadequate intake of fish in pregnancy consumed it. For tea intake, a slightly higher consumption was observed by women with adequate fish intake (8.8%) compared to 7.8% in the group of women with inadequate fish intake. With regard to cola, its consumption by women with inadequate fish intake was higher (38.2%) than in women with adequate fish intake (34%).

DiscussionAround half of the women studied presented an appropriate fish intake during pregnancy. This is noticeably higher than reported in a previous study by Mendez et al., 2009, carried out in Menorca (Spain) where only differences in fish consumption can be observed, since only 17.1% of pregnant women reported fish consumption>2 times/week.12 However, results from another study reported a median of fish intake of 4.45 times/week (3.45 IQR) for a Spanish cohort of pregnant women, which would be considered as adequate intake, the highest of the birth cohorts studied.13

The results regarding smoking during pregnancy are similar to those in the study by Gow et al., 2018,14 where it was found that lower fish consumption was associated with a 25% lower risk of smoking, whilst high fish consumption was associated with a 50% lower risk. The number of women who smoke during pregnancy remains higher than desired as its negative effects are numerous and well-known, including maternal respiratory infections, congenital malformations, greater probability of premature birth and even sudden death of the infant.

An explanation for why more women with inappropriate consumption of fish in pregnancy needed iron supplementation could be that fish are rich in heme iron, which is absorbed more efficiently, as it is more bioavailable, from the diet than non-heme iron.15 Women with adequate fish intake also consumed more fruits and vegetables and should therefore be able to also better absorb more non-heme iron thanks to vitamin C.15 From these results it can be extracted fish plays an important role in the prevention of anemia and that regular consumption of fish could optimize iron status during pregnancy.

The fact that anemia affects more women with inadequate intake of fish even though their rate of supplementation is higher may be due to the fact that their eating pattern is less healthy. Comparing the percentage of women with anemia with previous studies,16 it was observed that the proportion of women with anemia in this study was between the previously reported values.

When it comes to other maternal clinical outcomes, a study by Benjamin et al., 2019,17 found that there was no association between fish consumption and early preterm delivery<35 weeks. On the other hand, in a previous study the intake of 2 or more servings of fish decreased the risk of premature delivery, although it was also found that if intake was very high, the risk of premature delivery was increased due to methylmercury.18 Inadequate fish intake could be associated with the premature rupture of membranes through its role as a source of zinc, whose deficiency can generate the production of proteolytic enzymes involved in the rupture of membranes.

The results for infant birth weight and length as well as newborn classification suggest that adequate fish consumption during pregnancy favors the child's size being AGA. However, previous studies have found no association between fatty fish intake before or during pregnancy and size at birth.19 The same happens in the study of Taylor et al., 2016,20 where it was observed that there were no significant associations of birth weight, head circumference or crown-heel length in fish-eaters or non-fish-eaters, with the exception of a negative association with birth weight in the adjusted model for non-fish-eaters.

The results obtained for fruit and vegetable intake are quite low since fruits and vegetables are nutrient-dense foods that support health and are essential for the prevention of chronic diseases such as diabetes, cancer, or heart disease among others. In the perinatal period, adequate consumption of vegetables and fruits has been previously associated with increased birth weight as well as lower odds of pre-eclampsia and gestational diabetes.21–23

The results for adequate intake of legumes are low. It is known that legumes provide very important nutrients for pregnancy, especially folate and fiber, with a stimulating function of intestinal motility, which decreases due to the action of progesterone.24 According to the results, the consumption of legumes was higher in women with inadequate intake of fish during pregnancy, which is contradictory, since they generally have worse eating habits than those of the group of women with adequate consumption of fish during pregnancy. This could be that they are replacing one protein source (fish) for another (legumes).

Grains is the food group with the worst levels of intake adequacy and warrants special attention in terms of possible nutritional interventions to improve maternal nutritional status. In this case, the problem is the excessive intake of grains and given the results for other food groups presented previously, it would be recommendable to replace some of the servings of grains consumed with these under consumed foods.

Nut fat contributes to cardio protection and cholesterol regulation, and its folic acid content is very helpful in the pregnant population.25

As expected for a Spanish population, daily consumption of olive oil in women during pregnancy was quite high. These results are very positive since supplementation with extra virgin olive oil has been studied in pregnant women and benefits have always been seen, such as the lower risk of the newborn being born SGA or LGA, emergency cesarean section or UTI in the mother.26

The intake of white meat is, after grains, the food group with the worst intake levels among all women. Regarding the consumption of red meat, comparing our results with those of Haugen et al., 2008, we see that fewer women in this study consumed red meat improperly.18 This excess of red and processed meats is a significant problem, since its high consumption promotes the onset of cancer27 and has been associated with the risk of developing gestational diabetes28 and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.29

Most women presented appropriate intakes of sweets but around a quarter of women frequented fast-food establishments at least once a week. A previous study established a relationship between the intake of fast-food type with the appearance of gestational diabetes,28 especially the consumption of pizzas, sausages, and hamburgers, since they are high in poor quality saturated fat and trans fatty acids. These unhealthy fats suppress glycosyltransferase, which causes weight gain, oxidative stress and increased blood glucose.30

It appears that women are aware of the risks associated with alcohol use during pregnancy and eliminate it completely from their diet. The effects of skipping breakfast may be less publicized and perhaps not the main reason why women eat breakfast daily, but either way, the results observed for this habit are very positive.

Coffee, tea or cola drinks are considered stimulants due to the caffeine they contain that produces effects such as stimulation of the central nervous system and decreased drowsiness, although if consumed in excess there is a risk of cardiovascular problems in women and delayed fetal growth.31 In a study carried out in Japan, it was observed that prenatal caffeine levels were associated with a higher probability of SGA children being born, however, the confidence in the causality of association was moderate and more studies will be needed.32

Strengths and limitationsAs with any scientific study, there are some strengths and limitations to consider. One of the main strengths of this study is that the participating women represent a homogeneous population without any identified selection bias and covered by the public universal health care existing in the region regardless of socioeconomic factors, increasing the internal validity of the study and strengthening the results. When it comes to the limitations or weaknesses of this study, first, the sample size may not be ample enough to detect statistically significant differences among the two groups especially since in this case women were split almost equally in the adequate and inadequate fish intake categories which may hide differences. Another limitation which could have also influenced the distribution of the women into the two groups is the lack of a strict recommendation for fish intake in pregnant Spanish women. While other countries do have these recommendations, dietary intake recommendations must take into account socio-cultural elements and may not be adequate to transport to other countries. Finally, the lack of information on the type of fish consumed could also present a limitation since the available recommendations do differentiate between different species and even the cooking method, mainly due to their fat and possible mercury content. In future studies, the data collection should include more detailed inquiries on type of fish and method of preparation.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, fish intake during pregnancy is considered adequate for about half of the women studied. It is observed that those who had adequate fish intake during pregnancy followed an overall healthier eating pattern but no statistically significant differences for specific components were found. No specific negative maternal or fetal outcomes can be identified apart from the difference observed in infant weight for gestational age with infant of women with adequate fish intakes during pregnancy presenting better results. Therefore, overall fish intake in the population studied appears to be within a safe range but pregnant women should still be counseled on safe fish consumption during pregnancy in order to optimize infant birth weight and deter possible later detected effects derived from mercury toxicity.

Ethical considerationsThis study has been carried out in accordance with the World Medical Association Code of Ethics (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments on human beings; Uniform requirements for manuscripts sent to biomedical journals. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe (CEIC 2014/0116). All participants gave their informed consent, which included a confidentiality agreement according to Organic Law 15/1999, of December 13, on the Protection of Official Data.

FinancingThis research has not received specific support from public sector agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit entities.

Conflict of interestsNone.