Diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) is a chronic complication of diabetes mellitus. It is reported that diabetes is associated with a two to four-fold increase in the incidence of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) compared to non-diabetic subjects. Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) may play a role in the etiology of foot ulceration in patients with diabetes mellitus.

ObjectiveTo determine the association between peripheral arterial disease and diabetic foot ulcers in patients with type II diabetes mellitus.

MethodsA cross-sectional study was carried out at Hospital Belen of Trujillo, which all patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus ≥50 years were included. Presence or absence of both variables was measured in our study.

ResultsThree hundred twenty-two patients were included in the study. We found that 129 patients had peripheral arterial disease and diabetic foot ulcers (OR 3, 95% IC 1.087–8.242 and p<0.001).

ConclusionsIn this study, peripheral arterial disease was associated with diabetic foot ulcer in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) is a chronic complication of diabetes mellitus (DM) of great importance from medical and social aspects, since it has significant effects on the patient's quality of life and is related to higher healthcare costs.1,2 Prevalence of diabetic foot ulcer ranges from 4 to 10% in hospitalized patients.3–5 It is also a disabling complication, being the leading cause of non-traumatic amputations worldwide. The Global Lower Extremity Amputation Study Group estimated that between 14 and 24% of DFU patients require amputation.3,4,6

Recent studies suggest that risk of diabetic patients developing a foot ulcer is approximately 25% throughout their lives.6–9 DFU risk factors include: male sex, diabetes more than ten years, peripheral neuropathy, abnormal foot structure (bone alterations, calluses, nails thickening), peripheral arterial disease, smoking, history of ulcers or amputation and inadequate glycemic control.7–10 The reasons for rise in incidence of these disorders in DM involves the interaction of pathogenic processes like abnormal biomechanics of the foot, peripheral arterial disease, poor wound healing. Peripheral sensitive neuropathy disrupts normal protection mechanisms, allowing patients to suffer severe trauma or repeated mild ones, which often unnoticed. Proprioceptive sensory disorders cause abnormal weight support while walking, which results in the formation of calluses or ulcers. Motor and sensory neuropathy lead to an abnormal mechanics of the foot muscles and structural alterations (hammer toe, claw foot, prominence in the metatarsal, Charcot foot). Vegetative neuropathy (autonomic) causes anhidrosis and alters superficial blood flow of foot, which promote skin drying and fissure formation. Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) and poor wound healing impede resolution of small wounds of skin, allowing these to increase in size and become infected.9–12

PAD is defined as clinical disorder where there is stenosis or occlusion of lower limbs arteries. Atherosclerosis is the main cause of PAD in people over 40.13,14 The risk of atherosclerosis increases notably in diabetics, and epidemiological studies have confirmed a link between diabetes and rise in PAD prevalence.15–17 Diabetes is associated with a two to fourfold increase in PAD incidence compared to non-diabetic individuals. Among adult population ≥40 years of age, PAD prevalence is 9.5% in diabetic subjects, twice as much as the 4.5% prevalence in non-diabetics.18–21 In consequence, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends through consensus that the ankle-brachial index (ABI) should be performed as a measure of detection in all diabetic individuals >50 years of age or those who have suffered from the disease for more than ten years.10,12,21

PAD is an important predictor of ulceration of the foot in diabetic patients. Therefore, the physician who examines a patient with diabetes and foot ulcer should always assess the vascular status of lower limbs and specifically search for signs of ischemia, since up to 50% of these patients have PAD. Nevertheless, PAD detection and the assessment of its severity is a clinical challenge in diabetic patients with foot disease, due to altered clinical presentation of PAD and limitations of the diagnostic procedures. Moreover, the healing of the wound in these patients is influenced not only by presence of PAD but also by factors like infection and presence of comorbidities.22–24

DFUs are frequent complication in patients with diabetes mellitus, which have significant effects on their quality of life and involve greater costs in health care. However, when examining a patient with a diabetic foot ulcer, a proper evaluation of the vascular status of said limb is not performed. Due to this significant problem, the present study intends to measure the link between peripheral arterial disease and diabetic foot ulcers.

Material and methodsWe included patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus, who were older than 50 years of age and who were treated at the Hospital III-1 Belén de Trujillo throughout 2015. Patients were selected from the patients regularly controlled in the Program of Diabetes Control who showed good adherence to the treatment; those who had partial or total lower limb amputation were excluded. The sample was selected randomly. The variable, diabetic foot ulcer, was defined by the solution of skin continuity in any region below the ankle of any depth level with or without complications in people affected with diabetes. It also included gangrene and necrosis.12,25 Peripheral arterial disease was defined by an ankle-brachial index less than or equal to 0.91, using a portable vascular Doppler device. The ankle-brachial index is obtained by measuring the systolic blood pressure of both brachial arteries and both posterior tibial arteries using a portable vascular Doppler device. Brachial pressure is measured in both arms, and the highest pressure is used for the calculation of ABI; Ankle pressure of the posterior tibial artery is determined on each foot, and subsequently, the greater of these two measurements are used for the calculation of ABI. The index is obtained from the division of both arterial pressures.10,12,26

The sample size was calculated for a confidence level of 95% and an accuracy of 0.05, then corrected for finite population, thus obtaining a sample size of 322 elements. The research was done with a transversal analytical model to measure the association between both variables.

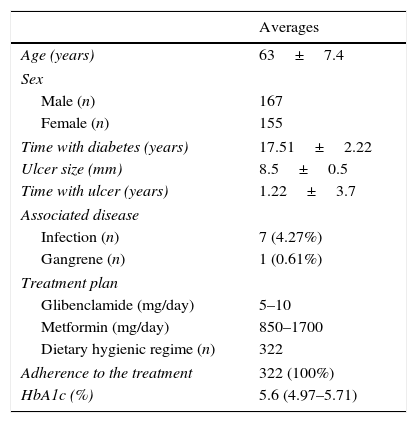

ResultsData presented in this study determined PAD and its association with DFU in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. The characteristics of the studied patients are shown in Table 1.

Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Characteristics of the study sample.

| Averages | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63±7.4 |

| Sex | |

| Male (n) | 167 |

| Female (n) | 155 |

| Time with diabetes (years) | 17.51±2.22 |

| Ulcer size (mm) | 8.5±0.5 |

| Time with ulcer (years) | 1.22±3.7 |

| Associated disease | |

| Infection (n) | 7 (4.27%) |

| Gangrene (n) | 1 (0.61%) |

| Treatment plan | |

| Glibenclamide (mg/day) | 5–10 |

| Metformin (mg/day) | 850–1700 |

| Dietary hygienic regime (n) | 322 |

| Adherence to the treatment | 322 (100%) |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.6 (4.97–5.71) |

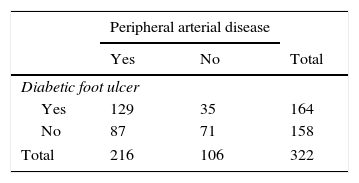

Obtained results show frequencies found with their respective percentages in a contingency chart for PAD and DFU variables; the association between both variables was measured using chi square with a significance of 95% and the respective calculation of the odds ratio as shown in Table 2.

DiscussionThe importance of this study lies mainly in the fact that both DFU and PAD affect the quality of life, generating disability in the diabetic patient. Although it is true that using a cross-sectional design places us on the border between descriptive and analytical works, like non-experimental descriptive comparative study, we have applied the rigidity of the model to place it at the level of evidence III according to the US Agency for Health Care Policy Research,27 which is considered in the Degree of recommendation B.

The rigidity used in the selection of the sample allows us to correctly infer results we obtained. We must also remember that a cross sectional study only evaluates hypotheses of a simple association, but allows hypotheses of explanation and even of causality. In our case, we can only affirm that we have verified that there is an association between PAD and DFU (OR 3, 95% IC 1.087–8.242 and p<0.001).

In the present study, we found that 78% of patients with DFU also had PAD. A study of 1229 type II diabetic patients in the Netherlands found that only 49% of patients with DFU had PAD. This difference may due to EAP or a higher prevalence of smoking or neuropathies in diabetics, variables that are also associated with DFU,28 in addition to the level of health education in patients from developed countries. In a Latin population similar to ours, a study of 60 diabetic patients performed in Mexico,29 65% of patients with DFU had PAD, a result closer to us. Although the difference with us may be due to the case control, which only had 20 cases of DFU, while 40 controls had no DFU.

Other studies verify the relationship between the variables we are studying. In a case-control study, peripheral vascular disease is a risk factor for foot ulcers (OR: 10.6, CI: 1.8–5.55.6), even this study had a sample not suitable in comparison to us. In a prospective study, we found an RR: 3.1, which indicates a relationship between both variables, the similarity in the results of our study is the inclusion of subjects according to the International Federation for DFU.30,31

ConclusionPeripheral arterial disease is one of the factors linked to diabetic foot ulcers in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, which stresses the importance of early treatment of this vascular disease. Multivariate studies are recommended in order to research its participation in the genesis of the ulcer.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FundingFinanced through the resources of the authors.

Conflict of interestNone.