Objective: The term grief, from the French term grever, which means “to burden, to oppress”, can be defined as the process through which a person must go due to the loss of a loved one. We present a case of grief elaboration in a patient and his family that face a terminal illness.

Clinical case: The patient is a 51-year-old man diagnosed with stage T4a N2b M1 colon adeno-carcinoma. He came to the Department of Psycho-Oncology presenting depressive symptoms, marital and family issues associated with a medical condition, and work related issues.

Conclusions: The patient was diagnosed with a secondary major depressive disorder episode in reaction to his medical condition. He was prescribed anti-depressive treatment, and family psychotherapy was recommended for grief elaboration.

Introduction

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (4th edition revised text) classifies grief as one of the problems that may be the object of clinical attention; it may be utilized when there is a reaction to the death of a loved one.1 As part of the reaction to the loss, some individuals present characteristic symptoms of an episode of major depression.

The duration and expression of normal grief vary considerably among different cultural groups. A major depressive disorder (MDD) diagnosis is made when the symptoms are still present 2 months after the loss. The presence of certain symptoms which are not characteristic in the reaction to normal grief may differentiate grief from an MDD episode. These symptoms include: a) guilt over things (rather than actions) done or not done at the time of the loved one’s death; b) suicidal thoughts more than the will to live; c) a morbid preoccupation with a sense of being worthless; d) psychomotor retardation; e) prolonged functional impairment; and f) hallucinations other than “visions” in which the person briefly hears or sees the deceased.1

Withdrawal into oneself (or social withdrawal) is when the person gives the impression of living in a parallel world where it is hard to communicate with him/her. It is inaccessible to our language and reasoning. Depression is the most frequent cause of withdrawal.

During the last few days or weeks we are able to see a decrease in the speed in thinking processes and in motor activity, accompanied by a state of dejection frequently attributed to physical fatigue.2

The introduction of a functional biopsychosocial model (which simultaneously includes biological, psychological, social and functional aspects) allows us to comprehend and evaluate the different factors that interact with the subject’s response and his/her perspective of death.2

A severe and prolonged disease transforms and affects the lives of the people living with the sick person.2 Concerns about future consequences, loneliness, the household’s economy, the children’s education, etc., establish a group of emotions intense enough to explain most of the observed reactions in the families of terminal patients.3 Family interventions must be flexible enough to satisfy the patient’s and the family’s spectrum of needs, and specific enough to approach and manage the identified problems. The general purpose is to reach the best solution for the family among the complex and conflictive requirements.4,5

Proper communication with the patient during the initial oncology diagnostic interview may be the best therapeutic tool. The ability to know when and how to explain diagnosis and treatment, and the ability to make sure the person understands and commits to his/her disease are key steps in order to reach clinical success.

Communication requires proper space and time, making quantity and quality of time devoted to the patient essential. Within the communication objectives in the initial oncology diagnostic interview there are: to humanize assistance with special stress in the oncologic patients; to tune transmitters and receptors so that messages can be decoded and shared; to transmit hope, safety and protection; to clarify information, doubts, feelings and emotions; to facilitate therapeutic relationships; and to strengthen doctor-patient relationships.

Communication is 90% non-verbal. The patient analyzes and interprets gestures, glances, and even silences. The doctor communicates information as well as feelings.

The empathic response “I understand what is happening”, “I understand that you are not well” shows our attention and solidarity.

How can we find facilitators in diagnostic communication? It is important to convey the idea of “I have time to listen”, maintain eye contact, smile, be relaxed, not to be in a hurry and show concern for the problem(s) affecting the patient (empathy).

How to react to the expression of intimate feelings? If the patient begins to cry, people must not try to stop him/her as if it were a hemorrhage, we must prepare for catharsis (expression of deep painful feelings). Our initial reaction should be to remain silent, thus allowing the patient to live through his/her emotions, followed by looking at the patient’s face in a continuous way.

Empathy is the backbone of clinical practice (it relies on an effort to make someone else’s reality ours, a person who, up to this point, we did not consider to be a relative or a friend). It is understanding the patient’s position in an aid relationship. It begins when we listen to someone without assuming anything and are willing to help him/her. It is the effort to recognize the counterpart as another emotional being.

Family support allows us to predict the patient’s adaptation to cancer and its treatment. Treatment acceptance and its complications by the patient depend on the attitude taken by the people close to him/her.

Health professionals need to spend some time (which is not totally contemplated) for family participation as an ally in patient care. The family can facilitate or block efforts made by the patient to adapt and withstand the disease.

We present the case of a patient with a colon cancer diagnosis with a poor prognosis presenting major depression symptoms and family and personal conflicts.

Clinical case

The patient is a 51-year-old man, married, catholic, civil engineer who was referred to us by the oncology service presenting depressive symptoms, marital and filial problems secondary to a colon adenocarcinoma diagnosed in May 2011. The patient was operated on, and later received palliative chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The tumor was classified as a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma extended to the mesocolon and with an angiolymphatic invasion, stage T4aN2bM1, with a poor short-term prognosis.

He came to the psycho-oncology department presenting changes in his behavior, irritability, verbal aggression towards his children, and low tolerance to everyday problems worsened by the physical pain caused by chemotherapy. In addition, he refers to feeling sadness, guilt, anhedonia, a sense of worthlessness, anguish, suicidal thoughts, dyspnea, intermediate insomnia and hyporexia. These symptoms have increased secondary to his physical deterioration. He also presents family conflicts associated with his medical condition, poor communication and difficulty expressing affection in the family.

During physical examination, we found him to be conscious, oriented, cooperative, irritable (mood accordingly), containing feelings of remorse and sadness (cried easily). He had, anhedonia, logical, organized thoughts, a sense of worthlessness, normal language and attention and preserved concentration, memory and judgment. He complained of hyporexia, intermediate insomnia and a decreased libido. He denied having sensory-perception alterations. He referred to having suicidal thoughts, denied any suicide attempts or plans, and self and/or hetero-aggressiveness.

Family evaluation

It is a two-parent nuclear family, with well-defined limits. We observed good communication among the marital system and parent/child conflicts, with difficulty showing affection, a father in a peripheral role, and a tendency to minimize and deny problems.

We suggested family psychotherapy in the Gesell chamber to cope with grief, improve communication and expression of affection, working with two therapists for 9 sessions. The Gesell chamber is a room designed to allow human observation. It consists of two rooms separated by a one-way mirror, thus enabling us to see and listen to what’s happening in one of the rooms, but not the other way around.

Using this system, they performed short, specific and structured therapeutic activities, in 60-minute family psychotherapy sessions, conducted from a theoretical perspective, with a specific purpose and an intervention structure by the family psychotherapy supervising team.

In the first session we were introduced to the family members. The father, 52 years old who is the identified patient; the mother, a 46-year-old stay at home mom, and their three children; two sons ages 23 and 16 and a daughter 21 years old, who are all students.

We obtained information about their family background and family dynamics in order to identify potential problems. We focused on exploring the father’s purpose of consultation, and we observed that the family had little information about his state and prognosis.

We identified father-daughter communication problems (she remained silent for most of the session, looking at her cell phone, and when we asked her the reason for her behavior, she replied: “I don’t have much to say, I barely talk to him”).

We also observed demands of affection by the rest of the children, because of the father’s peripheral role due to his workload.

Mother: “Communication between my children and their father has been difficult, they spend most of their time at school and doing sports and then my husband comes home late from work.”

Younger son: “I talk to my mom a lot, but not with my dad, he’s always at work, and lately he arrives home and gets upset about everything.”

When we questioned the relationship between the daughter and her dad, she commented in a blunt and annoyed way “I do see him at night when he gets home, but we don’t talk. He is very serious and does not hug us, I think that’s the reason I am like this with him. I don’t know my dad.”

Mother: “I tell my children to reach out to their dad, he is devoted to his work, but lately he has been very irritable because of the chemotherapy, and the kids prefer to be outside all day long to avoid arguing with him.”

The oldest son did not attend the first appointment because of work-related commitments.

In general, we observed a good relationship among the marital system as well as a good relationship between the mother and the filial system.

We suggested specific cohabitation tasks (i.e. going out to eat together) to improve communication and increase quality time among them.

All family members were present on the second session, they took their places, and we asked them to change places so that the patient sits among his children. We began by welcoming the oldest son who because of work-related commitments did not attend the previous session, he began by introducing himself, we asked him whether or not he knew why we were all gathered, to which he responded: “I know it’s because of my dad’s disease”. He seemed anguished; avoiding talking about the disease, was nervous and displayed difficulty in expressing himself.

The older son talked about his relationship with his father: “He has always been a role model, a hard worker; currently we are not spending much time together because of our schedules.”

Daughter: “My brother is never home, he is always exercising, at work, out with friends, he is never with the family.”

We reviewed the previous session’s homework, and asked them if they had done it or not, the mother replied: “We tried, but because of our everyday activities it was hard for us to get together. When at home, we tried to eat together; my daughter and my younger son were more in touch with their dad.”

Daughter: “Yes, I tried being closer to him, but I sometimes think that I am unable to do so. It upsets me that he is always in a bad mood, it bothers me that he yells at my mom, she tries doing things for him, and he gets upset about everything, sometimes I don’t know how to approach him.”

Father: “After the chemotherapies I feel really sick, now I have opted to not talk to my family so I don’t get upset, the noise bothers me a lot, and I do not tolerate things so easily.”

We suggested other activities so that both subsystems cohabitate, we asked the daughter to propose an activity to perform with her father and she replied: “I can’t think of anything.”

The father suggested going out for coffee with his daughter and going to the movies with the entire family.

During this session the daughter seemed less angry at her father. She came to terms with the fact that her dad’s irritability is caused by the physical discomfort and she agreed to be more patient with him.

In the third session the daughter talked about the chat she had with her father, she seemed to be more affective “I have realized we are very much alike, that’s why it was common for us to have conflicts. It is very difficult for me to express to him what I feel. That’s probably where we are alike the most. It is not easy for me to approach you dad, because of your character and mine, but I want to tell you I love you very much and that you are the most important thing for me.”

Father: “My daughter you know I adore you, I know it has been difficult for me to be close to you because of my work, but all of you are more important. I know I am not an affectionate father, but now that I have this disease I have come to realize that I need you more than ever, and I do admit that I get desperate because of the chemotherapy, but I’m doing the best I can.”

In the following sessions we approached the subject of cancer, and the prognosis of the disease, trying to favor the acceptance of loss.

Therapist: “Do you know what the current state of your disease is?

The patient talked openly about it, “I know it’s a terminal disease, I know the prognosis, and every time after the chemotherapy I feel worse. I have been very happy I have had the chance to spend time with, talk to, and be close to my children, but I know one day I won’t be here.”

Youngest son: “I love my dad very much, and I don’t want anything to happen to him, we are doing our best, we have always succeeded and now we will too.”

Mother: “We put our faith in God and the doctors that my husband will get better.”

We observed the different stages of grief in the family members according to the Kubler-Ross model.6 The youngest son remained in denial and anger during most of the sessions. The rest of the family was in a stage of bargaining and depression.

We tried approaching the subject of the patient’s disease, they mentioned they don’t yet know the post-chemotherapy results; they seem optimistic due to the patient’s stability.

We ask them if they had considered negative results. The youngest son who seems irritable says: “I’m sure my dad is going to be healthy.”

Mother; “I trust in God, he will help my husband and my children get by.”

The patient speaks about the possibility of the cancer not going away, “I feel fine now, but with this disease I do not know what will happen tomorrow, I trust things will have a positive outcome but I also know cancer is a terminal disease,”

Daughter: “I wish the results are positive, but if that wasn’t the case, I will be by my dad’s side fighting together, and I will support him on everything, I love you and I want everything to be ok.”

Oldest son: “I know my dad is a very strong man, and that we are all here to support him, I would prefer to wait and see the results.”

The fifth session was canceled because new studies were performed on the patient and the results were not good, tumor activity continued, and chemotherapy cycles were restarted.

We assessed the family’s needs and difficulties, mainly finding problems expressing verbal affection. We helped the emotional relief through direct questions and answers about feelings and thoughts, trying to prevent feelings of guilt and normalizing feelings and thoughts.

In the sixth session at first we deviated from the main topic, denying the fact that the patient is deteriorating every day, on this occasion the patient spoke slower, making pauses and breathing heavily. They talked about the children’s weekly activities, football games and the youngest son’s bad behavior. The daughter seemed sad and thoughtful. She limited herself to answering the questions.

They continued talking about the children’s multiple activities for part of the session; they mentioned that the last time they were not able to be there because of the patient’s work.

Patient: “The pain is more and more intense”. Therapist: “Do you know the current state of your disease?” and they mention that he will continue with the chemotherapy. “Have they informed you about the prognosis of your disease?”

Patient: “It is uncertain, but I feel very tired of it all, I have physical discomfort, I know that sooner or later I may go, I have put all my effort into this, yet we know it is a progressive disease, and I feel weaker, it makes me feel bad that they do not want to talk about the fact that I feel worse and worse and I feel the end is near.”

When we interrogated the family about the feelings about what the patient just said the first one to talk was the daughter who said: “I know you feel sick, I’ve witnessed all the efforts you have made, I am expecting the best outcome from the treatment, but I do know the pain you feel is very strong, we have to wait and support you dad.”

Mother: “The truth is that we’ve always looked forward. He and I decided to fight together when they gave him the diagnosis so we are not considering the option of his death, honestly we haven’t thought about that.”

The youngest son got anxious and began to cry, “My dad is going to be fine, he has fought and it will be like that until he is not sick anymore.”

Therapist: “However the patient was telling us that every time that his pain was more intense, he is suffering and tired, we do expect the treatment to be successful, but what would happen if it doesn’t turn out like that, what would happen if he died?

Wife: No, he is making the effort and we all support him. That option hasn’t been considered, we have been focusing on in the fact that we will get through this, as we have before.

Daughter: “I have thought about the possibility, as I see him, I wouldn’t want that to happen, but if it did, I would feel calm because I had the chance to tell him I love him very much, and I would know that he did his best to beat the disease.” She begins crying and tells him: “I don’t want you to die dad.” We ask the patient to please hug and kiss his daughter.

The youngest son, crying and anxious, says: “He is going to be fine; my dad is not going to die because we haven’t even considered it, he will come through like he has before.”

Oldest son in a very thoughtful manner says: “First, we have to wait for the results of the new studies after this chemo. We hope everything will be fine.”

The therapist asks the patient: “Is there anything you would like to tell or ask your family right now?”

Patient: “I would like to tell them I love them very much, that they are wonderful children, and to my wife that she is my partner. That she has always been there for me, that thanks to her we were able to provide for our children, and that she will continue guiding them because she is a wonderful woman, and I love all of you.”

We identified and potentiated family resources, the collaboration in house chores and organization in moments of crisis, as well as the ability to care for a loved one.

Lastly, we elaborated a care plan, establishing performance standards and preventing the risk of family claudication, principally the psychoeducation of the physical symptoms of cancer3 and the way they affect the father’s emotional state, facilitating the participation in family activities that the patient may be able to perform (i.e. eating in bed accompanied by his children). In addition, we promoted reconciliation between the father and the filial system, and we favored the parting of a loved one in an affectionate manner.

Discussion

The death of a loved one is considered to be the most distressing vital event that a human being can face. Some studies concluded that people who are grieving have a higher morbimortality than most of the general population.3 It has been proven that after a major loss, two thirds of the people grieving evolve normally, while the rest suffer from alterations, to either physical or mental health, or both.3,5

Grief can increase the risk of suffering psychosomatic disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and suicide. In addition, a quarter of widowers (male and female) suffer depression or anxiety in the first year after the loss. Other authors note that a third of primary consultations have psychological origins, and that out of this group a quarter is identified as a result of some sort of loss.3

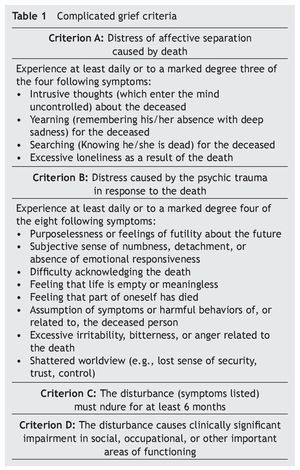

There is no diagnostic consensus regarding “complicated grief”, therefore it is not included in the DSM-IV-TR classification. However, within the additional problems that may be the object of clinical attention, there are six symptoms which are not characteristic of a “normal” grief reaction and may be useful differentiating this from a major depressive episode.1 In 1999, Prigerson et al7 developed the first criteria of complicated grief. These criteria have been used to diagnose complicated grief (table 1).

The results of the investigations performed on the efficacy of the treatments indicate the usefulness of therapeutic intervention in the prevention of “high risk” grievers, in complicated grief and other disorders related to loss.3,8

We could talk about the different levels of attention, such as: a) accompanying (level 1) performed mainly by trained volunteers; b) counselling (level 2) performed by health professionals (doctors, psychologist, nurses, social worker); and c) specialized intervention (level 3) in grief aimed at “high risk” grievers, complicated grief and grief-related disorders, performed by specialized health professionals (psychologists and psychiatrists).3

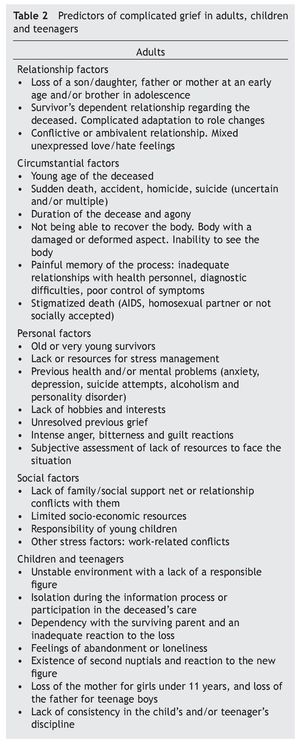

According to the literature1-12, the case’s prognosis variables that may evolve from a normal grief to a pathological grief are: presence of ambivalence in the pre-existing relationship with the father; the presence of previous grieving within the family (the death of a close aunt months prior to the beginning of the cancer treatment); the evolution of the terminal disease; guilt which allows thoughts to fixate on past events, thus making the possibility of thinking and planning difficult; the loss of the father in teenage boys; a dependent relationship between the family members who survive the disease and a complicated adaptation to role changing (table 2). These variables were the predictors we took into consideration in this clinical case in order to begin psychotherapeutic treatment.

Grief was faced optimizing the family’s resources; we facilitated a space where they were able to express cognitions and emotions, grief manifestations were normalized, we broke isolation, which has been considered an initial response in previously healthy teenagers, we detected intense emotional reactions with depressive and anxiety symptoms, as well as sleep, cognitive and behavioral disorders, associated with the deterioration in conduct and academic functioning of the youngest son, also interpersonal relationship difficulties, in the shape of anger towards the father from the daughter.

Denial was one of the stages frequently found, which may have made the normal evolution of grief more difficult.6

Grief in a teenager could also easily take a pathological course, conditioned by intra-psychic factors already existent at the moment of the loss.9,10

Research findings concur in highlighting the importance of support to the surviving parents and treatment of their emotional problems, given the fact that a number of studies have linked the functioning of these to the initial response, persistent alteration and even possible long-term effects on the children’s childhood, adolescence and early adulthood.11,12

In this particular case, it was necessary for the family to recreate the history of their relationship that they had with their father so they could stress the family’s good qualities and unidealize the father figure, so these resources continue in the survivors and can be used to restitute life with a different sense.

In the third week after the passing of the father we contacted the family over the phone. We considered it appropriate to schedule an appointment where the team got together with the family. The objective was to express our condolences, reinforce their roles as caregivers, facilitate the expression of emotions, feelings and thoughts, clear doubts, offer basic support, demonstrate our availability and assess if the main caregiver or any others required specific support.

The last session was with the spouse where we approached the activities performed by the family system after the loss. She described that she and her children took a trip where the family bonds were strengthened as well as the acceptance of loss. Finally, she talked about the reincorporation to work and school of each of the family members.

This case shows the importance of the identification and treatment of complicated grief to prevent the risk of suffering a future psychopathology or mental disorder.

Received: October 2013;

Accepted: February 2014

*Corresponding author:

Departamento de Psiquiatría,

Hospital Universitario “Dr. José Eleuterio González”,

Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León,

Ave. Madero y Gonzalitos s/n, Monterrey,

Nuevo León, 64460, México.

E-mail address:cariluna82@hotmail.com (C.E. Ramírez Luna).