This work gives a synopsis of the evolution of public administration control mechanisms in Mexico. It highlights the instrumental nature of oversight, as well as regulatory and assessment aspects, and discusses issues like the historical design of the control instruments used in Mexican public administration. Certain social and political aspects from a legal perspective of administrative anti-corruption regulations are then underscored. The article concludes by drawing attention to the fact that neither the newly designed political-administrative anti-corruption structure in Mexico (the National Anti-Corruption Commission) nor the new mechanism to emerge from draft legislation (the National Anti-Corruption and Oversight Institute) will not eliminate corruption in the country because they replicate the same model established for reforming legal institutions. This article aims to show how the Mexican model has repeatedly designed administrative rules and structures that are unable to rise above the political and social spheres in which the complex phenomenon of corruption is deeply entrenched and creates a schism between legislative development and Mexico's social-political experiences in its fight against corruption. These observations can serve to help other countries design anti-corruption instruments. China is cited in this article because this article was presented as a speech regarding the Mexican experience in that country. It should be noted that the intention of this study was not to make a comparison of corruption or of the legal structures in these countries, but to analyze the case of Mexico.

En el presente trabajo se aborda de manera sintética la evolución del control de la administración pública en México. Se destaca el carácter instrumental de control, su carácter normativo y valorativo. Además se abordan cuestiones como el diseño histórico de las herramientas de control de la administración pública mexicana; el enfoque legal de la norma administrativa contra la corrupción, se destacan algunos aspectos sociales y políticos, para concluir destacando que el nuevo diseño de la estructura político-administrativa contra la corrupción en México: La Comisión Nacional Anti-Corrupción o la nueva herramienta derivada de la ley en proceso legislativo: El Instituto Nacional Anticorrupción y de Control no eliminarán la corrupción en el país porque se repite el modelo sustentado en la reforma de institucionales legales. La pretensión es modesta: mostrar cómo el modelo mexicano tiene una experiencia integral en el diseño de normas y estructuras administrativas, que no logran trascender al ámbito político y social donde la corrupción, como fenómeno complejo, se enraíza, destacando la desarticulación entre el desarrollo legislativo y la experiencia socio-política del Estado Mexicano en el combate a la corrupción, lo que puede servir de experiencia para que otros países diseñen sus herramientas para combatir la corrupción, en el artículo se cita a China, porque este artículo fue presentado como ponencia de la experiencia mexicana en ese país, es prudente aclarar que no se pretende ni se pretendió realizar una comparación sobre la corrupción y las estructuras legales entre ambos países, lo trascendente es analizar el caso mexicano.

From the perspective of control, the law is a tool and a technique. It is instrumental since it incorporates into the law specific behaviors to be imposed as mandatory for social agents, especially public servants, enforcing obligatory margins of action through control by objectives. As a technique, the law defines the processes, methods and forms of action of controlled entities in performing their activities. It also provides a framework of understanding between society and the government, which identifies the law as a means of interpreting authoritative decisions.

Mexico's administrative law has various anti-corruption mechanisms: constitutional provisions and principles; means for entering public service, the law of competence, and responsibility and accountability laws.

The design of Mexico's anti-corruption law can be divided into four phases: 1. from the pre-Hispanic era to the Colonial era; 2. from Mexican Independence to 1867 with the enactment of the so-called Ley Juárez [Juarez Law]; 3. from the Ley Juárez to the reform under Lopez Portillo; and lastly, 4. from the 1982 Anti-Corruption reform to now, when Mexicans are discussing the creation of an Anti-Corruption Commission.

A. In the early days, the Mexica political organization consisted of a Tlatoani (“the speaker, the boss”), the highest civil, military, judiciary and religious authority. There also was a Cihuacóatl (“female serpent”), who accompanied the Tlatoani in all public acts (military, political or religious) and who could stand in for him in the performance of any of his functions. Together, they represented the duality of cosmic forces: the celestial and the astral, day and night, masculine and feminine.

The highest authority in the Mexica fiscal organization in charge of controlling revenues was the Cihuacóatl, who monitored the distribution and appropriate use of resources. Under his authority, there was the Hueycalpixque or Grand Calpixque, in charge of bookkeeping and the collection of what the minor Calpixque gave him. These were the first anti-corruption institutions in Mexico.

In the Colonial era, the king was the absolute master of finances in the government of the New Spain. The Council of the Indies performed district inspections and reviewed books. The House of Trade in Seville governed all trade issues. The Treasury Board was the direct representative of the king's authority and as such, it oversaw all the branches of the administration, including finance and the army. Despite the power invested in the Treasury, its counselors were subject to a trial called “Residencia” [judicial review].1

On the viceroy depended the kingdom's checkboxes, private treasuries, and the court of auditors, and finally in the administration of New Spain were other royal officials. Another anti-corruption mechanism in place was the impeachment process.

According to Carmelo Viñas Mey, all members of civil government, the Church and the military, from the Viceroy to the lowest-ranking officer could be subjected to an impeachment trial. Residencia judges announced the opening of such trials, so that anyone who wished to file any grievances could do so. A trial of this type would be duly evaluated within six months, and sent to Spain for the Indies Council to issue the corresponding ruling. If found guilty, the public servant was required to pay compensation to the injured party; if he did not, the State would.2

B. Independent Mexico modeled its own constitution on the Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy promulgated in Cadiz on March 19, 1812. It was enacted in in Mexico on September 8, 1812. Article 227 of the Mexican Constitution of 1812 imposes the obligation of the Secretaries of State to draft annual budgets and pay any expenditure incurred. Article 331 sets forth the duty of the Secretaries of State to submit their budgets to the Congress in order to establish the costs and contributions needed to cover said expenditures. Article 345 established a national treasury that could dispose of any State revenue as it saw fit. As an internal control mechanism regarding the revenues in the Treasury, Article 348 established the Accountants Securities and Distribution of Public Accounts that could audit the general treasury to verify that the accounts were kept with due “transparency”. Furthermore, Article 350 created the Senior Accounting Office/Controllership to examine all accounts of public funds/public fund accounts. To complete the system, Article 261 allowed the Supreme Court to hear matters of residencia.

Two trends were vying for office's finance organization: the concentration of income and expenses, and the separation between the roles of income and expenses.

The first model of control in the 19th century was developed by José Ignacio Esteva, the Finance Minister of the Guadalupe Victoria administration.3 Its legal expression can be found in the “Arrangement Treasury Management Law” of November 16, 1824, which placed public finance management and administration under the domain of a single ministry. A Department of Account and Reason was created to take over the responsibilities of the defunct General Accountant's Office, budgets and public accounts were regulated, and the Federal Treasury and the Office of the Auditor General were established to review and keep executive accounts.

The second model was sponsored by Rafael Mangino, who was finance minister under Anastasio Bustamante4 and an advocate for anti-centralization. Under Mangino's influence, Article 9 of the Law of October 26, 1830, extended the powers of the Treasury to relieving the Department of Account and Reason from elaborating the second part of the public account. The organization of this office was the responsibility of the Treasury, and therefore, the general police and other subordinate federal offices had to render their accounts to this office.

Article 14 of the Constitutional Bases of December 15, 1835, legally established the organization of public finances in all its branches, the use of the “double entry” method, the organization of a court of auditors and procedures of economic and contentious jurisdiction. The implementation of internal accounting, external control and legal-administrative control is clearly derived from this article.

Articles 47-50 of the third of the Seven Constitutional Laws of 1836 authorized Congress to hear common crimes and official crimes committed by certain officials, through a declaration of origin in the first case, and a hearing in the second. If found guilty of the charges against him, the accused could be removed from his post.

On May 25, 1853, the Decree and Regulations for the Settlement of Administrative Litigation was issued. This document establishes that administrative matters did not correspond to the judiciary. On June 1, 1853, the Commissioner General of the Army and Navy was changed and the Department Treasurers or Substations were ascribed to the new Commissioner. On June 28, 1853, the Code of Ethics for Finance Employees, which criminalizes embezzlement of public funds, entered into force.

Under Title IV “Accountability of Public Officials”, Articles 103 to 108 of the 1857 Mexican Constitution provided that members of Congress, Supreme Court officials and Secretaries of Office, were responsible for common crimes, misdemeanors or omissions incurred during their terms in office.

State governors were also accountable for any violations to the Constitution and federal laws. The same considerations applied to the nation's president; however, during his term in office, he could only be charged for treason, explicit violation of the Constitution, any attack against electoral freedom or local felonies.

In the case of common crimes, Congress acted as a grand jury to hear the charges filed against the accused. The grand jury aimed to declare with absolute majority of votes, whether the accused was guilty or not. If a guilty verdict was reached, the accused would be removed from his position and be subject to ordinary court action. If the outcome resulted in an acquittal, the official on trial could continue in the exercise of his duties. Without the required number of votes, all subsequent proceedings are dismissed.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court functioned as a sentencing jury for these cases. After hearing the accuser, the prosecutor and the defendant, the Supreme Court would proceed to apply, by absolute majority, the corresponding penalty stipulated by law. In civil lawsuits, no privileges or immunity were granted to any public official.

For other matters, Congress appointed employees of the Office of the Auditor General (Article 73) to review the accounts in question. Congress then proceeded to apply the corresponding sanctions for any legal or financial violations.

The Juarez Law of November 3, 1870, established the crimes, errors and omissions of federal senior officials. The official crimes included any attack against democratic institutions, the form of government or electoral freedom; the usurpation of authority; any civil rights violation and any serious breach of the Constitution. The sanctions consisted of removal from office and ineligibility to hold public office for 5 to 10 years. In the case of crimes, misdemeanors and omissions committed by officials, the grand jury established the guilt or innocence of the accused and the sentencing jury imposed the sanction.

C. The Porfirio Diaz Law dated June 6, 1896, called the “Regulatory Law of Articles 104 and 105 of the Federal Constitution”, established responsibility/accountability for crimes, misdemeanors, omissions and common crimes. The procedure in these cases was carried out before the grand jury and the sentencing jury.

The Constitution of 1917, promulgated on February 5 of that year, entered into force on May 1st. The Constitution established various rules regarding the internal control of the administration. For example, Article 73, Section VII, granted Congress the authority to impose the contributions/revenue required to cover the budget of expenditures while Article 74, Section IV, gave the Chamber of Deputies exclusive powers to approve the annual budget.

Article 75 stated on approving this budget, the Chamber of Deputies may not fail to set the remuneration corresponding to holding office, which is established by law. In the event of failing to do so, the amount fixed for the previous budget shall be tacitly renewed.

Article 90 established that the Congress shall establish the number of federal secretaries by law. Under the terms prescribed in Article 93, state officials are accountable to Congress for the state of their administrative branches.

Furthermore, Articles 108 to 114 under Title IV marks the differences between crimes and official misconduct. In the case of crimes, it is the responsibility of the Chamber of Deputies to set up a Grand Jury to establish whether there are grounds to proceed against the accused. In the case of official misconduct, it is the Senate which forms a grand jury to impose sanctions such as deprivation of office and ineligibility to hold public office.

Article 126 states that no payments may be made that is not included in the budget or provided for by a subsequent law. Likewise, Article 134 requires that all government contracts for public works should be awarded by auction, after a call for bids submitted in sealed envelopes and opened in a public meeting.

The Lázaro Cárdenas Law of December 30, 1939, called the “Act of the Responsibility of Officials and Employees of the Federation, the Federal District and Federal Territories and the High State”,5 regulated responsibility for crimes and official misconduct, allowing any citizen to report any such behavior. This law established the responsibility for crimes and acts of official misconduct committed by federal senior officials and employees. Official crimes consist of attacks against democratic institutions, the form of government and electoral freedom; the usurpation of authority; violations of civil rights and serious breaches of the Constitution.

This law contains five procedures: two for cases of official crimes and common crimes committed by senior officials, three for other employees brought before a jury of peers, and the last for unaccountable enrichment.

The Lopez Portillo Law of December 27, 19796, called the “Act of Responsibility of Officials and Employees of the Federal District and the High State Officials”, follows the system set in place by the Cardenas law. It established the responsibility of public officials for common crimes, official crimes and official omissions. This law defines official crimes as acts or omissions committed by officials or employees of the Federation or the Federal District, committed during their office or by reason thereof, which are to the detriment of public interest and the good offices.

Those considered official crimes were attacks against democratic institutions, the federal form of government and electoral freedom; the usurpation of authority; violations of the Constitution; serious omissions; civil and social rights violations, and acts that are detrimental to the public interest and the good offices.

D. Articles 108 to 114 under Title IV “Responsibility of public servants” of the Mexican Constitution were amended on December 28, 1982. This reform created the Office of the General Comptroller of the Federation, the now defunct General Accounting Office and the Ministry of Public Administration (currently being phased out). The Federal Law of the Responsibilities of Public Servants was also formed.

The importance of this reform was the establishment of the definition of a public servant, the obligation of federal and state governments to issue regulations on the responsibilities of public servants, the delimitation of the areas of political responsibility (faults or omissions that run contrary to public interest or the good offices), criminal responsibility (acts or omissions that constitute a crime) and administrative responsibility/accountability (actions affecting legality, honesty, loyalty, fairness and efficiency in the course of employment, position/term in office or commission), a list of matters of political judgment, and provisions for the establishment of secondary legislation on the responsibilities of public servants (liabilities, penalties, procedures and authorities to enforce them) and the corresponding statutes of limitations.

The Mexican Constitution currently in force regulates the responsibility of public servants in Articles 108 to 114 under Title IV. The articles 108, 109, 113 and 114 refer to the administrative control. Articles 110 and 114, first paragraph governs the impeachment process and Articles 111 and 112 the statement of origin7. We will briefly discuss this constitutional basis.

Thus, the legal instruments to combat corruption in Mexico appear to have been guided by clear objectives: a) to set ethical standards, b) to establish standards for public servants to follow, c) to regulate impeachment proceedings, statement of origin and criminal and administrative responsibility/ accountability, d) to determine penalties, and e) to respect civil equality.

II. The Legal Scope of Mexico's Administrative Law against CorruptionThe legal scope of Mexico's administrative law leads us to the sphere of internal control, which can be understood as the set of policies and procedures an institution establishes to obtain reasonable assurance that it will meet the proposed ends. Internal control is carried out by bodies within the administrative body. In the field of Mexico's public administration, specialized organs called internal comptrollers are responsible for this control. In the case of active public administration external control is directed by the Court of Accounts, as bodies with the legal authority to review public accounts and establish the responsibilities of public servants for any misuse of public resources.8

In addition to the legal instruments mentioned in the previous section, Mexico has other tools to tackle corruption. These include the National Human Rights Commission (1990), the Federal Law on Administrative Procedure (1995), the Organic Law of Federal Public Administration (1996 legal reform), the Federal Law of the Responsibility of Public Servants (1999 legal reform), and the Chief Audit Office of Mexico (1999). Furthermore, amendments were made to the Federal Tax Code and the Regulations of the General Accounting Office (2001), the Federal Law of Administrative Accountability of Public Servants and the Federal Law of Transparency and Access to Public Government Information (2002).

On April 11, 2003, the Law on Professional Career Service in Federal Public Administration was approved. It is expected that this statute will bring stability and permanence to the public servants in their employment, office or commission.

The Federal Anti-Corruption Law in Public Contracts was created on June 11, 2011. This law is based on international conventions for the prevention and combat of corruption, such as the Inter-American Convention against Corruption, the Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions, and the United Nations Convention against Corruption.

The work of corruption control is performed by formal and material administrative bodies. It consists of the use of legal methods to remove or correct illegal or ineffective governance through technical means called “administrative procedures”, which are, properly said, administrative controls, audits and processes for determining the legality of the acts of administrative authorities.9

In this manner, the first paragraph of Article 108 of the Constitution establishes who should be considered public servants for the purpose of the accountability for their acts, omissions or administrative violations incurred in the performance of their duties. Thus, public servants are elected representatives, members of the Federal Judiciary and the Mexico City Judiciary, officials and employees and in general, anyone who holds a position, office or commission of any kind in the federal public administration, the administration of the Mexico City administration or the Federal Electoral Institute.

Article 109 refers to the types of offenses which may be incurred by public servants, namely of a political, criminal and administrative nature. Section III of this law stipulates that: administrative sanctions apply to public servants for acts or omissions that affect the legality, honesty, loyalty, fairness and efficiency that should be observed in the performance of their jobs, positions, or commissions. It also establishes the autonomy of the procedures for the application of sanctions for liabilities incurred by public servants and notes that penalties of the same kind cannot be imposed twice for a single act.

Article 113 outlines the necessary content for laws on administrative responsibilities. Subsequent statutes must set out the obligations of public servants, the sanctions for any breach of these, the procedures for the application of the sanctions and the competent authorities to enforce them. The article states that, in addition to those provided by law, sanctions shall consist of dismissal, suspension, disqualification and fines not to exceed three times the profits made or damage and injury caused. Lastly, the final paragraph of Article 114 states that the laws shall determine the statute of limitations, but when the acts or omissions are serious, it may not be less than three years.

At the federal level, the Federal Law on Administrative Responsibilities of Public Servants is regulated by Title IV of the Mexican Constitution, as regards the subject of administrative accountability, the obligations of public service, responsibilities and administrative sanctions, the competent authorities and rules for the implementation of sanctions, and the registry of public servants’ assets.

It consists of four sections. The first sets out the general provisions, the second deals with “administrative responsibilities”, the third is related to the “Registry of Assets Declarations of Public Servants” and the fourth refers to the “preventive actions to ensure the proper exercise of public service.”

The above-mentioned law applies to federal public servants and all persons who handle or utilize federal resources. This leads us to conclude that hypothetically, public servants pertaining to the states or municipalities or even any individual who handles federal resources can be penalized under the terms of this statute.

The bodies responsible for enforcing the law include the Congress, the Federal Judicial Power, the Ministry of Public Administration, the Federal Tax and Court, labor and agrarian courts, autonomous bodies like the Federal Electoral Institute, Chief Audit Office, National Human Rights Commission, the Central Bank and other courts and institutions established by law.

The internal comptrollers and the audit leaders, as well as the complaints and accountability departments of the internal control bodies have the authority to investigate, process, substantiate and resolve the procedures and remedies provided by law. When the acts or omissions regarding the allegations are found in more than one case to be sanctioned, the respective procedures are carried out autonomously in the corresponding jurisdictions, but always following the “non bis in idem” principle.

Twenty-four rules regulate the obligations of public servants. Any failure to fulfill the obligations will lead to prosecution and the corresponding sanctions, without prejudice to the rules governing the armed forces.

One innovation is that it establishes a series of prohibitions applicable to public servants after they leave their jobs, positions or commissions. These include prohibiting counselors and electoral magistrates from participating in any public office in the administration headed by whoever won the election they organized or certified.

A regression in this matter is the obligation imposed on the accuser or petitioner stating that “complaints and denunciations shall contain data or any evidence of the alleged responsibility”. The Federal Law of the Responsibilities of Public Servants (1982) only regulated grievances or complaints, without requiring data or evidence of responsibility. The Federal Law of the Administrative Accountability of Public Servants (2002) was drafted with the ordinary citizen in mind because it requires evidence of the responsibility. This leads to the conclusion that the administrative authorities failed to fulfill their duty to investigate acts of presumptive responsibility, wrongly forgetting the nature of public procedures. This is even more absurd when it comes to complaints in which the plaintiff lacks evidence. It is well known that on several occasions evidence is destroyed, altered or hidden. Therefore, it follows that plaintiffs’ complaints should be sufficient grounds to initiate an investigation.

The Federal Law of the Administrative Accountability of Public Servants regulates the administrative sanctions to be imposed on offenders: a) a public or private reprimand, b) suspension of employment, position or commission for a period of no less than three days or more than one year, c) removal of the post and economic sanctions, or d) temporary disqualification. It also eliminates the private or public caution (amonestación) as an administrative sanction, which is a step forward because it prevents confusion with a warning formulated in a process against one of the parties. It also establishes rules regarding gains or loss or when damages are incurred, and states that disentitlement cannot be for a term less than ten or more than twenty years. In the case of serious behavior, the offender must be debarred.

In the event of the hiring of a person who has been debarred, the Ministry of Public Administration must be notified with the proper grounds and justification for this re-hiring.

This law also typifies offenses that should be considered serious. These offenses are performing duties of employment after the period of designation; authorizing the selection, recruiting or appointing disabled staff; intervening in matters in which the public servant has a personal interest; soliciting, accepting or receiving a gift; unduly intervening in the selection, nomination, appointment, hiring, promotion, suspension, removal, dismissal, termination or sanction of any public servant; refraining from responding promptly to instructions, requests or orders from the Ministry of Public Administration; refraining from submitting timely and truthful information required by the National Human Rights Commission; taking advantage of one's hierarchical position to prevail upon another public servant to perform or not perform acts for personal gain; and purchasing properties related to public or private investments that may yield gains of which the public servant becomes aware of in the performance of his duties. This is commendable because it breaks with the discretion of the previous law and gives legal certainty to public servants.

It also sets up three goals for imposing economic sanctions when there is harm or gains.

Another innovation is regulated in Article 16, which refers to the provisional seizure of goods. In the opinion of the Ministry of Public Administration, the comptroller or head of the area of accountability can confiscate assets when the suspects disappear or there is imminent risk of concealment, disposal or squander, which again opens a wide margin of discretion.

To date, this is the state of Mexico's anti-corruption instruments, its values, rules and procedures. However, it is necessary to show how efficient these instruments are. In this study, we will analyze the political problem and the social aspect of corruption.

III. Evaluation of Legal and Administrative Tools against CorruptionIn order to face the problem of corruption, specialized administrative structures can be found within the inter-organic and intra-organic sphere of the State: internal and external control, like venues for social defense in the fight against corruption or to act against corrupt practices. These agencies are given specialized functions: internal control bodies aid in the management, internal control and evaluation of public administration performance; external control agencies are reserved the right to perform external audits; that is, an ex-ante review of public expenditures using government auditing techniques, the review of public accounts and the evaluation of its activities.

Two paradigmatic examples of this are the Ministry of Public Administration and the Federal Office of the Auditor General.

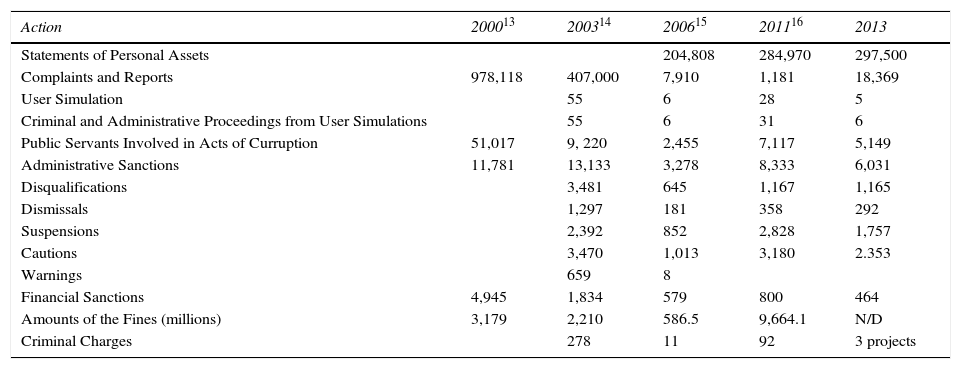

According to the 1st Progress Report for 2012-2013, the Ministry of Public Administration has focused on closing loopholes against corruption, not only those that can arise from the interaction between public servants and citizens during routine activities concerning the goods and services provided or acquired, but also those that are caused by not complying with their responsibilities in the line of public administration.10

The report also sustains that Federal Government management is primarily overseen by the Internal Control Bodies through the performance of its Annual Auditing Programs. The Ministry of Public Administration follows up on the audits carried out and assists in the process to eliminate findings. In the first half of 2013, 844 audits were performed and 4,536 of 7,682 findings were dealt with. In 248 cases, it is estimated that the improper behavior of public servants and/or possible harm to institutional assets totaled $980.7 million Mexican pesos. If the no explanation or justification for this amount is not provided, the cases will be turned over to the corresponding Internal Control agency departments for them to determine where the responsibilities lie and recover the public funds, where appropriate.11

Some of the most important activities of this federal public administration agency are that: …it oversees the proper behavior of public servants by means of annual statements of personal assets. Between January 1 and June 30, 2013, a total of 297,500 statements were received, 33,474 of which were statements rendered for the first time; 240,147 were annual amendment statements and 23,879 were statements rendered on the completion of their assignment.

Citizen complaints and reports are another source that provides information about public servants’ possible violations of the law. Between December 1, 2012 and July 29, 2013, 18,369 complaints and reports were processed and attended by internal control bodies and the Ministry's Internal Comptroller.

To unequivocally detect acts of corruption involving public servants, a User Simulation mechanism was implemented 5 times between December 1, 2012 and July 31, 2013. As a result, administrative and criminal proceedings were initiated against 6 public servants.

After several interventions, 6,031 administrative sanctions were carried out on 5,149 public servants in the Federal Public Administration: 1,165 officials were disqualified, 1,757 were suspended and 2,353 received a public or private caution.12

However, a comparison of the main actions found in the above reports shows that:

| Action | 200013 | 200314 | 200615 | 201116 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statements of Personal Assets | 204,808 | 284,970 | 297,500 | ||

| Complaints and Reports | 978,118 | 407,000 | 7,910 | 1,181 | 18,369 |

| User Simulation | 55 | 6 | 28 | 5 | |

| Criminal and Administrative Proceedings from User Simulations | 55 | 6 | 31 | 6 | |

| Public Servants Involved in Acts of Curruption | 51,017 | 9, 220 | 2,455 | 7,117 | 5,149 |

| Administrative Sanctions | 11,781 | 13,133 | 3,278 | 8,333 | 6,031 |

| Disqualifications | 3,481 | 645 | 1,167 | 1,165 | |

| Dismissals | 1,297 | 181 | 358 | 292 | |

| Suspensions | 2,392 | 852 | 2,828 | 1,757 | |

| Cautions | 3,470 | 1,013 | 3,180 | 2.353 | |

| Warnings | 659 | 8 | |||

| Financial Sanctions | 4,945 | 1,834 | 579 | 800 | 464 |

| Amounts of the Fines (millions) | 3,179 | 2,210 | 586.5 | 9,664.1 | N/D |

| Criminal Charges | 278 | 11 | 92 | 3 projects |

With reservations and keeping it in proportion, it can be observed that 978,000 complaints and charges were filed in 2000. After that year, this figure gradually decreases so that by 2013, only 18,000 complaints and reports were filed. If the figure for 2000 represents 100%, the number of complaints and reports drops to 1.84%. In other words, either Mexico substantially improved its federal public administration, or people stopped believing in one of the tools to fight corruption.

In 2000, the number of public servants involved in acts of corruption stood at 51,000, but by 2013, there were only 5,000. This shows a 9.8% decline in the number of public servants involved in corruption. This leads us to think that either public administration is more honest or that concealment and impunity mechanisms are not produced by the bodies in charge of internal control.

In terms of administrative sanctions, it can be seen that the figure went from 11,000 to 6,000 over the same period, which translates into a reduction of 54.5%. Again, it must be noted that this is due to either successful changes in Mexico's public administration or the inefficiency of organic internal control mechanisms.

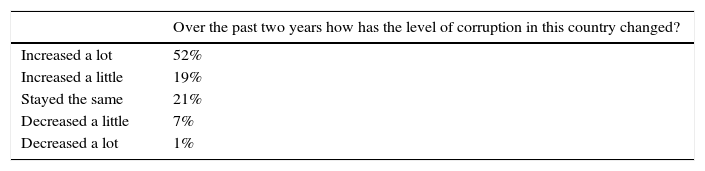

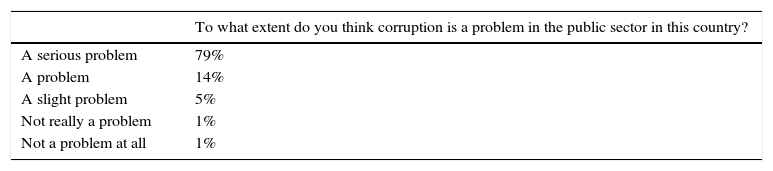

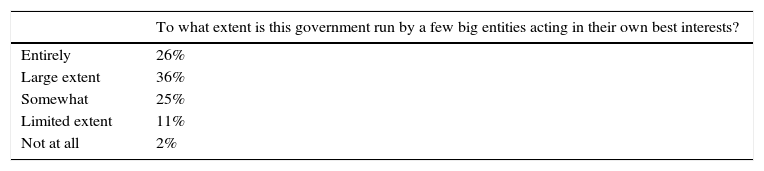

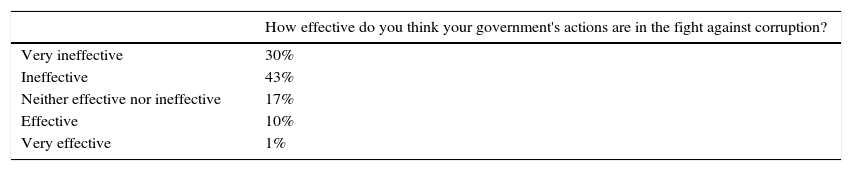

The above can be compared with what Transparency International's Global Corruption Barometer17 has published on Mexico, as seen in the following table:

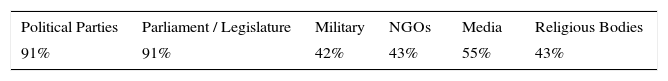

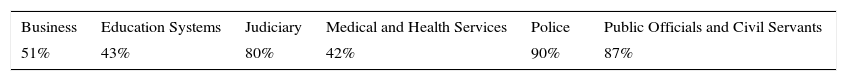

However, when asked about the percentage of corruption in the country's institutions, the vast majority of the respondents felt that institutional structures were highly corrupt, as shown below:

When asked if they or anyone in their households paid a bribe in the last 12 months, 55% of the respondents reported having paid a bribe to the judiciary, 61% to the police, 17% for education services, 31% for land services, 16% to the tax revenue, 17% for utilities, 27% for registry and permit services, and 10% for medical and health services.

According to the Corruption Perceptions Index, Mexico stands in 106th place out of 177, with a score of 34/100, with scores ranging from 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean). The Bribe Payers Index puts Mexico in 26th place out of 28 with a score of 7.0/10, noting that the higher the score, the lower the likelihood of companies from this country to pay bribes when doing business abroad.18

The only plausible conclusion from this information is that it highlights the negative aspects of the information the government has submitted on internal control, which in turn shows that the legal and organic structures are insufficient and inefficient to fight corruption.

Meanwhile, in the scope of external control, as a technical body of the Chamber of Deputies, the Office of the Auditor General performs audits to the three branches of power, constitutionally autonomous federal agencies and any public institution that use federal funding, including states, municipalities or individuals. Moreover, it has the authority to establish responsibilities for damages directly and impose fines and sanctions.

As seen, there is an oversight body with the authority to audit revenues and expenditures; the handling, custody and use of funds and resources by the three branches of power and federal public entities; and the compliance of the objectives set forth in federal programs, among its many functions associated with proper administrative management.

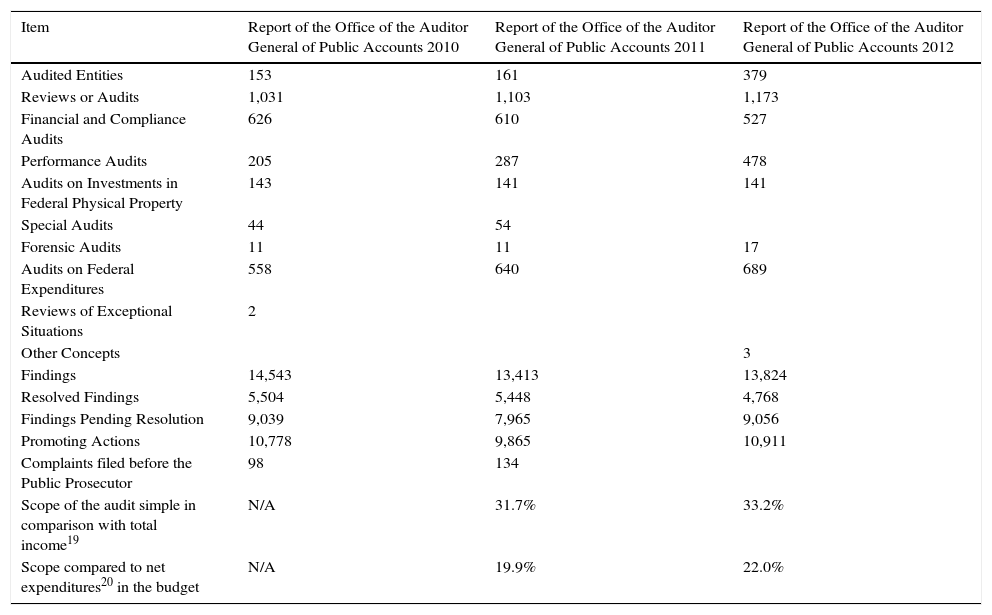

On analyzing the contents of the Report of the Office of the Auditor General of Public Accounts for 2010, 2011 and 2012, we can see:

| Item | Report of the Office of the Auditor General of Public Accounts 2010 | Report of the Office of the Auditor General of Public Accounts 2011 | Report of the Office of the Auditor General of Public Accounts 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Audited Entities | 153 | 161 | 379 |

| Reviews or Audits | 1,031 | 1,103 | 1,173 |

| Financial and Compliance Audits | 626 | 610 | 527 |

| Performance Audits | 205 | 287 | 478 |

| Audits on Investments in Federal Physical Property | 143 | 141 | 141 |

| Special Audits | 44 | 54 | |

| Forensic Audits | 11 | 11 | 17 |

| Audits on Federal Expenditures | 558 | 640 | 689 |

| Reviews of Exceptional Situations | 2 | ||

| Other Concepts | 3 | ||

| Findings | 14,543 | 13,413 | 13,824 |

| Resolved Findings | 5,504 | 5,448 | 4,768 |

| Findings Pending Resolution | 9,039 | 7,965 | 9,056 |

| Promoting Actions | 10,778 | 9,865 | 10,911 |

| Complaints filed before the Public Prosecutor | 98 | 134 | |

| Scope of the audit simple in comparison with total income19 | N/A | 31.7% | 33.2% |

| Scope compared to net expenditures20 in the budget | N/A | 19.9% | 22.0% |

N/A = no available information.

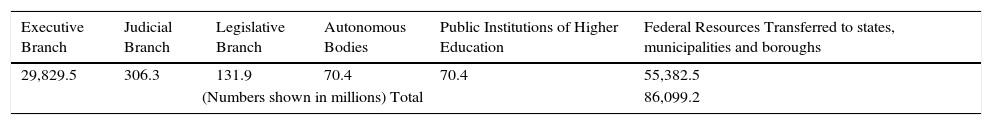

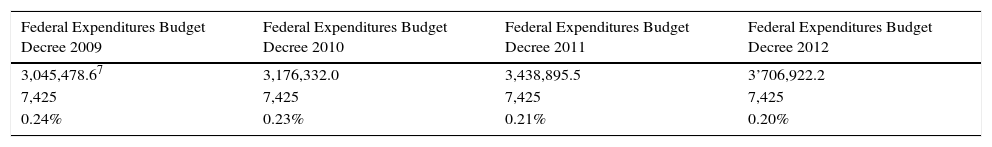

Furthermore, the Report on the Resources Recovery by the Office of the Auditor General of Public Accounts between 2001 and 201221, dated March 31, 2014, shows that the Office of the Auditor General recovered:

If we divide this amount by the twelve months that the ASF spent on this activity, it can be said that the ASF is recovering approximately 7.42 billion pesos. However, on comparing this amount with the total budget handled by the Mexican public spheres, the following can be observed:

What it does show is that only 0.2% of the annual budget has been recovered.

However, it should be pointed out that the actions the Office of the Auditor General takes against corruption is hindered by many factors. First of all, there are the absurd principles of “annuality” and “posterity”, which hamper more efficient actions in terms of government audits. There is also the problem of forwarding its findings regarding administrative responsibility to the federal, state or municipal internal control bodies, which do not recognize the work carried out by the ASF and begin their own “investigation”. This leads to losing precious time to establish responsibilities. Another problem can be seen in criminal matters, since oftentimes public prosecutors and judges are not aware of the nature of the ASF's legal authority. Thus, these judicial authorities require the ASF to ratify expert opinions on authorship, give scant value to the ASF investigations, and in extreme cases, argue that the crime manifested in the ASF's filing charges is not “typified” regardless of all the evidence presented.

All of the above shows the dysfunctional nature of the Mexican anticorruption model: it has the laws and the institutions, but little or no effectiveness.

IV. The Political ProblemCorruption involves activities that take place in the public space, but which transcend the public space and are rooted in the private space. One example is the word “corruption” and its delimitations. For Susan Rose-Ackerman, “corruption is a symptom that something has gone wrong in the management of the state. Institutions designed to govern the interrelationships between the citizen and the State are used instead for personal enrichment and the provision of benefits to the corrupt. The price mechanism, so often a source of economic efficiency and a contributor to growth, can, in the form of bribery, undermine the legitimacy and effectiveness of government”.22

Dontella Della Porta and Alberto Vannului hold that “corruption refers to the abuse of public resources for private gain, through a hidden transaction that involves the violation of some standards of behavior”.23

In an analytical approach, Robert klitgaard believes that corruption may be represented by the following formula: C=M+D-A (corruption equals monopoly plus discretion minus accountability). In his opinion, corruption is usually encountered when an organization or person has the monopoly over a good or service, has the discretion to decide who will receive it and how much that person will get, and is not held accountable. Furthermore, corruption is a crime of calculation not of passion.24

In the Mexican legal system, public servants are constrained in their actions by the entreaty they make and that is enforced by the Constitution and the laws deriving from it. The Federal Law of the Responsibilities of Public Servants establishes an ethical framework with which compliance is imposed on public servants to safeguard fairness, honesty, legality, effectiveness and efficiency in public employment.

The problems in the use and allocation of public resources are recurrent in societies like Mexico where corruption resizes the forces of the institutions responsible for its eradication. No need for further discussion on the subject since there is a rich history that can inform us on this matter.

In our opinion, the principal problem relates to the “politicization” of control. The administrative authority steers this type of control. However, senior officials and employees are members of political parties, which is a reason why the controls do not work properly. We can find many examples of violations of the legal procedure and material law in cases in which politicians are involved.

The succeeding list presents recent cases where we can find public servants engaged in the illegal use of power:

- A)

Governors of many states —including those from Tabasco, Coahuila, Aguascalientes, Tamaulipas, Baja California Sur, Chiapas, and Quintana Roo— have been some of the most well-known cases of offenders, with allegations involving missing public funds (reaching hundreds of millions of dollars), collaboration with drug traffickers, murder, and money laundering. Public figures once considered untouchable, such as the former head of Mexico's Teachers Union, Elba Esther Gordillo, were publicly pilloried and arrested.25

- B)

Andrea Benítez (the daughter of Humberto Benítez, the head of Mexico's Office for Consumer Protection) became known as #LadyProfeco when she threatened to shut down a trendy bistro in Mexico City, after being denied her preferred table.26

- C)

The former governor of the southern state of Tabasco went before a judge at a Mexico City prison and was arraigned on charges of tax evasion and use of illicit resources. He declined to enter a plea.27 Andrés Granier has a sumptuous wardrobe and lifestyle. He has bragged about owning 400 pairs of shoes, 300 suits and 1,000 shirts, purchased from luxury stores in New York and Los Angeles.28

In these corruption cases, the common denominator is the pursuit for income. In words of Anne O. krueger, in many market-oriented economies, government restrictions upon economic activity are pervasive facts of life. These restrictions give rise to income of a variety of forms, and people often compete for this income. Sometimes, such competition is perfectly legal. In other instances, income seeking takes on other forms, such as bribery, corruption, smuggling, and black markets.29

V. The Social AspectIn Mexico, citizens experience palpable discomfort when approaching the authority to carry out administrative procedures. Given the complexity of the bureaucracy, the number of requirements to be covered for any process and the long lines to wait, many prefer to recur to various forms of corruption. Administrative and management procedures are insufficient to guarantee a civil service that serves the governed.

Society should be able to seek a communitarian purpose into the future. That purpose is the common good. This is important for our study since our concepts of control and the application of rules and procedures are set within a frame of reference: that amorphous element called society. Control, justice and procedures are specific to this medium called society.

The individual and society must share principles by which rules are made effective, but the public and private sectors also interact in ways that cannot be solved through regulations. The law is always expressed in some kind of language. However, there is a separation between words and deeds. Laws are tools that are limited in the fight against corruption.

The Business Anti-Corruption Portal said, “Corruption is on the increase, with the total bribes paid in Mexico rising by 18.5% to USD 2.75 billion in 2010, according to a TI Mexico survey”.30 In its “Corruption Perceptions Index 2012, International Transparency places Mexico in 105th of 176, where 1 is less corrupt and 176 is more corrupt, with a score of 34/100. This shows that Mexico is a highly corrupt country. In the 2011 Bribe Payers Index Report 2011, Mexico was in the 26th place with a score of 7.0/10, which means that Mexican companies pay bribes when doing business.31

According to Nubia Nieto, the democratic transition in Mexico and the development of globalization have contributed to the increased power of organized crime, making it more difficult to fight against narco-trafficking. Historical social problems (high levels of unemployment illiteracy, the exclusion of indigenous communities, alcoholism, drug addiction, the disintegration of families, low levels of social mobility, high levels of social inequality, a decline in ethical and moral principles, disappointment in political changes and democratic values, impunity and corruption, and a negative perception of the police and the judiciary) are some of the main causes that have contributed to increase levels of narco-trafficking in Mexico.32

Mexico's “democratic transition” focuses on free market reforms. In this sense, Jagdish Bhagwati states his opinion, saying, “let me say emphatically that the absence of economic freedom is an ally of corruption. True, corruption has many fathers. But the most fertile and fecund father is what Indians call a “permit raj”, i.e. an economic regime where governments demand that permits be procured to produce, to import, to invest, to innovate, to do almost anything! It needs no particular gifts to see that such an economic regime leads to cataclysmic levels of corruption, as it did in South Asia. It also corrupts even democratic and quasi-democratic regimes into “crony capitalism” as in some segments of the economy in Indonesia”.33 Paradoxically, the free market is an open space for corruption.

VI. The Future of Mexican Legislation against Corruption: “The National Anti-Corruption Commission” and the “NationalAnti-Corruption and Control Institute”The new administration under Enrique Peña Nieto proposed the creation of National Anti-corruption Commission in November 15, 2012. The proposal aims to form a new National Anti-Corruption Commission which will have an impartial system of accountability and administrative responsibility.

Rodrigo Aguilera affirms that “with the PRI keen on presenting itself as a renovated political force, it was not surprising, therefore, that Peña Nieto announced an anti-corruption bill as one of his first initiatives. The bill, sent to Congress on November 14th, seeks to create an anti-corruption commission (Comisión Nacional Anticorrupción or CNA) which will be tasked with investigating corruption cases at a federal level and against individuals. It will also have the ability to tackle cases at a state and municipal level, but only if they have national repercussions. Crucially, the commission will be able to sidestep legal hurdles such as bank and fiscal secrecy which would, in theory, make it a powerful tool against money laundering. In order to avoid duplication of roles, the existing Secretaría de la Función Pública (a public administration ministry) would be eliminated, and its current duties shared between the CNA and the treasury”.34

The proposal emphasizes that the new body will act on its own in matters concerning the notification of other organs of State or public complaints or reports that indicate probable cases of corruption. A highpoint in the powers proposed by the president for this National Anti-Corruption Commission is the fact that their investigation will not be hampered by bank, fiduciary or tax secrecy.

In addition, within the functions of the proposed anticorruption commission, the commission will be able to exercise drawing authority on corruption cases that arise in states and municipalities when it is necessary to be more partial due to the relevance of the investigation. Besides the proposal for the creation of the National Anti -Corruption Commission, there is the intention of forming a National Council for Public Ethics that will be comprised of experts who can make recommendations on transparency.

In his article entitled “Myths and Realities of the National Anti-Corruption Commission”, Mario Ismael Amaya Baron35 affirms “one of the lines of action of the government headed by Enrique Peña emphasizes the fight against corruption, whose levels estimate 9% of the GDP.” For this, he has proposed the creation of a national anti-corruption system charged with establishing a National Commission and state commissions with powers of prevention, investigation, administrative punishment and to denounce any act of corruption to the authorities, among other measures.

Amaya Baron mentions three current reforms on corruption and transparency as proposed by the President: 1. The creation of a National Anti-Corruption Commission (CNA) 2. The expansion of the powers of the Federal Institute for Access to Information and Data Protection (IFAI) to include the affairs of states and municipalities, and 3. The creation of a body comprised of citizens to monitor official advertisement bought from the media.

Moreover, Amaya Baralso sustains that “public corruption is an unlawful behavior (act or omission) of the special duties the public servant has towards the State, to unduly favor himself or a third party for a benefit. The concept of corruption should avoid empty or indeterminate categories that threaten the democratic State, and therefore, statutory categories or administrative offenses of corruption must be specifically established.”

In the design of Mexico's Anti-Corruption Commission, Amaya Baron holds that: In the labor of developing the National Anti-Corruption Commission, on November 15, 2012, Revolutionary Institutional Party Senator Lizbeth Hernandez Lecona and Green Party Senator Pablo Escudero Morales presented the initiative that empowers Congress to enact laws to combat corruption, such as the Federal Anti-Corruption Act and the approval of the decree establishing the commission.

The Anti-Corruption and Citizen Participation Commission of the Senate, established on October 2, 2012, and comprised of PRI Senators Arely Gomez, Ana Lilia Herrera and Daniel Amador Gaxiola Alzado; PAN Senators Marisela Torres Peimbert, Laura Rojas and Roberto Gil Zuarth; PRD Senators Angelica de la Peña and Manuel Camacho Solis, and PVEM Senator Pablo Escudero, is responsible for reviewing the initiative and presenting it to the Senate.

Let us discuss the initiative to create the National Anti-Corruption Commission, amending Articles 22, 73, 79, 105, 107, 109, 113, 116 and 122 of the Federal Constitution.

The first article of the draft decree, which amends the second paragraph of Article 22 of the Constitution, does not consider administrative offenses related to corruption that gives rise to forfeiture since forfeiture can be a criminal or administrative sanction.

The second article, which amends Section XXIX-H and adds Section XXIX-A of Article 73 of the Constitution, abolishes the legal power of the Federal Tax Court, that was never used, regarding the imposition of sanctions to public servants for administrative responsibility as determined by law, establishing the rules for its organization, operation, procedures and appeals against its decisions, as stated in the constitutional reform, published in the Official Federal Gazette on December 4, 2006.

Regarding Article 5, which amends Section V of Article 107 of the Constitution, it should be considered that the National Anti-Corruption Commission is an autonomous body, not a court per se, so its decisions can be argued before district courts dealing in with administrative matters.

As to Article 6, which amends and supplements Section III of Article 109 of the Constitution, the laws of the administrative responsibilities of public servants should enshrine the rights within the context of disciplinary proceedings, congruent with the constitutional reform on human rights, published in the Official Federal Gazette on June 10, 2011.

When discussing and approving the initiative, the permanent legislature must consider that sanctions are not only imposed, but also executed. Therefore, the implementation phase of disciplinary proceedings under the auspices of the National Anti-Corruption Commission should also be considered. In regards Article 7 that amends and supplements Article 113 of the Constitution, we believe that the procedures to combat corruption are: the procedure of administrative liability of public servants and the criminal procedure. However, corruption can be fought through the procedure of responsibility for damages, which is carried out by the Office of the Auditor General, and the civil procedure to redress the damage and the liability of the State, among others.

Furthermore, a new law for the National Anti-Corruption Commission should be created. It must give an in-depth description of its powers, composition, and disciplinary procedures for majority decision- making, among other things. It must be stated that the committee will apply the Federal Law of the Administrative Responsibilities of Public Servants and the Federal Anti-Corruption Law, which shall establish the alleged administrative offenses (acts or omissions) that cause corruption, procedures, penalties and administrative execution. The resolutions of the commission should not be considered judgments since this body is not an administrative court. But if the National Anti-Corruption Commission investigation results in an act (or omission) that constitutes a crime of corruption, the Federal or local Prosecutor should be notified, where appropriate. In addition, it should be noted that corruption cases do not prescribe administrative responsibilities for a period of less than five years and that any act of corruption is serious, so once the investigation begins, temporary suspension of public service ensues.

The National Council for Public Ethics should reiterate the ethical values of public servants, issuing a Single National Code of Public Ethics, enforceable in all areas whether federal, local or municipal.

This comprehensive reform should be about jurisdiction in disciplinary liability for acts or omissions that give rise to corruption. For example, the Federal Judiciary Council and internal comptrollers of both houses of Congress should be stripped of administrative responsibilities, with which the existence of these public bodies is unlikely, since their disciplinary roles would become part of the role of the National Anti-Corruption Commission.

Finally, Amaya Baralso concludes that a“Single Anticorruption Code that encompasses any misconduct in the three branches of government, judicial, legislative and executive, as well as autonomous bodies, should be created since such conducts are dissimilar”.36

However, the creation of the National Anti-Corruption Commission is still under deliberation in the Mexican Congress. Additionally, no political will for the combat of corruption is perceived. Therefore, we are not optimistic about the future of this commission.

The various points of views of corruption can be found in works of Alberto Ades and Rafael Di Tella, are found based on different perspectives a) legal (Italian Judge Antonio Di Pietro), b) commercial (Robert klitgaard, Timothy Besley and John McLaren), and c) economic (Susan-Rose Ackerman). They sustain that lawyers often argue that the way to reduce corruption is to reform the legal system so as to increase the punishment for malfeasance. Businessmen sometimes suggest that the problem of corruption lies in the low salaries bureaucrats receive compared to those of private-sector employees with comparable responsibilities. Accordingly, they argue that bureaucracies should be run like private companies and the wages of public servants should be raised. The economist's natural approach to corruption control is to appeal to the concept of competition, as it is argued that bribes are harder to maintain where perfect competition prevails.37

As seen, the Mexican State wants to combat corruption with ineffective formulas. Examples of this can be found in the case of the debate regarding the reform to Articles 16, 21, 76 and 109 of the Constitution and the enactment of the Organic Law of the National Anti-Corruption and Control Institute,38 approved by the Chamber of Senators and under deliberation in the Chamber of Deputies. This simply reflects how the past experience described above can be forgotten.

In creating an anti-corruption agency, there are several lessons to be learned, but three stand out: a) considering the problem to be addressed, it should not be forgotten that corruption has multiple facets, b) developing legal and organizational tools to fight corruption should be aimed for a specific sector of society; and c) citizens should be wisely involved in this effort. Corruption is not eliminated by creating “laws” and “agencies”, but by generating an important impact on the political-social conventions so as to reject this practice.

Within this context, we cannot forget Article 3 of the Chinese Constitution, which states that “The State organs of the People's Republic of China apply the principle of democratic centralism. The National People's Congress and the local people's congresses at different levels are instituted through democratic elections. They are responsible to the people and subject to their supervision. All administrative, judicial and procuratorial organs of the State are created by the people's congresses to which they are responsible and by which they are supervised.” In this article, the principle of responsibility stands as an important tool against corruption. Therefore, it is possible for Chinese positive law to take advantage of Mexico's experience in the struggle against corruption.

He is a researcher at the Institute for the Legal Research at the UNAM and a Level II Researcher in the National System of Researchers (SNI-CONACYT). The author thanks Pastora Melgar Manzanilla and Mirta E. Rocha Piña for their help in the translation of this article.

Residencia was a kind of judicial review that applied to public officials in Mexico at that time. It was basically an impeachment trial in which public officials were liable for the charges against him.

Carmelo Viñas Mey, El régimen jurídico y la responsabilidad en la América indiana55-56 (unam 1993).

President of Mexico from 1824 to 1829.

President of Mexico from 1830 to 1832 and from 1837 to 1839.

Ley de responsabilidades de los funcionarios y empleados de la Federación del Distrito y Territorios Federales [L.R.F.E. F.F.T.F] [Act of the Responsibility of Officials and Employees of the Federation, the Federal District and Federal Territories and the High State] as amended, Diario Oficial de la Federación [D.O.], 21 de Febrero de 1940 (Mex.).

Ley de responsabilidades de los funcionarios y empleados de la Federación del Distrito Federal y de los altos funcionarios de los Estados [L.R.F.E.F.D.F.A.F.E.] [Act of Responsibility of Officials and Employees of the Federal District and the High State Officials] as amended, Diario Oficial de la Federación [D.O.], 4 de Enero de 1980 (Mex.).

This is a procedure that is followed to remove the constitutional protection granted to public servants.

Daniel Márquez, Función jurídica de control de la administración pública 32-33 (Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas, UNAM, 2005).

Id., at 30.

Secretaría de la Función Pública, 1er. Informe de Labores 2012-2013, “Presentación”, September 1, 2013, p. 8.

Id., at 10.

Id., at 8.

The report is not available on the SFP website. The network was consulted and the figures were obtained from the La Jornada San Luis, available at: http://www.lajornadasanluis.com/2000/11/15/014n1pol.html, accessed on June 14, 2014.

Source: Informe de Labores que presenta el C. Francisco Barrio Terrazas, Secretario de Contraloría y Desarrollo Administrativo, March 31, 2003, available at: http://www.funcionpublica.gob.mx/web/doctos/temas/informes/informes-de-labores-y-de-ejecucion/informe_final.pdf, accessed on June 14, 2014.

Source: Sexto Informe de Labores, 1° de septiembre 2006, available at:http://www.funcionpublica.gob.mx/web/doctos/temas/informes/informes-de-labores-y-de-ejecucion/informeSFP06.pdf, accessed on June 14, 2014.

Source: Quinto Informe de Labores, available at:http://www.funcionpublica.gob.mx/web/doctos/temas/informes/informes-de-labores-y-de-ejecucion/5to_informe_labores_sfp.pdf, accessed on June 14, 2014 (Note: the 2011 report was used because there was no access to the 2012 report).

Transparency International, Global Corruption Barometer, National Results, Mexico, available at: http://www.transparency.org/gcb2013/country/?country=mexico, accessed on June 14, 2014.

Source: Transparency International, Corruption Measurement Tools, Mexico, available at: http://www.transparency.org/country#MEX_DataResearch, accessed on June 14, 2014.

In the 2012 Findings Report, the information is presented under the following heading: As to the scope, the audit simple is estimated at 33.2% of the total revenue and 22.0% of the net expenditure of the Budget for the public sector (See page 19). However, since it does not include the “financial” universe (that is, the total amount of money that was audited or the total “revenues” or “net expenditures”), it is impossible to determine whether this percentage should be considered a measurement of the effectiveness of the work of the ASF.

See Note 22.

Auditoría Superior de la Federación: http://www.asf.gob.mx/uploads/67_Recuperaciones/Opinion_Inf_de_Recuperac_ASF-Mzo14.pdf, (last accessed on June 14, 2014).

Susan Ackerman, Corruption and Government 2 (Cambridge University Press,1999).

Dontella Della Porta and Alberto Vannului, Corrupt Exchanges 16, (Aldine de Gruyter, 1999).

Robert Klitgaard, International Cooperation against corruption, in Finance and Development 4, available athttp://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/1998/03/pdf/klitgaar.pdf, see also: Robert Klitgaard, Controlando la corrupción. Una indagación práctica para el gran problema social de fin de siglo 85 (Sudamericana, 1994).

Shannon O’Neil, Corruption in Mexico, Huffington Post, available athttp://www.huffingtonpost.com/shannon-k-oneil/corruption-in-mexico_b_3616670.html, accessed on October 26, 2013.

Id.

Eduardo Castillo, Mexico Corruption: State Government Scandals Reveal Lack of Disclosure, Enforcement, Huffington Post, available athttp://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/06/26/mexico-corruption-scandals-disclosure_n_3505478.html, accessed on October 26, 2013.

Karla Zabludovsky, Official Corruption in Mexico, Once Rarely Exposed, Is Starting to Come to Light, The New York Times, available athttp://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/24/world/americas/official-corruption-in-mexico-once-rarely-exposed-is-starting-to-come-to-light.html?_r=0

Anne krueger, The Political Economy of the Rent-Seeking Society, The American Economic Review, available athttp://blog.bearing-consulting.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/The.Political.Economy.of_.the_.Rent-Seeking.Society.pdf, accessed on October 26, 2013.

Business Anti-Corruption Portal, Mexico Country Profile, Snapshot of the Mexico Country Profile, http://www.business-anti-corruption.com/country-profiles/the-americas/mexico/snapshot.aspx, (Last accessed on October 26, 2013).

Transparency International, Corruption Perceptions Index 2012, available athttp://cpi.transparency.org/cpi2012/results/, and Bribe Payers Index Report 2011, available athttp://bpi.transparency.org/bpi2011/results/, (Last accessed on October 26, 2013), The last report said: Countries are scored on a scale of 0-10, where a maximum score of 10 corresponds to the view that companies from that country never bribe abroad and a 0 corresponds to the view that they always do.

Nubia Nieto, Political Corruption and Narcotracking in Mexico, available athttp://www2.huberlin.de/transcience/Vol3_Issue2_2012_24_36.pdf, accessed on October 26, 2013.

Jagdish Bhagwati, Economic Freedom: Prosperity and Social Progress, text of the keynote Speech delivered to the Conference on Economic Freedom and Development in Tokyo, June17-18 1999, http://time.dufe.edu.cn/wencong/bhagwati/freedom_tokyo.pdf, accessed on October 26, 2013.

Aguilera, Rodrigo, Corruption: Tackling the Root of Mexico's Most Pervasive Ill, in Huff PostWorld, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/rodrigo-aguilera/mexico-corruption_b_2206967.html, posted November 28, 2012, accessed on October 26, 2013.

Doctor in Law from the National Autonomous University of Mexico and a specialist in administrative law, article published in “The World of the Lawyer” (El Mundo del Abogado).

Amaya Barón, Mario Ismael, Mitos y realidades de la Comisión Nacional Anticorrupción, El mundo del abogado, on February 5, 2013, available at http://elmundodelabogado.com/2013/mitos-y-realidades-de-la-comision-nacional-anticorrupcion/, accessed on October 18, 2013.

Ades, Alberto and Di Tella, Rafael, Rents, Competition, and Corruption, The American Economic Review, 4 (Sep., 1999), 982-993, http://conferences.wcfia.harvard.edu/files/gov2126/files/aerentscorruption.pdf, accessed on October 26, 2013.

The initiative aims at creating the National Anti-Corruption and Control Institute and the Specialized Prosecution for the matter. The institute would be a permanent body with technical, operative, budgetary and decision-making autonomy, with its own legal personality and assets. Its main purpose would be to establish an honest and transparent government through oversight, follow-up, control, inspection, evaluation and sanctions to the public administration, where applicable. Furthermore, the institute would be able to investigate crimes committed by public servants and if necessary proceed to file suit before the corresponding courts. It would also have the power to act on administrative complaints against public servants and sanction those responsible. It would be composed of a plenary, a president of the board, a secretary general, the Control and Administrative Improvement Committee and a Special Prosecutor.