Although several factors have been cited to explain the excessive use of police force, its relation to corruption has yet been little explored. This is a serious omission when dealing with law enforcement agencies in which corrupt practices are both widespread and deeply ingrained, as is the case in Mexico City. On the basis of an analysis of 575 complaints regarding violations of detainees’ right to physical integrity received by the Mexico City Human Rights Commission between 2007 and 2011, many troubling patterns involving the use of excessive police force emerge, including: deeply-rooted and historically-conditioned ways of policing; a form of moral retribution or “punishment” for individuals who resist arrest or challenge authority; poor disciplinary oversight; and lack of professional training (and competence) in resolving conflicts. Above all, the use of excessive force by Mexico City law enforcement agencies is linked to divergent forms of corruption, including extortion, crimes and the misuse of police authority to resolve private matters, among others. In order to address these problems, it is first necessary to recognize their diverse nature and their complex relation to disciplinary structures, accountability and culture.

La relación entre el uso excesivo de la fuerza y la corrupción policial ha sido poco explorada. Esta carencia es grave al estudiar instituciones policiales donde las prácticas de corrupción son extendidas, tal como es el caso en la Ciudad de México (Distrito Federal). A partir del análisis de 575 expedientes de queja por violaciones al derecho a la integridad personal que recibió la Comisión de Derechos Humanos del Distrito Federal entre los años 2007 y 2011, se observan distintos patrones problemáticos. El uso excesivo de la fuerza obedece a motivos diversos: como forma normalizada de realizar el trabajo policial cotidiano, como “castigo” a quien se resiste o falta el respeto a la autoridad, por impericia para resolver una situación conflictiva. Pero también el abuso en el uso de la fuerza se vincula a distintas formas de corrupción policial: extorsiones, delitos, resolución de problemas particulares, etc. Es necesario reconocer la heterogeneidad de los problemas de uso de la fuerza de la policía para pensar medidas con mayor probabilidad de éxito en su contención.

Studies of the excessive use of force by law enforcement agencies have generally ignored the correlation between police brutality and corruption.1 This discrepancy is apparently the result of the different motives seen to be behind each kind of behavior.2 In fact, a careful review of cases involving police corruption and other irregularities show that the two practices clearly overlap.3 One example is the use of threats and excessive force as a means to obtain monetary and other benefits. As a result, there is usually a strong correlation between the deliberate use of excessive force by police agencies and institutional weakness, procedural abuse and rampant corruption.

The history and nature of law enforcement institutions in Mexico and Latin America require a careful analysis of this link. Despite recent legislative reform and infrastructure improvements, law enforcement agencies in Mexico City are still rife with corruption —both operative and administrative—4 as well as recurrent human rights violations.5

This link between corruption and police violence has been brilliantly depicted in Paul Chevigny's classic work, Edge of the Knife: Police violence in the Americas.6 Unlike other cities studied, he concludes that in Mexico City corruption and police violence stem primarily from the corrupt Mexican political system as well as the historical use of law enforcement for political ends. In a review of recommendations made by the Mexico City Human Rights Commission during 1997-2002, I pointed out the existence of three factors that drive police brutality:7 a) as a common way to obtain confessions and/or information; b) as punishment for resisting or defying authority; and c) as a means to gain monetary benefits.

This article applies this matrix to 575 files submitted to the Mexico City Human Rights Commission between 2007 and 2011 concerning violations of the right to physical integrity by Mexico City law enforcement agencies. These files clearly show a significant correlation between corruption and the excessive use of force by Mexico City's diverse police agencies. This is relevant both for academic and policy-making purposes, as the reduction of police brutality can only be achieved by first recognizing its multitudinous forms, causes and conditioning factors.8

This article is organized as follows: (1) the first section summarizes the proposed factors presented in the explanation of police brutality in Mexico City; (2) the second section establishes the link between police corruption and violence, and why this connection is critical to a proper analysis of Mexican law enforcement practices; (3) the third section explains the study's methodology, noting the difficulties posed by currently available information sources and justifying the use of citizens’ complaints before Mexico City's Human Rights Commission; (4) the fourth section analyzes key aspects of these complaints, uncovering several links between corruption and police violence; and (5) the last section discusses how the study's results may be utilized to help transform Mexico City's law enforcement agencies.

IITHEORIES AND RESEARCH INTO THE EXCESSIVE USE OF POLICE FORCEIn any critical study of law enforcement practices, the use of force has always played a central role. Its importance lies in the fact that policing, by its nature, depends on the legitimate use of force.9 This said, the use of force by law enforcement agencies has also been heavily scrutinized because of its major political and social implications. This scrutiny has been particularly acute with regard to police brutality.10

Any study of the use of police force presents several obstacles. If we wish to ascertain how frequently “force” is used by the police, for example, we must first define what types of behavior fall into this category. Although this definition normally takes into account the use of physical force, it may also be broadened to include verbal threats, commands and orders. We may also limit the definition to include solely the use of lethal force (especially with firearms). The broader the definition, the more cases must be analyzed. For this reason, the number and types of situations in which the use of force is studied depends on how “force” is defined.11

As there is no single, universally agreed-upon definition, a more difficult question is how to distinguish between (a) reasonable and necessary use of force; and (b) the deliberate use of excessive force. The International Association of Chiefs of Police has described use of force as the “amount of effort required by police to compel compliance by an unwilling subject.”12 One common yardstick for defining excessive use of force is based on what a highly-qualified policeman would consider “greater than necessary.”13 In other cases, a distinction is made between reasonable and unreasonable force:14 reasonable (or necessary) force is that which must be applied in order to (a) control a suspect if he or she resists arrest; or (b) eliminate an immediate threat. The “reasonableness” of the force is based on the type of resistance and/or degree of immediate threat, either towards persons in the vicinity or the police themselves. Such force must cease when the suspect is subdued and the threat removed.

The only problem with these definitions is that they are too vague to determine prima facie whether the degree of force used in specific situations is “reasonable” or “excessive.”15 Since bias and inherent conflict of interest often prevent law enforcement agencies from realizing credible investigations of police misconduct, the use of excessive force can be evaluated by examining administrative records, judicial files and citizens’ complaints.16

Diverse theories and factors have been used to evaluate the excessive use of police force, each relying on distinct units of analysis. The three most commonly cited approaches are: individual, situational and organizational.17Socio-structural levels are also frequently taken into account.18

At the individual level, the “rotten apples” theory suggests that certain attitudes and psychological profiles of individuals within law enforcement agencies make them more prone to use excessive force than others. This has been confirmed by studies showing that most police brutality cases were instigated by a relatively small number of officers.19 Other studies have shown a correlation between gender and the use of excessive force (female officers are less prone to violence).20 A 2007 study in Criminal Justice and Behavior, “Police Education, Experience and the Use of Force,” found that officers with more experience and education may be less likely to use force. Other case studies suggest that certain training programs and accountability structures can also help diminish police brutality.21

At the situational level, there seems to be a correlation between police brutality and circumstantial factors, including: time and place of the encounter (day vs. night, public vs. private);22 the gravity of the misconduct (serious vs. minor offense); the level of resistance;23 and general respect (or lack thereof) for authority.24 The socioeconomic and/or racial profile of apprehended suspects (in particular their social status) have also been frequently cited.25

If a standoff situation occurs in public, officers often feel compelled to maintain the appearance of authority,26 especially when witnesses are present. Any challenge to the officers’ authority in these circumstances generally provokes the use of strong-arm tactics to prevent a “loss of face.”27 All too often, this involves the use of excessive force.28 It also explains why police departments generally receive low marks for holding officers accountable for abuse of authority. Instead, charges are usually brought against those placed under arrest for having challenged police authority.29

The social (or structural) level addresses general characteristics of the different social groups or spaces of police activity. Based on one theory of social control, societies characterized by social stratification and/or economic inequality often favor police coercion to assure the social dominance of privileged groups.30 Unsurprisingly, those within these privileged sectors are in a much better position to exert their demands. Although members of the underclass are most often victims of police brutality, they generally have little influence over law enforcement policy. A second theory on the socio-structural level, social disorganization theory, hypothesizes that a greater use of excessive force by the police corresponds to a lower level of communal life and informal control.31 Another theory suggests that the level of force used by police is directly proportional to the degree of violence they face in their daily work environment. Based on this line of reasoning, the probability of abuse increases in response to hostile and violent social conditions.32

At the organizational level, several theories emphasize the importance of formal and informal rules in governing police behavior. These case studies suggest that certain training programs and accountability structures can significantly diminish police brutality.33 Other studies emphasize the importance of subculture within law enforcement agencies, which often legitimizes police hostility and the excessive use of force.34

To date, there have been few attempts to connect these disparate perspectives in one integral theory. In this respect, the ideas of Janet Chan,35 based on Pierre Bourdieu's concepts of habitus and field, are those most often cited. From this perspective, the situational and organizational theories are linked to the formation of “habitus” which police bear in their professional work, while the organizational factors, together with the structural ones —taking into account the particular history of each society, the relations between the police and the different social groups— make up the particular “field” that structures and constitutes the practices proper to police work.36

Studies that point to the importance of organizational factors tend to focus on: (a) a subculture of concealment and protection that condones (or even encourages) strong-arm practices as necessary for carrying out police duties, in effect creating a “blue code of silence” among officers that conceal even the most outrageous examples of misconduct; and b) the absence or inefficacy of rules and regulations that may help discourage diverse forms of “bad policing behavior.”

The weakness of organizational mechanisms of control that seek to ensure police accountability also tends to foster corruption, especially in societies where corrupt practices are considered “normal.” This said, there have been few studies on how corruption itself favors the excessive and brutal use of public force.

IIICORRUPTION AND POLICE VIOLENCEAnalyzing the factors above, their impact on fostering excessive use of force by the police passes via the subjectivity of the police officer principally by two types of motivations: the officer's duty, both formal and informal, to “arrest offenders” or “maintain order;” and the morally justified urge to seek retribution against those who “deserve it,” either because they break the law or challenge police authority.37 These justifications, however, ignore the motivation to use force to obtain monetary benefits, either on a personal or institutional level.

From an institutional perspective, the use of excessive force is often rationalized to “combat crime,” protect the public against violence and aggression, and maintain police authority. From a socio-structural perspective, the use of force is justified as a tool for political control. Stated differently, most studies regarding the excessive use of force assume that police officers, whether legally or illegally, seek to prevent crime and uphold public order. In societies characterized by acute inequality, law enforcement is seen as an instrument of control over subordinate groups. Fewer studies exist, however, that regard the excessive use of police force as “predatory,”38 in which extracting monetary benefits become one of the central aims of officers’ daily tasks (without necessarily neglecting their main duty to maintain order, as well as occasionally exert political control).

To better understand the link between corruption and the excessive use of force, it may be useful to distinguish between “predatory corruption” and “strategic corruption.”39 Chevigny describes this difference by describing policemen who are either “bent as a job” or “bent for the job.”40 The first term refers to the most commonly used definition of “corruption:” police officers, availing themselves of their position, act to procure a personal or group benefit.41 This usually takes the form of personal enrichment in exchange for not arresting someone who may otherwise be accused (genuinely or falsely) of a crime; or stealing from suspects under investigation. An even more serious problem is that of overt criminal behavior (such as does not arise from the performance of an official function), committed as a result of privileged information or capacity.

Under the heading of predatory corruption, Mexico City police, especially those in criminal investigation agencies, often use threats, intimidation and physical force to solve the problems of private interests. As described in previous studies, this amounts to police who contract out their services to third-parties.42

The aim of the second pattern (“bent for the job “or “strategic corruption”) is not for personal benefits but in compliance with an institutional “mission” or, stated differently, the orders of commanding officers. Although such practices break formal institutional rules, they follow informal ones that often serve to legitimize them.43 The duties of Mexican public prosecutors make them particularly prone to this kind of behavior, although preventive police forces are by no means exempt. Examples include forced confessions; framing suspects to make them appear guilty of crimes; the excessive or unnecessary use of force; planted evidence; and false declarations or witnesses.44

Normally, personal enrichment accompanied by the use of force is typified as one type of “police corruption;” whereas irregularities in the “use of force” is regarded as a separate and distinct issue.45 For this reason, the motivation behind such irregularities include: (a) a necessity of police work; (b) retribution, either for alleged crimes, resistance or disrespect for authority;46 and (c) legitimate way to control an individual or subdue an imminent threat (cases of unnecessary use of force).47

In summary, four types of motivation explain the excessive use of police force:48

- –

Instrumental motivation for the purpose of obtaining personal and/or group benefits (predatory corruption);

- –

Instrumental motivation for the purpose of obtaining informally valued objectives (strategic corruption);

- –

Moral-expressive motivation to “make authority respected” or “punish those who deserve it;”

- –

Instrumental motivation for obtaining formally valued objectives (unnecessary use of force).

The use of excessive force as described in the section above (individual, situational, organizational and social) has been justified by either: (1) instrumental motivation (to stop criminals and/or maintain order); or (2) retribution. However, the scant attention paid to the relation between corruption and the use of force at an organizational level has moved the first type motivation —using force excessively for personal or group gains— to a secondary position. This typology, of course, is purely analytical, as these categories are not mutually exclusive given that more than one motivation can coexist. I will, however, seek to classify the excessive use of police force as a single predominant type of motivation.

IVMETHODOLOGYStudies of the excessive use of police force have been based mainly on three types of data sources: official registers (criminal investigations, reports of use of force, citizens’ complaints); observations of police behavior; and public opinion surveys. Each source has its strengths and weaknesses. Due to time and financial constraints, observation and public opinion surveys are uncommon, especially in Latin America. With regard to official records, there are still no internal reports issued by Mexican law enforcement agencies of the use of police force. Moreover, criminal investigations into police abuse or torture are extremely rare.

To complicate matters further, criminal sentences for the excessive use of police force in Mexico City is practically non-existent. This failure to make law enforcement agencies accountable for police brutality works as a de facto legitimization of such tactics. Between 2007 and 2012, only 11 cases of torture were successfully prosecuted;49 whereas between 2007 and 2008, there were only 31 cases of abuse of authority (after 2009, there have been no official prosecutions). While both preventive and criminal law enforcement agencies in Mexico City are condemned regularly for serious offenses and exceptionally poor disciplinary oversight, officers are rarely subject to prosecution —much less punishment— for brutality and other types of police misconduct.50

Despite this dearth of official records, a considerable number of cases have been registered over the last twenty years by the Mexico City Human Rights Commission.51 Since its founding in 1993, approximately one fifth of complaints for a wide assortment of human rights violations have been filed against officers of Mexico City's diverse law enforcement agencies.52 These complaints, however, represent only a small percentage of human rights violations by Mexico City police. This said, the large number of complaints filed each year provide access to one of the few sources of information available to discuss an issue of urgent importance.

This study is based on an analysis of citizens’ complaints that involve a Mexico City police officer and at least one violation of the right to physical integrity (a category comprised of several types of excessive force). Since only complete electronic files were made accessible, the study began with records initiated in 2007 and completed in 2011.53 During this period, there were a total number of 1,485 cases. Since a major weakness of studies based on citizen's complaints is the low percentage of substantiation,54 we decided to leave out cases considered by the CDHDF to be unsustainable, or when there were insufficient elements to evaluate.55 In this way, the sum was reduced to 706 files, from which another 18% were eliminated because of inconsistent or missing information. This left a total of 575 complaints for violations of the right to physical integrity, all occurring between 2007 and 2011. In each case, the accused was an officer employed by the Public Security Ministry, or the Criminal Investigation unit of the Mexico City Public Prosecutor's Office.

Each file includes a narrative of the alleged violation, accompanied by the response of law enforcement agencies; and finally the CDHDF's determination whether there was an actual violation. Although these documents were of no interest to me as administrative procedures, they served as a window on the use of excessive use of force by the police.

It should be noted that the nature of these procedures limited, at least in part, the data available for the study. Although the complaints fully describe certain violations (e.g., the right to physical integrity), other alleged transgressions (e.g., extortion) are incomplete. For this reason, cases in which force is linked to corruption may be under-represented. Classification of these complaints is therefore not intended to calculate exact percentages for each type of abuse, but rather to shed light on the varied motivations for police abuse, including the pursuit of monetary gains.

VRESULTSMexico City has a permanent population of 8.8 million inhabitants plus a floating population of about 4 million from neighboring municipalities. It's Preventive Police force, under the SSP, is comprised of 40,000 agents, which include riot control and traffic cops; 15,000 auxiliary police; 15,000 banking and industrial police; and over 3,000 Investigative Agents in the Public Prosecutor's.

In April 2008, Mexico City enacted a law reforming the use of police force, and whose provisions regulate: the detention of individuals; public peace; citizens’ security; and police training and professionalization. In November 2010, regulations for this law were issued that required handbooks on the use of force to be developed by the Public Security Ministry and Public Prosecutor's Office. Subsequent to the period analyzed in this article, three additional regulations were published: an arrest protocol for Investigative Agents (May 7, 2012); a protocol for crowd control (March 25, 2013); and a protocol for the detention of offenders and alleged perpetrators (April 2, 2013).

Nearly 7 of 10 types of violations of the right to physical integrity reported in the 575 cases were for “disproportionate or undue use of force” (68%); followed by “threats and intimidation” (16.3%); “simple aggression” (11.1%); and “cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment” (7.3%). A smaller percentage was for torture (2.7%) and extrajudicial executions (1.9%).56 About 40% of these complaints involved either the Public Security Ministry or Public Prosecutor's Office; 57% involved the SSP; and 3% involved officers from both these agencies.57

Although several aspects of the complaints illuminate the motives behind the use of excessive police force, let's first analyze cases in which corruption played a prominent role.

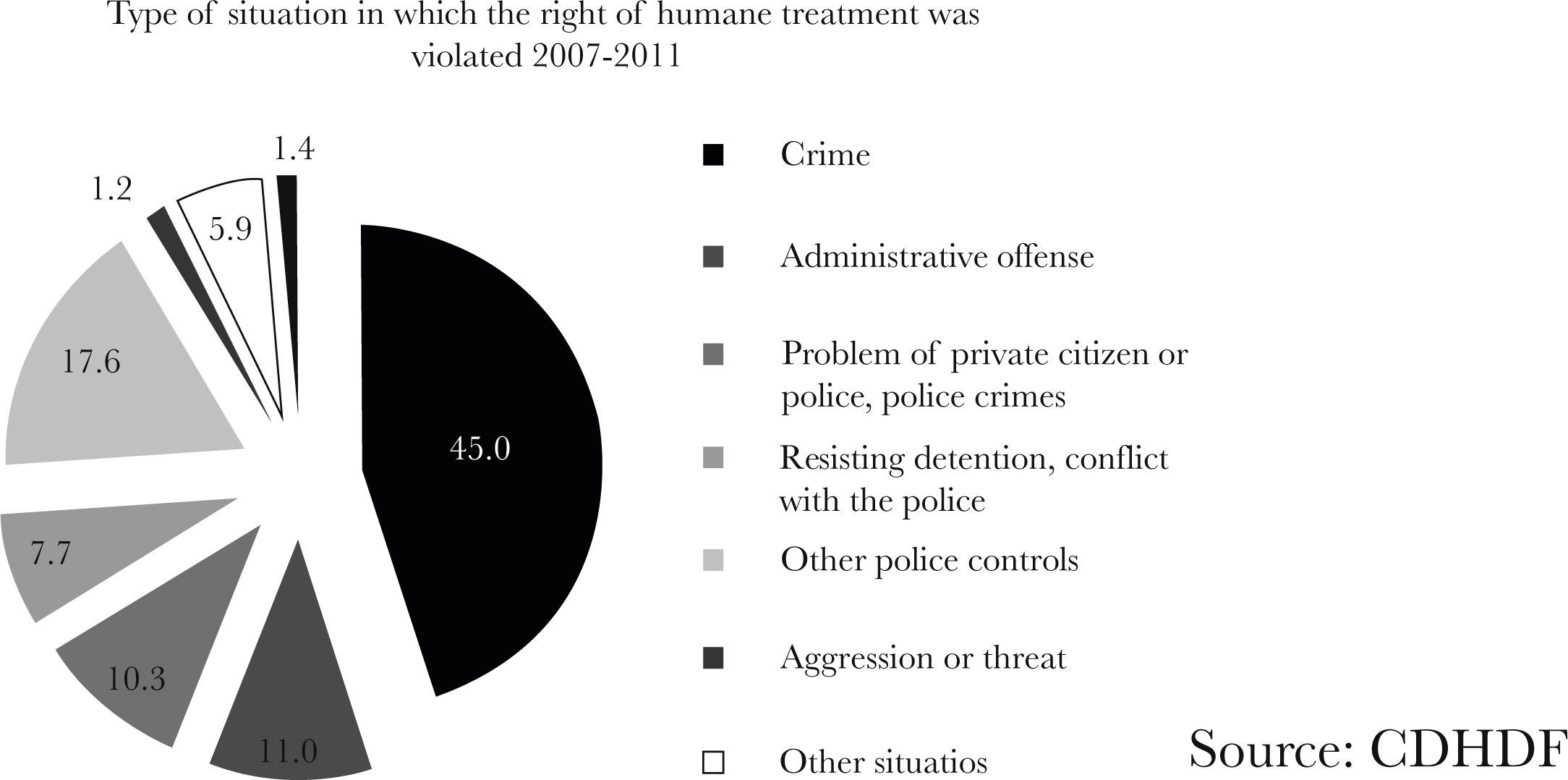

Instrumental motivation to obtain a personal or group benefit (“predatory corruption”)The first element that helps identify the kind of excessive force used by Mexico City's Preventive Police and Investigative Agents involves the “type of situation” (i.e., the nature of the interaction) that gives rise to the complaint (Note: In Fig. 1, both the SSP and PDI of the PGJDF are lumped together).

As one might expect, most situations relate to typical police duties, including arrests for alleged crimes (45%), civil offenses and infractions (11%). Likewise, a large percentage (17.6%) involves other police actions that are lumped together in Figure 1: checks on drivers, control of demonstrations, vehicle spot checks, etc. A third category (“Problem of private citizen or police and police crimes” - 10.3%) deserves special attention, as it involves the kind of predatory corruption mentioned in the section above. This includes: (a) offenses committed by the police that are completely unrelated to their daily duties; and (b) abuse by private third parties (or the police themselves) of official resources and/or police authority to resolve personal or private issues. These “issues” include the recovery of debts, evictions, or intimidation of neighbors embroiled in private disputes. Although these situations generally involve Investigative Agents, they also include violations by Preventive Police to stifle charges against them before a court.

Although the behavior typically associated with corruption involves the solicitation of money in exchange for overlooking criminal behavior —or outright theft from detainees— we believe that the cases classified as “Problem of private citizen or police and police crimes” should also be termed “police corruption”. Based on our analysis, offenses committed directly by the police are realized with public resources and involve the abuse of police authority. For this reason, these acts —as well as police intervention in private matters— should not be considered independent criminal activities but violations that involve direct or indirect personal benefits. In sum, both these situations have the defining features of corruption.

It is important to emphasize two points: (1) if the number of complaints of excessive police force equals or exceeds those provoked by everyday police procedures such as vehicle spot checks or public searches of pedestrians, then corruption is much more widespread than official data indicates; and (2) this is a problem concerning the Mexico City police that has an impact on the systematic patterns of misuse of force by the police.58

In standard interventions such as arrests for crimes or misdemeanors, the police may seek to obtain economic benefits by soliciting money in return for overlooking potential sanctions; or by stealing money or property of the arrested individuals. In some cases, the use of force is a means to apply pressure in order to obtain such benefits; whereas in others, it's a reprisal for an arrestees’ refusal to “pay up.” In many complaints, officers sought to extort and/or steal money or belongings from their victims. This occurred in about a fifth of the encounters (21.3%) initiated by SSP officials in connection with crimes, infractions or spot checks, in which detainees were either robbed of money or belongings or subject to extortion. In the case of arrests and other controls by Investigative Agents, theft and/or extortion accounted for 17.4% of the files reviewed.59

The concurrence of the use of excessive force and corruption does not imply that the officers’ initial motive was to extort money. For this reason, it is rarely easy to establish the temporal sequence of events on the basis of narratives contained in the complaints. Nevertheless, elements exist that seem to corroborate the link between corruption and the use of excessive force. For example, in three of four reported incidents of extortion, the complainant refused to pay what was demanded before force was used against him.

If we combine cases of the use of excessive force reported under “Problems of private citizen or police, police crimes” with violations in which force is connected to or provoked by theft or extortion, the total accounts for 30% of the CDHDF files reviewed. This figure represents a more accurate reflection of police abuse that involves predatory corruption.

Instrumental motivation for obtaining informally valued objectives (strategic corruption)The illegitimate use of force is also commonly used by Mexico City law enforcement agencies to extract confessions and/or information from detained suspects. These are not corrupt practices per se, as there are no overt motives for personal economic benefit. Instead, they constitute “business as usual,” i.e., what law enforcement agencies consider part of their daily duties.60 Stated differently, these are tactics unrelated to “doing justice” but rather routine, “bureaucratic” mechanisms that “culprits” often face when detained by the authorities.61 Not including the cases mentioned above that involve monetary gain, 12% of complainants cited the use of excessive force as a means to obtain a confession or extract information. If we consider only those cases involving either the Public Security Ministry or Public Prosecutor's Office, this amounted to 17.5% of reported complaints. The use of excessive force is thus a “tool” commonly used by Mexico City police to substantiate guilt, similar to planting evidence or presenting false witnesses.62

Grouping together (a) complaints about the “privatization” of police resources (i.e., the use of force to extract rent from the public); and (b) complaints about the use of force to incriminate detained suspects or obtain information, equals aprox. 40% of all cases handled by Mexico City's Public Prosecutor's Office; and 34% of cases involving the Federal Public Security Ministry.

Moral retribution: “respect for authority”So far, this article has examined corrupt law enforcement practices in which illegal objectives are pursued in tandem with official duties, and where the use of force acts as a means to obtain personal and/or group benefits. We also looked at the use of excessive force as a means for performing day-to-day police duties, depending on the functions of each particular agency. To these we must add a third category: the use of excessive force as a reaction to challenges made to the real or symbolic power of police officers.

The theoretical and empirical justification for “punishing” those who “deserve it” (the marginalized, poor, disrespectful and those who resist authority) have been examined in a number of UK, US63 and Latin American64 studies. In this study, several cases seem to involve retribution —the use of police force for moral and/or disciplinary reasons—. Resisting authority at the moment of arrest (e.g., aggressive behavior or attempting to escape) is repaid with police violence when the suspect is finally detained. In numerous cases, a mere insult or show of “disrespect” provoked a disproportionate use of force. In other cases, in which neither resistance nor challenges to authority took place, the suspect is abused simply for having committed a serious crime.

The excessive use of force occurs either at the time an arrest takes place or after the detainee is moved elsewhere. In the latter cases, it is more likely that the mistreatment and/or beatings take the form of “punishment,” as the victim is already under control. In 23.4% of the cases in which Preventive Police were involved, the excessive use of force occurred at a distance from where the initial encounter took place. When Investigative Agents were involved, the percentage was 43.4%. Regarding location, 57.4% of suspects arrested by the Preventive Police were abused in the precinct (a local branch of the Public Prosecutor's Office 42.6% took place inside a patrol car or other vehicle; and 17.4% in some other public location.65 When Investigative Agents were involved, 71.4% of abuse took place in a Public Prosecutor's Office; 41.6% in a patrol car or other vehicle; and 5.2% in some other public area. Many of these cases, as explained above, involved extortion, theft or attempts to secure a confession.

If we leave aside those cases where the main motive was either to extract payment or obtain a confession, the use of excessive force that occurred at a distance from the initial encounter amounted to 15.7% of all cases (13.8% involving Preventive Police, and 19.4% involving Investigative Agents).66

Main motive for obtaining formally valued objectives (unnecessary use of force)The complaints analyzed helped shed light on well-established motives: the extraction of payments, confessions and information, or “punishment” for resisting arrest or showing disrespect for authority. It is likely that the number of cases involving these motives are underrepresented, as not every type of case includes relevant data; e.g., extortion. This said, these cases clearly confirm the presence of diverse patterns linked to the use of excessive force. In the remaining cases (aside from those already mentioned), such force only takes place at the site of arrest and does not seem to involve the extraction of payments or confession. None of these cases are catalogued by the CDHDF as torture, or arbitrary or extrajudicial execution.

It is possible that in these cases the police intended to arrest or subdue an individual but, due to incompetence, lack of training or routine, employed excessive force. Between 2007 and 2011, such cases accounted for 4 out of 10 complaints against Investigative Agents; whereas for the Preventive Police, half the files fell into this category.

In sum, it is fundamental to recognize the diversity of cases involving the use of excessive force and their relation to the dynamics of law enforcement practices, including corruption, deeply-entrenched ways of handling detainees and harsh forms of “punishment” generated in response to the situational demands of police work. As long as the institutional incentives, structures and customs that support such practices are not altered, regulatory changes and improved training cannot be expected to make a significant impact.

VICONCLUSIONSStudies on the excessive use of police force have taken into account individual, situational, organizational, and social factors. Organizational factors include institutional control mechanisms such as training programs and accountability structures, as well as a subculture that legitimizes the use of excessive force in carrying out day-to-day police work. This said, research regarding the relation between corruption and police violence is scarce.

This failure to analyze the link between corruption and police brutality is a serious omission when dealing with law enforcement agencies in which widespread corruption has deep historical roots. Such is the case of Mexico City's Preventive Police and Investigative Agents. To give an account of that part of the problem of excessive use of force in the Distrito Federal that derives from objectives of obtaining rent implies acknowledging the heterogeneity of the phenomenon of police violations of the right to physical integrity and, along with this, the complexity of the responses that would be necessary in order to contain it. Based on an analysis of nearly 600 citizens’ complaints received by the CDHDF between 2007 and 2011, many troubling patterns involving the use of excessive force emerge, including: corruption, a deeply-rooted modus operandi, retribution, incompetence and lack of training, among others.

While the problems generated by the use of excessive force have recently acquired greater political and social importance, the proposals, regulations and institutional changes adopted to reduce it have had, at best, only limited success. Each of these responses have emphasized greater regulation of law enforcement agencies as well as increased training of police officers.67 The main weaknesses of this approach —and the most costly reforms from the point of view of the quotas of power affected within the corporations— include a lack of both disciplinary structures and accountability. A clear reflection of the latter may be seen in the extremely low sanctions currently in place for those found guilty of violating detainees’ right to physical integrity. The inefficacy of these norms act to preserve the widespread practice of corruption and, as a result, the endemic problem of police brutality.

This article forms part of the results of a research project “Police and the use of force in Mexico City (Distrito Federal): patterns of abuse and criteria for action,” carried out under inter-institutional agreement between the Institute for Legal Reesearch of the UNAM and the Mexico City Human Rights Commission. Thanks are due to the Centro de Investigación Aplicada en Derechos Humanos (CIADH) of the CDHDF for all the support and collaboration provided for the project.

Kim Lersch & Tom Mieczkowski, Violent police behavior: Past, present, and future research directions, Vol. 10, Aggression and Violent Behavior, 552, 568, (2005). Philip Stenning et al., Researching the use of force: the background to the international project, Vol. 52, Crime Law & Social Change, 95, 110, (2009).

Sanja Kutnjak, Fallen Blue Knights. Controlling Police Corruption (Oxford University Press, 2005).

For example, for the United States: The City of New York. The Knapp Comisssion. Report on Police Corruption (1973). The City of New York. Comission to Investigate Allegations of Police Corruption and The Anti-Corruption Procedures (1994). Kutnjak,supra note 2.

Arturo Alvarado, The Industrial Organization of Police Work (2008) (unpublished work presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association). Elena Azaola & Miquel Ruiz, Investigadores de Papel. Poder y Derechos Humanos entre la Policía Judicial de la Ciudad de México (Fontamara 2009).

Azaola & Ruiz,supra note 4.Carlos Silva, Policía, Encuentros con la Ciudadanía y Aplicación de la Ley en Ciudad Nezahualcóyotl (Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas, 2011).

Paul Chevigny, The Edge of the Knife. Police Violence in The Americas (The New Press 1995).

Carlos Silva, Police abuse in Mexico City, in Reforming the Administration of Justice in Mexico 175,194 (W.A. Cornelius & D. Shirk (eds.), 2007).

Every time a “scandal” occurs regarding the excessive use of force in Mexico City, there are general calls for improved police training (for the New's Divine nightclub case, see Carlos Silva, Policía, uso de la fuerza y controles sobre la población joven, in Sin Derechos. Exclusión y Discriminación en el México Actual 175, 197 (Institute for Legal Research, UNAM 2014), and the need for specialized protocols (in recent years, many regulations have been enacted regarding the Mexico City police). These measures, however, have been clearly inadequate. Training and protocols do not, in and of themselves, change anything without changes in deeply-entrenched institutional practices (e.g., police accountability).

Egon Bittner, The capacity to use force as the core of the Police Role, in The Police and Society (Victor E. Kappeler (ed.), 2006).

William Geller & Hans Toch, Police Violence. Understanding and Controlling Police Abuse of Force (Yale University Press, 1996).

International research that takes in the whole universe of contacts between police and the public indicates that cases involving the use of force are quite infrequent (see Christopher Birkbeck & Luis Gerardo Gabaldón, La disposición de agentes policiales a usar la fuerza contra el ciudadano, in Violencia, Sociedad y Justicia en América Latina 229, 244 (Roberto Briceño (ed.), 2002), Matthew Durose et al., Contacts Between Police and the Public. Findings from the 2002 National Survey, Bureau of Justice Statistics 2005, available at http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pub/pdf/cpp02.pdf. Durose et al., 2005). In studies of urban environments, the percentage of encounters in which force is used ranges between 1% and 3%. For this reason, many investigations focus on situations in which it is most likely that the use of police force is exercised (especially detentions of suspects of having committed a crime or minor offense). It is, however, necessary to know whether contacts in which force is used are also infrequent in Mexico). The few studies available indicate that the use of police force is fairly common. In a survey carried out in 2005 in the municipality of Nezahualcóyotl, 12% of the population who had contact with the police last year reported either threats or the use of force directed against them. See Silva,supra note 7.

The international principles most commonly referred to are those contained in Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials: U.N. Eighth United Nations Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders, (August 7 to September 7, 1990); and Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials: Gaor 34/169 (December 17, 1979). In these documents three guiding principles for the use of force by police organizations stand out: absolute necessity, rational use, and proportionality, see Geoffrey Alpert & Roger Dunham, Understanding Police Use of Force (Cambridge University Press 2004).

Carl Klockars, A Theory of Excessive Force and Its Control, in Police Violence 1, 22 (William A. Geller & Hans Toch (eds.), 1996).

Geoffrey Alpert & William Smith, How reasonable is the reasonable man: police and excessive force? Vol. 85 No. 2 The Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology 481, 501 (1994).

Within the category of inadequate use of force, a distinction has been made between two types according to the way in which the actor views his own behavior: extralegal and unnecessary force. “Extralegal” force involves the voluntary and conscious use of force that police officers know surpasses established limits. The unnecessary use of force occurs when officers, albeit with good intentions, cannot deal with a situation without recourse to excessive force or to force in general. See James J. Fyfe, The split second syndrome and other determinants of police violence, in Violent Transactions (A. Campbell & J. Gibbs (eds.), 1986).

Kenneth Adams, Measuring the prevalence of police abuse of force, in Police Violence 52, 93 (William Geller & Hans Toch (eds.), 1996).

Robert J. Friedrich, Police Use of Force: Individual, Situations and Organizations, 452 Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 82, 97 (1980). Robert E. Worden, The causes of police brutality: theory and evidence on police use of force, in Police Violence 23, 51(William Geller & Hans Toch (eds.), 1996).

David Jacobs & Robert O’Brien, The Determinants of Deadly Force: A Structural Analysis of Police Violence, Vol. 103 No. 4 American Journal of Sociology 837, 862 (1998). Tim Newburn & Robert Reiner, Policing and the police, in The Oxford Handbook of Criminology (Oxford University Press 2007).

Hans Toch, The violence-prone police officer”, in Police Violence. Understanding and Controlling Police Abuse of Force 62, 80 (William Geller & Hans Toch eds. 1996). Kim Lersch & Tom Mieczkowski, Who are the problem-prone officers? An analysis of citizen complaints, Vol. 15 American Journal of Police 23-44 (1996). Adams, supra note 16.

Sean A. Grenan, Findings on the role of officer gender in violent encounters with citizens, Vol. 15 Journal of Police Science and Administration 78, 85 (1987).

Kim Lersch & Tom Mieczkowski, supra note 1. Brandl et al., Who are the complaint-prone officers? An examination of the relationship between police officers’ attributes, arrest activity, assignment, and citizens’ complaints about excessive force, 29 Journal of Criminal Justice 521, 529 (2001). William Terril & Stephen Mastrofski, Situacional and Officer-Based Determinants of Police Coercion, Vol. 19 No. 2 Justice Quarterly 215, 248 (2002).

Tim Phillips & Phillip Smith, Police violence occasioning citizen complaint. An empirical analysis of time-space dynamics, 40 British Journal of Criminology 480, 496 (2000).

John MacDonald et al., Police Use of Force: Examining the Relationship Between Calls for Service and the Balance of Police Force and Suspect Resistance, Vol. 31 Journal of Criminal Justice 119, 127 (2003).

Robert J. Friedrich supra note 17, Lonn Lanza-Kaduce & Richard G. Greenleaf, Age and Race Deference Reversals: Extending Turk on Police-Citizen Conflict, Vol. 37 No. 2 Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 221, 236 (2000). Robin Shepard Engel, Explaining suspects’ resistance and disrespect toward police, 31 Journal of Criminal Justice 475, 492 (2003).

Situational theories indicate that the police use force to a greater extent against individuals of lower social status (poor or marginalized people, etc.) for a variety of reasons (see Geoffrey Alpert, Police use of deadly force: The Miami experience, in Critical Issues in Policing 480, 495, Roger Dunham & Geoffrey Alpert eds. 1989). Christopher Birkbeck & Luis Gerardo Gabaldón, La disposición de usar la fuerza contra el ciudadano: un estudio de la policía en cuatro ciudades de las Américas, Vol. 2 No. 31 Capítulo Criminológico 33,77 (2003). On the one hand, being regarded as individuals of lesser value render them “deserving” of punishment when committing an offense or showing lack of respect. On the other hand, police officers learn from experience that a greater degree of violence is “appropriate” when dealing with individuals who “do not understand other approaches.” This arises on the basis of what William Ker Muir once called the “paradox of dispossession:” the more difficult it is for the police to “threaten” a person with nonphysical harm (e.g., a legal recourse that may affect their prestige or wallets), the greater the likelihood of physical force (see William Ker Muir Jr., Streetcorner Politicians, The University of Chicago Press 1977). This tendency is reinforced by the diminished likelihood of complaints filed by individuals of lower socioeconomic status. Police also tend to exert greater force against suspects who they label “assholes”, i.e., those with “less to lose” and thus more prone to confrontation (see John Van Maanen, The Asshole, in Policing: A View From the Streets 302, 328, John Van Maanen & Peter Manning (eds.), 1978); or suspects they classify as “symbolic assailants” (Skolnick, Justice without Trial: Law Enforcement in Democratic Society, Macmillan, 1994); i.e., those who speak and behave in ways that reflect violent tendencies (see Jerome Skolnick, Justice Without Trial, New York, Wiley 1994).

Erving Goffman, La presentacion de la persona en la vida cotidiana, (Amorrortu 1971). Geoffrey Alpert & Roger Dunham,supra note 14.

Muir,supra note 25, Penny Green & Tony Ward, State Crimes. Governments, Crime and Corruption, (Pluto Press 2004).

Silva, supra note 7.

Satnam Choongh, Policing the Dross. A social disciplinary model of policing, Vol. 38 No. 4 British Journal of Criminology 623, 634 (1998).

David Jacobs & Robert O’Brien, The Determinants of Deadly Force: A Structural Analysis of Police Violence, Vol. 103 No. 4 American Journal of Sociology 837, 862 (1998). Malcolm Holmes, Minority Threat and Police Brutality: Determinants of Civil Rights Criminal Complaints in U.S. Municipalities, Vol. 38 No. 2 Criminology 343,367 (2000).

Kane, Robert Kane, The Social Ecology of Police Misconduct, Vol. 40 No. 4 Criminology 867, 882 (2002).

William Terrill & Michael D. Reisig, Neighborhood context and police use of force, Vol. 40 No. 3 Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 291, 321 (2003). Tim Newburn & Robert Reiner supra note 18.

James J. Fyfe, Administrative intervention on police shooting discretion: An empirical examination, Vol. 7 Journal of Criminal Justice 309, 323 (1979). Samuel Walker, The New World of Police Accountability (Sage, 2005). Fridell, Lorie Fridell, Use-of-Force Policy, Policy Enforcement and Training, in Critical Issues in Policing: Contemporary Readings 513, 531 (Roger Dunham & Geoffrey Alpert (eds.), 2010).

William Westley, Violence and the Police (MIT Press, 1970). William Terrill et al., Police Culture and Coercion, Vol. 41 No. 4 Criminology 1003, 1034 (2003).

Janet Chan, Changing police culture, in Policing Key Readings 338, 363 (Tim Newburn ed. 2005). Janet Chan, Fair Cop: Learning the Art of Policing (University of Toronto Press, 2003).

Jyoti Belur, Permission to Shoot? Police use of Deadly Force in Democracies (Springer, 2010).

Such punishment allows police to maintain their “image” as an authority in control of areas where they carry out their work. On occasion, the need to “punish” those who behave aggressively or without respect is so acute that it prevails over the need to uphold professional integrity. See Friedrich, supra note 17.

Gerber and Mendelson point out the existence of two law enforcement models: the “functionalist” model, common in developed democracies where police provide services to the public, enforce the law and maintain public order; and the “divided society” model common in authoritarian societies or those with a polarized social structure in which the police protect the interests of elites and repress subordinated groups such as the poor or political opponents. A third model is termed “predatory,” in which “police officers prey on their society by using their positions to extract rents in the form of money, goods, or services from individual members of the public. They apply violence both as a direct means of extracting these rents and in order to satisfy occasional demands by officials to assist in oppressing opposition groups or to give the appearance of solving criminal cases, thereby preserving their access to opportunities for rent extraction” Theodore P. Gerber & Sarah E. Mendelson, Public Experiences of Police Violence and Corruption in Contemporary Russia: A Case of Predatory Policing? Vol. 42 No. 1 Law & Society Review1, 44 (2008).

Maurice Punch, Conduct Unbecoming: The Social Construction of Police Deviance and Control (Tavistock, 1985).

Chevigny,supra note 6, Belur,supra note 36.

Kutnjak,supra note 2.

Beatriz Martínez de Murgía, La Policía en México (Planeta 1998). This kind of practice, while it may or may not represent a direct source of income to the police, does offer benefits to those who “request the service.” Cases also occur where the problem the police set out to solve is a personal problem (and action is taken by police in their capacity as such).

These sorts of behavior cannot be attributed to a lack of police “training” or “professionalism,” since in reality they are not “irregularities” but rather forms of behavior legitimized by the “subculture” of the institution and shared expectations regarding the way in which police work is realized. See Patricio Tudela, Aportes y desafíos de las ciencias sociales a la organización y la actividad policial, Fundación Paz Ciudadana (2011).

In the Distrito Federal, such acts of “strategic corruption” involved in presenting detainees and “framing” them are seen as expedients enabling police to perform tasks expected of them by their commanding officers, the search for truth being a much less important goal.

Kutnjaksupra note 2.

On the basis of research carried out in Venezuela, as well as studies performed in other countries (United States, Argentina), Luis Gerardo Gabaldón distinguishes between two forms of police force: “instrumental” and “expressive.” See Luis Gerardo Gabaldón, Función, fuerza física y rendición de cuentas en la policía latinoamericana. Proposiciones para un nuevo modelo policial, in Seguridad y Violencia: Desafíos para la Ciudadanía 253, 276 (Lucía Dammert & Liza Zúñiga eds. 2007).

Fyfe, supra note 15.

The distinction between motivations is purely theoretical; several may coexist empirically. Nevertheless, an attempt will be made to classify the excessive use of police force on the basis of a predominant type of motivation.

inegi.com.mx. Visited 9/09/2014.

Azaola & Ruiz,supra note 4.

Democratic societies must possess mechanisms for identifying, documenting and containing the problems of police abuse, whatever their dimensions. The development of civil agencies of control has represented one of the most important efforts for finding solutions to such problems.

Citizens’ complaints have been one of the most important sources of information regarding police abuse, Paul Chevigny's study being one of the pioneers. See Paul Chevigny, Police Power: Police Abuses in New York City(Pantheon, 1969).

The collection of information took place during 2013.

Adams, supra note 16.

The causes of conclusion not considered were those marked as “No violation of human rights” and “Insufficient information.” Those included in the universe correspond to “Solved in the course of the proceedings,” “Recommendation,” “Lack of interest” and “Withdrawal of complaint.” The two latter categories are not so much indicators of the weakness of the complaint, as, rather, of the difficulties the complainants and aggrieved parties faced for continuing with the procedures, as well as fear or the intimidations to which they are subjected in order to make them desist.

Because of the selection criteria used, the distribution of the types of violations in the final sample varies with respect to the total number of complaints received by the CDHDF during this period. In particular, it includes a lower percentage of cases involving torture. The percentages should not be taken as representative of the social distribution of the problems of police violation of the right to humane treatment (since cases reported to the CDHDF represent only a minor percentage of actual cases). This said, the sample includes numerous allegations of the use of excessive of force and, as such, a good indication of both its frequency and nature.

Complaints involving police from the Public Security Ministry are divided as follows: 75% involve preventive police; 10% auxiliary police; 9% grenadiers (NOTE: this term is rarely used in English, “riot police” would be better) and Task Force; 5% Banking and Industrial Police; and 1% Traffic Police. Regarding the Mexico City Attorney General's office, 93% of complaints involve the investigative police; and 7%, members of various specialized groups.

The fourth type of situation (7.7%) —classified as “resisting arrest, conflict with the police”— often implies mistrust and fear of police aggression. These are situations where neighbors and/or family members attempt to avoid an arrest or questioning by law enforcement officials (when a patrol car is parked, or a street closed to transit), which subsequently leads to the use of force. When police have a low level of legitimacy, the threshold for conflict is lowered.

These percentages most likely under-represent cases of rent extraction for crimes, misdemeanors or other instances involving the use of excessive force. The results should not be confused with the frequency with which the police seek to gain monetary benefits when making an arrest or enforcing their authority without the use of excessive force.

The existence de incentive payments awarded to Mexico City police for the arrest of individuals suspected of serious crimes blurs the distinction between “predatory” corruption and “strategic” corruption.

Azaola & Ruiz,supra note 4.

In 13.5% of cases involving “arrests for crimes” made by Investigative Agents, police allegedly planted evidence or presented false witnesses – in addition to violating the detainees’ right to humane treatment.

Albert Reiss, Police brutality. Answers to key questions Vol. 5 No. 8 Transactions 10, 19 (1968). Chevigny,supra note 6. Donald Black, The Behavior of Law (Academic Press 1976). Friedrich, supra note 17. Muir,supra note 25. Van Maanen, supra note 25. Steve Herbert , Police culture reconsidered, Vol. 36 No. 2 Criminology 343, 370 (1998). Choongh, supra note 29.

Luis Gerardo Gabaldón & Christopher Birkbeck, Criterios situacionales de funcionarios policiales sobre el uso de la fuerza física”, Vol. 26 No. 2 Capítulo Criminológico99, 132 (1998). Teresa Caldeira, Ciudad de Muros(Gedisa 2007). Birkbeck & Gabaldón, supra note 25. Silva, supra note 7. José Garriga, “Se lo merecen.” Definiciones morales del uso de la fuerza física entre los miembros de la policía bonaerense, No. 32 Cuadernos de Antropología Social 75, 94 (2010).

The percentages exceed 100 because the categories are not mutually exclusive.

The 27 cases catalogued by the CDHDF as torture or arbitrary execution that appear in the cases under study involve punishment, extraction of a confession or payment.

The law regulating the use of force in Mexico City law enforcement agencies (“Ley que regula el uso de la fuerza de los cuerpos de seguridad pública del Distrito Federal”) was enacted in April, 2008. The protocol for police action for crowd control of the capital's Public Security Ministry (“Protocolo de actuación policial de la Secretaría de Seguridad Pública del Distrito Federal para el control de multitudes”) was enacted in March, 2013. The protocol for police action for arrested offenders and suspects (“Protocolo de actuación policial de la Secretaría de Seguridad Pública del Distrito Federal para la detención de infractores y probables responsables”) was enacted in April, 2013.