In the last few years, compassion-based approaches have been integrated into the field of psychology and psychotherapy. In order to evaluate their efficacy – and to explore the relationship between compassion, self-compassion and other psychological processes –, several self-reported instruments have been developed. The objective of this paper is to give a description of the instruments that are available for assessing compassion and self-compassion, with a special focus on those instruments which have been adapted/validated in Spanish. The article begins with a brief definition of compassion, and self-compassion, and thereafter provides a description of the available scales. These scales are reviewed in three different groups: 1) instruments specifically developed to assess compassion/self-compassion that have been adapted/validated in Spanish; 2) other instruments specifically developed to assess compassion/self-compassion (which have not been validated for Spanish speaking populations); and 3) scales that include compassion as one of its components. The science of compassion is an emerging field for which psychometrically robust instruments are needed. Counting on validated measures for Spanish-speaking populations is mandatory for facilitating its use in Spanish-speaking contexts.

En los últimos años ha existido un interés creciente en el campo de la psicología y de la psicoterapia por las prácticas basadas en la compasión. Para poder evaluar la eficacia de las intervenciones basadas en compasión, y para poder explorar la relación entre compasión, autocompasión y otros procesos psicológicos, se han diseñado distintos tipos de instrumentos. El objetivo de este artículo consiste en describir los instrumentos disponibles para evaluar los constructos de compasión, y auto-compasión, haciendo especial énfasis en aquellos instrumentos disponibles en castellano. El artículo comienza con una breve definición de los constructos de compasión, y autocompasión, para posteriormente describir las distintas escalas disponibles. Las escalas se han dividido en 3 grupos: 1) instrumentos diseñados específicamente para medir compasión que disponen adaptaciones/validaciones al castellano; 2) otros instrumentos diseñados específicamente para medir compasión (que no disponen adaptaciones/validaciones al castellano); y 3) instrumentos que miden compasión como uno de sus componentes. El estudio científico de la compasión es un área en plena emergencia, para lo cual es indispensable contar con instrumentos con propiedades psicométricas robustas. Contar con instrumentos validados y adaptados a poblaciones de habla hispana es fundamental para desarrollar este campo en contextos hispanohablantes.

In the last decades the research on psychotherapeutic interventions with Buddhist roots, including mindfulness and compassion, has grown rapidly. While the effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions is quite well-stablished – at least for some particular psychological and medical conditions (Khoury et al., 2013) – the research on the effects of compassion-based practices is still at its infancy.

Meanwhile some authors see compassion from a trait perspective (e.g., Goetz, Keltner, & Simon-Thomas, 2010), the rationale behind compassion-based interventions is that compassion can be developed and enhanced through practice. In a recent review, Kirby (Kirby, 2016) identifies at least six compassion-based programs that differ in their degree of empirical evidence. These programs are: Compassion Focused Therapy (Gilbert & Procter, 2006), Mindful Self-Compassion Training (Germer & Neff, 2013), the Compassion Cultivation Training (Jazaieri et al., 2013), Cognitively Based Compassion Training (Ozawa-de Silva & Dodson-Lavelle, 2011), Cultivating Emotional Balance and Compassion (Kemeny et al., 2012) and Loving Kindness Meditations (Hofmann, Grossman, & Hinton, 2011). Compassion-based programs have been applied across a wide range of populations including healthy-individuals (Germer & Neff, 2013), subjects with high shame and self-criticism, anxiety and depressive symptoms (Gilbert, McEwan, Irons, Bhundia, Christie, Broomhead, & Rockliff, 2010; Gilbert & Procter, 2006), and individuals with personality disorders (Feliu-Soler et al., 2016; Soler et al., 2015).

Despite the enthusiasm of clinicians and researchers, there is lack of consensus on the definition of compassion, which is also reflected in the measurement tools that are currently available. The present article constitutes a synthesis of a larger chapter on compassions measures published elsewhere (Soler, 2016). Here, we provide a brief review the constructs of compassion and self-compassion; and we present an overview of the most used instruments for assessing them, making a special emphasis on those which have been adapted and validated for Spanish-speaking populations.

Defining compassion and self-compassionThe term “compassion” derives from the Latin word “compati”, meaning “to suffer with” (Strauss et al., 2016). Compassion is a fundamental aspect in Buddhist Psychology, not only entailing being in contact with suffering, but also involving a profound commitment to relieve this suffering (Lama, 1995; Neff, 2003).

From an evolutionary perspective, Gilbert (2010) proposed that compassion is rooted in our biological capacity of sensitivity, sympathy, empathy, motivation/caring, distress tolerance and non-judgment, and for him, these are the six attributes of compassion. The first one (i.e. sensitivity), refers to the capacity of being responsive to the emotions of others and to being able to perceive others need for care. “Sympathy” is defined as showing concern for the other person's suffering and “empathy” refers to the ability of putting yourself in other's shoes. “Motivation” is needed to act or response toward the suffering of others. Finally, distress tolerance and non-judgment are relevant as they emphasized that compassion is about helping others without over-identifying ourselves with their suffering (for which distress tolerance is needed) and without judging them, as we can feel compassion toward someone we dislike.

Compassion can not only be directed toward our loved-ones, but also to strangers and ultimately, to all human kind. Self-compassion is understood as the act of transferring these attitudes toward others, toward oneself, which, for many individuals is very hard (Jazaieri et al., 2013). Self-compassion implies not to being judgmental toward oneself (on a cognitive level), and also being able to feel and connect with our own suffering (on an emotional level). For Germer (2011) self-compassion means taking care of oneself as we would do for a loved one. From a Buddhist perspective, Neff (2003) conceptualizes self-compassion with three main components: kindness, common humanity and mindfulness. Neff proposed the notion of “common humanity”, which means that all human beings are united by the experience of suffering. As the Lama points out, all humankind is united in the desire of being free of suffering (Lama, 1984, 2002). The concept of “common humanity”, is similar to the notion of interconnectedness (Pommier, 2010), which highlights that individuality and separation are false beliefs (Salzberg, 1995; Wayment & O’Mara, 2008). For some authors, this sense of interconnection is what frequently motivates compassion and compassionate behaviors (Salzberg, 1997; Wayment & O’Mara, 2008). In contrast, the absence of common humanity would drive someone to isolation and to the denial of others’ suffering. As a consequence of this, there is a barrier between “us” and “them”, (Neff, 2012): when we identify ourselves as being part of one group (us), there is an implicit separation with others (them). Finally, the third component of self-compassion is mindfulness. According to Neff, in the context of self-compassion mindfulness is close to decentering (Fresco et al., 2007; Soler et al., 2014), as mindfulness refers to the capacity of feeling painful emotions and thoughts without over-identifying with them (Neff, 2012).

Interestingly, there is an ongoing debate in regard to whether compassion and self-compassion should be considered different constructs (Strauss et al., 2016). From a Buddhist point of view, this separation between others and the self is fake, however, research has demonstrated that the correlation between these two constructs (compassion and self-compassion) is rather weak (Neff & Pommier, 2013; Pommier, 2010).

Strauss and colleagues (Strauss et al., 2016), hypothesize that this lack of association could be due to the definition of these constructs, the limitations of current measures, or both.

In a recent review of the compassion construct, Strauss et al. (2016) proposed an operational definition of compassion and self-compassion considering a wide-range of definitions from Buddhist and Western psychological perspectives. They defined compassion as “a cognitive, affective, and behavioral process consisting of the following five elements that refer to both self and other-compassion: 1) Recognizing suffering; 2) Understanding the universality of suffering in human experience; 3) Feeling empathy for the person suffering and connecting with the distress (emotional resonance); 4) Tolerating uncomfortable feelings aroused in response to the suffering person (e.g. distress, anger, fear) so remaining open to and accepting of the person suffering; and 5) Motivation to act/acting to alleviate suffering.” (Strauss et al., 2016, pp. 19).

The assessment of compassion and self-compassionIn recent years, compassion-based interventions had emerged in the field of scientific psychology, motiving the research in regard to their effects and mechanisms. Together with this clinical interest, tools for assessing compassion, self-compassion and other related constructs have also been developed. Next, we will give a description of the tools that are available for assessing compassion, and self-compassion, focusing on those available in Spanish. In order to classify the existing instruments, we propose three different categories: 1) instruments that were specially developed to assess compassion or self-compassion that have Spanish validations/adaptations; 2) other instruments that assessed compassion or self-compassion (but have not been validated in Spanish-speaking populations), and 3) instruments that include compassion as one of their components (which have not been validated in Spanish).

Instruments developed to assess compassion and self-compassion with Spanish validations/adaptationsCurrently, there are seven questionnaires specifically designed to assess compassion; but only three of them have been translated and validated into Spanish.

Self-Compassion Scale (SCS; Neff, 2003)The SCS developed by Neff (2003), was the first tool in this field. It was originally supposed to be a three-factor scale, but during its development, the authors realized that it should have six factors: the three main factors of compassion and their respective opposite constructs: kindness and self-judgment, common humanity and isolation, and mindfulness and over-identification. The SCS has 26 items, and each item is answered through a five-point Likert scale (0 being “nearly never” and 4 being “nearly always”). It offers both, a separate score of each component and a total score.

The SCS has adequate psychometric properties: high internal consistency [Cronbach's alpha=0.94 (Neff, Rude, & Kirkpatrick, 2007)] and good test–retest reliability (r=0.93; Neff, 2003). It demonstrated convergent validity with social connectedness and emotional intelligence, and divergent validity with self-criticism, depression, social desirability, narcissism, anxiety and rumination (Neff, 2003). In addition, several studies demonstrate good predictive validity, with positive correlations between self-compassion and mental health signs, such as lower depression and anxiety, and high happiness, optimism and life satisfaction (Neff & Vonk, 2009).

In 2014, Garcia-Campayo and colleagues validated a Spanish version of the SCS, supporting its six-factor structure and finding adequate internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha≥0.86), test–retest reliability (r=0.92), good convergent validity (high correlation with the mindfulness scale Mindful Attention Awareness Scale), and high discriminant validity (with depression, anxiety and other psychopathological self-reports). Two other scales have come from the SCS: the Self-Compassion Scale–Short Form (Raes, Pommier, Neff, & Van Gucht, 2011) and the Compassion Scale (Pommier, 2010).

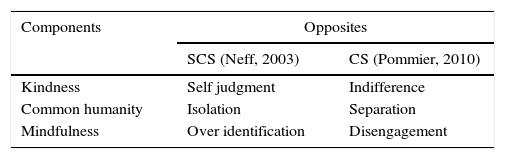

Compassion Scale (CS; Pommier, 2010)The Compassion Scale (Pommier, 2010) was based on Neff's Self Compassion Scale (Neff, 2003). The author wanted to translate the theoretical structure of compassion toward oneself (self-compassion) to compassion toward others. So even though there is some overlapping between the SCS and the CS, because they have the same three main components (kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness), they differ in their opposites. A detailed description of each factor and its opposite is presented in Table 1. In the CS, the opposite of kindness is indifference, a lack of common humanity is separation, and, finally, the opposite of mindfulness is disengagement.

Factors of the Self – Compassion Scale and the Compassion Scale.

| Components | Opposites | |

|---|---|---|

| SCS (Neff, 2003) | CS (Pommier, 2010) | |

| Kindness | Self judgment | Indifference |

| Common humanity | Isolation | Separation |

| Mindfulness | Over identification | Disengagement |

Note. SCS=Self-Compassion Scale. CS=Compassion Scale.

In this scale, items have to be rated on a five–point response scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The proposed six-factor structure was assured by the CFA, and a higher order factor of compassion explained the inter-correlations between the six factors. The CS shows discriminant validity with social desirability, suggesting that the scale is not influenced by socially desirable responding, and convergent validity with compassionate love, social connectedness, mindfulness, wisdom and empathy (Pommier, 2010). Surprisingly, the scale was not significantly correlated with Neff's SCS, which would be expected considering that the CS derives from the SCS.

Recently, Brito (2014) developed a Spanish version of CS, which demonstrated appropriate construct validity and internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha=0.89).

Self-Compassion Scale Short Form (SCS-SF; Raes et al., 2011)In 2011, Raes and his team developed a shorter version of the SCS, the Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form (SCS-SF), with only 12 items. The SCS-SF demonstrated adequate internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha≥0.86) and a robust correlation with the SCS-Long form (r≥0.97; Raes et al., 2011). A Spanish version of the SCS-SF has also been developed (Garcia-Campayo et al., 2014), obtaining appropriate psychometric properties: Cronbach's alpha of 0.85, test–retest reliability of 0.89 and high correlations with the long form and its subscales. The authors recommend using the short form when time is lacking or for obtaining a representative punctuation of compassion. However, if particular information on every compassion dimension is needed, the long form is recommended.

Other instruments developed to assess compassion or self-compassionThe Compassion Scale (CS-M; Martins, Nicholas, Shaheen, Jones, & Norris, 2013)This 10-item-self-reported scale measures five facets of compassion: generosity, hospitality, objectivity, and tolerance across social networks and relationships. The aim of the authors was to create a measure that could reflect changes in compassion due to training. Items were generated by academics and experts on the field. The scale assesses practical acts of compassion such as giving financial support to others or using your free time to help others, and therefore, only actions for alleviate other's suffering are measured.

Compassionate Love Scale (CLS; Sprecher & Fehr, 2005)The CLS is an instrument designed by Sprecher and Fehr (2005) to assess compassionate love. They define compassionate love as an attitude toward others – either close ones or strangers – which entails feelings, cognitions, and behaviors focused on care, concern, tenderness, and an orientation toward supporting, helping, and understanding others, particularly when they are suffering or in need (Sprecher & Fehr, 2005). Even though Sprecher and Fehr (2005) considered naming this construct as altruistic love or compassion, they decided to use the term “compassionate love” to emphasize the emotional and transcendental aspects of compassion. The notion of “compassionate love”, presented by Sprecher and Fehr (2005), and the notion of self-compassion, described by Neff, refer to kindness and the desire to relieve suffering. However, they have different roots, as the notion of the compassionate love construct does not come from Buddhist principles. Due to this, compassionate love does not include components such as mindfulness or common humanity.

The CLS has two versions, one assessing compassion toward others (family and close friends) and a second one assessing compassion toward all humankind (strangers, peripheral ties, or all humanity). The scale has 21 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale. Both versions of the CLS have shown solid properties of reliability, with high internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha=0.95). Positive correlations have been found between the CLS and empathy (r=0.50 and r=0.68 for compassion toward others and compassion toward all humankind, respectively); helpfulness (r=0.23 and r=0.32); voluntarism (r=0.19 and r=0.25); religiosity (r=0.22 and r=0.26) and prosocial behavior (r=0.51 and r=0.27; Sprecher & Fehr, 2005).

Santa Clara Brief Compassion Scale (SCBCS; Hwang, Plante, & Lackey, 2008)In order to obtain a useful instrument for epidemiological studies, in 2008, Hwang and colleagues developed a shortened form of the Compassionate Love Scale (CLS; Sprecher & Fehr, 2005), called the Santa Clara Brief Compassion Scale (SCBCS; Hwang et al., 2008). The SCBCS contains only five items, and unlike the CLS – which contains three factors –, the SCBCS has a unifactorial structure. A correlation of 0.95 has been reported between the SCBS and the CLS. In addition, positive correlations were found between the SCBCS and vocational identity, faith, and empathy (Hwang et al., 2008).

Relational compassion scale (RCS; Hacker, 2008)This is a 16-item self-reported scale, comprising 4 sub-scales: 1) compassion for others, 2) self-compassion, 3) beliefs about how compassionate other people are to each other, 4) beliefs about how compassionate other people are to them. This four-factor structure was supported in confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

Instruments that include compassion as one of its componentsApart from the previously mentioned questionnaires, there are also some instruments that assessed compassion as one of their components. The main characteristics of these instruments are listed below.

Dispositional Positive Emotion Scale (DPES; Shiota, Keltner, & John, 2006)The authors of the DPES propose a model of six basic positive emotions: joy, contentment, pride, love, compassion, amusement and awe. According to this model, compassion is similar to sympathy and is characterized as concern for others’ well-being and as the behavior of helping people in need. The compassion subscale of the DPES comprises five items designed to measure a dispositional tendency to feel compassion toward people in general. The DPES has 38 items grouped into seven subscales, one for each emotion. Participants have to rate their answers on a seven-point Likert scale. The questionnaire showed a suitable factorial structure and a suitable internal consistency (with Cronbach's alpha of 0.82, 0.92, 0.80, 0.80, 0.80, 0.75 and 0.78 for each scale, respectively; Shiota et al., 2006).

Self-Other Four Immeasurables (SOFI; Kraus & Sears, 2009)The SOFI was created to measure applications of the four main qualities of Buddhist teachings: loving kindness, compassion, joy, and acceptance toward both the self and others. The SOFI is a 16 items instrument, rated in a five-point Likert scale. Items are grouped into four subscales: positive qualities toward oneself, positive qualities toward others, negative qualities toward oneself and negative qualities toward others. All scales have high internal consistency with values between 0.80 and 0.86. They showed appropriate construct validity, and convergent and discriminant validity with high correlations with the SCS (Kraus & Sears, 2009), as well as with other scales such as the PANAS (Positive and Negative Affect Scale; PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) and the CAMS-R (Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale; Feldman, Hayes, Kumar, Greeson, & Laurenceau, 2004). The SOFI has been used in research on mindfulness, and positive and social psychology.

Interestingly, the study of compassion has encouraged the development of other instruments for measuring similar constructs as “fears of compassion” accounted in the Fears of Compassion Scale (FCS; Gilbert, McEwan, Gibbons, Chotai, Duarte, & Matos, 2012) or to elucidate whether kindness and compassionate behaviors are due to submissive behaviors (such as a desire to please others and not being rejected), or due to genuine compassionate feelings (Submissive Compassion Scale Catarino; Catarino, Gilbert, McEwan, & Baião, 2014). Unfortunately, Spanish versions of these two instruments are not available yet.

Although this article focuses on measures that were developed to assess compassion and self-compassion, we would like to mention the existence of other measures that assess constructs like social connectedness (Lee and Robbins, 1995), happiness (Hervas & Vázquez, 2013) and sympathy (Lee, 2009), which are – at least theoretically – related to compassion.

DiscussionCompassion and compassion-based programs are receiving increasing attention of clinical and social psychology researchers. Compassion is a complex construct and several definitions of the construct co-exist. However, as it has been stated in a recent work, compassion would be operationalized as a set of processes which encompass cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses to suffering (Strauss et al., 2016), including the recognition of self- or others suffering, understanding it as a part of a common nature, feeling empathy for those who experiencing it, and the willingness to alleviate it.

Interestingly, and although there is a positive relationship between the components of compassion proposed by Neff (2003; i.e., mindfulness, common humanity and kindness), these associations are as strong as the ones established between these three components and other constructs including social connectedness, emotional intelligence, empathy or wisdom (Soler, 2016). Therefore, developing more accurate and operational definitions of the construct is still needed.

Many instruments have been developed to assess compassion and self-compassion but there is still a paucity of psychometric sound measures, particularly developed or adapted for Spanish-speaking populations. Among all the instruments here reviewed (as it was also recently stated in a systematic review; Strauss et al., 2016), Neff's (2003) Self-Compassion Scale and Hacker's (2008) Relational Compassion Scale are probably the most psychometrically robust instruments. Remarkably, there is only three tools validated and adapted to Spanish-speaking populations at this stage: the Compassion Scale (CS; Pommier, 2010), Neff's Self-Compassion Scale (SCS; Neff, 2003) and the Compassion Scale short form originally developed by Raes (SCS-SF; Raes et al., 2011). More research is warranted in order to develop and test psychometric properties of new scales with a more comprehensive definition of compassion, and an extra effort must be made to make them also available for its use in Spanish-speaking settings.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

This study was funded by a grant for research projects on health from ISCIII (PI13/00134) and co-financed with European Union ERDF funds.