Compassionate patient relationships can be deeply rewarding, but continuous exposure to emotionally charged situations can also tax clinicians’ emotional resources and lead to exhaustion and burnout. A better understanding of factors that relate to clinicians’ ability to manage the emotional demands of the profession is needed. Hence, this study examined the relationships between emotional intelligence, empathy, and job-related compassion and burnout in 92 direct-care registered nurses in the United States. Results showed that whereas higher levels of emotional intelligence, empathy for others’ positive emotions, and empathy for others’ negative emotions were associated with greater compassion satisfaction, only higher levels of emotional intelligence and empathy for positive emotions were associated with reduced fatigue and burnout. The results have implications for clinicians as they provide foundational information to help determine appropriate strategies, supports, and solutions to reduce compassion fatigue and burnout while increasing compassion satisfaction.

Las relaciones compasivas hacia los pacientes pueden ser muy gratificantes, pero la exposición continua a situaciones con una carga emotiva también puede hipotecar los recursos emocionales de los profesionales clínicos y provocar agotamiento y desgaste profesional. Es necesario una mejor comprensión de los factores que se relacionan con la capacidad de los profesionales clínicos para manejar las exigencias emocionales de la profesión. Por ello, este estudio analizó las relaciones entre inteligencia emocional, empatía y compasión relacionada con el trabajo y desgaste profesionales en 92 enfermeras estadounidenses que prestaban cuidados directos. Los resultados mostraron que, mientras que los niveles más altos de inteligencia emocional, la empatía por las emociones positivas de los demás y la empatía por las emociones negativas de los demás estaban relacionadas con mayor satisfacción de la compasión, solo altos niveles de inteligencia emocional y empatía por las emociones positivas estaban relacionadas con menor cansancio y desgaste profesional. Los resultados conllevan implicaciones para los profesionales clínicos ya que proporcionan información básica para tratar de establecer las estrategias, apoyos y soluciones apropiadas para reducir el cansancio que comporta la compasión y el desgaste profesional mientras aumenta la satisfacción de la compasión.

Compassion among clinicians has become a priority in the healthcare industry. This is partly related to the fact that clinicians are under tremendous pressure to produce specific patient outcomes. The pressure to obtain positive outcomes can take clinicians’ attention away from compassionate care. Clinicians are focused on completing tasks and paperwork that may result in difficulty connecting compassionately with the patient (Barratt, 2017). Most clinicians enter the profession inspired to provide excellent, compassionate care. Once engaged in practice, however, clinicians are faced with the complex emotional demands associated with providing patient care. This means they must respond to multiple emotional experiences every workday (Cherry, Fletcher, O'Sullivan, & Dornan, 2014). For example, clinicians must attend to the emotional responses of their patients and the healthcare team as well as attend to their own emotional reactions. Compassion and effective emotional abilities are critical skills given the need to promote rapport and trust in interactions. These abilities in turn can lead to positive patient and professional relationships as well as personal and professional satisfaction (Cherry et al., 2014). However, compassionate patient relationships can also all too often drain clinicians’ resources and negatively impact their health and well-being. The continuous exposure to emotionally charged situations can lead to emotional exhaustion and burnout.

Burnout is a critical issue for clinicians in the United States and globally (Gregory, 2015). The prevalence rates for burnout out and compassion fatigue are high for physicians, nurses, social workers, and allied health professionals (Emanuel, Ferris, von Gunten, & von Roenn, 2011). The concern about physician distress, burnout, and well-being has been highlighted in the literature (Shanafelt et al., 2012; Shanafelt, Sloan, & Habermann, 2003). Unfortunately, physicians have demonstrated a higher prevalence and a significantly greater risk for professional burnout compared with the general population (Shanafelt et al., 2012). Nurses have also been negatively impacted by burnout. For example, a recent study by Potter et al. (2010) found that 44% of inpatient nurses and 33% of outpatient nurses were at high risk for burnout. In addition, approximately 17.5 percent of new nurses leave their jobs within the first year (Kovner, Brewer, Fatehi, & Jun, 2014). Burnout has implications for the emotional and physical health of clinicians (Henry, 2014). Clinicians experiencing burnout symptoms may be at greater risk of committing medical errors, and may have interactions with patients that result in dissatisfaction with care (McClure, 2013). Burnout can also influence organizational costs, outcomes, and mortality (Aiken, Clark, Sloane, Sochalski, & Silber, 2002). The healthcare industry cannot afford to lose clinicians to burnout given the projected shortages of physicians and nurses. Hence, it is imperative to have a better understanding of the factors related to compassion fatigue and burnout. Furthermore, additional knowledge regarding the factors that relate to clinicians’ ability to manage the emotional demands of the profession is needed. Therefore, the present study focuses on how emotional intelligence and empathy relate to clinicians’ (specifically nurses’) compassion satisfaction/fatigue and burnout.

Emotional intelligenceThe concept of emotional intelligence was first discussed in the literature in 1990 by Salovey and Mayer. However, it was not until 1995 with the popular press publication of Goleman's book Emotional Intelligence that the concept gained the public's interest. Although emotional intelligence is conceptualized and measured in a variety of ways in the literature, the present research focused on emotional intelligence as a standard intelligence and a mental ability to work with emotional information. In other words, emotional intelligence is viewed in a similar fashion to general intelligence or IQ. This study utilized the Mayer-Salovey four branch model, which theorizes that emotional intelligence is an ability to reason with and about emotions that allows an individual to more fully comprehend and adjust to the individual circumstances of a situation (Mayer & Salovey, 1997). The four branch model involves the ability to: (a) correctly perceive emotions in faces, body language, artworks, and other stimuli; (b) use emotions to assist thinking and functioning; (c) understand the reason for emotions and how they change over time; and (d) successfully manage and regulate emotions of oneself and of others in constructive ways (Caruso, Bhalerao, & Karve, 2016).

The four branch model was utilized because it is associated with an ability-based measurement of emotional intelligence, the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT). Many other measures of emotional intelligence rely exclusively on self-report. Although self-report measures provide information on how respondents view their own emotional skills, they are limited in that people may either be unable to accurately assess their own emotional intelligence or may possess unrealistically positive beliefs about their emotional intelligence. An ability based measure addresses these problems by measuring emotional intelligence in an objective and performance-based manner. As an analogy, people often report they are excellent drivers, but ability based road tests reveal a great deal of variability in people's actual driving abilities. The MSCEIT provides such an ability based measure for emotional intelligence.

Linking emotional intelligence and empathyAmong other things, emotional intelligence can help clinicians to empathize with the patients they care for. Empathy, “an affective response that stems from the apprehension or comprehension of another's emotional state or condition, and which is identical or very similar to what the other person is feeling or would be expected to feel” (Eisenberg & Fabes, 1998, p. 702), has been shown to enhance the therapeutic effectiveness of the clinician-patient relationship (Ioannidou & Konstantikaki, 2008). Emotional intelligence is a basis for empathy and caring, as individuals need to appraise others’ emotions in order to develop those abilities (King, Mara, & DeCicco, 2012; Martos, Lopez-Zafra, Pulido-Martos, & Augusto, 2013; Shanta & Gargiulo, 2014). Emotional intelligence serves as a foundation for empathy as it helps people to: (a) appreciate what is truly worrying other individuals, (b) understand oneself and one's own emotions, (c) remain interested in understanding another individual, (d) effectively communicate, even while giving undesirable messages, and (e) develop trusting and rewarding relationships, solve problems, think creatively, and resolve disagreements (Lanciano & Curci, 2015).

Importantly, although some past research has examined relations between emotional intelligence and empathy as well as personal and professional outcomes among clinicians (Faye et al., 2011), this work has largely focused on empathy for others’ negative emotions (e.g., pain, sadness, anxiety). This focus is logical especially in healthcare settings where clinicians are likely to encounter individuals struggling with negative emotions. In such settings, the extent to which clinicians “feel along with” such negative emotions is likely to be quite consequential. For example, too little connection with a patient's suffering might result in a lack of caring, whereas too much connection with the patient's suffering might result in empathic over-arousal and, eventually, burnout.

However, very little work has looked at empathy for others’ positive emotions (e.g., optimism, excitement, hopefulness). Building on recent work demonstrating that empathy for others’ negative emotions and empathy for others’ positive emotions are distinct from one another (Andreychik & Migliaccio, 2015; Morelli, Lieberman, & Zaki, 2015), it can be argued that such positive empathy may have a beneficial effect for clinicians. For example, clinicians who are particularly likely to connect with their patients’ positive emotions (e.g., hopefulness, optimism) seem likely to draw greater enjoyment from the experience of emotional connection, which may help to buffer the effects of other job-related stresses and, perhaps, make them better able to effectively empathize with the negative emotions that their patients will inevitably experience.

Linking emotional intelligence and empathy with compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnoutBased on the logic outlined above, it is reasonable to assume that both emotional intelligence and empathy might be associated with the specific constructs of compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout. Compassion satisfaction is defined as the pleasure clinicians receive from helping patients (Stamm, 2010). Continually coping with the emotional and physical needs of others can be draining and lead to compassion fatigue. Compassion fatigue is conceptualized as the negative consequence of working with patients in combination with a deep, personal, empathetic orientation (Abendroth, 2011). Burnout is defined as a condition of emotional exhaustion, hopelessness, and decreased ability to perform job duties effectively that can occur among clinicians (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001). Burnout is also considered to be one component of the negative consequence of caring known as compassion fatigue (Stamm, 2010).

Some studies have described a relationship between compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue in clinicians across various specialties (Boamah & Laschinger, 2015; Hinderer et al., 2014; Hunsaker, Chen, Maughan, & Heaston, 2015; Kelly, Runge, & Spencer, 2015; Smart et al., 2014).

Other studies have examined the relationship of emotional intelligence and compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout (Karimi, Leggar, Donahue, Farrell, & Couper, 2013; Kaur, Sambasivan, & Kumar, 2013). However, further research is needed to examine if emotional intelligence and empathy are associated with compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout. In addition, this research goes beyond existing work examining the role(s) of empathy in healthcare settings by focusing on empathy for patients’ positive emotions in addition to empathy for patients’ negative emotions. With the emotional demands that the healthcare environment places on clinicians, a better understanding regarding the associations among these factors is needed. Such information may ultimately assist in identifying strategies that reduce the negative consequences of working in the caring professions. This topic is of interest to clinicians given the potential implication for the quality and safety of patient care as well as the retention of clinicians who might otherwise leave the profession given burnout and compassion fatigue. Hence, the purpose of this study was to examine how emotional intelligence and positive and negative empathy are related to compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout.

MethodThis cross-sectional study used a descriptive, correlational design. The target population was working nurses throughout the United States. Inclusion criteria were: (a) work at least 8h a week in a healthcare environment, (b) interact directly with patients at least 8h per week, and (c) have at least 1 year of experience in healthcare. Approval from the university's Institutional Review Board was obtained prior to data collection.

A description of the study was posted to an online recruitment site (Mechanical Turk). Subjects who met eligibility requirements were directed to an informed consent and then to the surveys. The study remained open until a sample of 100 participants was reached, based on a power computation (Cohen, 1992) conducted on gPower 3.0.5 (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007) indicating that 82 participants were needed based on alpha=.05, effect size moderate (.3), and power equal to .80. Participants were paid $4.

InstrumentsEmotional intelligenceEmotional intelligence was measured by the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT), which is an ability-based measure of emotional intelligence consisting of 141 items measuring four branches of emotional intelligence: perceiving emotions, using emotions to facilitate thought, understanding emotions, and managing emotions (Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2002). The total score provides an overall index of the respondent's emotional intelligence. Split-half reliability coefficients for the four branches range from r=.80 to .91, and for the entire test r=.91 (Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2000). Face and content validity is evidenced by the MSCEIT's accurate depiction of the four branch Model (Mayer et al., 2000) and appropriate convergent, discriminant, and incremental validity has been established (Brackett & Mayer, 2003).

Positive and negative empathyPositive and negative empathy were measured with the Positive and Negative Empathy Scales (PaNES) (Andreychik & Migliaccio, 2015). The positive empathy (e.g., “I often feel happy when those around me are smiling”) and negative empathy (e.g., “Seeing people cry upsets me”) scales each consist of seven items answered on a 0 (does not describe me well) to 4 (describes me very well) scale. Both scales have demonstrated high reliability (αs=.86–.92). Convergent and discriminant validity of the PaNES was established across two separate samples.

Compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction, burnoutThe ProQOL5 is a 30-item self-report measure containing three subscales: compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout (Figley & Stamm, 1996). Each subscale has 10 items, which are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1=never to 5=very often. Convergent and discriminant validity testing established that each scale evaluates different constructs, with reliabilities ranging from .84 to .90 (Stamm, 2010) and adequate construct validity and reliability (Stamm, 2010). A compassion satisfaction score of 22 or less indicates low levels, 23–41 denotes average levels, and 42 and above signifies high levels of compassion satisfaction. For compassion fatigue and burnout, a score of 22 or less denotes low levels, 23–41 signifies average levels, and a score of 42 and higher indicates high levels of compassion fatigue and burnout.

DemographicsDemographic data were gathered on age, gender, marital status, and ethnicity, as well as level of education, years in the field, patient setting, typical length of shift, direct patient care hours per week, manager support, and region of the United States that the participants work.

Statistical analysisData were analyzed using PASW Statistics 18. Demographic variables that were nominal in nature (gender, marital status, ethnicity, highest level of education, setting, and United States region) were analyzed using proportion (%) and absolute number (N) statistics. Demographic variables that yield interval data (age, years in the profession, number of direct patient care hours per week, length of typical work day, and supportiveness of manager) were analyzed using measures of central tendency (M), dispersion (SD, R), proportion (%), and absolute number (N). For the research questions, the statistical plan was to conduct a corrrelational coefficient Pearson Product Moment. The alpha level was set at p<.05.

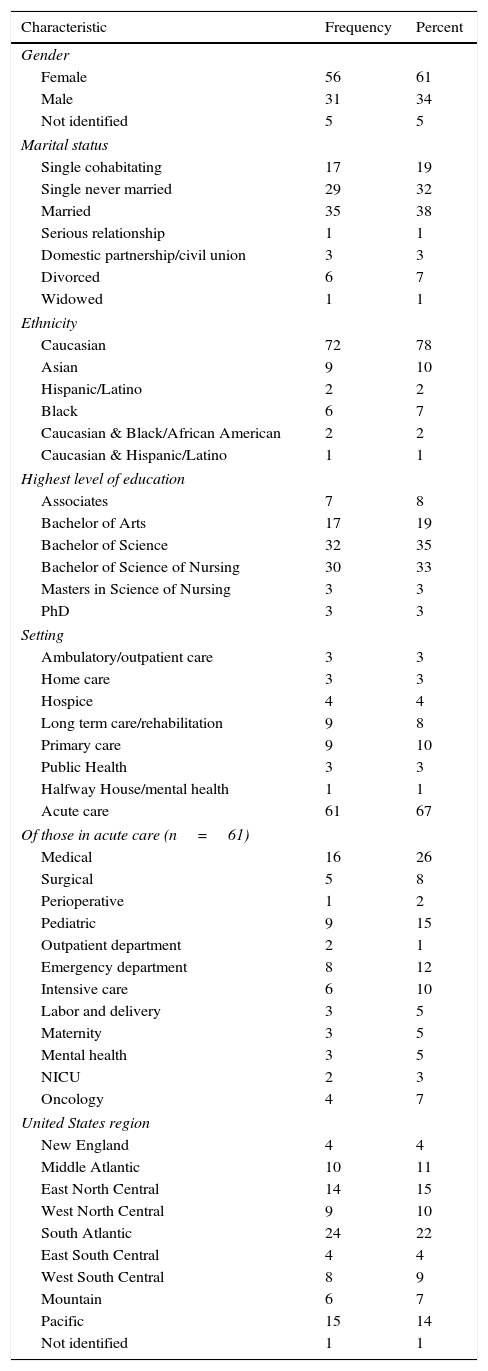

ResultsInitially, 100 nurses were recruited to participate but 8 either did not complete all measures or failed to follow directions regarding producing a subject code that allowed their data from the different surveys to be matched and were therefore removed from the dataset, resulting in a final sample of 92. This is still greater than the 82 participants needed for adequate power (described earlier). Eleven key characteristics were analyzed as demographic variables such as age, gender, and educational and professional experience (see Tables 1 and 2). The 92 nurses participating in the research study were mostly Caucasians between the ages of 20 and 60 and holding a bachelor's degree. Participants worked in a variety of settings in all regions of the United States.

Characteristics of the participants (N=92).

| Characteristic | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 56 | 61 |

| Male | 31 | 34 |

| Not identified | 5 | 5 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single cohabitating | 17 | 19 |

| Single never married | 29 | 32 |

| Married | 35 | 38 |

| Serious relationship | 1 | 1 |

| Domestic partnership/civil union | 3 | 3 |

| Divorced | 6 | 7 |

| Widowed | 1 | 1 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 72 | 78 |

| Asian | 9 | 10 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 2 | 2 |

| Black | 6 | 7 |

| Caucasian & Black/African American | 2 | 2 |

| Caucasian & Hispanic/Latino | 1 | 1 |

| Highest level of education | ||

| Associates | 7 | 8 |

| Bachelor of Arts | 17 | 19 |

| Bachelor of Science | 32 | 35 |

| Bachelor of Science of Nursing | 30 | 33 |

| Masters in Science of Nursing | 3 | 3 |

| PhD | 3 | 3 |

| Setting | ||

| Ambulatory/outpatient care | 3 | 3 |

| Home care | 3 | 3 |

| Hospice | 4 | 4 |

| Long term care/rehabilitation | 9 | 8 |

| Primary care | 9 | 10 |

| Public Health | 3 | 3 |

| Halfway House/mental health | 1 | 1 |

| Acute care | 61 | 67 |

| Of those in acute care (n=61) | ||

| Medical | 16 | 26 |

| Surgical | 5 | 8 |

| Perioperative | 1 | 2 |

| Pediatric | 9 | 15 |

| Outpatient department | 2 | 1 |

| Emergency department | 8 | 12 |

| Intensive care | 6 | 10 |

| Labor and delivery | 3 | 5 |

| Maternity | 3 | 5 |

| Mental health | 3 | 5 |

| NICU | 2 | 3 |

| Oncology | 4 | 7 |

| United States region | ||

| New England | 4 | 4 |

| Middle Atlantic | 10 | 11 |

| East North Central | 14 | 15 |

| West North Central | 9 | 10 |

| South Atlantic | 24 | 22 |

| East South Central | 4 | 4 |

| West South Central | 8 | 9 |

| Mountain | 6 | 7 |

| Pacific | 15 | 14 |

| Not identified | 1 | 1 |

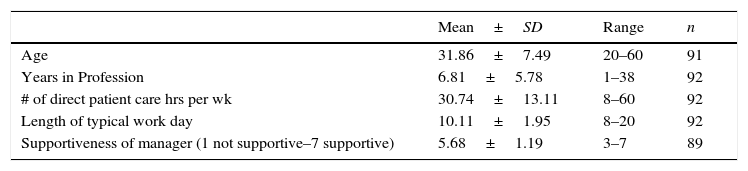

Professional experience of participants (N=92).

| Mean±SD | Range | n | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 31.86±7.49 | 20–60 | 91 |

| Years in Profession | 6.81±5.78 | 1–38 | 92 |

| # of direct patient care hrs per wk | 30.74±13.11 | 8–60 | 92 |

| Length of typical work day | 10.11±1.95 | 8–20 | 92 |

| Supportiveness of manager (1 not supportive–7 supportive) | 5.68±1.19 | 3–7 | 89 |

The MSCEIT measured emotional intelligence in this study. Higher MSCEIT scores indicate greater emotional intelligence ability. Scores can range from 0 to 100. Reliability for the MSCEIT total scale was confirmed with a Guttman split-half reliability of .81. As seen in Table 3, the mean total score was moderately high, with highest scores for Branch 1 (perceiving emotions), followed by Branch 3 (understanding emotion) and Branch 2 (using emotion), and lowest for Brach 4 (managing emotion).

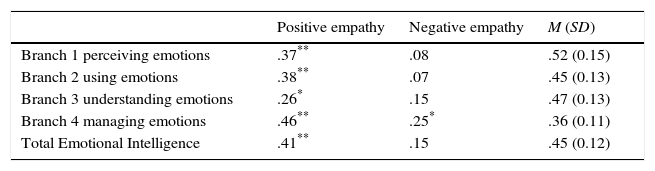

Correlations between positive and negative empathy and emotional intelligence branch scores and total (MSCEIT).

The PaNES scale measured positive and negative empathy in this study. PaNES scores can range from 0 to 4. Higher scores on each subscale indicate greater self-reported positive/negative empathy. Reliability was confirmed for this study with an overall Cronbach's alpha of .81 for negative empathy and .90 for positive empathy. As seen in Table 3, positive empathy scores were higher overall than negative empathy scores, replicating the pattern found in past research (Andreychik & Migliaccio, 2015).

What is the relationship between emotional intelligence (total and branch scores) and positive and negative empathy?Correlational analyses (see Table 31) show that the relationship between total emotional intelligence and positive empathy was statistically significant, r(85)=.41, p<.01. The relationship between total emotional intelligence and negative empathy was not statistically significant. The relationships among emotional intelligence branch scores and positive and negative empathy scores were evaluated. Branch one (perceiving emotions), branch two (using emotions), branch three (understanding emotions), and branch four (managing emotions) scores had significant correlations with positive empathy, respectively r(85)=.37, p<.01, r(85)=.38, p<.01, r(85)=.26, p=.01, r(85)=.46, p<.01. Branch four (managing emotions) score had a significant correlation with negative empathy, r(88)=0.25, p=.02. The other branch scores were not significantly correlated with negative empathy.

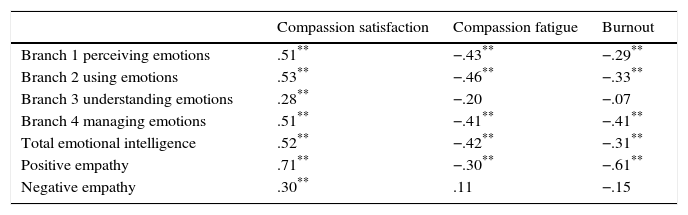

What is the relationship between emotional intelligence (total and branch scores) and compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout?Correlational analyses (see Table 4) showed a significant, positive relationship between total emotional intelligence and compassion satisfaction, r(90)=.52, p<.01. Branch one (perceiving emotions), branch two (using emotions), branch three (understanding emotions), and branch four (managing emotions) scores had significant correlations with compassion satisfaction, respectively r(90)=.51, p<.01, r(90)=.53, p<.01, r(90)=.28, p<.01, r(90)=.51, p<.01.

Correlations between compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, burnout and emotional intelligence branch scores, emotional intelligence total score, positive empathy, and negative empathy.

| Compassion satisfaction | Compassion fatigue | Burnout | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Branch 1 perceiving emotions | .51** | −.43** | −.29** |

| Branch 2 using emotions | .53** | −.46** | −.33** |

| Branch 3 understanding emotions | .28** | −.20 | −.07 |

| Branch 4 managing emotions | .51** | −.41** | −.41** |

| Total emotional intelligence | .52** | −.42** | −.31** |

| Positive empathy | .71** | −.30** | −.61** |

| Negative empathy | .30** | .11 | −.15 |

Correlational analyses showed a significant negative relationship between total emotional intelligence and compassion fatigue, r(90)=−.42, p<.01. Branch one (perceiving emotions), branch two (using emotions), and branch four (managing emotions) scores had significant negative correlations with compassion fatigue, respectively r(90)=−.43, p<.01, r(90)=−.46, p<.01, r(90)=−.41, p<.01. Branch 3 (understanding emotion) was not significantly correlated with compassion fatigue.

Correlational analyses showed a significant negative relationship between total emotional intelligence and burnout, r(90)=−.31, p<.01. Branch one (perceiving emotions), branch two (using emotions), and branch four (managing emotions) scores had significant negative correlations with burnout, respectively r(90)=−.029, p=.01, r(90)=−.33, p<.01, r(90)=−.41, p<.01. Branch 3 (understanding emotion) was not significantly correlated with burnout.

What is the relationship between positive and negative empathy and compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout?Correlational analyses (see Table 4) showed a significant, positive relationship between positive empathy scores and compassion satisfaction, r(85)=.71, p<.01. Positive empathy had significant negative relationships with compassion fatigue and burnout, respectively r(85)=−.30, p<.01 and r(85)=−.61, p<.01. Negative empathy scores had a statistically significant positive correlation with compassion satisfaction scores, r(88)=.30, p<.01. Negative empathy was not significantly correlated with compassion fatigue or burnout scores.

DiscussionEmotional intelligence and empathyThe significant relationship between emotional intelligence (total and branch scores) and positive empathy supports statements in the literature that empathy is a key component of emotional intelligence as empathy involves the ability to understand another's emotion (Ioannidou & Konstantikaki, 2008; King et al., 2012; Martos et al., 2013; Salovey & Mayer, 1990; Shanta & Gargiulo, 2014). The findings support the developing view that empathy is more than just connecting with others’ emotions broadly speaking, and that different styles or types of empathy exist. Positive empathy (relating to patient's positive emotions such as happiness and optimism) was found to be related to emotional intelligence in the study's sample of nursing professionals, but negative empathy (relating to patient's negative emotions such as sadness and pain) for the most part was not related to emotional intelligence. In different contexts, different styles of empathy can be beneficial, and it appears that nurses higher in emotional intelligence tend to engage in positive empathy as part of their healthcare practice. For example, the emotionally intelligent nurse might perceive joy in a patient who has just given birth. The nurse may empathize and feel that joy as well. The nurse might use that emotional information to facilitate thinking and manage the situation to help the mother bond with the baby.

The flip side of this is nurses who tend to empathize too much with patients’ negative emotions (their pain, their fears, their distress) may be inadvertently engaging in unhealthy styles of empathy in this context. In general, emotional intelligence and negative empathy were not related (except for branch 3, managing emotions). For example, the emotionally intelligent nurse might recognize from a patient's expression that he is anxious. Although the nurse might understand this emotion and recognize that it is related to an upcoming surgery in which the patient worries about the lack of control and fears the unknown, this does not mean that the nurse is empathizing with that negative emotion or feeling the same emotion. Most likely the nurse recognizes that the surgery will help the patient and chooses to focus on the hope the surgery will provide. The emotionally intelligent nurse can help the patient manage the anxiety with relaxation techniques, and when the patient's anxiety decreases the nurse can offer education to decrease the fear of the unknown.

Interestingly, the one correlation between emotional intelligence and negative empathy was with the branch of emotional intelligence that deals with managing emotions. In healthcare, ignoring negative emotions can be perceived as being cold or uninvolved, and thus skills at managing negative emotions may be especially valuable and something that people with experience with these sorts of situations might either develop out of necessity or might be something that draws people to the profession in the first place (e.g., “I can help others because I am able to keep myself calm in extreme situations”). For instance, an emotionally intelligent nurse may perceive that a physician is angry when he/she comes to the unit to visit a patient only to find the patient is off the floor at testing. The nurse might understand the physician's frustration as he/she knows the physician has other pressing demands. The nurse may not feel the same feelings as the physician. However, an emotionally intelligent nurse can manage the physician's anger by acknowledging the inconvenience and problem solving the situation.

Emotional intelligence and compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnoutEmotional intelligence (total and branch scores) was positively correlated with compassion satisfaction. Emotional intelligence (total and branch scores except branch 3: understanding emotion) was negatively correlated with both compassion fatigue and burnout. These findings support previous findings in the literature that emotional intelligence influences burnout and caring of nurses (Kaur et al., 2013) and that emotional intelligence effects nurses’ well-being and perceived job stress (Karimi et al., 2013). These findings suggest that emotional intelligence might aid in an individual's compassion satisfaction, perhaps because individuals high in emotional intelligence are both more accurate in their perceptions of others’ emotions and better able to manage their own emotions. If one can accurately perceive another's emotions, this is likely to increase the extent to which one takes appropriate steps to respond to and comfort the other (e.g., neither minimizing nor over-reacting to a patient's actual experienced pain). Such appropriate responses are likely to be met with more positive responses from the other (e.g., gratefulness, a sense of being understood), which might increase the satisfaction one takes from the experience of feeling compassion for the other. Furthermore, emotional intelligence might serve as a protective factor against compassion fatigue and burnout as one is able not only to perceive and use emotions but also to manage those emotions. For example, a patient might be angry over a diagnosis and not willing to accept care from the treatment team. A nurse who has higher emotional intelligence will be able to recognize the patient's anger and meet the patient where he/she is emotionally and not feel overcome (fatigued and burnt-out) by the negative emotions. The emotionally intelligent nurse could help manage the patient's anger and assist the patient in coming to terms with the diagnosis thus bringing the nurse some sense of satisfaction.

Empathy and compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and burnoutPositive empathy was associated with greater compassion satisfaction, less compassion fatigue, and less burnout. Negative empathy was associated with greater compassion satisfaction. This is believed to be the first study looking at these relationships. These findings suggest that empathy whether positive or negative aids in the development of an individual's compassion satisfaction. However, positive empathy alone serves as a mitigating factor against burnout and compassion fatigue. These findings suggest that the more nurses connect with their patients’ positive emotions, the more positive and the less emotionally-draining is the emotional support aspect of their work.

Implications for clinical practiceThe findings from this study are valuable as they not only raise awareness but ultimately assist in identifying strategies, supports, and solutions to help decrease compassion fatigue and burnout while increasing compassion satisfaction in clinicians. Such strategies could potentially help maintain positive therapeutic relationships and reduce the potential negative effects of employment. Compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and burnout are known precursors of job retention (Hayes, Bonner, & Pryor, 2010; Ritter, 2011). As clinicians experience compassion fatigue and the related consequences, institutions are at risk for not only clinician attrition but also decreased patient satisfaction and quality of care, which in turn can lead to reduced reimbursement and diminished patient volume (Hammerly, Harmom, & Schwaitzberg, 2014; Kelly et al., 2015; Shanta & Gargiulo, 2014; Tyler, 2015). Theoretically, finding methods to enhance an individual's emotional intelligence and empathy (positive and negative) may facilitate the development of compassion satisfaction. In addition, implementing strategies to improve an individual's emotional intelligence and positive empathy may help protect against compassion fatigue and burnout. Such strategies could be conducted in settings where there is a higher level of clinician stress, burnout and attrition as well as on those units/specialties that have decreased patient satisfaction scores. Supports could be initiated for clinicians during orientation and continued through mentorship and support groups (Hayes et al., 2010). For example, one of the authors is currently designing and validating an easy-to-implement positive empathy intervention. If successful at increasing levels of positive empathy, such an intervention could be easily adapted to healthcare settings.

While the present findings are overall revealing, certain issues should be considered. Generalizability of findings may be limited given the small sample size and relatively homogenous group, and validity is impacted by the use of self-report measures. The cross-sectional design is a limitation as the results may be related to a number of other considerations such as short staffing or high patient acuity (Sabo, 2011). In addition, the compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout measurements were taken at one point in time, though indeed participant's perceptions may change over time depending on their work conditions (Stamm, 2010).

Future researchFurther exploration of how emotional intelligence and positive empathy function as protective factors for compassion fatigue and burnout is warranted. Future research could focus on the development of programs that would help foster emotional intelligence and positive empathy abilities to help clinicians handle the stress of caring for patients in today's complex healthcare environment (Hunsaker et al., 2015).

Additionally, future research could examine the relationship of compassion fatigue and burnout on such factors as quality of patient care, attrition of clinicians, and financial repercussions (Kelly et al., 2015). Given healthcare reform and the institution of pay-for-performance, clinicians are feeling additional pressures to provide quality patient outcomes (Kelly et al., 2015). Clinicians strive to weigh the demands of positive patient outcomes and patient satisfaction with the mounting role responsibility and demand for increased efficiency (Hooper, Craig, Janvrin, Wetsel, & Reimels, 2010).

ConclusionAs the demands of the healthcare environment increase and roles expand, clinicians can expect this will influence their emotional and professional well-being. This study confirms the potential benefit of emotional intelligence and empathy in preventing compassion fatigue and burnout while promoting compassion satisfaction. The results support healthcare organizations implementing training session to enhance clinicians’ emotional intelligence abilities and positive empathy. Such strategies will not only help facilitate compassion satisfaction and help protect against compassion fatigue but may also help promote clinician retention and improve the quality of patient care (Kelly et al., 2015).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding to support this research was obtained from the Sigma Theta Tau International Mu Chi Chapter Research Grant as well as from the Marion Peckham Egan School of Nursing & Health Studies and the College of Arts & Sciences at Fairfield University, Fairfield, CT, USA.