The Mini-Cog is a very brief, widely used cognitive test that includes a memory task and a simplified assessment of the Clock Drawing Test (CDT). There is not a formal evaluation of the Mini-Cog test in Spanish. This study aims to analyse the diagnostic usefulness of the Mini-Cog and CDT for detecting cognitive impairment (CI).

MethodsWe performed a cross-sectional study, systematically including all patients who consulted at our neurology clinic over a 6-month period. We assessed diagnostic usefulness for detecting CI (defined according to the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association criteria for mild cognitive impairment and dementia) according to the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative likelihood ratios were calculated for each cut-off point.

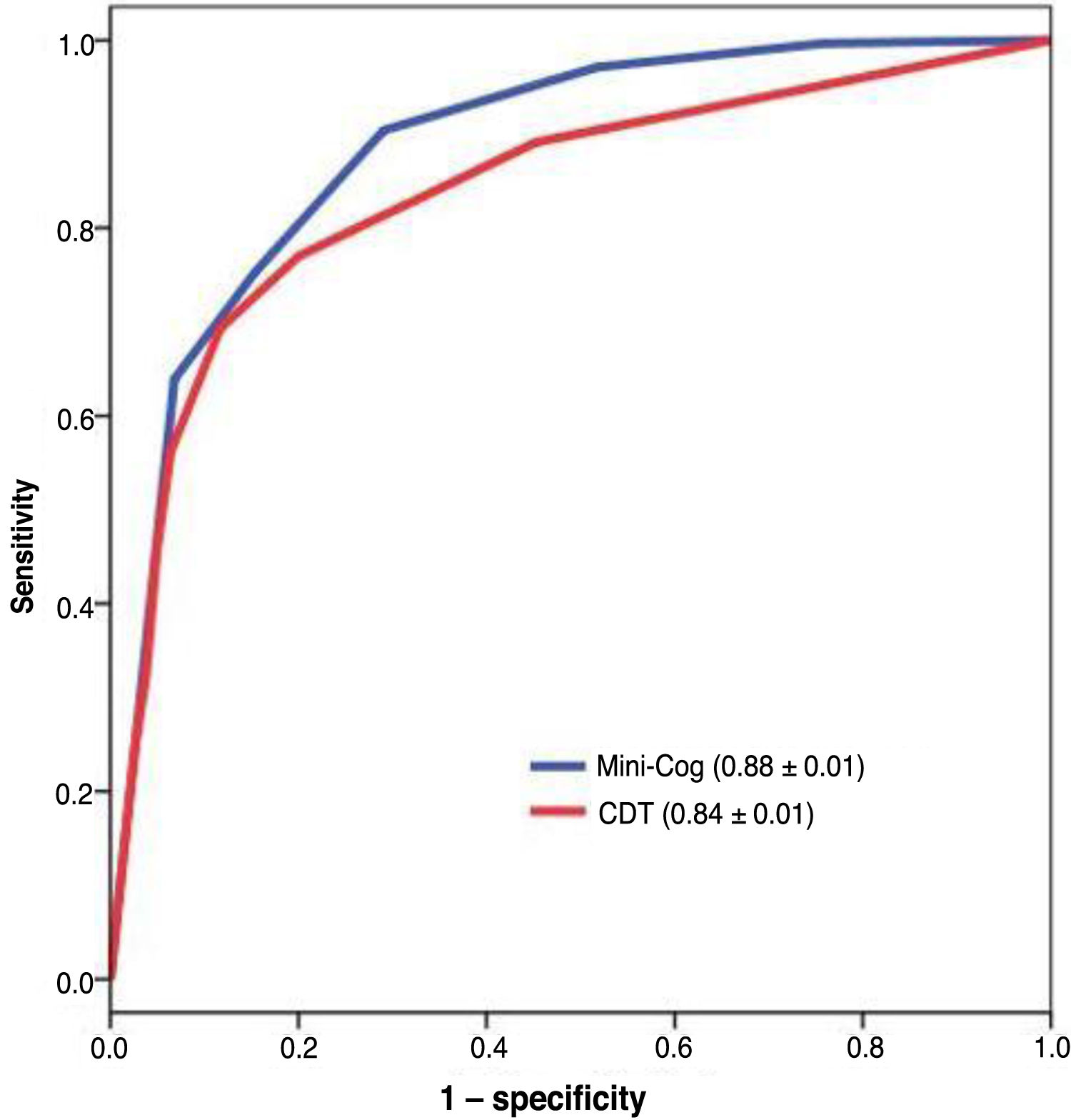

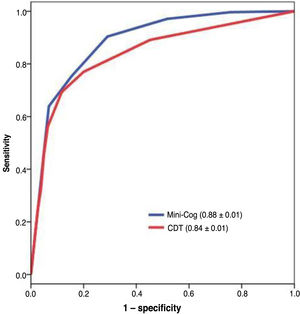

ResultsThe study included 581 individuals (315 with CI); 55.1% were women and 27.7% had not completed primary studies. The Mini-Cog showed greater diagnostic usefulness than the CDT (AUC ± sensitivity: 0.88 ± 0.01 vs 0.84 ± 0.01; P < .01). Both instruments were less useful for screening in individuals with a low education level (0.74 ± 0.05 vs 0.75 ± 0.05, respectively). A cut-off point of 2/3 in the Mini-Cog achieved a sensitivity of 0.90 (95% CI, 0.87-0.93) and a specificity of 0.71 (95% CI, 0.65-0.76); a cut-off point of 5/6 in the CDT achieved a sensitivity of 0.77 (95% CI, 0.72-0.81) and a specificity of 0.80 (95% CI, 0.75-0.85).

ConclusionIn our neurology clinic, the Mini-Cog showed acceptable diagnostic usefulness for detecting CI, greater than that of the CDT; neither test is an appropriate instrument for individuals with a low level of education.

El Mini-Cog es un test cognitivo muy breve de uso extendido que incluye una tarea de memoria y una evaluación simplificada del Test del Reloj (TdR). No existe una evaluación formal del Mini-Cog en español; nuestro objetivo es analizar la utilidad diagnóstica (UD) del Mini-Cog y del TdR para deterioro cognitivo (DC).

MétodosEstudio transversal en el que se han incluido de forma sistemática todos los sujetos atendidos durante un semestre en una consulta de Neurología. La UD se ha evaluado para DC (incluye sujetos con criterios NIA-AA de mild cognitive impairment o demencia) por medio del área bajo la curva ROC (aROC). Se han calculado los parámetros de sensibilidad (S), especificidad (E) y cocientes de probabilidad positivo y negativo (CP+, CP-) para los distintos puntos de corte.

ResultadosSe han incluido 581 sujetos (315 DC), 55.1% mujeres y 27.7% con bajo nivel educativo (< estudios primarios). La UD del Mini-Cog es superior a la del TdR (0.88 ± 0.01 (aROC ± ee) vs 0.84 ± 0.01, P < .01); para ambos instrumentos, la UD disminuye notablemente en sujetos con bajo nivel educativo (0.74 ± 0.05 y 0.75 ± 0.05 respectivamente). El punto de corte 2/3 del Mini-Cog tiene una S 0.90 (0.87−0.93) y una E 0.71 (0.65−0.76) y el 5/6 del TdR una S 0.77 (0.72−0.81) y E 0.80 (0.75−0.85).

ConclusionesEn consulta de Neurología, el Mini-Cog tiene una UD para DC aceptable, superior a la del TdR; ninguno de ellos es un instrumento adecuado para ser utilizado en sujetos con bajo nivel educativo.

Subjective cognitive complaints and memory loss constitute a frequent reason for consultation with primary care and referral to the neurology department.1 Initial assessment and follow-up of these patients requires the use of valid cognitive assessment tools that are brief enough to be administered during consultations.2

The Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE),3 currently the most frequently used cognitive assessment tool, is rapidly losing supporters due to numerous limitations, including its cost,4 and was even excluded from the third version of the Alzheimer Disease Centers’ Neuropsychological Test Battery.5 The Montreal Cognitive Assessment,6 in contrast, is increasingly popular. It includes multiple domains, but has an even longer administration time than the MMSE, which limits its use in general consultations and particularly in primary care.

The clock drawing test (CDT), one of the oldest and most widely used brief cognitive tests,7 is considered by some authors to be the ideal cognitive screening test due to its simplicity and brevity.8 However, it does present some limitations: it does not explicitly evaluate episodic memory; it requires a minimum level of graphomotor skills (which may be problematic for illiterate individuals or those with a low level of education)9; it does not have a simple, standardised grading system10; and its diagnostic accuracy is limited.11

The Mini-Cog,12 a simple, quick-to-administer instrument, aims to address some of the limitations of the CDT: it includes a 3-item free recall task and a simplified clock-drawing task.8 It has been validated in multiple settings (community,13 primary care,14 specialised clinics15) and in numerous languages (available at https://mini-cog.com/mini-cog-in-other-languages/). Furthermore, there are 15 versions of the Mini-Cog, which differ in the set of items the patient has to recall (5 options) and the time to which the clock has to be set (3 options).16 The Mini-Cog is currently one of the most widely recommended dementia screening tools for primary care and general consultations.17–22

The Mini-Cog has been used in some studies conducted in Spanish-speaking countries,23,24 although no formal evaluation of the Spanish-language version has been conducted to date. In Spain, one study did evaluate the test’s diagnostic usefulness, calculating results retrospectively by adding together scores for CDT drawings and the MMSE recall task, which had previously been administered independently; however, the Mini-Cog was not actually administered.25

The purpose of this study was to formally evaluate the discriminant validity and diagnostic usefulness of the CDT and the Mini-Cog for identifying individuals with cognitive impairment in a large sample of patients attended at the neurology clinic.

MethodsDesignWe conducted a cross-sectional study including all patients attended between March and September 2018 at a neurology clinic specialising in cognitive and behavioural neurology.

For patients attended on more than one occasion during the study period, we only included the data corresponding to the last evaluation, as these were considered to be the most reliable from a diagnostic viewpoint.

Cognitive assessmentAll patients underwent a brief cognitive assessment including the Mini-Cog, the CDT, and the Fototest,26 regardless of the reason for consultation.

All patients attended due to subjective or informant-reported memory complaints and/or behavioural alterations, or those scoring below the 10th percentile on the Fototest,27 underwent a thorough cognitive assessment including orientation (temporal, spatial, and personal), attention (forward and backward digit span), memory (learning, free recall, and recognition of the CERAD word list28), language (short version of the Boston Naming Test,29 semantic verbal fluency,30 comprehension of commands), motor apraxia (EULA test31), executive function (WAIS similarities, coin test from the Eurotest,32 semantic verbal fluency), and visuospatial function (copy and drawing), in addition to a formal functional evaluation. The researcher performing the assessment (SLA) was blinded to Mini-Cog, CDT, and Fototest results.

Mini-CogVersion usedWe used the Mini-Cog16 version including the words “capitán,” “jardín,” and “retrato” (captain, garden, picture), the word combination showing the most homogeneous frequency of use in Spanish (58.67, 62.45, and 38.42 occurrences per million words, respectively),33 and the clock time “10 past 11,” the most frequently used clock time in our setting.

AdministrationPatients were given the following instructions: “Please listen carefully. I am going to say 3 words that I want you to repeat back to me; try to remember them as I will ask you to repeat them again.” If the person was unable to repeat all 3 words, the instructions were repeated up to 3 times. Patients were then given a blank sheet and a pencil, and the following instructions were given: “Next, I want you to draw a large, round clock for me. First, put all of the numbers in their places. Then, set the hands to 10 past 11.” After the clock-drawing task was completed, the patient was asked to recall the 3 words from the first task.

ScoringIn the recall task, one point was scored for each word that was correctly remembered. The clock drawing task was scored the maximum score (2 points) if the drawing met all of the following conditions:

- 1

The clock has all the numbers, with no repetitions and no additional numbers.

- 2

The numbers are placed in the correct order.

- 3

The numbers are placed in the correct positions on the face of the clock.

- 4

The hands are unequivocally set to the time asked.

Any other situation, including the patient refusing to draw the clock or being unable to do so due to physical limitations (paresis, tremor, ataxia, etc), was scored 0 points.

RegistryWe recorded patients’ scores, the time taken to complete the test, the total number of attempts to repeat the 3 words, and the number of times the rater had to repeat the instructions for the clock drawing task.

Clock drawing testWe used the scoring system of the Spanish-language version of the Seven-Minute Screen34 to score the clock drawing task in the Mini-Cog; this system scores one point for each of the following criteria:

- 1

The clock has all numbers from 1 to 12 (using either Arabic or Roman numerals).

- 2

The numbers are placed in the correct ascending order (even if not all 12 numbers have been placed).

- 3

The numbers are in the correct positions.

- 4

The clock has 2 hands (circles or other marks are not valid).

- 5

The hour hand (or any other mark) is set to 11.

- 6

The minute hand (or any other mark) is set to 10.

- 7

The hour hand is shorter than the minute hand (or the patient indicates so orally).

Regardless of the reason for consultation and the final aetiological diagnosis, all patients were categorised by cognitive status, as follows:

- -

Normal cognitive function (NCF): no subjective cognitive complaints and age-, sex-, and education-adjusted Fototest scores above the 10th percentile.27

- -

Subjective cognitive complaints (SCC): presence of subjective cognitive complaints, with normal results in the formal cognitive assessment.

- -

Cognitive impairment without associated functional limitations (CIw/o): presence of alterations in at least one cognitive domain according to the formal cognitive assessment, with no significant impact on functional status; these individuals meet the National Institute of Aging–Alzheimer’s Association criteria for mild cognitive impairment.35

- -

Cognitive impairment with associated functional limitations (CIw): presence of alterations in at least one cognitive domain according to the formal cognitive assessment, with significant impact on functional status; these individuals meet the National Institute of Aging–Alzheimer’s Association criteria for dementia.36 In line with the recommendations of other authors,37 we avoid using the term “dementia” due to its negative connotations and the associated stigma.

We conducted a descriptive study of sociodemographic variables and results, stratified by diagnosis; comparisons were performed using ANOVA and the chi-square test, depending on whether variables were continuous or categorical.

The diagnostic usefulness of the tests was evaluated with the area under the ROC curve in patients with (CIw/o + CIw) vs without cognitive impairment (NCF + SCC). We calculated the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative likelihood ratios for different cut-off points. We used the Hanley and McNeil method for comparing ROC curves from the same sample38 and the DeLong method for comparing ROC curves from independent samples.39 All parameters were calculated with 95% confidence intervals and two-way comparisons with an alpha error of 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed with MedCalc, version 18.9.1.40

Formal considerationsThe study design and manuscript preparation follow the STARD recommendations for studies evaluating diagnostic tests.41

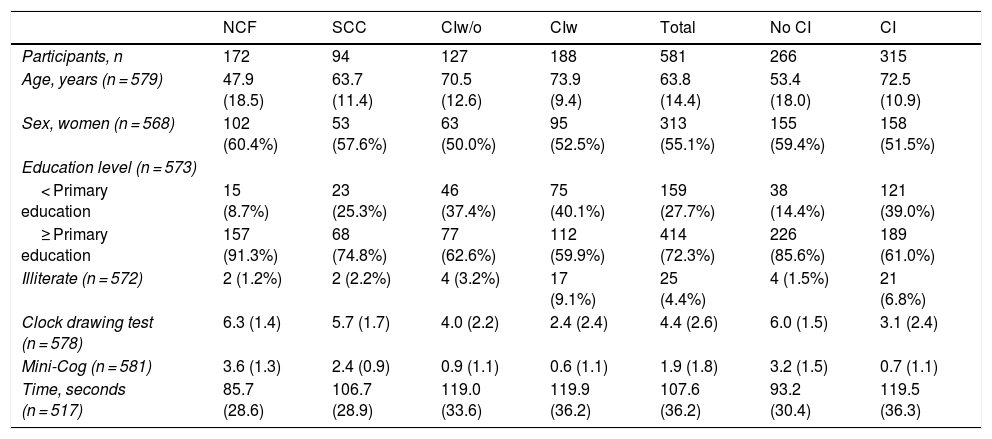

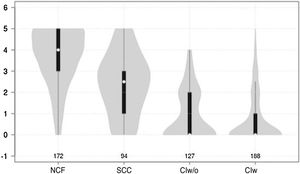

ResultsWe included a total of 581 individuals, 266 of whom (45.8%) did not have cognitive impairment; 94 of these (16.2%) had SCC. The remaining 315 (54.2%) had cognitive impairment: 127 (21.9%) had no functional limitations and 188 (32.1%) presented functional limitations. Table 1 summarises the sociodemographic characteristics and cognitive assessment results of our sample. Participants had a mean (SD) age of 63.8 (14.4) years (range, 15–92) and 55.1% were women. No differences in sex distribution were observed between groups (χ2 = 3.94; not significant) but we did observe differences in age, which increased with poorer cognitive status (F = 121.9; P < .001), and education level, which was lower in individuals with poorer cognitive status (χ2 = 53.68; P < .001). We also observed an inverse correlation between the percentage of illiterate individuals and cognitive status (χ2 = 61.17; P < .001).

Sociodemographic characteristics and cognitive test results.

| NCF | SCC | CIw/o | CIw | Total | No CI | CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants, n | 172 | 94 | 127 | 188 | 581 | 266 | 315 |

| Age, years (n = 579) | 47.9 (18.5) | 63.7 (11.4) | 70.5 (12.6) | 73.9 (9.4) | 63.8 (14.4) | 53.4 (18.0) | 72.5 (10.9) |

| Sex, women (n = 568) | 102 (60.4%) | 53 (57.6%) | 63 (50.0%) | 95 (52.5%) | 313 (55.1%) | 155 (59.4%) | 158 (51.5%) |

| Education level (n = 573) | |||||||

| < Primary education | 15 (8.7%) | 23 (25.3%) | 46 (37.4%) | 75 (40.1%) | 159 (27.7%) | 38 (14.4%) | 121 (39.0%) |

| ≥ Primary education | 157 (91.3%) | 68 (74.8%) | 77 (62.6%) | 112 (59.9%) | 414 (72.3%) | 226 (85.6%) | 189 (61.0%) |

| Illiterate (n = 572) | 2 (1.2%) | 2 (2.2%) | 4 (3.2%) | 17 (9.1%) | 25 (4.4%) | 4 (1.5%) | 21 (6.8%) |

| Clock drawing test (n = 578) | 6.3 (1.4) | 5.7 (1.7) | 4.0 (2.2) | 2.4 (2.4) | 4.4 (2.6) | 6.0 (1.5) | 3.1 (2.4) |

| Mini-Cog (n = 581) | 3.6 (1.3) | 2.4 (0.9) | 0.9 (1.1) | 0.6 (1.1) | 1.9 (1.8) | 3.2 (1.5) | 0.7 (1.1) |

| Time, seconds (n = 517) | 85.7 (28.6) | 106.7 (28.9) | 119.0 (33.6) | 119.9 (36.2) | 107.6 (36.2) | 93.2 (30.4) | 119.5 (36.3) |

CI: cognitive impairment; CIw: cognitive impairment with associated functional limitations; CIw/o: cognitive impairment without associated functional limitations; NCF: normal cognitive function; SCC: subjective cognitive complaints.

Data are expressed either as absolute frequency (%) or mean (standard deviation).

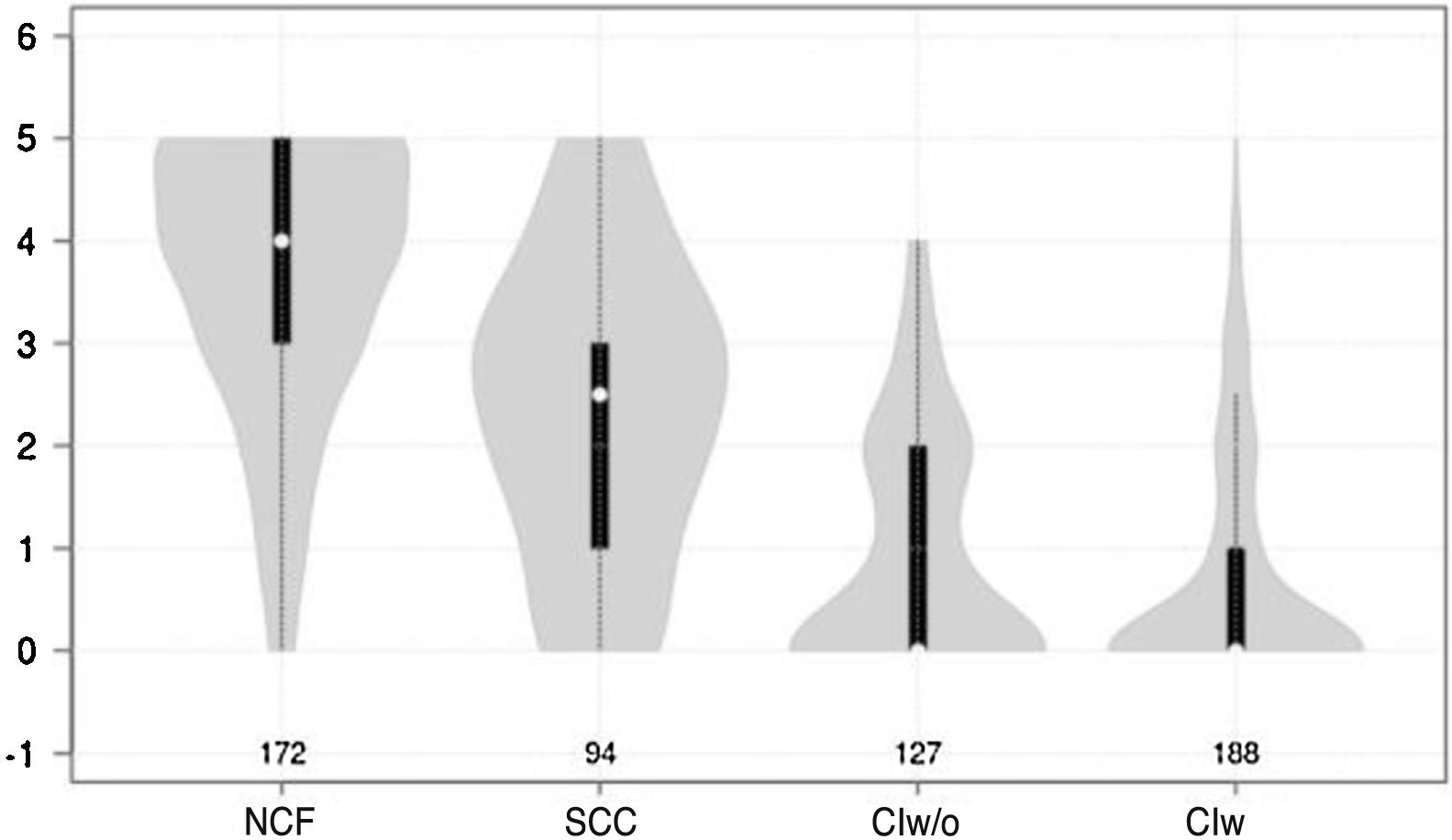

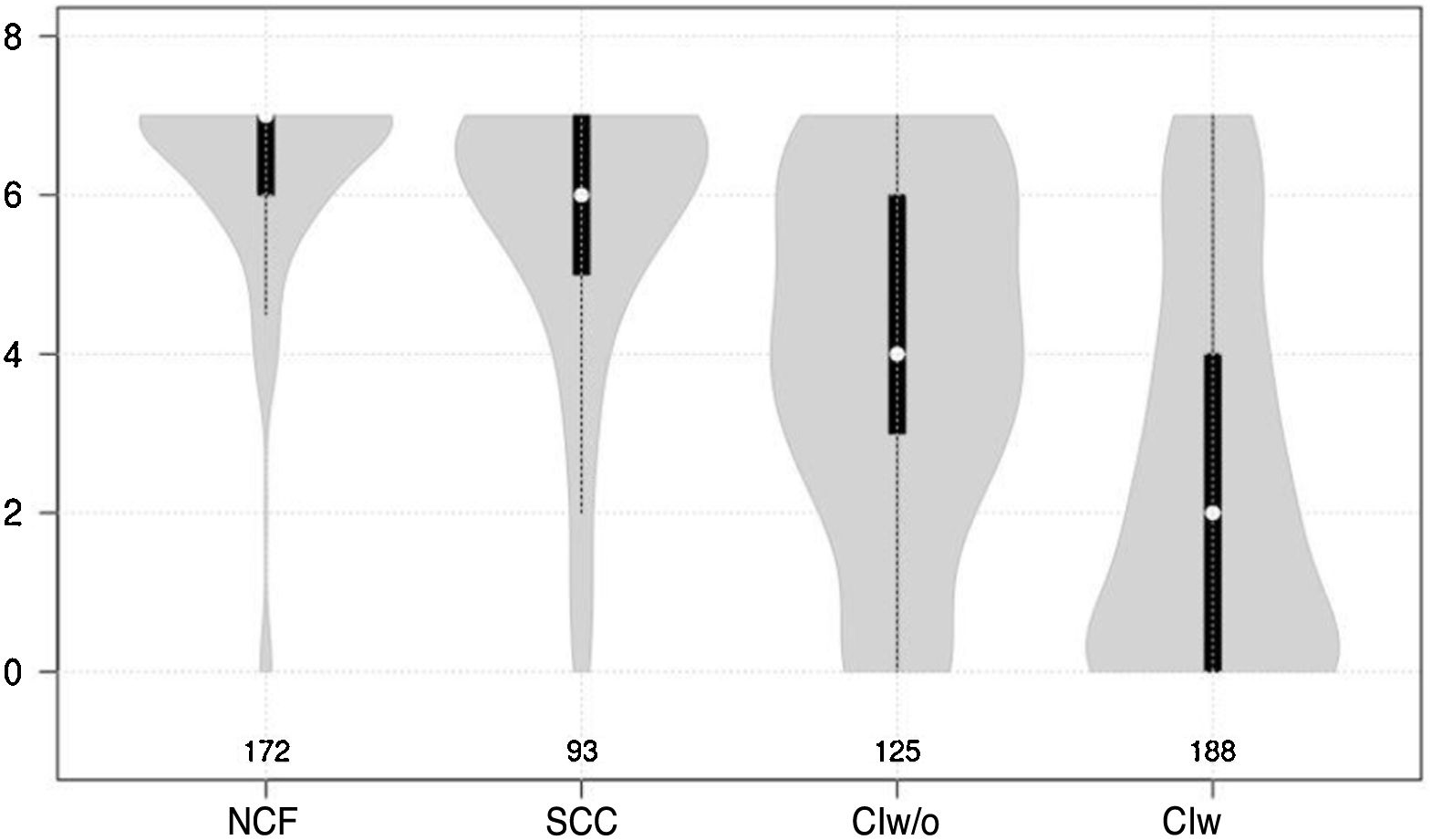

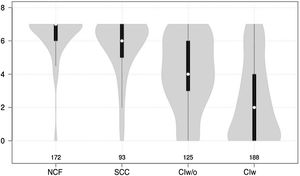

Cognitive test results showed a significant negative correlation with cognitive status (F = 210.7 for the Mini-Cog and F = 126.9 for the CDT; P < .0001 for both) (Figs. 1 and 2).

Violin plot showing Mini-Cog scores, stratified by cognitive status. The white dots represent median scores, the ends of the black bars represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the length of the line is 1.5 times the interquartile range; the violin shape represents the density distribution of the data, extending to the extreme high and low values. CIw: cognitive impairment with associated functional limitations; CIw/o: cognitive impairment without associated functional limitations; NCF: normal cognitive function; SCC: subjective cognitive complaints.

Violin plot showing clock drawing test scores, stratified by cognitive status. The white dots represent median scores, the ends of the black bars represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the length of the line is 1.5 times the interquartile range; the violin shape represents the density distribution of the data, extending to the extreme high and low values. CIw: cognitive impairment with associated functional limitations; CIw/o: cognitive impairment without associated functional limitations; NCF: normal cognitive function; SCC: subjective cognitive complaints.

Individuals with cognitive impairment completed the Mini-Cog in a mean of 119.5 (36.3) seconds (range, 55-266), nearly half a minute longer than it took individuals without cognitive impairment to complete the test (93.2 [30.4] seconds [range, 49-251]); the difference is highly significant (F = 34.2; P < .0001).

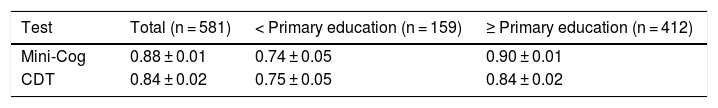

The diagnostic usefulness (area under the ROC curve ± standard error) of the Mini-Cog was significantly higher than that of the CDT (0.88 ± 0.01 vs 0.84 ± 0.01; P < .01) (Fig. 3). The diagnostic usefulness of the Mini-Cog and the CDT was highly influenced by level of education; performance was clearly poorer among individuals without primary studies (0.74 ± 0.05 and 0.75 ± 0.05, respectively) than among individuals with at least primary studies (0.90 ± 0.01 and 0.84 ± 0.02, respectively) (Table 2).

Diagnostic usefulness of the Mini-Cog and the clock drawing test.

| Test | Total (n = 581) | < Primary education (n = 159) | ≥ Primary education (n = 412) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mini-Cog | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.74 ± 0.05 | 0.90 ± 0.01 |

| CDT | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 0.75 ± 0.05 | 0.84 ± 0.02 |

CDT: clock drawing test.

Data represent the area under the ROC curve ± standard error.

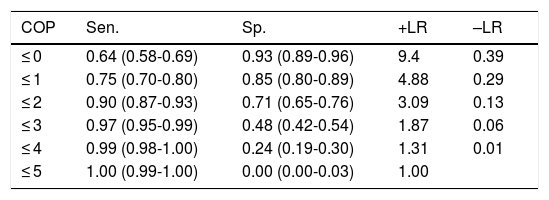

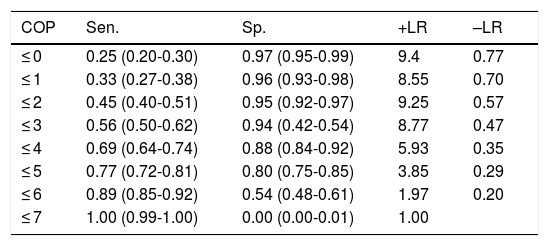

With the optimal cut-off point (2/3), the Mini-Cog has greater sensitivity (0.90) than specificity (0.71), correctly classifying 81.4% of the sample (Table 3); the CDT (cut-off point of 5/6, the score with the best diagnostic performance), in contrast, has greater specificity (0.80) than sensitivity (0.77), correctly classifying only 78.5% of individuals (Table 4).

Discriminant validity of the Mini-Cog in detecting cognitive impairment.

| COP | Sen. | Sp. | +LR | –LR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 0 | 0.64 (0.58-0.69) | 0.93 (0.89-0.96) | 9.4 | 0.39 |

| ≤ 1 | 0.75 (0.70-0.80) | 0.85 (0.80-0.89) | 4.88 | 0.29 |

| ≤ 2 | 0.90 (0.87-0.93) | 0.71 (0.65-0.76) | 3.09 | 0.13 |

| ≤ 3 | 0.97 (0.95-0.99) | 0.48 (0.42-0.54) | 1.87 | 0.06 |

| ≤ 4 | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.24 (0.19-0.30) | 1.31 | 0.01 |

| ≤ 5 | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) | 0.00 (0.00-0.03) | 1.00 |

+LR: positive likelihood ratio; –LR: negative likelihood ratio; COP: cut-off point; Sen.: sensitivity; Sp.: specificity.

Numbers shown in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals.

Discriminant validity of the clock drawing test in detecting cognitive impairment.

| COP | Sen. | Sp. | +LR | –LR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 0 | 0.25 (0.20-0.30) | 0.97 (0.95-0.99) | 9.4 | 0.77 |

| ≤ 1 | 0.33 (0.27-0.38) | 0.96 (0.93-0.98) | 8.55 | 0.70 |

| ≤ 2 | 0.45 (0.40-0.51) | 0.95 (0.92-0.97) | 9.25 | 0.57 |

| ≤ 3 | 0.56 (0.50-0.62) | 0.94 (0.42-0.54) | 8.77 | 0.47 |

| ≤ 4 | 0.69 (0.64-0.74) | 0.88 (0.84-0.92) | 5.93 | 0.35 |

| ≤ 5 | 0.77 (0.72-0.81) | 0.80 (0.75-0.85) | 3.85 | 0.29 |

| ≤ 6 | 0.89 (0.85-0.92) | 0.54 (0.48-0.61) | 1.97 | 0.20 |

| ≤ 7 | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) | 0.00 (0.00-0.01) | 1.00 |

+LR: positive likelihood ratio; –LR: negative likelihood ratio; COP: cut-off point; Sen.: sensitivity; Sp.: specificity.

Numbers shown in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals.

Our study included a large, heterogeneous sample of individuals attended at a neurology clinic, with a high prevalence of cognitive problems. In our sample, the Mini-Cog showed clearly greater diagnostic usefulness than the CDT; for both tests, the diagnostic usefulness is highly influenced by the patient education level.

The CDT presents limited diagnostic usefulness for cognitive impairment (area under the ROC curve: 0.84 ± 0.02); this is consistent with the results reported in previous studies, regardless of the correction method used, the setting, or the geographical location of the sample. Lee et al.42 and Duro et al.43 evaluated the diagnostic usefulness of the CDT for MCI using different correction methods; Ehreke et al.44 conducted a systematic review and concluded that the CDT is not suitable for cognitive impairment screening. A previous study conducted by our research group, including patients from primary care consultations and using the same grading system, shows identical results (0.84 ± 0.02); however, the study conducted by Cacho et al.,45 including patients attended at a neurology department and using a 10-point grading system,46 reports an even lower diagnostic usefulness for cognitive impairment (0.78).

The limited usefulness of the CDT may be due to the fact that the test does not specifically evaluate memory, the cognitive domain most frequently affected in patients with cognitive impairment; this would explain the superiority of the Mini-Cog, whose main difference with respect to the CDT is the inclusion of a free recall task.

The diagnostic usefulness of the Mini-Cog in our setting is acceptable (area under the ROC curve: 0.88 ± 0.02), similarly to the results of a study including a multiethnic sample with high prevalence of cognitive impairment (62.3%),47 and was clearly superior to the values obtained in 2 studies conducted in the primary care setting (with areas under the ROC curve of 0.66 and 0.77, respectively).20,25 The main difference between this study and our previous study25 is that in the previous study, Mini-Cog scores were calculated retrospectively by combining the results of the CDT and the recall task of the MMSE, using a different word combination (bicycle, horse, apple) and clock time (20 to 8) in part of the sample; this may have led to an underestimation of the test’s usefulness.

Both the Mini-Cog and the CDT also present other limitations. Firstly, they have a narrow score range (0-5 for the Mini-Cog and 0-7 for the CDT), which may favour ceiling or floor effects, as observed in Figs. 1 and 2. Furthermore, and more importantly, both tests require minimum graphomotor skills, and are therefore unsuitable for illiterate individuals or those with a low education level; this may explain why the diagnostic usefulness of both tools is limited in individuals who had not completed primary education. These tools should therefore not be used in this population group. This is consistent with the results of other studies evaluating the performance of the Mini-Cog in samples of individuals with low education levels.48,49

The main strength of these tools is their brevity. In our study, the maximum completion time was 266 seconds, and 95% of participants completed the Mini-Cog in less than 3 minutes (95th percentile: 178.2 seconds); in fact, mean (SD) completion time for patients with cognitive impairment was less than 2 minutes (119.4 [36.3]). These results are very similar to those reported in a study including individuals attended at a primary care consultation,50 who completed the Mini-Cog in a mean time of 118 (45) seconds, with no participant requiring longer than 5 minutes.

One of the strengths of this study is the large size and naturalistic character of the sample, since we systematically included all individuals attended at a neurology clinic, regardless of the reason for consultation. This recruitment method limits the risk of selection bias and increases the external validity of our results. Its weaknesses include the fact that controls did not undergo a formal cognitive assessment; presence of cognitive impairment was determined based on the clinical history and Fototest results.26 Though valid, this tool cannot rule out the presence of false negatives, making it difficult to discriminate between patients with and without cognitive impairment. The risk of false positives was not a concern since all participants underwent a formal cognitive assessment. Finally, the functions of the neurology clinic where the study was conducted fall between those of a unit specialising in cognitive impairment and those of a general neurology consultation, which limits the applicability of our results to other settings, such as primary care or the general population.

In conclusion, the Mini-Cog has greater diagnostic usefulness than the CDT in screening for cognitive impairment in neurology consultations, but is unsuitable for the assessment of individuals with low levels of education. The test’s simplicity and speed of use make it particularly useful for application in combination with other brief cognitive tests.2

Conflicts of interestC. Carnero Pardo created the Fototest and has received professional fees for academic and consulting activities for Nutricia, Schwabe Farma Ibérica, Biogen, Piramal, Janssen Cilag, Pfizer, Eisai, Esteve, Novartis, Lundbeck, and Grunenthal.

Under the terms of its Creative Commons licence, Fototest may be used and distributed for non-commercial purposes provided that it is not modified and its authorship is explicitly acknowledged.

Please cite this article as: Carnero-Pardo C, Rego-García I, Barrios-López JM, Blanco-Madera S, Calle-Calle R, López-Alcalde S, et al. Evaluación de la utilidad diagnóstica y validez discriminativa del Test del Reloj y del Mini-Cog en la detección del deterioro cognitivo. Neurología. 2022;37:13–20.

An interim analysis of this study was presented orally at the 70th Annual Meeting of the Spanish Society of Neurology.