Anisocoria is a pupillary disorder and occasionally a warning sign in the emergency department and outpatient clinics. Multiple aetiologies have been described, both severe and benign, and the condition represents a diagnostic challenge that generally requires further testing.1,2 Benign episodic unilateral mydriasis (BEUM) is an infrequent disease whose aetiology is poorly understood, and causes anisocoria secondary to autonomic nervous system dysfunction, frequently associated with migraine with aura.3,4 We present the case of a patient with BEUM in the absence of headache. We describe the clinical analysis prior to diagnosis, which may be very useful for avoiding unnecessary studies and establishing a diagnosis earlier.

Our patient was a 23-year-old woman with no relevant history, who presented sudden onset of photophobia and left pupillary dilation. The episode lasted approximately 5 minutes, but was repeated several times per day over the course of a week. She did not report headache, changes in visual acuity, eye pain, or double vision. Three months later, she noticed that her left pupil was dilated, with altered morphology and hyporeactivity to light stimuli. On this occasion, dilation lasted approximately 2 hours, was not accompanied by headache or other symptoms, and was not associated with any trigger factor.

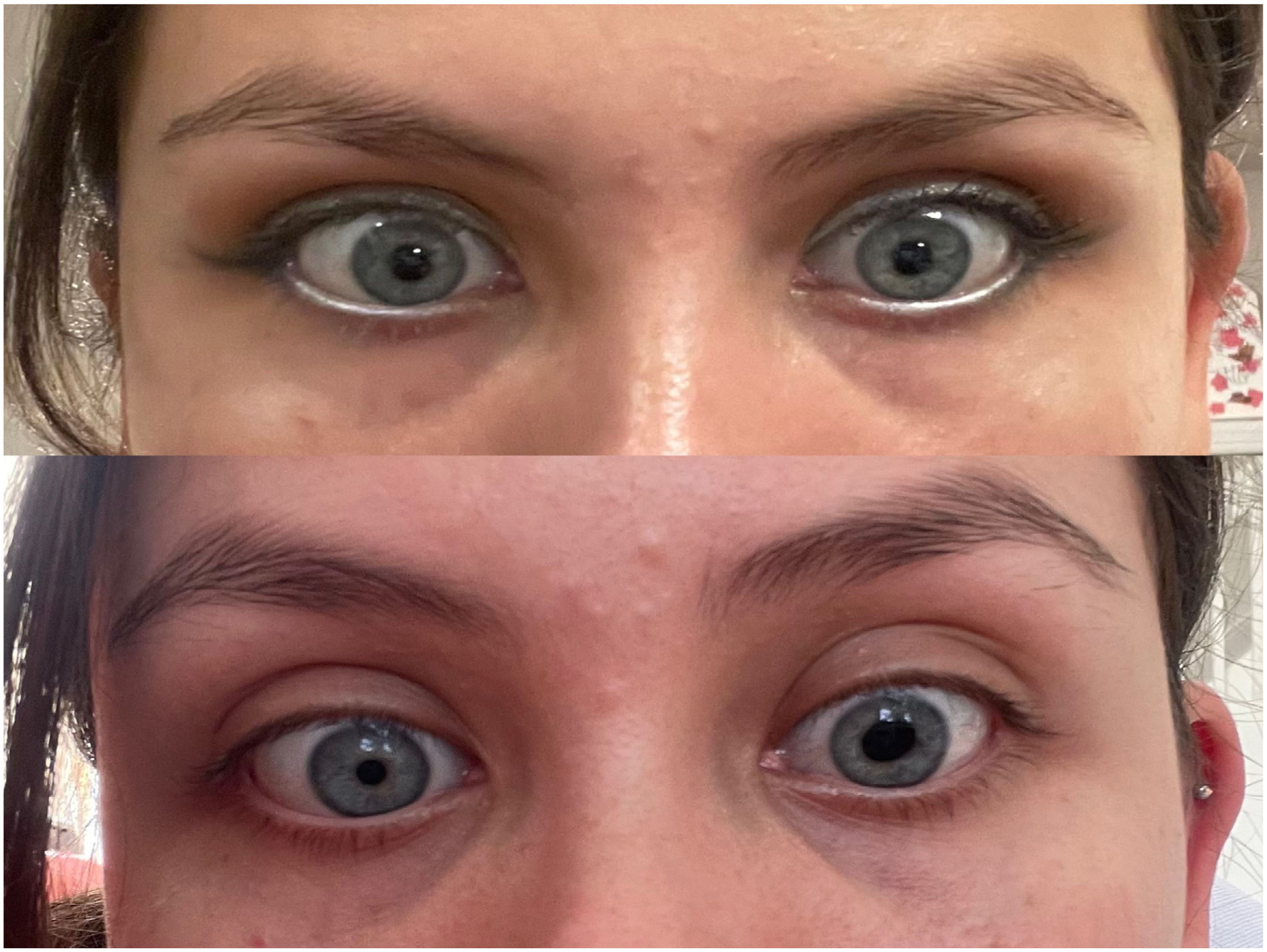

The patient was assessed on numerous occasions at the emergency department and the outpatient neurology and neuro-ophthalmology clinics. She was asymptomatic at the time of the assessments, and no abnormalities were observed in the neurological examination. A non-contrast brain MRI study and MRI angiography yielded normal results. As no abnormalities were observed in the clinical examination or additional studies, we considered that the patient may present BEUM, requiring no treatment. Fig. 1 shows a comparison between the patient’s pupils in normal conditions and during an episode of left BEUM.

We present the case of a patient with episodes of left episodic mydriasis without associated headache. In the clinical assessment of pupillary disorders, we should evaluate the direct response when directing light at the pupil, the consensual response after directing light at the contralateral pupil, and accommodation.5 Pupillary control is regulated by the autonomic nervous system: pupillary contraction is mediated by parasympathetic activation of the sphincter muscle of the pupil and dilation by sympathetic activation of the iris dilator muscle.6 The accommodation reflex consists in pupillary contraction, accommodation of the ciliary muscle, and eye convergence; it is activated by visual signs transmitted through the parasympathetic pathway to the visual cortex when looking at approaching objects.7

From a topographic perspective, pupillary anomalies may be caused by peripheral or central lesions, sympathetic or parasympathetic lesions, or alterations to the iris muscle or visual pathways.8 Pupillary anomalies may be bilateral or unilateral, in which case anisocoria or pupil asymmetry are observed, as in the case of our patient. In these cases, the light reflex of the affected pupil must be assessed. If the mydriatic pupil reacts poorly to light, anisocoria is less marked with low light, and the afferent visual system is normal, then it is likely that there is a defect in efferent parasympathetic innervation. If anisocoria is greater with low light or in darkness, then the defect involves the sympathetic innervation of the pupil. In cases of anisocoria with normal pupillary light reflex in both eyes, the patient probably presents physiological anisocoria.6 In these cases, the difference in pupil size is the same with bright or low light, and patients generally report the anomaly in the long term. Our patient reported sluggish pupillary light reflex during episodes of mydriasis.

Anisocoria due to sympathetic dysfunction manifests almost exclusively as Horner syndrome. It commonly presents as a triad of palpebral ptosis, miosis, and ipsilateral anhidrosis.5 Miosis is caused by loss of sympathetic innervation of the iris dilator muscle, which causes anisocoria that is more evident in the dark. Despite anisocoria, the patient did not present miosis, palpebral ptosis, or alterations in sweating function, which makes Horner syndrome unlikely.

Parasympathetic dysfunction may be associated with third nerve palsy, iris lesions, lesions to the ciliary ganglion or short ciliary nerves, or may be linked to the use of a drug.6 Third nerve palsy may manifest with lesions to the efferent parasympathetic pathway, resulting in unilateral mydriasis.8 Although we were aware of a decreased pupillary reaction to light during the patient’s episodes of mydriasis, her neurological examination and neuroimaging studies yielded normal results, which ruled out left third cranial nerve palsy. Lesions to the ciliary ganglion and short ciliary nerves manifest as tonic pupil due to deficient or absent reaction to light stimulus, with slow contraction to prolonged near effort.8 This lesion has been associated with peripheral neuropathy, generalised dysautonomia, or Adie tonic pupil in healthy individuals.9 Our patient presented no history or examination findings suggesting neuropathy or dysautonomia.

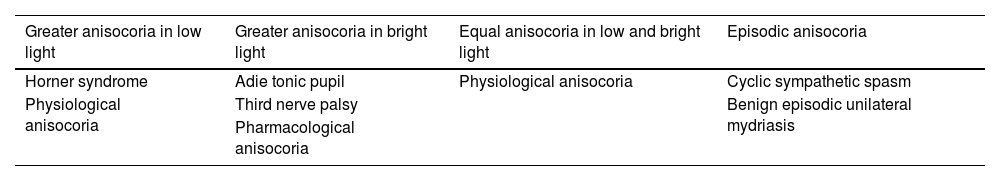

Periodic pupillary phenomena are rare, and are mediated by abnormal sympathetic or parasympathetic activity.8 Excess parasympathetic activity may manifest with periodic pupillary contractions, such as cyclic oculomotor palsy, ocular neuromyotonia, and rhythmic pupillary oscillations. Intermittent unilateral mydriasis may manifest during or after a seizure, in association with migraine, in recurrent painful ophthalmoplegic neuropathy, in trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias, or as a transient phenomenon in healthy young adults.4,10–13Table 1 shows the possible causes of anisocoria according to the light reflex in the affected pupil.

Causes of anisocoria according to the light reflex in the affected pupil.

| Greater anisocoria in low light | Greater anisocoria in bright light | Equal anisocoria in low and bright light | Episodic anisocoria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Horner syndrome | Adie tonic pupil | Physiological anisocoria | Cyclic sympathetic spasm |

| Physiological anisocoria | Third nerve palsy | Benign episodic unilateral mydriasis | |

| Pharmacological anisocoria |

In 1955, Jacobson described the clinical characteristics of the syndrome of neurologically isolated episodic unilateral mydriasis, which was not associated with neurological disorders.1 Jacobson associated this entity with a parasympathetic insufficiency or sympathetic hyperactivity. A case series published in 2015 described the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patients with episodic benign mydriasis at a Spanish hospital.14 Mydriasis manifested unilaterally in the majority of cases, and more than half of patients showed no associated symptoms, although the disorder is usually associated with episodes of migraine with aura or ophthalmoplegic migraine.4,15,16

BEUM should be suspected in healthy young patients presenting no abnormalities in the neurological examination other than mydriatic pupil, or even no abnormalities at all. Comprehensive history-taking and neurological and ophthalmological examination are important, as well as additional studies to rule out other diseases when necessary. Once secondary causes have been ruled out, BEUM does not require further study or specific treatment.