Moyamoya disease (MMD) is a rare cerebrovascular disease which manifests almost exclusively in Asian populations, increasing risk of stroke due to progressive stenosis of the internal carotid artery and its main branches.

We present the case of a 29-year-old woman from Badalona (Spain), not of Asian descent, who smoked 6 to 7 cigarettes/day and was independent in the activities of daily living. Her personal history included arterial hypertension and MMD diagnosed at 12 years.

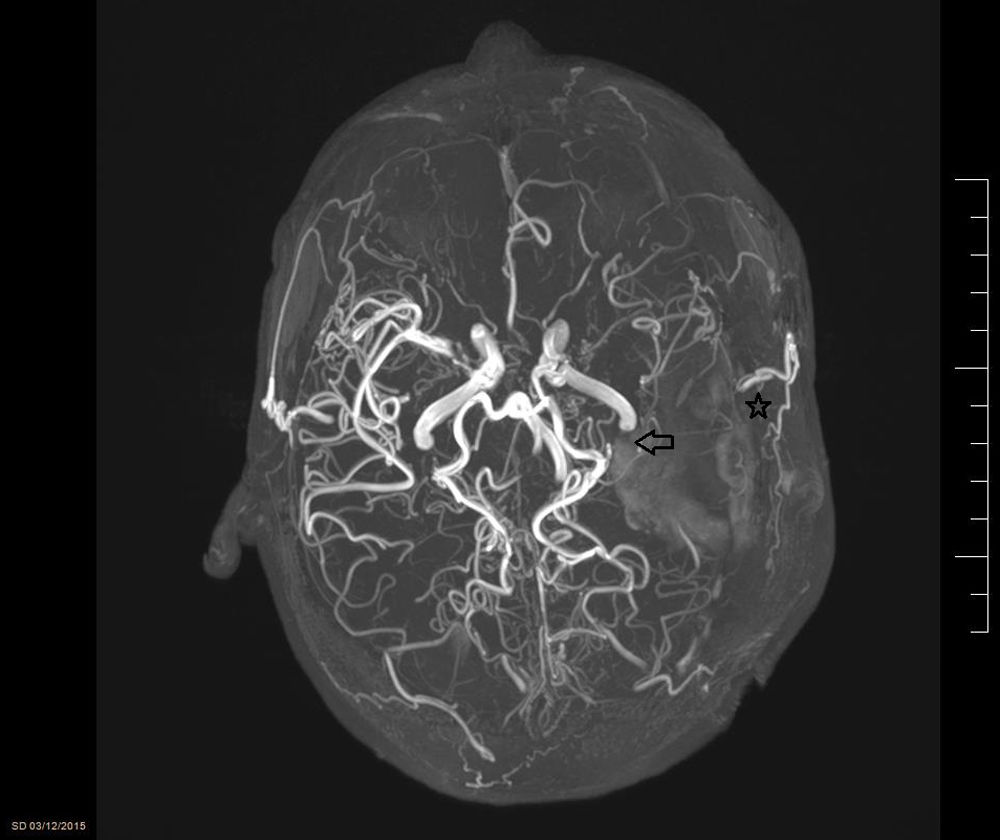

As a result of MMD, the patient presented subarachnoid haemorrhage at the age of 12, intraventricular haemorrhage at 27, and seizures and numerous transient ischaemic attacks in the left hemisphere. She was followed up periodically with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), and intracranial angiographies. The last MRI scan, performed after the intraventricular haemorrhage, revealed distal stenosis of both internal carotid arteries (ICA), which had remained stable with regards to previous follow-up studies, critical stenosis of the left middle cerebral artery (MCA) in the M1 segment, stable stenosis of the right MCA, and hypertrophy of the vessels at the base of the cranium. Due to progression of the lesion involving the left MCA, an extra-intracranial bypass was scheduled.

While awaiting surgery, the patient experienced an episode of sudden headache with anisocoria due to left mydriasis, facial droop, hyperextension of the left side of the body, and decreased level of consciousness (GCS 4), requiring orothracheal intubation. A brain CT scan (Fig. 1) showed a large intraparenchymal haematoma in the left temporoparietal region (51×50×38mm) with mass effect and deviation of intracranial structures. The patient underwent an emergency craniectomy, with evacuation of the haematoma, and was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for postoperative monitoring. During her ICU stay, her neurological symptoms slightly improved, whereas she developed generalised spasticity, continued to display a low level of consciousness (GCS 8), and presented disorientation and status epilepticus, which was resolved with antiepileptics. Follow-up radiological studies (CT and MRI) showed that brain structures were centred and revealed signs of subacute ischaemia in the left basal frontal area. Despite medical treatment, the patient was transferred after a 57-day ICU stay to an admission ward with a tracheostomy cannula, and subsequently to a social care centre, with practically no neurological improvement.

MMD was first defined in 1957 by 2 Japanese doctors (Takeuchi and Shimizu). The disorder is characterised by progressive occlusion of the ICA at its most terminal end, causing the appearance of a network of anomalous collateral vessels at the base of the cranium (Fig. 2). The name of MMD comes from the appearance of the vessels in the radiological studies (moyamoya means “puff of smoke” in Japanese). The disease is relatively frequent in the Asian population, especially in Japan and Korea (incidence of 0.54 and 0.94/100000 inhabitants, respectively, according to the latest studies1); in other regions, its incidence is practically anecdotal (0.086/100000 inhabitants in a US population study).

Although its cause remains unknown, the disease has recently been associated with mutations in the ACTA2 protein,2 encoded by a chromosome 10 gene, and is responsible for an anomalous proliferation of the muscles of the intimal layer of the intracranial vessels, which would cause progressive vessel stenosis and the appearance of such arterial malformations as microaneurysms. Furthermore, it is believed to follow a pattern of familial inheritance: 10% of individuals with MMD have family history of the condition. Mutations have been described in different chromosomes, with the RNF213 gene (chromosome 17) being the strongest susceptibility gene: 95% of patients affected by MMD with a family history present the mutation, as do 80% of patients with sporadic MMD in East Asian countries (the mutation has been detected in only 1.8% of healthy controls).2 Female sex is a risk factor for MMD, and faster progression has been observed in women.3,4

There are 2 peaks in the incidence of the disease, at paediatric age (5-15 years) and at 30 to 40 years.1 In general, paediatric patients with MMD present ischaemic alterations; the most frequent are transient ischaemic attacks of the anterior territory, especially due to MCA involvement (posterior territory involvement is infrequent and associated with poorer prognosis), followed by cerebral ischaemic strokes. Symptoms are caused by the decreased arterial flow in the affected vessels; several trigger factors have been identified, including hyperventilation, stress, fatigue, and dehydration. In adult patients, however, MMD is usually associated with intracranial haemorrhages.4 Most of these events are believed to be caused by rupture of the collateral vessels at the base of the cranium and arterial micro-aneurysms, resulting in intracranial haemorrhages, and less frequently subarachnoid haemorrhages.

Diagnosis of MMD is established by angiography findings confirming a steno-occlusive change in at least one ICA and/or its branches. In any case, the complications associated with this diagnostic test, its low sensitivity for detecting the formation of collateral vessels at the base of the cranium, and recent advances in MRI and CT mean that there is no need to perform invasive techniques to establish a definite diagnosis of MMD.

The only treatments with demonstrated positive results are direct and indirect revascularisation.5 Direct revascularisation consists of the formation of an extra-intracranial bypass between the superficial temporal artery and the MCA (when symptoms affect the posterior territory, the bypass is performed between the occipital artery and the posterior cerebral artery). Indirect revascularisation consists of implanting vascularised tissue (normally temporal muscle) into the dura mater to take advantage of the disease's tendency towards angiogenesis to perfuse the ischaemic areas. These treatments have been associated with clinical and radiological improvements (unravelling the tangle of collateral vessels) and increased survival in several retrospective and prospective studies.3,6 Such other treatments as antiplatelet drugs or watchful waiting showed no positive results.3

Please cite this article as: Plans Galván O, Manciño Contreras JM, Coy Serrano A, Campos Gómez A, Toboso Casado JM, Ricart Martí P. Hemorragia intraparenquimatosa por enfermedad de Moyamoya en una paciente caucásica. Neurología. 2019;34:553–555.