Localised scleroderma (LS) is a rare autoimmune disorder that primarily affects the skin and may also affect underlying fatty, muscle, or bone tissue.1 The estimated prevalence of this disease is fewer than 3 cases in 100000 inhabitants.2

LS affects the skin almost exclusively, and with rare exceptions, does not injure internal organs. It is categorised into 5 subtypes: circumscribed morphea, linear scleroderma, generalised morphea, pansclerotic morphea, and a mixed subtype.3

Linear scleroderma en coup de sabre (LSCS) is a descriptive term indicating the presence of LS on the frontoparietal face and scalp. This uncommon form of LS mainly occurs in paediatric patients; neurological symptoms, especially epilepsy, are also relatively common in these patients.2,4

We present the case of a 7-year-old male whose state of health was normal until the age of 20 months when he began to show hyperpigmented lesions on the left side of his face (forehead and nose) with progressive atrophy of the skin and underlying tissue in that region. LSCS was diagnosed based on the clinical profile with pathognomonic signs of the linear subtype of scleroderma, and on the criteria for classifying systemic juvenile sclerosis5,6 (Fig. 1).

Six months after onset of the illness, the patient began to experience episodes of right-sided deviation of the eyes and head with episodes of altered consciousness lasting a few seconds, followed by rapid complete recovery (1–2min). He was diagnosed with focal symptomatic epilepsy and started carbamazepine treatment.

When the child was 5 years old, he described vision loss at the onset of seizures. Clobazam was added to his treatment programme, and seizures remain controlled to date.

The neuropsychological study performed when the patient was 7 years old showed an intellectual level in the lower normal range (WISC-R: performance IQ 63; verbal IQ 84; full scale IQ 71).

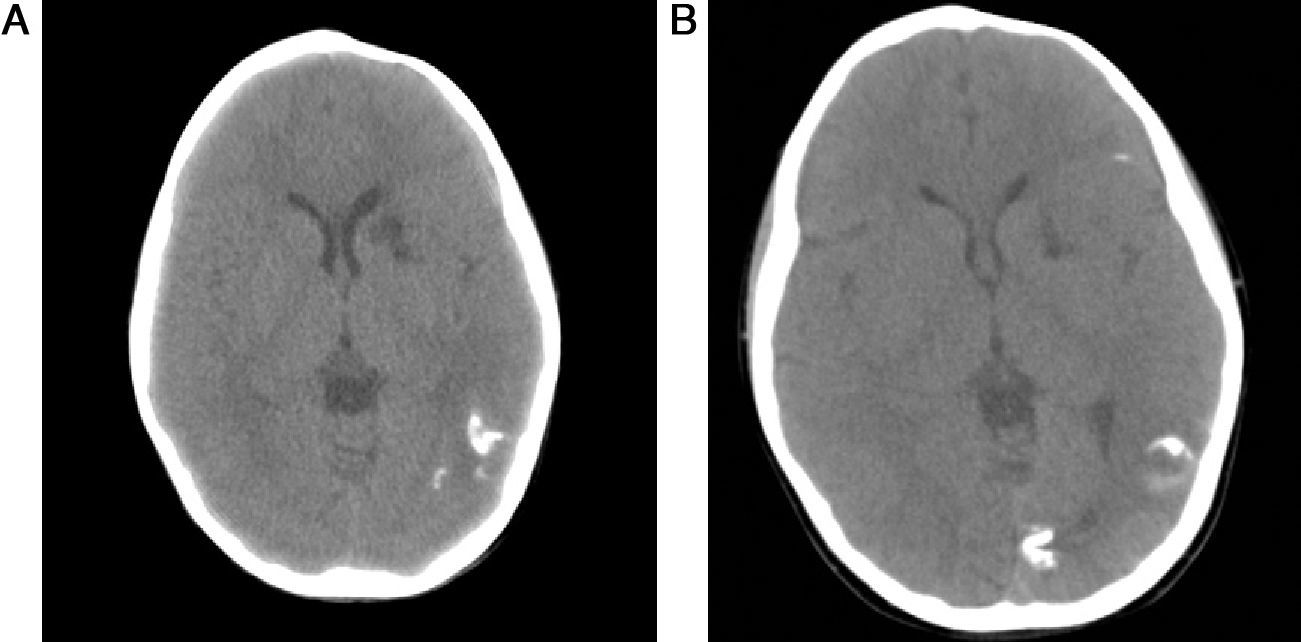

Cranial CT scans completed when the patient was 4 and 7 years old showed an increase in calcification in the left brain hemisphere and a hypodense area in the head of the left caudate nucleus that suggested an old cerebral infarct (Fig. 2).

Multiple neurological manifestations may be associated with LSCS; of these, focal epileptic seizures are the most common.7–13

Changes detected in CT studies tend to be ipsilateral to skin lesions and may include the following: thinning or depression of the external diploë, focal or hemispheric cerebral atrophy, and intracranial calcifications.2,6,14

Cerebral lesions caused by infarct are rare in linear scleroderma, so the presence of a cerebral infarct in our patient deserves mention. There are few reports of cerebral infarcts occurring in patients with LSCS.2

Calcified intracranial lesions may be produced by an inflammatory process in cerebral blood vessels. Interestingly enough, these lesions arise on the same side as the skin lesions, and there is still no reliable scientific explanation for this phenomenon. The autoimmune hypothesis has the best evidence in its favour. It is based on reports of findings from cerebral biopsies showing inflammatory changes in the cerebral parenchyma, and sometimes in blood vessels and the meninges as well.15

In the case we present, we find evidence that the disease remains active; intracranial calcifications have continued growing slowly and gradually, despite use of correctly dosed immunosuppressants. Even considering the course of the disease and the presence of extracutaneous neurological signs, the patient has never met all the diagnostic criteria for systemic juvenile sclerosis.5

Please cite this article as: Garófalo Gómez N, et al. Esclerodermia lineal en golpe de sable y epilepsia. A propósito de un caso infantil. Neurología. 2012;27:449–51.