We present the case of an adolescent girl aged 17 with no relevant medical history who was assessed in our epilepsy unit due to a 2-year history of repeated syncope, preceded by pallor and discomfort. There were no abnormal movements during episodes and the patient recovered in minutes with no subsequent confusion or loss of sphincter control. Episode frequency was variable with a maximum of 2 per week. Some occurred during physical exertion. She sometimes reported palpitations while standing or walking. She had also experienced repeated sprains.

The patient was examined by the cardiology and neurology departments; she had visited the emergency department on 14 previous occasions and been admitted 6 times, including admission to the intensive care unit once due to suspected epilepsy. At that time, a differential diagnosis was performed for psychogenic seizures and epilepsy. The patient was treated with 2g levetiracetam/24hours with no signs of improvement. Test results were normal, except for isolated sinus tachycardia that was detected with an implantable loop recorder, and left-sided hippocampal malrotation detected by brain MRI. It was on this basis that doctors suspected epilepsy.

The examination identified venous pooling in the lower limbs while standing, keloid where the implantable loop recorder had been placed, and joint hypermobility with a score of 5/9 on the Beighton scale (Fig. 1). The patient met Brighton diagnostic criteria for joint hypermobility (1 major and 2 minor criteria).

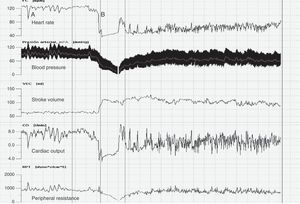

Doctors opted for a tilt table test and non-invasive haemodynamic monitoring with a Task Force® Monitor (Fig. 2). We observed low blood pressure (BP) at baseline and postural tachycardia with a heart rate above 120bpm and cardioinhibitory syncope associated with vasodepressor response and a drop in peripheral resistance, together with an increase in stroke volume. All findings were compatible with neurally mediated syncope. Doctors began treatment with fludrocortisone dosed at 0.1mg/day and non-pharmacological therapy; syncope episodes ceased completely.

Postural tachycardia syndrome has an estimated prevalence of 170 per 100000 individuals. It is more common in women (5:1) and at ages between 20 and 40; aetiopathogenesis is heterogeneous. The condition essentially amounts to a variable degree of intolerance to orthostasis with the addition of symptoms secondary to hypoperfusion, such as difficulty concentrating, neck or thoracic pain due to tissue hypoperfusion, and symptoms of sympathetic hyperactivity with palpitations or tremor.1 This syndrome is closely linked to repeated episodes of neurally mediated syncope.2 Diagnostic criteria are heart rate increase of 30bpm (>40bpm in patients aged 12 to 19 years) when standing or walking or on a tilt table without orthostatic hypotension, or heart rate above 120bpm with no baseline arterial hypotension.3 Non-invasive haemodynamic monitoring associated with BP monitoring over 24hours is very useful for evaluating the condition.

Physical examination frequently reveals oedema and venous pooling in the lower limbs resulting from vasoconstriction disorders.4

Type 3 Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (hypermobility syndrome) is related to postural tachycardia syndrome.5 It is characterised by presence of joint hypermobility (although this sign may be absent), skin abnormalities, and other signs.6 Diagnosis is clinical; doctors use the Beighton score7 and the Brighton diagnostic criteria8 and rule out other potential entities.

Treatments may be pharmacological or non-pharmacological (increasing fluid and sodium intake, posture therapy, and cognitive behavioural therapy). Pharmacological treatments include 2 major groups. The first is typically used in cases with low baseline BP (fludrocortisone9 and midodrine10). The second is for patients with normal BP or arterial hypertension (beta-blockers and pyridostigmine).11 Drugs from both of the above groups may be used in combination on a case-by-case basis.

These disorders are prevalent, underdiagnosed, and have a major impact on quality of life. However, patients may benefit from correct diagnostic and therapeutic management provided by specialists, and therefore avoid iatrogenic effects of testing and treatments and periodic visits to doctors and the emergency department. As a screening method, patients or their family members may measure BP and heart rate in the decubitus and standing positions. Proper management of these patients will require additional training for neurologists and the creation of specialised units.

Please cite this article as: Berganzo K, Tijero B, Zarranz JJ, Gómez-Esteban JC. Síndrome de taquicardia postural ortostática, síncopes autonomomediados e hiperlaxitud articular: a propósito de un caso. Neurología. 2014;29:447–449.