Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) is the leading cause of death in patients with epilepsy. Most studies concerning this issue have been conducted in central and northern European countries and the United States. We conducted an epidemiologic study of SUDEP at our hospital's epilepsy unit.

MethodsThis retrospective cohort study included all epileptic patients aged ≥14 years, regardless of epilepsy severity, who were treated at the outpatient epilepsy unit of our hospital between 2000 and 2013. The study included 2309 patients. Deceased patients were identified using civil records. The cause of death was obtained from death certificates, autopsy reports, hospital reports, general practitioner records, and witnesses of the event. We calculated the incidence and proportional mortality of SUDEP based on our data.

ResultsWe identified 7 cases of definite SUDEP (2 patients with SUDEP plus), one case of probable SUDEP, and one case of possible SUDEP. Considering only cases of definite SUDEP, incidence was estimated at 0.44 cases per 1000 patient-years and proportional mortality at 4.6%. Mean age of patients with definite SUDEP was 38.14 years; 4 were men and 3 were women. Most deaths occurred while patients were in bed and were therefore unwitnessed. Epilepsy in these patients was either remote symptomatic or cryptogenic. All patients but 2 had generalised seizures. None of the patients was in remission.

ConclusionsSUDEP incidence and proportional mortality rates in our study are similar to those reported by population studies. This may be due to the fact that we did not select patients by severity. Risk factors for SUDEP in our sample are therefore consistent with those reported in the literature.

La muerte súbita en epilepsia (SUDEP) es la causa más frecuente de muerte atribuible a la propia enfermedad. Casi toda la información sobre esta entidad procede de estudios realizados en el centro/norte de Europa y Estados Unidos. Presentamos la casuística de SUDEP de la Unidad Médica de Epilepsia de nuestro hospital.

MétodosEstudiamos una cohorte histórica hospitalaria española, sin selección de pacientes por su gravedad, con 2.309 pacientes, de edad ≥14 años, entre enero de 2000 y junio de 2013. La identificación de los fallecidos se realizó a través de los Registros Civiles. Las causas de muerte se establecieron mediante certificados de defunción, autopsias forenses, informes de mortalidad hospitalarios, de médicos de familia y de testigos de los fallecimientos. Calculamos la incidencia y la mortalidad proporcional.

ResultadosIdentificamos 7 casos de SUDEP definitivas (2 SUDEP-plus), uno probable y uno posible. Considerando solo los casos con autopsia, la incidencia es de 0,44/1.000 persona-año; la mortalidad proporcional es del 4,6%. Son 4 varones y 3 mujeres. La edad media es de 38,14 años. Casi todos los fallecimientos ocurrieron sin testigos, en la cama. La etiología de la epilepsia es sintomática remota o criptogénica. Menos 2 pacientes, todos tenían crisis generalizadas. Ninguno estaba en remisión.

ConclusionesPensamos que la incidencia y la mortalidad proporcional de SUDEP de nuestro estudio se asemejan a las encontradas en estudios poblacionales por el carácter escasamente seleccionado de nuestra cohorte. Los factores de riesgo para SUDEP encontrados en nuestros pacientes son concordantes con los reconocidos en la bibliografía.

Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) is considered the most important cause of death directly attributed to epilepsy. Sudden death is more frequent in these patients than in the general population. This, together with the devastating fact that sudden unexpected death typically occurs in young adults, has sparked growing interest in its study in recent decades. SUDEP is defined as sudden, unexpected, witnessed or unwitnessed, nontraumatic, and nondrowning death in patients with epilepsy, with or without evidence of a previous seizure and excluding documented status epilepticus (SE), in which postmortem examination does not reveal a toxicological or structural cause of death.1 Therefore, an autopsy study is needed to establish a definitive diagnosis.

Most studies on SUDEP were conducted in northern and central European countries and in the USA. Southern European countries, and specifically Spain, have produced few studies on SUDEP.2,3 We present the results of our 13.5-year study of cases of SUDEP at our hospital's epilepsy unit.

Patients and methodsPatientsThe patient population has been described in detail elsewhere.4 We included all patients diagnosed with epilepsy and attended on an outpatient basis from 1 January 2000 to 30 June 2013 or to the time of their death, at the epilepsy unit of the neurology department at Hospital Virgen de la Victoria (Málaga). This was the region's only public reference centre for neurological patients during the study period. The unit treats patients aged 14 or older. All patients with suspected epilepsy are assessed, regardless of the severity. In terms of healthcare resources, it is considered a second-level epilepsy care unit.

MethodsThe definitions of epilepsy and seizure type and the aetiological classification used met the criteria of the International League Against Epilepsy,5–7 and are described elsewhere, as well as the method to identify deceased patients,4 which we briefly describe.

Deceased patients were identified using the INFOREG programme developed by the Spanish Ministry of Justice, which connects all digital civil registries in the country. By entering the personal details of every patient in the cohort, we were able to check whether a death certificate was available and whether a forensic autopsy had been conducted. Whenever possible, we determined the cause of death by obtaining copies or transcripts of the original death certificates, where the cause was stated. We gathered detailed information on all forensic autopsies performed from the legal medicine institutes. All medical and legal documents were accessed with the relevant authorisations from the judges responsible for the civil registries. We consulted the reports on in-hospital mortality, where applicable. We obtained direct information from primary care physicians and emergency medical teams when patients had died in their homes. We identified and analysed the cases meeting diagnostic criteria for SUDEP.

We used the definition and classification of SUDEP proposed by Nashef et al.1 in 2012, which is widely cited in the studies on this subject. Diagnosis of “definite SUDEP” is established when all criteria are met and there is a postmortem examination; “probable SUDEP” meets all criteria but lacks postmortem data; “possible SUDEP” is established when SUDEP cannot be ruled out, but there is insufficient evidence regarding the circumstances of the death and no postmortem report available. “Near SUDEP” is defined as cases in which cardiorespiratory arrest meeting the conditions for SUDEP diagnosis was reversed by resuscitation efforts, with subsequent survival for more than one hour. “SUDEP plus” refers to those cases fully complying with the definition of SUDEP, but with evidence of a circumstance that may have contributed to death (e.g., coronary insufficiency with no evidence of myocardial infarction in the postmortem examination).

Statistical analysisSUDEP incidence was calculated as the number of cases per 1000 person-years in follow-up. Proportional mortality was calculated as the percentage of deaths caused by SUDEP.

ResultsOur cohort included 2309 patients (1264 men, 1045 women). The study period was 13.5 years, with a mean (SD) follow-up time of 6.9 years (3.8). This amounted to a total of 15865 person-years in follow-up. One hundred and fifty-two patients died; we were unable to determine the vital situation (living or deceased) of 35 patients.

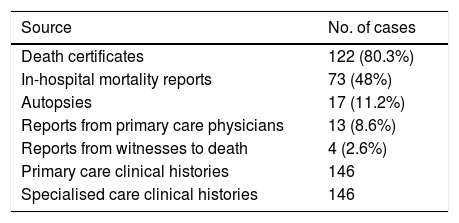

Cause of death was established in 146 cases; these are shown in Table 1.

Sources of information to establish the cause of death.

| Source | No. of cases |

|---|---|

| Death certificates | 122 (80.3%) |

| In-hospital mortality reports | 73 (48%) |

| Autopsies | 17 (11.2%) |

| Reports from primary care physicians | 13 (8.6%) |

| Reports from witnesses to death | 4 (2.6%) |

| Primary care clinical histories | 146 |

| Specialised care clinical histories | 146 |

We identified 9 deaths associated with SUDEP: 7 definite SUDEP (2 SUDEP plus), one probable near-SUDEP, and one possible SUDEP. These represent 4.6% of all deaths if we exclusively consider cases with postmortem examinations (definite SUDEP). This translates into an incidence of 0.44 per 1000 person-years. If we include cases without postmortem analysis (probable and possible SUDEP) in the analysis, the proportional mortality increases to 5.9% and incidence to 0.56 per 1000 person-years.

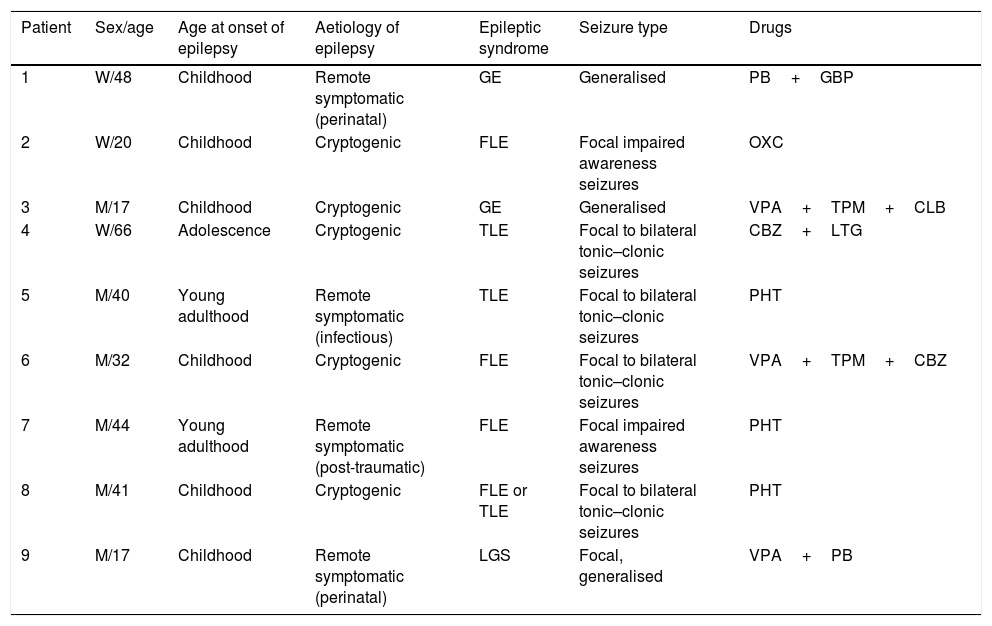

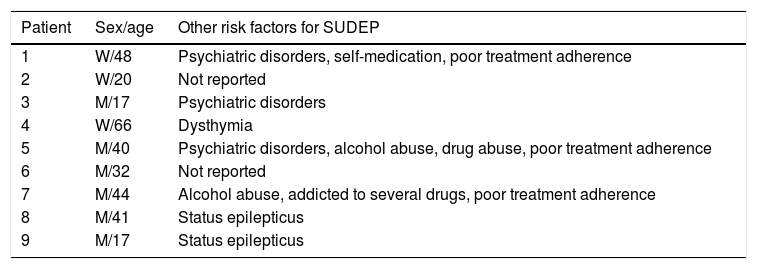

The demographic characteristics and clinical data of the patients whose death was related to SUDEP are listed in Tables 2 and 3. Postmortem examination data were available in 7 cases (4 men and 3 women; mean age, 38.14 years). None of these patients presented seizures in remission. Seizure frequency ranged between one or more per day and 3 per year; only one patient had presented no seizures in the last year. No specific mention was made in the reports from the epilepsy clinic of whether patients or their relatives were informed of the possibility of SUDEP.

Cases related to SUDEP.

| Patient | Sex/age | Age at onset of epilepsy | Aetiology of epilepsy | Epileptic syndrome | Seizure type | Drugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | W/48 | Childhood | Remote symptomatic (perinatal) | GE | Generalised | PB+GBP |

| 2 | W/20 | Childhood | Cryptogenic | FLE | Focal impaired awareness seizures | OXC |

| 3 | M/17 | Childhood | Cryptogenic | GE | Generalised | VPA+TPM+CLB |

| 4 | W/66 | Adolescence | Cryptogenic | TLE | Focal to bilateral tonic–clonic seizures | CBZ+LTG |

| 5 | M/40 | Young adulthood | Remote symptomatic (infectious) | TLE | Focal to bilateral tonic–clonic seizures | PHT |

| 6 | M/32 | Childhood | Cryptogenic | FLE | Focal to bilateral tonic–clonic seizures | VPA+TPM+CBZ |

| 7 | M/44 | Young adulthood | Remote symptomatic (post-traumatic) | FLE | Focal impaired awareness seizures | PHT |

| 8 | M/41 | Childhood | Cryptogenic | FLE or TLE | Focal to bilateral tonic–clonic seizures | PHT |

| 9 | M/17 | Childhood | Remote symptomatic (perinatal) | LGS | Focal, generalised | VPA+PB |

CBZ: carbamazepine; CLB: clobazam; FLE: frontal lobe epilepsy; GBP: gabapentin; GE: generalised epilepsy; LGS: Lennox–Gastaut syndrome; LTG: lamotrigine; M: man; OXC: oxcarbazepine; PB: phenobarbital; PHT: phenytoin; SUDEP: sudden unexpected death in epilepsy; TLE: temporal lobe epilepsy; TPM: topiramate; VPA: valproate; W: woman.

Additional risk factors for SUDEP in our series.

| Patient | Sex/age | Other risk factors for SUDEP |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | W/48 | Psychiatric disorders, self-medication, poor treatment adherence |

| 2 | W/20 | Not reported |

| 3 | M/17 | Psychiatric disorders |

| 4 | W/66 | Dysthymia |

| 5 | M/40 | Psychiatric disorders, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, poor treatment adherence |

| 6 | M/32 | Not reported |

| 7 | M/44 | Alcohol abuse, addicted to several drugs, poor treatment adherence |

| 8 | M/41 | Status epilepticus |

| 9 | M/17 | Status epilepticus |

M: man; SUDEP: sudden unexpected death in epilepsy; W: woman.

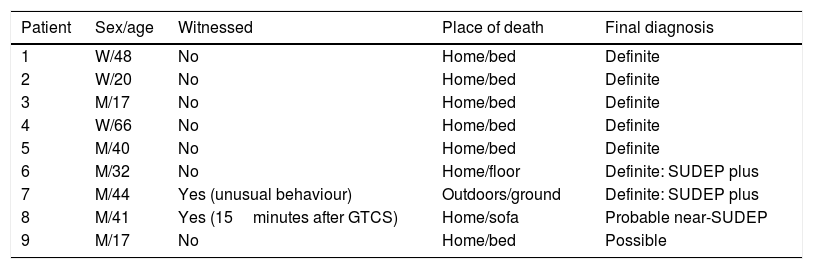

Regarding the circumstances of death (Table 4), 7 patients died at home. Almost all were found in bed; only one was in a prone position. One patient died at hospital after being resuscitated following a cardiac arrest that occurred 15minutes after presenting a generalised tonic–clonic seizure in his home.

Circumstances surrounding death.

| Patient | Sex/age | Witnessed | Place of death | Final diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | W/48 | No | Home/bed | Definite |

| 2 | W/20 | No | Home/bed | Definite |

| 3 | M/17 | No | Home/bed | Definite |

| 4 | W/66 | No | Home/bed | Definite |

| 5 | M/40 | No | Home/bed | Definite |

| 6 | M/32 | No | Home/floor | Definite: SUDEP plus |

| 7 | M/44 | Yes (unusual behaviour) | Outdoors/ground | Definite: SUDEP plus |

| 8 | M/41 | Yes (15minutes after GTCS) | Home/sofa | Probable near-SUDEP |

| 9 | M/17 | No | Home/bed | Possible |

GTCS: generalised tonic–clonic seizures; M: man; SUDEP: sudden unexpected death in epilepsy; W: woman.

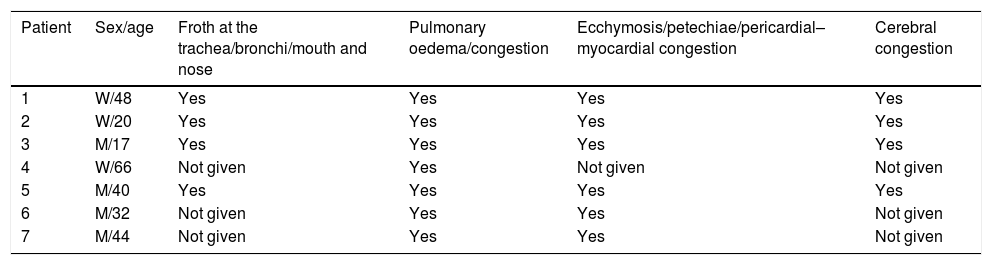

The main postmortem findings are detailed in Table 5. In 3 cases, postmortem examinations revealed signs suggestive of a convulsive seizure: bitten tongue (1), closed fists (2), and pronounced stiffness (1). In the 2 cases of definite SUDEP plus, death was attributed to “ischaemic heart disease” and “severe coronary atherosclerosis,” although acute myocardial infarction was not observed in either case. Drug or medication overdose was ruled out in all cases.

Postmortem findings.

| Patient | Sex/age | Froth at the trachea/bronchi/mouth and nose | Pulmonary oedema/congestion | Ecchymosis/petechiae/pericardial–myocardial congestion | Cerebral congestion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | W/48 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | W/20 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 3 | M/17 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4 | W/66 | Not given | Yes | Not given | Not given |

| 5 | M/40 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 6 | M/32 | Not given | Yes | Yes | Not given |

| 7 | M/44 | Not given | Yes | Yes | Not given |

M: man; W: woman.

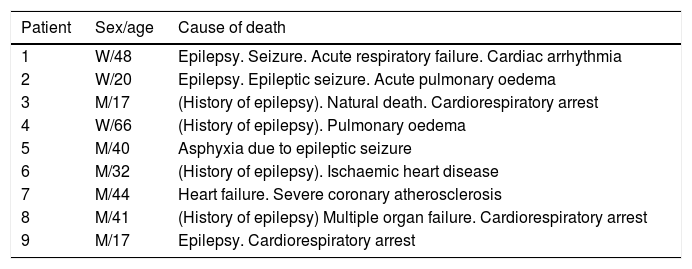

The diagnoses stated in the medical and legal documents are listed in Table 6. Of the 7 cases identified as definite SUDEP, an epileptic seizure was reported as the cause of death in the postmortem reports in 3 cases; it was mentioned under history in 3 cases; no mention of epilepsy was made in one case. In no case was the term “sudden unexpected death” used.

Diagnosed cause of death according to postmortem examination and/or death certificate.

| Patient | Sex/age | Cause of death |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | W/48 | Epilepsy. Seizure. Acute respiratory failure. Cardiac arrhythmia |

| 2 | W/20 | Epilepsy. Epileptic seizure. Acute pulmonary oedema |

| 3 | M/17 | (History of epilepsy). Natural death. Cardiorespiratory arrest |

| 4 | W/66 | (History of epilepsy). Pulmonary oedema |

| 5 | M/40 | Asphyxia due to epileptic seizure |

| 6 | M/32 | (History of epilepsy). Ischaemic heart disease |

| 7 | M/44 | Heart failure. Severe coronary atherosclerosis |

| 8 | M/41 | (History of epilepsy) Multiple organ failure. Cardiorespiratory arrest |

| 9 | M/17 | Epilepsy. Cardiorespiratory arrest |

M: man; W: woman.

Incidence of SUDEP depends on the study population and the methodology used. An extensive review article published by Téllez-Zenteno et al.8 in 2005 reported lower incidence in studies conducted in the general and paediatric populations (0-1.35 cases per 1000 person-years in follow-up) than in selected populations including chronic and more severely affected patients (2.2-10 cases per 1000 person-years in follow-up). A subsequent meta-analysis calculated an incidence of SUDEP in the general population of 1.16 per 1000 person-years among patients with epilepsy.9 The authors conclude that the incidence of SUDEP is underestimated. Other authors have reported the incidence of definite or possible SUDEP at 3.5 per 1000 person-years in a cohort of adult patients with severe epilepsy10; a Scottish study reported an incidence of 2.46 per 1000 person-years in a cohort of patients with chronic epilepsy.10 We found only 2 Spanish studies on SUDEP, both by Morentín et al.2,3: the first, published in 2001, on the incidence and causes of sudden death in patients younger than 36 in Biscay, identified epilepsy as the second leading cause of noncardiac sudden death in that age group; the second study analysed 8 cases of SUDEP that occurred in the authors’ area during the study period. Many researchers report having experienced significant difficulties in the identification of cases of SUDEP.11–13

Our study found a low incidence of SUDEP, which may be attributed to 2 main reasons. Although our study was conducted at a hospital epilepsy unit, care is not limited according to the patient's severity; therefore, we cover the whole spectrum of the disease, providing care also to patients with more benign forms of epilepsy. Therefore, our incidence rate is closer to those reported in studies based on the general population than to rates found in studies conducted in more selected populations. Secondly, we believe that this cause of death is clearly underdiagnosed in our setting. SUDEP normally occurs in the patient's home and patients are not attended by neurologists at the time of death but by emergency medical services or primary care physicians. As these healthcare professionals are often unfamiliar with diagnosis of SUDEP, it is likely that they complete the death certificate attributing death to other causes that they consider reasonable and do not request a forensic autopsy, especially when they know and attend patients and their families. This way, only an investigation similar to that conducted in our study could establish the diagnosis of probable or possible SUDEP, but not definite SUDEP; in some cases, we could not even suspect it. Furthermore, we had to overcome a historical obstacle to access the information contained in death certificates and forensic autopsies, due to the lack of legal provisions supporting research.

Although rare, there are cases in which SUDEP is witnessed; it is almost always associated with seizures (generalised tonic–clonic seizures in the majority of cases), which induce a neurovegetative breakdown, together with the circumstances of occurring at night, the patient being found in a prone position, and a lack of supervision, as demonstrated in the MORTEMUS study.14 Overall evidence suggests that SUDEP mainly affects young adults receiving polytherapy, with frequent seizures, who have not achieved remission and present low antiepileptic drug levels probably due to poor treatment adherence; deceased patients are most frequently found in bed.8,15,16 Other possible risk factors have also been reported (male sex, prolonged duration of epilepsy, early onset, alcohol consumption, and psychoactive drug use, among others). All patients in our series shared at least 2 of these risk factors (most of them several).

Although it is a well-recognised entity in the clinical literature, few published studies review forensic reports of SUDEP. Postmortem studies have revealed pulmonary congestion and oedema as the most consistent findings16; these were observed in all our patients, together with other findings compatible with pathological diagnosis of SUDEP. We were able to confirm that in our setting, forensic specialists do not consider a diagnosis of SUDEP. This makes it impossible to identify and analyse it as a burden associated with epilepsy. The most negative consequence is the lack of planned strategies and necessary resources to prevent these deaths. Neurologists should raise awareness of SUDEP among physicians, especially in primary care, who should be the first to suspect its diagnosis according to patients’ personal history and the circumstances surrounding death. It is necessary also to disseminate this information to legal medicine institutes, so that forensic specialists could establish this cause of death without difficulty, knowing the defined criteria and the compatible postmortem findings. We should stress the need to be rigorous when certifying causes of death, requesting clinical or forensic postmortem examinations when needed. Furthermore, we consider it necessary to design a health policy providing legal and forensic medicine with sufficient human resources to perform as many postmortem examinations as possible to improve our knowledge of SUDEP incidence and prevalence.

Lastly, we should mention that all researchers studying SUDEP acknowledge that neurologists almost systematically do not inform our epileptic patients and their family members about this possible outcome.17 Likewise, in our study we observed a lack of communication with patients on this subject. As professionals attending patients with epilepsy, we should bear this entity in mind and discuss it with our patients and their relatives according to each individual's risk, especially in cases where there is a need to adopt measures to avoid it.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to thank all the civil registries that facilitated our research work, especially civil registry no. 1 and the Legal Medicine Institute of Málaga, without whose help this study would not have been possible.

Please cite this article as: Chamorro-Muñoz MI, López-Hidalgo E, García-Martín G, Rodríguez-Belli AO, Gutiérrez-Bedmar M. Muerte súbita en epilepsia: casuística de una unidad médica de epilepsia española. Neurología. 2020;35:464–469.