A prospective stroke registry leads to improved knowledge of the disease. We present data on the Mataró Hospital Registry.

MethodsIn February 2002 a prospective stroke registry was initiated in our hospital. It includes sociodemographic data, previous diseases, and clinical, topographic, aetiological and prognostic data. We have analysed the results of the first 10 years.

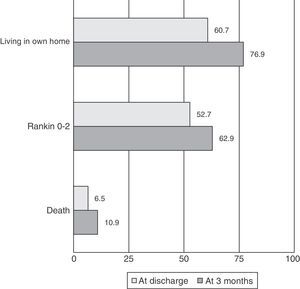

ResultsA total of 2165 patients have been included, 54.1% male, mean age 73 years. The most frequent vascular risk factor was hypertension (65.4%). Median NIHSS on admission: 3 (interquartile range, 1–8). Stroke subtype: 79.7% ischaemic strokes, 10.9% haemorrhagic, and 9.4% TIA. Among ischaemic strokes, the aetiology was cardioembolic in 26.5%, large-vessel disease in 23.7%, and small-vessel in 22.9%. The most frequent topography of haemorrhages was lobar (47.4%), and 54.8% were attributed to hypertension. The median hospital stay was 8 days. At discharge, 60.7% of the patients were able to return directly to their own home, and 52.7% were independent for their daily life activities. After 3 months these percentages were 76.9% and 62.9%, respectively. Hospital mortality was 6.5%, and after 3 months it was 10.9%.

ConclusionsOur patient's profile is similar to those of other series, although the severity of strokes was slightly lower. Length of hospital stay, short-term and medium-term disability, and mortality rates are good, if we compare them with other series.

Un registro prospectivo de ictus permite mejorar el conocimiento de la historia natural de la enfermedad. Presentamos los datos del Registro del Hospital de Mataró.

MétodosEn febrero de 2002 se inició en nuestro hospital el registro prospectivo de pacientes ingresados con un ictus agudo. Se recogen variables sociodemográficas, antecedentes, clínicas, topográficas, etiológicas y pronósticas. Analizamos los resultados obtenidos después de los primeros 10 años de registro.

ResultadosSe han registrado 2.165 pacientes, el 54,1% varones, con una edad media de 73 años. El factor de riesgo más frecuente es la hipertensión (65,4%). Mediana de la NIHSS al ingreso: 3 (rango intercuartílico, 1–8). Un 79,7% han sido infartos cerebrales, un 10,9% hemorragias y un 9,4% AIT. De los isquémicos, la etiología ha sido cardioembólica en el 26,5%, aterotrombótica en el 23,7% y lacunar en el 22,9%. La localización más frecuente de las hemorragias ha sido lobar (47,4%), y se han atribuido a hipertensión el 54,8%. La mediana de la estancia hospitalaria ha sido de 8 días. Al alta, un 60,7% pudieron volver directamente al domicilio y un 52,7% eran independientes para las actividades de la vida diaria. A los 3 meses, las cifras fueron 76,9 y 62,9% respectivamente. La mortalidad intrahospitalaria ha sido del 6,5% y a los 3 meses del 10,9%.

ConclusionesEl perfil de los pacientes en nuestra área no difiere de las otras series, aunque la severidad de los ictus ha sido discretamente menor. Constatamos unas cifras óptimas de estancia hospitalaria y de discapacidad y mortalidad tanto a corto como a medio plazo.

Stroke registries are useful and necessary tools for systematically analysing and studying the epidemiology and the clinical and natural course of these events.1 Since diagnostic and therapeutic management of stroke is evolving constantly, these registries also let doctors assess progression and trends over the years.

The first prospective stroke registries emerged in the 1980s,2,3 but it was not until the late 1990s that different groups started to systematically publish their results. In Spain, we can highlight the Sagrat Cor Hospital of Barcelona Stroke Registry4 and the Barcelona Stroke Registry.5 These first registries, and those that followed them, were mostly hospital-based registries containing descriptive data. Recent publications are describing a rise in another 2 types of registry studies. First, we find multicentre registry studies that may include far higher numbers of patients, but which therefore show more heterogeneity with regard to sociodemographic, diagnostic, and treatment data. Second, we find studies with large recruitment periods that permit trend analysis over different time periods; these trends may document the prevalence of different risk factors, as well as changes in diagnostic and therapeutic approaches (especially in the acute phase), and in the definitive diagnosis itself.

Within the framework of the Spanish Society of Neurology (SEN), the BADISEN registry was created 20 years ago, and in 2010 it was renamed RENISEN. This is a shared registry of hospitals that participate as voluntary members, and it has been used sporadically in some studies.6,7 In 2012, researchers published data from the EPICES study, a prospective registry over 4 non-consecutive months, in which 66 Spanish hospitals participated.8 As far as we know, there are no other published studies on prospective stroke registries that have covered extended periods of time, with the exception of those mentioned above.

We present data extracted from the first 10 years of our hospital stroke registry, along with an analysis of our patients’ vascular risk profile, stroke subtypes, aetiology, topography, outcome, and 3-month follow-up data.

Material and methodsHospital de Mataró is a community hospital located in Maresme, a county situated about 30km north of the city of Barcelona. The hospital provides care to 250000 inhabitants and has 284 beds for acute care patients. Although the hospital does not have an on-call neurologist on a 24-hour basis, our neurology department is available from 8.00 to 19.00 on working days and has 8 admission beds. Our hospital has 5 neurologists on staff, one of whom has specific training in cerebrovascular diseases and is a member of the on-call neurology team at Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, a tertiary referral hospital (TRH). During working hours, a neurologist may be contacted by mobile phone at any time to respond to code stroke and to prescribe systemic fibrinolysis if appropriate. Outside working hours, the telemedicine system Teleictus 2.0, launched in March 2013, allows patients with acute stroke to be treated at our hospital 24hours a day and undergo intravenous fibrinolytic treatment if appropriate. Treatment is always prescribed by a neurologist, either a hospital staff member or a consultant for Teleictus. If the neurologist is absent, the intensive care unit performs the necessary monitoring during the period immediately after administration of the bolus. A close collaboration between our hospital and the TRH enables rapid detection and transfer of candidates for more complex treatments, such as neurointervention or mechanical thrombectomy.

Prior to implementation of the Teleictus 2.0 system, candidates for systemic fibrinolysis treatment were transferred to the TRH if they arrived at the hospital outside the neurologist's working hours. During the period analysed in our study, emergency departments did not consider our hospital a code stroke receiving hospital, and intravenous fibrinolysis was administered to patients who arrived at the hospital during the neurologist's working hours.

Given our hospital's characteristics, stroke patients who might need management and treatment at a tertiary care hospital due to lesion location or characteristics are transferred to the TRH. Such conditions include severe or unstable carotid artery stenosis, large cerebellar lesions with or without mass effect, large lobar haemorrhages in younger patients, and subarachnoid haemorrhages.

Our hospital has a stroke care team consisting of a neurologist responsible for the admitted patient unit and a nursing team specialising in care for acute stroke patients. This team is also responsible for providing a weekly question-and-answer session on stroke for patients and relatives. Our multidisciplinary team also includes a specialised rehabilitation unit, social workers, and professionals from the unit for Interdisciplinary Social Healthcare. The team meets weekly and its members remain in close contact so as to provide the best management for every patient during hospitalisation and in later stages. Our health district contains 4 social health centres with beds that can be used for convalescence, if necessary.

In 2002, we started our own stroke registry which was incorporated into the BADISEN registry, now RENISEN, in 2006. We prospectively entered data from all stroke patients admitted to our hospital through the emergency department, excluding those transferred to other hospitals.

The registry includes personal and sociodemographic details, prior functional state, presence of vascular risk factors, previous treatment, clinical data for current stroke, NIHSS score at admission, neuroimaging data, data from the neurosonology and cardiology studies, stroke type, affected vascular territory in ischaemic strokes and location of haemorrhagic strokes, aetiological classification according to the SEN criteria,9 and, at discharge, hospital stay in days, and scores on NIHSS and modified Rankin Scale (mRS). Three months later, all patients were assessed in outpatient clinics (where this was not possible, telephone interviews were conducted) and place of residence and mRS scores were recorded. A patient is considered to be independent for activities of daily living if his or her mRS is ≤ 2.

In the risk factor analysis, smoking was defined as active tobacco use or having stopped smoking less than 10 years previously. Arterial hypertension (AHT) was defined as the patient reporting a history of systolic blood pressure ≥ 140mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90mmHg, or else receiving antihypertensive treatment. Diabetes mellitus is indicated when it was reported by the patient (fasting glycaemia higher than 120mg/dL measured at 2 different times) or if the patient was receiving antidiabetic treatment. High cholesterol levels were indicated for patients with confirmed plasma levels higher than 220mg/dL or those receiving lipid-lowering drugs.

Ischaemic heart disease corresponds to a well documented acute coronary syndrome; personal history of stroke was defined as past events of symptomatic TIA, cerebral infarct, or intracranial haemorrhage.

Diagnostic and therapeutic decisions were made according to the lead neurologist's best judgement, and always in accordance with the guidelines published by the Spanish Society of Neurology's Cerebrovascular Disease Study Group.10,11

We provide a descriptive analysis of the data collected during the first 10 consecutive years of the registry, from February 2002 to January 2012. A total of 2165 patients were recorded during this period. Since 3-month follow-up data only began to be collected following a systematic and reliable procedure in April 2010, our follow-up analysis only includes patients from the most recent 21-month period (312 patients).

ResultsWe included 2165 patients: 994 women (45.9%) and 1171 men (54.1%). Mean age was 73 years. Strokes were classified as TIA (202, 9.4%), ischaemic strokes (1712, 79.7%), and cerebral haemorrhages (234, 10.9%).

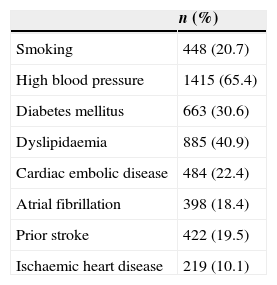

Vascular risk factors in our series are listed in Table 1. The most prevalent factor is AHT with a prevalence of 65.4%, followed by dyslipidaemia at 40.9%. In our study, 19.5% of the patients had suffered a prior stroke, 28.5% were taking antiplatelet drugs, and 7.9%, anticoagulants. Before the stroke, 1879 patients (86.8%) were autonomous for activities of daily living.

The most commonly affected territory in ischaemic stroke was the middle cerebral artery with 798 cases (46.6%), followed by the posterior cerebral artery (10.7%), basilar artery (8%), and anterior choroid artery (6.2%). Cerebellar arteries were the affected territory in 4.8% of ischaemic strokes, and the anterior cerebral artery in 3.2%.

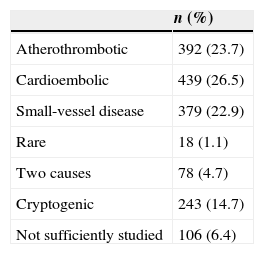

Aetiology of ischaemic strokes is shown in detail in Table 2. Cardioembolic aetiology was identified in 26.5% of the cases, and atherothrombotic or large artery stroke in 23.7%. Small artery stroke accounted for 22.9%, rare origin was identified in 1.1%, coexistence of 2 causes in 4.7%, and cryptogenic origin in 14.7%. Aetiology was not studied in 6.4% of the cases. Carotid stenosis of 70% to 99% was discovered in 3.9% of the patients with ischaemic stroke, and occlusion in 4.4%.

A total of 29 systemic fibrinolyses were performed during the study period, all in the last 4 years.

Cerebral haemorrhageA hypertensive cause was identified in 54.8% of cerebral haemorrhages, while unknown origin or other causes (mainly amyloid angiopathy) were identified in the remaining cases. Nineteen patients (8.1%) were taking oral anticoagulants.

Regarding location, 103 (47.5%) were lobar, 87 (40.1%) were deep (40.1%) and 27 (12.4%) were located in the brain stem and cerebellum.

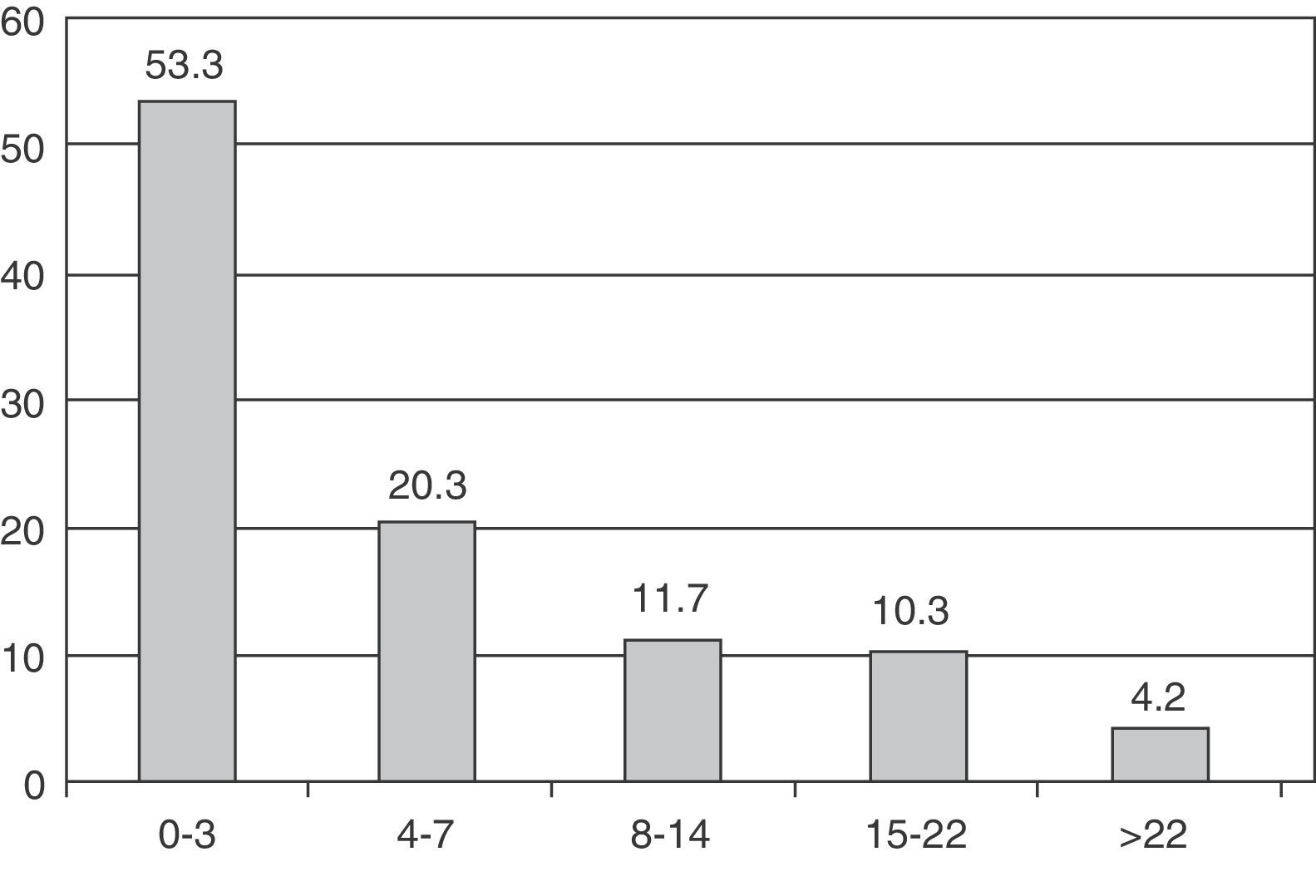

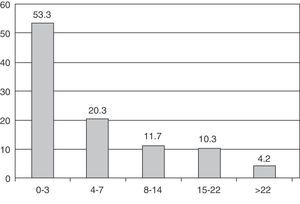

Severity and prognosisMedian NIHSS score was 3 (interquartile range, 1-8) at time of admission. Fig. 1 displays patient distribution according to NIHSS scores at admission. Broken down by stroke subtype, the median NIHSS score for ischaemic stroke patients at admission was 3, compared to 8 for haemorrhagic strokes.

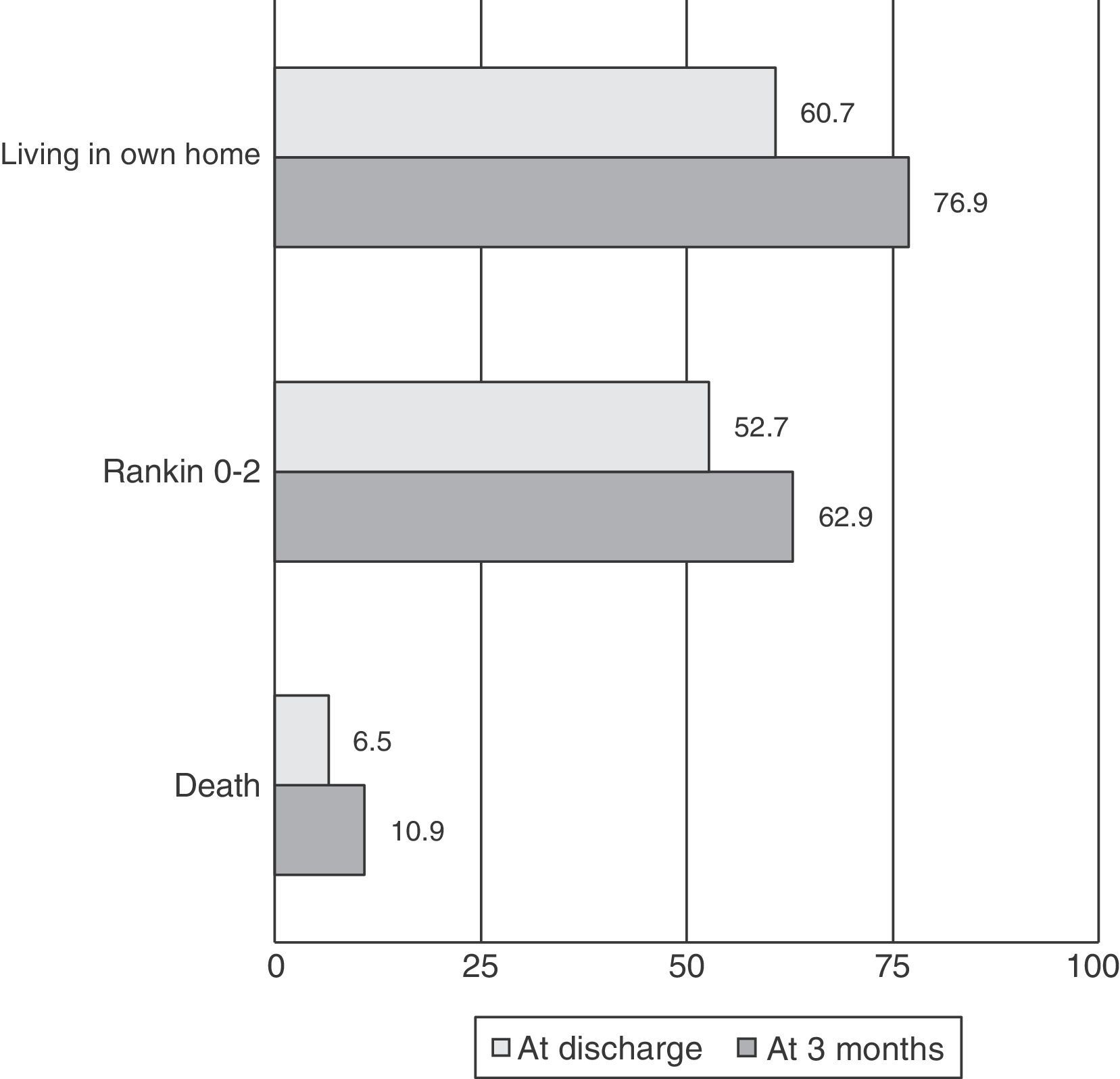

Mean hospital stay was 9 days and the median was 8 days (5-12). After discharge, 60.7% of the patients returned to their homes or to a relative's home and 32.8% were transferred to a social health centre. The in-hospital mortality rate was 6.5%.

Median NIHSS score at discharge was 2 (0-2). Of the patient total, 37.2% had a mRS score of 0-1 and 52.7% were independent for activities of daily living at discharge (mRS 0-2). Median mRS score at discharge was 2 in ischaemic stroke patients vs 4 in cases of haemorrhagic stroke.

At 3 months, patients were lost to follow-up or information could not be reliably collected in 2.2% of the cases. Concerning the remainder, 76.9% of the patients lived in their homes and 62.9% were independent for activities of daily living. The mortality rate was 10.9%. Fig. 2 presents patient outcomes at discharge and at 3 months.

DiscussionStroke registries are essential tools that increase our knowledge of the natural course of the disease and help us analyse the changes and trends in stroke management over the years. Furthermore, and from an administrative perspective, these tools provide a quality control system that every stroke team or unit requires.

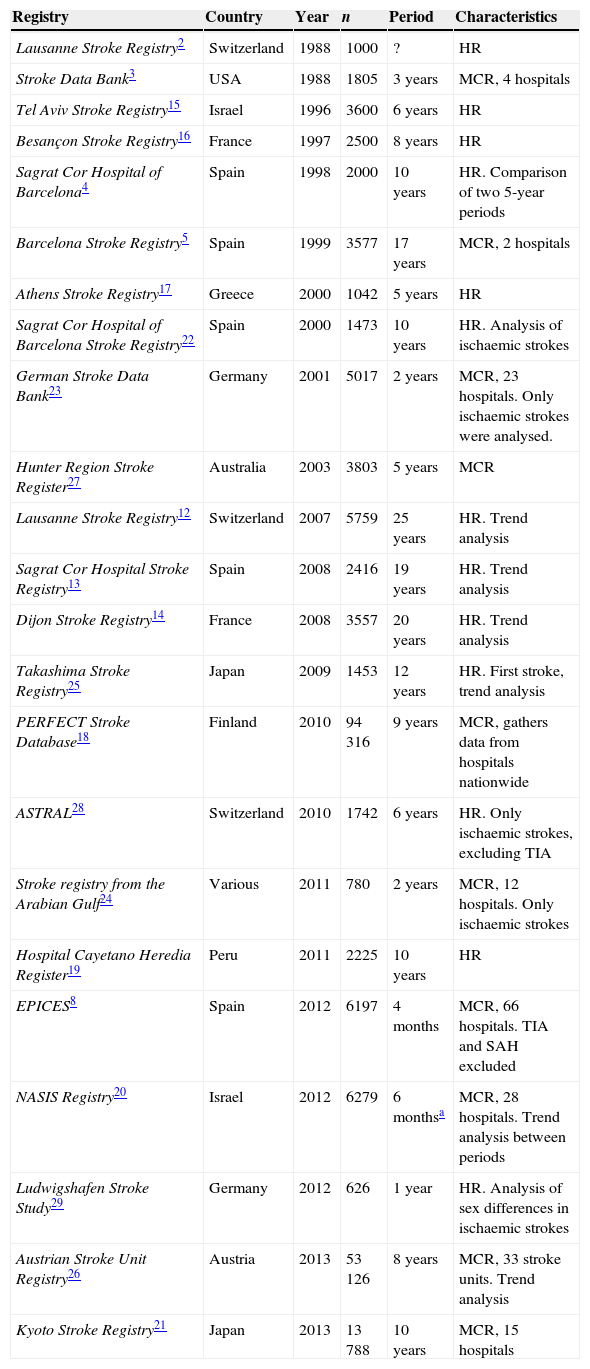

Table 3 summarises the stroke registries, each one with its own methodology, that have been published in the last 20 years. Multicentre registries let researchers study large numbers of patients in short periods of time. However, there may be a high level of heterogeneity between centres, which in turn can have an impact on many variables. Registries representing a single centre, as in our case, are homogeneous but require more time to amass a significant number of patients. In light of the above, and considering the constant advances in the diagnostic and therapeutic management of stroke, there may be many differences between the first and the more recent records. As a result, some of the first registries, which have now been active for more than 20 years, have published trend analyses illustrating changes in risk factor prevalence, stroke aetiology, or stroke outcomes, for example.12–14

List of reviewed stroke registries and main characteristics

| Registry | Country | Year | n | Period | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lausanne Stroke Registry2 | Switzerland | 1988 | 1000 | ? | HR |

| Stroke Data Bank3 | USA | 1988 | 1805 | 3 years | MCR, 4 hospitals |

| Tel Aviv Stroke Registry15 | Israel | 1996 | 3600 | 6 years | HR |

| Besançon Stroke Registry16 | France | 1997 | 2500 | 8 years | HR |

| Sagrat Cor Hospital of Barcelona4 | Spain | 1998 | 2000 | 10 years | HR. Comparison of two 5-year periods |

| Barcelona Stroke Registry5 | Spain | 1999 | 3577 | 17 years | MCR, 2 hospitals |

| Athens Stroke Registry17 | Greece | 2000 | 1042 | 5 years | HR |

| Sagrat Cor Hospital of Barcelona Stroke Registry22 | Spain | 2000 | 1473 | 10 years | HR. Analysis of ischaemic strokes |

| German Stroke Data Bank23 | Germany | 2001 | 5017 | 2 years | MCR, 23 hospitals. Only ischaemic strokes were analysed. |

| Hunter Region Stroke Register27 | Australia | 2003 | 3803 | 5 years | MCR |

| Lausanne Stroke Registry12 | Switzerland | 2007 | 5759 | 25 years | HR. Trend analysis |

| Sagrat Cor Hospital Stroke Registry13 | Spain | 2008 | 2416 | 19 years | HR. Trend analysis |

| Dijon Stroke Registry14 | France | 2008 | 3557 | 20 years | HR. Trend analysis |

| Takashima Stroke Registry25 | Japan | 2009 | 1453 | 12 years | HR. First stroke, trend analysis |

| PERFECT Stroke Database18 | Finland | 2010 | 94316 | 9 years | MCR, gathers data from hospitals nationwide |

| ASTRAL28 | Switzerland | 2010 | 1742 | 6 years | HR. Only ischaemic strokes, excluding TIA |

| Stroke registry from the Arabian Gulf24 | Various | 2011 | 780 | 2 years | MCR, 12 hospitals. Only ischaemic strokes |

| Hospital Cayetano Heredia Register19 | Peru | 2011 | 2225 | 10 years | HR |

| EPICES8 | Spain | 2012 | 6197 | 4 months | MCR, 66 hospitals. TIA and SAH excluded |

| NASIS Registry20 | Israel | 2012 | 6279 | 6 monthsa | MCR, 28 hospitals. Trend analysis between periods |

| Ludwigshafen Stroke Study29 | Germany | 2012 | 626 | 1 year | HR. Analysis of sex differences in ischaemic strokes |

| Austrian Stroke Unit Registry26 | Austria | 2013 | 53126 | 8 years | MCR, 33 stroke units. Trend analysis |

| Kyoto Stroke Registry21 | Japan | 2013 | 13788 | 10 years | MCR, 15 hospitals |

TIA: transient ischaemic stroke; SAH: subarachnoid haemorrhage; HR: hospital registry; MCR: multicentre registry.

An analysis of data from our series shows that haemorrhages occur in 10.9% (or in 11.9% if we exclude TIA, as some series do). In any case, this figure is similar to those from other series, which usually report rates between 8% and 25%.12–21 Registries from Spain estimate the frequency of haemorrhagic strokes at 12.4%-13.8%.8,13

The percentage of men in our series (54.1%) is similar to that reported by most series, in which this figure ranges between 47% and 63%.5,12,13,15–18,21–26 However, age in our series is older than in other series, which normally report ranges between 63 and 72 years.5,8,12,16–25,27 Only the Israeli registry published in 199615 and the Sagrat Cor Hospital of Barcelona stroke registry from 200813 reported similar or older mean ages. The latter registry also shows that the age of stroke patients has increased over the years, and similar tendencies have been observed in other countries, including France and Austria.14,26 Our series comprises patients who experienced a stroke in the last 10 years, and the most likely explanation for patients’ advanced age is that our hospital was not listed as referral centre for code stroke during that period. Because of this, younger patients would have been referred directly to the TRH. The rates for other vascular risk factors are similar to those reported in other series. The most prevalent risk factor in all cases, with no exceptions, is AHT, which is present in 47% to 78% of the patients.5,8,12–24,27

In our series, the most common aetiology for ischaemic stroke was cardioembolism, followed closely by atherothrombosis and small-vessel disease. These results are practically identical to those from the Spanish multicentre epidemiology study EPICES,8 with the latter showing a slightly higher percentage of atherothrombotic strokes. In any case, this percentage is comparable overall to figures reported by most published series.5,12–14,17,22,23,28,29 Exceptions include studies from the Arab states of the Persian Gulf,24 reporting a percentage of cardioembolic strokes of less than 14%. One noteworthy feature of our series is that it reports 14.7% of the strokes as cryptogenic after exclusion of those of undetermined origin due to coexistence of 2 causes and those not sufficiently studied. Many registries do not include this category, but studies that do include it report a percentage of cryptogenic strokes comparable to our own, with figures ranging between 14.8% and 17.5% in all of the cases.12,13,23 The exception is the Athens Stroke Registry and its surprisingly low percentage of 5.3%.17 Breakdown of strokes by arterial territory is reported in few series, but the most common finding is that the MCA is the most frequently affected, with figures ranging from 50.2% to 66.5%,5,12,13 slightly higher than the 46.6% in our series.

When we analyse haemorrhagic strokes, we observe that only a few registries record their aetiology and location. In the EPICES study,8 56.4% of the haemorrhagic strokes were due to hypertension. This percentage is similar to the 54.8% reported in our study. This figure varies greatly between different registries, ranging from 45% to 61.5%.5,12 Regarding location, the percentages of lobar, deep, and cerebellar or brain stem haemorrhage were 47.5%, 40.1%, and 12.4%, respectively. Results from the last period studied in the Lausanne Stroke Registry12 are similar (42.6, 46.5, and 10.8, respectively). In the Barcelona Stroke Registry,5 25% of haemorrhages were multiple, which makes interpreting results difficult. However, most haemorrhages were lobar.

Stroke severity by NIHSS score has rarely been reported in general series. Series limited to ischaemic strokes have reported 8.9 as the mean24 and 5 as the median.23 In the more recent Israeli registry that includes all stroke subtypes, researchers observed that 50% of the patients scored between 0 and 5 on the NIHSS, and that the percentage of less severe strokes is increasing over time.20 The median NIHSS score in our series is 3, indicating less severe strokes. The likely explanation for this tendency is that our centre was not a code stroke receiving hospital and that patients with more severe strokes were transferred immediately.

Mortality rate was low in our series (6.5%) compared to rates from other registries that range from 6.2% to 19.5%.13,15,16,19,20,28 Overall, most recent registries report lower mortality rates, which confirm the clear advances in treatment for this disease. The hospital registries that have compared their figures transversally also report lower mortality rates over the past few years.13,20

References to long-term outcome are much more scarce. Only 2 registries, both of which exclude all cases of haemorrhage, have reported the percentage of patients independent for activities of daily living (mRS=0-2) at 3 months; these figures range from 57.2% to 73.7%. This percentage in our series falls within that range (62.9%). One-month stroke mortality is considered to range between 17% and 30% (13%-23% for ischaemic strokes, and 2%-33% for haemorrhagic strokes).30 The PERFECT Stroke Database, including data from hospitals from all over Finland, reports a 3-month mortality rate of 20%.18 Our series reports a 3-month mortality rate of 10.9%, a figure considerably lower than those reported to date, and which is probably due to appropriate intra-hospital and extra-hospital treatment, prevention of complications, etc. This rate may also be affected by the lower severity of the strokes, although the Finnish registry does not report NIHSS scores.

In our opinion, there are no perfect registries and naturally our own registry has its limitations. Keeping a long-term hospital registry of an entity in constant evolution, such as stroke, means that the first and the last years are likely to show considerable variability, not only in management strategies but also in patient characteristics as we see in some registries.12–14,20 However, this type of registry does allow us to include a large number of patients from the same area. Furthermore, every hospital has its own specific traits that may generate biases. In the case of our centre, which was not listed as a code stroke receiving hospital, this idiosyncrasy has probably contributed to the lower stroke severity observed in our series. At the same time, it has prevented inclusion of such events as subarachnoid haemorrhage that must be treated in a tertiary care hospital.

In any case, stroke registries are useful and vital tools for furthering our knowledge of the course of these events and their diagnostic and therapeutic management. Furthermore, periodical reviews of registry data can play a role in quality control.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Palomeras Soler E, Fossas Felip P, Casado Ruiz V, Cano Orgaz A, Sanz Cartagena P, Muriana Batiste D. Registro de Ictus del Hospital de Mataró: 10 años de registro en un hospital comarcal. Neurología. 2015;30:283–289.

Presented at the 64th Annual Meeting of the Spanish Society of Neurology.