The number of people who seek medical care due to cognitive symptoms has increased significantly in recent years, mainly due to the increase in the population's life expectancy. Cognitive assessments are essential in the differential diagnosis of dementia,1 since they contribute to treatment decision-making, which will affect the quality of life of patients and their families.

Quick cognitive screening tests are especially useful in our setting due to long waiting lists and limited resources that do not allow specialists to administer more thorough neuropsychological tests.

Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination III (ACE-III)2 has recently been validated in Spanish.3 Both the current and previous versions of this test are widely used in memory units and dementia research centres around the world.4 The ACE-III is known for its ability to detect dementia and differentiate between dementia subtypes.5 However, its use is not as widespread as one might like since it takes 15-20minutes to administer.

Hsieh et al.6 have developed and validated the Mini-Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination (M-ACE), a brief version of the ACE-III. These authors reduced the original version using Mokken scaling7 and administered the new version to patients with Alzheimer-type and frontotemporal dementia and to healthy controls. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was used as the gold standard.8

The M-ACE includes 5 items (orientation to time, semantic fluency, clock face drawing, immediate recall, and delayed recall) with a maximum score of 30. Maximum administration time is approximately 5minutes. In the original validation study, scores≤25/30 were identified as the cut-off point for dementia with both high sensitivity (85%) and specificity (87%). The M-ACE was found to be more sensitive than the MMSE and showed a less pronounced ceiling effect.

We have studied the psychometric properties of this new version of the ACE-III in our population using the same methodology applied by its authors and the complete sample recently gathered for the ACE-III validation study.

We selected items from the original questionnaire that are included in the M-ACE and created a new score. Of the 175 subjects comprising the sample, 92 were cognitively healthy controls (age: 77.0±6.4 years; education: 8.4±5.8 years) and 83 were patients (age: 78.4±6.8 years; education: 7.4±4.7 years) diagnosed with different types of dementia in mild stages: Alzheimer disease (46 patients, 55.4%), vascular dementia (4, 4.8%), mixed dementia (9, 10.8%), dementia associated with Parkinson's disease (11, 13.3%), Lewy body dementia (6, 7.2%); frontotemporal dementia (5, 6%), alcoholic dementia (1, 1.2%), and atypical parkinsonism with dementia (1, 1.2%). All participants were at least 65 and they were recruited from neurology departments at Hospital Clínico San Carlos in Madrid and Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau in Barcelona.

Our sample was significantly older and had a lower educational level than the sample in the study by Hsieh et al.6 In the reliability analysis, the scale showed high internal consistency (Cronbach α=0.828).

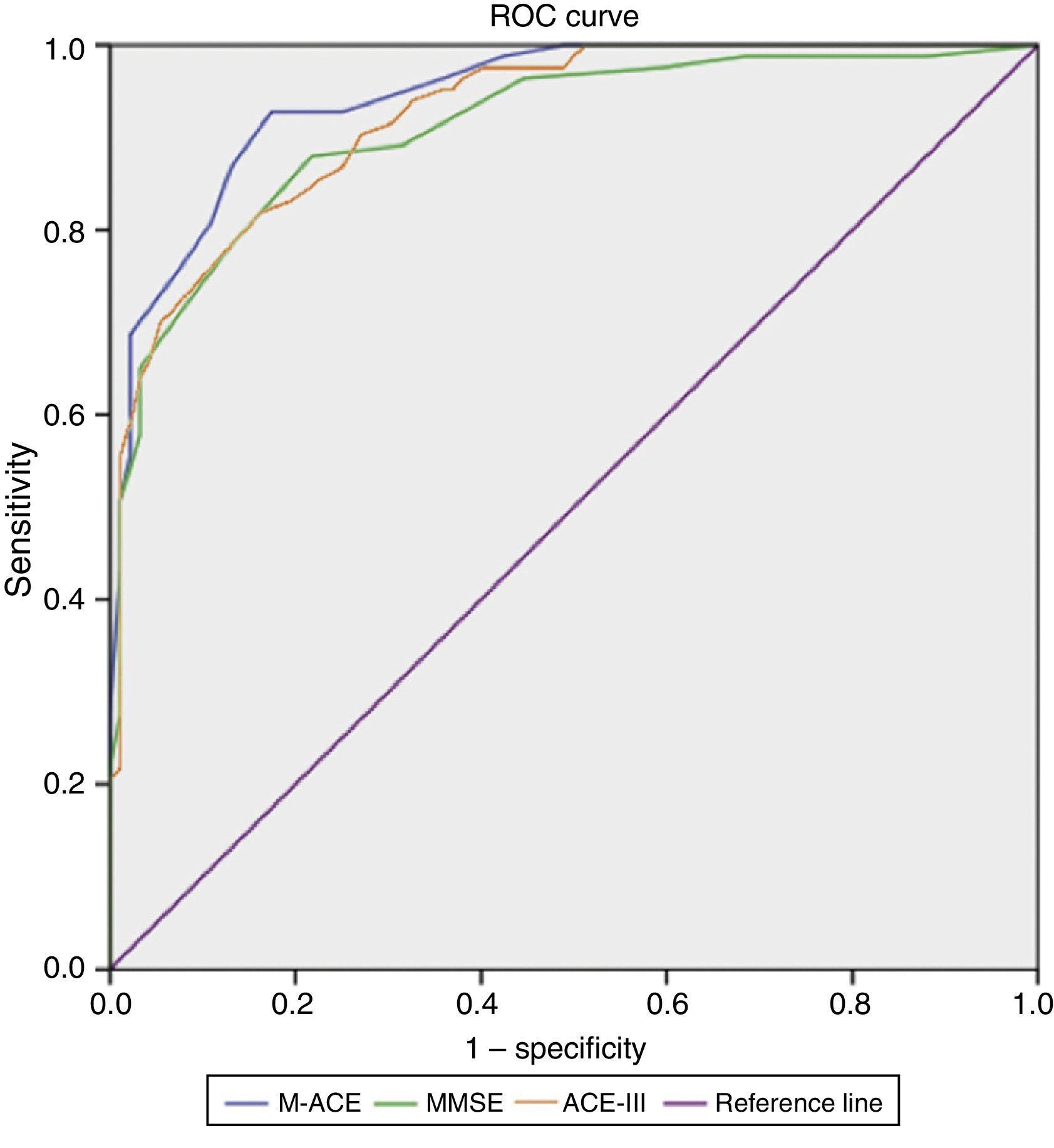

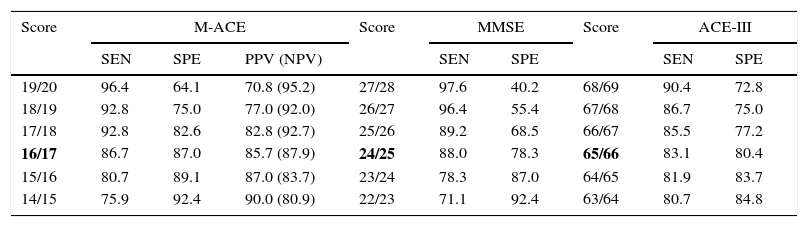

Results on the M-ACE were compared to those on the ACE-III and MMSE; clinical diagnosis of dementia was used as the factor for determining cut-off points (Fig. 1). With an area under the curve (AUC)=0.94, M-ACE scores≤16/30 were identified as the cut-off point for dementia with high levels of sensitivity (86.7%) and specificity (87.0%). This means that the M-ACE achieves better discrimination indices than the MMSE (AUC=0.91; score≤24/30; sensitivity=88.0; specificity=78.3) and the ACE-III (AUC=0.92; score≤65/100; sensitivity=83.1; specificity=80.4) (Table 1).

Cut-off points for a diagnosis of mild dementia.

| Score | M-ACE | Score | MMSE | Score | ACE-III | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEN | SPE | PPV (NPV) | SEN | SPE | SEN | SPE | |||

| 19/20 | 96.4 | 64.1 | 70.8 (95.2) | 27/28 | 97.6 | 40.2 | 68/69 | 90.4 | 72.8 |

| 18/19 | 92.8 | 75.0 | 77.0 (92.0) | 26/27 | 96.4 | 55.4 | 67/68 | 86.7 | 75.0 |

| 17/18 | 92.8 | 82.6 | 82.8 (92.7) | 25/26 | 89.2 | 68.5 | 66/67 | 85.5 | 77.2 |

| 16/17 | 86.7 | 87.0 | 85.7 (87.9) | 24/25 | 88.0 | 78.3 | 65/66 | 83.1 | 80.4 |

| 15/16 | 80.7 | 89.1 | 87.0 (83.7) | 23/24 | 78.3 | 87.0 | 64/65 | 81.9 | 83.7 |

| 14/15 | 75.9 | 92.4 | 90.0 (80.9) | 22/23 | 71.1 | 92.4 | 63/64 | 80.7 | 84.8 |

The cut-off point found to be optimal is shown in bold.

NPV: negative predictive value; PPV: positive predictive value; SEN: sensitivity; SPE: specificity.

The M-ACE demonstrated a high diagnostic ability, with values above 85% for discrimination between healthy controls and subjects with mild dementia. The optimal cut-off point was 16.5, although a slightly higher point (17.5) would probably be recommendable to increase sensitivity, since this is the main purpose of a screening test. This cut-off point is below 25, the proposed threshold in the study of the English-language version. However, the original study only included patients with Alzheimer-type and frontotemporal dementia, who were also younger and more educated.

In conclusion, our study is the first to apply the M-ACE to a Spanish-speaking population, and it demonstrates the usefulness of this scale as a cognitive screening test. The short time required to administer the M-ACE suggests that this tool may be useful in centres with a greater care load or in less specialised centres. In addition, the higher sensitivity and specificity of the M-ACE compared to the ACE-III supports using the former even when the original long form is also administered. The M-ACE would therefore serve 2 purposes in neuropsychological assessment: it is a screening tool, especially when combined with the ACE-III, and also a short neuropsychological test since it includes the domains assessed by the ACE-III (attention, language, memory, verbal fluency, and visuospatial fluency).

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Matias-Guiu J, Fernandez-Bobadilla R. Validación de la versión española del Mini-Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination para el cribado de demencias. Neurología. 2016;31:646–648.