I would like to thank the Spanish Society of Neurology for their opportune and long-awaited article ‘Clinical management guidelines for subarachnoid haemorrhage. Diagnosis and treatment’.1 With their appearance online in 2012, these guidelines filled a void in our medical literature, following the publication of the European guidelines,2 the guidelines of the Spanish Society of Neurosurgery,3 and the American Heart Association's reviewed guidelines.4 I would also like to take advantage of this opportunity to add some comments.

Stroke units are unquestionably necessary; however, not all vascular neurologists are equally able to admit patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (aSAH) to their stroke units. In reality, there are marked differences between hospitals. Paradoxically, cerebral ischaemia, an entity with similar morbidity and mortality, is treated by specialists and in a different unit. In a study published in 2005, Alberts et al.5 recommended using trauma centre principles to treat patients with neurovascular diseases. In a previous article, we called attention to the lack of effectiveness of current treatment approaches in neurovascular emergencies.6 Regarding endovascular treatment, Arias7 stated that ‘radiologists, neurologists, and neurosurgeons may soon work together in this field’.

Time to treatment and treatment type may have legal consequences, and these guidelines do not specify the time frame for early treatment. Due to this lack of precision, some clinicians define early treatment as that delivered within 24hours of aneurysm rupture whereas others use the 72-hour time mark. Treatment within 3 days of subarachnoid haemorrhage has traditionally been regarded as early treatment.2,3 According to the literature, maximum incidence of rebleeding takes place during the first few hours; early treatment should be provided to avoid this severe complication, which worsens clinical outcomes. However, any treatment approach to aneurysm repair not fulfilling certain conditions is worse than delaying the treatment of aSAH.

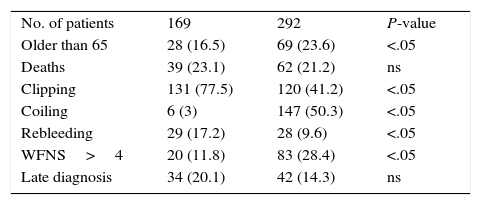

According to Vivancos et al.,1 mortality from this event has decreased considerably in the past years. We analysed 2 series of patients with aSAH separated by a period of 10 years (Table 1). During that period, endovascular treatment began to be used in our hospital. From a register of patients with neurovascular diseases, we selected those with aSAH belonging to one of 2 periods: 1993-1997, when endovascular treatment was not available at our hospital; and 2008-2012, after full implementation (endovascular treatment was first introduced in 1998). We gathered the following data: age (>65 years), clipping, endovascular treatment, rebleeding, WFNS scale scores (>4), late diagnosis, and in-hospital mortality. Statistical analysis was performed using OpenEpi version 3.01. The total number of patients was considerably higher in the second period for unexplained reasons. No statistically significant differences were found between the 2 periods in terms of mortality and late diagnosis. The percentage of patients undergoing surgery was higher in 1993-1997; on the other hand, endovascular treatment increased significantly between 2008 and 2012. The incidence of rebleeding was considerably lower in the second period. The percentage of patients with poor neurological outcomes was significantly higher in the second period. According to our data, mortality associated with aSAH seemed stable, although we do not know whether this was due to the higher number of patients who survived but were incapacitated. The second period saw a rise in the number of older patients and those having a poorer neurological state. The decreased incidence of rebleeding in the second period was due to early treatment, which was rarely administered during the first period. Late diagnosis of aSAH is still a major concern in our setting. The increased use of endovascular techniques has not had a significant impact on outcomes since the most crucial factor remains SAH severity.8

Comparison of 2 series (1993-1997 and 2008-2012) of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage.

| No. of patients | 169 | 292 | P-value |

| Older than 65 | 28 (16.5) | 69 (23.6) | <.05 |

| Deaths | 39 (23.1) | 62 (21.2) | ns |

| Clipping | 131 (77.5) | 120 (41.2) | <.05 |

| Coiling | 6 (3) | 147 (50.3) | <.05 |

| Rebleeding | 29 (17.2) | 28 (9.6) | <.05 |

| WFNS>4 | 20 (11.8) | 83 (28.4) | <.05 |

| Late diagnosis | 34 (20.1) | 42 (14.3) | ns |

WFNS, World Federation of Neurological Surgeons scale.

Lastly, for those interested in delayed ischaemic neurological deficits (vasospasm), these guidelines offer a thorough review of drugs for vasospasm which have been proved ineffective.

Please cite this article as: Vilalta J. Guía de actuación clínica en la hemorragia subaracnoidea. Sistemática diagnóstica y tratamiento. Neurología. 2016;31:645–646.