Stiff person syndrome (SPS) is a rare disorder characterised by muscle rigidity and painful intermittent spasms. It has been suggested to have an autoimmune basis since it features antibodies which act on the GABAergic system and it is associated with other autoimmune disorders.1–3 It affects trunk and limb muscles especially. There are several forms of SPS, including generalised and focal forms and other more rare variants with brain and spinal cord involvement.

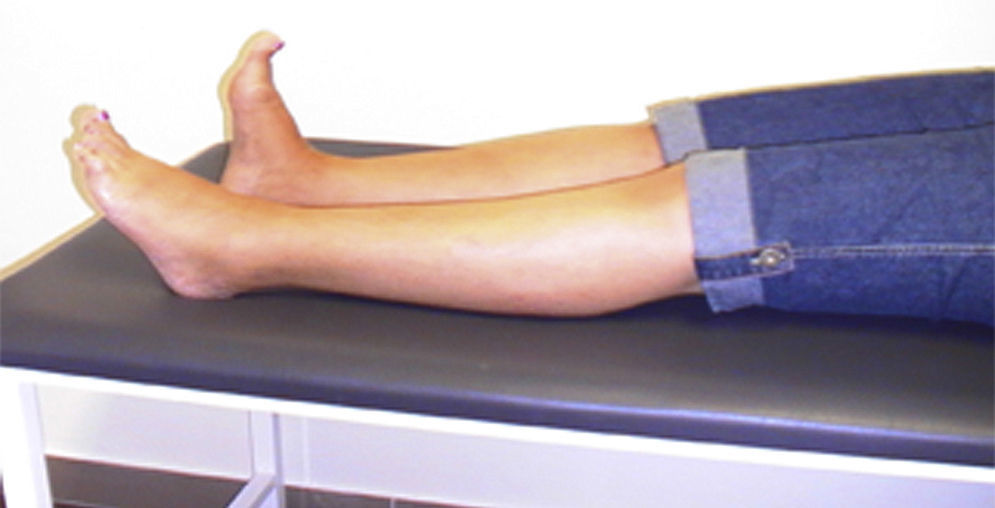

We present the case of a woman who at the age of 46 began to experience painful spasms in her left foot and abnormal posturing with extension of its first digit. Symptoms progressed over 5 years (Fig. 1) until our patient's left leg became stiff, causing her to fall frequently.

The results from brain and spinal cord MRI scans were normal. A SPECT study with ioflupane (123I) also yielded normal results. We conducted laboratory analyses, including a complete blood count, copper metabolism test, basic immunology test, and tests for thyroid function, tumour markers, and antineuronal antibodies. Results were normal except for the following findings: anti-GAD antibodies (glutamate decarboxylase) >250U/L, measured at 2 different times; a moderate level of ANA (1:160, reticular dotted pattern); and presence of islet cell antibodies (ICA). The patient tested negative for anti-amphiphysin antibodies. Screening for occult neoplasm also yielded negative results.

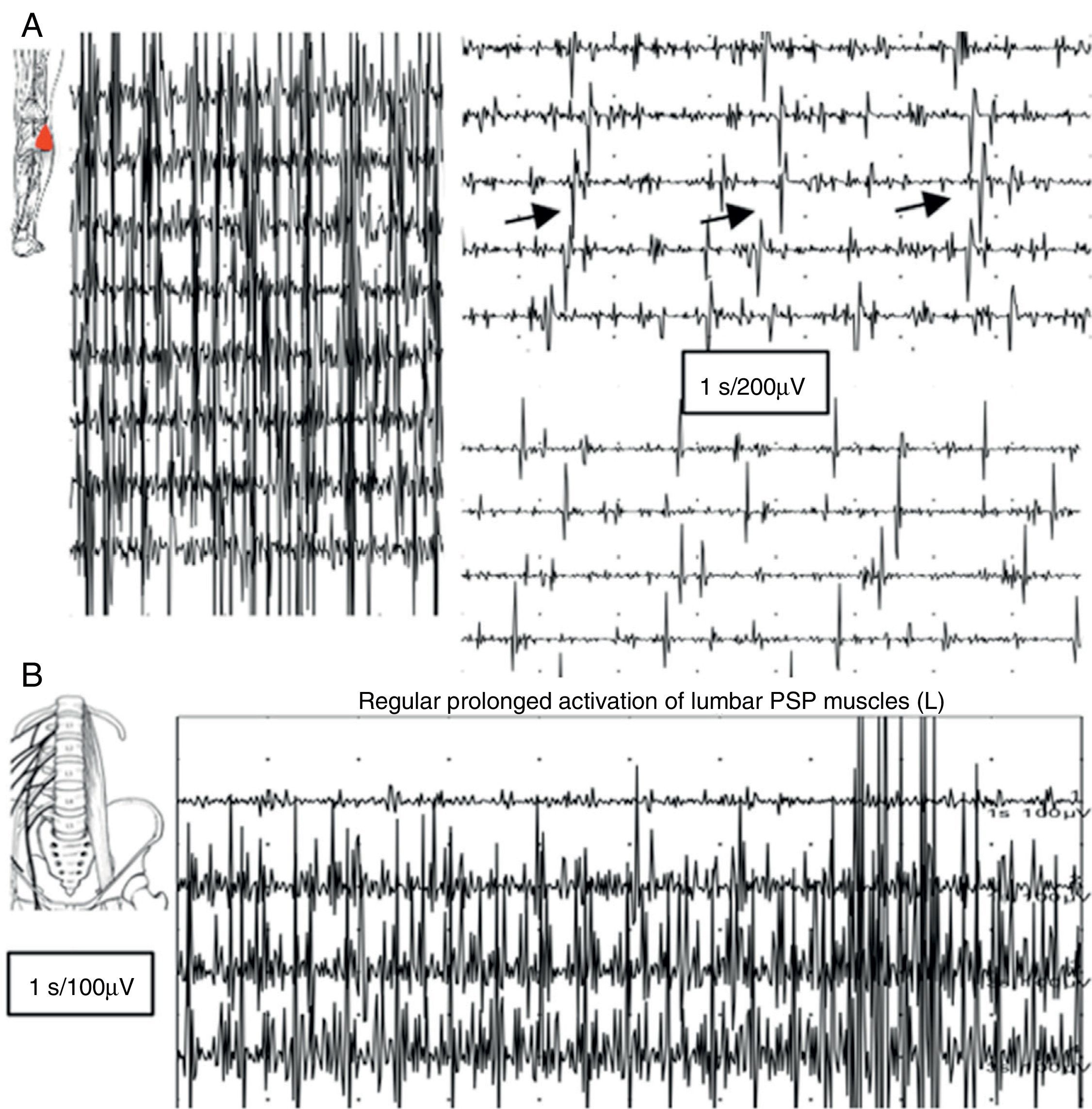

An EMG study revealed continuous muscle fibre activity in the left lower limb, predominantly affecting flexor and extensor muscles, and the lumbar paraspinal muscles. Motor units showed normal morphology and did not disappear with distraction movements or antagonist muscle activation (Fig. 2).

(A) EMG reading of the lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscle: voluntary contraction is followed by lack of muscle relaxation alternating with short, apparently semi-rhythmic contractions at a frequency of 5Hz. (B) Muscle activity at rest was recorded using a concentric needle electrode inserted in the lumbar paraspinal muscles: lack of relaxation of muscle fibres with continuous, normal MUP activity.

Based on these results, our patient was diagnosed with stiff leg syndrome, a partial form of SPS. Since then our patient has been treated with diazepam, baclofen, and gabapentin. Treatment has improved spasms and pain considerably, although she continues to experience falls as well as freezing of gait in stressful situations. After 9 years, her prognosis is poor, with increased limb stiffness and lumbar hyperlordosis, difficulty walking (freezing of gait and difficulty in initiating gait), and frequent falls, as well as anxiety, phobia, and avoidance coping.

SPS is a hyperexcitability syndrome affecting spinal motor neurons. It is characterised by progressive muscle stiffness that is predominantly axial, superimposed muscle spasms, and hypersensitivity to external stimuli.3,4 Incomplete variants of SPS include stiff limb syndrome (as in our case), which may evolve into a complete form; SPS associated with myoclonus; SPS associated with epilepsy and dystonia; SPS with neuro-ophthalmic manifestations; progressive encephalomyelitis with rigidity; and cerebellar variant of SPS.

Episodic spasms are triggered by such factors as emotional stress, sudden external stimuli, cold, intercurrent infections, or rapid movements. Patients with SPS typically present psychiatric symptoms, including fear of leaving the house and reactive depression; these traits may result in an incorrect or delayed diagnosis. It has been suggested that stressful psychological or psychosocial factors may trigger a hidden autoimmune process.5

Typical EMG findings include continuous motor unit activity while resting despite attempts to relax, normal morphology, no signs of acute denervation or spontaneous activity, and normal recruitment pattern.3,6,7 Agonist and antagonist muscles contract simultaneously, causing the so-called induced reflex spasms.

From a pathophysiological viewpoint, SPS is associated with presence of anti-GAD antibodies which act on the GABAergic system by inhibiting its function, thus leading to abnormal muscle hyperexcitability. However, not all SPS patients described in the literature are positive for this antibody (60%-90% of the cases are positive),2,3 and other disorders have been associated with presence of anti-GAD antibodies.8

Currently available treatments include drugs intended to increase GABA activity (benzodiazepines, baclofen) and immunomodulatory and/or immunosuppressant treatments (prednisone, IV immunoglobulins, plasmapheresis, rituximab, mycophenolate, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, and methotrexate).9 Antiepileptic drugs (valproate, vigabatrin, gabapentin, levetiracetam, tiagabine) have also been used with mixed results. Onabotulinum toxin A has also been tested, although it has yet to be proved effective.9 Experts also recommend early treatment of psychiatric symptoms associated with the disease.5

SPS should be considered in the differential diagnosis of focal dystonia, especially in cases of lower limb involvement10 since associated disability is severe but may improve with correct diagnosis and treatment.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Payo Froiz I, Descals Moll C, Montalà Reig JC, Usón Martín M, Espino Ibáñez A. Forma focal y de larga evolución del síndrome de la persona rígida. Neurología. 2016;31:643–644.