Intracranial hypotension syndrome (IHS) is due to imbalances in the production and absorption of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). It is mainly caused by CSF leakage owing to structural weakness of the meninges alone or in combination with local trauma to the spinal dura mater. Symptoms appear when pressure drops below 65mmH2O.1

We present the case of a patient with CSF hypotension who experienced a complex partial seizure with secondary generalisation which led to a diagnosis of cortical vein thrombosis.

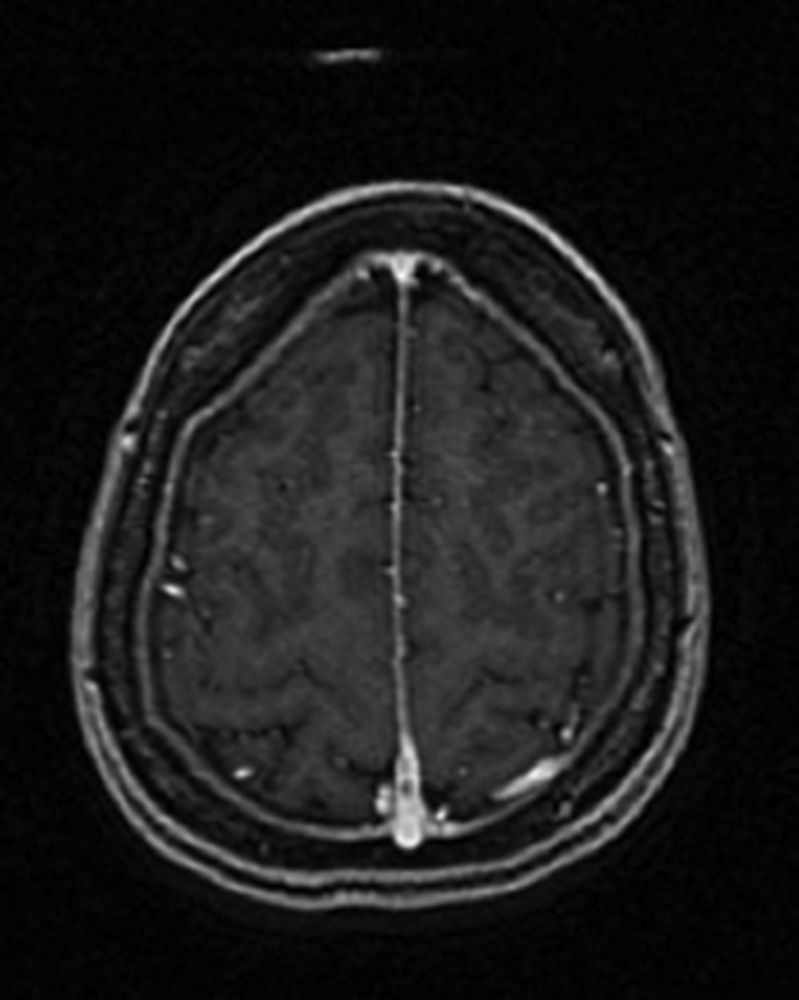

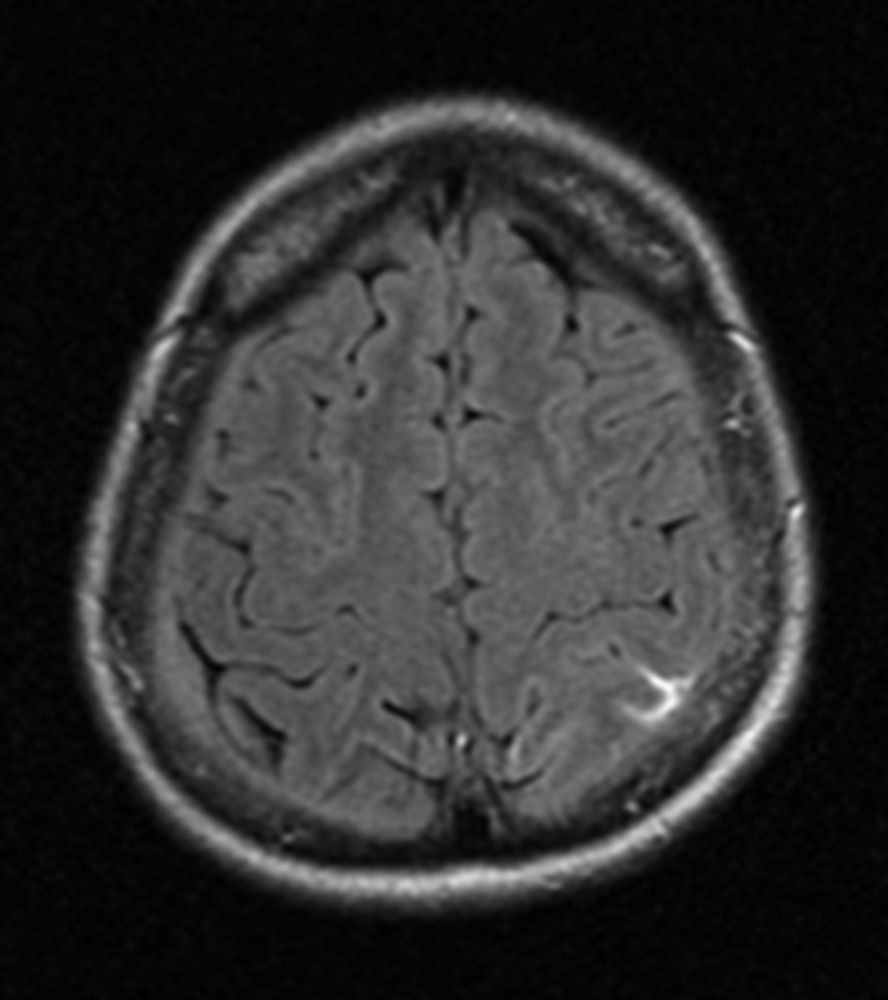

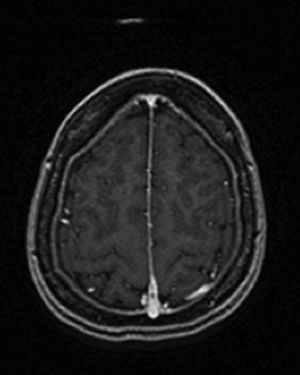

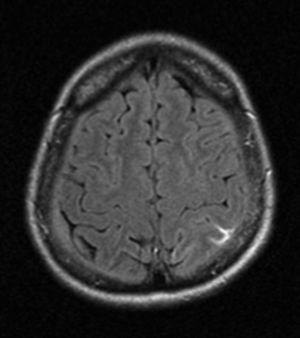

Our patient was a 40-year-old Ukrainian woman with a history of episodic migraine with aura beginning in adolescence. She had no other personal or family history of interest, epilepsy risk factors, oral contraceptive use, or prothrombotic risk factors. The patient visited our hospital due to constant headache which was more intense than her usual migraine episodes, and had different characteristics. She described the headache as oppressive and holocranial, and reported nausea and vomiting. Pain worsened when standing, sitting, and during Valsalva manoeuvers, and lessened in the decubitus position. Over time, pain became continuous and interfered with our patient's nightly sleep. A MRI scan revealed diffuse dura mater enhancement and increased size of the pituitary gland and the proximal cervical and intracranial venous plexi; these findings were all compatible with CSF hypotension. Two weeks later our patient experienced a self-limiting episode lasting 10minutes and featuring paraesthesias of the right hand which progressed to the right side of her upper lip. A few hours later, she reported disorientation, paraesthesia, and loss of strength which progressed proximally from her right hand to her right forearm. On arriving at the emergency department, she displayed language impairment, right limb paresis, and psychomotor agitation. At the emergency department our patient experienced a self-limiting generalised tonic-clonic seizure lasting 2minutes with no recurrences. The results of the neurological examination conducted after the post-critical phase were normal, and a new cranial CT scan revealed no new changes since the previous one. An EEG revealed slow activity in the left temporoparietal region. An additional MRI scan showed T1 hyperintensity and T2 hypointensity of a left parietal superior cortical vein at the level of the parasagittal convexity, compatible with cortical venous thrombosis. In addition, adjacent sulci were hyperintense on FLAIR, which suggested subarachnoid haemorrhage. Likewise, the signs of CSF hypotension seen in the previous MRI scan remained visible (Figs. 1 and 2). Symptoms improved significantly with conservative treatment (hydration, caffeine, intravenous corticosteroids, and antiepileptics). We decided not to administer anticoagulants due to the risk of bleeding associated with CSF hypotension.

Although it is not infrequent in clinical practice, headache secondary to CSF hypotension is still underdiagnosed.2

Orthostatic headache is the typical and most frequent manifestation of CSF hypotension, but we should never forget other less frequent, more severe symptoms, such as cerebral venous thrombosis. Cerebral venous thrombosis should be suspected in patients with CSF hypotension presenting altered headache patterns or focal neurological signs. In these cases, the necessary studies should be conducted to rule out this entity or detect CSF leaks if the diagnosis is confirmed.3–6 Further studies are necessary to determine the best treatment for cerebral venous thrombosis in patients with CSF hypotension and increased risk of subdural haematoma.6–9 In our case, we decided not to administer anticoagulants since our patient was clinically stable.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Pérez Pérez A, Calvo Porqueras B, Porta Etessam J, Jorquera Moya M. Hipopresión de líquido cefalorraquídeo como causa de trombosis de una vena cortical. Neurología. 2016;31:648–649.