Central nervous system germ cell tumours are neoplastic proliferations of germ cells; their incidence is very low in Western countries, representing fewer than 0.5% of all primary intracranial tumours. In Asian countries, however, germ cell tumours are more frequent.1 They may be classified into different histological subtypes, with germinomas being the most common, accounting for up to 69% of cases.2 These tumours are usually diagnosed in childhood, with 90% of patients being younger than 25 years.3 The clinical manifestations of germ cell tumours vary according to their location. These tumours exhibit variable radiological characteristics, frequently presenting as oval-shaped or lobulated masses located in the pineal gland (38%-57%), suprasellar region (34%-49%), or in both locations (5%-10%). Only 3%-5% of cases involve such other regions as the ventricles.4,5 Definitive diagnosis is based on histopathological findings, and treatment consists of radiotherapy alone or combined with chemotherapy, achieving remission in up to 90% of cases.6

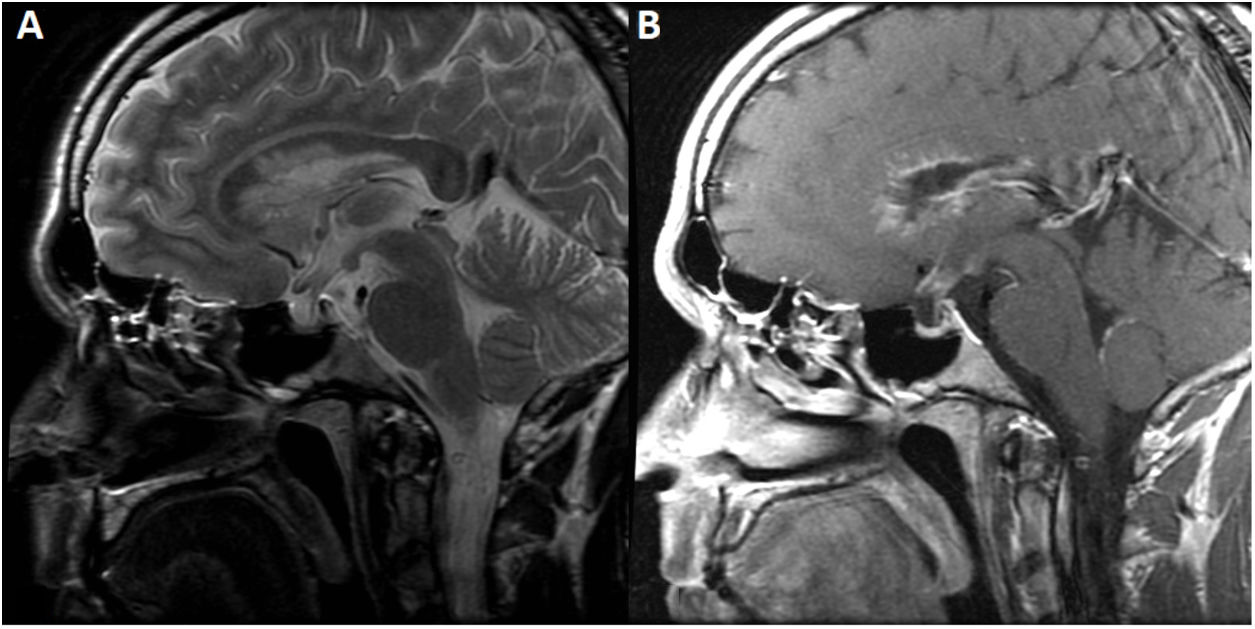

We present the case of a 31-year-old white man, born in Spain, a smoker, with no relevant medical history, who consulted due to a 3-month history of asthenia, nausea, polyuria with polydipsia, reduced libido, loss of appetite, and weight loss of 6 kg. The neurological examination revealed horizontal gaze–evoked nystagmus. A blood analysis revealed low cortisol levels; strikingly, ACTH levels were within the normal range. Testosterone, LH, FSH, and IGF-1 levels were also low, with elevated prolactin levels. The patient was diagnosed with panhypopituitarism, and hormone replacement therapy was started. A brain MRI scan revealed a small pituitary gland, lack of the normal hyperintensity observed in the posterior pituitary on T1-weighted sequences, and supra- and infratentorial ependymal enhancement involving the corpus callosum and the pituitary stalk in post-contrast sequences (Fig. 1).

Brain MRI scan. A) Sagittal T2-weighted fast spin-echo sequence showing a smaller-than-normal pituitary gland for the patient’s age. The image also shows cotton wool–like periventricular signal hyperintensity in the genu and body of the corpus callosum. B) Sagittal T1-weighted fast spin-echo post-contrast sequence showing pseudonodular contrast uptake in the ependyma of the frontal horns, extending to the corpus callosum, coinciding with the signal alteration observed on T2-weighted sequences, and smooth contrast uptake in the fourth ventricle and upper part of the pituitary stalk. No lesion or pathological contrast uptake was observed in the pineal gland.

A CSF analysis revealed mildly elevated protein levels (82 mg/dL) and lymphocytic pleocytosis (25 cells/mm3), with no monoclonal bands. We expanded the study with an autoantibody panel; blood ACE and tumour marker tests; a 24-h urine calcium test; a spinal cord MRI scan; a chest CT scan; CSF cultures for bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungi; and PCR and serology tests for neurotropic pathogens in the CSF and blood. All tests yielded negative results. A whole-body PET scan requested due to suspicion of systemic disease only detected fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the areas of ependymal enhancement; this suggests a benign inflammatory process or low-grade malignancy.

Given the lack of severe symptoms after onset of hormone replacement therapy and the lack of evidence of disease in other, more accessible sites for biopsy sample collection, the patient was discharged and closely followed up on an outpatient basis.

The patient was admitted to hospital 6 months later due to cognitive impairment and behavioural alterations. The neurological examination revealed neuropsychiatric alterations and bilateral internuclear ophthalmoplegia. An MRI scan revealed an increase in the size and extension of the areas displaying contrast uptake. Another CSF analysis revealed greater severity of lymphocytic pleocytosis (40 cells/mm3) and higher protein levels (98 mg/dL). A microbiological study of the CSF yielded positive PCR results for Epstein-Barr virus. A brain biopsy only revealed polyclonal reactive lymphocytosis. Suspicion of persistent Epstein-Barr virus encephalitis led us to start treatment with ganciclovir and corticosteroids, which improved the patient’s symptoms and decreased CSF pleocytosis.

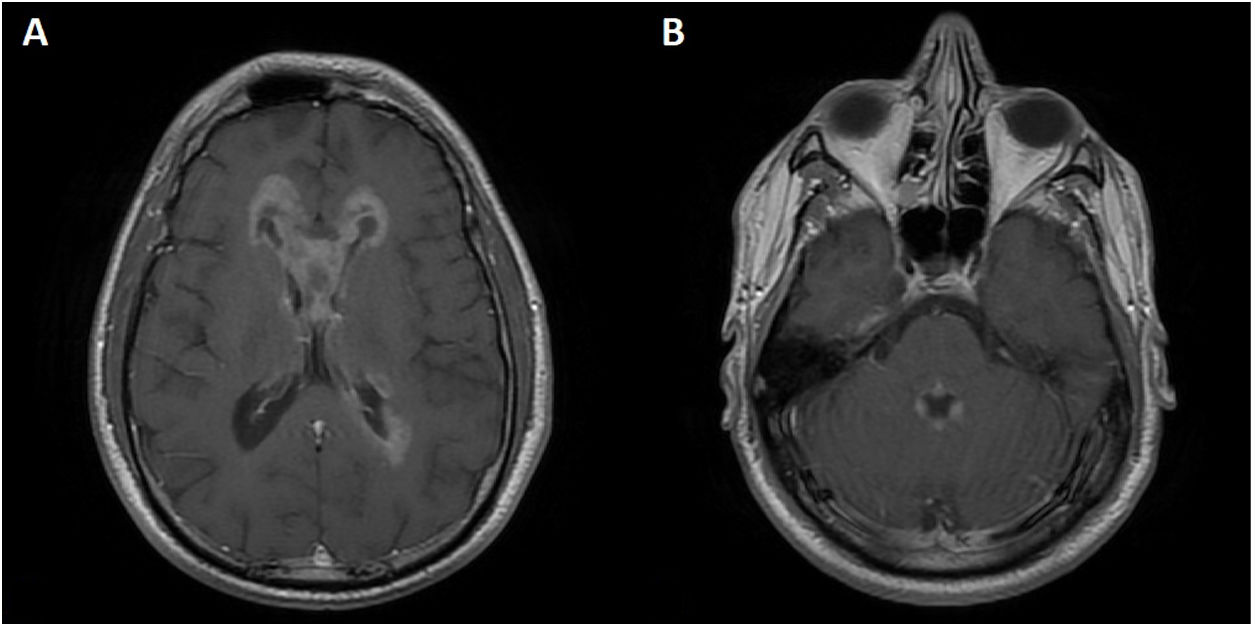

Several months later, the patient presented progressive worsening, with dysarthria and right hemianopsia, coinciding with prednisone tapering. Another brain MRI scan revealed an increase in the extension of the areas displaying contrast uptake (Fig. 2). A new brain biopsy identified pure germinoma. The patient was referred to the oncology department for radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

Very few cases have been reported of CNS germinomas involving the supra- and infratentorial ependyma and midline structures, with no clear lesions in the suprasellar region and pineal gland.4 In the case presented here, the 2 most probable diagnostic hypotheses were infection and lymphoproliferative neoplasia; germinoma was considered to be highly unlikely due to the neuroimaging findings and the patient’s age and geographical region of origin. Although biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosing germinoma, its sensitivity ranges from 87% to 94.8%7; furthermore, reactive inflammation may mask the tumour.8

CNS germinoma is a potentially fatal but treatable tumour. Though rare, it should be suspected in patients presenting diffuse, selective periventricular and ependymal involvement.

Please cite this article as: Sanesteban Beceiro E, Mayo Rodríguez P, Jorquera Moya M, Ginestal López RC. Germinoma primario del sistema nervioso central como causa infrecuente de afectación ependimaria difusa en el adulto. Neurología. 2022;37:308–310.