The association between migraine and vestibular symptoms is well known, and the possibility of central or peripheral nervous involvement has been discussed in the literature.1

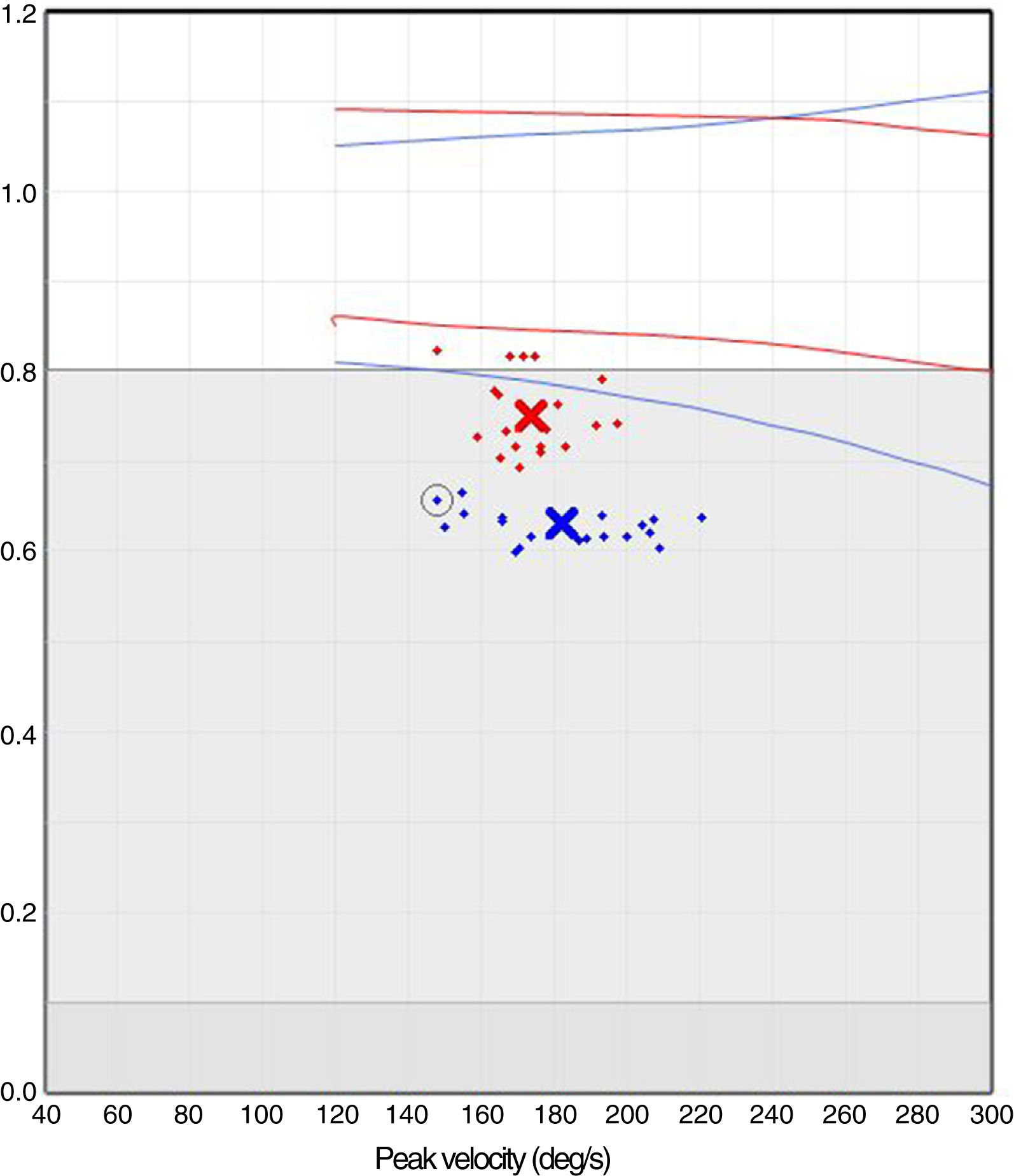

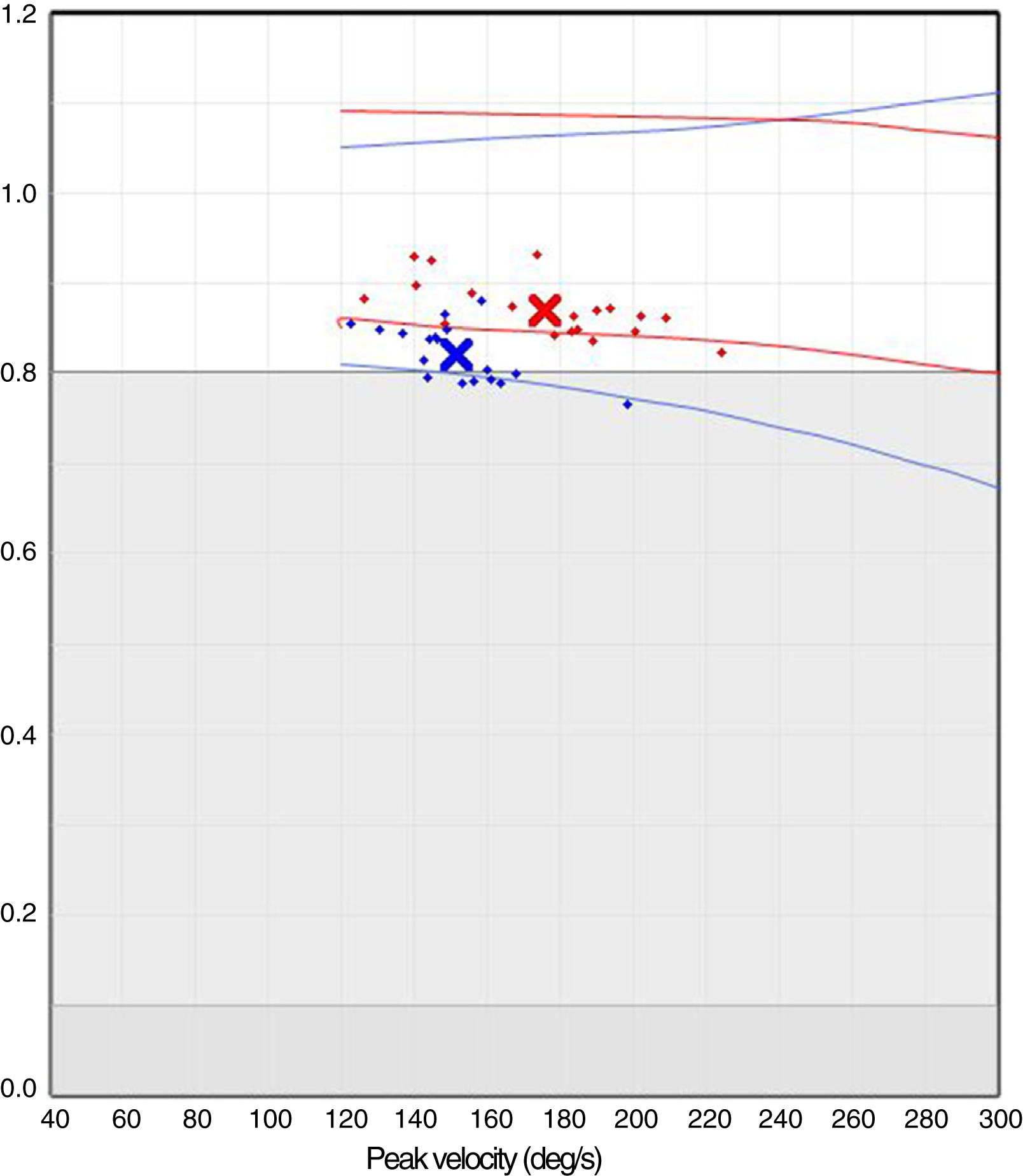

We present the case of a 34-year-old woman who attended our department due to a 3-week history of pronounced instability of rapidly progressive onset (3hours). The neurological examination revealed normal results, and the neuro-otological examination, including the head impulse test and the Halmagyi head thrust test, showed no alterations. She provided us with a brain MRI scan obtained at a different centre, which showed no remarkable alterations. The patient was diagnosed with psychogenic dizziness and started treatment with sertraline at 25mg; she was assessed the following week with a video head impulse test (v-HIT). The patient presented no clinical improvement, and the v-HIT showed bilateral vestibular hypofunction (Fig. 1); we prescribed topiramate (50mg by night) in addition to the sertraline. At one month, the patient was practically asymptomatic, and a second v-HIT returned normal results (Fig. 2).

The association between vestibular symptoms and migraine has long been known, and research has been dedicated to the subject in recent years. Patients often manifest migraine-associated recurrent vertigo (MARV),2 a highly incapacitating condition that presents with illusions of motion, and may progress for hours or days. The most plausible current hypothesis is that this process involves central and peripheral structures. Furthermore, patients manifest kinesiophobia, or fear of movement, during attacks; kinesiophobia may be associated with vestibular sensitisation. Finally, as a differentiated entity, an increase has been observed in benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in younger patients.3 The presence or absence of vertigo or instability depends on the rapidity of onset of the vestibular syndrome, asymmetrical involvement, degree of involvement, and progression time.4 Our patient presents clear symptoms of instability with kinesiophobia but no illusion of motion, as involvement was bilateral. Furthermore, the positive v-HIT findings suggest peripheral involvement; therefore, this entity is characterised by symptoms of central origin with secondary peripheral involvement, as is the case with migraine.

MARV, instability due to bilateral vestibular hypofunction, and kinesiophobia probably share a common pathophysiological mechanism. All 3 conditions are caused by central and peripheral nervous system involvement manifesting as vestibular hypofunction. Unilateral involvement may be the cause of MARV, whereas mild bilateral involvement may have caused kinesiophobia, and moderate bilateral involvement would cause instability. Vestibular afferences are known to project to temporal cortical regions.5 Trigeminal stimulation is reported to involve a similar phenomenon to that observed with migraine, with protein extravasation in the inner ear.6,7 These phenomena may explain the clinical symptoms observed.

Another interesting aspect is the need to use specific techniques such as v-HIT to establish an adequate diagnosis. The patient, assessed in a specialised neurology and otology unit, was initially diagnosed with dizziness of neurophysiological origin; the specific examination enabled us to establish a correct diagnosis and indicate appropriate treatment.

Migraine and associated vestibular entities share some pathophysiological features. Peripheral dysfunction secondary to central nervous system involvement is a possible cause in both conditions. Knowledge and diagnosis of the condition enable us to adapt the treatment. Proper neurological and otological assessment can be crucial in these patients.

Please cite this article as: Porta Etessam J, González N, García-Azorín D, Silva L. Hipofunción vestibular bilateral intercrítica en una paciente con migraña. Hacia la hipótesis integradora. Neurología. 2020;35:448–449.