Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) is a neurological disorder consisting in cerebrovascular dysregulation with acute neurological symptoms, including headache. However, there is a paucity of data that point to headache as a sequela of PRES. We aimed to explore its prevalence, characteristics, and impact.

MethodsWe retrospectively included all consecutive patients with PRES attended at our institution from April 2018 to January 2022. We collected demographic and clinico-radiological data from the acute phase. During a mean follow-up time of 16 (14) months, we assessed the presence of headache after PRES and evaluated its impact using validated questionnaires.

ResultsOf the 27 cases detected, after excluding 16 patients (11 deceased and 5 lost to follow-up), we evaluated 11 patients with a mean age of 38 (14) years; 63.6% were female. After PRES resolution, 9/11 (81.8%) patients presented headache, with migraine-like features in 8/9 (88.9%). Seven patients completed validated questionnaires; on the Migraine Disability Assessment scale, 71.4% (5/7) had moderate–severe disability. The Short Form-36 Health Survey dimensions of general health, physical role, and vitality reflected a deterioration in the quality of life.

ConclusionsOur data suggest that headache is a potential sequela of PRES that could imply subsequent disability. Migraine-like features point to the existence of shared pathophysiological mechanisms with migraine, which may mainly involve vascular and endothelial functions; however, more studies are needed.

El síndrome de encefalopatía posterior reversible (PRES) se caracteriza por una desregulación cerebrovascular reversible, en el que la cefalea es un síntoma cardinal. Dado que la cefalea como secuela del PRES no ha sido sistemáticamente estudiada, nuestro objetivo fue explorar su prevalencia, características e impacto.

MétodosRetrospectivamente se registraron 27 pacientes con diagnóstico de PRES entre abril-2018 y enero-2022. Se describieron las características demográficas y clínicorradiológicas de la hospitalización. Se evaluó la presencia de cefalea e impacto mediante la escala Migraine Dissability Assessment Scale (MIDAS), Headache Impact Test (HIT-6), SF36_v2, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) y Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI).

ResultadosSe incluyeron 27 pacientes con diagnóstico de PRES, tras excluir la mortalidad intrahospitalaria y las pérdidas de seguimiento, se evaluaron 11 pacientes con una edad media de 38±14 años, el 63,6% eran mujeres. De ellos, 3/11 (27,3%) tenían antecedentes de migraña episódica de baja frecuencia. Tras la resolución del PRES, 9/11 pacientes (81,8%) tenían cefalea, siendo episódica (8/9, 88,9%) y de características migrañosas (8/9, 88,9%). Siete pacientes completaron la totalidad de las escalas. El 71,4% (5/7) presentaba una discapacidad moderada/grave en la escala MIDAS. En la SF36_v2, las dimensiones de salud general, rol físico y vitalidad reflejaban un deterioro en la calidad de vida. A parte de la cefalea, no se reportaron otras secuelas relevantes salvo epilepsia estructural en 2 pacientes. Ningún paciente recibió tratamiento específico para la cefalea.

ConclusiónNuestros datos sugieren una elevada prevalencia de cefalea como potencial secuela del PRES. Las características migrañosas podrían sugerir un mecanismo fisiopatológico común con la migraña que involucre disfunción vasculo-endotelial.

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) is a neurological disorder consisting in cerebrovascular dysregulation with reversible subcortical vasogenic brain edema characterized by acute or subacute neurological symptoms (e.g., seizures, encephalopathy, headache, visual disturbances, and focal neurological deficits). PRES occurs in the context of endothelial injury related to blood pressure changes and/or direct effects of inflammatory processes, leading to breakdown of the blood–brain barrier and subsequent brain edema.

PRES prognosis is determined by the underlying condition, and the main etiologies are renal failure, blood pressure fluctuations, use of cytotoxic drugs, autoimmune disorders, and eclampsia.1,2 No long-term study has examined the prevalence of headache that can emerge and persist after the remission of the acute phase of a PRES episode. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the prevalence, characteristics, and impact of headache as a possible sequela of PRES.

MethodsWe retrospectively recruited, through chart review, all consecutive patients diagnosed with PRES and attended at our hospital from October 2018 to January 2022. We collected demographic, clinical, and radiological data from the acute phase of PRES. We followed up with patients in March 2022 to assess presence of headache after PRES, and its characteristics and impact, using validated questionnaires: Headache Impact Test-6 (HIT-6), Migraine Disability Assessment Test (MIDAS), Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). The study was approved by the Vall d’Hebron Ethics Committee [PR(AG)24/2022]. All patients gave informed consent. Anonymized data supporting this study's findings are available for any qualified investigator upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Statistical analysisThe Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests were used to assess normality of continuous variables. Categorical variables were presented as absolute values and percentages, and continuous variables as median (interquartile range [IQR]) or mean (standard deviation [SD]), as indicated. Statistical significance for intergroup differences was assessed with the Pearson χ2 test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables, and with the Mann–Whitney U test, t test, or ANOVA/Kruskal–Wallis test, as appropriate, for continuous variables. P values <.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS statistics software, version 25.

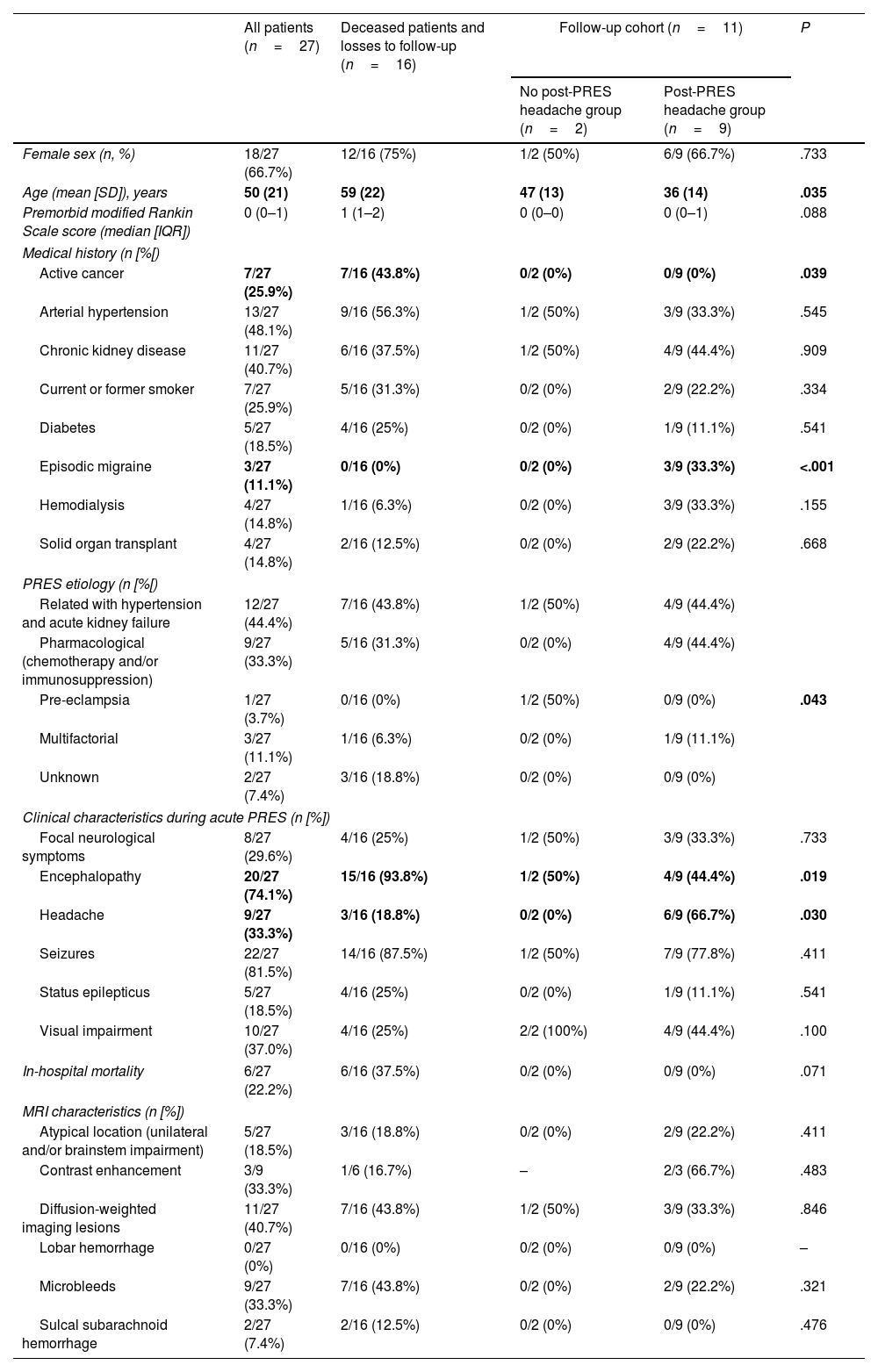

ResultsFrom October 2018 to January 2022, all of the 27 adult patients who were admitted to our institution with a diagnosis of PRES were included in the study. Mean age was 50 (21) years, and 66.7% (18/27) were female. The mean follow-up time was 16 (14) months. Table 1 summarizes the baseline demographic, clinical, and radiological characteristics of acute PRES. We excluded 16 patients due to death (11/27, 40.7%) or loss to follow-up (5/27, 18.6%), including 11 patients in the analysis. Of these, 9 (81.8%) reported post-PRES headache that emerged or persisted immediately after acute PRES.

Baseline and hospitalization characteristics of our cohort of patients with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome.

| All patients (n=27) | Deceased patients and losses to follow-up (n=16) | Follow-up cohort (n=11) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No post-PRES headache group (n=2) | Post-PRES headache group (n=9) | ||||

| Female sex (n, %) | 18/27 (66.7%) | 12/16 (75%) | 1/2 (50%) | 6/9 (66.7%) | .733 |

| Age (mean [SD]), years | 50 (21) | 59 (22) | 47 (13) | 36 (14) | .035 |

| Premorbid modified Rankin Scale score (median [IQR]) | 0 (0–1) | 1 (1–2) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–1) | .088 |

| Medical history (n [%[) | |||||

| Active cancer | 7/27 (25.9%) | 7/16 (43.8%) | 0/2 (0%) | 0/9 (0%) | .039 |

| Arterial hypertension | 13/27 (48.1%) | 9/16 (56.3%) | 1/2 (50%) | 3/9 (33.3%) | .545 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 11/27 (40.7%) | 6/16 (37.5%) | 1/2 (50%) | 4/9 (44.4%) | .909 |

| Current or former smoker | 7/27 (25.9%) | 5/16 (31.3%) | 0/2 (0%) | 2/9 (22.2%) | .334 |

| Diabetes | 5/27 (18.5%) | 4/16 (25%) | 0/2 (0%) | 1/9 (11.1%) | .541 |

| Episodic migraine | 3/27 (11.1%) | 0/16 (0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 3/9 (33.3%) | <.001 |

| Hemodialysis | 4/27 (14.8%) | 1/16 (6.3%) | 0/2 (0%) | 3/9 (33.3%) | .155 |

| Solid organ transplant | 4/27 (14.8%) | 2/16 (12.5%) | 0/2 (0%) | 2/9 (22.2%) | .668 |

| PRES etiology (n [%[) | |||||

| Related with hypertension and acute kidney failure | 12/27 (44.4%) | 7/16 (43.8%) | 1/2 (50%) | 4/9 (44.4%) | .043 |

| Pharmacological (chemotherapy and/or immunosuppression) | 9/27 (33.3%) | 5/16 (31.3%) | 0/2 (0%) | 4/9 (44.4%) | |

| Pre-eclampsia | 1/27 (3.7%) | 0/16 (0%) | 1/2 (50%) | 0/9 (0%) | |

| Multifactorial | 3/27 (11.1%) | 1/16 (6.3%) | 0/2 (0%) | 1/9 (11.1%) | |

| Unknown | 2/27 (7.4%) | 3/16 (18.8%) | 0/2 (0%) | 0/9 (0%) | |

| Clinical characteristics during acute PRES (n [%]) | |||||

| Focal neurological symptoms | 8/27 (29.6%) | 4/16 (25%) | 1/2 (50%) | 3/9 (33.3%) | .733 |

| Encephalopathy | 20/27 (74.1%) | 15/16 (93.8%) | 1/2 (50%) | 4/9 (44.4%) | .019 |

| Headache | 9/27 (33.3%) | 3/16 (18.8%) | 0/2 (0%) | 6/9 (66.7%) | .030 |

| Seizures | 22/27 (81.5%) | 14/16 (87.5%) | 1/2 (50%) | 7/9 (77.8%) | .411 |

| Status epilepticus | 5/27 (18.5%) | 4/16 (25%) | 0/2 (0%) | 1/9 (11.1%) | .541 |

| Visual impairment | 10/27 (37.0%) | 4/16 (25%) | 2/2 (100%) | 4/9 (44.4%) | .100 |

| In-hospital mortality | 6/27 (22.2%) | 6/16 (37.5%) | 0/2 (0%) | 0/9 (0%) | .071 |

| MRI characteristics (n [%]) | |||||

| Atypical location (unilateral and/or brainstem impairment) | 5/27 (18.5%) | 3/16 (18.8%) | 0/2 (0%) | 2/9 (22.2%) | .411 |

| Contrast enhancement | 3/9 (33.3%) | 1/6 (16.7%) | – | 2/3 (66.7%) | .483 |

| Diffusion-weighted imaging lesions | 11/27 (40.7%) | 7/16 (43.8%) | 1/2 (50%) | 3/9 (33.3%) | .846 |

| Lobar hemorrhage | 0/27 (0%) | 0/16 (0%) | 0/2 (0%) | 0/9 (0%) | – |

| Microbleeds | 9/27 (33.3%) | 7/16 (43.8%) | 0/2 (0%) | 2/9 (22.2%) | .321 |

| Sulcal subarachnoid hemorrhage | 2/27 (7.4%) | 2/16 (12.5%) | 0/2 (0%) | 0/9 (0%) | .476 |

Bold values denote statistical significance at the p < 0.05 level.

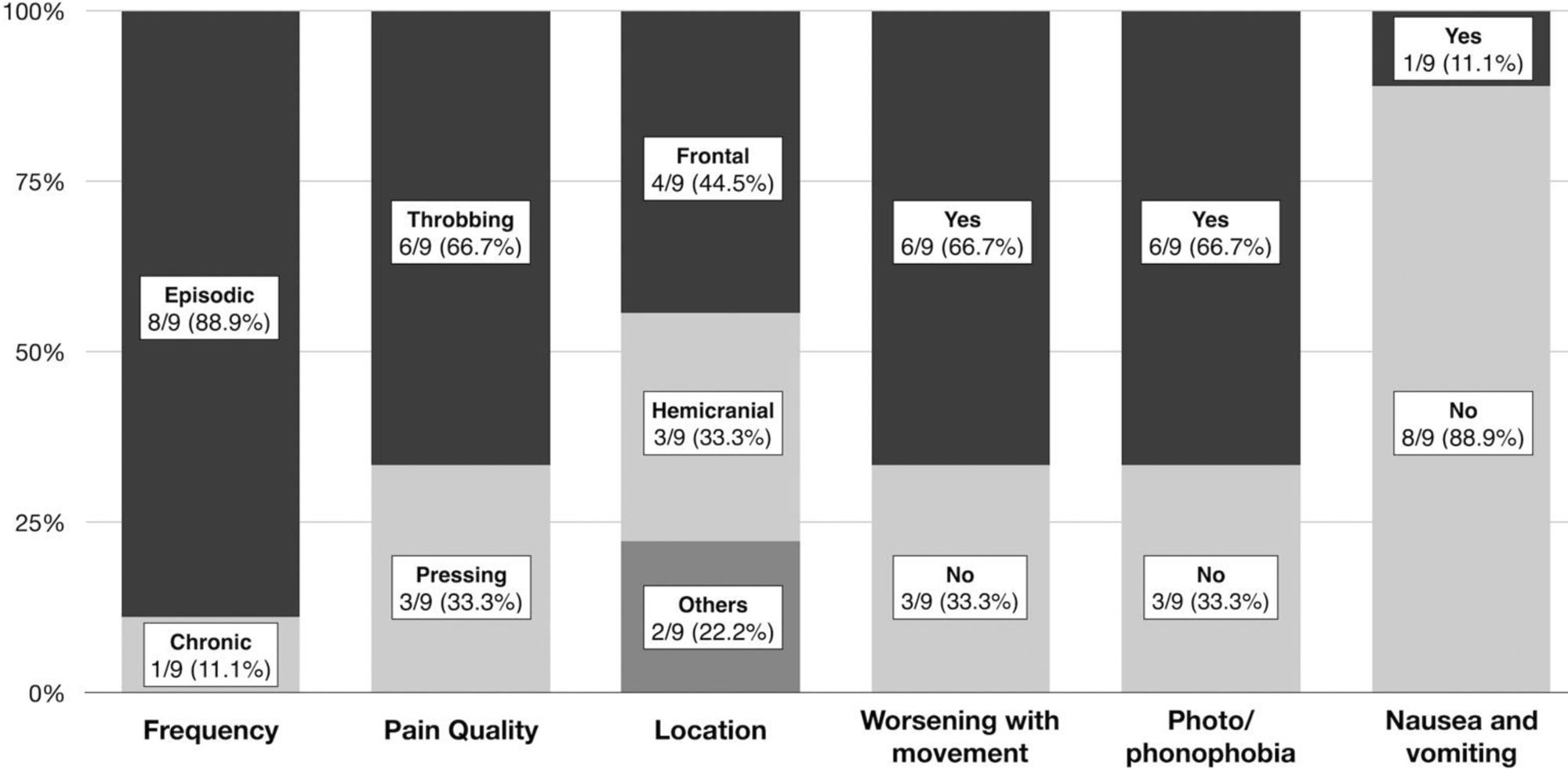

In the subgroup of patients with post-PRES headache, the mean age was 36 (14) years, 66.7% (6/9) were female, and 3/9 patients (33.3%) had a personal history of episodic migraine. No patient had a history of chronic migraine. Migraine-like features were predominant and the headache characteristics are detailed in Fig. 1. Among patients with no previous history of migraine, 4/6 (66.6%) fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of the International Classification of Headache Disorders, third edition (ICHD-3) for migraine without aura.3

Patients who reported post-PRES headache were younger (P=.035), presented etiologies unrelated to presence of an active cancer (P=.039), and more frequently presented headache during the acute phase (P=.030) (Table 1). No patient received specific treatment and/or follow-up for headache after hospital discharge. Other than headache, no other relevant sequelae were reported, except for structural epilepsy in 2/11 patients (18.2%).

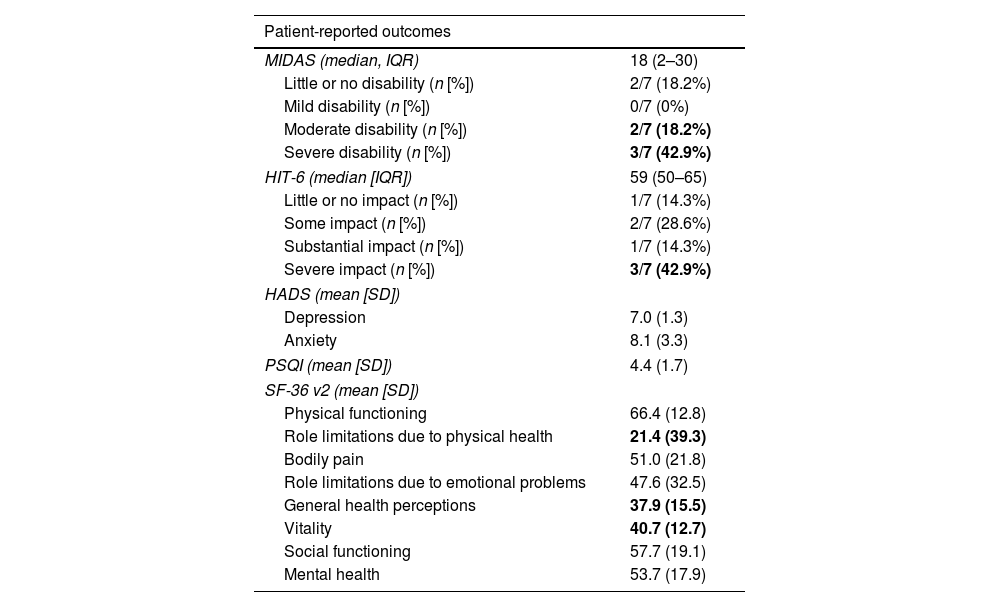

With regard to headache impact, the median MIDAS score was 18 (IQR, 2–30), and 5/7 (71.4%) had moderate or severe disability. The median HIT-6 score was 59 (IQR, 50–65), and 3/7 patients (42.9%) had severe impact. In the comprehensive assessment of patient-reported outcomes (Table 2): (1) sleep quality and patterns were acceptable according to the PSQI score; (2) HADS score identified 2/9 patients (28.6%) with clinically significant depression and 3/9 patients (42.9%) with clinically significant anxiety; (3) on the SF-36, the items role limitations due to physical health (mean, 21.4 [39.3]), vitality (40.7 [12.7]), and general health perceptions (37.9 [15.5]) were moderately impaired.

Patient-reported outcomes.

| Patient-reported outcomes | |

|---|---|

| MIDAS (median, IQR) | 18 (2–30) |

| Little or no disability (n [%]) | 2/7 (18.2%) |

| Mild disability (n [%]) | 0/7 (0%) |

| Moderate disability (n [%]) | 2/7 (18.2%) |

| Severe disability (n [%]) | 3/7 (42.9%) |

| HIT-6 (median [IQR]) | 59 (50–65) |

| Little or no impact (n [%]) | 1/7 (14.3%) |

| Some impact (n [%]) | 2/7 (28.6%) |

| Substantial impact (n [%]) | 1/7 (14.3%) |

| Severe impact (n [%]) | 3/7 (42.9%) |

| HADS (mean [SD]) | |

| Depression | 7.0 (1.3) |

| Anxiety | 8.1 (3.3) |

| PSQI (mean [SD]) | 4.4 (1.7) |

| SF-36 v2 (mean [SD]) | |

| Physical functioning | 66.4 (12.8) |

| Role limitations due to physical health | 21.4 (39.3) |

| Bodily pain | 51.0 (21.8) |

| Role limitations due to emotional problems | 47.6 (32.5) |

| General health perceptions | 37.9 (15.5) |

| Vitality | 40.7 (12.7) |

| Social functioning | 57.7 (19.1) |

| Mental health | 53.7 (17.9) |

MIDAS (Migraine Disability Assessment): little or no disability (0–5), mild (6–10), moderate (11–20), and severe (>20). HIT-6 (Headache Impact Test): little or no impact (<50), some impact (50–55), substantial impact (56–59), and severe impact (>59). SF-36 v2 (Short Form-36 Health Survey): general population, mean of 50 and SD of 10 for all scales. Scores typically range from 20 to 60, with higher scores indicating better health. HADS (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale): normal (0–7), mild (8–10), moderate (11–14), severe (15–21). PSQI (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index): significant sleep disturbance (>5).

Bold values denote statistical significance at the p < 0.05 level.

Our study shows that headache is a potential sequela of PRES that could emerge in up to 80% of the patients discharged. Post-PRES headache habitually appears in young patients with a non-oncological etiology, and presence of migraine-like features is common. Among the patients evaluated, post-PRES headache was associated with moderate–severe disability with quality-of-life impairment.

Although PRES prognosis is determined by the underlying condition, it has been considered a reversible disease. However, neurological sequelae may persist, including unprovoked seizures with subsequent epilepsy development (2.4%–3.9%) and mild cognitive impairment (10%–20%).2,4,5 According to our data, headache may be added as a potential sequela of PRES.

Headache attributed to cranial and/or cervical vascular disorder is included in the ICHD-3, with no mention of PRES as a possible etiology.3 Although headache has been addressed as a sequela of other diseases of vascular-endothelial origin, such as reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome,6 specific data about post-PRES headache are lacking. Our study is the first to describe the characteristics of headache associated with PRES, observing migraine-like features even in patients without a previous personal history of headache. This fact could indicate the existence of shared pathophysiological mechanisms with migraine or the possibility that PRES may activate a latent predisposition to migraine. Our study also observed that post-PRES headache can be disabling, prompting clinicians to better understand, recognize, and treat this entity.

Despite the fact that patients with post-PRES headache were at an age when migraine may still start, most of these patients had no prior history of migraine. Even in this case, PRES would have been the main trigger factor for development of the disease. In addition, patients noted moderate disability (as shown in the patient-reported outcomes), which must be therapeutically addressed. Prospective studies are needed to thoroughly depict headache associated with PRES, and to determine whether endothelial dysregulation in PRES may either trigger latent migraine in predisposed patients or lead to a specific post-PRES secondary headache.

Our study presents the limitations inherent to a retrospective analysis and lacks sufficient statistical power given the small size of study subgroups. Finally, the study was performed at a single center and the results must be reproduced in multicenter studies to confirm our findings.

ConclusionsOur data suggest a high prevalence of headache with a migraine-like phenotype as a sequela in PRES survivors. This observation should facilitate early diagnosis and lead to adequate treatment of post-PRES headache to improve the quality of life of our patients. Migraine-like features suggest the existence of shared pathophysiological mechanisms with migraine, which may mainly involve vascular and endothelial functions.

FundingNone declared.

Authors’ contributionsMR-G, EC, and PP-R contributed to the conception and design of the study, drafted the manuscript, and prepared the figures. MR-G, EC, AA, MT-F, and PP-R contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interestMR-G has no conflicts of interest.

EC has received honoraria as speaker from Novartis, Chiesi, Lundbeck, and Medscape. He is a Junior Editor for Cephalalgia. He is a member of the Communication Committee of the European Academy of Neurology.

AA and MT-F report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

PP-R has received honoraria as a consultant and speaker for AbbVie, Amgen, Biohaven, Chiesi, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Medscape, Novartis, and Teva. Her research group has received research grants from AbbVie, Novartis, Teva, AGAUR, FEDER RIS3CAT, La Caixa Foundation, Migraine Research Foundation, Instituto Investigación Carlos III, EraNet Neuron, International Headache Society, MICINN, PERIS; and has received funding for clinical trials from Alder, Biohaven, Electrocore, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Novartis, and Teva. She is the Honorary Secretary of the Executive Board of the International Headache Society. She is a member of the editorial board of Revista de Neurologia. She is an associate editor for Cephalalgia, Frontiers in Neurology, Headache, and Neurologia, and is a scientific advisor of The Journal of Headache and Pain. She is a member of the Clinical Trials Guidelines Committee of the International Headache Society. She has edited the Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Headache of the Spanish Society of Neurology. She is the founder of the website www.midolordecabeza.org. She does not own stock in any pharmaceutical company.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.