Muslims all over the world practice fasting during Ramadan yearly. A plethora of studies have reported severe worsening of migraine attacks cases due to fasting. The aim is to investigate the effect of Ramadan fasting on migraine frequency and severity among practicing Muslim migraine sufferers.

MethodsThis is a cross-sectional study conducted during the month of Ramadan of the year 2021. This research project has included adult patients meeting the migraine criteria of “International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition”. The frequency and severity of migraine headache were compared to the month preceding Ramadan. In order to analyse the factors associated with breaking the fast motivated by migraine headache during Ramadan, a logistic regression analysis was performed.

ResultsThe study has included 101 migraine sufferers with a clear female predominance. The average duration of migraine was 9±2 years. Compared to the month of Shaban, we noted an increase in the number of attacks, the number of headache days, and the number of days with analgesic medication taken to relieve the attacks. However, the severity and duration of headache did not change significantly between the two months. Most patients changed their eating and sleeping habits during Ramadan. Twenty-two patients broke the fast for several days due to headaches. Ramadan fasting aggravates the frequency of migraine attacks among practicing Algerian Muslims.

ConclusionPhysicians should educate their migraine patients on the importance of lifestyle measures to better manage their headaches during Ramadan.

Los musulmanes de todo el mundo practican el ayuno durante el Ramadán anualmente. Una gran cantidad de estudios han informado un empeoramiento severo de los casos de ataques de migraña debido al ayuno. El objetivo es investigar el efecto del ayuno de Ramadán sobre la frecuencia y la gravedad de la migraña entre los musulmanes practicantes que sufren de migraña.

MétodosSe trata de un estudio transversal realizado durante el mes de Ramadán del año 2021. Este proyecto de investigación ha incluido a pacientes adultos que cumplían con los criterios de migraña de la International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. La frecuencia y la gravedad de la migraña se compararon con el mes anterior al Ramadán. Para analizar los factores asociados a la ruptura del ayuno motivado por la migraña durante el Ramadán, se realizó un análisis de regresión logística.

ResultadosEl estudio ha incluido a 101 pacientes migrañosos, con un claro predominio femenino. La duración media de la migraña fue de 9±2años. En comparación con el mes de Shaban, notamos un aumento en la cantidad de ataques, la cantidad de días con dolor de cabeza y la cantidad de días con medicamentos analgésicos para aliviar los ataques. Sin embargo, la severidad y la duración del dolor de cabeza no cambiaron significativamente entre los dos meses. La mayoría de los pacientes cambiaron sus hábitos alimentarios y de sueño durante el Ramadán. Veintidós pacientes rompieron el ayuno durante varios días debido a dolores de cabeza. El ayuno de Ramadán agrava la frecuencia de los ataques de migraña entre los musulmanes argelinos practicantes.

ConclusiónLos médicos deben educar a sus pacientes con migraña sobre la importancia de las medidas de estilo de vida para controlar mejor sus dolores de cabeza durante el Ramadán.

Migraine is one of the most frequent chronic neurological pathologies.1 Despite its benign nature, migraine is a debilitating health condition with a considerable impact on the quality of life of patients.2 It is characterized by headaches lasting 4–72h, accompanied with vomiting and/or photophonophobia, between which the patient does not suffer.3 The prevalence of migraine is estimated at 12% with a clear female predominance (14% versus 6%).4

Migraine has significant socio-economic consequences with increased frequency of absenteeism, reduced work productivity, and increased healthcare costs.5

Muslims practice fasting every year during Ramadan. As a result, they abstain from food and drink from dawn until sunset.6 As the Islamic calendar is lunar, the duration of the fast varies from year to year and from one country to another, ranging from 11 a.m. to more than 8 p.m.7

Muslims who fast usually eat only two meals a day, one after sunset and the other just before dawn.8 They also practice night prayer, which leads to changes in the usual sleep cycle.9 Fasting is not an obligation for sick people and children before puberty. It is even not recommended for anyone with a chronic disease at the risk of decompensation of their disease.

Several studies have reported a worsening of migraine attacks by fasting.10–12 The factors incriminated in this process are essentially represented by the sudden withdrawal from caffeine and tobacco13 as well as sleep cycle disturbances.10 Therefore, the exact physiopathogenic mechanisms are still hypothetical.

Given that the Muslim community worldwide is estimated at approximately 1.8 billion people,14 and that most of them fast during the whole month of Ramadan, it was essential to study the effect of Ramadan fasting on the frequency of migraine attacks among practicing Muslim migraine sufferers.

MethodsThis is a descriptive cross-sectional study conducted at the neurology department of the University Hospital Center of Oran in Algeria during the two months of Shaban and Ramadan 1442, corresponding to the solar period from March 15 to May 12, 2021. The average daily duration of fasting during Ramadan was 15h, and the daytime temperature varied between 22 and 26°C.

Sampling criteriaWe included Muslim patients aged 18–65, fasting in Ramadan, and meeting the diagnostic criteria for migraine with or without aura evolving for more than a year.15

Non-inclusion criteriaThis study did not include patients suffering from non-migraine headaches, patients with a history of head trauma in the year preceding the survey, and pregnant or breastfeeding patients. We did not include patients with cognitive impairment preventing them from correctly completing the questionnaire and headache calendar.

The patients were recruited consecutively during Rajab (the month preceding Shaban) and were called for a first check-up at the end of Shaban, then for a second check-up at the end of Ramadan.

To assess the frequency of migraine attacks, we gave our patients diaries to mention the date, time, duration, and severity of the attacks.

To study the impact of fasting and changing habits among patients during Ramadan, we distributed a questionnaire to patients. The questionnaire included information on migraine attacks during Ramadan and Shaban, demographic data such as age, gender, and socio-economic status.

The frequency and severity of migraine attacks and the number of days of analgesic drugs intake during Ramadan were compared to data obtained from Shaban. The number of days with migraine attacks, justifying the interruption of fasting was reported. The severity of attacks was measured using the visual analogic scale (VAS). Its score varies from 0 (no pain) to 10 (the worst pain imaginable). To exclude secondary headaches, when the symptomatology was atypical, additional examinations were carried out.

DefinitionsMigraine without aura has been defined as “a recurrent headache manifested by attacks lasting from 4 to 72h. Typical features of headache are as follows: unilateral topography, pulsatile type, moderate or severe intensity, worsening by routine physical activity and association with symptoms such as nausea and/or photophobia and phonophobia” (ICHD, 3rd edition, 2015).

Migraine with aura has been defined as the occurrence of recurrent attacks, lasting several minutes of fully reversible unilateral symptoms, visual, sensory, or other, which usually develop gradually and are often followed by a headache and associated signs of migraine (ICHD, 3rd edition, 2015).

Statistical analysisData was entered and analyzed using statistical software (SPSS 22.0). Continuous variables were expressed as means, while categorical variables were expressed as percentages. The variables used for the comparisons were the number, duration, and severity of the attacks, the number of days of taking analgesics to relieve the migraine attacks during the two months of Shaban and Ramadan. Statistical analyzes included parametric tests to compare means (paired and unpaired two-sample t-test), nonparametric tests to compare medians (Wilcoxon test and Mann–Whitney test), and chi-square to test relationships between categorical variables. For all tests, p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

A logistic regression analysis was performed to analyze the factors associated with breaking the fast enhanced by migraine attacks during Ramadan. The initial model included all the factors statistically linked to breaking the fast at the 20% threshold. The selection of the remaining variables in the final model was applied according to a top-down Wald strategy. Various factors were retained at the 5% threshold.

ResultsDuring Rajab 1442 (from February 14 to March 14, 2021), 141 patients consulted the neurology department of the University Hospital Center of Oran for headaches. We excluded 15 patients with tension headaches, three patients with trigeminal neuralgia, and 17 patients with secondary headaches. Five patients meeting migraine criteria were also excluded because the diagnosis was less than a year old.

A total of 101 individuals meeting the criteria for migraine with or without aura evolving for at least one year were included in the study. These patients were evaluated at the end of Shaban and then at the end of Ramadan.

The average age bracket of our patients was 34.2±7.1 years old with extreme ranging from 18 to 51 years old. We noted a clear female predominance (78.2%: 79 women/22 men). Nearly two-thirds of the participants were married (64.3%: 65/101), and 62 (62.4%) had a full-time job.

Regarding our patients’ lifestyle: 14 (13.9%) were active smokers, 51 (50.5%) were caffeine consumers, 26 (25.7%) were exposed to daily stress, 31 (30.7%) were overweight, and only 18 (17.8%) practiced a sports activity regularly.

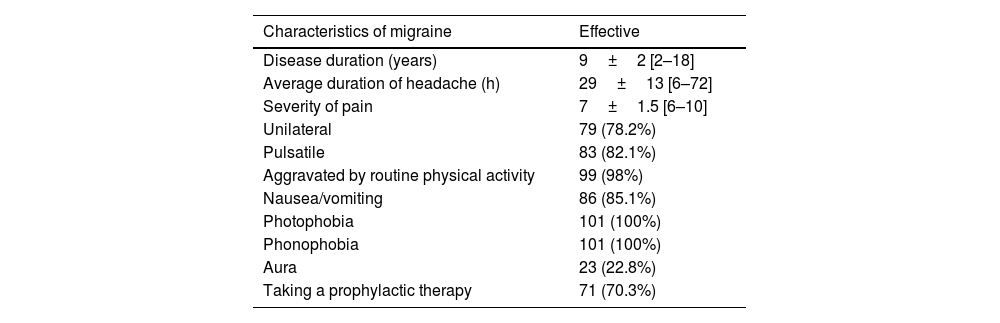

The average duration of migraine evolution was 9±2 years with extreme ranging from 2 to 18 years. The characteristics of migraine were noted during the first consultation in Rajab, as summarized in Table 1.

Characteristics of migraine in the study population.

| Characteristics of migraine | Effective |

|---|---|

| Disease duration (years) | 9±2 [2–18] |

| Average duration of headache (h) | 29±13 [6–72] |

| Severity of pain | 7±1.5 [6–10] |

| Unilateral | 79 (78.2%) |

| Pulsatile | 83 (82.1%) |

| Aggravated by routine physical activity | 99 (98%) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 86 (85.1%) |

| Photophobia | 101 (100%) |

| Phonophobia | 101 (100%) |

| Aura | 23 (22.8%) |

| Taking a prophylactic therapy | 71 (70.3%) |

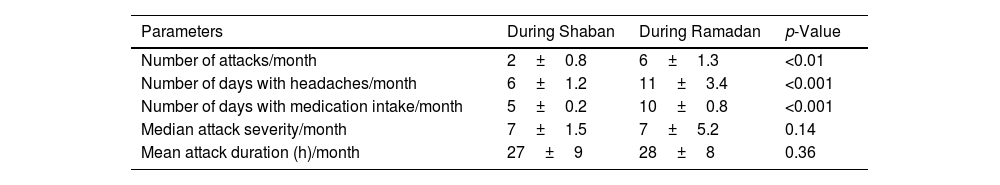

We compared the clinical characteristics of migraine headaches between the two months: Shaban and Ramadan and assessed their impact on fasting (Table 2). We noted a statistically significant increase in the monthly frequency of attacks (p<10−2), the number of headache days/month (p<10−3), and the number of days with pain medication taken to relieve the attacks (p<10−3). However, the median attacks severity and the mean headache duration did not change significantly between the two months (p=0.14 and p=0.36 respectively).

Comparison of the characteristics of migraine between Shaban and Ramadan.

| Parameters | During Shaban | During Ramadan | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of attacks/month | 2±0.8 | 6±1.3 | <0.01 |

| Number of days with headaches/month | 6±1.2 | 11±3.4 | <0.001 |

| Number of days with medication intake/month | 5±0.2 | 10±0.8 | <0.001 |

| Median attack severity/month | 7±1.5 | 7±5.2 | 0.14 |

| Mean attack duration (h)/month | 27±9 | 28±8 | 0.36 |

During Ramadan, most of our patients have changed their eating and sleeping habits. Indeed, 89 (88.1%) patients declared a reduction in hours of sleep. Seventy-one (70.3%) patients reported withdrawal from coffee or tea, 62 (61.4%) patients reported a decrease in beverage consumption, and 59 (58.4%) reported an increase in sweets consumption.

More than two-thirds of the participants 79 (78.2%) continued to fast despite the migraine attacks. Of the remaining 22 participants, 13 (59%) broke the fast for three days or less, and 7 patients (31.8%) broke the fast for 4–10 days. Only 2 patients could not fast for the whole month because of the severity of the headaches, which were accompanied by vomiting and photophobia. The breaking of the fast was maximal during the first week of Ramadan.

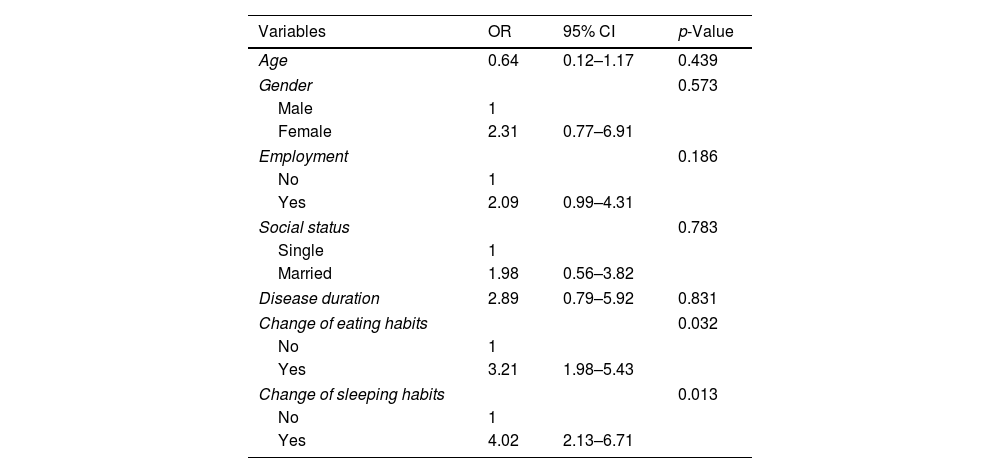

We performed a multivariate analysis by logistic regression to identify the factors associated with breaking the fast. The selected variables in the final model were change in eating (p=0.032) and sleep habits (0.013). However, age, employment, social status and disease duration were not associated with breaking the fast (Table 3).

Results of multivariate analysis by logistic regression.

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.64 | 0.12–1.17 | 0.439 |

| Gender | 0.573 | ||

| Male | 1 | ||

| Female | 2.31 | 0.77–6.91 | |

| Employment | 0.186 | ||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 2.09 | 0.99–4.31 | |

| Social status | 0.783 | ||

| Single | 1 | ||

| Married | 1.98 | 0.56–3.82 | |

| Disease duration | 2.89 | 0.79–5.92 | 0.831 |

| Change of eating habits | 0.032 | ||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 3.21 | 1.98–5.43 | |

| Change of sleeping habits | 0.013 | ||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 4.02 | 2.13–6.71 | |

Fasting has been incriminated by several studies in triggering certain types of headaches such as migraine.10 Indeed, an Indian study reported higher rates of emergency department visits for headaches during Ramadan in Muslim communities in India.16 In the latest international classification, headache attributed to fasting has been individualized as an entity in its own right, forming part of the headache attributed to a homeostasis disorder. They are described as diffuse non-throbbing headaches, usually mild to reduced, occurring during and after fasting for at least 8h, and disappearing after eating.15 These headaches, thus, differ from migraine whose character is pulsatile and the intensity is generally moderate-to-severe.

Migraine is a common neurological disease, especially among young adults. Its prevalence is estimated at 12% with a clear female predominance.4 Despite its frequency, its relationship to fasting in Ramadan has been under-studied in the Muslim community, which is estimated at around 1.8 billion worldwide.14 This is, hence, the first Algerian study aiming to evaluate the impact of fasting during Ramadan on the frequency and severity of migraine attacks in Muslim and practicing patients.

Our study, which included 101 patients, is marked by a clear female predominance (78.2%). This result is compatible with data from the literature.16 Indeed, although migraine can affect men, it is considered a female condition with a higher incidence in women since puberty and throughout life. This is probably related to certain sex hormones known to influence neurotransmitters and neuromediators in the brain.16

Comparing the clinical characteristics of migraine headaches between Shaban and Ramadan, we noted a statistically significant increase in the number of attacks, the number of headache days, and the number of days with pain reliefs against the attacks. At the same time, we did not note any aggravation of migraine attacks’ severity nor in their duration. Our results agree with Abu-Salameh et al.’s findings. The latter reported a three-fold increase (9.4±4.3 days versus 3.7±2.1 days: p<0.001) in the frequency of migraine attacks during Ramadan in a cohort of 30 migraine patients.17 Several studies agree with the fact that fasting is a trigger for headaches, but the pathophysiological mechanisms remain hypothetical.18 Several parameters have been incriminated such as hypoglycemia.19 Indeed, two factors can reduce available glycogen-derived glucose in astrocyte extremities peri-synaptics at the onset of intense synaptic activity, naming prolonged periods of hypoglycemia or glucagon released in the early hours of fasting, as well as prolonged sympathetic activity during long-term fasting. This can also lead to an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory neuromediators, causing network depolarization of neurons and astrocytes and, thus, triggering aura and/or headache.10 Furthermore, other factors are implicated in the onset of headaches during fasting, such as dehydration, caffeine withdrawal, and sleep cycle disturbances.20–22 In contrast to our study, Gabr et al. have found a significant decrease in the number of migraines during Ramadan in a Saudi population.23 These conflicting results may be due to differences in caffeine consumption levels and sleep patterns between the two populations.

In the present study, the multivariate analysis has identified two factors that are, significantly associated with breaking the fast, notably the change in eating and sleep habits. Indeed, 88.1% reported a reduction in hours of sleep, 70.3% reported a decrease in coffee and tea consumption, two-thirds reported a decrease in water intake, and 58.4% reported an increase in consumption of sweets. Our results are similar to those of the study by Al-Hashel et al., conducted in Kuwait on 293 Muslim patients with migraine. Indeed, authors reported that change in sleep and feeding habits together with non-modification of the treatment plan before Ramadan significantly predict breaking fasting due to worsening of migraine headache (p-value=0.041, p-value=0.025; respectively).11 These results could be explained by several hypotheses: first of all, it is commonly accepted that sleep and dehydration are fundamentally linked to the secretion of vasopressin.24 Otherwise, vasopressin supports vasomotor, anti-nociceptive, behavioral control, fluid, and electrolyte balance functions. On the other hand, in synergy with intrinsic cerebral noradrenergic and serotonergic activation, vasopressin forms an important adaptive system to regulate pain and stress response to patients with episodic migraines or chronic headaches.24 This factor could explain the exacerbation of migraine attacks during Ramadan.

Breaking the fast was more frequent during the first week of Ramadan compared to the rest of the month.23 This fact could be explained by a sudden caffeine withdrawal, especially since coffee consumption in Algerian society is quite high25

Our results agree with those of Ragab et al. who observed that the number of attacks was significantly reduced in both the second (median 1, IQR 0–2.25) and the third 10 days of Ramadan (median 1, IQR 1–3) compared with the first 10 days (median 3, IQR 1–5) (p<0.001 for each).26

That said, it must be emphasized that most migraine patients continued to fast, regardless of headache severity and frequency, due to their close spiritual connection to this holy month. This means they are extremely willing to fast despite the deterioration of their state of health. This situation is a challenge for physicians trying to find the best prophylactic therapy for these patients. Accordingly, different modalities of medical therapies should be investigated beforehand in patients suffering from migraine attacks during the period of fasting, offering the best reduction in migraine attacks and their severity.

Medical practitioners should discuss the potential exacerbation of migraines during Ramadan with their patients and educate them on ways to avoid abrupt caffeine withdrawal. For example, introduce them to methods to improve their sleep patterns and how to prevent dehydration. Moreover, an adequate prophylactic treatment should be initiated a few months before Ramadan for best results.

The limitations of the study should be outlined. Indeed, our study is monocentric, having focused on patients recruited at the University Hospital of Oran; the study's respondents may not represent all migraine patients in Algeria. Moreover, we did not study the effect of prophylactic treatments on fasting during Ramadan. Finally, this is a retrospective study and may have recall bias.

ConclusionMigraine attacks are exacerbated by Ramadan fasting among practicing Algerian Muslims. Changes in eating and sleeping habits are predictive factors for breaking the fast during this holy month. Physicians should instruct their migraine patients on the importance of lifestyle measures and prior initiation of prophylactic treatment to better manage their headaches during Ramadan.

Ethics statementThe consent has been obtained from the all patient including in this study.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.