The terms perivascular space or Virchow-Robin space (VRS) refer to the spaces surrounding the vessels supplying the brain parenchyma, and constitute a separate structure from the subarachnoid space. In MRI studies, dilated VRS typically appear as round or linear shapes and are isointense to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) on all sequences. Generally, the parenchyma surrounding these spaces presents normal signal intensity. While they usually appear in typical locations (basal ganglia, subcortical white matter, midbrain), dilated VRS may occur in practically any location.1

Dilated VRS are a frequent neuroimaging finding, and their prevalence is greater in elderly individuals or patients with small-vessel disease, associated with lacunar stroke and vascular leukoencephalopathy.2,3 Despite this, the mechanism by which these spaces become dilated remains unclear; multiple theories have been proposed, including increased arterial wall permeability, alterations in CSF drainage, spiral elongation of blood vessels, and brain atrophy. A correlation has been described between dilated VRS and neuropsychiatric disorders, multiple sclerosis, traumatic brain injuries, and microvascular diseases.1,4 Some of these situations are equivalent in pathological terms to the effects of radiotherapy, such as white matter oedema, demyelination, fibrinoid changes in blood vessels, coagulative necrosis, and cysts with liquefied centres and peripheral gliosis.5 Recently, brain radiotherapy has been proposed as a likely cause of dilated VRS.6,7

We present the case of a 63-year-old man who attended the emergency department due to a seizure in 2012, reporting similar episodes of absence seizures in the previous months, with no other relevant personal history. An emergency head CT scan revealed an intra-axial lesion in the right frontal lobe. The study was subsequently expanded with an MRI scan and a biopsy study, which confirmed the diagnosis of diffuse astrocytoma with foci of anaplastic transformation. Four months later, the patient started chemotherapy (temozolomide) and radiotherapy, with a total dose of 60 Gy in fractions of 2 Gy/day between October and November 2012. The patient subsequently underwent clinical and neuroimaging (MRI) follow-up by the oncology department.

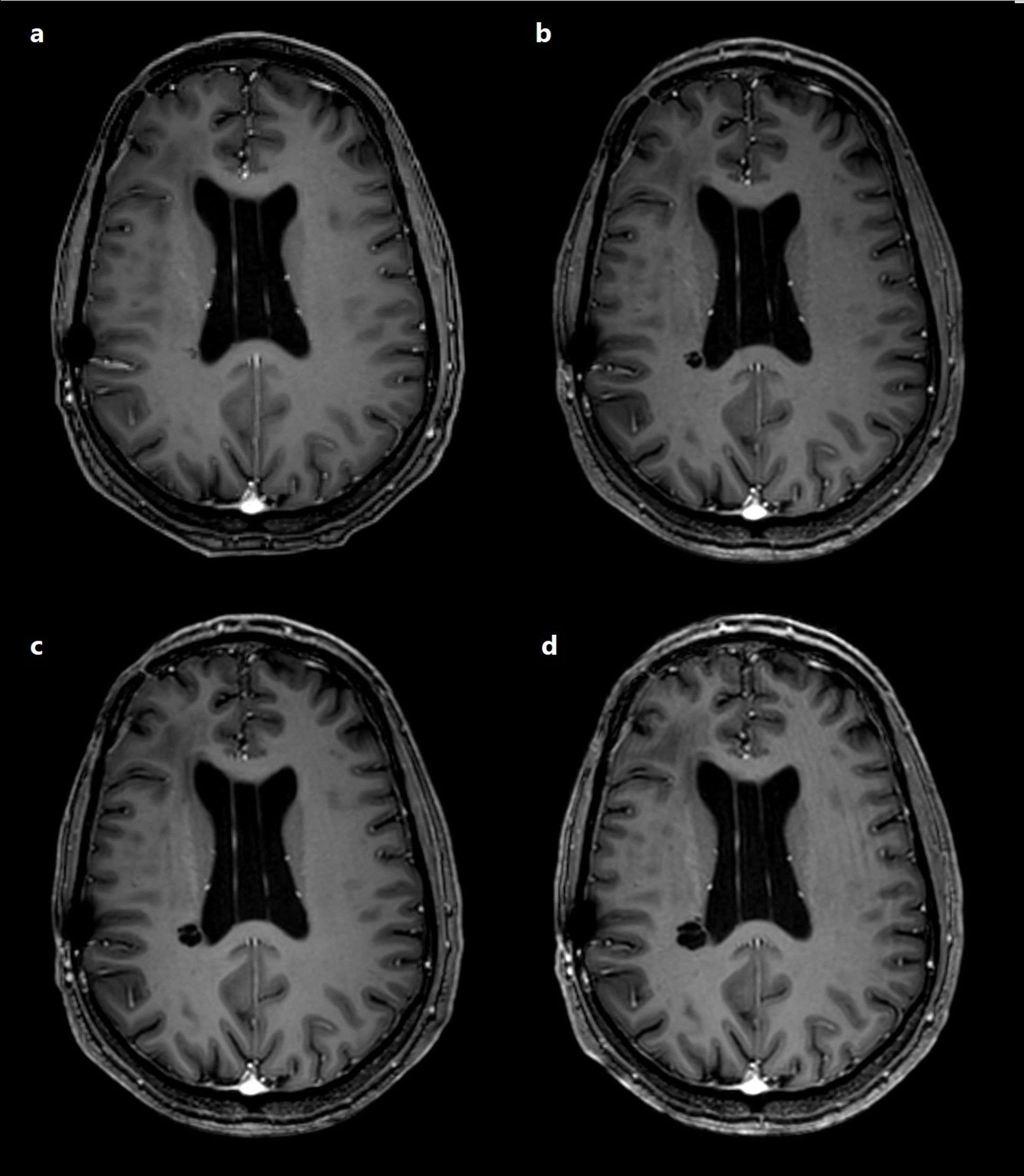

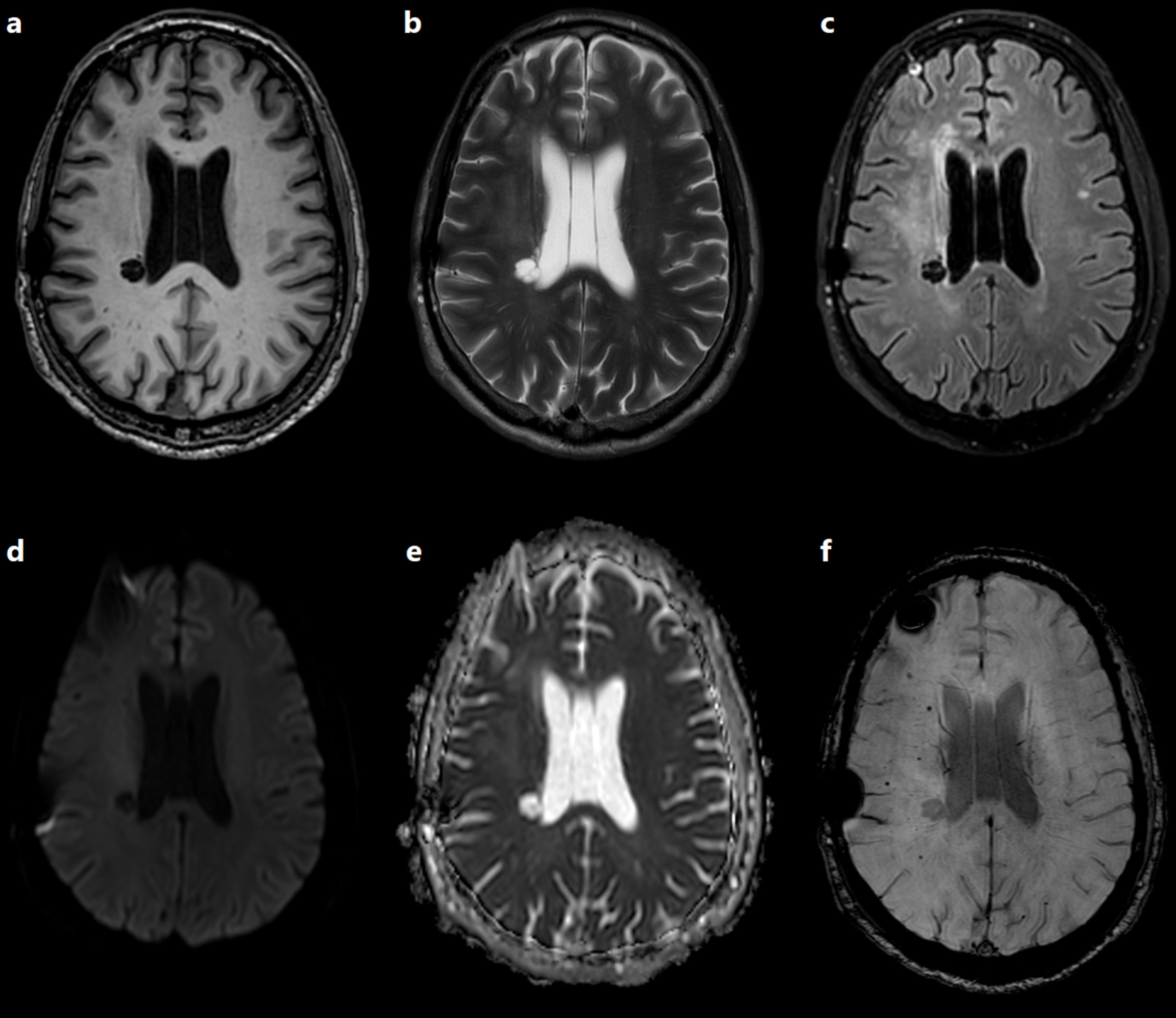

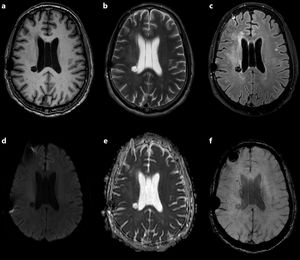

The follow-up brain MRI scan performed in 2017 detected a new cystic lesion in the right corona radiata, which displayed progressive growth in subsequent studies (Fig. 1). Clinical examination identified no new neurological alterations or deficits. The lesion was cystic and septated, isointense to CSF on all sequences, was not surrounded by oedema or gliosis, and presented no diffusion restriction or contrast enhancement. It was located in the radiation field and surrounded by multiple punctiform haemorrhagic foci, visible on magnetic susceptibility sequences, in the adjacent white matter (Fig. 2).8

Status of the lesion in an MRI study performed in 2020. a) Non-contrast T1-weighted 3D-SPGR sequence; b) T2-weighted TSE sequence; c) 3D T2-FLAIR sequence; d) diffusion sequence (b = 1000); e) ADC map; f) magnetic susceptibility sequence. The lesion is isointense to CSF on T1- and T2-weighted sequences (a, b), and presents signal suppression on T2-FLAIR sequences (c), which suggests free water in the centre and absence of peripheral oedema or gliosis; it also presents facilitated diffusion (d, e). The magnetic susceptibility sequence shows hypointense haemorrhagic foci near the lesion, within the radiation field (f).

In the light of these findings, differential diagnosis may include cystic neoplasm, infectious lesions, or ischaemic lesions. Purely cystic brain neoplasms are extremely rare, and the absence of oedema or contrast uptake makes this diagnosis highly unlikely. The lack of associated symptoms or diffusion restriction allows us to rule out such infectious lesions as abscesses. The absence of adjacent or distant white matter alterations and the progressive growth of the lesion favoured a diagnosis of dilated VRS, rather than a lacunar ischaemic lesion.

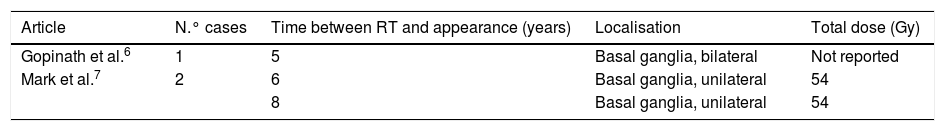

All these findings further support the diagnosis of a benign process, such as new dilated VRS in a patient undergoing radiotherapy. Its localisation, within the radiation field, and the delay between radiotherapy and detection of the lesion (approximately 5 years) are consistent with the findings reported in similar cases by Gopinath et al.6 and Mark et al.7 (Table 1); we therefore consider that radiotherapy probably caused the dilation of the VRS.

In conclusion, understanding of the mechanisms by which radiotherapy acts on the central nervous system and the evidence discussed above lead us to suspect radiation as the cause of the dilated VRS. Although this finding is not pathologically significant, it should be taken into account in the differential diagnosis of patients receiving radiotherapy, in order to prevent misdiagnosis as conditions that may require other courses of action, with potentially harmful consequences.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Please cite this article as: Pérez García MC, Láinez Ramos-Bossini AJ, Martínez Barbero JP. Crecimiento anormal de espacios de Virchow-Robin secundario a radioterapia. Neurología. 2021;36:725–728.