Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is an autoimmune demyelinating disease of the central nervous system typically occurring in childhood and characterised by multifocal white matter involvement. It is usually monophasic, although up to 20% of patients may present recurrence. Between 50% and 75% of cases are associated with history of infection, whether viral (measles, mumps, influenza, hepatitis, herpes) or bacterial (Chlamydia, Legionella, Campylobacter), with Mycoplasma pneumoniae being the most common bacterial cause.1 Cases have also been described of ADEM in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection.2 The aetiopathogenesis of ADEM is unknown; the disease is thought to result from an autoimmune response against infectious agents with epitopes similar to myelin-associated peptides, causing demyelinating lesions.3 The condition may present with a wide range of symptoms. It usually manifests with initially systemic symptoms, followed by acute, rapidly-progressing multifocal neurological symptoms.4–7 As no specific biological markers have been identified, diagnosis is clinical and radiological; furthermore, no diagnostic criteria have been established for adults, unlike in the paediatric population.8 Adults usually present a more aggressive course, with poorer functional outcomes and survival rates (10%-30% mortality).5

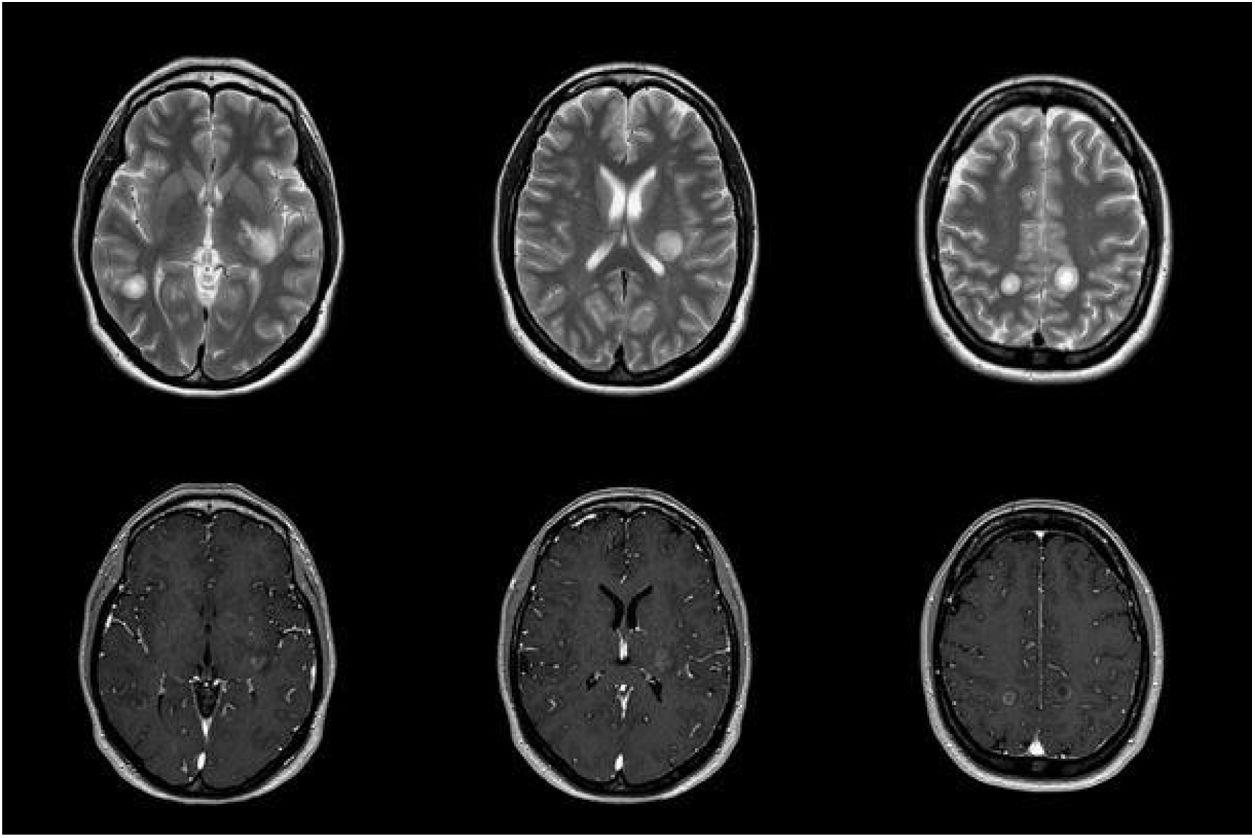

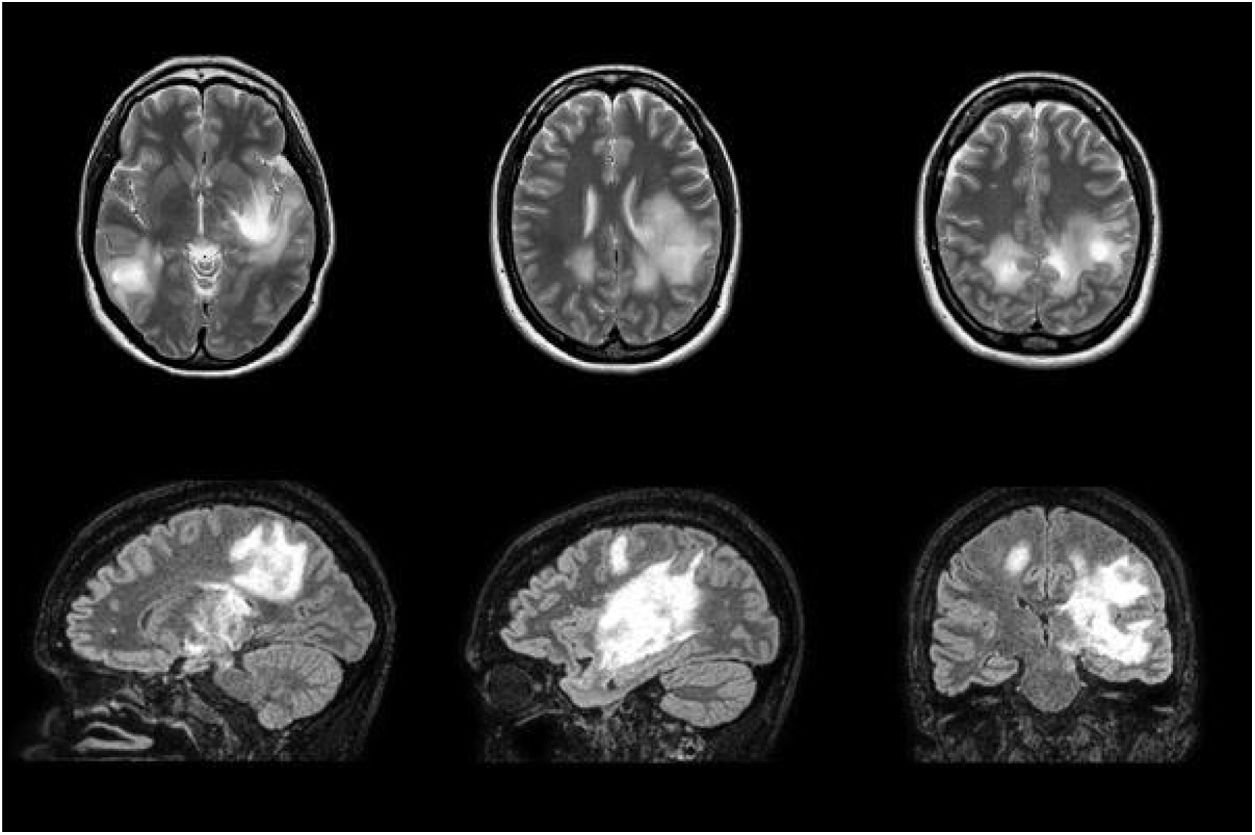

We report the case of a 38-year-old woman who had presented pneumonia 3 weeks previously in the context of an epidemic outbreak in her workplace, receiving treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. She consulted due to one week’s history of blurred vision in the left eye and right-sided faciobrachial paraesthesia. The neurological examination revealed bilateral, asymmetric loss of visual acuity with normal eye fundus, right-sided ataxic hemiparesis, right-sided facial hypoaesthesia, generalised hyperreflexia, and wide-based gait with inability to walk in tandem. Given the current epidemiological situation, we requested SARS-CoV-2 serology and PCR studies, which yielded negative results. Focal neurological signs progressed over the first few days, with the patient presenting sensorimotor aphasia. A brain MRI scan revealed multiple large, oval-shaped lesions in the white matter and basal ganglia; the lesions were hyperintense on T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences, with no mass effect, and displayed peripheral contrast uptake (Fig. 1). A cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed elevated protein levels (0.59 g/L; normal range, 0.35-0.45) with no cells; other analyses (autoimmune tests, culture of mycobacteria, and PCR for Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus agalactiae, Haemophilus influenzae, Listeria monocytogenes, and neurotropic viruses) yielded negative results. Blood serology tests yielded positive results for IgM and IgG antibodies against M. pneumoniae 15 days after the onset of neurological symptoms; the remaining serology studies (HIV, EBV, CMV, Legionella, Chlamydia, Coxiella burnetii) and autoimmune studies yielded negative results. A chest-abdomen-pelvis CT scan and transthoracic echocardiography study identified no abnormalities. We started treatment with 1 g intravenous boluses of methylprednisolone, which had to be discontinued on the third day due to clinical worsening. The patient also did not respond to intravenous immunoglobulins. Plasmapheresis was started, with a good response. We would like to highlight the discrepancy between clinical and radiological findings (Fig. 2), with the patient presenting radiological worsening despite clinical improvement.

Brain MRI scan performed during treatment with intravenous immunoglobulins, showing radiological worsening despite the patient’s favourable clinical progression. The scan revealed multiple hyperintensities on T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences, with diffusion restriction; the largest lesions involve the left basal ganglia and corticosubcortical regions bilaterally.

Clinical presentation is particularly important in ADEM. Fever, headache, and meningeal signs are rare in adult patients. Encephalopathy as the initial symptom may be highly relevant in differential diagnosis with other demyelinating diseases.5 In our patient, the absence of these symptoms and the MRI findings led us to broaden the differential diagnosis to include neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders and autoimmune encephalitis.3,7 Tests for anti-aquaporin-4 (AQP4) antibodies and oligoclonal bands (OCB) in the CSF yielded negative results. Testing for antimyelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibodies is recommended in these cases due to their implications for treatment, prognosis, and risk of recurrence; testing for anti-AQP4 antibodies is also recommended for the differential diagnosis of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders.3 Patients with ADEM rarely present OCBs in the CSF; however, OCB determination may be useful in predicting future risk of multiple sclerosis, a condition that is more frequent in patients with recurrent demyelination testing negative for anti-MOG antibodies.3 The imaging technique of choice is MRI, which frequently reveals hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences. Unlike in multiple sclerosis, MR images of ADEM typically display thalamic lesions, with no “black holes.”6,9 The first-line treatment in the acute management of patients with ADEM is high-dose corticosteroid therapy, frequently with methylprednisolone (maximum dose of 1000 mg/day) for 3 to 5 days. This treatment achieves complete recovery in 50% to 80% of cases. In refractory cases, such as that reported here, plasmapheresis or intravenous immunoglobulins are recommended.7,10 Our patient presented signs of poor prognosis (hyperacute onset, aggressive course, severe focal neurological signs, and lack of response to corticosteroid therapy), despite which she progressed favourably; 6 months after diagnosis, she is oligosymptomatic.10

In conclusion, the highly variable clinical presentation of ADEM and the lack of specific biological markers and established diagnostic criteria for adults make this entity a diagnostic challenge. Identifying adult-onset ADEM and providing early treatment is essential to improving functional and vital prognosis.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez-Montolio J, Ballesta-Martínez S, Martín-Alemán Y, Muñoz-Farjas E. Encefalomielitis aguda diseminada tras infección por Mycoplasma pneumoniae: evolución tórpida, recuperación excelente. Neurología. 2022;37:313–315.