The association of myasthenia gravis (MG) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (overlap syndrome) is infrequent in clinical practice. The available evidence suggests that immunomodulatory therapy has a protective effect in the early stages of motor neuron disease (MND).1,2 We present 3 cases of this overlap syndrome; Table 1 summarises the characteristics of these patients.

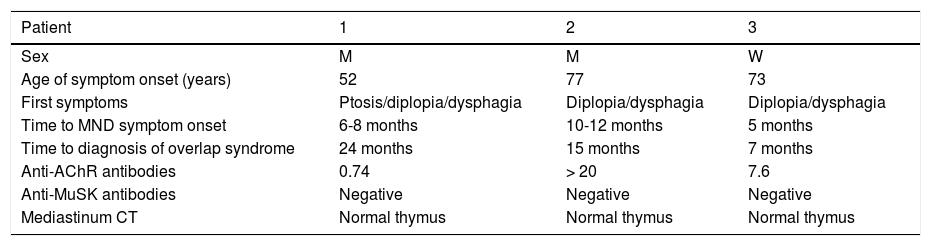

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients.

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | M | M | W |

| Age of symptom onset (years) | 52 | 77 | 73 |

| First symptoms | Ptosis/diplopia/dysphagia | Diplopia/dysphagia | Diplopia/dysphagia |

| Time to MND symptom onset | 6-8 months | 10-12 months | 5 months |

| Time to diagnosis of overlap syndrome | 24 months | 15 months | 7 months |

| Anti-AChR antibodies | 0.74 | > 20 | 7.6 |

| Anti-MuSK antibodies | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Mediastinum CT | Normal thymus | Normal thymus | Normal thymus |

AChR: acetylcholine receptor; CT: computed tomography; M: man; MND: motor neuron disease; MuSK: muscle-specific receptor tyrosine kinase; W: woman.

The patient was a 52-year-old man with initial symptoms of bilateral ptsosis, diplopia, and dysphagia; 6-8 months later, he presented left brachial paresis with thenar atrophy, global hyperreflexia, and increased jaw jerk reflex. 3-Hz repetitive stimulation obtained a decrement of > 10% in the fifth potential in the abductor digiti minimi. Anti-acetylcholine receptor (anti-AChR) antibody titre was 0.74 (positive results, > 0.7), and remained stable in subsequent determinations. Fasciculations and denervation potentials were observed in an electromyography study (EMG) performed 4 months after the initial assessment. At 24 months, the patient met diagnostic criteria for class IIb MG3 and definite ALS, according to the El Escorial criteria.4

Patient 2The patient was a 77-year-old man who developed dysphonia and neurogenic dysphagia with fatigue. He was initially diagnosed class IIb MG: anti-AChR antibody titre was > 20 and 3-Hz repetitive stimulation of the abductor digiti minimi obtained a decrement of > 10% in the fifth potential. Treatment was started with pyridostigmine and oral prednisone, with good clinical response; at 15 months, he presented atrophy of the shoulder and pelvic girdles and right quadriceps, and exacerbation of bulbar symptoms and hyperreflexia. The EMG revealed fasciculations and denervation potentials in the deltoids, medial head of the left gastrocnemius, and the left vastus, and in the tongue.

Patient 3The patient was a 73-year-old woman with dysphonia, neurogenic dysphagia, fatigue, and exertion dyspnoea of progressive onset in the previous 2 months. 3-Hz repetitive stimulation of the facial and accessory nerves obtained a decrement of > 10% in the fifth potential. Anti-AChR antibody titre was 7.6. After diagnosis of class IIb MG,3 combined treatment with pyridostigmine and prednisone was started. Five months after onset, the patient presented anarthria. An EMG study revealed denervation activity and fasciculations in the masseter, tongue, right first interosseous muscle, abductor digiti minimi, and vastus lateralis. The subsequent clinical progression, with lack of response to treatment with immunoglobulins and plasmapheresis, as well as the findings of the neurophysiological study, confirmed the diagnosis of definite ALS.4

DiscussionThis association is infrequent, with only 28 cases reported in the literature,1,5 and represents 2% of patients in our series. Both processes feature an immune-mediated pathogenic mechanism.6,7 A decrease in CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs)8 has been described; levels of these cells are associated with ALS progression and altered nitric oxide synthesis.9 It is also reported that muscle and neuromuscular junction involvement may already be apparent in the initial stage of ALS.6,10,11

Mulder et al.12 describe a decrease in action potentials in patients with ALS, which varies according to muscle analysed.13 For example, Wang et al.14 observed a decrease > 10% in 43% of patients with ALS and in 70% of those with MG. This finding was associated with disease progression and predominantly affected proximal muscles (frequently the trapezius) in patients with ALS, whereas distal muscles showed greater involvement in MG.

When both entities coexist, MG symptoms are mainly ocular and bulbar. In these cases, immunomodulatory treatment should be considered as a diagnostic and therapeutic option.1 Furthermore, positive anti-AChR antibody titres have been reported in up to 5% of patients with ALS. Although the cause is unclear, this may be related to the early involvement of the neuromuscular junction, which may also explain the higher levels of anti–low-density lipoprotein receptor–related protein 4 (anti-LRP4) antibodies in this disease.1 Okuyama et al.15 detected higher titres during periods of more aggressive disease activity and lower titres in stages of clinical stability.

Therefore, we conclude that although the available evidence suggests that early treatment of symptoms of neuromuscular junction involvement improves survival in patients with ALS, diagnosis of ALS/MG overlap syndrome should only be considered when signs and symptoms of MND are observed in association with clinical signs of neuromuscular junction involvement (preferably ocular or bulbar signs) or positive titres of anti-AChR, anti-MuSK, or anti-LRP10 antibodies; and response to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors.1

Please cite this article as: Santos-Lasaosa S, López-Bravo A, Garcés-Redondo M, Atienza-Ayala S, Larrodé-Pellicer P. Esclerosis lateral amiotrófica y miastenia gravis (síndrome overlap): presentación de 3 nuevos casos. Neurología. 2020;35:595–597.