Ptosis is a frequent neurological sign that can be caused by lesions to numerous locations and associated with multiple aetiologies, with mechanical, aponeurotic, myogenic, neuromuscular junction–related, neurogenic, and central causes having been reported.

Only 4% of cases of ptosis are bilateral. Bilateral ptosis may be caused by lesions to frontoparietal or mesencephalic areas involving the oculomotor nerves.1

Midbrain stroke is rare, accounting for only 1% of all cases of stroke. Paramedian midbrain lesions involve the nucleus of the third cranial nerve, which may cause asymmetric bilateral ptosis.2 On account of the rareness of this entity, we report the case of a patient with cardiovascular risk factors who presented sudden-onset bilateral ptosis.

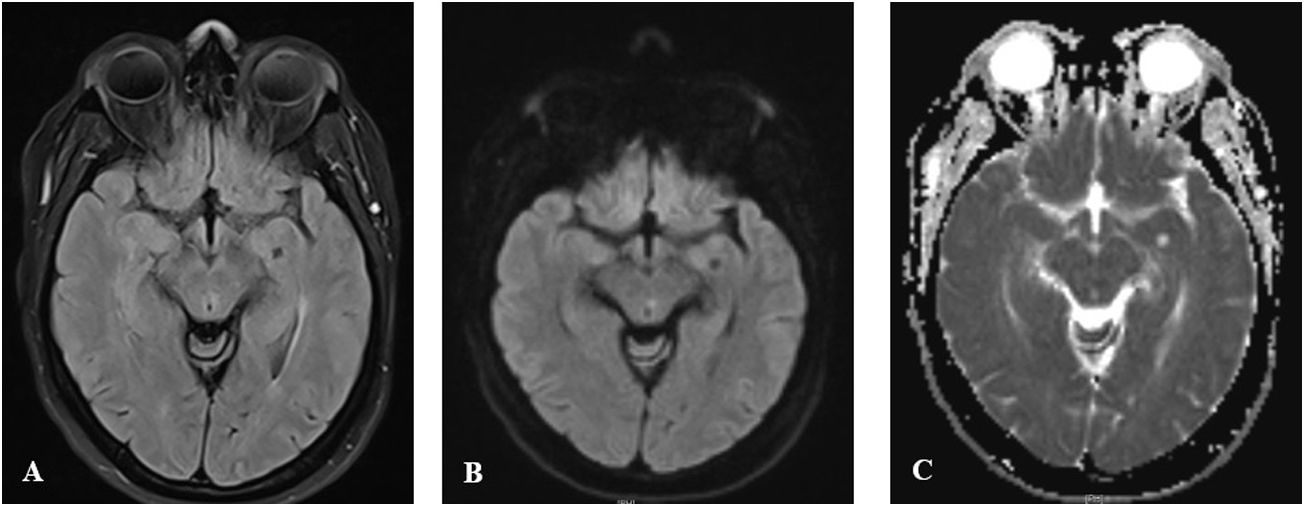

Clinical caseOur patient was a 45-year-old woman with history of poorly controlled arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus type 2, and dyslipidaemia who was referred to the emergency department due to sudden-onset ptosis following a hypertensive crisis. The physical examination revealed hypertension (191/100 mm Hg) and asymmetric bilateral ptosis. She displayed no pupillary changes, visual field alterations, ophthalmoparesis, or ocular muscle fatigability. A head CT scan detected a possible lesion to the left midbrain, and diffusion-weighted MRI confirmed diffusion restriction in the left paramedian region of the midbrain (Fig. 1). We ruled out an infectious, metabolic, or autoimmune aetiology; echocardiography revealed hypertensive heart disease. We therefore assumed that the episode was of vascular origin, establishing a diagnosis of left mesencephalic lacunar stroke. Ptosis resolved and blood pressure was controlled; the patient was discharged with a prescription for acetylsalicylic acid, and her antihypertensive treatment was adjusted.

DiscussionDespite the high clinical prevalence of ptosis, the correlation between lesion location and aetiology may be highly heterogeneous.

Bilateral ptosis usually presents in the context of myasthenia gravis. However, other entities should also be considered, including congenital ptosis, Horner syndrome, and mitochondrial diseases.1 Sudden onset frequently suggests an underlying vascular cause, especially in patients with cardiovascular risk factors.

The superior tarsal muscle, which is sympathetically innervated, and the levator palpebrae superioris muscle, innervated by the third cranial nerve, are responsible for upper-eyelid opening.3

The oculomotor nerve nuclear complex is located in the midbrain. The Edinger-Westphal nucleus, a parasympathetic nucleus located at the midline, is responsible for pupillary dilation. The central caudal nucleus, also located centrally within the oculomotor nerve nuclear complex, innervates the levator palpebrae superioris muscle, while 4 paired nuclei innervate the ipsilateral inferior rectus, medial rectus, and inferior oblique muscles, as well as the contralateral superior rectus muscle.4

This explains why unilateral midbrain lesions often cause bilateral ptosis (due to the bilateral innervation of the levator palpebrae superioris muscle by the central caudal nucleus) and bilateral paralysis of the superior rectus muscle (as the fibres that decussate from the nucleus innervating the contralateral superior rectus muscle pass close to the ipsilateral homologous nucleus). This explains why both nuclei are usually affected, resulting in bilateral weakness of the superior rectus muscle.5

Symptoms vary according to the exact topographical location of the lesion. Complete involvement of the extraocular muscles innervated by the third cranial nerve is frequent, sometimes in combination with hemiparesis, ataxia, or vertigo, due to damage to the pyramidal or cerebellar pathways.6

Our case demonstrates the wide range of possible diagnoses for ptosis. This is the third reported case of midbrain stroke presenting exclusively with bilateral ptosis,7 with preserved ipsilateral ocular motility and contralateral superior rectus muscle function. Our case is unique in that only the central caudal nucleus was damaged, while the remaining nuclei were preserved despite their topographical proximity.

However, despite the limited number of cases reported to date, we should always suspect vascular aetiology in the event of sudden-onset bilateral ptosis, and early neuroimaging studies should be performed.

FundingThis study received no funding of any kind.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author contributionsMaterial preparation and data collection were performed by Dr Pérez Navarro, Dr Sánchez-Miranda Román, Dr Martín Santana, and Dr Malo de Molina Zamora. The first version of the manuscript was drafted by Dr Pérez Navarro and Dr Sánchez-Miranda Román. All authors reviewed the manuscript draft and read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

We wish to thank the radiology department at Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular for the images.

Please cite this article as: Pérez-Navarro L, Sánchez-Miranda Román I, Martín Santana I, Malo de Molina Zamora R. Ptosis palpebral bilateral: ¿Cuándo sospechar causa vascular? Neurología. 2022;37:704–705.