PNKP gene mutations cause neurodevelopmental disorders with varying degrees of epilepsy, psychomotor retardation, cerebellar atrophy, and peripheral neuropathy1. Different phenotypes have been described in the literature:

- 1

Microcephaly, seizures, and developmental delay (MIM #613402). The condition, first described by Shen et al. in 2010, follows an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. Patients present congenital microcephaly, early-onset epilepsy rapidly progressing to developmental and epileptic encephalopathy, and intellectual disability.1–4

- 2

Ataxia-oculomotor apraxia 4 (MIM #616267). First described by Bras et al. in 2015, it is characterised by ataxia and oculomotor apraxia secondary to cerebellar atrophy. Patients frequently present axonal sensorimotor polyneuropathy, but do not present microcephaly or epilepsy.3,5,6

- 3

In recent years, cases have been reported of patients with intermediate phenotypes3,4,7–10:

Microcephaly with neurodegeneration and polyneuropathy. This phenotype is a combination of the 2 phenotypes previously mentioned. The syndrome is caused by presence of the p.Thr424Glyfs*48 frameshift variant in homozygosis, and was described by Poulton et al. in 2013, in 2 siblings with congenital microcephaly, epilepsy, ataxia, and progressive cerebellar degeneration.2,4,7

Charcot-Marie-Tooth–like disease. Characterised by pes cavus, sensorimotor polyneuropathy, and progressive ataxia. These patients do not present oculomotor apraxia, epilepsy, or intellectual disability.8,9

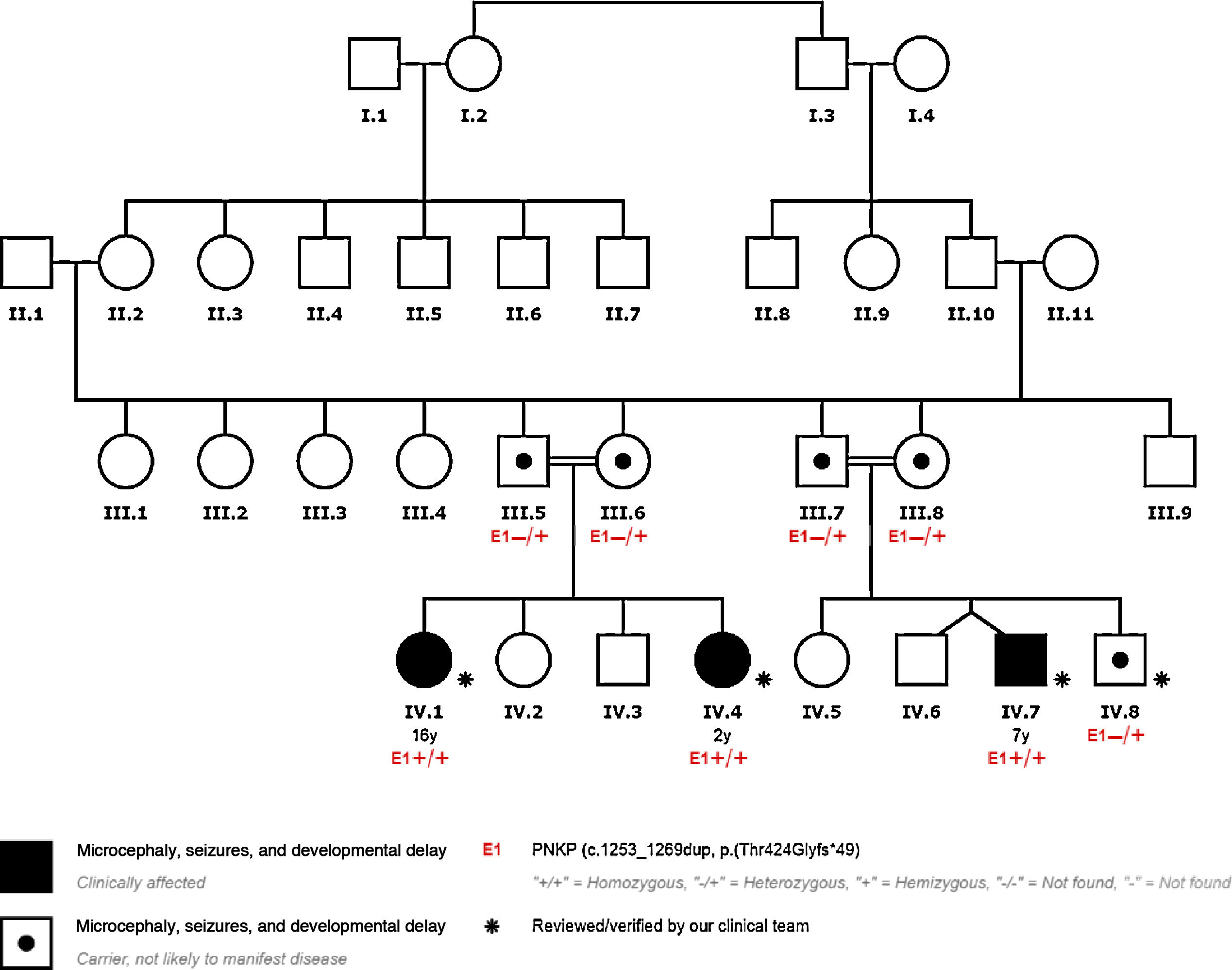

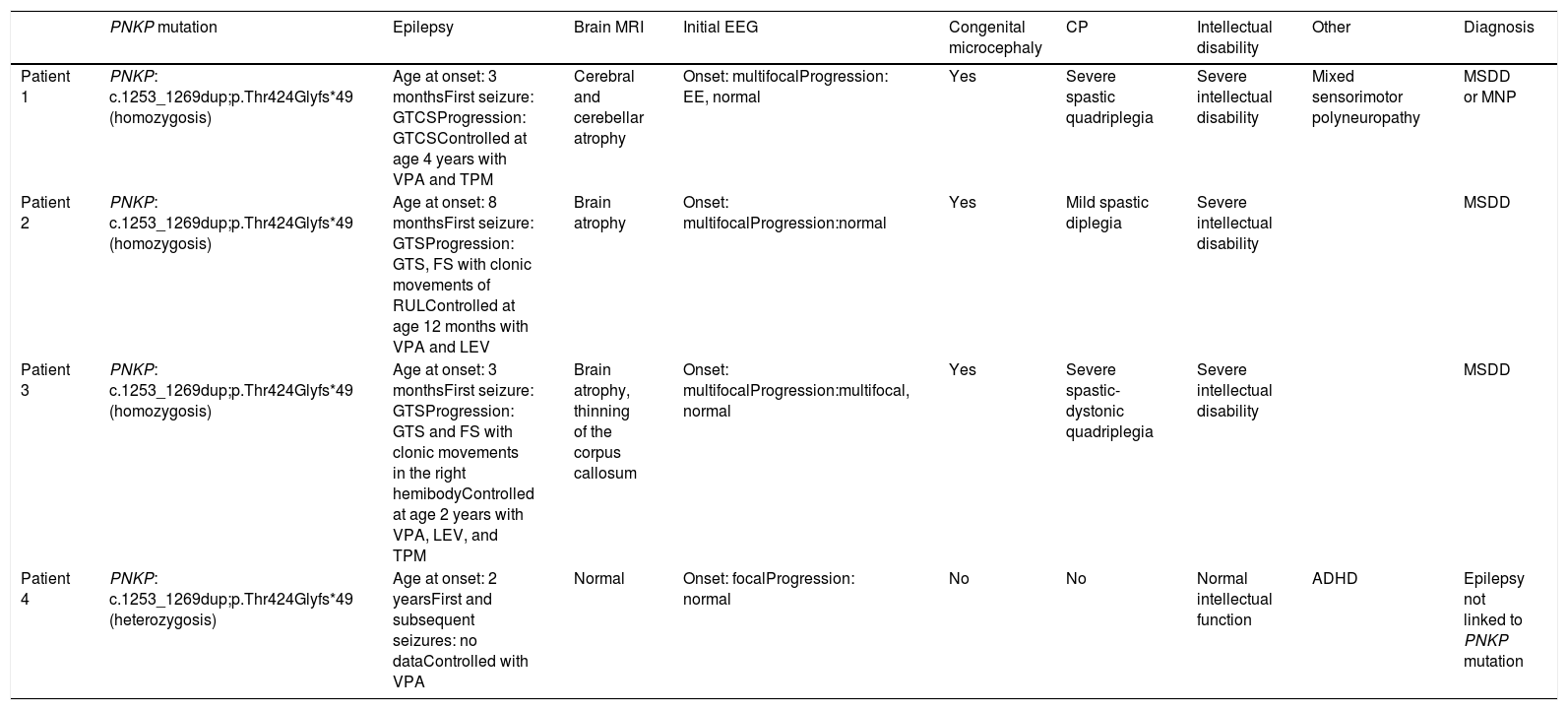

We present the cases of 4 patients from a single family with PNKP pathogenic variant NM_007254.3:c.1253_1269dup;p.Thr424Glyfs*49, detected by clinical exome sequencing. This variant has previously been described as pathogenic (Table 1, Fig. 1).

Characteristics of our patients.

| PNKP mutation | Epilepsy | Brain MRI | Initial EEG | Congenital microcephaly | CP | Intellectual disability | Other | Diagnosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | PNKP: c.1253_1269dup;p.Thr424Glyfs*49 (homozygosis) | Age at onset: 3 monthsFirst seizure: GTCSProgression: GTCSControlled at age 4 years with VPA and TPM | Cerebral and cerebellar atrophy | Onset: multifocalProgression: EE, normal | Yes | Severe spastic quadriplegia | Severe intellectual disability | Mixed sensorimotor polyneuropathy | MSDD or MNP |

| Patient 2 | PNKP: c.1253_1269dup;p.Thr424Glyfs*49 (homozygosis) | Age at onset: 8 monthsFirst seizure: GTSProgression: GTS, FS with clonic movements of RULControlled at age 12 months with VPA and LEV | Brain atrophy | Onset: multifocalProgression:normal | Yes | Mild spastic diplegia | Severe intellectual disability | MSDD | |

| Patient 3 | PNKP: c.1253_1269dup;p.Thr424Glyfs*49 (homozygosis) | Age at onset: 3 monthsFirst seizure: GTSProgression: GTS and FS with clonic movements in the right hemibodyControlled at age 2 years with VPA, LEV, and TPM | Brain atrophy, thinning of the corpus callosum | Onset: multifocalProgression:multifocal, normal | Yes | Severe spastic-dystonic quadriplegia | Severe intellectual disability | MSDD | |

| Patient 4 | PNKP: c.1253_1269dup;p.Thr424Glyfs*49 (heterozygosis) | Age at onset: 2 yearsFirst and subsequent seizures: no dataControlled with VPA | Normal | Onset: focalProgression: normal | No | No | Normal intellectual function | ADHD | Epilepsy not linked to PNKP mutation |

CP: cerebral palsy; EE: epileptic encephalopathy; EEG: electroencephalography; FS: focal seizure; GTCS: generalised tonic-clonic seizure; GTS: generalised tonic seizure; LEV: levetiracetam; MNP: microcephaly with neurodegeneration and polyneuropathy; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; MSDD: microcephaly, seizures, and developmental delay; RUL: right upper limb; TPM: topiramate; VPA: valproic acid.

Patient 1: 16-year-old girl who presented epilepsy at 3 months of age in the form of status epilepticus. Epilepsy was controlled at 4 years of age. She also presented congenital microcephaly, spastic quadriplegia, and intellectual disability. A brain MRI scan revealed cerebellar atrophy and diffuse thickening of the diploë. The patient presents calf atrophy and absent patellar and Achilles reflexes. The EMG study revealed predominantly axonal mixed sensorimotor neuropathy.

Patient 2: 2-year-old girl who presented epilepsy at 8 months of age, and status epilepticus at one year of age. She also presented congenital microcephaly, cerebral palsy, and severe intellectual disability. A brain MRI scan revealed diffuse cerebral atrophy.

Patient 3: 7-year-old boy, presenting epilepsy at 3 months of age, with several episodes of status epilepticus. Epilepsy was controlled at 2 years of age. He also presented microcephaly, cerebral palsy, and severe intellectual disability. A brain MRI scan revealed diffuse cerebral atrophy and thinning of the corpus callosum.

PNKP pathogenic variant c.1253_1269dup;p.Thr424Glyfs*49 was detected in homozygosis in patients 1, 2, and 3.

Patient 4: 8-year-old boy, who began to present frontal lobe seizures at the age of 2 years. He did not present microcephaly, intellectual disability, or cerebral palsy. Neuroimaging studies revealed normal results. He only presented attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder, with normal intellectual function.

We detected PNKP variant c.1253_1269dup;p.Thr424Glyfs*49 in heterozygosis; this patient was therefore considered to be an asymptomatic carrier of the mutation. His epilepsy is a phenocopy, meaning that while it presents similar phenotypic traits to those of patients with the homozygous mutation, these cannot be attributed to the mutation.

All the parents of our patients were heterozygous carriers of the mutation.

DiscussionThe patients carrying the mutation in homozygosis (patients 1, 2, and 3) present early-onset epilepsy, developmental and epileptic encephalopathy, congenital microcephaly, cerebral palsy, and brain atrophy. They may be classified as having microcephaly, seizures, and developmental delay (MIM #613402), although patient 1 also presented neuropathy, which suggests the phenotype microcephaly with neurodegeneration and polyneuropathy.

In patient 4, epilepsy is a phenocopy, as it cannot be attributed to PNKP variant c.1253_1269dup;p.Thr424Glyfs*49 in heterozygosis.

Furthermore, all our patients’ parents presented the mutation in heterozygosis, and were asymptomatic carriers.

Several clinical presentations of PNKP mutations have been reported, some of which include epilepsy.

The reason why a single PNKP mutation may cause different phenotypes is unknown; this phenomenon, known as variable expressivity, may involve other genetic, epigenetic, and/or environmental factors3.

The appearance of intermediate phenotypes in recent years suggests that all phenotypes lie on a spectrum of the same disease. Genetic studies should be performed in patients with complex genotypes.

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from any public, commercial, or non-profit organisation.

Please cite this article as: Furones García M, Ortiz Cabrera NV, Soto Insuga V, García Peñas JJ. Características de la epilepsia secundaria a alteraciones en el gen PNKP. Neurología. 2021;36:713–716.